Ancient Roots

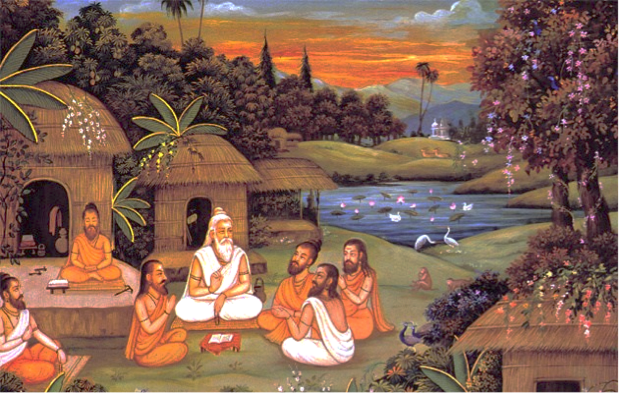

Ayurveda is the world’s oldest continuing system of medicine. It is the ancient form of Indian medical practice, which originated in pre-historic times, but is formally taught in the Tantras and the Samhitas.

Ayurvedic philosophy, remedies and techniques have been passed down generation after generation for three thousand years. Proponents call it allopathic medicine in contrast to mainstream modern medicine, which is evidence-based as defined by modern science.

The physical and mental exercises of yoga, arguably the central practice of Ayurveda, are still unsurpassed and have had an irrevocable impact on modern Western medicine. Yogic discipline has had an influence on hypnotism, chiropractic, and alternative or complimentary medicine like “Healing Touch.”

Western culture, itself, has fully absorbed yoga as a modality of health and meditation. A study of Ayurvedic philosophy is indispensable to an informed comprehension of modern holistic health.

The word Ayurveda, “the knowledge of life,” is the combination of the Sanskrit words ayur, “life,” and veda, “knowledge.” Ayurveda follows the cycles of nature that underpin human life and health.

Ayurvedic medicine recommends a daily routine (Dinacharya) that includes waking early before the dawn, a morning prayer, cleaning with and drinking water, morning evacuation and oral hygiene. Next comes the anointing with oil, wearing clean clothes, exercise, meditation and then a healthy breakfast. The daily routine should incorporate yoga and massage therapy. An early bedtime is also recommended.

The Daily Routine (Dinacharya)

The Ayurvedic World-View

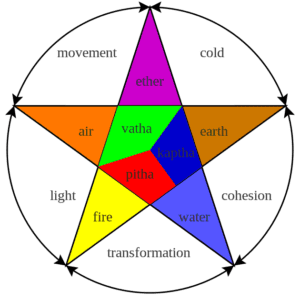

Ayurveda theorizes five basic elements: fire, water, air, earth and ether. The body is composed of three humors, bile, phlegm, and wind, produced by the action of the blood and body upon consumed food. The humors cause problems only when the humors are out of balance. Ayurvedic medicine aims to maintain and restore this balance with its holistic, preventative lifestyle and medicinal drugs.

The three humors correspond with the three dosha, forms of energy within the body: Pitta, which acts like fire, related to fiery temperament, intelligence, and activity, associated with the digestive system, the cause of inflammation and heartburn; Kapha, which acts like earth and water, related to growth, solidity and calm, associated with thte torso, the cause of obesity and diabetes; and Vata, which acts like air or wind, related to imagination and creativity, associated with respiration and circulation, the cause of disorders like constipation and anxiety.

A Scientific Explanation of the Three Doshas

Ayurveda divides the body into seven tissues (dhatus): plasma/lymph (rasa), blood (rakta), muscles (māmsa), fat (meda), bone (asthi), marrow/nerves (majja), and semen/reproductive (shukra). In diagnosis, practitioners use their five senses to examine patients in search of imblances. The eight methods of diagnosis are: Nadi (pulse), Mootra (urine), Mala (stool), Jihva (tongue), Shabda (voice/speech), Sparsha (skin/touch), Druk (eyes/vision), and Aakruti (face and body/appearance).

Treatment and prevention involve nutrition, herbalism, exercise, yoga and meditation. Dinacharya is the idea that life follows natural cycles and health depends on harmony with these cycles. Ayurvedic medicine determines healthy cycles of sleep, work, diet, exercise, yoga and meditation. Stress is laid on good digestion. Hygienic practices like bathing, oral health and skin care are also important.

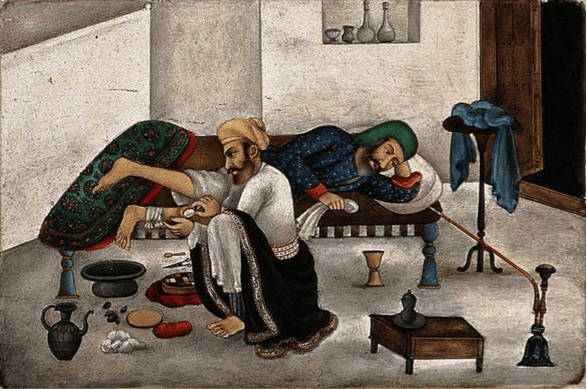

There are five treatments (Panchakarma) used to detoxify the body: Vamana (emesis, or vomiting), Virechana (anal purgation), Niroohavasti (decoction enema), Nasya (medication through nasal passages), and Anuvasanavasti (oil enema). Snehana and Swedana are the pre-procedures for Panchakarma. Snehana means oleation or anointing (massaging) with oil; Svedana is steam therapy or sun therapy.

The traditional ten arts studied by Indian medical students included chemistry, cooking, horticulture, metallurgy, and pharmacy. The eight branches of Ayurveda, the physicians’ art, were first described in the fourth century BCE epic called the Mahābhārata. Over time they were formalized as:

- Internal medicine

- Surgery

- Ears, eyes, nose and throat

- Pediatrics

- Toxicology

- Purification of the reproductive organs

- Health and longevity

- Psychiatry and spiritual healing

The Ayurvedic Diet

Diet is very important to the Ayurvedic preventative health regime. The Ayurvedic diet is vegan as determined by India’s religious dispositions. The doshas determine body and mind type. Vata is thin and energetic, prone to anxiety, Pitta is medium build, productive of “heat” and therefore susceptible to stress, and Kapha is larger, calm, but disposed to obesity.

The concept of “going on a diet” does not apply in Ayurvedic medicine. Diet is part of one’s lifestyle. One eats according to one’s body-mind type with the aim of balancing characteristics with opposite types of food. Meals are built around the six tastes: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, pungent, and astringent.

Foods and herbs are prescribed together therapeutically. Combinations of herbs are meant to address balances in a similar way to food. Herbal remedies constitute the principal preparations, but in the practice of rasa shastra, operative alchemy, prescriptions can include minerals like lead, sulphur and gold, or even arsenic. Certain rare medicines can include alcohol, opium or cannabis. Oil is a common ingredient in treatment, from concoctions, to ointments, to mouthwash.

The Ayurvedic theory that food and drugs should be consumed to balance the natural tendencies of the body-mind aligns with the philosophy of modern holistic science. Medical disorders that can be treated with drugs can very well be characterized as imbalances. Ignoring dietary health and proper drug use is detrimental to physical and mental health and can have destructive effects on all aspects of life. The importance of diet and healthful drug use cannot be overstated.

While the traditional concepts and prescriptions of the Ayurvedic diet and use of substances may not be grounded in fact, the recognition of the effects of diet on physical and mental characteristics has been confirmed by modern science. Human physiological health does, indeed, as traditional medicine suggests, depend on a balanced chemistry.

Food and drugs contain chemicals, and when consumed some foods, like pure chemicals, can aggravate negative moods, like depression, stress and anxiety; other foods and drugs have calming effects or contribute to strength or energy. Severe effects are observed when an element as simple as water is depleted; there is headache pain, lethargy and subsequent bad mood when one is dehydrated.

Many foods contain sugar, a carbohydrate, which may contribute to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, while sugars like sucros or glucose can increase energy levels for about two hours, followed by a slump, and starch has the same slump effect. Protein has varying effects on people’s mood depending on gender and age. Vitamins like B12 and minerals like folic acid have significant effects on depression and other moods. Alcohol has very noticeable effects on mood both short-term and the day after over-consumption. Tea and coffee, of course, contain caffeine, a stimulant.

More Information on the Ayurvedic Diet

DASH diet and Mediterranean diet for heart health, to combat high blood pressure.

Vegan diet, Low Carb diet and Paleo diet for weight loss and improved heart health.

The best diet according to science

Examples of herbal remedies according to the science.

Ayurvedic Medicine

Ayurvedic massage is called Abhyanga. It is primarily used to aid circulation of the blood through the vessels, a function of the cardiovascular system, and it is good for the immune system and the skin. It may also be utilized for relaxation, stimulation, pain reduction and mobility. Massage is done with oil (like sesame, sunflower, olive, or several others), ghee (clarified butter) or an herbal compound (powder, paste or oil).

Abhyanga may be performed by one or two therapists. Types of massages are often divided into three categories: full body massage, head massage and foot massage. It may be done alone or it may be followed by panchakarma therapy, yoga or a warm bath.

The Indian government promotes research into non-allopathic medicine in institutions of higher education via the Ministry of Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy (AYUSH) and its subordinate body, the Central Council of Indian Medicine (CCIM). This author looks forward to the Indian government removing pseudoscience, systems, ideas or techniques posing as and mistaken for science, from its ministries. This will include aspects of traditional Indian medicine, a large share of naturopathy and the whole system of homeopathy.

Naturopathy is a collection of alternative and pseudoscientific health modalities, mixing legitimate holistic health practices with quackery of all stripes. Samuel Hahnemann invented homeopathy in 1796 on the similia similibus curentur (“like cures like”) theory. Homeopathy has been scientifically proven to be an ineffective form of treatment. It is a pseudoscience and is in fact based on the principles of sympathetic magic.

Unani is based on the classical four humors of ancient Greece, Phlegm, Blood, Yellow bile and Black bile; the phycisians Hippocrates and Galen (Yūnānī means “Greek”); and The Canon of Medicine by the eleventh century Persian physician Ibn Sina, or Avicenna, prevalent in India by the thirteenth century. Unani incorporates Ayurvedic and Traditional Chinese Medicine with this ancient teaching to produce a system of balancing humors with diet, aromatherapy, drugs and surgery.

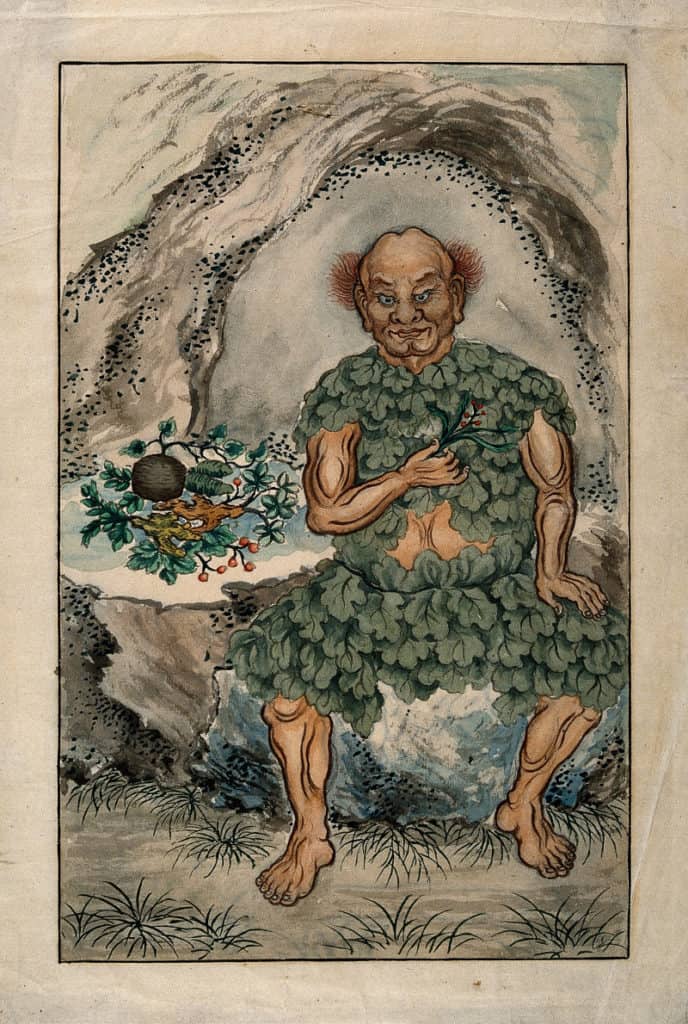

Siddha medicine originated with the siddhars, ancient Indian sages with eight supernatural powers known as the ashta siddhis. The first siddhar was Agastyar, the guru of the others, who acquired siddha from Murugan, the son of Shiva and Parvati. Siddha views the health of the body as contingent upon the health of the soul. Siddhars developed themselves into enlightened immortal beings with yoga, meditation and fasting.

Siddha diagnosis involves checking eight aspects of the body: tongue, skin color, skin temperature and moistness, voice, eyes, nose, stool, urine and pulse. Treatment aims to keep the three humors in equilibrium through diet, drugs and a holistic lifestyle regimen. Surgery, heat, leeches or blood letting may be involved. Other therapies include purging, fasting, steam and sunlight.

The history of Ayurveda is a story of centuries of building on ancient tradition. New techniques were acquired when they became available and older methods with doubtful value were abandoned. With the introduction and adoption of modern scientific method and modern medicine from the West, Indian healthcare took a leap forward, and Indian doctors have made significant contributions to Western medicine.

The benefits of Indian medicine have not yet been fully realized outside of India. The burden of comparing, contrasting, updating and harmonizing Eastern and Western teachings remains on the shoulders of future generations. It is our duty today to contribute to the process and encourage this noble endeavor.

Origins of Ayurveda

“The First Meditators: Indian Yoga”

The ancient Vedic magicians healed through spells and incantations against evil spirits and evil magicians, as evidenced in the earliest Vedas. Brahmin priests were the physicians until the Muslim conquest of India, about the turn of the first millennium. The Brahmins were adept surgeons and pharmacists, but while their spiritual anatomy was quite extensive, physical anatomy was lacking.

India has been a land of diverse ideology, but the first and principal manuscripts on Indian religion, the Vedas, have had an effect on every one. The Indian Vedic hymns were written in the sixteenth century BCE but are speculated to be based on ideas prominent 2,500 BCE. The Vedas were formed historically in a natural progression from polytheism to monotheism to, in the Upanishads, monism. There are four Vedas, each of which contains hymns, ritual and sacrificial duties, and philosophical writings.

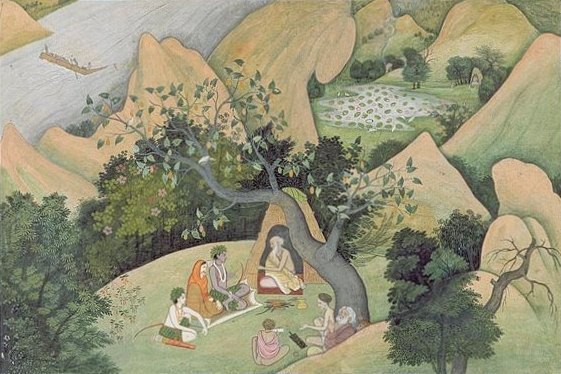

The Vedas introduced the practice of magic. Also, they set the foundation of the social order that was to persist to the twenty-first century, which encourages the aged householder to retire to the forest, and the forest-dweller to practice meditation. The oldest Veda is the Rig Veda, ancient hymns about the gods, around which the later Vedas are based, written as early as 1,500 BCE.

The Yajurveda focused on ritual, the Samaveda expressed scripture as chants, and the Atharvaveda, written around 1000 BCE, is the earliest Indian medical text. It is a collection of hymns teaching magic, religion and medicine for daily life, which describes how to heal disease by destroying evil spirits through magical spells.

Experts assert that early Indian medicine recognized fever, cough, consumption, diarrhea, dropsy, abscesses, seizures, tumours, leprosy and other medical disorders. Treatments included herbal remedies, plastic surgery, treating fractures, amputations, stitching of wounds and other forms of surgery.[1] Yogic philosophy developed to become more systematic in the literature of the Epic Period and the sutras.

[1] Underwood and Rhodes, “History of Medicine,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 2008

The Epic Period

From “The First Meditators: Indian Yoga”

The Epic Period of Indian philosophy occurred from 600 BCE to about AD 200. The Ramayana and Mahabharata (with the famous yogic Bhagavad-Gita) were written and the people turned to the reverence of the god Shiva; the god Vishnu and his incarnations as Krishna or Rama; or the teachings of the Buddha. This was also the period of Zoroaster in Persia; Pythagoras, Socrates, Plato and Aristotle in Greece; and Confucius and Laozi in China.

The Epic Period produced the Ramayana, Samkhya, the Mahabharata, the Laws of Manu, and the Dhammapata of the Buddha. The Ramayana was the epic poem of King Rama, the incarnation of Vishnu, and the Mahabharata contained the popular Bhagavad-gita, the first comprehensive treatise on yoga. At the turn of the millennium the sutra literature appeared, manuals of philosophical rules or formulas, like Patanjali’s system of yoga in the Yoga Sutra.

The legendary Kapila, of divine origin, is said to have invented the philosophy of Samkhya, which was the first real system of contemplation. Whereas yoga would later seek liberation from ignorance and suffering through meditation and exercise, Samkhya taught liberation through knowledge. It taught that the world is the maya, or cosmic illusion, which exists due to ignorance.

The practitioner’s goal is moksha, to release himself from karma, the effect of one’s actions, or destiny, and from the cycle of transmigrations of the soul, or reincarnation. Suffering leads to a yearning for salvation, until even pleasure is pain because it is followed by pain.

The aim of Samkhya is the separation of purusa, self or spirit, from prakrti, nature; the isolation of the essence of oneself from all that is not the self. The spirit contemplates itself; it withdraws from matter into itself, and all elements that are not the spirit are reabsorbed into nature. Liberated, the material body continues but the personality has escaped. Thus the man lives out his karmic existence until he dies and his spirit is annihilated. Only when the last sentient being has attained salvation will the universe be reabsorbed into its original substance.

According to Samkhya philosophy, the universe and man may be divided into three gunas (“thread,” “virtue” or “quality”), or modes of being. Tamas is inertia, rajas is energy or passion, and sattva is goodness. The goal is to find the balance, which is sattva. The Bhagavad-gita names this goal yoga, and presents the yogin as the supreme person. It sets forth the discipline of yoga somewhat more systematically than the literature before it, to teach one how to accomplish and perpetually maintain mystical revelation even in daily activity.

The Bhagavad-gita presents the yogin as the supreme person. It sets forth the discipline of yoga somewhat more systematically than the literature before it, to teach one how to accomplish and perpetually maintain mystical revelation even in daily activity. The Indian sage has long practiced yoga, the method of uniting the divine and the earthly.

Brahman’s spirit, the prana or life-force, is the substance of Creation. The cultivation of prana is done by consistent study and contemplation of the Vedas and later philosophical texts called the Upanishads, the Mahabharata, and the Sutras. Prana is cultivated through breathing exercises, postures, and mental exercises, diet, holistic medicine and a natural lifestyle.

The Great Triad and Other Core Texts

The Bṛhat-Trayī, “The Great Triad,” is a nineteenth century reference to the three primary encyclopedias of early Sanskrit medicine in relation to the Laghu-Trayī or “Lesser Triad,” of later medical encyclopedias. The Great Triad is composed of:

- Charaka Samhita by Agnivesa (8th century BCE) and later edited by Charaka (c. 6th century BCE)

- Sushruta Samhita by Sushruta (6th century BCE)

- Ashtanga Hridayam Samhita by Vagbhata (c. 7th century CE)

The Great Triad is associated with the “Trinity” of Ayurveda: Charaka the forefather, Sushruta the surgeon, and Vagbhata, the later great physician. Charaka is known as the “Indian father of medicine.” He invented the concepts of the three doshas and the three humors. He taught that the humors must be balanced with a healthy lifestyle and preventative modalities. Disorders were imbalances among the three doshas, which could be addressed by medicinal drugs.

Charaka edited a medical encyclopedia written earlier by Agnivesa under the supervision of the renowned rishi Atreya Punarvasu, which became a standard textbook of Ayurveda under the title Charaka Samhita. The fourth – sixth century Bower Manuscript, a compilation of seven treatises on medicine, divination and magic, contains a later version of the text. The manuscript is preserved in the Bodleian Library collections at Oxford.

According to Charaka tradition, the six schools of Ayurveda originated with the six disciples of Atreya: Agnivesha, Parashara, Harita, Bhela, Jatukarna and Ksharpani.

While the Charaka Samhita became an authority on medicine in general, the Sushruta Samhita became known as the textbook for surgery. Both medical encyclopedias covered core subjects such as anatomy, pathology, therapeutics and pharmaceuticals. The Sushruta Samhita was still very much a part of Hindu religion and philosophy.

The author, Sushruta, is by legend the son of Dhanvantari, the Hindu god of medicine. The Sushruta Samhita recommends the study of the Vedas as a part of preventative health and holistic healing. It reveres the gods and adheres to Indian philosophical concepts.

The Ashtanga Hridayam Samhita (“The Heart of Medicine”) references the Charaka Samhita and the Sushruta Samhita. It, too, mentions the gods, specifically Lord Shiva, and its author, Vagbhata, is by legend the son of a Vedic monk by the name of Avalokita. His descendents were likewise Vedic. He is traditionally the author of another work,

The Aṣṭāṅgasaṅgraha (“Compendium of Medicine”), which has been shown by experts to be the work of a different author. The root word “Ashtanga” in these manuscripts is a reference to the eight branches of Ayurvedic medicine. The Ashtanga Hridayam Samhita is India’s most thorough and popular classic on medicine.

The Laghutrayi (Lesser Triad) consists of several smaller works bundled into three sets. The Kiratarjuniya, Sisupalavadha and Naisadhiya, form the great triad of mahakavya, or epic poetry. This is complemented by the two mahakavya (epic poems) of Kalidasa: the Raghuvamsa and Kumarasmbhava. These are combined with either the Meghaduta (The Cloud Messenger) or Bhatti’s Ravanavadha (The Killing of Ravana), known as the Bhattikavya, to form the Lesser Triad.

The Agnivesha Samhita was written around 1500 BCE by the legendary rishi Agnivesha, disciple of Punarvasu Atreya, and later edited by Charaka. The 6th century BCE Kasyapa Samhita is known for the treatise of Jivaka Kumar Bhaccha. The Harita Samhita quoted by Vagbhata and later commentators up to the sixteenth century is no longer extant. The extant Pseudo-Harita Samhita is attributed to the disciple of Atreya Punarvasu, but is the work of a later author probably in the twelfth century CE.

Other Ayurvedic textbooks include the Astanga Nighantu by Vagbhata, Paryaya Ratnamala (c. 9th century) by Madhava, Siddhasara Nighantu (c. 9th century) by Ravi Gupta, Dravyavali (c. 10th Century), and Dravyaguna Sangraha (c. 11th century) by Cakrapanidatta, the Cakradatta, the Sahasrayoga, the Vrndamadhava, the Gadanigraha, the Vangasena, the Cikitsakalika, the Kaksaputatantra, and works compiled by Dalhana (c. 1200), Sarngadhara (c. 1300) and Bhavamisra (c. 1500).

The Yoga Sutra

From “The First Meditators: Indian Yoga”

After the Epic Period came the sutras, systematic and critical philosophical discussions and debates, and the scholastic commentaries upon them. This philosophical productivity in India started about the time of Christianity in the West, and continued until the sixteenth century, when Arab Muslim and then British Christian invaders persecuted and subdued Aryan Indian culture.

The sutras were manuals of philosophical rules or formulas, like Patanjali’s system of yoga in the Yoga Sutra, written probably between the second and fourth centuries BCE. Previous philosophical literature was systematized and exposed to critical interpretation. Following this period, scholastic study of Indian philosophy has been the rule.

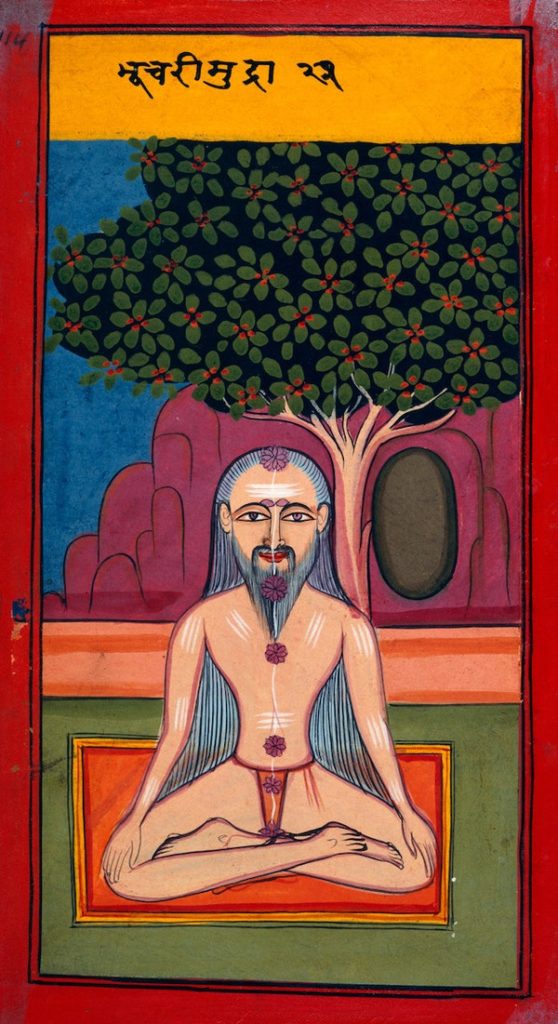

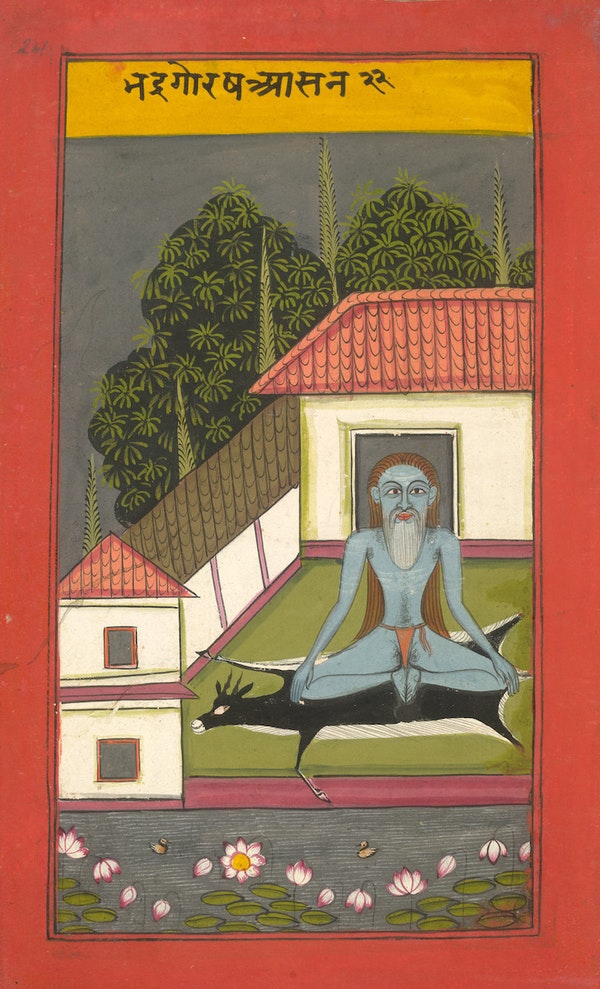

The Yoga Sutra by Patanjali describes an even more methodical system of enlightenment than that developed by the Buddha. Yoga shares with Samkhya the goal of the separation of purusa and prakrti. The Yoga system is thus a purification and a return to the original state of being. Yoga encompasses the yogin’s entire life as an ethical code and health regimen as well as a meditative discipline.

The aim of meditation is complete samadhi, a state of concentration or trance, and contemplation, which leads to enlightenment. The calming effects of ethical conduct and a degree of health help to facilitate meditation. Yoga introduced special postures and breath control exercises to aid concentration. All forms of Yoga begin with Astanga, the eight limbs, or preparations. In Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras the eight limbs of raja, royal or classical, yoga, are part of a single process that sets the foundation for true meditation.

- Yama – virtue, moral code of conduct; which includes respect for all living beings, honesty, restraint of envy, lust, and impatience, moderation of diet, simplicity, purity, and loving-kindness;

- Niyama – religious observances; which includes ritual purification, charity, study of the scriptures, worship, mantra, sacrifice and other religious observances

- Āsana – posture

- Pranayama – breathing exercises; regulation of breath and life-force

- Pratyahara –subjection of the senses; withdrawal of the senses of perception

- Dharana – concentration; one-pointedness of mind

- Dhyana – silent meditation

- Samādhi – ecstasy; tranquility and holistic awareness

The physical and mental exercises of yoga are still unsurpassed, and have had an influence on modern Western medicine, i.e., hypnotism, chiropractic, and alternative or complimentary medicine like “Healing Touch,” no less than on Western culture, itself, which has fully absorbed yoga as a modality of health and meditation.

Tantric Yoga

From “The First Meditators: Indian Yoga”

Tantric Yoga, developed in the sixteenth century CE, seems particularly concerned with anatomy, which is largely spiritual. Tantra applies the three gunas to energy, as causal, subtle, and gross, and to man, as sat, will (or transcendental consciousness), chit, knowledge (or mind), and ananda, action (or matter.) These three qualities are symbolized respectively, as sun, fire (the underlying element of the universe), and moon.

The causal, subtle, and gross levels of existence are, respectively, the causal forces that exist eternally and immutably, the subtle architecture of the whole of existence, and the gross elements of nature. Human existence on these planes is defined as bindu, nada and bija or will, knowledge and action. The triune concepts of Idea, Word (Logo) and Action of Classical Greek philosophy run parallel to the tantric model.

The tantrist imagined that the god Shiva was the essence of being, formless and unchanging truth. He was consciousness and bliss who desired manifestation, and thus, as first cause, created the universe, illusion (maya), a contraction within the pure and perfect self. When Shiva’s third eye opens, the universe will be destroyed.

The tantrist’s goal is transcendence of maya, supreme consciousness, the dissolution of self in other. The god manifested as thirty-six kinds of energy, or tattvas, which include aether, air, fire, water, and earth; anatomy and bodily functions, the senses, and four states of consciousness.

Chakras

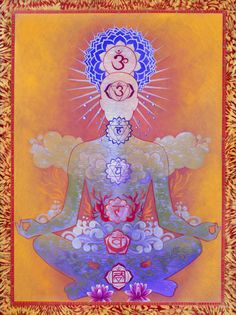

Each kind of energy is contained in a number of central locations called chakras, or disks, along the spine of the human being. Chakras may number seven, eight, or more, depending on the source of information. Prana, vital energy or life-force, manifests through the breath.

The chakras are centers of prana, as fourteen principle nadis are channels of prana. The prana of Shiva is causal, the chakras and nadis are subtle, and nerves and blood vessels are gross. The seven chakras are associated with specific symbols, flower petal numbers, colors, sounds, gods and physical elements:

Sahasrara, crown chakra located at the crown of the head – self-realization

Ajna, guru or third-eye chakra located between and slightly above the eyebrows – non-duality

Vishuddha, throat chakra located at the base of the throat – space or aether (akasha);

Anahata, heart chakra located in the heart – air

Manipura, solar plexus or navel chakra located in the abdominal region – fire

Svadhishthana, sacral chakra located at the root of the reproductive organ – water

Muladhara, root chakra located at the base of the spine – the element of earth

The three chief nadis are the central susumna, the “feminine” or “moon” ida to the left, and the “masculine” or “sun” pingala to the right. The nadis begin at Muladhara, the “root-support” chakra at the base of the spine, and meet at Ajna, the chakra at the yogin’s “third eye.” At the base of the spine is where the “coiled serpent” of Kundalini energy rests.

Kundalini is the energy of consciousness which is created when prana is transformed through tantric meditation. Breathing techniques purify the nadis and the chakras. Similar to monastic chanting, mantra, the ritual repetition of sounds, words, or phrases, is used to raise the Kundalini to open the “third eye” chakra of the yogin.

The first mention of the seven chakras is provided in the Vedas. The Rig Veda Mandala Eight, Hymn 28, Verse 5 may be interpreted as a reference to the chakras:

- THE Thirty Gods and Three besides, whose seat hath been the sacred grass,

From time of old have found and gained.

- Varuna, Mitra, Aryaman, Agnis, with Consorts, sending boons,

To whom our hymn is addressed:

- These are our guardians in the west, and northward here, and in the south,

And on the east, with all the tribe.

- Even as the Gods desire so verily shall it be. None ‘minisheth this power of theirs,

No demon, and no mortal.

- The Seven (gods) carry seven spears; seven are the splendours they possess,

And seven the glories they assume.

(From The Rig Veda (1896), translated by Ralph T. H. Griffith.)

The chakras appear in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, written some centuries before the 4th century CE. There are twenty Yoga Upanishads in the Vedas, composed after the Yoga Sutras. Early Yoga Upanishad texts that describe the chakras include the Darshana Upanishad, the Yogashikha Upanishad and the Shandilya Upanishad. Written in the tenth century, the Sat-Cakra-Nirupana, and the Padaka-Pancaka, translated in 1919 by John Woodroffe in The Serpent Power: The Secrets of Tantric and Shaktic Yoga, and the Gorakshashatakam, are guides to meditating on the chakras.

Hatha Yoga and the Chakras

The fifteenth century classic Hatha Yoga Pradipika[1] tells that Shiva is the divine patron of Hatha Yoga, a science belonging to Raja Yoga, or Royal Yoga, the Astanga or Classical yoga. Shakti, the consort of Shiva, bestows her wisdom and power upon the yogin who cycles life-force up and down the spine and concentrates on the Absolute.

This science of postures and visualizations was meant to be kept secret and passed along from guru to disciple. Once the yogin is adequately trained by the guru, he is to begin his endeavors in a secluded, well kept hut, situated in a peaceful and affluent location.

With a mutual concern with the health of body and immortal soul, the influence of alchemy on Hatha Yoga is clear in symbolism, as well as in method. The yogin is to eat moderately, socialize little and conserve energy.

The supreme posture is Siddhasana, sitting in half lotus position, chin on chest, looking steadily at the third eye. In Hatha Yoga the sun and the moon are symbols for various opposites, for example, in the alchemical union of the three channels of life-force upon the spine, Pingala– sun, Ida– moon and Shusumna– fire.

The union of opposites upon inhale results in youth, immortality even, and a death-like state of meditation even before the exhale. The alchemical elixir is called soma, essence, nectar, or liquor, and falls from the top of the head to shower the yogin’s spiritual anatomy in the panacea of the alchemical operation.

Written in the fifteenth or sixteenth century by an anonymous author, the Shiva Samhita, or Corpus of Shiva, is one of the three great works on Hatha Yoga, with the Gheranda Samhita and the Hatha Yoga Pradipika. It is a work of physiology and visualization of a spiritual anatomy.

The later Yoga Upanishads written in the 15th and 16th centuries also mention the chakras and their locations. The early practical guide on yoga and Kundalini, the Yogatattva Upanishad, describes early tantric anatomy and technique to meditate upon the chakras to attain Samadhi. The Yogakundalini Upanishad, as is evident by its name, is a fundamental treatise on Kundalini Yoga.

The locations of the familiar seven chakras or psychic wheels of Indian Kundalini yoga serve well as foci for concentration in visualization. These are explained as spiritual nerve centers as such, along the middle channel of three psychic channels down the length of the spine, which branch out into networks of smaller psychic nerves throughout the human anatomy. The relative cumulative effects on the brain and quality of life of this construct and alternative constructs should be the subjects of active scientific observation.

Where the chakras are described in the Shiva Samhita, the seventeenth century hatha yoga classic, so are described the three gunas or qualities sattva, rajas and tamas, the forces of harmony, energy and gross matter/inertia. These are identified symbolically with fire, the sun and the moon.

The elixir of immortality is said to flow continuously from the highest chakra, the thousand-petalled Sahasrara at the top of the skull. Every student of Ayurveda, traditional Indian medicine, is familiar with the chakras and the gunas.

[1] Akers, Brian Dana. The Hatha Yoga Pradipika, the Original Sanskrit Svatmarama, An English Translation Brian Dana Akers. YogaVidya.com LLC. 2002.

Ayurveda and Modern Science

One particularly helpful resource is PubMed, the bibliographic database for the biomedical literature of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) located in Bethesda, Maryland. The NCBI belongs to the United States National Library of Medicine (NLM), a division of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Information may also be found with the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), previously the National Center for Complementary Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), another division of the NIH. The Arya Vaidya Pharmacy and other organizations are active in advocating the scientifically proven benefits of Ayurvedic medicine.

Studies have indicated that Ayurvedic medicine may have some positive effects in the treatment of schizophrenia.

Studies have been done attempting to show the effectiveness of Ayurveda on various disorders, such as diabetes, which have not shown any conclusive evidence of such efficacy.

Turmeric is an ingredient often found in Indian cuisine. Many studies have been done on the substance cucurmin, found in tumeric due to its being used in traditional Eastern medicines to treat inflammation, digestive disorders and skin problems. There are also claims that the substance can assist in the prevention or treatment of certain kinds of cancer. Turmeric has been shown to have positive effects on certain conditions as well as contraindications. Studies have so far been inconclusive insofar as all the effects of tumeric on humans.

Ayurvedic herbal treatments may be as effective at countering rheumatoid arthritis symptoms as Trexall (methotrexate).

Ayurveda and Rheumatoid Arthritis 1

Ayurveda and Rheumatoid Arthritis 2

The Ayurvedic remedy frankincense, the dried resin of the Boswellia tree, can help manage pain in osteoarthritis patients.

Frankincense and Osteoarthritis

Yoga has been shown to improve quality of life, moderate anxiety and help control the symptoms of heart disease and hypertension.

Ayurveda, Yoga and Cardiovascular Diseases

Panchakarma may have a positive role in changing behavior patterns to a healthier lifestyle.

Panchakarma for a Healthy Lifestyle

While the benefits of the Ayurvedic regimen are apparent and yet still being revealed, some traditional treatments include ingredients that are definitely toxic or untested and potentially unsafe. Ayurvedic products sold in the United States are regulated as dietary supplements rather than pharmaceuticals. It is advisable to use caution when ingesting substances that produce unknown consequences. More scientific research needs to be done on certain Ayurvedic medicines.

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health’s (NCCIH) fact sheet

“Using Dietary Supplements Wisely.”

A 2008 study of 193 Ayurvedic remedies found that 21% contained hazardous levels of lead, mercury or arsenic. Lead poisoning has been found in pregnant women using Ayurvedic medicine form India. This could be due to improper manufacturing or other causes unrelated to proper Ayurvedic medicine. The point is that consumers need to be careful in choosing their source of Ayurvedic products as they would in purchasing any unregulated product to be ingested.

Lead, Mercury and Arsenic in Ayurveda

Lead Poisoning in Pregnant Women Using Ayurvedic Remedies from India

More Information on the Science of Ayurveda with Bibliography

Toward a Holistic Medicine

The World Health Organization (WHO) developed its own plan to help advance traditional medicine, including Ayurveda. The first WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy was created in 2002. The World Health Assembly (WHA) has since made a declaration and passed a resolution on traditional medicine, the 2008 Beijing Declaration on Traditional Medicine and the WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy 2014 – 2023 (WHA 62.13).

The WHO, WIPO, WTO Trilateral Cooperation on Public Health, IP and Trade also considers traditional medicine in its resolve to improve cooperation on public health issues. These agreements encourage national governments to adopt or improve strategies concerning traditional medicine. They promote education, research and clinical inquiry into traditional medicine and communication between traditional and mainstream health care providers.

WHO 2002 – 2005 Traditional Medicine Strategy

WHO 2008 Beijing Declaration on Traditional Medicine

WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy 2014 – 2023

WHO, WIPO, WTO Trilateral Cooperation on Public Health, IP and Trade

Using the dietary supplements or herbal and mineral remedies of Traditional Chinese Medicine or Ayurveda should be done with great care. Just because something can be labeled “natural” does not mean that it is necessarily safe. All ingredients may not be disclosed and some of these treatments may contain toxic levels of lead, mercury or arsenic. Interactions with other medications may be harmful, especially for pregnant or nursing mothers and children.

Special diets, purification methods, massage and other modalities may also have unintended effects. Unless a licensed physician prescribes otherwise, it is best to maintain a balanced diet that exceeds the minimal standards suggested by national government entities, like the American Food and Drug Administration.

In general, a balanced diet includes vegetables and beans, fruit, grains, lean meats (or tofu, nuts and seeds) and dairy. Regular exercise can be as little as a half hour a day, five times per week, with moderate exertion. Massage Therapy can be relaxing, energizing and therapeutic for the muscles.

The practices, things, foods and drugs that do harm to health are profane and unholy in the realm of holistic medicine. The practices, things, food and drugs necessary to holistic health are considered to be sacred. In this way science is a unique method that serves human interaction with the sacred.

A scientific community eager to adopt the benefits of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Ayurveda will need to do more controlled clinical trials to test for safety and effectiveness. Some research has shown that certain remedies help with pain, arthritis, inflammation and digestive disorders.

It remains for another great classic of the science of Ayurveda to be written. A complete catalog of traditional Eastern remedies and their effects would be a logical step toward greater public knowledge and better holistic living. This is a great opportunity for ambitious young physicians and scientists interested in holistic health.

Western Scientific Medical Research on Ayurveda

Western Scientific Alternative Medicine Research on Ayurveda

Scientific Introduction to Ayurveda (NCCIH)

More on Ayurveda and Science: NCBI

More on Ayurveda and Science: Livescience

More on Traditional Chinese Medicine and Science: Science Magazine

More on Traditional Chinese Medicine and Science: Journal of TCM

Learn more about modern Ayurveda

Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine: TCM & Ayurveda