Ancient Indian Alchemy

The Vedas: Ancient Indian Philosophy, Yoga, Alchemy & Magic

Ancient Indian alchemy began with the Vedas, developed with yoga and blossomed into Tantra. India has been a land of diverse ideologies, but the first and principal manuscripts on Indian religion, the Vedas, have had an effect on every one.

The Indian Vedic hymns were written in the 16th century BCE but are speculated to be based on ideas prominent 2,500 BCE. The Vedic period lasted from then until about 600 BCE, marking the settlement of the polytheist Aryans from the Caucasus Mountains of central Asia and their integration with the natives of India.

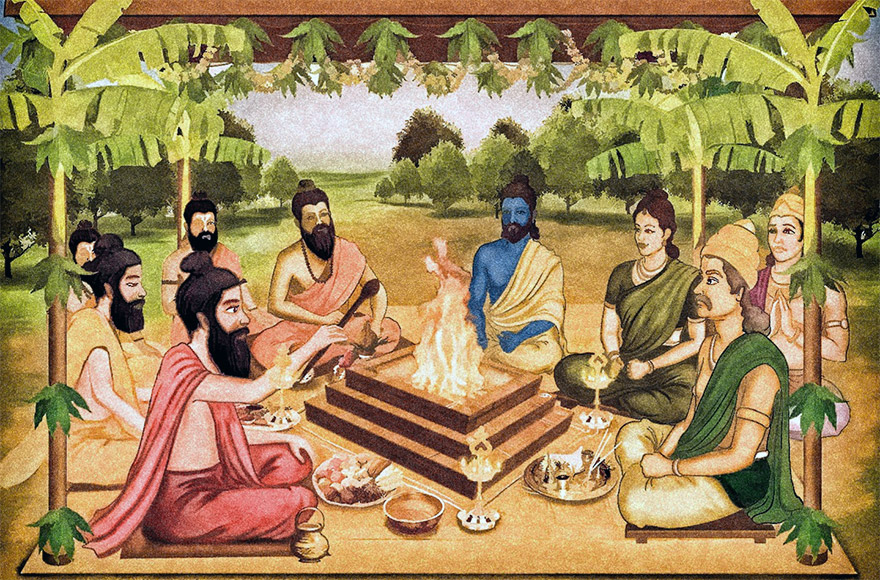

The Vedas were the literature of the poets, priests and philosophers. According to tradition, the compiler of the Vedas was the dark-complected sage Vyasa, a figure introduced in the Mahabharata and still revered to this day. With some Caucasian influence, the Vedas had much in common with Mediterranean, Celtic and Nordic cultures.

The interest of Indian philosophy in this early period evolved historically in a natural progression from the complexity of polytheism, to the simplistic duality of monotheism, and then in the Upanishads on to the cosmic, unknowable oneness of monism.

Ancient Vedic hymns to the gods declare that in the beginning existence arose from nonexistence. They describe an unborn, primeval One that existed before heaven and earth and produced all things. All gods, in fact, are but titles given the One by the sages. This One is Lord of all things, the unknown god that established eternal law. Truth, law and justice were represented in many forms, including the god Soma, a sacred hallucinogenic elixir of immortality drank by the gods and in Vedic ritual.

The Hymn to Purusha, the Cosmic Man, describes the immortal god of life, whose body was part in heaven and was part the living creatures of the earth. In language resembling alchemical symbolism, it is written that:

The moon was born from his spirit,

from his eye was born the sun,

from his mouth Indra (thunderstorm) and Agni (fire),

from his breath Vayu (wind) was born.[1]

The ancient Vedic magicians healed through spells and incantations against evil spirits and evil magicians, as evidenced in the earliest Vedas. Brahmin priests were the physicians until the Muslim conquest of India, about the turn of the first millennium. The Brahmins were adept surgeons and pharmacists, but while their spiritual anatomy was quite extensive, physical anatomy was lacking.

[1] Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and Charles A. Moore, A Sourcebook in Indian Philosophy,

Princeton University Press, 1989, p. 20.

Early Indian Alchemy

There are four Vedas, each of which contains hymns, ritual and sacrificial duties, and philosophical writings. The Vedas introduced the practice of magic. Also, they set the foundation of the social order that was to persist to the twenty-first century, which encourages the aged householder to retire to the forest, and the forest-dweller to practice meditation.

The oldest Veda is the Rig Veda, ancient hymns about the gods, around which the later Vedas are based, written as early as 1,500 BCE. The Yajurveda focused on ritual, the Samaveda expressed scripture as chants, and the Atharvaveda is a collection of hymns teaching magic, religion and medicine for daily life.

The Atharvaveda, written around the eighth century BCE, contains the first mention of gold with the magical power of longevity, in the form of a talisman. In the next century the Satapatha Brahmana describes gold as “fire, light and immortality.”[1] The fourth century BCE Arthasastra mentions the metal Mercury, which would later become the focus of Indian alchemy, known as Rasasastra (Rasha sastra), the “Science of Mercury.”

These first overtly alchemical texts in India began with the legendary second-third century CE Buddhist alchemist monk Nagarjuna, a patriarch of Chan (Zen) Buddhism and the founder of Vajrayana. He is alleged to have used an elixir based on liquid mercury “rasa,” mixed with vegetable and mineral fluids, to transmute base metals into gold. The Rasa sastra described processes of preparing compounds of herbs with metals, especially mercury, minerals and other materials. These were used as medical remedies and tinctures for longevity, becoming part of the Ayurvedic regimen.

The First Meditators: Indian Yoga

[1] Allen G. Debus, Editor, Alchemy and Early Modern Chemistry:

Papers from Ambix, Sheppard, H. J., ‘Alchemy, Origin or Origins?’

Jeremy Mills Publishing for The Society for the History of Alchemy and Chemistry,

2004, pp. 32-33.

Rasa & Kanada:

The Science of Mercury and Atomic Theory

At the dawn of the first millennium the Shaivite Raseśvara tradition developed a list of processes upon mercury intended to ultimately make the physical body immortal. Revering mercury as sacred, the only path to moksha, or spiritual liberation, adherents would consume it or apply it as oil to the flesh. Unfortunately, it was not until the twentieth century that the sometimes fatally toxic properties of mercury were fully understood.

In contrast to this superstition was the first awakening of scientific thinking. The Indian philosopher Kanada lived between the sixth century and second century BCE. His philosophy resembled that of the fifth century BCE Greek Natural Philosopher Democritus.

Democritus theorized the cosmos as empty space filled with pure atoms such as air, water, soil and metals; which could become atomic mixtures like mud and wood. He is known as the “Father of Modern Science” in the sense that he was the first to advance a rational, materialist, mechanistic atomic theory of the universe. However, like Kanada, he based his theory on philosophical musings rather than empirical evidence.

Kanada was an atheist and believed that the human being could use logic to understand the universe through the mental process of subdividing the universe into its smallest parts, what he called the anu (atom), which is indivisible and eternal. The self, ‘Atman,’ could attain moksha, or liberation, via this contemplation. Kanada wrote the Vaisheshika sutras and founded the Vaisheshika school of atomic naturalism.

From the seventh century operative and speculative alchemy developed together with hatha yoga and the magical ritual of tantric yoga. Procedures were meant to separate spirit from matter and produce gold, or immortality, from base materials. The operations performed on the physical elements were analogous to the processes within the spiritual body of the alchemist. After the eighth century, the medical term Rasayana, lengthening the lifespan, was often applied to alchemy.

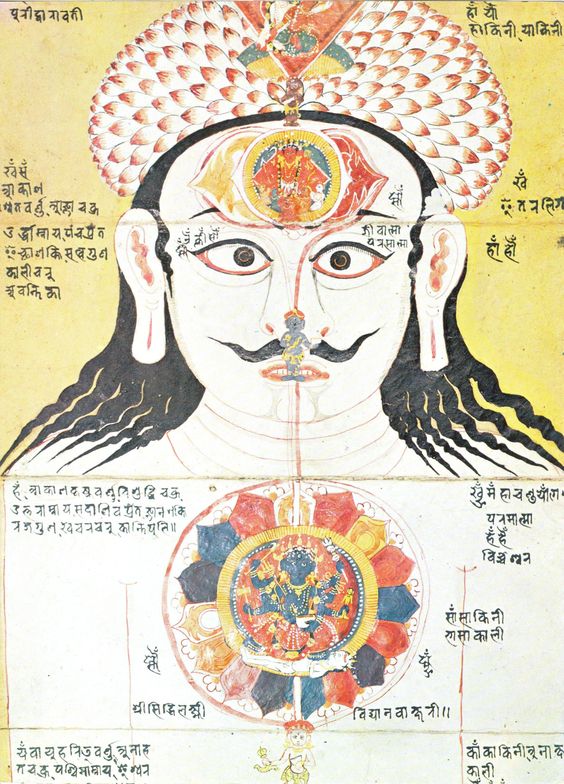

The tenth century yogi saint Matsyendranātha is said to have been the founder of hatha yoga, the Kaula tantric school and the Nath lineage of Shaivism. It is from this tradition that the main body of Rasayana literature emerges. Kaula tantra began as Shakti worship and progressed with hatha yoga to include meditations on Kundalini rising up the chakras. The Nath lineage is centered around the Siddha, the ‘wise man’ or ‘perfected one,’ and is divided into monks and householders.

Buddhist Internal Alchemy: Vajrayana

Vajrayana means diamond or thunderbolt tradition, in reference to the vajra, a weapon of myth used for ritual purposes. Vajrayana was the practice of medieval wandering yogis in North India, who were influenced by Shaivism and Buddhism. These ascetics rejected the styles of Buddhism practiced in the monasteries and developed their own practices and occasional gatherings. Vajrayana is focused upon symbolism, ritual and magic (like extra-sensory perception). It is also known as Mantrayana for its use of mantra, or chant.

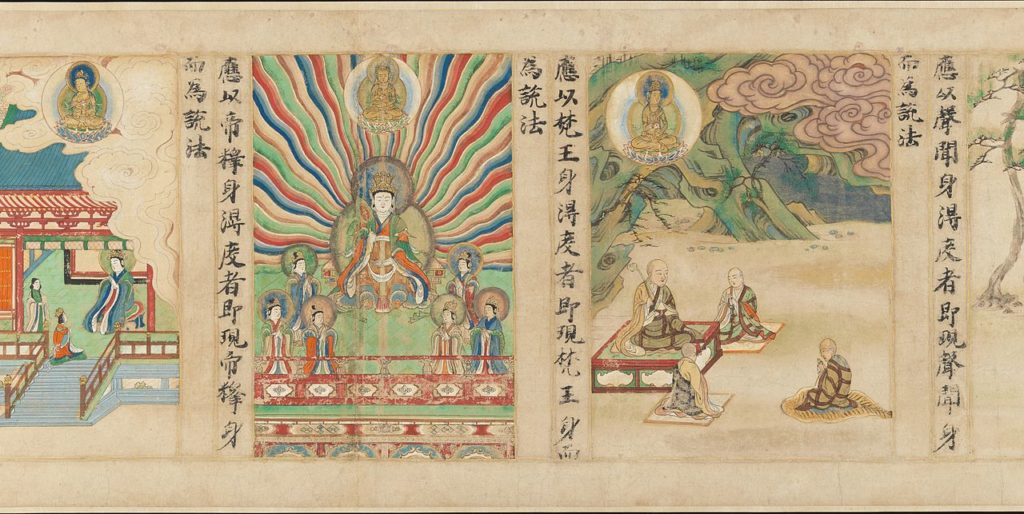

The origin of Vajrayana is related to the life of the legendary Indian alchemist Nagarjuna (second – third century CE), the first teacher of void or emptiness, legendary author of the Diamond Sutra and the fourteenth patriarch of Chan Buddhism. The Diamond Sutra, or Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra (The Diamond That Cuts Through Illusions) in Sanskrit, printed in 868 CE, is the oldest known printed book in the world.[1] It was the inspiration of Hui Neng, one of the early founders of Chan or Zen Buddhism.

The doctrine of the void interprets “voidness” as a state of mind and being. The void is wisdom or “prajna,” insofar as the meditator understands that all subjective experience is empty of objective reality. The absolute, or eternal, is unknown and unknowable.

[1] Jason Daley, “Five Things to Know About the Diamond Sutra,

the World’s Oldest Dated Printed Book,” Smithsonian.com, 11 May, 2016

Vajrayana Alchemy

Vajrayana is a form of inner alchemy. Nagarjuna is said to have transformed base objects into gold at his monastery, an allegory of the inner alchemist’s transformation of base existence into enlightenment using the methods of Vajrayana. Tantric techniques fall under the categories of yoga (psycho-physical exercises), mantra (chant), yantra (magical diagrams), mandala (cosmological art), mudra (physical gestures) and maithuna (sexual cultivation.) The goal of these practices is the cultivation of transcendent wisdom, sometimes personified as the goddess Prajnaparamita.

The Vajrayana is passed directly from guru to initiated disciple and often recorded in secret manuals called tantras. Tantra means ‘thread’ as in the thread of wisdom transferred in the teachings. Just as the sutras are the canonical literature of the Mahayana tradition, the tantra comprise the canon of Vajrayana, otherwise known as Tantric or Esoteric Buddhism. These traditions are said to have been taught by Buddha, himself.

The primary tantras are the esoteric Guhyasamaja Tantra (The Tantra of the Secret Community), the eighth – tenth century Hevajra Tantra (Hevajra is one of the eight tantric enlightened beings invoked by the yogi), and the Kalachakra Tantra (The Tantra of the Wheel of Time). Learn more about tantric yoga in this article:

There is no science to establish that the chakras or nadis have any basis in physical reality, except perhaps the obvious correspondence of the chakras and central nadi with the spine, and the loose identification of the ajna (third eye) chakra with the pineal gland.

This spiritual anatomy must therefore be assumed to be largely a mental construct until such time that clinical studies provide evidence otherwise.

While these visualizations and cognitive exercises are certainly of value, it should be remembered that the ultimate goal remains to practice mindfulness meditation and cultivate that state of mind called Samadhi, or enlightenment.