Table of Contents

- Introduction

What Are Human Rights, and Why Do They Matter? - Morality and Moral Sense

The Roots of Right and Wrong in Human Nature - Moral Philosophy and Metaethics

How We Understand and Justify Moral Beliefs - Nature or Nurture? The Morality Debate

The Origins of Conscience in Biology and Culture - Social Skills and Moral Behavior

How We Learn to Live Together - Law and Morality – A Diverging History

When Justice and Legality Part Ways - Social Reform – Definition and Dynamics

Changing Law, Culture, and Conscience - A Brief History of Social Reform

Voices of Conscience and the Evolution of Justice - What Are Human Rights?

Defining the Moral Bedrock of Modern Civilization - From Custom to Codification – A Global Timeline

Landmarks in the Evolution of Human Rights - Human Rights in the Age of Intelligence

New Challenges, New Responsibilities, New Hope - Conclusion – A New Moral Horizon

Human Rights as the Compass of a Conscious Civilization

1. Introduction

What Are Human Rights, and Why Do They Matter?

From the earliest societies to today’s global civilization, humanity has grappled with a fundamental question: How should we treat one another? At the heart of this question lies the concept of human rights—the idea that all people, by virtue of their humanity, possess certain inalienable entitlements to life, freedom, dignity, and participation in society.

Human rights are not merely legal protections or political slogans. They are moral principles: claims about what is just, fair, and necessary for a flourishing life. They represent the ethical backbone of democratic societies and the moral conscience of our global community.

The modern language of human rights emerged in the 18th century and reached global recognition in the 20th with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). Yet the story of human rights stretches far deeper into history and far wider across cultures. From ancient codes of justice to revolutionary declarations, from grassroots reformers to modern legal frameworks, the pursuit of human dignity has driven human progress—and resistance to tyranny.

But human rights are also contested, violated, and evolving. In the 21st century, they face new challenges: authoritarian resurgence, economic inequality, ecological collapse, mass displacement, and the ethical dilemmas posed by artificial intelligence and biotechnology. To meet these challenges, we must understand the roots of rights in moral philosophy, their translation into law and reform, and their future as living, adaptive principles.

This article explores:

- The nature of morality, including moral sense, philosophy, and metaethics

- The evolution of law and the relationship between law and moral values

- The role of social skills and behavior in ethical life

- The history of social reform and the moral heroes who changed the world

- A chronological journey through the landmarks of human rights

- And finally, how Integrated Humanism and initiatives like Science Abbey can uphold and advance human rights in the Age of Intelligence

To safeguard human rights is not only to defend freedom or law—it is to defend humanity itself: our capacity for compassion, conscience, and cooperation.

2. Morality and Moral Sense

The Foundations of Ethical Awareness in Human Life

Before law codes were written, before philosophers debated justice, before declarations of rights were proclaimed, there was morality—an intuitive sense of right and wrong that guided human interactions. Morality lies at the core of what it means to be human. It governs how we treat one another, how we judge ourselves and others, and how we imagine the kind of world we want to live in.

A. What Is Morality?

Morality refers to the system of values, norms, and judgments that define what is considered right or wrong, good or bad, fair or unfair within a given context. It is both personal and social—shaped by culture, but grounded in deep psychological and neurological processes.

While definitions vary, most theories agree that morality involves:

- Normative guidance (what one ought to do)

- Moral judgment (distinguishing right from wrong)

- Moral motivation (the desire to do what is right)

- Accountability (recognition of responsibility and consequences)

B. The Moral Sense: Evolutionary and Developmental Roots

Human morality is not purely a product of education or culture. Research in evolutionary psychology and neuroscience suggests that humans possess a moral sense—a biologically grounded capacity for empathy, fairness, cooperation, and guilt.

Key findings include:

- Infants as young as six months show preference for helpful over harmful behavior (Hamlin et al., 2007).

- Mirror neurons may support empathy by allowing us to “feel” others’ experiences.

- Primate behavior reveals early forms of fairness, alliance, and compassion (Frans de Waal, 1996).

- Moral intuitions often emerge before formal reasoning, suggesting that ethics is not merely taught, but also felt.

Thus, morality may be seen as an evolved trait that enabled early human groups to cooperate, resolve conflict, and build trust—essential for survival in complex social environments.

C. Conscience and the Voice Within

The term conscience refers to the internal faculty that enables individuals to reflect on their actions and evaluate their moral correctness. It is often described as an inner voice or guide.

Conscience is shaped by both innate emotional mechanisms and cultural learning. It is influenced by:

- Empathy – our capacity to feel with others

- Guilt – emotional discomfort when we violate our moral code

- Shame – awareness of how others judge our behavior

- Pride – positive reinforcement for moral integrity

A healthy conscience motivates ethical behavior not through fear of punishment, but through moral integrity—the alignment between one’s actions and one’s values.

D. Morality Across Cultures

While moral feelings may be universal, their expression is culturally variable. Different societies emphasize different virtues and duties. For example:

- Honor cultures prize loyalty, family, and reputation

- Justice cultures emphasize equality and individual rights

- Duty-based cultures stress role responsibility and communal harmony

Anthropologists and moral psychologists argue that despite surface differences, most moral systems share core themes: harm/care, fairness, loyalty, authority, purity, and liberty (Jonathan Haidt, The Righteous Mind). The emphasis placed on each varies by culture and historical context.

E. The Role of Morality in Human Rights

Morality, in its most universal form, underlies the concept of human rights. The belief that all human beings deserve dignity, freedom, and protection from harm emerges not only from legal doctrine but from our shared moral experience as social beings.

Human rights are, in essence, codified moral claims. They institutionalize our moral intuitions, transforming compassion into policy, and empathy into law.

In understanding the origins and nature of morality, we lay the foundation for understanding human rights—not just as legal constructs, but as expressions of a deep and ancient ethical impulse that connects all people across time and culture.

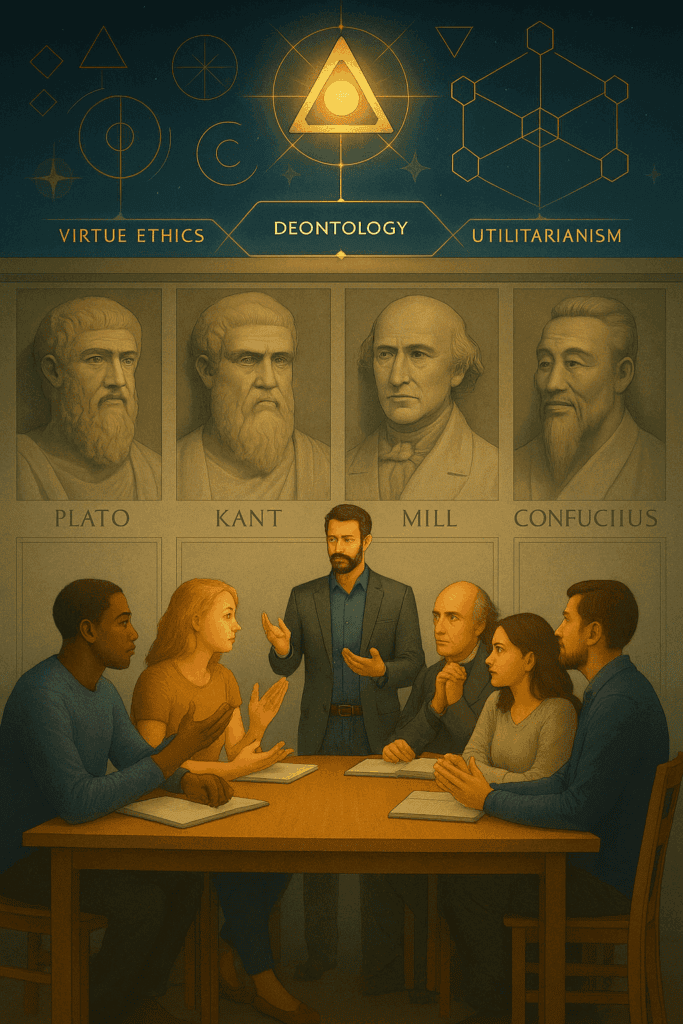

3. Moral Philosophy and Metaethics

The Quest to Understand Right and Wrong

While the moral sense may be instinctive, moral philosophy—also called ethics or moral science—is the deliberate, reasoned inquiry into what constitutes right action, good character, and a just society. From ancient sages to modern theorists, philosophers have sought to ground morality not only in custom or emotion, but in logic, principle, and the structure of reality itself.

A. What Is Moral Philosophy?

Moral philosophy is the branch of philosophy concerned with the systematic study of ethical concepts such as right and wrong, virtue and vice, duty and obligation, justice and rights. It asks:

- What ought we to do?

- What kind of person should I be?

- What is the good life?

The field is traditionally divided into three areas:

- Normative Ethics – Theories that prescribe how we should act.

- Applied Ethics – The practical application of ethical principles to real-world issues (e.g., bioethics, environmental ethics).

- Metaethics – The philosophical study of the nature, meaning, and origin of moral concepts.

B. Major Theories of Moral Philosophy

1. Virtue Ethics – The Ethics of Character

Originating with Aristotle, virtue ethics focuses on developing good character traits (virtues) such as courage, wisdom, generosity, and honesty.

- The goal is to live in accordance with reason and fulfill one’s human potential (eudaimonia or flourishing).

- Right action is what a virtuous person would do in a given situation.

Virtue ethics emphasizes moral development and context, rather than rules or consequences.

2. Deontology – The Ethics of Duty

Championed by Immanuel Kant, deontological ethics holds that certain actions are morally obligatory regardless of consequences.

- Morality is rooted in universal principles and rational duty.

- The categorical imperative commands us to act only on maxims we would will as universal laws.

This theory underlies many human rights formulations by insisting that people must be treated as ends in themselves, never merely as means.

3. Utilitarianism – The Ethics of Consequences

Developed by Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, utilitarianism judges actions by their outcomes.

- The right action is the one that produces the greatest happiness for the greatest number.

- Morality becomes a matter of cost-benefit analysis aimed at maximizing well-being.

Utilitarianism has influenced modern policymaking, public health, and economic ethics.

4. Contractarianism – The Ethics of Agreement

Emerging from Hobbes, Locke, and later John Rawls, contractarian theories see morality as a social contract:

- Individuals agree to moral rules for mutual benefit and protection.

- Rawls proposed a “veil of ignorance” to determine just principles that would be chosen by rational individuals unaware of their future position in society.

This theory emphasizes justice, fairness, and political legitimacy.

5. Ethics of Care – The Ethics of Relationship

A more recent development, care ethics (e.g., Carol Gilligan, Nel Noddings) critiques the abstract and masculine assumptions of earlier theories.

- It centers morality in human relationships, empathy, and responsibilities to others.

- Moral reasoning is contextual, narrative, and rooted in compassion and care.

This approach has reshaped moral discussions in education, medicine, and feminist thought.

C. Metaethics: What Is Morality, Really?

Metaethics explores foundational questions about morality itself:

- Are moral facts objective or subjective?

- Do moral truths exist independently of human belief?

- Are moral claims expressions of emotion, prescriptions, or statements of fact?

Some major metaethical positions include:

- Moral Realism – Moral truths exist independently of our beliefs (e.g., it is wrong to torture, universally).

- Moral Relativism – Moral truth is dependent on cultural or individual perspective.

- Constructivism – Moral truths are constructed by rational agents through practical reasoning.

- Emotivism – Moral statements express emotional attitudes, not factual claims.

- Error Theory – All moral claims are systematically false; they assume objective value where none exists.

Metaethics helps clarify whether human rights are discovered, created, or agreed upon—a critical issue in grounding their legitimacy across cultures and contexts.

D. Integrated Humanism and Moral Theory

From the perspective of Integrated Humanism, the great traditions of moral philosophy are not rivals but complementary lenses. Each offers insight into the nature of ethics:

- Virtue ethics fosters moral maturity.

- Deontology secures universal respect and rights.

- Utilitarianism ensures attention to outcomes and well-being.

- Contractarianism legitimizes moral governance.

- Care ethics humanizes the abstract with relational empathy.

Integrated Humanism affirms that morality is both rational and emotional, individual and collective, universal and contextual. It seeks a science of ethics that respects complexity while upholding a shared human dignity.

4. Nature or Nurture? The Morality Debate

Is Morality Born or Made?

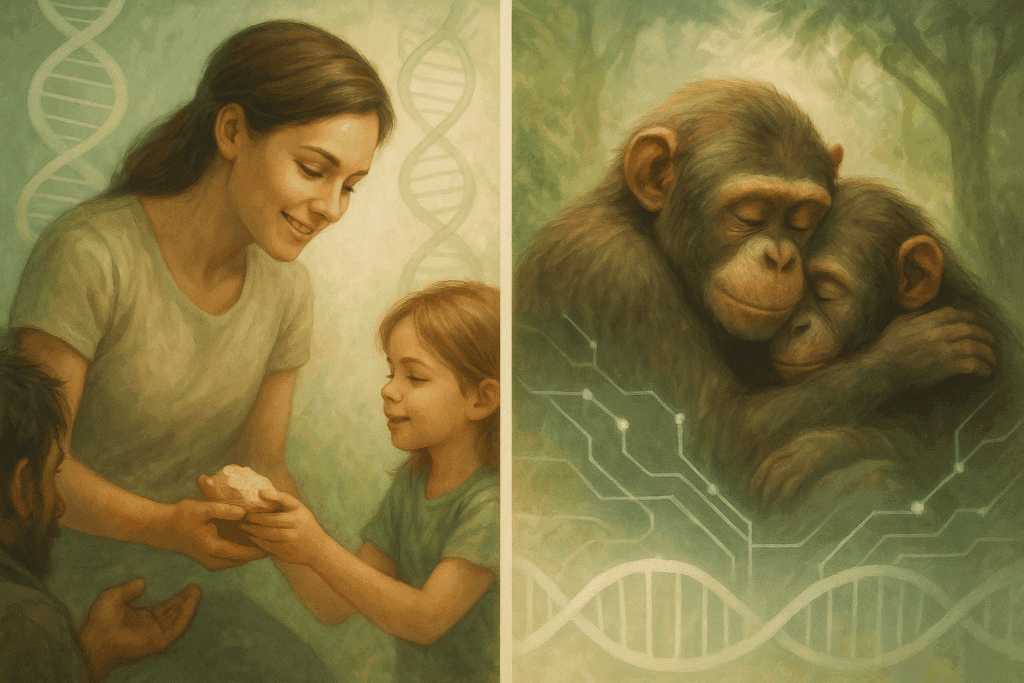

For centuries, philosophers and scientists have debated whether morality is an inherent part of human nature or a product of culture, education, and socialization. This debate—nature versus nurture—is not just academic; it shapes how we understand responsibility, reform, and the potential for ethical progress.

Today, research in neuroscience, psychology, anthropology, and evolutionary biology reveals that the answer is not either-or, but both: morality is neither entirely innate nor purely constructed. It is best understood as a dynamic interplay between biological predispositions and cultural development.

A. The Case for Nature: Innate Moral Capacities

Human beings appear to be born with certain moral intuitions and emotional capacities that support ethical behavior. These include:

- Empathy – the capacity to feel others’ emotions

- Fairness – sensitivity to equitable treatment

- Altruism – helping others without direct reward

- Guilt and shame – emotional responses that regulate social behavior

Scientific Evidence:

- Developmental psychology: Even infants show preference for prosocial behavior and distress at harm (Hamlin et al., 2007).

- Evolutionary biology: Traits like cooperation and empathy have adaptive value in group survival (de Waal, 2006).

- Neuroscience: The brain’s “moral network” involves areas like the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and anterior cingulate cortex. Damage to these areas can impair moral reasoning.

From this view, morality is an evolved feature of social mammals, especially humans, whose success depends on cohesive, cooperative groups.

B. The Case for Nurture: Morality as Cultural Learning

While we may be born with a moral potential, how that potential is shaped depends on culture, parenting, education, and environment. Different societies teach different values and expectations, often through:

- Rituals and storytelling

- Religious teachings

- Social norms and peer pressure

- Institutional reinforcement (schools, laws, media)

Anthropological Evidence:

- Moral values vary widely across cultures, especially in areas like sexuality, honor, obedience, and property.

- Practices considered moral in one society (e.g., polygamy, corporal punishment) may be condemned in another.

Social constructivists argue that morality is a cultural invention—a set of rules negotiated by communities to manage relationships, hierarchy, and power.

C. Modern Synthesis: An Interactive Model

The most accurate understanding today is an interactive model, where evolutionary predispositions are shaped and directed by social experience.

- Biology provides the capacity for moral emotion and cognition.

- Culture provides the content of moral belief and behavior.

This view supports the idea of universal moral principles (e.g., fairness, care, reciprocity) expressed in diverse moral systems. It also helps explain how moral change is possible—when social awareness or moral education reshapes cultural norms.

D. Implications for Human Rights

This debate has profound implications for the defense and promotion of human rights:

- If morality is innate, then human rights reflect something fundamental and shared across humanity.

- If morality is learned, then human rights require education, advocacy, and institutional support to take root and flourish.

From an Integrated Humanist perspective, this dual origin affirms both the potential for empathy and the need for deliberate moral cultivation. It suggests that building a just society involves both awakening conscience and designing systems that reinforce ethical behavior.

Morality is neither a fixed instinct nor an arbitrary invention—it is a human capacity that must be nourished, guided, and protected. In this way, the question of nature versus nurture becomes not a debate, but a mandate: to create the conditions where moral awareness can thrive.

5. Social Skills and Moral Behavior

The Interpersonal Foundations of Ethical Life

Morality is not only a matter of private conscience or philosophical reasoning—it is also a form of social intelligence. At its core, morality governs how we treat others, which means it is deeply intertwined with our social skills: the abilities that allow us to understand, cooperate with, and care for those around us.

To act ethically in society, one must not only know what is right, but possess the skills to relate to others with empathy, clarity, and mutual respect.

A. Defining Social Skills

Social skills are the learned abilities that allow individuals to interact effectively and harmoniously with others. These include:

- Communication – expressing thoughts and feelings clearly and respectfully

- Empathy – understanding and sharing the emotions of others

- Listening – giving others full attention and responding appropriately

- Cooperation – working together toward shared goals

- Conflict resolution – managing disagreements constructively

- Emotional regulation – managing one’s own emotions to behave appropriately in social contexts

These skills are essential not only for personal relationships, but for civic participation, workplace ethics, education, and justice.

B. Social Skills as Moral Capacities

The line between socially skillful and morally admirable behavior is often blurred. Consider how the following traits function both socially and ethically:

- Empathy underpins compassion and justice.

- Honesty is key to both trust and truthfulness.

- Cooperation is vital for fairness and group well-being.

- Respect affirms the dignity of others.

Social skills, then, are not merely tools for popularity or persuasion—they are moral instruments that shape the quality of our interactions and our moral impact on others.

C. Immoral Behavior as Social Breakdown

Conversely, immoral or antisocial behavior often reflects a failure of social skill or social integration. Examples include:

- Bullying and manipulation – using others for self-gain

- Deception – violating trust and truth

- Exclusion – denying others a place in the group

- Aggression – expressing emotion through harm or domination

- Disregard for consequences – failing to consider how actions affect others

Psychological research links deficits in social cognition (such as in certain personality disorders) with increased likelihood of exploitative or harmful behavior. This shows that moral development is not merely about knowing rules—it’s about developing interpersonal capacities.

D. Teaching and Cultivating Moral Behavior

Moral behavior can be learned and refined through the intentional teaching of social skills. Methods include:

- Modeling and mentorship – observing ethical role models in action

- Social-emotional learning (SEL) – formal education programs in empathy, regulation, and ethics

- Community engagement – learning through service, cooperation, and responsibility

- Restorative justice practices – emphasizing accountability, healing, and relationship repair

By emphasizing moral development as a social skillset, educators, parents, and institutions can foster environments in which ethical action becomes a natural extension of daily life.

E. Integrated Humanism: Ethical Society Through Skillful Living

Integrated Humanism sees ethical maturity not as the domain of a few, but as a potential in all. It affirms that moral behavior can be cultivated, just as language, reasoning, or creativity can.

From this view:

- Human rights depend on the social competence of individuals and institutions.

- Ethical communities are not built by rules alone, but by relationships grounded in trust, empathy, and mutual regard.

- The future of democracy, justice, and human dignity hinges on widespread ethical literacy—the everyday ability to act with others in mind.

Morality, in this light, is not a theory we memorize—it is a practice we embody, one interaction at a time.

6. Law and Morality – A Diverging History

When Legal Isn’t Always Right, and Right Isn’t Always Legal

Morality and law are often assumed to go hand in hand. Ideally, laws codify society’s shared ethical values, offering a framework for justice, peace, and protection. But history shows that morality and law can diverge sharply. What is legal may not be moral, and what is moral may not yet be protected—or even permitted—by law.

To understand the evolution of human rights, we must explore the relationship and tension between ethical principles and legal systems.

A. The Origins of Law

Law is one of the earliest institutions of organized human society. From oral tribal codes to written legal systems, law emerged as a way to regulate behavior, resolve disputes, and protect order. The oldest surviving legal texts include:

- The Code of Ur-Nammu (c. 2100 BCE – Mesopotamia)

- The Code of Hammurabi (c. 1754 BCE – Babylon), inscribed in stone, prescribing strict penalties based on status

- The Torah and its religious laws (Judaism)

- Dharmaśāstra texts (Hinduism)

- Confucian codes in East Asia, blending ritual, duty, and hierarchy

- Draco’s Code, implemented by Draco in Athens around the late 7th century BCE

- The Laws of the Twelve Tables (Latin: lex duodecim tabularum) were the foundational statutes of Roman law, officially issued in 449 BCE

- The Edicts of Ashoka of Emperor Ashoka of the Maurya Empire, who governed the majority of the Indian subcontinent in the third century BCE (Buddhism)

- The Corpus Juris Civilis (“Body of Civil Law”), or Code of Justinian, a compilation of key legal texts in Roman law, commissioned by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I and issued between 529 and 534 CE

Early laws were often religious, treating morality as divine command. Lawgivers were seen as prophets, kings, or philosophers with a mandate from gods or cosmic order.

B. Classical Legal Philosophy: The Moral Law

In classical philosophy, law was deeply connected to ethics. Thinkers like:

- Plato, who envisioned a just society governed by philosopher-kings guided by reason and virtue

- Cicero, who wrote of lex naturalis—a universal law rooted in reason and nature

- Confucius, who emphasized the moral duties of rulers and the harmony of social roles

Here, the ideal was that law should embody virtue, not merely enforce obedience.

C. The Enlightenment and Secular Law

The modern era brought a dramatic shift. The Enlightenment saw the rise of secular legal theory, where laws were grounded not in religion but in reason, consent, and contract. Key developments included:

- The rule of law: No one, not even the ruler, is above the law

- Separation of powers: Legislators, judges, and executives have distinct roles

- Legal positivism: The idea that law is defined by what is enacted, not what is moral

Thinkers like John Locke, Montesquieu, and later Hans Kelsen argued that law could be rational and neutral, even if morally imperfect.

But this also created a rift: legal ≠ moral. Laws could now exist without being ethically justified—so long as they were procedurally valid.

D. When Law Fails Morality: Historic Injustices

History is full of examples where legal systems upheld grave injustice:

- Slavery was once legal in most civilizations.

- Apartheid in South Africa was enforced by law.

- Genocide and ethnic cleansing, such as the Holocaust, were carried out under legal regimes.

- Criminalization of homosexuality, gender discrimination, and caste hierarchies have all been legitimized by law.

These cases expose the danger of treating law as automatically legitimate. They demand an external moral standard by which to evaluate and reform legal systems.

E. Natural Law vs. Legal Positivism

This leads to a central debate in jurisprudence:

- Natural Law theorists (e.g., Aquinas, Locke, Fuller) argue that unjust laws are not true laws at all. Law must be rooted in morality and reason.

- Legal Positivists (e.g., Bentham, Kelsen, Hart) maintain that law is defined by social facts and institutions, not moral content.

Human rights theory often walks the line between these views—acknowledging the authority of law, but insisting on its moral accountability.

F. Integrated Humanism: Reuniting Law and Ethics

From the Integrated Humanist perspective:

- Law is a tool, not a truth. Its legitimacy depends on its alignment with human dignity, equity, and reason.

- Ethical standards must guide legal reform, especially in rapidly changing fields like AI, biotechnology, and global migration.

- Science, ethics, and democracy must together shape a human-rights-based legal order—just, inclusive, and responsive to empirical reality.

Law is most powerful when it reflects moral insight and advances collective wellbeing, not when it simply reinforces the interests of the powerful.

Law and morality are not the same—but they must be in conversation. For when law is deaf to conscience, it becomes not protector, but oppressor.

7. Social Reform – Definition and Dynamics

Changing Law, Culture, and Conscience

Social reform is one of the most powerful expressions of humanity’s moral evolution. It represents our collective effort to correct injustice, expand freedom, and reshape societies to better reflect the ideals of equity, dignity, and shared well-being. Whereas revolutions often seek total upheaval, reforms aim to improve the system from within, guided by ethical reflection and civic engagement.

A. What Is Social Reform?

Social reform refers to the deliberate, organized effort to change laws, policies, institutions, or social norms in order to address injustice or improve conditions in society.

Key features of social reform:

- Moral motivation – driven by a sense of injustice or compassion

- Strategic action – involves advocacy, legislation, education, protest, or community organizing

- Incremental change – reforms often target specific problems rather than systemic overhaul

- Cultural as well as legal – reshaping minds and attitudes is as crucial as changing laws

Reform is not about charity or charity’s temporary relief—it is about structural transformation to prevent harm and expand rights.

B. Reform vs. Revolution

Though both aim at change, reform and revolution differ in method and philosophy:

| Reform | Revolution |

| Works within existing institutions | Seeks to overthrow or replace institutions |

| Gradual and legal | Rapid and often extra-legal or violent |

| Focuses on policy and law | Focuses on regime or power structure |

| Often moral and strategic | Can be ideological or emotional |

Many historical movements have included both reformist and revolutionary wings—e.g., the abolitionist movement, women’s suffrage, and civil rights.

C. Types of Social Reform

Social reform can address a wide range of human needs and rights:

- Legal reform – abolishing unjust laws or expanding legal protections

- Economic reform – improving working conditions, reducing inequality

- Political reform – expanding suffrage, combating corruption

- Educational reform – making education more accessible and inclusive

- Moral/cultural reform – changing public attitudes toward race, gender, disability, or environment

Reforms often begin as minority movements that are later embraced as mainstream ethics. History teaches us that many now-accepted rights—such as religious tolerance, civil equality, and labor protections—were once radical reforms.

D. Conditions for Successful Reform

Sociological and historical analysis shows that reform movements tend to succeed when they:

- Articulate a compelling moral vision

- Mobilize broad coalitions across sectors and identities

- Use a mix of tactics—legal, educational, protest-based, and institutional

- Engage existing power structures while challenging them

- Persist despite resistance, often across generations

Leadership matters, but so does community. Reform is not the product of a single voice, but of collective moral imagination and organized will.

E. Integrated Humanism and the Reform Ethic

From the perspective of Integrated Humanism:

- Social reform is the ethical engine of progress—the practical expression of evolving conscience

- Science, philosophy, and democracy must all work in concert to identify injustice and design intelligent remedies

- The reformer is not merely a critic, but a builder of a more just world

Reform is how ideals become institutions. It is the slow but unstoppable process by which what is moral becomes what is legal, and what is possible becomes what is real.

True reform is not cosmetic. It is moral architecture—a reworking of the foundations upon which societies stand.

8. A Brief History of Social Reform

Voices of Conscience and the Evolution of Justice

Throughout history, social reformers have been the architects of justice. They are the people who dared to challenge the status quo, confront prejudice, and transform the laws and customs that denied human dignity. Some were statesmen and scholars, others were teachers, spiritual leaders, or revolutionaries—but all shared a common trait: the moral courage to demand a better world.

This section highlights key reform movements and figures who redefined the moral boundaries of their societies, laying the groundwork for modern human rights.

A. Abolition of Slavery

The movement to end slavery is one of the earliest and most far-reaching examples of moral reform on a global scale.

- William Wilberforce (UK) campaigned for decades in Parliament, leading to the abolition of the British slave trade in 1807 and slavery in the empire in 1833.

- Frederick Douglass, a formerly enslaved American, became a powerful writer, orator, and statesman who exposed the moral contradictions of American democracy.

- Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, and Toussaint Louverture also led both peaceful resistance and revolutionary efforts to dismantle systems of bondage.

The abolitionist movement reframed slavery as not merely unfortunate, but morally intolerable—a crime against humanity.

B. Women’s Rights

The women’s rights movement sought equality in law, education, labor, and political representation.

- Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) laid an early philosophical foundation.

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony led the American suffrage movement, culminating in the 19th Amendment (1920).

- Emmeline Pankhurst and the British suffragettes used militant and nonviolent tactics to win the vote in the UK.

- Later reformers like Simone de Beauvoir and Gloria Steinem expanded the movement to challenge gender roles, discrimination, and violence.

Women’s rights reform has been essential to the recognition of gender as a human rights issue.

C. Civil Rights and Racial Justice

In the 20th century, civil rights reform reshaped democratic societies around the world.

- Mahatma Gandhi pioneered nonviolent civil disobedience in the struggle for Indian independence, inspiring global reform traditions.

- Martin Luther King Jr. led the American Civil Rights Movement, challenging segregation and advocating for racial equality through peaceful protest.

- Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress ended apartheid in South Africa after decades of imprisonment, resistance, and reconciliation.

These movements not only secured legal victories but redefined the moral language of race, citizenship, and equality.

D. Labor, Environment, and Disability Reform

Other major reform movements addressed structural inequalities and neglected populations:

- Labor reformers such as Karl Marx, Eugene V. Debs, and the trade union movement fought for workers’ rights, minimum wages, and humane working conditions.

- Environmental reformers, from Rachel Carson (Silent Spring) to Greta Thunberg, raised awareness of ecological justice and climate responsibility.

- Disability rights activists like Judith Heumann and the global disability justice movement led to landmark legislation like the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990).

Each of these reforms contributed to a broader redefinition of who deserves full dignity and inclusion in public life.

E. Reform Through Ideas, Art, and Science

Not all reformers led marches or held office. Many shaped public conscience through writing, teaching, and discovery:

- Charles Dickens and Victor Hugo humanized the poor in literature.

- John Stuart Mill, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Voltaire championed liberty and reason.

- Charles Darwin and Albert Einstein contributed to shifting worldviews that indirectly empowered reform by challenging dogma and promoting critical inquiry.

Ideas matter. Reform is often the long-term result of changing how people think, which then changes how they vote, govern, and relate to others.

F. Integrated Humanism and the Reform Tradition

Integrated Humanism honors this lineage of reform not merely as historical achievement, but as a living legacy.

From this perspective:

- Social reform is the practical application of moral philosophy.

- It connects compassion with structure, and justice with design.

- It is both individual and collective, driven by conscience and sustained by community.

In every generation, new injustices emerge—or old ones persist in new forms. Reform is the process by which moral clarity becomes political change.

The story of social reform is the story of humanity rising to meet its highest ideals. It reminds us that progress is possible—when enough people believe that what is, is not yet what ought to be.

9. What Are Human Rights?

Defining the Moral Bedrock of Modern Civilization

Human rights are the formal expression of humanity’s deepest moral commitments. They are the universal principles that declare: Every person matters. Every person deserves freedom. Every person is born with dignity.

But what exactly are human rights? How are they defined, defended, and understood? To build a just and intelligent society, we must be clear about the foundations of rights—and the values they express.

A. Definition of Human Rights

Human rights are the basic rights and freedoms that belong to every person, simply by virtue of being human. They are:

- Inherent – not granted by government, but born into every human life

- Inalienable – cannot be taken away, only violated or denied

- Universal – apply to all people, regardless of nationality, identity, or status

- Indivisible – civil, political, economic, and social rights are interconnected

- Impartial – not based on religion, race, gender, wealth, or ideology

They are grounded in moral philosophy, codified through law, and realized through political will and social movements.

B. The Moral Basis of Human Rights

Human rights are not simply legal constructs—they are moral claims rooted in core values such as:

- Human dignity – the intrinsic worth of every person

- Freedom and autonomy – the right to self-determination

- Equality – equal moral consideration and opportunity

- Justice – protection from harm and exploitation

- Solidarity – shared responsibility for the well-being of others

These values transcend culture and politics. While societies express them differently, the underlying moral intuition is widespread: no one should be subjected to cruelty, degradation, or systemic exclusion.

C. Categories of Human Rights

Human rights can be organized into several key domains:

- Civil and Political Rights

- Freedom of speech, religion, and conscience

- Right to vote, protest, and fair trial

- Protection from torture, arbitrary arrest, and discrimination

- Freedom of speech, religion, and conscience

- Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights

- Right to education, healthcare, housing, and decent work

- Right to participate in cultural life and access resources

- Protection from poverty and social exclusion

- Right to education, healthcare, housing, and decent work

- Collective and Environmental Rights

- Rights of indigenous peoples and minority groups

- Right to clean water, a stable climate, and sustainable development

- Rights of indigenous peoples and minority groups

Some critics argue that not all these rights are equally enforceable. But from an ethical standpoint, they are mutually reinforcing—you cannot live with dignity under political freedom while suffering material deprivation, and vice versa.

D. Human Rights vs. Civil Rights vs. Legal Rights

It’s important to distinguish between related but different terms:

- Human rights are universal moral principles that transcend national boundaries.

- Civil rights are legal protections granted by a particular state to its citizens.

- Legal rights are those recognized and enforceable under current law.

Example:

The right to education is a human right affirmed by international law. It may also be a civil right within a country’s constitution. But if it is not protected or implemented, it may be denied as a legal right in practice.

Human rights advocacy seeks to align all three—to make legal systems reflect universal moral truths.

E. Integrated Humanism and the Language of Rights

Integrated Humanism sees human rights not as political luxuries or Western inventions, but as rational moral imperatives:

- They are the ethical minimum for a society that claims to be just.

- They are essential for global cooperation, peace, and sustainability.

- They are both scientifically defensible (in terms of human needs and flourishing) and spiritually meaningful (in terms of human dignity and purpose).

Rights are not merely about individual claims—they are about shared responsibilities to one another and to future generations. They form the basis of a social contract rooted in reason, empathy, and justice.

To speak of human rights is to affirm the moral truth that every person matters. It is a commitment to build societies not just with power, but with principle.

10. From Custom to Codification – A Global Timeline

Landmarks in the Evolution of Human Rights

The path from ancient ethical customs to modern human rights declarations is neither linear nor confined to any single culture. Across centuries, diverse civilizations and reformers contributed to the idea that rulers must be accountable, the law must be just, and people possess inherent dignity.

This section presents a historical timeline of some of the most influential legal and moral milestones that shaped the modern concept of human rights.

A. Early Codes and Sacred Traditions

c. 2100 BCE – The Code of Ur-Nammu (Sumer)

The world’s oldest known legal code introduced the principle that even rulers must follow written laws and that punishments should be proportionate.

c. 1754 BCE – The Code of Hammurabi (Babylon)

Carved in stone, this code emphasized justice by punishment, introducing class-based distinctions and legal consequences.

Confucian Ethics (China, 500s BCE)

Emphasized moral duty, respect, and social harmony; not human rights per se, but a proto-ethical framework for civic dignity.

The Torah and Biblical Law (Middle East)

Contained early ethical mandates—such as care for the stranger, widow, and orphan—that laid the groundwork for moral universalism.

Dharmaśāstra (India, c. 200 BCE–400 CE)

Provided rules for ethical living and social duties based on class and life stage; foundational to Indian moral order.

B. Classical Thought and Natural Law

Socratic and Stoic Philosophy (Greece, 400s–100s BCE)

Taught that all humans share reason and dignity; the Stoics promoted the idea of a universal moral law above positive law.

Roman Law and Jus Gentium (Law of Nations)

Early Roman legal principles acknowledged a set of laws common to all human societies—a precursor to international law.

Cicero (106–43 BCE)

Asserted that just laws derive from nature and reason, and that unjust laws are not true laws.

C. Religious and Medieval Contributions

Islamic Sharia and the Constitution of Medina (7th century CE)

Introduced protections for religious minorities, rule of law, and social welfare principles.

Magna Carta (England, 1215)

A landmark in limiting monarchical power. For the first time, even the king was subject to law, and nobles gained legal protections—a seed for later rights-based constitutions.

The Edicts of Ashoka (India, 3rd century BCE)

Promoted compassion, religious tolerance, and moral governance based on Buddhist values.

Canon Law and Scholastic Philosophy (Medieval Europe)

Figures like Thomas Aquinas revived and integrated natural law theory, asserting that laws must serve moral ends.

D. Enlightenment and Revolution

The English Bill of Rights (1689)

Guaranteed rights to Parliament and laid the foundation for constitutional monarchy and civil liberties in Britain.

The Declaration of Independence (USA, 1776)

Affirmed the “unalienable rights” to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, based on natural rights theory.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (France, 1789)

One of the most important secular declarations of human rights, asserting liberty, equality, property, and resistance to oppression.

Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792)

Demanded that women be included in the rights discourse, challenging the male-centric Enlightenment canon.

E. 19th–20th Century Expansion

Abolition of Slavery (1833–1865+)

The British Slavery Abolition Act and the U.S. Emancipation Proclamation began a wave of global abolition and moral reckoning.

The Geneva Conventions (1864–1949)

Established international humanitarian law in times of war—prohibiting torture, mistreatment, and targeting civilians.

The League of Nations and Minority Treaties (1919)

Laid early groundwork for collective rights protection post-WWI.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR, 1948)

Drafted after the atrocities of WWII and the Holocaust, the UDHR is the foundational global human rights document. It affirms civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights for all people, regardless of nation, race, or creed.

F. Late 20th Century to Present

International Covenants (1966)

The ICCPR and ICESCR gave legal force to the UDHR’s principles.

Conventions on the Rights of Women (1979) and Children (1989)

Extended human rights protection to specific vulnerable populations.

International Criminal Court (2002)

Established jurisdiction over crimes against humanity, genocide, and war crimes.

Yogyakarta Principles (2006)

Affirmed human rights protections for LGBTQ+ individuals under international law.

G. The Continuing Struggle

Despite these achievements, human rights remain contested and unevenly enforced. Many parts of the world still face:

- Repression of dissent and political rights

- Systemic racism, casteism, and religious discrimination

- Gender-based violence and legal discrimination

- Ecological destruction without recourse

- Digital surveillance and threats to autonomy in the AI age

Progress continues—but so does the work of reform, accountability, and innovation.

H. Integrated Humanism and the Timeline Ahead

From the perspective of Integrated Humanism, this timeline is not just history—it is a curriculum in moral evolution. Each document, each reform, is a milestone in collective ethical awareness, and a step toward building a global society where reason, empathy, and dignity define our shared life.

The story is ongoing. And we are its current authors.

11. Human Rights in the Age of Intelligence

New Challenges, New Responsibilities, New Hope

As humanity enters the Age of Intelligence—defined by rapid advances in artificial intelligence, biotechnology, planetary data systems, and global interconnectivity—we face new ethical frontiers. While the core values of dignity, liberty, and justice endure, the tools and threats of this era demand a reinvigoration of human rights thinking.

This is a time not only of risk, but of extraordinary opportunity to reimagine human rights as dynamic, adaptive, and deeply integrated into the fabric of intelligent civilization.

A. Technological Acceleration and Ethical Gaps

Breakthroughs in AI, genomics, and digital infrastructure are transforming what it means to be human—but regulation and ethical understanding lag behind.

Key threats to rights in the Age of Intelligence include:

- Digital surveillance and the erosion of privacy

- Algorithmic bias in legal, financial, and medical systems

- Job displacement through automation, deepening inequality

- Data commodification—where human attention, emotion, and behavior become products

- Biopower—governments and corporations influencing or modifying bodies and minds through tech

These issues are not futuristic—they are current, and they affect millions already. Without a moral compass, intelligence alone can deepen injustice.

B. Expanding the Definition of Rights

In response, thinkers and activists are proposing new categories of human rights:

- Digital rights – including access to information, algorithmic transparency, and freedom from surveillance

- Cognitive liberty – the right to mental privacy, identity, and neurodiversity protection in the face of brain-computer interfaces and neurotech

- Environmental rights – protection from ecocide, the right to a habitable planet

- Rights of future generations – legal and moral consideration for those not yet born

The Age of Intelligence calls for rights that evolve with knowledge, not static dogma. Moral science must keep pace with technological progress.

C. The Role of Education and Cultural Transformation

Technology changes the landscape. But culture defines the direction.

To safeguard rights in this age, societies must:

- Foster ethical literacy in education—from kindergarten to professional AI development

- Strengthen global civic institutions with scientific grounding

- Promote cross-cultural dialogue on shared human values in an interconnected world

- Empower communities with tools for informed consent, digital citizenship, and collective agency

Intelligence must be embedded with empathy, not merely efficiency.

D. The Mission of Science Abbey and Integrated Humanism

Integrated Humanism is uniquely positioned to address this moment in history. It brings together the tools of science, the ethics of humanism, and the institutional imagination of democratic reform. In this vision:

- Human rights are understood scientifically—not as arbitrary entitlements, but as the conditions necessary for flourishing biological, social, and conscious life

- Human dignity is grounded in the shared experience of sentience, vulnerability, agency, and interdependence

- Justice is redesigned not through punishment, but through prevention, rehabilitation, equity, and mutual accountability

Science Abbey can contribute by:

- Advancing public ethics education in a non-dogmatic, accessible way

- Supporting policy proposals based on evidence, empathy, and democratic process

- Developing civic technologies to enhance transparency, participation, and inclusion

- Creating sanctuaries—digital, educational, and physical—for reflection, cooperation, and moral dialogue

Integrated Humanism offers a moral blueprint for a rational, compassionate civilization, one in which intelligence serves humanity—not the reverse.

E. Rights as Our Shared Moral Infrastructure

In the Age of Intelligence, human rights must become more than legal norms—they must become the ethical infrastructure of the global future:

- Rooted in evidence

- Guided by conscience

- Enforced through democratic systems

- Evolving with insight and innovation

The next stage of rights is not only what we protect, but what we collectively design—a society where freedom is balanced with responsibility, and technology is bound by compassion.

Human rights were once etched in stone. Now, they must be written into code, policy, architecture, and hearts. The Age of Intelligence demands nothing less than a new Enlightenment—a convergence of wisdom, science, and moral courage.

12. Conclusion – A New Moral Horizon

Human Rights as the Compass of a Conscious Civilization

Human rights are not just a legal framework. They are the moral scaffolding of civilization—our best attempt to translate empathy, reason, and fairness into structures that protect every person’s dignity.

From ancient codes written in clay and scripture to modern declarations forged in the aftermath of war, the story of human rights is one of increasing moral awareness. It is the unfolding realization that freedom must be protected, justice must be inclusive, and power must be accountable to conscience.

Yet history also teaches that rights are never permanent. They must be claimed, defended, reimagined, and extended with each generation.

A. The Ongoing Evolution of Conscience

Each era faces its own injustices—its own blind spots.

Today, we are challenged not only by inequality and oppression, but by new forces: artificial intelligence without ethical design, economic systems that prioritize data over dignity, and climate degradation that imperils the future of life itself.

In the Age of Intelligence, the defense of human rights must expand into the realm of intelligent systems, ecological stewardship, and intergenerational justice. Moral reasoning must keep pace with human power.

Integrated Humanism calls for a new moral horizon—one that embraces:

- Science without dogma

- Ethics without absolutism

- Rights without borders

- Democracy without manipulation

- Progress without exploitation

B. The Role of Science Abbey and the Humanist Mission

In this new era, institutions like Science Abbey can serve as civic sanctuaries—spaces where knowledge, reflection, and reform converge. Not temples of dogma, but forums of ethical inquiry and social transformation.

Science Abbey’s role is to:

- Educate—fostering moral literacy and civic awareness

- Convene—bringing together scientists, humanists, activists, and educators

- Design—creating tools, curricula, and technologies that support moral agency

- Inspire—cultivating global citizenship rooted in compassion and reason

By weaving together moral philosophy, social science, and democratic imagination, Science Abbey becomes a steward of human rights in the Age of Intelligence.

C. A Pledge for the Future

Let this article serve not as an end, but as a starting point for a shared commitment:

That every person deserves dignity—regardless of nation, status, identity, or circumstance.

That freedom and fairness are not luxuries, but lifelines.

That our future must be guided not only by what we can do, but by what we ought to do.

That human rights are not optional—they are the moral minimum for any civilization that claims to be just.

And that the work of conscience continues, in every law reformed, every mind awakened, and every life uplifted.

The history of human rights is still being written. And we are its next authors.

Let us write with wisdom. Let us write with courage. Let us write with compassion.

Let us rise toward a new moral horizon—together.