Magic and Science: Danger and Power

In the early days of science, thinkers did not separate science from spirituality. Until the nineteenth century, scientists maintained a holistic worldview that comprehended every aspect of experience and knowledge.

Copernicus revered Hermes Trismegistus, Tycho Brahe studied astrology, and Johann Kepler followed Pythagorean philosophy. Robert Boyle, Isaac Newton and Elias Ashmole were accomplished alchemists and early leaders of the scientific Royal Society. Ashmole was the second man on record to be made a Freemason.

All the more integral was the understanding of the medieval alchemist and Renaissance magician. Renaissance magic was a mixture of syncretism, sacred geometry, and the physical sciences, or more accurately, proto-science.

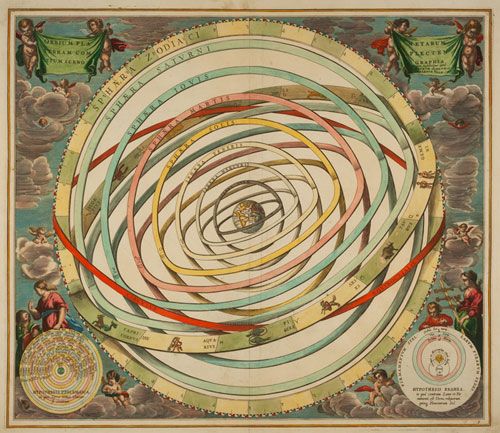

Syncretism is the comparison and drawing analogies between mythologies and religious or philosophical ideas in order to demonstrate an underlying unity. Sacred geometry refers to Pythagorean or Neoplatonic uses of mathematics to explain spiritual concepts. The cosmology of the magician often relied heavily on Christian Kabbalism and Hermeticism.

Alchemy in its various forms in the Middle Ages was both celebrated and stigmatized. Alchemy was both the mysterious science of the wise and the cunning deceit of the fraud. Certain branches and theories of math and science were acceptable in medieval and Renaissance Europe.

If it did not offend the local religious superstitions, and if it pleased the Crown, it was safe, especially for men of wealth and power, to practice scientific experimentation and propose theories. Some governments even patronized alchemists for various political and economic purposes.

A Tale of Two Henrys

King Henry IV of England was a usurper to the throne and constantly on the defense against assassination attempts and rebellion. Fearful that alchemists might fund his enemies or devalue his coin, Henry IV acted to ban alchemy altogether. Parliament passed the Act Against Multipliers in 1404, making the multiplication of silver or gold by means of alchemy a felony.[1]

Henry IV’s grandson, Henry VI, came out of several wars in need of money. In 1440 he issued a number of patents to practice alchemy, in contradiction of his grandfather’s statute.[2] The practice of alchemy continued and thrived in England and the Continent. Many books on the subject were published and there was significant patronage for the practice of alchemy.[3][4] Alchemists were sought by elites for use in the mining, chemical and medical industries.

German nobility, such as Julius, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, Henry V, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, Augustus, Elector of Saxony, and Julius Echter von Mespelbrunn, were especially inclined toward alchemy.[5] Even Rudolf II, the Holy Roman Emperor (1552-1612) in Prague, supported alchemists.

The German Wilhelm IV (1532 – 1592) and his son Moritz von Hessen-Kassel (1572 – 1632) were avid scholars, scientists and alchemists who surrounded themselves with the greatest minds of their time. They built the foremost laboratory in the world during their lifetimes.[6]

Alchemy’s Relationship with the Dark Ages: “It’s Complicated”

Some royals during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance had their own court alchemist or astrologer. Some magicians were given royal prerogative, such as Henry Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (1486 – 1535), one of the greatest magi in history. Agrippa was a proclaimed magus, involved in occult societies and employed by the German Emperor, Maximilian I.

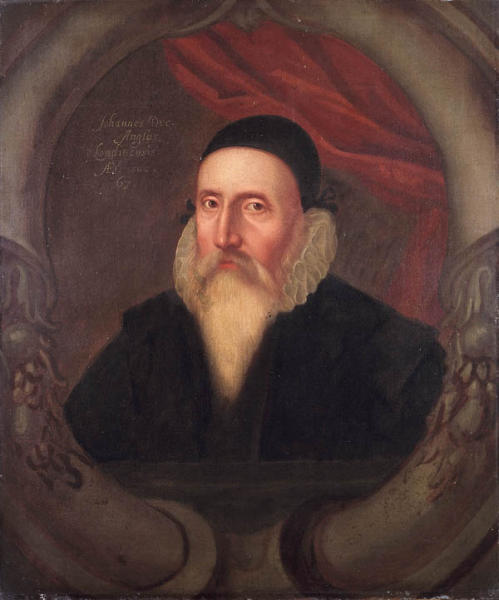

John Dee was admired by the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian as well as his own queen, Elizabeth I of England. His Enochian Magic is often considered by modern magicians to be one of the most powerful ever known.

During the age of exploration, Dee became the world’s foremost navigational mathematician and the prophet of the British Empire, for which he helped lay the foundation. As tutor and advisor John Dee was appointed Queen Elizabeth’s Royal Adviser on Mystic Secrets.[7]

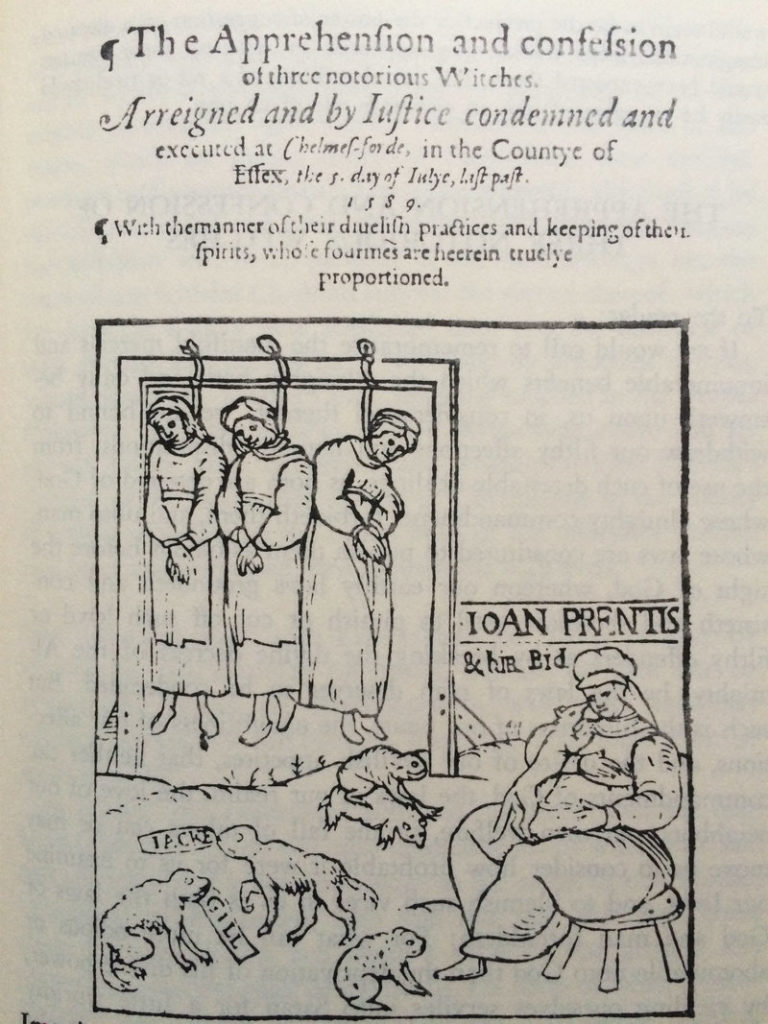

Yet, medieval magicians and alchemists like John Dee and Cornelius Agrippa were, despite rational argument, eventually tabooed by the propaganda of opponents of magic and science – even into the present day.

Anyone who studied mathematics, science or medicine in the Middle Ages was under threat of being called a magician or conjuror, and a heretic, and of course it was worse when his interests led him to studies of a mystical sort, which transcended organized religion.

Science in the Dark Ages could get you killed. All knowledge and government was based on faith. Many great minds of the human race have known what it is like to live in fear of one’s life because one does not believe in certain religious superstitions.

Anything that did not fall in line with the doctrine of the ruling Church patriarchs of the time was condemned as heretical or blasphemous, and punished with loss of property, liberty, limb and life.

Francis A. Yates, the groundbreaking researcher in the field of the Hermetic-Kabbalistic tradition, speculated that the failure of the early Masonic fraternity to boast John Dee among its main influences was a result of a successful smear campaign against Dee and this kind of fear of association.

In fact, only in the last half-century have professional academics begun to take seriously the proto-scientists and the mystical and syncretistic writings of respected scientific minds like Aristotle, John Dee, Elias Ashmole and Isaac Newton. Adapting to the social landscape, individuals or groups have been keen to conceal interests that do not conform to the current fashions of Church and State.

The Medieval Hermetic-Kabbalistic Tradition

The alchemist of the Middle Ages was usually a professed Christian, often a monk or clergyman, who studied what he could of Hermetic alchemy, Greek philosophy, the Jewish Kabbalah, and his own native and foreign magic. The Great Work of the alchemist, in emulation of the “Great Architect,” was to unite the divine opposites, macrocosm and microcosm, to produce a unified and balanced whole. This practice is known in the Western Mystery Tradition as the mystical ascent.

After the Turks took the Byzantine Empire in 1453, Greek Orthodox Christian refugees fled to Italy, forcing the Greeks and Italians to learn to coexist together as a larger community. With the Greeks came manuscripts of Plato, Aristotle and the Christian Gospels. Italian humanists began to study Neoplatonism and Hermeticism and were able to find cultural common ground in some basic shared ideas.

The Hermetic-Kabbalistic tradition may be defined as the juxtaposition of Alexandrian Neoplatonism and Hebrew mysticism. The cosmopolitan environment cultivated by the Arabic golden age helped produce medieval Hermeticism and Kabbalah. These mystical traditions would be spread throughout Europe when the Jewish people were forcibly expelled from Roman Catholic Spain in 1492.

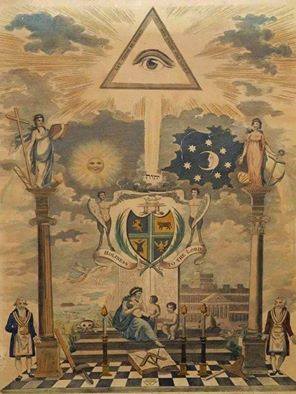

By the early seventeenth century the medieval Hermetic-Kabbalistic tradition had become an ever-evolving global cosmopolitan institution with the early Freemasons. In Britain Sir Robert Moray and Elias Ashmole were involved with the Hermetic-Kabbalistic tradition in Northern England and were both made Freemasons in the 1640s. The renowned Freemason William Preston’s (1742-1818) Lectures include the teachings of the Kabbalah.

In 1813 The United Grand Lodge of England was created out of the Premier Grand Lodge, with HRH the Duke of Sussex as Grand Master, and the Antient Grand Lodge, with HRH the Duke of Kent (his brother) as Grand Master. The Duke of Sussex became the first Grand Master of the new Grand Lodge. In his library were a number of essential Kabbalistic books.

Eliphas Levi (1810-1875), the famed magician and Freemason, wrote Elements of the Kabbalah; Albert Mackey’s An Encyclopedia of Freemasonry (1873) included the topic of Kabbalah; and Albert Pike admired the Kabbalah in his Morals and Dogma (1871). Arthur Edward Waite (1857-1942), Freemason and member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, was a prolific writer on esoteric subjects, including Kabbalah.

The famous Masonic author and English Literature teacher at the University of Iowa, Joseph Fort Newton (1880-1950), associated Kabbalah with the Craft. My own Masonic mentor William Kirk MacNulty (1932-2020), who was named Friar No. 94 in the Society of Blue Friars in 2005 for his contributions to Masonic literature, was an enthusiastic and sincere teacher of Kabbalah as well as Freemasonry. The Light of this gentlemen’s tradition burns strong even today.

Read more about Kabbalah and Freemasonry:

W. Kirk MacNulty

The Masonic Sourcebook

Masonicworld

Christian Kabbalism:

Ficino, Mirandola and Reuchlin

Christian Kabbalism began to flourish in the fifteenth century, when Cosimo de’ Medici offered his patronage to the Platonic academy in Florence centered on Marsilio Ficino (1433 – 1499 CE).

Ficino was a Catholic priest, a humanist, profoundly influenced by alchemical and magical texts. and the first to translate into Latin the complete works of Plato. He was also the translator of the Hymns of Orpheus, the Hymns of Zoroaster, the Corpus Hermeticum, and a number of the early Neoplatonic philosophers.

Ficino modeled his Florentine Academy on Plato’s Academy and became a major influence on Renaissance philosophy. One member of Ficino’s circle was Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463 – 1494 CE), who had Kabbalistic literature translated for him by a Jewish convert, and published his syncretistic 900 Thesis that grew to fame.

Pico was the first to assert that Kabbalah and magic were the best means to prove the divinity of Jesus Christ.[8] One notable immediate heir to Pico’s Kabbalistic interests was the German Johannes Reuchlin (1455 – 1522 CE), a notable humanist, Kabbalist and translator of Hebrew and Greek.

Midrashic authors had proclaimed the sacred nature of the twenty-two Hebrew letters in Talmudic times, and rabbis saw mystical meanings in the shapes of the letters. Every word and phrase of the Hebrew language was subject to mystical interpretation through Gematria, the practice of assigning spiritual meaning to numbers, and numbers to the letters of the alphabet, then interpreting the spiritual meaning of a word by the numerical value of its letters.

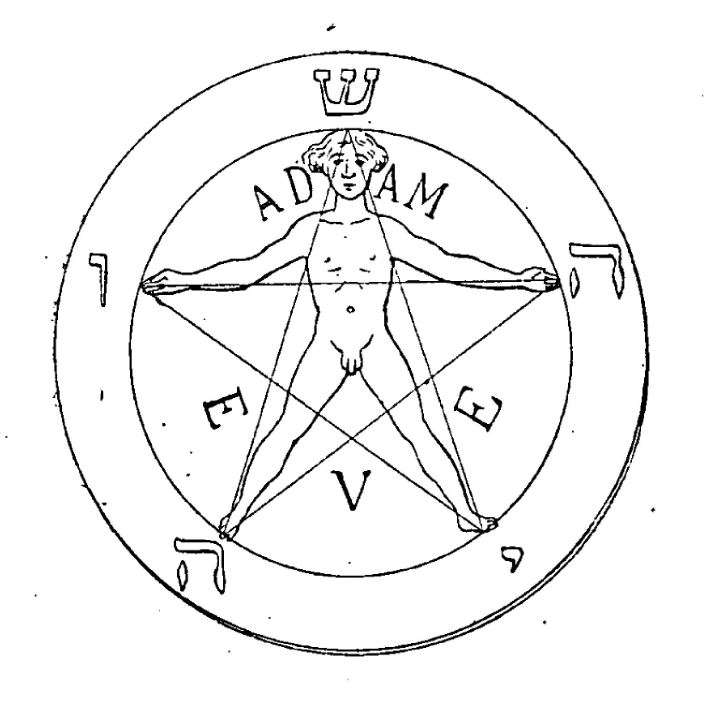

Following the example of Johannes Reuchlin, Christian Kabbalists would make much of the Pentagrammaton, an attempt to produce the Hebrew name of Jesus Christ. It consisted of the four letters of the Biblical name of God, the Tetragrammaton (yod-he-waw-he יהוה), with the letter shin ש in the center.

The four letters, yod, he, waw, and he, were taken to mean the four elements of Classical philosophy, hot, cold, wet and dry, or fire, air, water, and earth, which corresponded to the four worlds of the Mystical Ascent. Shin was taken to represent the spirit of Creation and life that animates the physical elements, or the perfected microcosm of man within the macrocosmic universe.

Jesus Christ was the path of redemption, and the Pentagrammaton thus symbolized the ultimate religious goal of the Christian Kabbalist, the mystical union of the opposites God and man, the complete embodiment of the divine. Christian alchemists express this devotion and mystical communion in their art, music, literature, science, labors and in the day-to-day, moment-to-moment realization of their own lives.

The Legendary Johann Faust

The German Dr. Johann Georg Faust (c. 1480 – c. 1540), known in English as John Faustus, was an alchemist and magician who rose to legendary status during the Renaissance.

Faust became the main character of a popular story developed around forty years after the man’s death. In 1587 Johann Spies printed The Historia von D. Johann Fausten, which was translated into English and subsequently inspired a playwright by the name of Chirstopher Marlow.

The story of the Faust character went viral in 1604 with Christopher Marlowe’s play The Tragicall History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus. Marlow’s play portrayed Faust as the quintessential Renaissance alchemist, but as the century came to a close, Faust had devolved in popular plays to a comical character of ridicule.

In the eighteenth century Spies’ biography was updated by G. R. Widmann and Nikolaus Pfitzer and published as Faustbuch des Christlich Meynenden. This version of the Faust story was read by a young Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749 – 1832). So In 1808 the legend was revamped yet again with Goethe’s play Faust.

The protagonist of Faust, a learned alchemist, transcends earthly knowledge and signs a pact with the devil (Mephistopheles). He thus sells his immortal soul for the secrets of Creation, power and the experience of the ultimate pleasure.

The character Faust was drawn as a reflection of Goethe, himself. Goethe, it may be noted, was a Freemason (Rite of Strict Observance, initiated by Amalia Lodge at Weimar on the eve of the Feast of St. John the Baptist in 1780) and a member of the original 1776 Order of the Illuminati.

The psychologist Carl Gustav Jung (1875 – 1961), whose grandfather Karl Gustav Jung was Grandmaster of the Masonic Grand Lodge in Switzerland, modeled his own form of alchemical magic, Analytical Psychology, on the great Goethe’s Faustian paradigm.

Johannes Trithemius:

The Humanist Magus Abbot

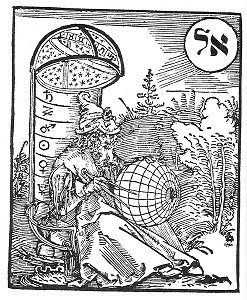

The German Johann Heidenberg, later known as Johannes Trithemius (1462 – 1516 CE), was a monastic humanist. He was abbot at the Benedictine abbey of Sponheim, where he greatly improved the library. Later, he became abbot of St. James’s Abbey in Würzburg, where he was buried. He was a scholar of Hebrew, Greek and Latin, a historian, a cryptographer and a reputed magician.

Trithemius authored the Steganographia, or Secret Writing, and the Annales Hirsaugiensis, or The Annals of Hirsau, the history of the important Hirsau Abbey, one of the first ever humanist histories.

Trithemius has been an inspiration to alchemists and those who practice magic. Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa (1486 – 1535) and Paracelsus (1493 – 1541) both studied under Trithemius and Thomas Vaughan (1621 – 1666) followed in the Trithemius tradition. The Trithemius cipher in his Polygraphiae was used to encrypt the Cipher Manuscripts, the founding documents of the principal nineteenth century magical society, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.

Paracelsus: The Alchemist

The Swiss physician Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim (1493 – 1541), better known as Paracelsus, saw in operative alchemy a theory of medicine rather than a quest for wealth. He posited that minerals, as well as vegetables or plants, could be used to treat disease.

Paracelsus’ quest was not for gold, but for the elixir of life, and he travelled through Europe, Africa and the Middle East searching after- and supposedly finding- that secret knowledge.

The quest for a compound that turned base metal to gold began to fall exclusively into the purview of frauds. It was abandoned by most serious alchemists as mineral and medical science, and advances in astronomy and human anatomy, evolved into the Scientific Revolution.

Paracelsus embodied the new alchemist, uninterested in the transmutation of metals, but passionate about health and the use of minerals as well as plants in the preparation of medicines.

Paracelsus accepted the conventional Greek cosmology of the four elements. The physical health of the body depended on the harmony of man or microcosm and nature or macrocosm. There was a kind of sacred geometry to his world-view, where balanced proportions of the three pure substances of life, itself, could be discovered and controlled thru the science of operative alchemy.

Like past alchemists, Paracelsus sought, and claimed to have found, the Philosopher’s Stone used in the elixir of life.

He introduced salt to the traditional alchemical duality of mercury and sulfur, to become the first to define the three symbolic cosmic substances, the tria prima: mercury, sulfur, and salt. Smoke described the volatility (the mercurial principle), the heat-giving flames described flammability (sulphur), and the remnant ash described solidity (salt).

Mercury (Spirit) was the feminine, moist and cold, and life-force; Sulfur (Father) symbolized the masculine, dry and hot, and the mind; and Salt (Son), a crystal, was a reference to matter and the purified physical body. Physicians seeking the cause and treatment of any disorder could refer to this model for guidance.

This three part formula became central to the Western alchemical world-view. Anyone familiar with Indian Ayurvedic medicine will recognize it in the three energies or gunas, rajas (activity), sattva (subtle essence), and tamas (gross matter and inertia); and Chinese scholars are also familiar with this scheme in qi (life-force), shen (spirit) and jing (essence).

Cornelius Agrippa: The Magus

Henry Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (1486 – 1535) was born in Cologne in the late fifteenth century. He was a philosopher, Kabbalist, alchemist, mystic, and indisputably the foremost magician of his time.

Agrippa understood magic in an expanded sense of its original meaning, as it alluded to the dualistic philosophy of the disciples of the prophet Zoroaster, the Persian magi. Out of the ranks of the magi were the three wise men of Christian folklore who followed the North Star to Bethlehem to be the first to recognize and worship the infant Jesus as the Christ.

In his Three Books of Occult Philosophy or Magic, Agrippa defended Magic as a Christian source of wisdom, denying any connection to sorcery or superstition. Magic was a comprehensive education, the “most perfect and chief science,” akin to Classical metaphysics or Christian theology. It was natural philosophy, or science.

Agrippa was widely read and open to wisdom from wherever it might come, discussing the opinions of great men, from Moses, Zoroaster, and Homer, to Aristotle, Pliny, Virgil, and Cicero, to Saint Paul and Saint Augustine, to Hermes Trismegistus and Roger Bacon. Agrippa stated on his first page that the intent of his Three Books was to delineate the structure of the mystical ascent (which is, as we have seen, the basic architecture underlying the various branches of the Western Mystery Tradition).

Agrippa’s popular hierarchy proceeded through God, ideas, angels and souls, spirits (mediums that transfuse virtues from the divine to the material), and material bodies.[5] Agrippa introduced alchemy into the Hermetic-Kabbalistic tradition, utilizing the astrological symbolism of the seven planets in his alchemical method, which John Dee would later adapt to his own system of magic.

John Dee:

The Mystical, Magical Scientist

John Dee (1527 – 1609) was a magician and alchemist with a reputation to match Agrippa’s, plus a talent for navigational mathematics. In fact, he was considered England’s foremost navigational mathematician in an age of unprecedented sea exploration. Predicting and encouraging exploration and empire, Dee was the prophet of the British Empire, which he helped found in many ways, and he was appointed Queen Elizabeth’s Royal Adviser on Mystic Secrets.[10]

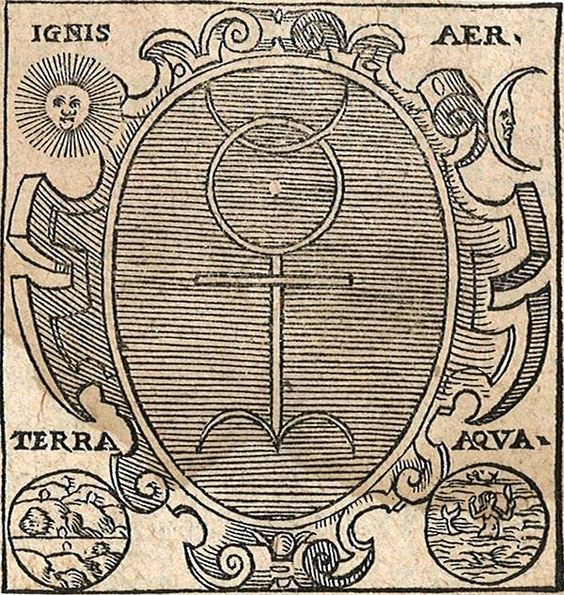

Dee conceived of mathematics as underlying all forms and forces of nature. Mathematics is the divine wisdom that lies between the supernatural unity of God and nature. The human mind mediates between the realm of ideas and the realm of the senses.

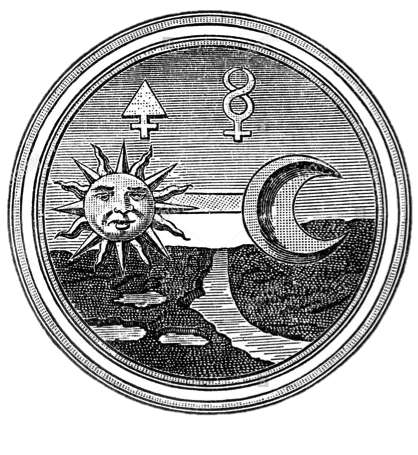

The human, represented by Mercury and the cross, lives within the five elements. The divine is symbolized by the point within the circle and the sun, or Sol in Latin. The world of the senses corresponded with the moon, Luna, the crescent line.

Dee’s mathematics was based on Euclid, Aristotle and Neoplatonism, and would be superseded by concepts developed by Descartes, Galileo and Newton, which formulated purely mechanical views of the universe. To later scientists mathematics was far separated from spiritual matters, but to Dee and other early alchemists, mathematics was deeply interwoven in the fabric of an organized holistic worldview.

Like Agrippa, Dee understood magic to mean the ability to tap into the force that animates the physical universe, in other words, holistic natural science. Dee created a system of angelic magic with his seer, Edward Kelley, that many later magicians would call the most perfect ever designed.

More importantly, Dee was familiar with Pico, Reuchlin, and Agrippa, and he propounded the Hermetic-Kabbalistic tradition in his famous preface to the 1570 translation of Euclid, widely read as the only translation of Euclid available in English at the time. His personal philosophy was best captured in his treatise called The Hieroglyphic Monad.

The Alchemical Monas Meditation

The Monas was a geometrical figure that combined the various elements of the alchemical symbols of the seven metals or planets, to represent the unity of the universe.[11] In the charge of the Second Degree in William Preston’s authoritive Illustrations of Masonry, 1775, one reads that Geometry is the basis of the Masonic art, which pertains to the divine and moral nature. This fundamental and prominent Masonic principle is distinctly reminiscent of the philosophy of John Dee.

This same figure found its way into the central place of Masonic symbolism, as well, on the First Degree Tracing Board and often, on the side of the altar, itself. Considering that the two parallel lines encasing the figure of the point within the circle suggest the two Saint’s John Days, which fall on the Summer and Winter Solstices, it would be difficult to argue that the figure of the point within the circle used in Masonic ritual did not, as in the alchemical and magical tradition, represent the sun.

All Freemasons are familiar with the primacy of the symbol of the sun in lodge form and ritual. The imagery of the sun and the moon in the alchemical tradition espoused by John Dee is found on the Masonic First Degree Trestleboard.

Finally, the figure of the point within the circle appears in Western esoteric tradition, as the central image, holding the “supreme dignity,” corresponding with the sun. In Dee’s Monas this symbol is placed in the center of the hieroglyphic universe.

With the historical persistence and prominence of the seven alchemical metals or planets in the Western esoteric tradition, it is possible to conjecture an early association of them with the seven members of the perfect Masonic lodge, the seven lodge officers.

Further, Frances A.Yates argues that the esoteric tradition of the Elizabethan Age in England that influenced Edmund Spenser, Albrecht Dürer, and William Shakespeare centered on John Dee, and it was from The Hieroglyphic Monad that the German Rosicrucian philosophy emerged.[12]

Rosicrucianism

The Rosicrucian Movement, based on a system of Christian alchemical mysticism, embodied many aspects of the Renaissance Hermetic-Kabbalistic tradition. The order began as a myth in the early seventeenth century, originally published in Germany in two anonymous manifestos, the Fama Fraternitatis Rosae Crucis and Confessio Fraternitatis.

Written mid-seventeenth century, the manifestos specifically indicate that their mythical founder, Christian Rosenkrutz, studied “Magia and Cabala” (Fama Fraternitatis) and praise is given to Paracelsus, the famous sixteenth century alchemist.

The Rose Croix symbol is associated with the legend of Christian Rosenkreuz, the father of the Rosicrucian Order. The Rosy Cross is a symbol of the Great Work, the means and end of the alchemist, the union of opposites in the “chemical” marriage of microcosm and macrocosm. It is the golden elixir or Philosopher’s Stone that turns all into gold.

The Rosicrucian philosophy and Art was based on medicine and healing, mathematics and mechanics, but the main goal of its Art was spiritual. The society, itself, was fictional, but many believed the manifestos’ claims of authenticity.

Learned alchemists appreciated the concept of the Invisible College developed in these manifestos and several Hermetic fraternities were formed in the heart of Christendom. The Art of Hermes is the theory and practice of speculative alchemy, producing wholesome elixir or medicine, in the alchemist’s allegorical laboratory.

Gentlemen like Robert Fludd (1574 – 1637) the renowned English alchemist, published works of support in order to be received into the Rosicrucian fraternity. Fludd defended good magic against bad, associating good magic with mathematics and natural philosophy.

Francis Bacon (1561 – 1626) was the philosophical antecessor of the future British Royal Society. That elite scientific community included alchemist Freemasons in its ranks like Elias Ashmole, a founder, and Isaac Newton, President 1703 – 1727.

Bacon did not approve of the alchemical tradition of hiding truth in symbolism. Bacon’s main concern was universal enlightenment, while the Rosicrucian manifestos, for example, blanket their mystical teachings in alchemical symbolism and obscure allegory.

Like Francis Bacon, however, the Rosicrucian manifestos promoted advancement in learning, and they suggested the existence of a secret society that closely resembled the one introduced in Bacon’s fictional New Atlantis.

Francis Yates suggests that both were concerned with the ecumenical magico-scientific advance, which, grounded in the liberal arts, reached to the heights of the mystical union by way of the mystical ascent.[13]

Legacy of the Rosy Cross

Certain individuals are known to have had connections with both the Rosicrucian and the early Masonic communities, most prominently the alchemist Elias Ashmole, the second recorded Speculative Freemason in history. As early as 1638 Freemasonry was associated with the “brethren of the Rosie Crosse,” in a poem published in Edinburgh.

Evidence exists for a joint meeting between the two fraternities, and a century later the Rose Cross grade was created for the Masonic degree system. The early Freemasons therefore certainly had access to the Rosicrucian mystical philosophy, which has been shown to be adaptable to Masonic purposes, when they formed their own deity-centered, liberal arts-oriented secret society.

The brethren of the Rosy Cross and the brethren of Freemasonry were fiercely religious and antagonistic to the spread of atheism and secular government. In 1783 the Order of the Golden and Rosy Cross, the chief Rosicrucian society in the eighteenth century, officially declared war against the original Bavarian Order of Illuminati (Illuminatenordes formed 1776). They accused the Illuminati of atheism and undermining the Christian religion.

The Illuminati were also suspected of transmuting Freemasonry into a political system. It was feared that the Illuminati were plotting a secular Pan-European constitution, such as the European Union, today. It may be said that the battles against the Illuminati succeeded in those days to dismantle the order and drive it underground somewhat, but the Illuminati won the war. The unraveling of history seems to be in favor of the goals of the Bavarian order.

Today the Rose Croix is a symbol closely associated with high grade Freemasonry, Rosicrucian orders, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, Ordo Templi Orientis alchemical ritual and Crowlian (Thelemic) Magick. Those who are most interested in the Rosy Cross are the same people who are interested in the Bavarian Illuminati.

Fraternal organizations such as the Freemasons have nowhere near the influence they possessed before the Second World War. I can offer from my own experience in the Washington D.C. area and London, however, that members in the United States, Europe and elsewhere do include those operating in the highest ranks of academia, finance, government and the military. The legacy of the Hermetic-Kabbalistic tradition is thriving with plenty of momentum going into the future.

Cheers!

SOURCES

[1] Carolyn Gramling, “Benchmarks: January 13, 1404: England prohibits Alchemy,”

Earthmagazine.org, 26 Oct., 2015,

https://www.earthmagazine.org/article/benchmarks-january-13-1404-england-prohibits-alchemy/

[2] Geoghegan, D. “A Licence of Henry VI to Practise Alchemy.” Debus, Allen G. Ed.

Alchemy and Early Modern Chemistry:

Papers from Abix. The Society for the History of Alchemy and Chemistry. 2004.

[3] Lauren Kassell, “Secrets Revealed: Alchemical Books in Early Modern England,” Hist. Sci., xlix, 2011,

https://www.hps.cam.ac.uk/files/kassell-secrets-revealed.pdf

[4] James Stuart Campbell, “The Alchemical Patronage of Sir William Cecil, Lord Burghley,”

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/41336603.pdf

[5] Tara E. Nummedal, Alchemy and authority in the Holy Roman Empire, p.85-98

[6] The Landgrave Karl of Hesse-Kassel (1744 – 1836), whose mother was the Princess Mary of England,

was initiated into the Bavarian Order of the Illuminati in February 1783.

His daughter Marie Sophie married Frederick VI, the future king of Denmark.

[7] Woolley, Benjamin. The Queen’s Conjurer. New York: Henry Holt and Company. 2001.

[8] Farmer, S.A. (trans.) Syncretism in the West: Pico’s 900 Thesis (1486). Tempe, Arizona:

Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies. 1998.

[9] Agrippa, Henry Cornelius. Three Books of Occult Philosophy or Magic. London: 1651.

Fascimile, Kessinger Publishing.

[10] Woolley, Benjamin. The Queen’s Conjurer. New York: Henry Holt and Company. 2001.

[11] Dee, John. The Hieroglyphic Monad. London: 1564.

[12] Yates, Frances A. The Rosicrucian Enlightenment. London and New York: Routledge. 2004.

[13] Yates, Frances A. The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age. London: ARK Paperbacks. 1983.

Learn about Alchemy in Freemasonry and Rosicrucianism