Back to The Mysteries and Science: Origins of Western Alchemy Part I

Magic and Science

Origins of Western Alchemy: Part II

The Dark Ages of Christian Europe

This article is a short introduction to the relationship between magic, alchemy, science and religion. It takes just a very brief peek at the dark side of the Christian religion in regards freedom of thought and scientific advancement.

The modern alchemist will note the holistic nature of the early alchemist’s worldview. They may begin to consider the reasons for secrecy in alchemical tradition.

Due to the cosmopolitan and eclectic philosophical atmosphere of advanced ancient Alexandrian culture, science, philosophy and art were shared and encouraged. This enlightened Alexandrian learning came to an abrupt halt after the pious Emperor Theodosius I banned pagan customs by an edict in 391.

With the force of the law behind them, a mob of law abiding, politically active Christians destroyed the greatest university of science and philosophy in the world at the time: the famous library and museum of Alexandria. Many invaluable manuscripts were destroyed, including rare works by Aristotle and other celebrated geniuses, which the world will never see.

The Dark Ages followed with the spread of Christian rule. This horrific era did not begin to disperse until the Renaissance of Classical “pagan” education and the rise of natural philosophy or science.

Following the split of the Church in the Reformation period was the decline of the power of the church over the state and the rise of the Enlightenment, the Age of Reason and the Scientific Revolution.

Under these banners arose constitutional government based on “Liberty, Equality and Fraternity.” It was this manner of relatively free and intellectually honest lifestyle that fueled the discovery and prosperity of the Industrial, Space and Information Ages.

Attack on “Pagan” Culture

When Theodosius I established the Roman Empire as Christendom in the late fourth century, he closed and outlawed the Eleusinian sanctuaries. The hostile Christian empire destroyed much of “pagan” culture, and to its eternal dishonor and shame, persecuted and hunted the non-Christian keepers of the ancient Mysteries to complete extinction. The “pagan” wisdom inspired later generations and societies, of course, and continues to inspire today.

Anyone who studied mathematics, science or medicine in the Middle Ages, the heyday of the Christian era, was under threat of being called a magician or conjuror, and a heretic. Therefore, during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance in Europe the ancient “pagan” magic was concealed, transmitted, and refined in the study of alchemy.

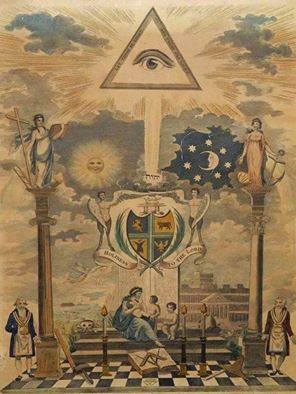

In the seventeenth century the English alchemist Elias Ashmole, the second known recorded Freemason and a founder of the Royal Society, offered an explanation for the concealment of mystical teachings in symbolic alchemical terms. It reminds one of the esteemed Masonic researcher William Preston’s[1] (1742 – 1818) same defense of the symbolism of Freemasonry.

Preston wrote that, like the priests that created the ancient Egyptian Mysteries, the wise founders wished to keep the sacred knowledge out of the hands of the profane.[2] ‘Profane’ in this context means uninitiated; not yet transformed by the direct experience of sacred knowledge.

Throughout the history of the world, internal alchemy has been cloaked in secrecy on principle alone, as part of a rite of initiation or as trade secrets, and it has been driven underground by more powerful and oppressive religious and political enemies.

The leading practitioners of symbolic alchemy have often joined the ranks of the numberless anonymi. The process of the mystical ascent is conveniently embedded in the allegorical language of chemistry and astrology, and symbolized by common chemicals and operations.

[1] William Preston, Illustrations of Masonry, 1772.

[2] Elias Ashmole, Theatrum Chemicum Brittanicum, 1652, Fascimile, Kessinger Publishing.

Origins of Western Magic

The original magician, magus (plural magi), or magos (plural magoi), was the Persian prophet Zoroaster who wrote the Hymns of Zoroaster in the seventh century BCE. His religion was adopted by Darius, King of Persia, and established as the state religion. The Persian priests were at that time called by the Greeks magos (Latin magus) and their practices called mageia (Latin magia), or magic.

The secret society of Persian magi with their secret rites eventually elicited general suspicion. The goetes, practitioners of goeteia, were anybody who practiced what the Greeks interpreted as supernatural powers, developing a bad reputation by being related to journeys to the underworld, mediumistic practices, necromancy, charms, and curses. They therefore were considered deceitful and scandalous.

Magic, the Persian institution, was considered to be almost as bad as goeteia, and though no clear definition of magic existed, the general practice was outlawed in polytheistic Classical Rome.

Graeco-Egyptian magical papyri written from the first to the fourth centuries CE reveal preparation periods that involve ceremonial purification and ritual instructions for the creation of vestments and furniture, such as the robe, the wand, incense, cakes and wine, milk and honey, oil, ink, and talismans. Long prayers, hymns, and invocations are used.

The magician with the greatest reputation among the Jewish people was King Solomon. Rabbinic legends associated him with talismans, magic words, control over demons, and such things. The Testament of Solomon was written in this period, which drew from Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Jewish, Persian, Greek and Christian sources such as the Book of Tobit, The Book of Enoch, and the Talmud, to form a list of spirits for use in evocation as a means of averting disease and other evils.

In fifth century Greece “magic” had became a broader term enveloping anything related to divination, sacrifices, use of drugs, talismans, or spells to acquire wealth or love or to destroy an enemy. It also included anything related to supernatural beings like ghosts, spirits, angels and demons, and secret rites in general.

Magic was associated not only with occult spirituality, but with cannibalism, incest, and other reviled practices. Still, the reputation of the magi continued to draw awe and respect throughout the centuries.

According to the Christians it was a number of the Eastern priests who first paid homage to Jesus ben Joseph as the King of the Jews, for Jesus was a reputed magus, and according to the Christians Jesus was the greatest magus of all time.

Though magic has not entirely shed its reputation of perversion, even into the twenty-first century, like every religion or philosophy, magic continues to attract healthy, moderate, and wise adherents, as well as extreme or devious individuals.

Holistic Worldview: Religion, Magic and Science

Magic was the medicine of Europe in the Dark Ages. The household magic word “Abracadabra” was used as incantation and talisman to dispel the demons of disease. Magicians produced spells and concoctions for the treatment of illnesses in Europe while the Arabs studied the Greek forms of medicine.

Pliny the Elder (23 – 79 CE) was the favorite historian of this era, astrology was the primary “science,” and in this milieu many ancient writings of value were mishandled and lost for all time.

As the Christian Church rose to supreme power in these times, believers depended upon miracles, if not magic, to heal them. Purported holy relics of Jesus and the saints of legend appeared across Europe. Monasteries grew therapeutic herb gardens and acted as hospitals when necessary.

When the study of Latin became mandatory in order to read the only available Bible, the Vulgate Edition, the European lettered classes became familiar with Classical Greek and Roman authors. Medieval monks, especially in Ireland, collected and translated ancient manuscripts, not destroyed by Christian militants or fire, into Latin. Thus a portion of Classical civilization was preserved for the dawn of the Renaissance.

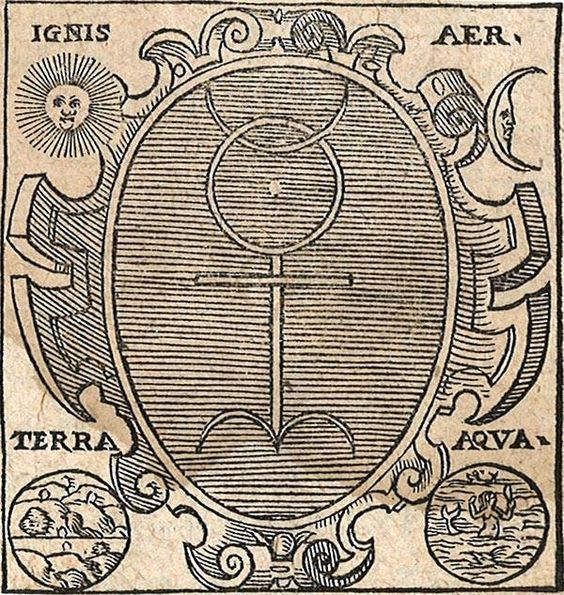

In the early days of science, thinkers did not separate science from spirituality. Until the nineteenth century, scientists maintained a holistic worldview that comprehended every aspect of experience and knowledge.

Copernicus revered Hermes Trismegistus, Tycho Brahe studied astrology, and Johann Kepler followed Pythagorean philosophy. Robert Boyle, Isaac Newton and Elias Ashmole were accomplished alchemists and early leaders of the scientific Royal Society. Ashmole was the second man on record to be made a Freemason.

All the more so integral was the understanding of the medieval alchemist and Renaissance magician. Renaissance magic was a mixture of syncretism, sacred geometry, and the physical sciences, or more accurately, proto-science.

Syncretism is the comparison and drawing analogies between mythologies and religious or philosophical ideas in order to demonstrate an underlying unity. Sacred geometry refers to Pythagorean or Neo-Platonic uses of mathematics to explain spiritual concepts.

Religion Wrestles With Modern Science

Science in the Dark Ages could get you killed. All knowledge and government was based on faith. Many great minds of the human race have known what it is like to live in fear of one’s life because one does not believe in certain religious superstitions. Anything that did not fall in line with the doctrine of the ruling Church patriarchs of the time was condemned as heretical or blasphemous, and punished with loss of property, liberty, limb and life.

Science was born under persecution. It is well known that the Church was oppressive of science and scientists when that hallowed institution possessed supreme power over society and government. The same holds true today under fundamentalist Judeo-Christian and Muslim governments over issues like climate change, evolution, family planning and sexual orientation.

History gives evidence that superstitious religion is ultimately incompatible with science. The central operation of religion – faith – is the very antithesis of unbiased scientific inquiry, the essence of the scientific world-view.

Religious scripture is not evidence of the supernatural; it is merely the claim. With so many contradictions between various religious claims, the reasonable mind has one obvious course, despite its own longings and leanings: an unbiased and relatively comprehensive investigation of world-views with the method of science. It will do this despite the dangers posed by its community and it is likely to seek to influence the community to its own unprejudiced view.

Those who are self-educated and self-actualized, or even just aware and honest, admit the many benefits and the fatal flaws of religious institutions. Every unimpeded observer will independently recognize the proper course for their own unique expressions of meditation, health and community.

From Honor to Taboo

Obviously, certain branches and theories of math and science were acceptable in medieval and Renaissance Europe. If it helped build empire and it did not offend the local religious superstitions or dogma it was safe to practice. Some governments even patronized alchemists for various political and economic benefits.

King Henry VI of England issued several patents to practice alchemy in the sixteenth century.[1] The German Wilhelm IV (1532 – 1592) and his son Moritz von Hessen-Kassel (1572 – 1632) were avid scholars, scientists and alchemists who surrounded themselves with the greatest sages of their time. They built the foremost laboratory in the world during their lifetimes.

Some royals during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance had their own court astrologer. Some magicians were given royal prerogative, such as Henry Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (1486 – 1535), one of the greatest magi in history. Agrippa was a self-proclaimed magus involved in occult societies and employed by the Emperor of Germany, Maximilian I.

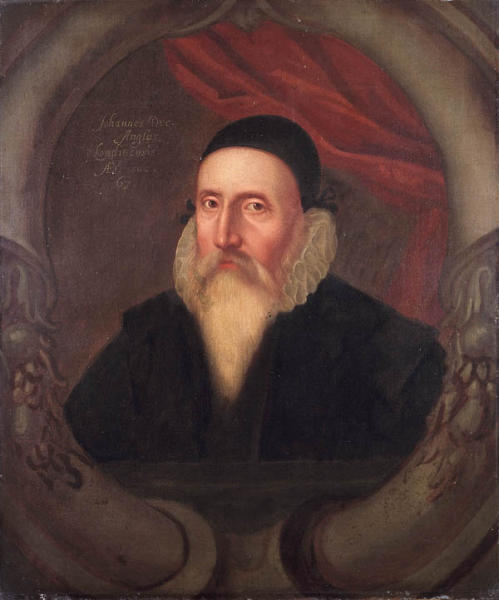

John Dee (1527 – 1609) was admired by the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian as well as his own queen, Elizabeth I of England. His Enochian Magic is often considered by modern magicians to be one of the most powerful ever known.

During the age of exploration, Dee became the world’s foremost navigational mathematician and the prophet of the British Empire, for which he helped lay the foundations. As tutor and advisor John Dee was appointed Queen Elizabeth’s Royal Adviser on Mystic Secrets.[2]

Yet, medieval magicians and alchemists like John Dee and Cornelius Agrippa were, despite rational argument, eventually tabooed by the propaganda of opponents of magic and science – even into the present day. Anyone who studied mathematics, science or medicine in the Middle Ages was under threat of being called a magician or conjuror, and a heretic. Of course it was worse when his interests led him to studies of a mystical sort, which transcended organized religion.

Francis A. Yates, the groundbreaking researcher in the field of the Hermetic-Kabbalistic tradition, speculated that the failure of the early Masonic fraternity to boast John Dee among its main influences was a result of a successful smear campaign against Dee and this kind of fear of association.

In fact, only in the last half-century have professional academics begun to take seriously the proto-scientists and the mystical and syncretistic writings of respected scientific minds like Aristotle, John Dee, Elias Ashmole and Isaac Newton.

Adapting to the social landscape, individuals or groups have been keen to conceal interests that do not conform to the current fashions of the Church and State.

[1] D. Geoghegan, “A Licence of Henry VI to Practise Alchemy,”

Allen G. Debus, Ed. Alchemy and Early Modern Chemistry: Papers from Abix,

The Society for the History of Alchemy and Chemistry, 2004, pp. 80-87.

[2] Benjamin Woolley, The Queen’s Conjurer, Henry Holt and Company, New York, 2001.

From Taboo to Honor

The Roman Inquisition arrested Galileo Galilei (1564 – 1642), the Father of Modern Science, under suspicion of heresy. The Church fathers at the time insisted that the earth was the center of the cosmos due to their interpretation of what they believed to be sacred scripture and the unerring word of their god. Galileo asserted the now undisputed heliocentric theory, which states that the earth and nearby planets orbit the sun.

Galileo’s accurate heliocentric theory was not just opposed in civilized debate, as theories are tested and reviewed in scientific circles. The scientist, himself, was locked up in a prison by those aggressive and deluded primates with collective superior physical power, whose group decisions were based on the superstitious content of their common faith. For the rational mind, life between earth and sun has been a traumatic experience, indeed.

Burned at the stake by the faithful flock of the Prince of Peace Jesus Christ for voicing heretical philosophical ideas, the Hermeticist Giordano Bruno (1548 – 1600) is the quintessential example of the martyr for religious liberty and free speech.

Bruno stands today deeply respected by scientists as a true martyr because he was burned at the stake, in fact, as a proto-scientist. His crime was his imperturbable unwillingness to sacrifice his personal and professional integrity to the prevailing dogma of the established Church.

The bloody histories of theistic religious formation and conflict, the era of the Crusades, the Inquisition, and the witch trials bear witness to the wanton violence of the indoctrinated. Unfortunately, history provides many such lamentable examples from an entire spectrum of religious actors in every part of the globe.

A standard of tolerance, empathy and peace has come only with the clarity of reason, the wisdom of a humanist worldview with its universal human rights, and of course, the insight and magic of science.

Back to The Mysteries and Science: Origins of Western Alchemy Part I