Table of Contents

- Introduction – The Invisible Threads of Modern Life

Overview of wireless communication and its centrality in modern life. - What Is Wireless Communication?

Definitions and physical basis (electromagnetic waves, frequency, modulation, bandwidth). - Radio Transmission

- 3.1 History and Development

- 3.2 How It Works (AM/FM, antenna, modulation)

- 3.3 Frequency Ranges and Applications

- 3.4 Strengths and Limitations

- 3.1 History and Development

- Satellite Transmission

- 4.1 Introduction to Satellite Communication

- 4.2 How It Works (uplink/downlink, geosynchronous orbit, transponders)

- 4.3 Types of Satellites (LEO, MEO, GEO)

- 4.4 Coverage, Delay, and Cost Considerations

- 4.1 Introduction to Satellite Communication

- Wi-Fi (Wireless Fidelity)

- 5.1 Basics of Wi-Fi Technology

- 5.2 How It Works (routers, access points, signal propagation)

- 5.3 Frequency Bands (2.4 GHz vs. 5 GHz vs. 6 GHz)

- 5.4 Standards (IEEE 802.11a/b/g/n/ac/ax)

- 5.1 Basics of Wi-Fi Technology

- Comparative Analysis Table

Side-by-side chart of key parameters:

- Frequency range

- Bandwidth

- Range

- Latency

- Power consumption

- Mobility

- Infrastructure requirements

- Use cases

- Frequency range

- Applications and Use Cases

- 7.1 Radio: Broadcasting, emergency services, amateur use

- 7.2 Satellite: GPS, remote access, space communications

- 7.3 Wi-Fi: Local networking, IoT, home and enterprise use

- 7.1 Radio: Broadcasting, emergency services, amateur use

- Future Trends in Wireless Communication

- 8.1 5G/6G and satellite integration

- 8.2 Wi-Fi 7

- 8.3 Internet of Things (IoT) convergence

- 8.4 Edge computing and low-latency applications

- 8.1 5G/6G and satellite integration

- Conclusion – A Spectrum of Solutions

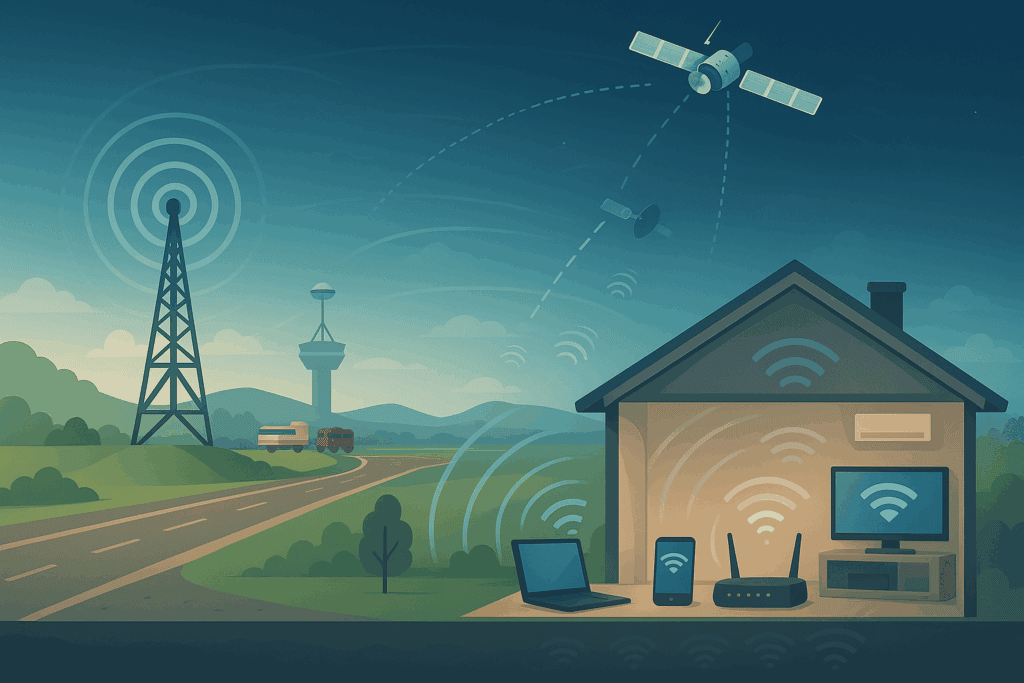

1. Introduction – The Invisible Threads of Modern Life

From the crackling airwaves of a 1930s radio broadcast to the seamless internet connectivity in a smart home, the magic of wireless communication surrounds us—unseen, yet essential. These technologies transmit our voices, data, music, and memories across vast distances without a single physical wire.

At the heart of this marvel lies the harnessing of electromagnetic waves, choreographed into distinct systems—radio, satellite transmission, and Wi-Fi—each tailored for particular needs and environments.

Though all three rely on the same fundamental physics, they differ greatly in design, range, bandwidth, cost, and application. Radio communication powers everything from local FM stations to two-way walkie-talkies.

Satellite transmission enables global navigation, weather forecasting, and internet access in the most remote corners of the Earth. Wi-Fi, in contrast, fuels the dense web of home, office, and public networked devices, forming the backbone of the modern digital lifestyle.

Understanding how these technologies work—and how they differ—is crucial in an age increasingly defined by wireless connectivity. This article compares these three pillars of wireless transmission, explaining their internal mechanics, strengths and weaknesses, and their roles in the evolving landscape of global communication.

2. What Is Wireless Communication?

Wireless communication is the transmission of data or signals between two or more points without the use of a physical medium such as wires or fiber optics. Instead, it relies on the propagation of electromagnetic waves through air, vacuum, or other media to carry information. This fundamental capability underpins nearly all forms of modern connectivity, from handheld radios to interplanetary satellites.

2.1 The Physics of Wireless Transmission

At its core, wireless communication is governed by Maxwell’s equations, which describe how electric and magnetic fields propagate as waves through space. These electromagnetic waves travel at the speed of light and can vary in frequency, wavelength, and amplitude. The electromagnetic spectrum encompasses a vast range—from extremely low frequencies (ELF) used in submarine communication to gamma rays used in medical imaging.

For communication purposes, the most relevant ranges are:

- Radio waves (3 Hz – 300 GHz)

- Microwaves (300 MHz – 300 GHz)

- Infrared and beyond (for certain optical or near-field systems)

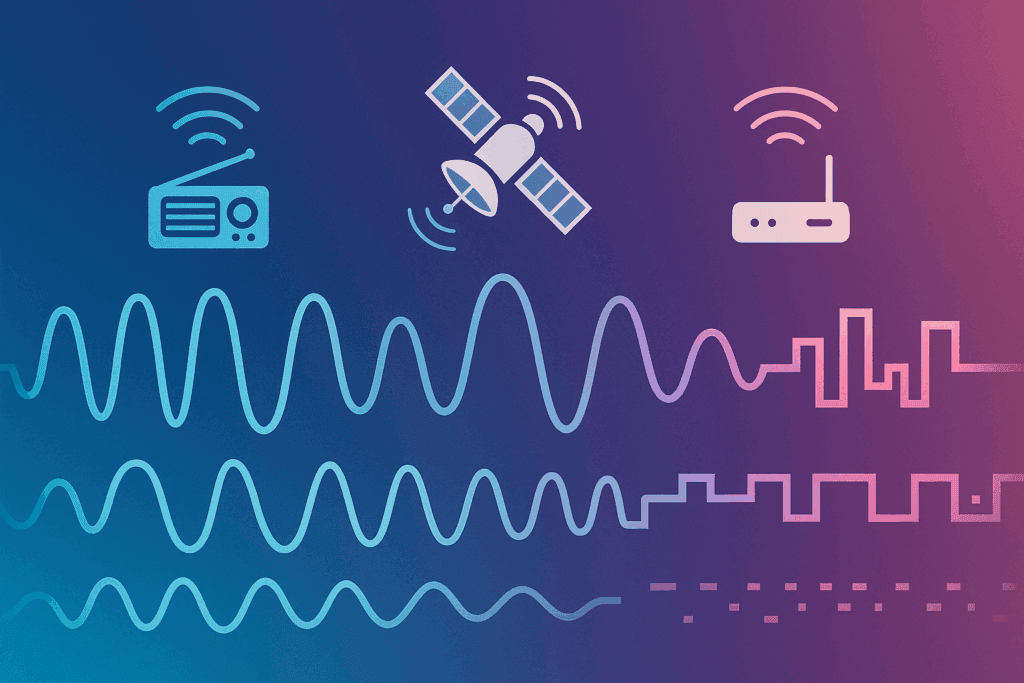

2.2 Encoding Information: Modulation

To convey data via electromagnetic waves, signals must be modulated—that is, altered in a way that represents information. The three primary modulation techniques are:

- Amplitude Modulation (AM) – changes the height of the wave

- Frequency Modulation (FM) – alters the frequency of the wave

- Phase Modulation (PM) – shifts the phase of the wave

Modern digital communication often uses combinations of these, such as Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (QAM) and Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing (OFDM).

2.3 Key Concepts in Wireless Communication

| Concept | Description |

| Frequency | The number of wave cycles per second (measured in Hertz, Hz) |

| Bandwidth | The range of frequencies available for transmission (Hz) |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | The strength of the signal relative to background noise |

| Latency | The time it takes for a signal to travel from sender to receiver |

| Range | The effective distance a signal can travel with usable strength |

| Interference | The disruption of signal clarity by other signals in the same frequency band |

| Propagation | How waves travel, reflect, refract, or are absorbed in different environments |

2.4 Infrastructure Elements

All wireless systems involve a set of common components:

- Transmitter: Encodes and emits the signal

- Receiver: Captures and decodes the signal

- Antenna: Converts electrical signals to and from electromagnetic waves

- Medium: The space (air, vacuum, water) through which the signal travels

Each wireless technology—radio, satellite, and Wi-Fi—implements these elements differently, optimizing for specific goals such as long-range coverage, high-speed data transfer, or low-power local networking.

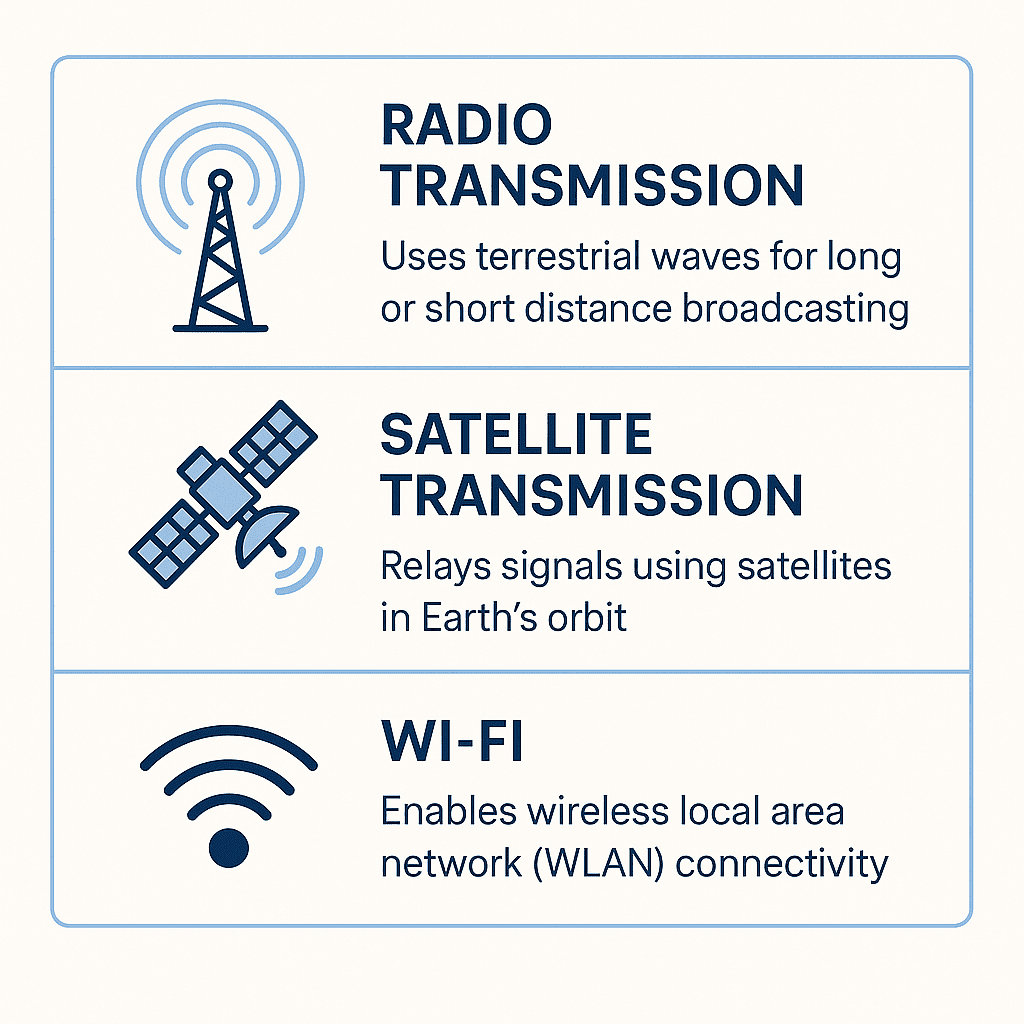

3. Radio Transmission

Radio communication is one of the oldest and most enduring forms of wireless transmission. It uses low- to mid-frequency electromagnetic waves to carry information such as voice, music, Morse code, and digital data across varying distances—from a few meters to thousands of kilometers. Radio technology forms the foundation for many wireless systems, including television, emergency communication, aviation, and maritime navigation.

3.1 History and Development

Radio transmission began in the late 19th century, with foundational work by James Clerk Maxwell (theoretical prediction of electromagnetic waves) and Heinrich Hertz (experimental validation). Guglielmo Marconi later built the first practical wireless telegraphy systems in the 1890s, leading to the widespread use of radio during World War I and in commercial broadcasting by the 1920s.

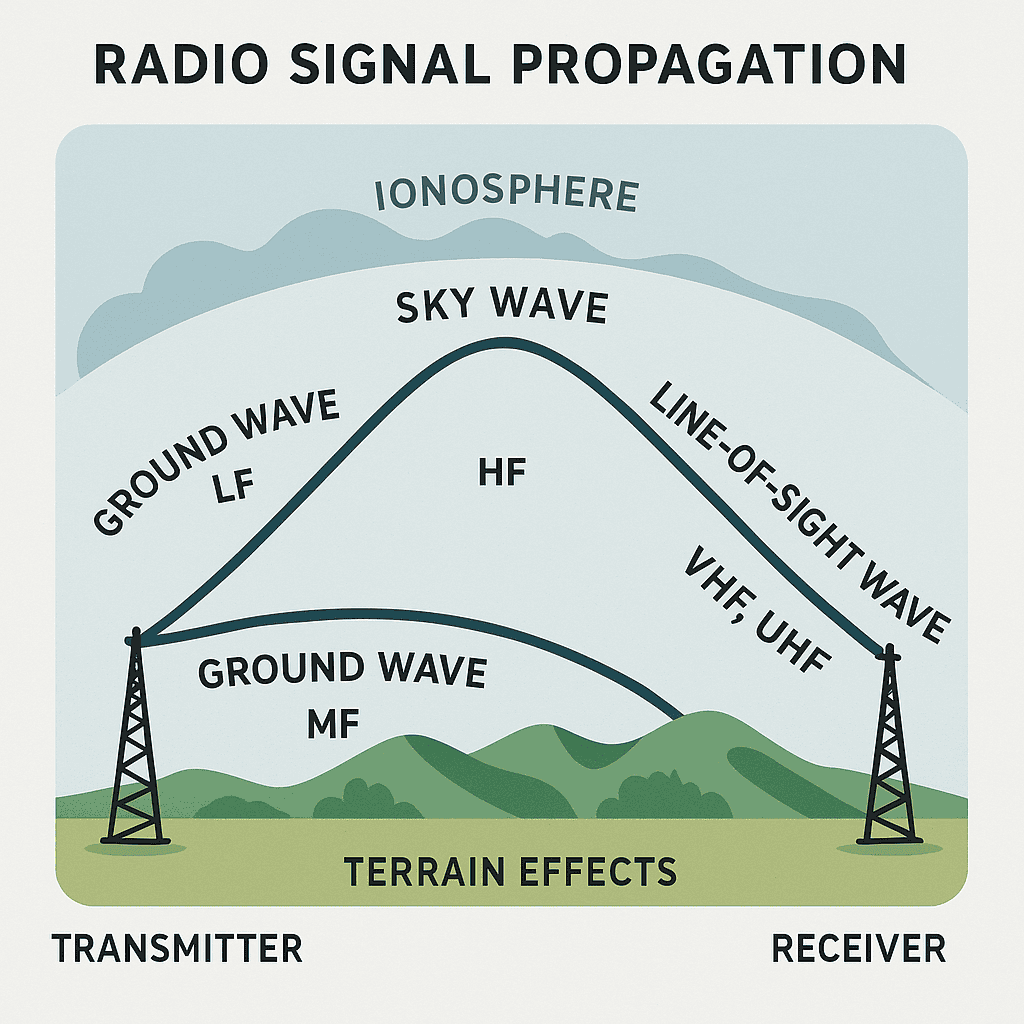

3.2 How It Works

Radio systems involve:

- A transmitter, which encodes information onto a carrier wave using modulation.

- An antenna, which radiates the modulated wave into the air.

- A receiver, which captures the wave, demodulates it, and converts it back into usable information (audio, digital signals, etc.).

Two main analog modulation types:

- AM (Amplitude Modulation): Information varies the amplitude of the carrier wave. Used in long-range radio broadcasts, especially AM bands (530–1700 kHz).

- FM (Frequency Modulation): Information varies the frequency of the wave. Offers better sound quality and noise resistance; used in FM radio (88–108 MHz).

Digital radio (e.g., DAB, DRM) now also exists, using digital signals modulated on radio frequencies for higher fidelity and compression efficiency.

3.3 Frequency Ranges and Applications

| Band Name | Frequency Range | Common Applications |

| LF (Low Frequency) | 30–300 kHz | Maritime navigation, submarine comms |

| MF (Medium Frequency) | 300–3000 kHz | AM radio |

| HF (High Frequency) | 3–30 MHz | Shortwave radio, long-distance comms |

| VHF (Very High Frequency) | 30–300 MHz | FM radio, aviation, TV broadcasts |

| UHF (Ultra High Frequency) | 300–3000 MHz | TV, GPS, mobile phones, two-way radios |

3.4 Strengths and Limitations

| Advantages | Limitations |

| Simple and cost-effective infrastructure | Limited bandwidth and data rates |

| Long-distance propagation (especially HF via ionosphere) | Susceptible to interference and noise (especially AM) |

| Can operate in remote or mobile conditions | Spectrum is congested; requires careful regulation and licensing |

| Resilient and widely supported | Analog signals degrade with distance and obstacles |

Radio technology remains foundational in critical sectors—aviation, emergency services, public broadcasting, and amateur (ham) radio—thanks to its simplicity, resilience, and adaptability.

4. Satellite Transmission

Satellite communication enables wireless data exchange over vast distances by relaying signals between ground stations via orbiting satellites. It provides global coverage, essential for applications where traditional terrestrial infrastructure is impractical—such as oceanic communication, remote internet access, global navigation, and weather monitoring.

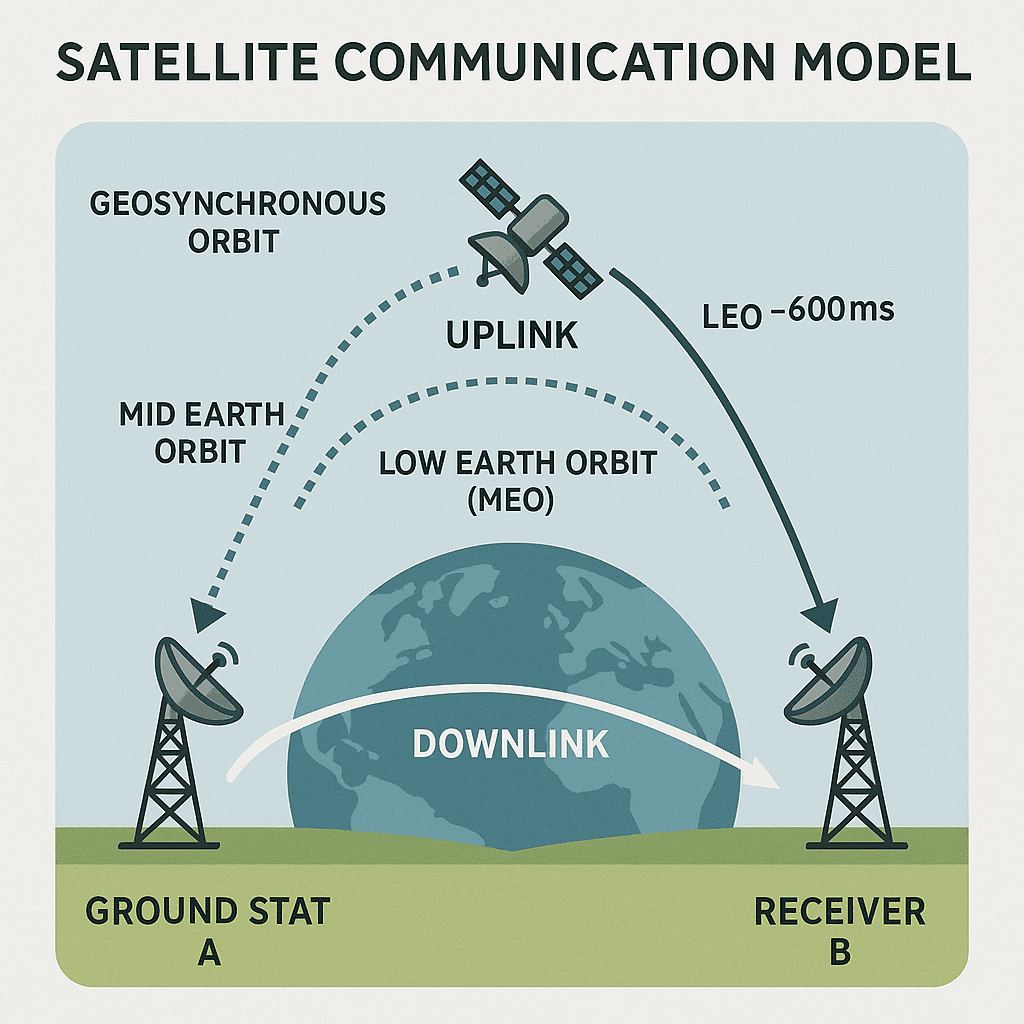

4.1 Introduction to Satellite Communication

Satellite transmission involves sending a signal from an Earth-based transmitter (uplink) to a satellite, which then relays it back to another ground location (downlink). Depending on the satellite’s orbit, this can enable near-instantaneous communication between two points on opposite sides of the Earth.

This technology is crucial for:

- Global telephony and broadcasting

- GPS and navigation

- Remote sensing

- Space exploration and interplanetary communication

4.2 How It Works

The basic components include:

- Ground stations (Earth terminals): Send and receive signals to/from space

- Uplink: Signal transmitted from Earth to satellite

- Satellite transponder: Receives, amplifies, processes, and retransmits signals

- Downlink: Signal transmitted from satellite to a different Earth location

Satellites typically use microwave frequencies in bands such as:

- L-band (1–2 GHz): GPS, mobile satellite services

- C-band (4–8 GHz): Long-range communication

- Ku-band (12–18 GHz): Broadcasting and internet

- Ka-band (26–40 GHz): High-bandwidth data services

Advanced systems may use beamforming and frequency reuse to optimize performance.

4.3 Types of Satellites by Orbit

| Orbit Type | Altitude | Latency | Coverage | Examples |

| LEO (Low Earth Orbit) | ~200–2,000 km | Very low (10–50 ms) | Small region, high resolution | Starlink, Earth observation |

| MEO (Medium Earth Orbit) | ~2,000–20,000 km | Moderate (~70–100 ms) | Regional/global | GPS constellation |

| GEO (Geostationary Orbit) | ~35,786 km | High (~250–600 ms) | Full Earth hemisphere | Weather, TV broadcasting (e.g. GOES, Intelsat) |

4.4 Coverage, Delay, and Cost Considerations

| Parameter | Satellite Communication |

| Coverage | Global, especially from GEO; polar coverage via LEO |

| Latency | Significant in GEO (~600 ms); much lower in LEO |

| Bandwidth | Increasing with Ka-band; congestion possible |

| Infrastructure Cost | High initial cost (satellite launch, ground stations) |

| Scalability | High; mesh and swarm satellites can expand services |

| Weather Sensitivity | Ka-band and above affected by rain fade |

Despite its latency and infrastructure costs, satellite transmission offers unmatched reach and reliability, particularly for maritime, rural, military, and space-based applications. With the rise of LEO mega-constellations like SpaceX’s Starlink and Amazon’s Project Kuiper, low-latency satellite internet is becoming increasingly feasible for everyday consumers.

5. Wi-Fi (Wireless Fidelity)

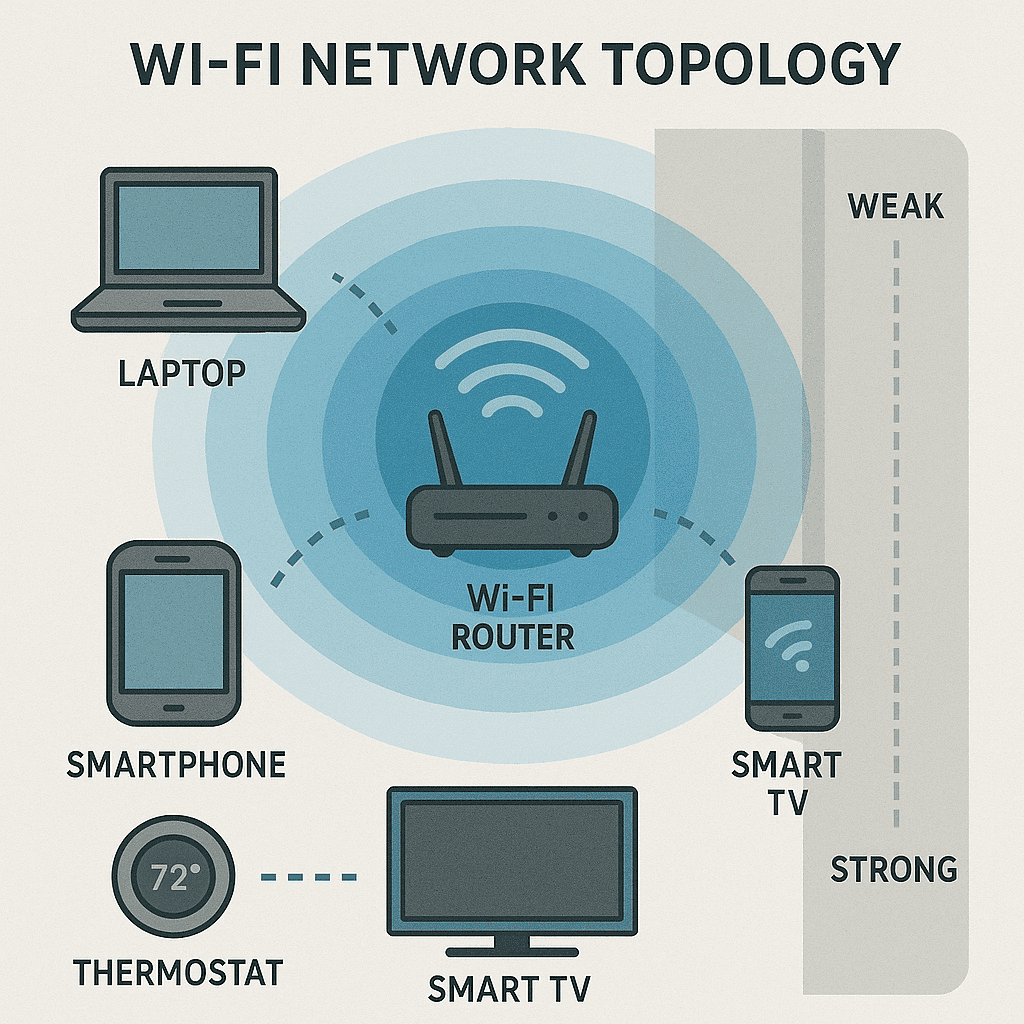

Wi-Fi is a form of wireless local area networking (WLAN) that enables devices to connect to the internet or each other through a central access point, typically a router. Unlike radio and satellite communication, which are designed for wide-area or global coverage, Wi-Fi is optimized for short-range, high-speed communication in homes, offices, schools, and public spaces.

5.1 Basics of Wi-Fi Technology

Wi-Fi operates under the IEEE 802.11 standards, which define how wireless devices communicate using radio frequencies. It enables seamless data exchange between smartphones, laptops, smart appliances, printers, and more. The key advantage of Wi-Fi is that it eliminates the need for wired Ethernet connections while delivering broadband-level performance.

5.2 How It Works

Wi-Fi involves the following core components:

- Wireless Router or Access Point (AP): Acts as a hub that broadcasts a wireless signal and connects to the internet.

- Client Devices: Laptops, smartphones, IoT devices that connect to the access point using wireless adapters.

- Modulation: Typically uses OFDM (Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing) and QAM (Quadrature Amplitude Modulation) for high-speed, interference-resistant transmission.

Wi-Fi systems use Carrier Sense Multiple Access with Collision Avoidance (CSMA/CA) to manage shared access to the frequency band and prevent signal collisions.

5.3 Frequency Bands

Wi-Fi primarily operates in three unlicensed frequency bands:

- 2.4 GHz: Longer range, more interference (shared with microwaves, Bluetooth)

- 5 GHz: Shorter range, higher speeds, less interference

- 6 GHz (Wi-Fi 6E): Newer, cleaner spectrum with high capacity and very low latency

| Band | Pros | Cons |

| 2.4 GHz | Long range, better wall penetration | Congested, slower speeds |

| 5 GHz | Faster speeds, less interference | Reduced range, limited wall penetration |

| 6 GHz | Ultra-fast speeds, low latency, many channels | Requires newer hardware, limited range |

5.4 Wi-Fi Standards and Evolution

| Standard | Max Speed | Frequency Band | Key Feature |

| 802.11b | 11 Mbps | 2.4 GHz | First mass adoption |

| 802.11g | 54 Mbps | 2.4 GHz | Faster, backward compatible |

| 802.11n (Wi-Fi 4) | 600 Mbps | 2.4/5 GHz | MIMO (multiple antennas) |

| 802.11ac (Wi-Fi 5) | 1.3 Gbps | 5 GHz | Beamforming, more channels |

| 802.11ax (Wi-Fi 6/6E) | 9.6 Gbps | 2.4/5/6 GHz | OFDMA, low latency, dense environments |

| 802.11be (Wi-Fi 7) | ~30 Gbps (projected) | 6 GHz | Multi-link operation, ultra-low latency |

5.5 Strengths and Limitations

| Advantages | Limitations |

| High-speed, high-bandwidth | Short range, especially at higher frequencies |

| Easy to deploy and expand | Performance drops with distance and interference |

| Cost-effective and widely supported | Security vulnerabilities (unless properly encrypted) |

| Supports large numbers of devices in small areas | Congestion in high-density or urban areas |

Wi-Fi has become the ubiquitous wireless technology for local connectivity, powering everything from entertainment streaming to smart home automation. Its constant evolution continues to raise performance benchmarks for local-area wireless communication.

6. Comparative Analysis Table

To clearly distinguish the characteristics, performance, and typical use cases of radio, satellite, and Wi-Fi technologies, the following comparative table summarizes key technical and operational parameters:

6.1 Technology Comparison Table

| Parameter | Radio Transmission | Satellite Transmission | Wi-Fi (Wireless Fidelity) |

| Frequency Range | 30 kHz – 3 GHz | 1 GHz – 40 GHz (L, C, Ku, Ka bands) | 2.4 GHz, 5 GHz, 6 GHz |

| Range | Local to global (varies by band and power) | Global (GEO), regional (MEO), local-to-global (LEO) | Typically 10–50 meters indoors |

| Bandwidth | Narrow (AM/FM), wider for digital and UHF/VHF | High, especially with Ka-band | Very high (up to 9.6 Gbps with Wi-Fi 6) |

| Data Rate | Low to moderate | Moderate to high, improving with LEO constellations | High to very high |

| Latency | Very low | High (GEO ~600 ms), Moderate (MEO), Low (LEO ~20–40 ms) | Very low (~1–20 ms) |

| Mobility | High (used in vehicles, ships, aircraft) | High (mobile users supported via ground-to-satellite links) | Low to moderate (primarily stationary or local) |

| Power Requirement | Low to moderate | High (both satellite and ground terminals) | Low (routers and devices operate on mains or battery) |

| Infrastructure Cost | Low (especially for broadcast radio) | Very high (satellite design, launch, maintenance) | Low to moderate (consumer-grade access points) |

| Deployment Time | Quick (esp. portable radios) | Long (planning, launch, coordination with ground network) | Short (plug-and-play in consumer settings) |

| Resilience | High (robust under difficult conditions) | High (space-based systems are hard to disrupt) | Medium (signal easily disrupted by walls/interference) |

| Applications | AM/FM, emergency comms, aviation, marine, ham radio | Internet, TV, GPS, weather, global comms | Local networks, home internet, smart devices, IoT |

6.2 Summary of Suitability

| Use Case | Best Technology |

| Broadcasting over large distances | Radio Transmission |

| Global internet access | Satellite (LEO/MEO) |

| Emergency communication | Radio (VHF/UHF) |

| GPS navigation | Satellite (MEO) |

| Local high-speed internet | Wi-Fi |

| Remote area connectivity | Satellite (GEO/LEO) |

| Smart homes and IoT environments | Wi-Fi |

| In-flight or shipboard communication | Satellite + Radio Hybrid |

This comparison clarifies that while all three technologies transmit data wirelessly, they are optimized for different scales, ranges, and conditions. Rather than competing directly, they often complement each other in integrated communication networks.

7. Applications and Use Cases

Each of the three wireless technologies—radio, satellite, and Wi-Fi—serves distinct roles in the global communication ecosystem. Their unique properties make them ideal for different physical scales, environments, and purposes.

7.1 Radio: Broadcasting and Emergency Communication

Primary Functions:

- Broadcast media: AM/FM radio remains a primary tool for public audio broadcasting, especially in cars and rural areas.

- Public safety: Police, fire, and rescue units rely on VHF/UHF radios for quick, reliable coordination.

- Amateur radio (ham radio): Provides a resilient and decentralized backup communication network in disasters.

- Aviation and marine: Used for air traffic control, cockpit communication, and marine navigation (VHF band).

Advantages in Use:

- Resilient in harsh environments

- Operates independently of internet infrastructure

- Easily received by inexpensive devices

7.2 Satellite: Remote Access and Global Services

Primary Functions:

- Internet and telephony in remote regions: Rural villages, oil rigs, disaster zones

- Global Positioning System (GPS): Navigation for civilians, military, aviation, and logistics

- Weather monitoring: Real-time atmospheric data via satellites like GOES, Himawari

- Broadcasting and media distribution: Satellite TV and radio, global content delivery

- Space communications: Deep space probes, interplanetary data transfer (e.g., DSN)

Advantages in Use:

- Covers areas unreachable by terrestrial means

- Crucial for mobile platforms: ships, airplanes, vehicles

- Central to global infrastructure (timing, mapping, surveillance)

7.3 Wi-Fi: Personal, Domestic, and Enterprise Connectivity

Primary Functions:

- Home and office networking: High-speed internet access for computers, phones, and tablets

- Public hotspots: Cafes, airports, libraries, hotels

- Enterprise and education: Enables productivity tools, collaborative learning, and digital classrooms

- Smart homes and IoT: Controls smart appliances, sensors, cameras, and thermostats

- Media streaming and gaming: Supports high-bandwidth video and low-latency gameplay

Advantages in Use:

- High throughput in short range

- Easy setup and low infrastructure cost

- Scalable for dense device environments (with modern standards like Wi-Fi 6)

These applications illustrate how each technology serves specific communication needs—from broadcasting a city-wide alert to live-streaming a movie to navigating a delivery drone. They are not interchangeable, but rather, complementary components in an interlinked wireless ecosystem.

8. Future Trends in Wireless Communication

As our global reliance on wireless connectivity intensifies, all three technologies—radio, satellite, and Wi-Fi—are undergoing rapid transformation. Driven by the demand for higher data speeds, lower latency, greater coverage, and more energy efficiency, the future of wireless communication lies in integration, innovation, and intelligent automation.

8.1 5G, 6G, and Satellite Integration

The rollout of 5G networks is already revolutionizing mobile and industrial connectivity through:

- Ultra-low latency (1–10 ms)

- High speeds (up to 10 Gbps)

- Network slicing for customized service delivery

Next-generation 6G (projected by 2030) aims to incorporate:

- Terahertz frequencies for ultra-high data rates

- Satellite-augmented mobile networks, including space-based 5G cells

- Integrated AI for adaptive signal optimization

Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellite networks like Starlink, OneWeb, and Project Kuiper are being designed to complement terrestrial 5G, offering near-global low-latency coverage—even in remote or mobile environments like aircraft and ships.

8.2 Wi-Fi 7 and Beyond

Wi-Fi 7 (IEEE 802.11be) is the next major leap in WLAN technology, expected to feature:

- Throughput exceeding 30 Gbps

- Multi-link operation across different bands simultaneously

- Lower latency for real-time applications (e.g., VR/AR, cloud gaming)

- Enhanced Quality of Service (QoS) and congestion management

Beyond Wi-Fi 7, researchers are exploring Li-Fi (light-based wireless networking), UWB (ultra-wideband), and mesh Wi-Fi architectures to support dynamic smart environments and device interoperability.

8.3 Internet of Things (IoT) and Smart Ecosystems

The proliferation of IoT devices—sensors, wearables, vehicles, appliances—demands new wireless strategies:

- Low-power protocols (e.g., Zigbee, LoRaWAN) for long battery life

- Edge computing to reduce reliance on centralized data centers

- Wi-Fi 6/7 and private 5G networks to support dense device clusters

Radio technology is also being adapted for low-bandwidth IoT applications, such as LPWAN (Low-Power Wide-Area Networks), ideal for agriculture, asset tracking, and environmental monitoring.

8.4 AI, Quantum, and Ambient Intelligence

Emerging frontiers include:

- AI-optimized wireless systems that dynamically adjust spectrum use, avoid interference, and allocate bandwidth intelligently

- Quantum communication for secure satellite links using entangled photon pairs

- Ambient backscatter and energy harvesting networks—enabling devices to transmit data using reflected signals and minimal power

These technologies are set to blur the lines between infrastructure and intelligence, embedding communication into the environment itself.

In summary, the future of wireless communication is multi-layered, decentralized, and adaptive. Radio will remain vital for resilient and long-range needs. Satellite will grow more essential for planetary coverage and mobility. Wi-Fi will continue evolving as the invisible backbone of digital life. Together, they form a hybrid global network—smart, seamless, and increasingly indispensable.

9. Conclusion – A Spectrum of Solutions

In a world knit together by invisible signals, wireless communication technologies serve as the nervous system of civilization. Radio, satellite, and Wi-Fi—though often taken for granted—form a triad of complementary systems that support everything from emergency response to home entertainment, from interplanetary science to everyday conversation.

Each operates in its own range of the electromagnetic spectrum, with unique strengths and trade-offs:

- Radio remains the cornerstone of resilient, long-range, and low-bandwidth communication—essential in broadcasting, transportation, and emergency services.

- Satellite transmission extends our reach beyond borders, oceans, and even Earth itself, enabling truly global and extraterrestrial communication.

- Wi-Fi empowers dense, high-speed, localized networking—fueling our homes, schools, workplaces, and increasingly, our cities and personal devices.

These technologies are not competitors, but rather parts of a layered, integrated network ecosystem, each optimized for a different context. As we move toward a hyper-connected future, the convergence of wireless systems—with AI orchestration, satellite augmentation, and smart spectrum sharing—will define the next era of communication.

Understanding how these systems work, where they excel, and how they evolve is not only a matter of technical literacy—it is a foundational insight for navigating and shaping the digital world of the 21st century and beyond.