Table of Contents

I. Introduction: A Contemplative Visualization of Cosmic Genesis

- The Big Bang and the birth of the universe

- Formation of galaxies, stars, and solar systems

- The Earth emerges: a unique cradle of life

II. Timeline of Evolutionary Landmarks

- Visual and textual chronological chart

- From the birth of the Earth to the emergence of multicellular life

III. The Birth of Life: From Chemistry to Biology

- Conditions on early Earth

- Scientific discoveries on how the first cells formed (Phys.org 2024)

- Formation of protocells and primitive membranes

IV. LUCA: The Last Universal Common Ancestor

- What LUCA is and why it matters

- Hypothesized traits of LUCA

- The branching of life into Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya

V. The First Microbial Life Forms

- Microbes and microbial mats

- Stromatolites: fossilized microbial life

- Evidence from graphite in zircons, Apex chert, Isua Belt, and Pilbara Craton

VI. The Rise of Photosynthesis and Oxygenation of Earth

- Cyanobacteria and the Great Oxidation Event

- Transition from anaerobic to aerobic life

VII. The First Plants on Earth

- Early algae and non-vascular plants

- Colonization of land: mosses, liverworts, hornworts

VIII. The First Animals on Earth

- The Ediacaran fauna

- Sponges and early soft-bodied creatures

- Insights from fossil records (Oxford University Museum of Natural History)

IX. The First Mobile Life Forms

- Gabon fossils and early movement

- Implications for early ecosystems and behavior

X. The Earliest Biomes and Ecological Networks

- Oceanic microbial biomes

- Hydrothermal vents, shallow seas, and tidal zones

- Early terrestrial biomes and microbial crusts

XI. Toward Complexity: Prelude to Dinosaurs

- Cambrian explosion (brief mention)

- Evolution of vertebrates, plants, insects

- Lead-in to next article on dinosaurs and prehistoric Earth

XII. Conclusion: The Fragile Miracle of Living Earth

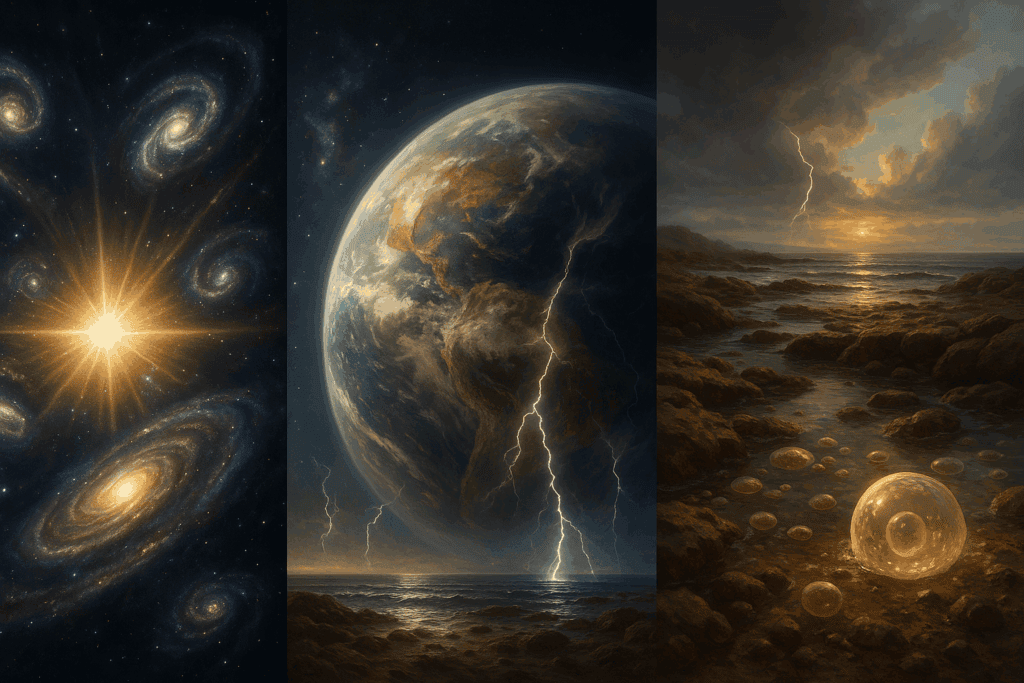

I. A Contemplative Visualization of Cosmic Genesis

From Nothingness to the Living Earth

In the beginning, there was no time, no space, no matter—only a singularity, dense beyond comprehension, silent and absolute. Then, in a moment beyond imagination, the Big Bang ruptured the void. From this primeval fireball unfurled the fabric of time and space. It was not an explosion in space—it was the expansion of space itself.

As the universe cooled, energy crystallized into matter, forming the simplest particles: quarks and electrons. These coalesced into protons and neutrons, which in turn gave rise to the first atoms—hydrogen and helium—bathed in a radiant sea of cosmic light. Gravity began its slow, eternal pull, gathering matter into clouds that swirled and collapsed to form the first stars.

These stellar furnaces lived and died, forging the elements in their cores—carbon, oxygen, iron—only to scatter them in magnificent supernovae. In this cycle of creation and destruction, the chemical ingredients of life were born. Galaxies spun into shape. One such spiral arm, among billions, hosted a modest star: our Sun. Around it, dust and gas gave birth to rocky planets and icy moons.

Among these was Earth, formed about 4.54 billion years ago—a molten sphere battered by comets, meteorites, and solar wind. Over time, its surface cooled. Rain fell on steaming crust. Oceans gathered in basins. The skies thickened with gases. Lightning flashed. Volcanoes roared. And in the cauldron of this young, tempestuous world, the stage was set for the most astonishing transformation of all: the rise of life.

As we contemplate this grand unfolding—from cosmic singularity to blue planet—it is humbling to recall that the atoms in our bodies were once part of stars. Life is not an anomaly within the universe. It is a chapter in the story of the cosmos itself, written in hydrogen, oxygen, and carbon. And Earth, cradled in a quiet corner of a galaxy, became the setting for the emergence of self-organizing complexity, and eventually, consciousness itself.

The journey of life began in the depths of this planetary ocean—not with creatures, but with molecules that danced, combined, split, and began to remember. From those silent beginnings would arise the full drama of evolution.

II. Timeline of Evolutionary Landmarks

Below is a chronological summary of the major epochs and turning points in the origin and evolution of life on Earth. Each entry marks a foundational moment in the long and wondrous journey from primordial chemistry to the complex web of life we know today.

13.8 Billion Years Ago – The Big Bang

The universe begins. Space, time, energy, and matter emerge from a singularity. Hydrogen and helium dominate, forming the first stars and galaxies.

4.6 Billion Years Ago – Formation of the Solar System

Our Sun and planets form from a collapsing molecular cloud. Earth coalesces as a molten planet.

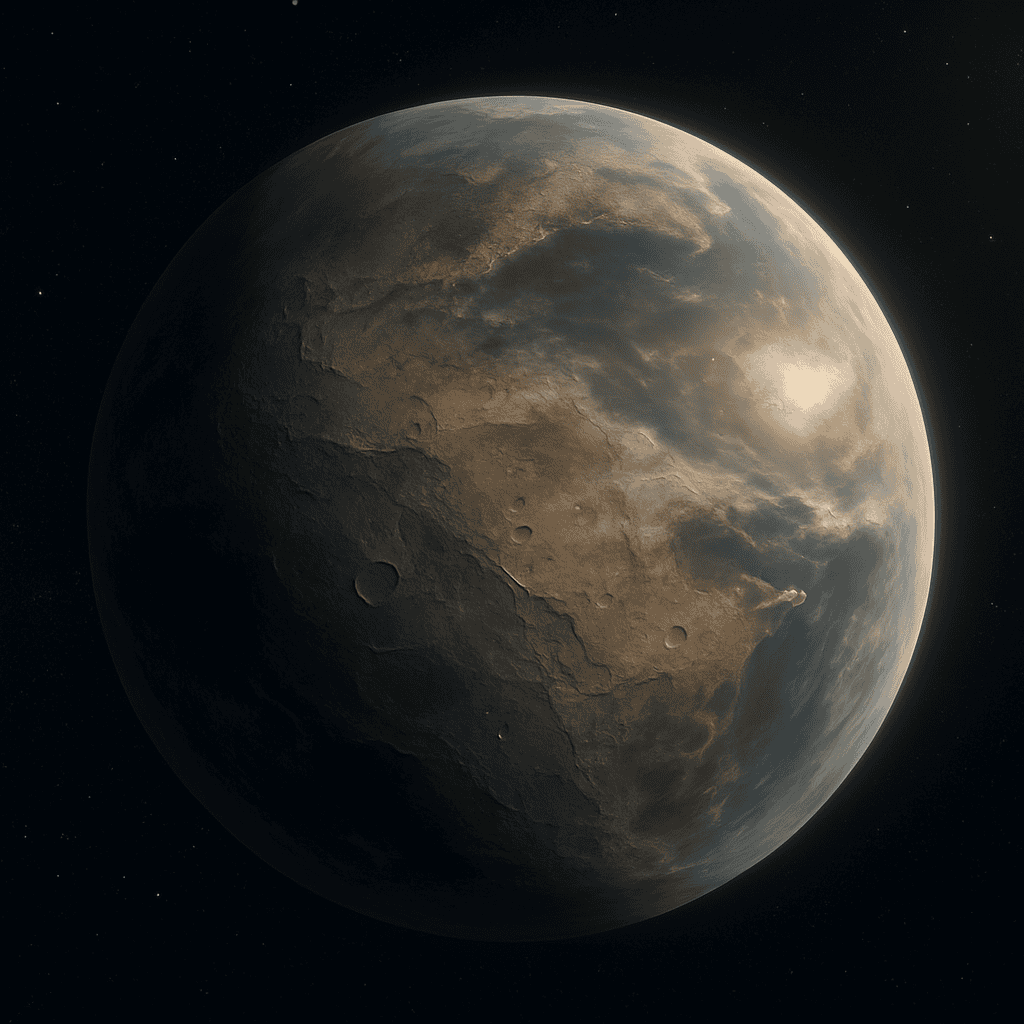

4.54 Billion Years Ago – Formation of Earth

The early Earth forms. Its surface gradually cools, forming a solid crust and vast oceans. Conditions emerge that may support life.

4.4–4.1 Billion Years Ago – Water and Prebiotic Chemistry

Liquid water becomes stable. Organic molecules form in Earth’s oceans, powered by geothermal vents, lightning, and UV radiation.

4.1–3.8 Billion Years Ago – First Evidence of Life (Possibly)

Biologically fractionated carbon in ancient zircon grains from Australia suggests life may have existed as early as 4.1 billion years ago.

3.7–3.5 Billion Years Ago – Microbial Life and Stromatolites

The oldest confirmed fossils of microbial life appear in rocks from Greenland and Australia. Stromatolites—layered microbial mats—emerge.

2.4 Billion Years Ago – The Great Oxidation Event

Photosynthetic cyanobacteria release oxygen as a byproduct, altering Earth’s atmosphere and enabling aerobic life to evolve.

2.1 Billion Years Ago – First Mobile Multicellular Life

In Gabon, fossil evidence shows organisms capable of movement—tubular trackways suggest active, multicellular life.

1.7 Billion Years Ago – Rise of Eukaryotic Cells

Complex cells with nuclei and organelles evolve, possibly through symbiotic merging of simpler cells.

1.6–1.0 Billion Years Ago – First Algae and Early Plants

Green and red algae dominate oceans. Simple multicellular organisms pave the way for land plant evolution.

800–600 Million Years Ago – Animal Precursors and Ediacaran Biota

Soft-bodied multicellular organisms emerge in oceans. This prelude to the Cambrian explosion includes sponges and jelly-like creatures.

541 Million Years Ago – The Cambrian Explosion

Life diversifies rapidly in the oceans. Many major animal phyla appear. Hard shells, eyes, and predation arise.

500–400 Million Years Ago – Plants and Animals Conquer Land

Mosses, liverworts, and early vascular plants spread across land. Arthropods and the first vertebrates follow.

370–250 Million Years Ago – Tetrapods and the Age of Amphibians

Lobed-finned fish evolve into four-limbed land vertebrates. Swamps, insects, and early forests dominate.

250–65 Million Years Ago – Dinosaurs and Mesozoic Fauna

The Mesozoic Era begins. Dinosaurs evolve, dominate, and diversify alongside flowering plants and early mammals.

65 Million Years Ago – Mammalian Expansion

After the extinction of the dinosaurs, mammals diversify and evolve into many niches, eventually including primates.

2–0.2 Million Years Ago – Rise of Homo sapiens

Human ancestors emerge in Africa. By 200,000 years ago, anatomically modern humans appear—capable of language, culture, and science.

III. The Birth of Life: From Chemistry to Biology

The Spark Within the Primordial Sea

Beneath the heavy skies of the early Earth, some 4.1 to 3.8 billion years ago, our planet was a restless laboratory. Volcanoes spewed molten rock into shallow seas, lightning cracked through methane-rich air, and hydrothermal vents bubbled with mineral-rich heat from Earth’s deep interior. Amid this turbulent environment, non-living molecules began to organize themselves in novel, life-like ways.

This is the threshold where chemistry became biology.

Prebiotic Chemistry and the Ingredients of Life

The fundamental ingredients of life—carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur—were already present. Amino acids, nucleotides, and fatty acids could form under early Earth conditions, as famously demonstrated by the Miller-Urey experiment in the 1950s and refined by decades of newer models. These building blocks of proteins, RNA, and membranes likely accumulated in tidepools or near hydrothermal vents, where they interacted in cycles of evaporation, heat, and mineral catalysis.

In 2024, new research published on Phys.org illuminated how simple chemical networks may have led to the formation of protocells—microscopic bubbles with primitive membranes that could trap organic molecules inside. These protocells did not yet have DNA, but they exhibited features of metabolism, selectively interacting with their environment and, crucially, replicating imperfectly, allowing for variation and evolution.

The Role of Hydrothermal Vents

Deep beneath the ocean, alkaline hydrothermal vents may have provided the perfect environment for life’s emergence. Here, warm, mineral-rich water flowed through porous rock, creating natural compartments with energy gradients. These miniature chambers acted like primitive batteries and incubators—supporting the concentration and transformation of molecules into early metabolic cycles.

The structure of modern cellular enzymes and genetic systems appears to retain echoes of this origin, suggesting that the first “living systems” were not isolated individuals, but networks of chemistry embedded in rock, which gradually gave rise to independent, free-floating cells.

From Protocells to True Cells

At some point, a breakthrough occurred: RNA or similar self-replicating molecules began to carry information from one generation to the next. Encased in lipid membranes and driven by rudimentary metabolisms, these structures became the first true cells—not yet complex, but alive by all scientific definitions.

These earliest forms of life were anaerobic (thriving without oxygen), and consumed simple organic compounds from their environment. They multiplied, mutated, and evolved, adapting to conditions and eventually giving rise to diverse descendants.

Thus, life did not begin with a bang, but with a whisper—molecules dancing in warm water, gradually becoming something more. From a lifeless Earth, something began to self-organize, to replicate, to persist. In the simplicity of those first cells lay the seed of all future complexity: forests, whales, brains, civilizations.

IV. LUCA – The Last Universal Common Ancestor

The Root from Which All Life Descended

As life diversified from its primordial origins, one lineage emerged that would ultimately give rise to every known organism on Earth. Scientists call this hypothetical ancestor LUCA—the Last Universal Common Ancestor. LUCA is not the first life form, but rather the most recent common node in the family tree of all current life, predating the split into the three great domains: Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya.

What Was LUCA?

LUCA was not a single, miraculous organism, but likely a population of early cells sharing genes through horizontal gene transfer in the chaotic early biosphere. These organisms lived more than 3.5 to 4 billion years ago, thriving in anaerobic conditions, possibly near deep-sea hydrothermal vents, where temperature gradients, minerals, and chemical energy provided a nurturing niche.

While no fossil of LUCA has been found (and likely never will), genomic analysis allows scientists to infer some of LUCA’s probable characteristics by comparing genes shared across all domains of life.

Likely Features of LUCA

LUCA is thought to have had:

- A cell membrane enclosing its contents

- A genetic code made of RNA and/or DNA

- Ribosomes for translating RNA into proteins

- Basic metabolic pathways, including fermentation or chemosynthesis

- Enzymes that used ATP for energy

- Dependency on metal ions like iron, magnesium, and zinc

- Absence of oxygen metabolism (it was likely anaerobic)

These features form the molecular signature that links every living organism, from bacteria in the soil to the neurons in the human brain.

LUCA and the Tree of Life

Life soon branched into three major domains:

- Bacteria: single-celled organisms with simple internal structure

- Archaea: similar in form to bacteria but genetically distinct, often found in extreme environments

- Eukarya: more complex cells with nuclei, which eventually gave rise to plants, fungi, animals, and humans

LUCA sat at the root of this tripartite divergence, linking all of biology in a single shared origin. The discovery that Archaea and Eukarya are more closely related to each other than to Bacteria has reshaped our understanding of evolutionary history, showing that life’s deepest split was not between “simple” and “complex”, but among diverse strategies for surviving on an ever-changing planet.

A Shared Ancestry Across Billions of Years

Though we differ in form, function, and intelligence, every organism on Earth is a cousin—a relative by descent from LUCA. The genes that encode the machinery of life, from the polymerase that copies DNA to the ATP synthase that powers cells, are ancient legacies inherited from this universal ancestor.

In LUCA, we glimpse the deep unity of life, a thread that binds all beings across space, time, and species. From its microscopic body unfolded the entire biosphere, branching over billions of years into trilobites and trees, jellyfish and jaguars, orchids and orchestras.

V. The First Microbial Life Forms

Life’s Ancient Architects

Long before animals roamed the land or plants greened the continents, Earth belonged entirely to microbes. These ancient, single-celled organisms—prokaryotes without nuclei—were the first living beings to leave their mark on the planet. Emerging at least 3.7 billion years ago, and possibly as early as 4.1 billion years ago, microbes were not only the origin of life but also the primary force shaping Earth’s atmosphere, oceans, and geology for billions of years.

The Earliest Signs of Life

The oldest indirect evidence of life comes from graphite inclusions in zircon crystals dated to 4.1 billion years ago, found in the Jack Hills of Australia. The carbon isotopic signature in these minerals suggests biological activity—an astonishingly early date, not long after Earth had cooled enough for oceans to form.

More direct evidence appears in:

- 3.7 Ga (billion years ago) rocks from the Isua Supracrustal Belt in Greenland, containing biologically derived carbon in metasedimentary formations.

- 3.48 Ga stromatolite fossils in the Dresser Formation of the Pilbara Craton in Western Australia, formed by microbial mats.

- 3.465 Ga Apex chert microfossils, interpreted as filamentous bacteria, also from the Pilbara region.

- 3.42 Ga hydrothermal vent deposits from Barberton, South Africa, with microfossils embedded in silica precipitates.

These findings suggest that life emerged quickly once Earth’s environment became stable enough to support it—an indication that life, given the right conditions, may be a natural outcome of planetary evolution.

Stromatolites: Earth’s Living Fossils

Among the most compelling and enduring traces of early life are stromatolites—layered rock formations built by microbial communities, particularly cyanobacteria. These organisms trap and bind sediment, leaving behind distinct laminar structures that fossilize over time.

- Stromatolites are the earliest direct macrofossils of life, some dating back 3.5 billion years.

- Modern stromatolites still exist today in hypersaline environments like Shark Bay, Australia—offering a glimpse into the ancient microbial world.

These living fossils show how microbes were not passive residents of early Earth, but dynamic ecosystem engineers, altering the chemical and geological landscape in profound ways.

Masters of Metabolism

Early microbial life was diverse in its survival strategies. Many of the first organisms likely:

- Fermented organic molecules for energy.

- Used chemosynthesis, deriving energy from sulfur or iron compounds in hydrothermal vents.

- Eventually evolved photosynthesis—particularly oxygenic photosynthesis in cyanobacteria, which released free oxygen into the atmosphere.

This last innovation would change the course of planetary history during the Great Oxidation Event (~2.4 billion years ago), paving the way for aerobic respiration and, much later, complex multicellular life.

Unseen, But Ubiquitous

Even today, microbes dominate life on Earth in terms of biomass, diversity, and ecological importance. They inhabit every environment—from the deep subsurface to the high atmosphere, from boiling acid pools to the human gut.

They are not our ancestors alone; they are our continuing kin.

From these ancient cells—flickering into being in a sunlit sea—arose all the biodiversity that has ever existed. The humble microbe is both origin and omnipresence: the silent architect of all subsequent life.

VI. The Rise of Photosynthesis and the Oxygenation of Earth

How Microbes Transformed the Atmosphere and Enabled Complex Life

Among the most pivotal events in the history of life—and of Earth itself—was the rise of photosynthesis: the ability to capture sunlight and convert it into chemical energy. This innovation, developed by ancient microbes, did not just fuel life; it transformed the planet, turning a suffocating, anoxic world into one filled with breathable air and setting the stage for all future complex organisms.

Ancestral Phototrophs and the Power of Light

The earliest photosynthetic microbes likely emerged around 3.5 billion years ago. These primitive organisms harnessed light to drive chemical reactions, but they did not release oxygen. Instead, they used molecules like hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) or ferrous iron (Fe²⁺) as electron donors. These anoxygenic phototrophs were precursors to one of Earth’s most revolutionary lineages: the cyanobacteria.

Cyanobacteria and Oxygenic Photosynthesis

Around 2.7 to 2.4 billion years ago, cyanobacteria evolved the ability to split water (H₂O) molecules during photosynthesis, releasing oxygen (O₂) as a byproduct. This process, known as oxygenic photosynthesis, is the same one still performed by plants and algae today.

Cyanobacteria formed dense microbial mats in shallow seas and tidal flats. Their abundant oxygen production slowly accumulated in the atmosphere and oceans, though at first, this oxygen reacted with dissolved iron and volcanic gases, preventing atmospheric buildup.

The Great Oxidation Event (~2.4 Billion Years Ago)

Eventually, around 2.4 Ga, Earth’s chemical sinks became saturated, and oxygen began to accumulate in the atmosphere—a turning point known as the Great Oxidation Event (GOE).

Consequences of the GOE were profound:

- Massive extinctions of anaerobic life forms, for whom oxygen was toxic

- Formation of banded iron formations (BIFs) in marine sediments

- Rise of an ozone layer, shielding Earth’s surface from harmful ultraviolet radiation

- Expansion of aerobic respiration, a more energy-efficient metabolic pathway

Oxygen enabled organisms to extract far more energy from organic compounds, which made larger and more complex life possible.

The Long Oxygenation Process

Although the GOE was a dramatic shift, oxygen levels rose slowly and unevenly for the next 2 billion years. Oceans remained largely anoxic and sulfidic in many regions, forming “oxygen oases” near microbial mats while deep waters stayed inhospitable to most life.

It wasn’t until around 800 to 600 million years ago—on the eve of the Cambrian Explosion—that atmospheric and oceanic oxygen levels reached thresholds sufficient to support diverse, energy-demanding multicellular organisms.

Microbial Alchemy: Turning Sunlight into Biosphere

Photosynthesis is more than just a way to make sugar. It is the ultimate form of planetary engineering—reshaping air, climate, rock, and life. By mastering this process, cyanobacteria became not only survivors, but planet-makers.

They are still with us today—in every leaf, every blade of grass, every pond’s green shimmer. The oxygen you breathe now was made possible by ancient cells in primeval seas.

From the quiet bloom of sunlight within a single-celled cyanobacterium emerged the great exhalation of a living world.

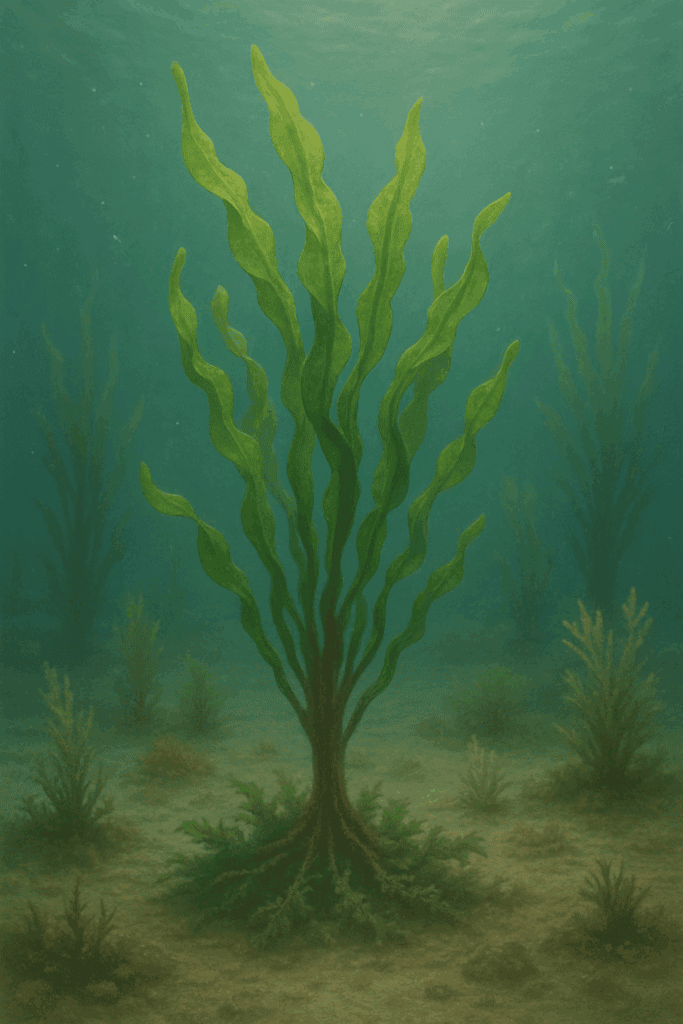

VII. The First Plants on Earth

Greening the Planet: From Algae to Mosses

Long before forests blanketed continents and flowering plants adorned the land, the ancestors of all terrestrial vegetation lived quietly in the oceans. These early photosynthetic organisms—algae—were the first plants on Earth, and their evolution not only transformed marine ecosystems, but laid the groundwork for life on land.

Algae: The Primordial Photosynthesizers

The earliest plant-like organisms were simple algae—aquatic, photosynthetic eukaryotes that appeared between 1.6 and 1.0 billion years ago, shortly after the rise of eukaryotic cells. Unlike cyanobacteria, which are prokaryotic, algae had nuclei and internal compartments. They evolved when an ancestral eukaryote engulfed a cyanobacterium, which then became a permanent resident—the first chloroplast.

Algae diversified into major groups, including:

- Green algae (Chlorophyta): Ancestors of all land plants

- Red algae (Rhodophyta): Adapted to deeper waters

- Brown algae (Phaeophyceae): Later evolved into large forms like kelp

Algae built the first true plant cells, complete with cell walls made of cellulose, chlorophyll for photosynthesis, and the ability to store starch—traits that would become standard in terrestrial flora.

From Sea to Land: The Great Migration

Around 500 million years ago, certain green algae began adapting to the fluctuating conditions of shallow, freshwater environments—exposed to sunlight, desiccation, and air. These pressures selected for new structural and reproductive adaptations, giving rise to the earliest land plants.

Key traits that enabled this transition included:

- Protective cuticles to retain moisture

- Stomata for gas exchange

- Anchoring rhizoids (root-like structures)

- Spores with resilient walls for survival in air

- Symbiosis with mycorrhizal fungi to obtain nutrients from rocky soil

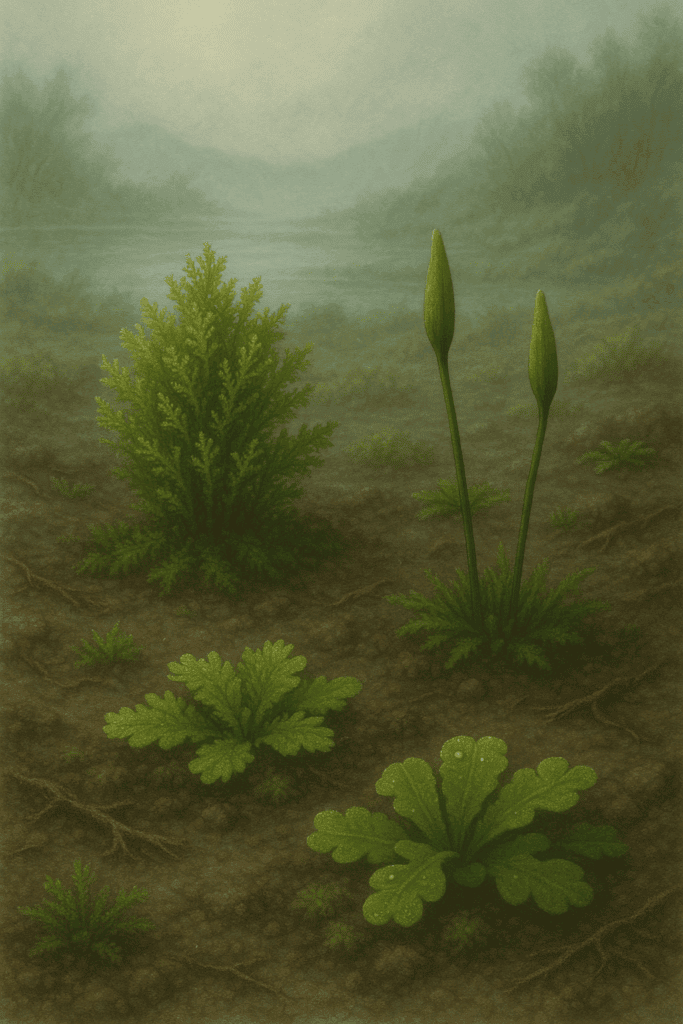

Non-Vascular Pioneer Plants

The first true land plants were non-vascular—they lacked roots, stems, and leaves as we know them. Dominant groups included:

- Liverworts (Marchantiophyta)

- Mosses (Bryophyta)

- Hornworts (Anthocerotophyta)

These plants formed low mats across moist landscapes and stabilized soils, helped form early terrestrial biomes, and continued the process of oxygenation on land.

Their arrival around 470 to 430 million years ago marked a decisive moment: the colonization of Earth’s continents by life.

Ecological Impact of Early Plants

As plants spread, they transformed Earth in profound ways:

- Increased photosynthetic oxygen production

- Created new microhabitats for microbes and early animals

- Influenced weathering of rocks and formation of soil

- Altered the carbon cycle, contributing to long-term cooling

These humble pioneers laid the green foundation for everything that followed: insects, amphibians, forests, agriculture, and civilization itself.

From drifting algae in ancient seas to mosses carpeting the first continental outcrops, the story of plants is one of expansion, resilience, and Earth-shaping power. Their arrival was not loud, but it was revolutionary.

VIII. The First Animals on Earth

From Simple Cells to Soft-Bodied Sentience

As plants began greening the planet’s edges, another miracle was unfolding beneath the waves. The first animals—complex, multicellular organisms with specialized cells—emerged from the world of single-celled simplicity. These pioneers of animal life evolved in Earth’s oceans, their soft bodies drifting or crawling across microbial mats long before shells or skeletons were imagined.

What Is an Animal?

Animals are defined by several key features:

- Multicellularity: Composed of many cells with specialized functions

- Heterotrophy: They must consume other organisms for energy

- Motility: Most are capable of movement at some life stage

- Development: Many go through embryonic stages like the blastula

- Tissue differentiation: Including muscles and nerves in more advanced forms

The evolution of animals required significant genetic innovation—especially the development of collagen, cell adhesion molecules, and regulatory genes like Hox genes, which guide body plan formation.

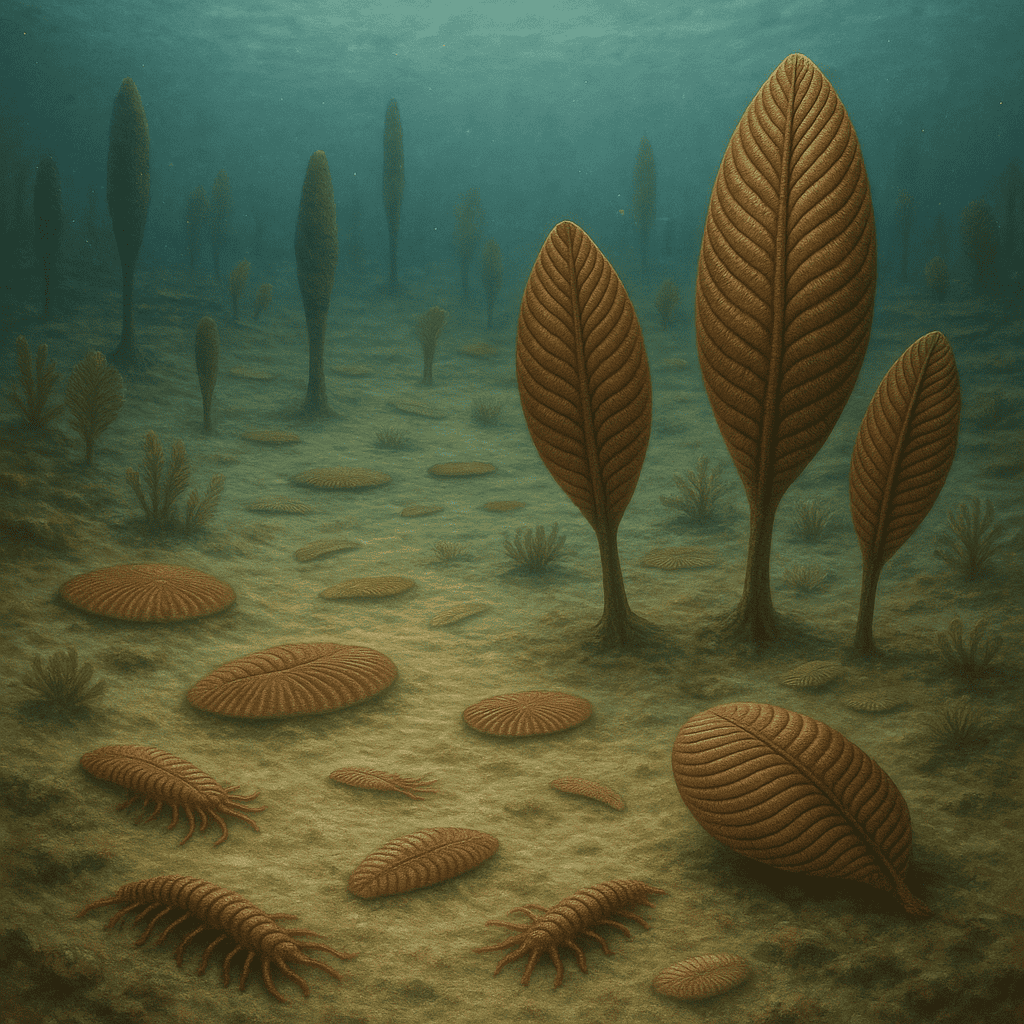

The Ediacaran Biota (635–541 Million Years Ago)

The earliest known animals appear during the Ediacaran Period, in the final chapter of the Precambrian Era. These creatures, preserved as impressions in sedimentary rock, represent Earth’s first macroscopic, multicellular fauna.

Key features:

- Mostly soft-bodied organisms, some resembling fronds, disks, or quilted pillows

- Likely sessile or slow-moving, grazing on microbial mats or absorbing nutrients

- Many had radial or bilateral symmetry, hinting at body organization

Examples include:

- Dickinsonia: A flat, ribbed oval-shaped organism, possibly an early animal

- Charniodiscus: A stalked frond-like creature anchored to the sea floor

- Spriggina: A segmented, worm-like form with a possible head-tail distinction

Though their precise classification remains debated, many paleontologists consider the Ediacaran fauna to be early animals, ancestral to later groups.

Sponges and Simple Metazoans

Among the earliest animals with living representatives are sponges (Phylum Porifera). Emerging perhaps as early as 700 million years ago, sponges lack nerves or muscles but have:

- Specialized collar cells (choanocytes) for filtering food

- A porous body plan adapted to water flow

- The ability to regenerate from fragments

Sponges represent a basal lineage of the animal kingdom and may bridge the evolutionary gap between single-celled protists and more complex animals.

Toward Mobility and Predation

The late Ediacaran world likely included early forms of:

- Cnidarians: ancestors of jellyfish and corals, with simple nerve nets

- Bilaterians: organisms with bilateral symmetry and a front-back orientation, leading to worms and ultimately vertebrates

- Trace fossils: Burrows and tracks in the sediment suggest that some animals could move, seek food, or avoid threats—hallmarks of behavior.

These early experiments in body organization and mobility set the stage for the Cambrian Explosion, where animal life would rapidly diversify into the ancestors of nearly every modern phylum.

A World Alive with New Sensation

In the first animals, the world gained something it had never known: sensation, response, and interaction. Soft though they were, these beings could now feel their environment, move toward light or away from predators, and shape their world not just chemically, but behaviorally.

The Earth’s biosphere—until then a quiet realm of microbial processes—had begun to stir with perception and agency.

IX. The First Mobile Life Forms

Motion: A New Way to Engage the World

The ability to move—intentionally, directionally, in response to stimuli—marks one of the most profound evolutionary innovations in the history of life. While microbes can drift, twitch, or glide, true locomotion arose much later, after multicellularity and tissue specialization allowed for muscular coordination and nervous signaling.

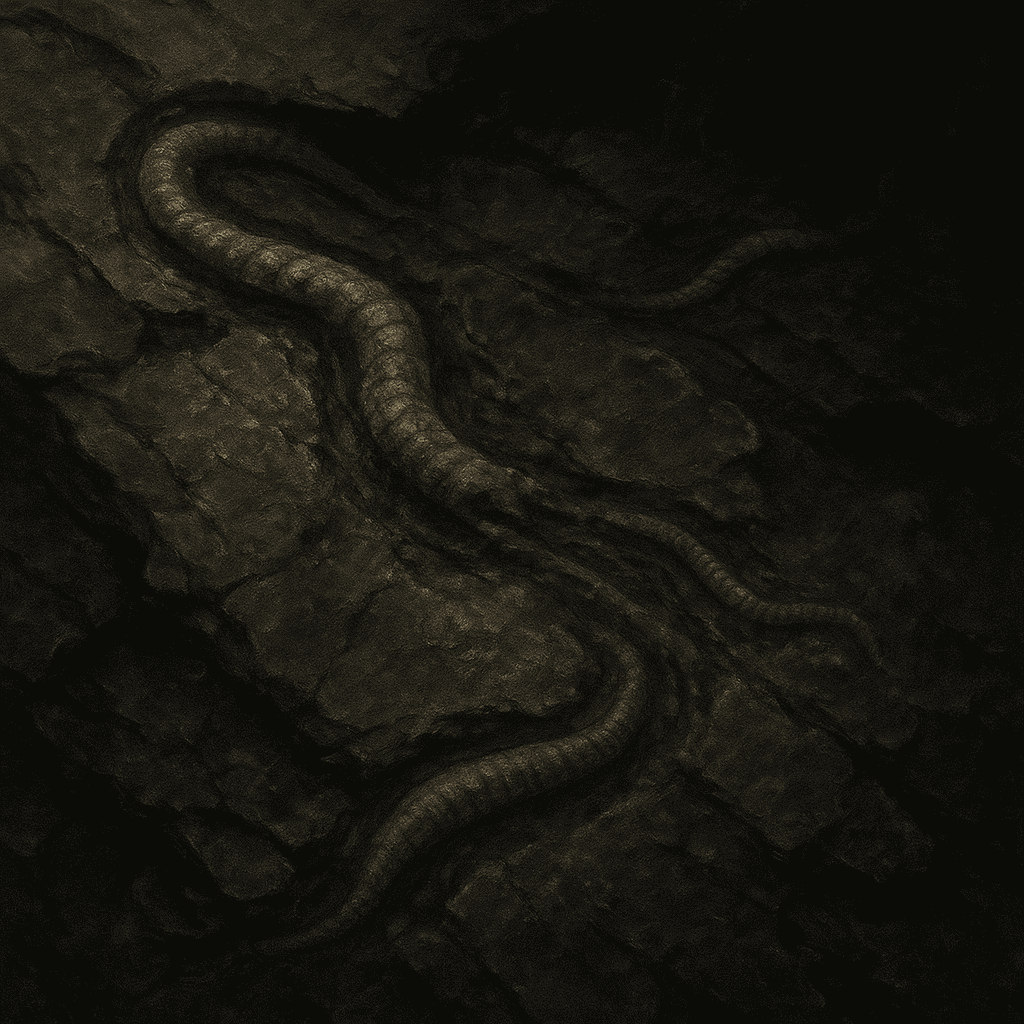

The earliest known evidence of mobile life forms dates to an extraordinary discovery in Gabon, West Africa, where fossils preserved in black shale deposits have revealed signs of ancient organisms capable of movement—over two billion years ago.

Gabon’s Mysterious Movers (c. 2.1 Billion Years Ago)

In 2010, researchers uncovered fossilized tubular trails—tiny trackways etched into sediment—indicating that some multicellular organisms at the time were capable of directed movement through mud. These traces were left by soft-bodied, presumably oxygen-dependent organisms, making their way through shallow, oxygenated coastal environments.

Although the exact identity of these organisms remains unclear, their significance is enormous:

- They are the oldest known evidence of motility by complex life

- Their activity suggests coordinated behavior, possibly using muscle-like tissues

- They imply that life experimented with complexity and movement far earlier than previously believed

Yet this early burst of complexity did not last. These mobile forms seem to have vanished as oceanic oxygen levels later declined. Evolution, it seems, does not always move in a straight line—it is a branching, experimental process.

Rise of Bilaterians and Symmetry for Movement

Later, during the Ediacaran Period (635–541 million years ago), organisms began to evolve bilateral symmetry—a head and tail, a top and bottom, left and right sides. This configuration allows for:

- Directional movement (forward/backward)

- Cephalization (concentration of sensory organs in the “front”)

- Streamlined body shapes for burrowing or swimming

Such animals likely included early worms—creatures that could crawl through sediment, leaving behind the first trace fossils, such as burrows, grooves, and feeding trails.

Why Mobility Matters

The ability to move transformed evolutionary dynamics by introducing:

- Predation and escape: Life could now actively hunt or flee

- Territoriality and exploration: Organisms could find new habitats or food

- Behavioral complexity: Movement enabled sensory input to guide survival strategies

- Sexual reproduction: Movement allowed for mate-finding and dispersal of offspring

In short, mobility turned the biosphere into an ecological stage of dynamic interactions, where movement became both a survival strategy and a creative force in evolution.

The Dawn of Behavior

With motion came behavior. Life was no longer simply reacting through chemical feedback—it was engaging, choosing, and interacting with its environment in complex, proactive ways.

The first steps, crawls, and glides etched into Earth’s mud would echo through evolutionary history—culminating in the graceful swim of the ammonite, the leap of the cat, the flight of the hawk, and the dance of a human being.

X. The Earliest Biomes and Ecological Networks

Life’s First Ecosystems: Webs Without Roots or Wings

As life diversified and organisms began to interact with one another and their environments, Earth’s first biomes and ecological networks emerged. These were not forests or coral reefs as we know them, but simple, ancient zones of microbial activity and primitive multicellular life—worlds of chemical gradients, shallow seas, hydrothermal vents, and microbial colonies.

In these early stages, life was both the builder and inhabitant of its environment. The separation between biology and geology was still thin, with ecosystems shaped as much by mineral flows and atmospheric gases as by biology itself.

Hydrothermal Vent Biomes: The Wombs of Life

Deep beneath the oceans, at tectonic boundaries where magma met seawater, hydrothermal vents gushed mineral-rich fluids into the abyss. These vents—still active today—are among the most likely cradles of life.

- Chemosynthetic microbes harnessed the energy of hydrogen sulfide and other inorganic compounds, producing organic matter without sunlight.

- Vent chimneys created natural chambers—micro-environments that supported microbial colonies.

- These ecosystems operated in complete darkness, relying entirely on geochemical energy.

These were Earth’s first food webs, and they are still inhabited by some of the most ancient lineages of life.

Shallow Sea Biomes: The Microbial Mat Worlds

In warmer, sunlit regions, shallow coastal seas and intertidal zones hosted extensive microbial mats—thick layers of cooperating bacteria, archaea, and early algae. These biomes were:

- Structured in chemical and metabolic layers: anaerobic bacteria at the bottom, photosynthesizers at the top

- Protected by sticky extracellular matrices that helped trap sediment, eventually forming stromatolites

- Sites of localized oxygen production, giving rise to oxygen oases before the atmosphere became fully oxygenated

These mats formed the living crusts of Earth’s early surfaces, stabilizing sediments and altering local chemistry, setting the stage for more complex ecosystems.

Terrestrial Microbial Crusts: Life on Land Begins

While life originated in the oceans, microbial life was also present on land earlier than once thought. Around 3.2 to 2.5 billion years ago, microorganisms likely colonized:

- Wet volcanic rocks and geothermal soils

- Mineral-rich hot springs

- Transient freshwater ponds and shoreline zones

These microbial crusts were resilient and cooperative. Some even formed symbiotic associations with fungi, anticipating the mycorrhizal relationships that would later support terrestrial plants.

Ecosystem Feedback: Life Alters the Earth

Even these simple biomes created feedback loops:

- Oxygen production changed atmospheric chemistry

- Microbial respiration affected carbon cycles and ocean pH

- Sulfur, nitrogen, and iron cycling emerged from microbial metabolism

- Sediment stabilization influenced erosion and soil formation

These processes created the first ecological networks, even without food chains as we understand them. Energy flowed from hydrothermal heat or sunlight to microbial producers, and eventually to grazers and decomposers—laying the metabolic foundation for all future life.

The Earth Becomes an Ecosystem

In these ancient environments, life and Earth co-evolved. There was no “natural world” separate from living things—life was geology, and vice versa. The first biomes were not just places where life happened to exist; they were life’s own creations, continually reshaped by the organisms within them.

These primitive ecosystems whisper the earliest version of a truth that still holds: life sustains life—not through dominance, but through interdependence.

XI. Toward Complexity: Prelude to Dinosaurs

The Long March Toward Megafauna

By the end of the Precambrian, life had laid down the foundation: cells, energy systems, photosynthesis, respiration, locomotion, tissues, and early ecological webs. What followed was one of the most explosive periods in Earth’s biological history—a time when life diversified in form, function, and strategy, giving rise to nearly every major body plan seen today.

This transition into complexity, though rooted in the deep past, would ultimately lead to dinosaurs, mammals, birds, forests, and modern biodiversity. But it began in the sea, as most major evolutionary transformations have.

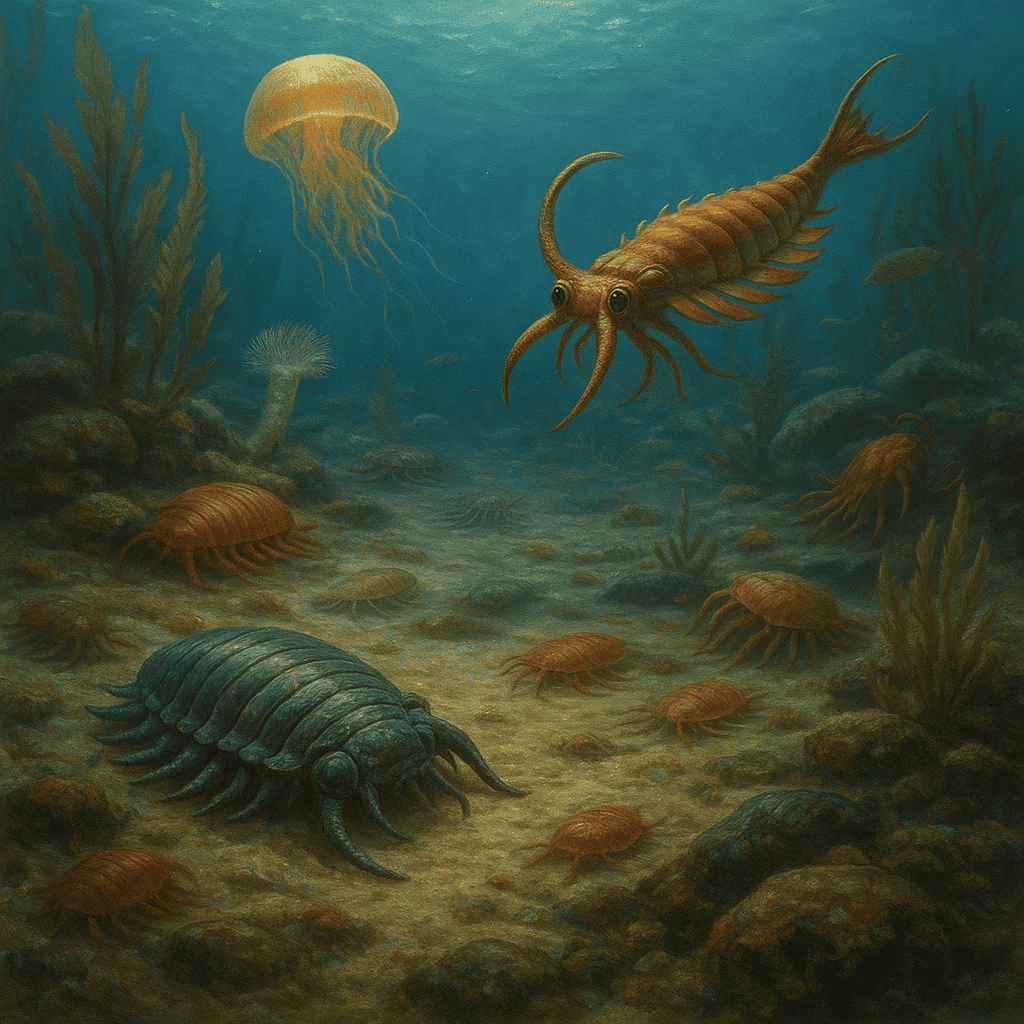

The Cambrian Explosion (c. 541–485 Million Years Ago)

During this brief geological window—only about 55 million years—animal life underwent an unprecedented radiation of diversity. Nearly all existing animal phyla (major body plan groups) appeared in the fossil record, including:

- Arthropods (insects, crustaceans, trilobites)

- Mollusks (snails, squid)

- Annelids (segmented worms)

- Chordates (including vertebrates)

- Echinoderms (sea stars, sea urchins)

Creatures such as Anomalocaris, a predatory arthropod, and Wiwaxia, a bizarre armored grazer, illustrate the experimental spirit of early animal evolution.

Drivers of this explosion may include:

- Rising oxygen levels in oceans

- Development of vision and predation

- Genetic innovations like Hox gene expansion

- Co-evolutionary arms races between predators and prey

The Rise of Vertebrates

Among the Cambrian innovations was the evolution of the notochord, a flexible rod that would give rise to the spinal columns of vertebrates. The earliest known vertebrates, such as Haikouichthys, had:

- A primitive backbone-like structure

- Gills and a tail for swimming

- Muscle bands for undulatory motion

These small, agile swimmers set the stage for fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals.

Colonization of Land (500–400 Million Years Ago)

While marine life flourished, plants and fungi began colonizing land, stabilizing soil and creating terrestrial habitats. Soon after, arthropods followed, becoming the first animals to walk on land.

Key developments:

- Vascular tissue in plants (xylem and phloem)

- Protective cuticles and seeds

- Exoskeletons in insects and scorpions

- Lungs and air-breathing adaptations in early tetrapods

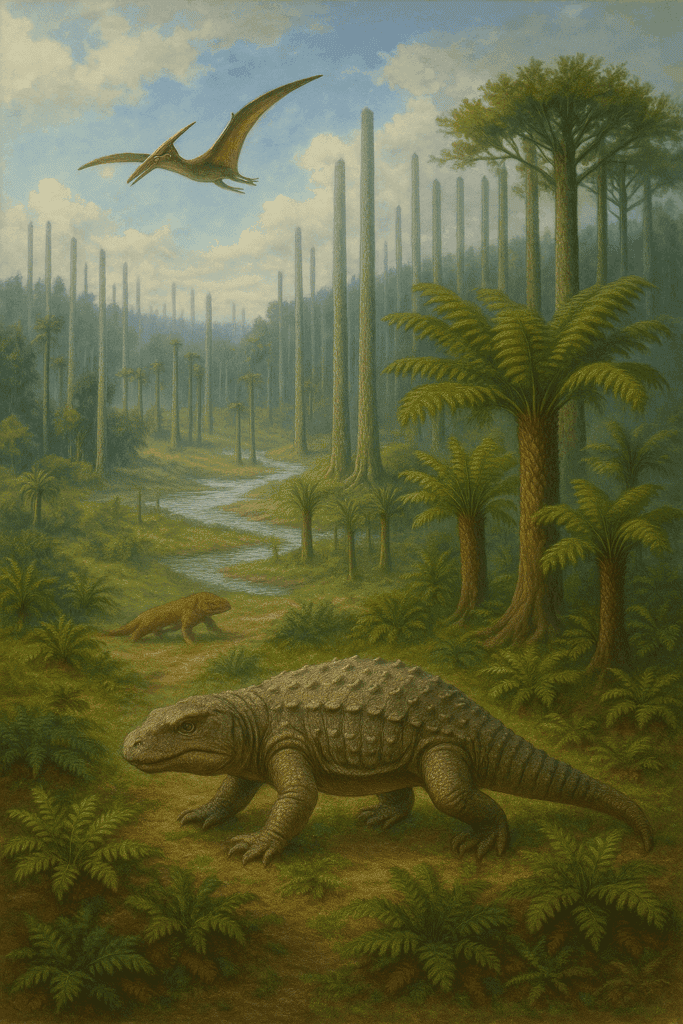

Tetrapods and the Amphibian Age (c. 370 Million Years Ago)

Lobed-finned fish like Tiktaalik bridged the gap between aquatic and terrestrial life. Over time, these fish evolved into amphibians—the first true land vertebrates.

These creatures still depended on water for reproduction, but they began to occupy new ecological niches—swamps, forests, and freshwater environments teeming with life.

Forests, Insects, and Carboniferous Complexity

By the Carboniferous Period (c. 360–300 Ma), Earth was covered in vast tropical forests. Gigantic ferns, horsetails, and clubmosses towered above the ground, forming dense canopies and thick peat beds that would later become coal.

- Insects grew to enormous sizes (e.g. Meganeura, a giant dragonfly with a 2.5-foot wingspan)

- Amphibians diversified

- The first reptiles emerged—animals no longer tied to water for reproduction

These evolutionary advances cleared the path toward the Age of Reptiles—an era that would reach its full expression in the Mesozoic, the age of dinosaurs.

The Threshold of the Dinosaur Era

As the Permian Period (299–252 Ma) closed with the largest mass extinction in Earth’s history, new ecosystems and life forms emerged from the ashes. Among them were the early archosaurs—ancestors of both crocodiles and dinosaurs.

The stage was now set.

Conclusion: From Molecules to Monsters

In the vast theater of Earth’s history, life began as a chemical whisper in ancient seas—and unfolded into a planet-spanning epic of innovation. By the close of the Paleozoic Era, life had:

- Developed cells, tissues, organs, and skeletons

- Learned to breathe, move, sense, and reproduce

- Colonized land, air, and every ocean depth

- Created the conditions for enormous, complex creatures like dinosaurs to emerge

The story of life was still young. The next act—The Age of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Giants—would transform Earth once again.