Table of Contents

- Introduction – What Is Engineering?

Defining engineering, its global roots, and its evolving role in civilization. - I. Ancient Foundations (Prehistory–500 CE)

From stone tools to pyramids and aqueducts: early global ingenuity. - II. Medieval and Islamic Golden Age (500–1500 CE)

Automata, cathedrals, canals, and waterwheels in a world of rediscovery. - III. Renaissance to Enlightenment (1500–1800)

Engineering meets science, art, and the rise of theoretical design. - IV. The Industrial Revolution (1800–1900)

Steam, steel, and the mechanical transformation of society. - V. The Age of Infrastructure and Invention (1900–1950)

Skyscrapers, electricity, computing, and wartime innovation. - VI. Space Age and Information Age (1950–2000)

From moon landings to microchips: the digital and cosmic frontiers. - VII. Engineering in the 21st Century (2000–Present)

Smart cities, sustainability, AI, and global collaboration. - VIII. Types of Engineering – A Comprehensive Overview

Civil, mechanical, biomedical, software, and emerging hybrid fields. - IX. The Future of Engineering

Fusion, ethics, planetary stewardship, and the new moral frontier. - X. Timeline of Engineering History

A chronological chart of major milestones and inventions. - Conclusion – Engineering the Future of Humanity

Toward ethical design, integration, and a sustainable civilization.

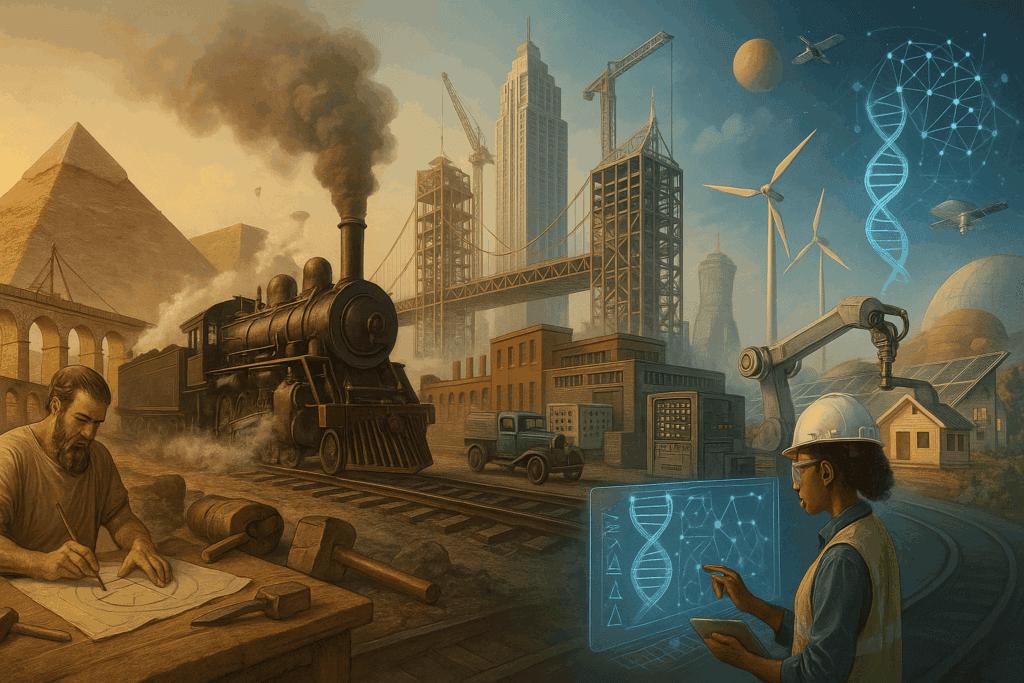

Introduction – What Is Engineering?

Engineering is the application of science, mathematics, and creative design to solve practical problems and build the structures, systems, and technologies that shape human civilization. From the first stone tools to the algorithms guiding autonomous vehicles, engineering has served as a bridge between the theoretical and the tangible, the natural and the artificial.

Unlike pure science, which seeks to understand the fundamental laws of the universe, engineering is concerned with using that knowledge to construct tools, machines, and systems that meet human needs. It is a discipline rooted in invention, iteration, and ingenuity—blending analytical precision with imaginative design.

Historically, engineering has emerged independently across cultures and continents. Ancient Egyptians engineered pyramids with astonishing precision. Chinese engineers designed massive canals, clocks, and gunpowder weapons. Indian metallurgists forged rust-resistant iron pillars. Greek thinkers formulated mechanical principles still used today. In each case, engineering developed as both an art and a science, shaped by the environment, materials, and social systems of the time.

Over millennia, engineering evolved from artisanal crafts to professionalized disciplines. The rise of universities, industrial manufacturing, and digital computation transformed it into a vast network of specialized fields—from civil and mechanical to aerospace, biomedical, and software engineering. Each of these domains follows a core methodology: identifying a challenge, designing a solution, building a prototype, testing and refining, and delivering a functional result.

Today, engineering plays a critical role in addressing global challenges: infrastructure and energy, food and water systems, climate change, medicine, transportation, and communications. As we enter the Age of Intelligence, the engineering profession must increasingly align itself with ethical foresight, sustainability, and inclusive progress.

This article charts the global history of engineering, examining its key phases, figures, innovations, and disciplines—before exploring the visionary frontier of engineering’s future. It concludes with a timeline that traces the arc of engineering from prehistory to our planetary tomorrow.

I. Ancient Foundations (Prehistory–500 CE)

Engineering began not with blueprints or formal theory, but with survival. In the prehistoric world, early humans applied intuitive knowledge to craft tools, build shelters, and manipulate their environment. These humble beginnings laid the groundwork for the monumental engineering feats of ancient civilizations.

Prehistoric Ingenuity

Stone tools such as hand axes, fire-hardened spears, and grinding stones represent the earliest forms of applied engineering. The discovery of fire, the shaping of bone and flint, and the construction of early dwellings all required a trial-and-error mastery of natural materials and forces.

As communities developed, so did techniques for irrigation, fortification, and transportation. Neolithic people in Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indus Valley, and China engineered early settlements with roads, walls, and water systems—many of which formed the core infrastructure of future cities.

Mesopotamia and Egypt

The Mesopotamians, living between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, were among the first to develop complex irrigation systems and levees to control flooding. They also built ziggurats—temple structures requiring sophisticated logistics and masonry.

Egyptian engineers constructed pyramids, temples, and tombs with such precision that many still stand today. Their knowledge of surveying, stone-cutting, and labor management was advanced enough to produce the Great Pyramid of Giza, aligning perfectly with cardinal points and showcasing load-bearing principles still studied today.

India and the Indus Valley

The Indus Valley Civilization (c. 2600–1900 BCE) featured advanced urban planning, including grid-pattern cities, standardized fired-brick buildings, drainage systems, and public baths. This civilization also pioneered hydraulic engineering with wells, reservoirs, and covered sewers.

China

Ancient Chinese engineers made lasting contributions in multiple domains:

- Hydraulic engineering: massive canal systems like the Dujiangyan irrigation system (3rd century BCE).

- Mechanical engineering: Zhang Heng’s seismograph (132 CE) and the south-pointing chariot, an early non-magnetic directional device.

- Military and civil innovation: development of the crossbow, early suspension bridges, and the Great Wall.

Greco-Roman Engineering

In Greece, philosophers like Archimedes laid theoretical foundations of levers, pulleys, and buoyancy that engineers would apply in practice. Heron of Alexandria devised primitive steam engines and automated devices.

The Romans mastered civil and military engineering. Their roads, aqueducts, and concrete buildings exemplified large-scale infrastructure. Vitruvius, a Roman military engineer, authored De Architectura, a foundational text blending architecture, engineering, and aesthetics.

Mesoamerica and the Andes

While often overlooked in Eurocentric accounts, Indigenous engineers in the Americas achieved remarkable feats. The Olmecs, Maya, and later the Aztecs built pyramid-temples, causeways, and aqueducts. The Incas engineered mountain terraces, rope bridges, and a vast road system through the Andes without wheeled vehicles or iron tools.

This era reveals a key truth: engineering is a universal human endeavor. From the Nile to the Yangtze, from the Andes to the Indus, ancient peoples shaped the Earth to suit their needs—and in doing so, built the first great monuments of civilization.

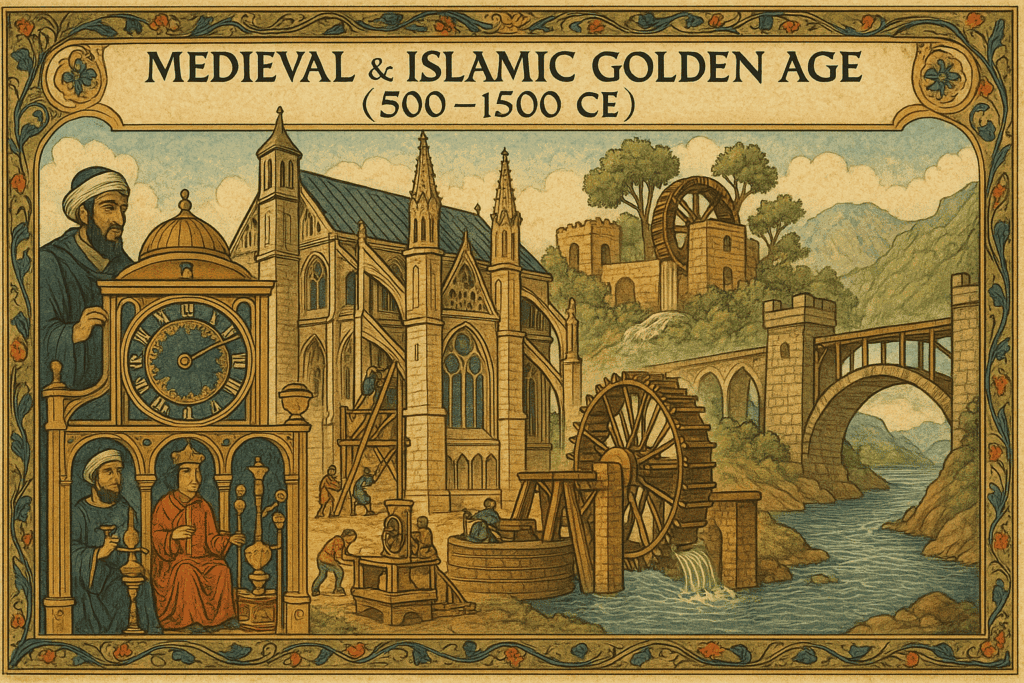

II. Medieval and Islamic Golden Age Engineering (500–1500 CE)

The collapse of the Western Roman Empire marked a shift in engineering development across Europe, while simultaneously ushering in a golden age of scientific and technological innovation in the Islamic world. Asia continued to advance independently, and new forms of engineering emerged across diverse civilizations—from windmills in Persia to cathedrals in Europe and advanced metallurgical work in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Europe: From Survival to Structural Grandeur

In early medieval Europe, engineering knowledge was largely preserved in monasteries and military workshops. Castles, fortifications, and catapults were central to feudal warfare. Agricultural engineering advanced with the invention of the heavy plow, the horse collar, and three-field crop rotation, leading to improved productivity.

By the High Middle Ages (11th–13th centuries), cathedral construction showcased extraordinary achievements in civil and structural engineering. Builders developed flying buttresses, ribbed vaults, and pointed arches—enabling the elevation of Gothic cathedrals like Notre-Dame and Chartres, fusing architecture and engineering into sacred monuments.

Water power also flourished during this period. Waterwheels powered flour mills, fulling mills, and iron forges, marking a quiet revolution in mechanical energy.

The Islamic Golden Age: Scientific and Mechanical Brilliance

From the 8th to 14th centuries, Islamic civilization became a global hub of intellectual and engineering advancement. Muslim engineers, scholars, and artisans synthesized Greek, Persian, Indian, and local knowledge to produce new inventions and infrastructures.

Key figures and innovations:

- The Banu Musa brothers (9th century): authors of The Book of Ingenious Devices, which described early automation and mechanical systems, including fountains, valves, and self-operating machines.

- Al-Jazari (12th century): created intricate automata, geared water clocks, pumps, and mechanisms that later influenced Renaissance engineers. His Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices remains a landmark in the history of mechanical engineering.

- Irrigation engineering: the development of qanats (subterranean aqueducts), norias (water wheels), and wind towers for passive cooling showed environmental mastery.

- City infrastructure: urban centers like Baghdad, Cairo, and Cordoba had paved roads, public baths, libraries, sewage systems, and bridges that surpassed much of contemporary Europe.

China and East Asia

China’s Song Dynasty (960–1279) was a high point in technological development:

- Gunpowder and military engineering advanced with rockets, flame-throwers, and early grenades.

- Movable type printing, pioneered by Bi Sheng, transformed information dissemination.

- Bridge engineering reached new heights with iron-chain suspension bridges and segmental stone bridges (e.g., the Zhaozhou Bridge, built c. 605 CE).

- Mechanical innovation: Su Song’s astronomical clock tower (11th century) combined hydraulics, gears, and escapements centuries ahead of Europe.

Japan, Korea, and Southeast Asia also made notable advances in temple construction, metallurgy, and hydrology, often adapting Chinese technologies to local needs.

Africa and the Americas

- West Africa: The cities of the Mali and Songhai Empires had planned streets, public infrastructure, and advanced ironwork. While much of the knowledge was oral, the engineering required to construct adobe mosques like Djenné was sophisticated and enduring.

- The Andes: The Inca expanded their engineering legacy with earthquake-resistant masonry, agricultural terraces, and freeze-dried food storage systems (chuño), displaying deep adaptation to harsh mountain environments.

- Mesoamerica: Aztecs engineered the floating gardens (chinampas) of Tenochtitlan, along with dikes and aqueducts to manage water in their lake-centered capital.

This era laid the foundation for modern engineering by preserving and expanding upon ancient knowledge. While European engineering began to stir again in preparation for the Renaissance, it was the Islamic world and Asia that held the torch of innovation through the so-called “Dark Ages” of Europe.

III. Renaissance to Enlightenment (1500–1800)

The Renaissance and Enlightenment periods witnessed the rebirth of scientific inquiry in Europe, fueled by rediscovered classical texts, global exploration, and rapid social transformation. Engineering evolved from a primarily practical craft to a discipline increasingly rooted in empirical observation and mathematical principles. This era marks the emergence of the modern engineer—not just as a builder, but as a theorist and designer.

The Renaissance: The Visionary Engineer-Artist

The Renaissance (14th–17th centuries) blended art, science, and technology. Its polymaths laid the groundwork for conceptual design in engineering:

- Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) remains the most iconic figure. His notebooks include blueprints for helicopters, tanks, bridges, and water-lifting devices. While many of his machines were never built, his ability to fuse anatomy, geometry, and mechanics foreshadowed modern design thinking.

- Engineers like Filippo Brunelleschi applied classical knowledge to solve real-world problems, such as constructing the dome of Florence Cathedral using hoisting machines and innovative scaffolding techniques.

Scientific Foundations

The shift from qualitative speculation to quantitative science transformed engineering:

- Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) pioneered studies of motion and stress—providing a physical basis for mechanical engineering.

- Isaac Newton (1643–1727) developed the laws of motion and universal gravitation, critical to all later mechanical and structural engineering.

- Robert Hooke and Christiaan Huygens advanced clockwork, optics, and spring mechanics.

This growing emphasis on measurement and reproducibility laid the foundations for systematic experimentation—blending physics and engineering into a unified tradition.

Military and Civil Engineering

European states increasingly relied on engineers for war and empire-building:

- Military engineers revolutionized fort design with bastion systems that resisted cannon fire, particularly in Italy and France.

- Canals and locks connected rivers across England, France, and the Low Countries, improving trade and spurring mechanical innovations in navigation.

Naval engineering became a strategic art:

- The Age of Exploration depended on the development of ocean-worthy ships, navigational instruments (astrolabe, sextant), and cartography. Engineers like Sebastiano Serlio and Pierre Bouguer refined ship design and load-bearing theories.

Global Exchange and Engineering Knowledge

Colonialism enabled the flow of materials, technologies, and blueprints across continents—often unequally. European engineers learned from Chinese printing, Indian steel, and Arab mechanics. Simultaneously, indigenous techniques were appropriated, modified, or suppressed in colonial regions.

Printing technology—advanced and spread from its earlier Chinese origins—enabled the first engineering treatises to be published widely, disseminating technical knowledge across Europe.

This period transformed engineering into a more scientific and theoretical endeavor, preparing the way for the explosive industrial and mechanical revolutions that followed. In a world of growing cities, expanding empires, and evolving machines, the stage was set for engineering to reshape the modern world.

IV. The Industrial Revolution (1800–1900)

The Industrial Revolution was a seismic turning point in the history of engineering. Originating in Britain and spreading globally, it marked the transition from handcraft and agrarian economies to mechanized, urbanized societies powered by steam, coal, and steel. This era witnessed the emergence of professional engineers, the birth of new engineering disciplines, and a wave of innovations that forever changed the human landscape.

The Rise of Mechanical Engineering

At the heart of the Industrial Revolution was the mechanization of labor. This required a new class of professionals who could design, build, and maintain engines, machines, and factory systems.

- James Watt improved the steam engine in the late 18th century, but its wide-scale industrial use exploded in the 19th. Watt’s innovations in rotary motion and pressure control powered textile mills, mines, locomotives, and ships.

- The factory system, first seen in textiles, evolved into a general industrial model, with machines and conveyor systems designed for maximum efficiency.

- Machine tools, such as lathes and milling machines, allowed parts to be produced with precision and repeatability—ushering in modern manufacturing.

Civil and Structural Engineering: Infrastructure on a Massive Scale

The demands of a growing population and expanding commerce led to bold new feats in infrastructure:

- Railways emerged as the arteries of industrial society. Pioneers like George Stephenson and Isambard Kingdom Brunel built steam locomotives and extensive rail networks that unified entire countries and spurred urban growth.

- Bridges, tunnels, and viaducts tested new theories of stress, strain, and materials. Brunel’s Clifton Suspension Bridge and the Great Western Railway remain iconic.

- Urban centers rapidly expanded, requiring improved sanitation, water supply, roads, and public buildings. Civil engineering societies formed to professionalize the field and standardize training.

Chemical and Electrical Engineering Take Shape

- The 19th century saw the rise of chemical engineering, initially driven by demands in textile dyes, fertilizers, soap, glass, and later explosives. Processes like the Haber-Bosch method for ammonia synthesis would soon follow.

- Michael Faraday’s discoveries in electromagnetism laid the groundwork for electrical engineering. Nikola Tesla, Thomas Edison, and James Clerk Maxwell advanced the design and application of electrical systems for power generation, lighting, and communication.

- Telegraph and telephone systems introduced long-distance communication—a precursor to the information age.

Professionalization and Education

- Engineering moved from the workshop to the classroom. Institutions like École Polytechnique (France), MIT (USA), and Technische Hochschule (Germany) emerged to formalize engineering education.

- Engineering societies and journals were founded to set standards and facilitate knowledge exchange—turning engineering into a recognized, regulated profession.

By 1900, the modern engineer had fully emerged—trained in theory, tested in practice, and embedded in the systems that powered the industrial world. The revolution had not only transformed economies and cities, but also birthed a global engineering culture that would define the 20th century.

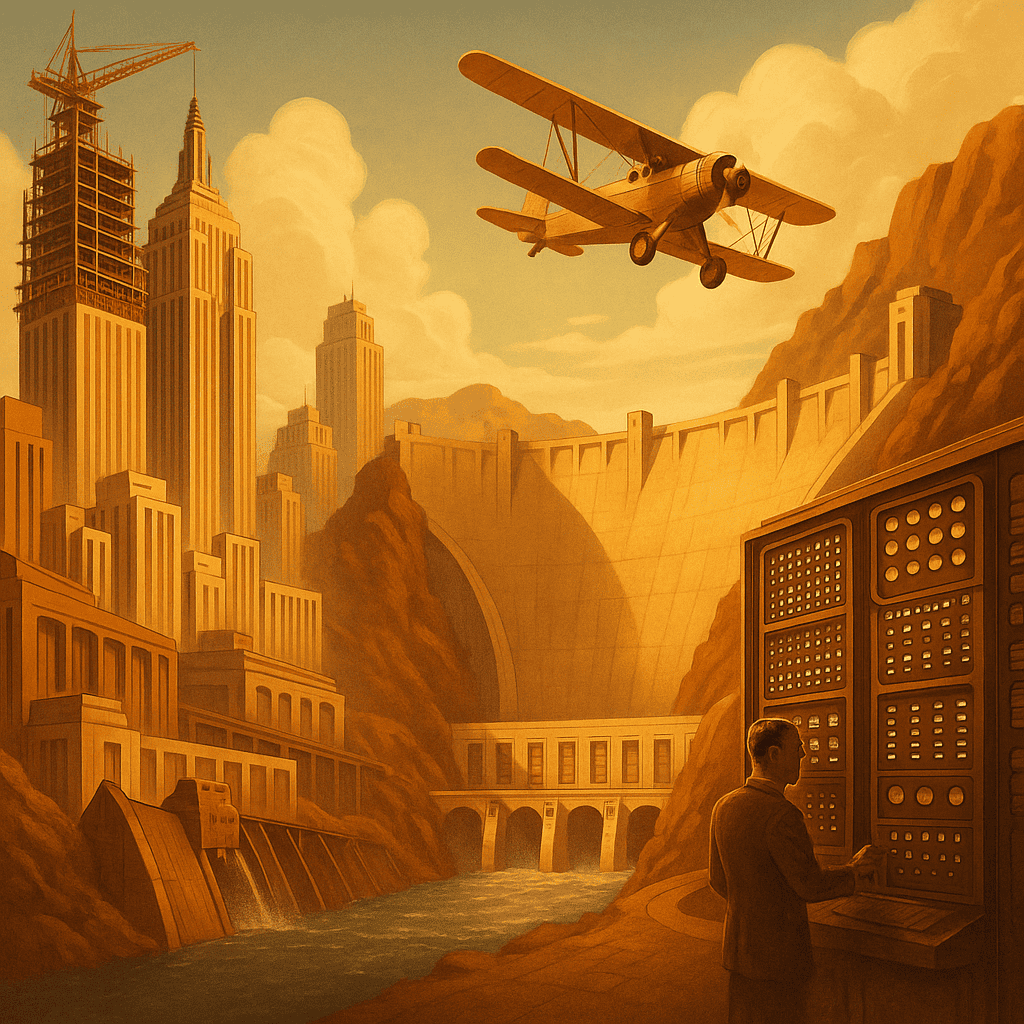

V. The Age of Infrastructure and Invention (1900–1950)

The first half of the 20th century was marked by monumental infrastructure projects, rapid technological breakthroughs, and the convergence of engineering with the global upheavals of war, urbanization, and industry. It was a period in which engineering scaled up—transforming cities, nations, and the human experience itself.

The Expansion of Civil Infrastructure

The early 20th century saw massive investments in national and urban infrastructure:

- Skyscrapers like the Empire State Building (1931) rose as steel-frame construction, elevators, and electrical systems revolutionized urban design.

- Dams such as the Hoover Dam (completed 1936) exemplified large-scale hydroengineering for power, water control, and agriculture.

- Highways, bridges, tunnels, and subways reshaped modern transportation. The Golden Gate Bridge (1937) pushed structural engineering to new aesthetic and technical heights.

Civil engineers became central to national development, and urban planning began to integrate transportation, zoning, sanitation, and energy into systemic designs.

Mechanical and Industrial Innovation

This period was also one of invention:

- The automobile industry revolutionized manufacturing with assembly lines (Henry Ford’s Model T, 1908), bringing engineering into mass consumer markets.

- Aviation engineering progressed from the Wright brothers (1903) to transatlantic flight and military aircraft by WWII.

- Industrial engineering grew as a field focused on workflow optimization, systems efficiency, and ergonomics—laying foundations for later systems engineering and operations research.

Electrical and Communications Breakthroughs

The electrification of cities and homes became widespread:

- Power grids expanded, supported by alternating current systems developed by Nikola Tesla and commercialized by Edison and Westinghouse.

- Radio engineering turned from hobbyist experimentation to mass communication, thanks to the work of Guglielmo Marconi, Lee de Forest, and others.

- Television, vacuum tubes, and early cathode ray tubes emerged, setting the stage for visual media and computing.

Computing and Control Systems

- Analog computing devices were developed for scientific and military applications.

- The first digital computers appeared during WWII. Alan Turing’s theoretical work and the construction of ENIAC (1945) by J. Presper Eckert and John Mauchly were watershed moments in the birth of computer engineering.

- Control systems, automation, and feedback theory began to influence engineering thought, especially in manufacturing and military technologies.

Engineering and War

World War I and especially World War II were catalysts for engineering innovation:

- Military needs accelerated research in rocketry, aeronautics, radar, and nuclear technology.

- Engineers developed everything from portable bridges (Bailey Bridge) to precision munitions and code-breaking machines.

- The Manhattan Project exemplified a new kind of “big science” engineering effort, involving thousands of specialists working toward a common, complex goal.

This was an age when engineering matured into a comprehensive force for modern civilization—reaching new heights of power and complexity, but also raising questions about ethics, consequences, and the role of engineers in society. It laid the groundwork for the space age and the digital revolution to come.

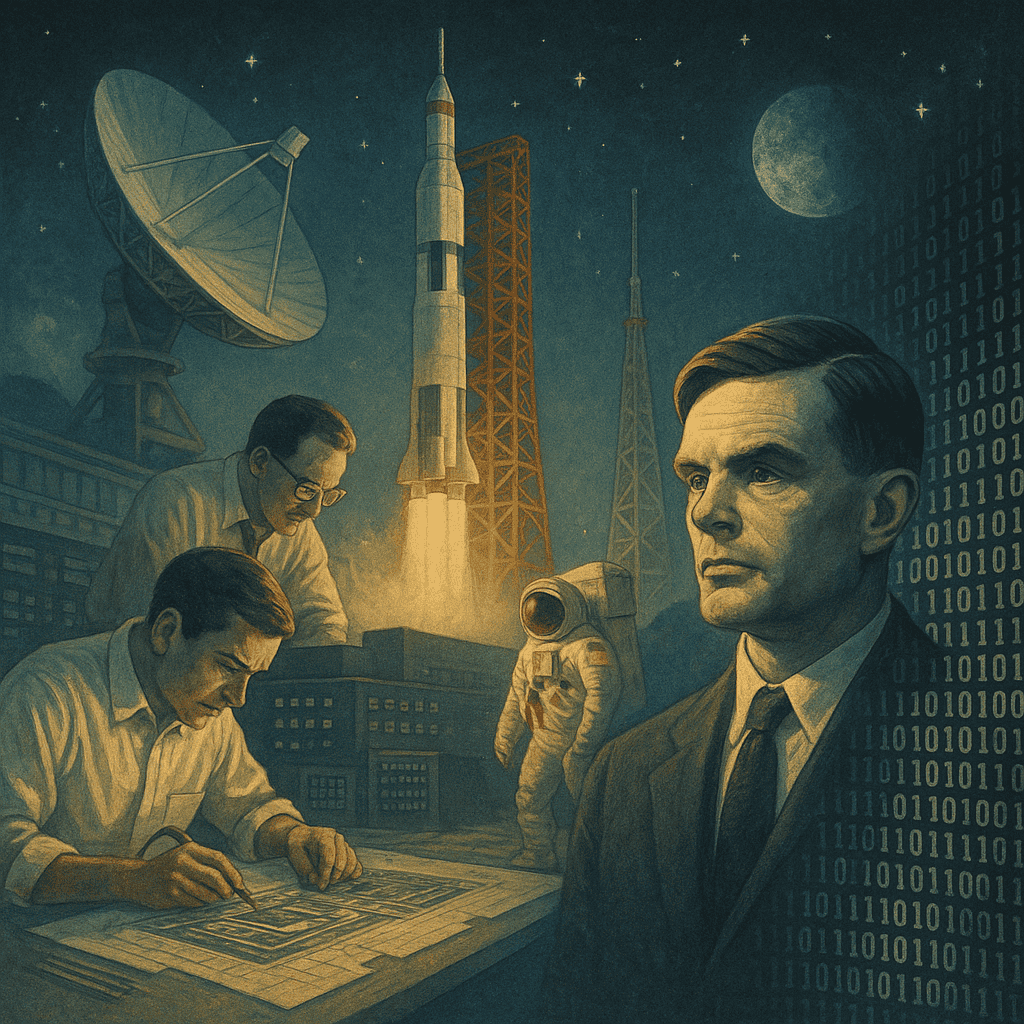

VI. Space Age and Information Age (1950–2000)

The second half of the 20th century saw engineering transcend Earth’s boundaries and enter the digital domain. As nations raced to the stars and networks formed across the globe, the fusion of science and engineering produced transformative technologies that reshaped every aspect of modern life. This era marked the rise of systems thinking, microelectronics, and the global digital infrastructure.

The Space Age: Engineering Beyond Earth

Triggered by Cold War rivalries, the Space Age pushed aerospace engineering to extraordinary new heights:

- In 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the first artificial satellite.

- In 1969, NASA’s Apollo 11 mission put humans on the Moon, the result of an immense multidisciplinary engineering feat involving aeronautics, computers, communications, and materials science.

- Wernher von Braun and Sergei Korolev led competing rocket programs, showcasing the global and political significance of engineering prowess.

- Satellite technology soon enabled GPS, weather forecasting, and global communication—bringing space engineering into everyday civilian life.

The Rise of Computer and Software Engineering

The development of computers redefined engineering:

- Alan Turing‘s theoretical groundwork on computation became a foundation for programming languages and machine logic.

- The transistor (invented in 1947) and later the integrated circuit revolutionized electronics, making possible smaller, faster, more efficient devices.

- The 1960s–80s saw the creation of mainframes, personal computers (Apple, IBM), and eventually the internet.

- Software engineering emerged as a discipline in its own right, with pioneers like Grace Hopper (COBOL) and Donald Knuth laying conceptual and practical foundations.

The Semiconductor and Digital Revolution

- Moore’s Law, articulated by Gordon Moore in 1965, predicted the exponential growth in processing power—a self-fulfilling prophecy driven by relentless innovation in microchip design and fabrication.

- Digital systems replaced analog controls in manufacturing, avionics, finance, and medicine.

- The World Wide Web, developed by Tim Berners-Lee in 1989, transformed the internet from a military-academic tool into a public communications revolution.

Systems and Industrial Engineering Evolve

- Large-scale systems—power grids, telecom networks, airline logistics, and nuclear plants—required integrated engineering across domains.

- Systems engineering formalized methods for managing complexity in design, production, and lifecycle.

- Operations research, simulation modeling, and control theory found widespread use in business, defense, and manufacturing.

Bioengineering and Materials Science Breakthroughs

- New materials such as carbon fiber, semiconductors, and biocompatible polymers expanded the engineer’s toolkit.

- Biomedical engineering developed pacemakers, prosthetics, and imaging technologies like MRI and CT scans.

- Genetic engineering emerged in the 1970s, leading to synthetic biology and biotech industries.

By the close of the 20th century, engineering was no longer just about machines or buildings—it was about systems, data, and life itself. The Space Age and the Information Age set the stage for an interconnected world shaped not only by physical infrastructure, but by networks of information, intelligence, and ethics.

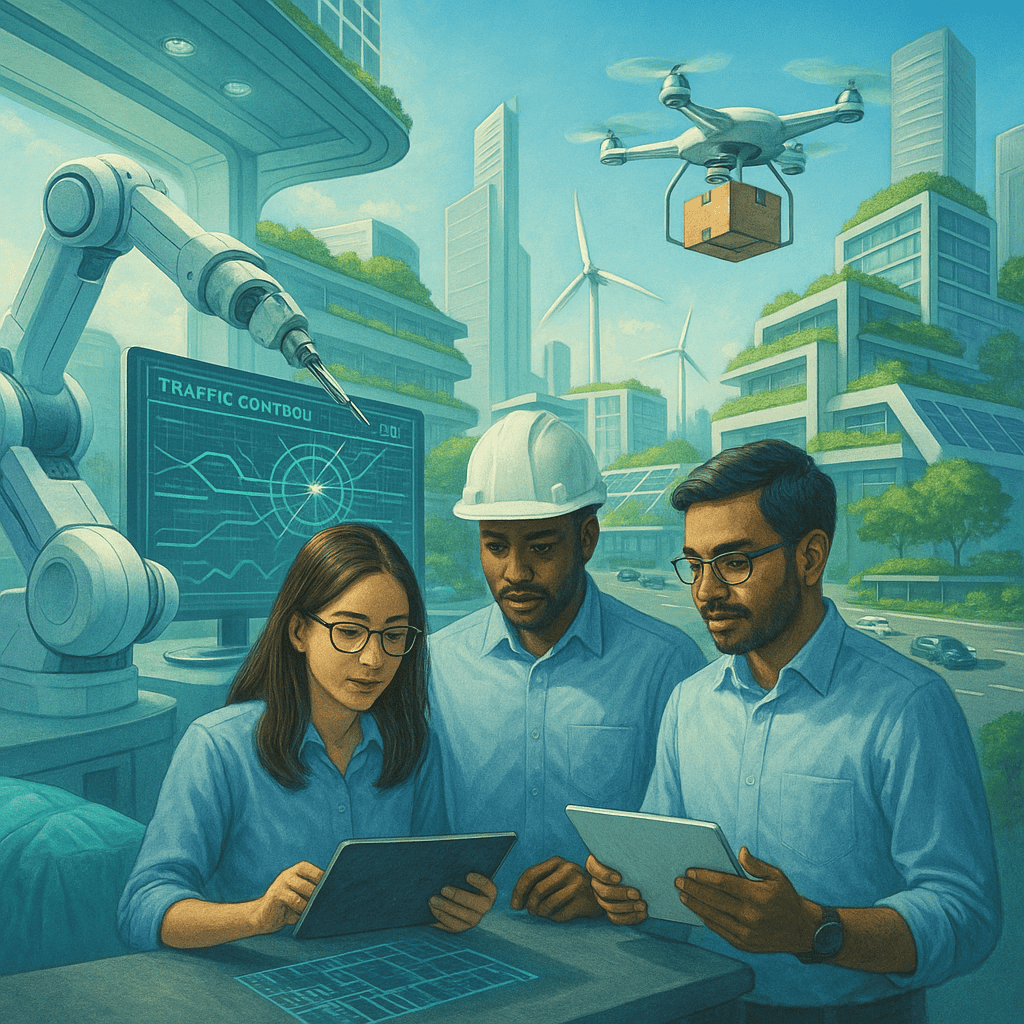

VII. Engineering in the 21st Century (2000–Present)

The 21st century has ushered in a new phase of engineering—one defined by sustainability, intelligence, biology, and global systems. Engineers today are not only problem-solvers but system designers, ethical innovators, and planetary stewards. The boundaries between physical, digital, and biological domains are dissolving, creating new fields, new responsibilities, and new frontiers.

Smart Technologies and Artificial Intelligence

- AI and machine learning now power systems in transportation (autonomous vehicles), healthcare (diagnostic tools), manufacturing (predictive maintenance), and daily life (voice assistants, recommendation engines).

- Robotics engineering has advanced dramatically—from precision surgical robots to warehouse automation, and from Boston Dynamics’ mobile machines to humanoid prototypes.

- Internet of Things (IoT) has networked everyday devices, enabling real-time data exchange and control across homes, cities, and industries.

Sustainable and Green Engineering

In response to climate change and resource depletion, engineering has shifted toward sustainability:

- Renewable energy systems—solar, wind, geothermal, and hydro—are being engineered for efficiency, resilience, and scalability.

- Green architecture and urban design apply environmental engineering principles to reduce emissions and optimize energy flows.

- Engineers are developing carbon capture, waste-to-energy, and closed-loop recycling technologies to transition from extractive to regenerative systems.

Biotechnology and Biomedical Frontiers

- Bioengineering now includes gene editing (e.g., CRISPR), synthetic biology, and tissue engineering.

- Medical devices, wearables, and nanomedicine are being tailored to individual health profiles through precision engineering.

- The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated innovation in rapid diagnostics, vaccine engineering, and global biomanufacturing networks.

Advanced Manufacturing and Materials

- 3D printing (additive manufacturing) allows rapid prototyping, localized production, and complex geometries in everything from aerospace to medicine.

- Smart materials, such as self-healing polymers and shape-memory alloys, enable dynamic structures that respond to stimuli.

- Quantum engineering is emerging, combining physics, materials science, and computer engineering in pursuit of revolutionary computational capabilities.

Digital Infrastructure and Cyber-Physical Systems

- Engineers are now building cyber-physical systems: tightly integrated networks of sensors, processors, actuators, and software. These underlie smart cities, autonomous vehicles, and high-frequency trading platforms.

- Blockchain engineering is reshaping digital trust, decentralized finance, and secure identity systems.

- Cloud computing and edge computing support massive, distributed applications with global reach and local responsiveness.

Global and Ethical Challenges

- Engineers today face new responsibilities: designing for global equity, data privacy, algorithmic transparency, and socio-technical resilience.

- Humanitarian engineering is gaining momentum, applying engineering principles to solve urgent problems in the developing world—clean water, shelter, energy access.

- Institutions are calling for a new engineering ethos that prioritizes ethics, inclusion, and sustainability as much as technical performance.

Engineering in the 21st century is not just advancing—it is transforming. As technology evolves faster than regulation or education, engineers must now act as ethical agents and civic leaders. The next era will not be defined by tools alone, but by how wisely we use them.

VIII. Types of Engineering – A Comprehensive Overview

Engineering today is a vast constellation of disciplines, each with its own methodologies, tools, and domains of application. Yet all share a common DNA: the systematic design and optimization of systems to solve human and planetary problems. Below is an overview of the major branches of engineering, as well as emerging and interdisciplinary fields that reflect the complexity of the modern world.

1. Civil Engineering

Focus: Infrastructure, construction, and urban systems

Applications: Bridges, roads, buildings, dams, water systems, seismic retrofitting

Subfields: Structural, transportation, environmental, geotechnical, municipal

2. Mechanical Engineering

Focus: Machines, dynamics, thermodynamics, and materials

Applications: Engines, robotics, manufacturing equipment, HVAC systems

Subfields: Mechatronics, automotive, aerospace, acoustics, fluid mechanics

3. Electrical and Electronic Engineering

Focus: Electricity, circuits, electromagnetism, signal processing

Applications: Power grids, microchips, telecommunications, consumer electronics

Subfields: Power systems, control systems, embedded systems, RF engineering

4. Chemical Engineering

Focus: Chemical processes, materials, and industrial production

Applications: Pharmaceuticals, petrochemicals, food processing, energy storage

Subfields: Process engineering, biochemical, materials, electrochemical

5. Computer and Software Engineering

Focus: Algorithms, data structures, systems architecture, software design

Applications: Operating systems, AI, cybersecurity, web platforms, apps

Subfields: Embedded systems, machine learning, human-computer interaction, dev ops

6. Aerospace Engineering

Focus: Flight, propulsion, and vehicle dynamics in air and space

Applications: Aircraft, spacecraft, satellites, launch systems

Subfields: Aeronautical, astronautical, avionics, orbital mechanics

7. Environmental Engineering

Focus: Sustainability, resource use, and ecological resilience

Applications: Water purification, air pollution control, waste management, remediation

Subfields: Climate engineering, ecological engineering, green infrastructure

8. Biomedical and Genetic Engineering

Focus: Medical technology, biological systems, and genetic design

Applications: Prosthetics, implants, synthetic organs, bioinformatics, gene therapy

Subfields: Bioinstrumentation, tissue engineering, molecular bioengineering

9. Industrial and Systems Engineering

Focus: Efficiency, logistics, optimization, and large-scale systems integration

Applications: Supply chains, factory workflows, human factors, operations research

Subfields: Manufacturing systems, ergonomics, quality control, lean production

10. Materials Engineering

Focus: Properties and processing of materials—metals, ceramics, polymers, composites

Applications: All sectors—from nanotechnology to aerospace

Subfields: Nanomaterials, metallurgy, polymer science, smart materials

11. Nuclear Engineering

Focus: Fission and fusion systems, radiation, reactor design

Applications: Nuclear power plants, medical imaging, waste disposal, propulsion

Subfields: Reactor physics, radiological engineering, fusion systems

12. Marine and Ocean Engineering

Focus: Technologies for ocean environments

Applications: Shipbuilding, offshore oil platforms, underwater vehicles, tidal energy

Subfields: Naval architecture, subsea systems, hydrodynamics, marine robotics

13. Agricultural and Food Engineering

Focus: Mechanization and optimization of food systems and agricultural processes

Applications: Irrigation, food processing, storage, vertical farming, agritech

Subfields: Precision agriculture, biosystems engineering, food safety design

14. Emerging and Interdisciplinary Fields

- Quantum Engineering – Combining quantum mechanics with engineering applications

- Neuroengineering – Bridging neuroscience and device engineering

- Space Systems Engineering – Managing the complexity of orbital and planetary systems

- Ethical and Humanitarian Engineering – Focused on social impact and ethical design

- Cybersecurity Engineering – Defending and designing secure digital infrastructures

- Data and AI Engineering – Creating intelligent, large-scale data systems

Engineering has evolved beyond silos. Today’s most urgent problems—climate change, pandemics, infrastructure collapse, ethical AI—demand collaboration across disciplines. The engineer of the future is not only a specialist but a systems thinker, a communicator, and an ethical leader.

IX. The Future of Engineering

As humanity confronts planetary challenges and ventures beyond Earth, engineering stands at the frontier of possibility. The future of engineering will be defined not only by technological breakthroughs, but by how wisely and ethically we apply them. In this age of complexity, the role of the engineer is evolving—from specialist and builder to steward, ethicist, and visionary.

Engineering for a Sustainable Civilization

The 21st century has made clear that industrial growth must give way to ecological balance:

- Climate-resilient engineering will redesign cities, coastlines, and infrastructure to withstand rising seas, extreme weather, and resource volatility.

- Circular economy design will replace linear models of waste, ensuring products and materials are reused, remanufactured, and recycled.

- Planetary systems modeling, integrating ecology, economics, and engineering, will guide sustainable development and restoration projects.

Frontiers in Energy and Materials

- Fusion power, long the “holy grail” of energy, is now within reach thanks to advances in plasma containment and superconducting materials. If successful, it could provide near-limitless clean power.

- Graphene, metamaterials, and programmable matter may revolutionize conductivity, flexibility, and performance in all sectors—from transportation to electronics.

- Space-based solar power and wireless energy transmission could decouple energy production from terrestrial limits.

Space, Oceans, and Extreme Environments

- Interplanetary engineering will be needed for sustainable life on the Moon, Mars, and beyond: habitat systems, life support, in-situ resource utilization, and planetary protection.

- Asteroid mining and space elevators remain speculative but are under serious exploration as engineering frontiers.

- On Earth, deep-sea exploration and underwater habitats may unlock new insights into ecology, medicine, and materials science.

Biological and AI Co-Engineering

- Synthetic biology will increasingly integrate with engineering to design organisms for medicine, agriculture, and environmental restoration.

- Neuroengineering may allow direct brain-computer interfaces, enhancing memory, perception, or even shared cognition.

- Artificial intelligence systems will co-design and even co-evolve with human engineers, producing complex solutions beyond human intuition.

Democratized and Decentralized Engineering

- Open-source engineering platforms and distributed manufacturing (via 3D printing and blockchain-secured protocols) will enable communities to self-supply and self-innovate.

- Global collaboration networks, aided by AI translators and real-time simulation tools, will allow multinational, multicultural design teams to address planetary problems.

- Civic technologies will allow citizens to participate directly in the shaping of their environments, from city planning to pollution monitoring.

The Moral Imperative of Engineering

The power of engineering must be matched by ethical wisdom. The future will demand:

- Equity-driven design, addressing disparities in infrastructure, health, and access

- Engineering ethics education, making integrity and social responsibility as central as math and physics

- Planetary stewardship, integrating Indigenous knowledge, human rights, and ecological intelligence into every design decision

Engineering tomorrow will mean more than building machines—it will mean designing life systems, stewarding the planet, and uplifting humanity. To meet these goals, we must cultivate engineers not only of skill, but of wisdom, humility, and moral clarity.

X. Timeline of Engineering History

Below is a chronological timeline highlighting key periods, inventions, and figures in the global history of engineering. This is a simplified map of the vast and diverse innovations that have shaped human civilization from prehistory to the present.

Prehistoric and Ancient World

- 2.5 million BCE – First known stone tools (Oldowan industry)

- 3000 BCE – Pyramids of Egypt; development of surveying and ramp construction

- 2600 BCE – Urban planning and drainage systems in Indus Valley cities

- 2100 BCE – Ziggurats and canal systems in Mesopotamia

- 1000 BCE – Chinese cast iron production begins

- 600 BCE – Greek engineer Eupalinos builds tunnel using geometric principles

- 300 BCE – Archimedes develops mechanical principles of leverage and buoyancy

- 100 BCE – 200 CE – Roman aqueducts, roads, and concrete revolution

- 100 CE – Zhang Heng invents seismograph in Han China

Medieval and Islamic Golden Age

- 800 CE – Banu Musa brothers write Book of Ingenious Devices (automation)

- 1000 CE – Windmills and waterwheels spread across Persia and Europe

- 1206 CE – Al-Jazari publishes The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices

- 1100–1300 CE – Gothic cathedrals and flying buttresses transform European architecture

- 1320 CE – Su Song’s astronomical clock tower in China inspires mechanical design

Renaissance and Enlightenment

- 1452–1519 – Leonardo da Vinci sketches machines, hydraulics, and aircraft concepts

- 1600s – Galileo, Newton, and Hooke formulate laws of motion, stress, and gravity

- 1700s – Canal systems, surveying tools, and mechanical innovations advance infrastructure

- 1781 – James Watt patents steam engine enhancements for industry

Industrial Revolution

- 1804 – First steam locomotive (Trevithick)

- 1825–1869 – Massive rail networks built in UK, USA, and Europe

- 1856 – Bessemer process for mass-producing steel

- 1876 – Invention of the telephone (Bell); electrical engineering takes off

- 1882 – Edison opens first public electric utility in New York

- 1880s–1890s – Nikola Tesla develops AC power and induction motor

Early 20th Century

- 1903 – Wright brothers achieve first powered flight

- 1927–1931 – Empire State Building and Hoover Dam exemplify large-scale engineering

- 1930s – Control theory, feedback systems, and operations research emerge

- 1942 – First nuclear reactor (Fermi, Chicago Pile-1)

- 1945 – ENIAC, the first general-purpose digital computer

- 1957 – Sputnik I: first artificial satellite

Late 20th Century

- 1969 – Apollo 11 Moon landing

- 1971 – Intel produces first microprocessor, first personal computers arise

- 1983 – TCP/IP protocol adopted: the modern internet is born

- 1989 – Tim Berners-Lee creates the World Wide Web

- 1997 – NASA’s Pathfinder rover lands on Mars

21st Century

- 2000s – The smartphone. AI, nanotech, and genomics integrate into engineering

- 2010s – Rise of renewable energy, 3D printing, and precision medicine

- 2020s – Mars missions, quantum computing advances, smart cities expand

- Future Prospects – Fusion power, space colonization, climate restoration, ethical AI

This timeline reveals a truth echoed throughout history: engineering is both a mirror of human potential and a compass for civilization’s direction. It is a story not only of tools, but of imagination, collaboration, and responsibility.

Conclusion – Engineering the Future of Humanity

Engineering is the signature of civilization. It reflects how we shape our world—and, in turn, how that world shapes us. From the first sharpened stone to the circuits of artificial intelligence, from aqueducts and cathedrals to interplanetary rovers and genome editors, engineering is the story of human intention made manifest in matter and motion.

Across time, engineering has evolved from instinctive survival to a profession grounded in science and guided by purpose. Yet as our tools grow more powerful, the moral stakes grow higher. The engineer of the future must not only be a technician, but a visionary and a steward—responsible not only for what is built, but for whom and why.

In an era of climate crisis, global inequality, and rapid technological change, the future of engineering lies not only in invention, but in integration: integrating ethical reflection with technical expertise; integrating sustainability with innovation; and integrating global cooperation with local empowerment.

We now stand at a crossroads: Will engineering reinforce systems of exploitation and environmental harm? Or will it lead us toward a world of balance, justice, and thriving life? The answer depends not only on what we build, but on how we teach, regulate, and inspire the engineers of tomorrow.

In the Age of Intelligence, engineering must become a humanistic science—fueled by creativity, guided by ethics, and committed to the flourishing of all life.

Let this history be not just a chronicle of achievements, but a compass for the path ahead.