Table of Contents

- Introduction

Electricity, Invention, and the Engineering of Modern Life - Part I: Foundations of Electricity and Magnetism

From Natural Curiosity to Scientific Law - Part II: Birth of a Discipline

The Emergence of Electrical Engineering as a Profession - Part III: Key Innovations and Technological Milestones

Communication, Power, and the Electronic Revolution - Part IV: Branches of Electrical Engineering

Power, Control, Communication, and Computation - Part V: Applications and Industry Impact

Where Theory Becomes Technology - Part VI: Skills, Tools, and Education in Electrical Engineering

Training the Problem Solvers of the Electric Age - Part VII: The Future of Electrical Engineering

Intelligent Systems, Global Challenges, and the Next Frontier - Appendix A: Prestigious Journals and Publications

The Knowledge Infrastructure of the Field - Conclusion

Power, Precision, and Potential

Introduction

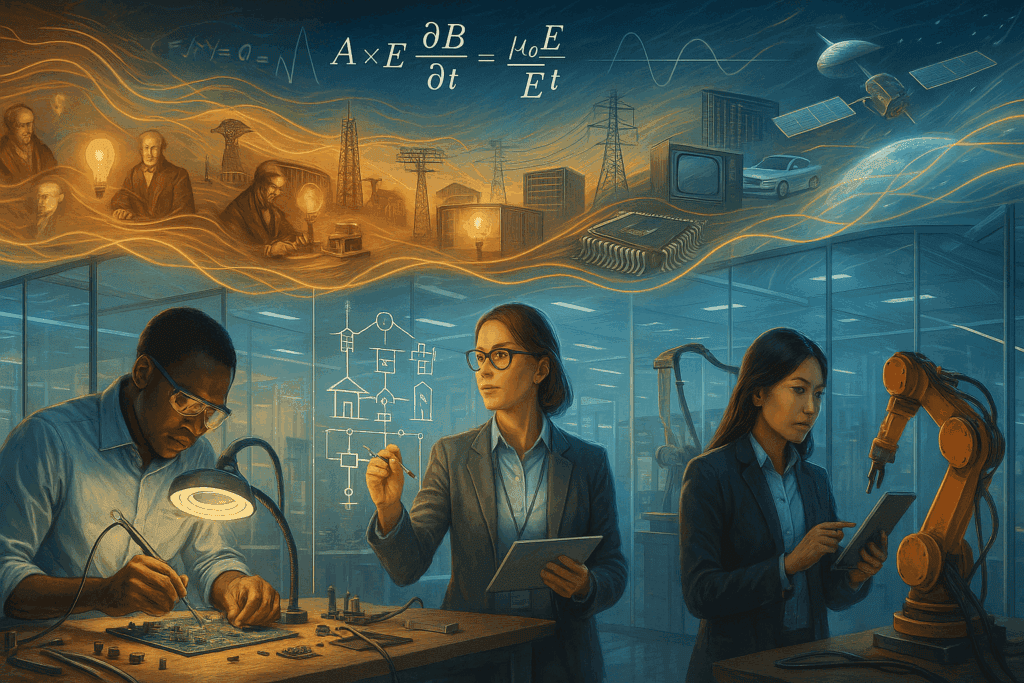

Electricity is invisible, intangible, and omnipresent—an elemental force that once seemed the domain of lightning and magic, now woven into the fabric of daily life. From the quiet hum of a refrigerator to the vast grid lighting cities, from satellites orbiting the planet to the smartphones in our hands, nearly everything modern civilization depends on exists because of one remarkable discipline: electrical engineering.

Electrical engineering is the science and art of harnessing electricity, electronics, and electromagnetism for practical use. It is a field rooted in the fundamental laws of physics, powered by mathematical precision, and expanded by waves of invention and innovation. More than a technical pursuit, electrical engineering is a central force behind the shaping of the modern world—fueling progress in energy, communication, transportation, computation, medicine, and beyond.

Its story begins with curiosity. Early thinkers puzzled over sparks and shocks, speculating on the nature of electric and magnetic forces. In time, their discoveries were formalized into scientific principles. When these principles met the industrial imagination of the 19th century, a new kind of engineering emerged—one that would build telegraphs, telephone lines, power grids, and radio towers, and later, satellites, robots, and integrated circuits.

Electrical engineering formally emerged as a distinct academic and professional field in the late 1800s. Within decades, it had fractured into powerful subfields: power systems, control systems, telecommunications, signal processing, electronics, and more. Each has grown into a global enterprise of research, development, and applied design, touching nearly every industry and public service.

This article explores the deep history, scientific principles, and technological revolutions of electrical engineering. It traces the field from its earliest conceptual foundations to its vital role in contemporary life, and looks ahead to the challenges and frontiers that define its future. Along the way, it highlights key figures, landmark inventions, core ideas, and the many ways electrical engineering continues to electrify—and illuminate—our world.

Part I: Foundations of Electricity and Magnetism

Before electrical engineering became a profession, before the word “electronics” was coined, there was awe. The ancient Greeks noticed that rubbed amber attracted feathers. In the 1600s, William Gilbert coined the term electricus to describe that force. What began as natural philosophy would, over two centuries, transform into a rigorous science—and eventually into a technological revolution.

1.1 Early Explorations and Scientific Breakthroughs

By the 18th century, experimenters began to demystify electricity through bold (and often painful) experimentation. In 1752, Benjamin Franklin famously flew a kite in a thunderstorm, proving that lightning was a form of electricity. Around the same time, the Leyden jar—a primitive capacitor—allowed researchers to store and discharge electrical energy, opening the door to systematic study.

In the decades that followed, several European scientists laid the foundation for a future discipline:

- Alessandro Volta (Italy) created the first chemical battery in 1800, known as the voltaic pile. It provided the first steady source of electric current and helped shift electricity from a curiosity to a tool.

- Hans Christian Ørsted (Denmark) discovered in 1820 that electric current generates a magnetic field, revealing a deep link between electricity and magnetism.

- André-Marie Ampère (France) expanded on Ørsted’s work and formulated mathematical laws of electromagnetism.

- Michael Faraday (England) demonstrated electromagnetic induction in 1831—the principle that makes electric generators and transformers possible. Faraday’s insights remain central to every power plant on Earth.

- Georg Simon Ohm (Germany) described the relationship between voltage, current, and resistance, now immortalized as Ohm’s Law.

These discoveries shaped the early science of electromagnetism. Yet it wasn’t until 1864 that a true unification occurred.

1.2 Maxwell’s Equations and the Birth of Electromagnetic Theory

James Clerk Maxwell, a Scottish physicist and mathematician, synthesized decades of experimental work into a theoretical framework. His Maxwell’s equations—a set of four elegant differential equations—described how electric and magnetic fields are generated and altered by each other and by charges and currents. These equations not only predicted the existence of electromagnetic waves but also showed that light itself was an electromagnetic phenomenon.

Maxwell’s work marked a turning point. With a theoretical structure in place, engineers could now design systems to harness these forces in predictable ways. The invisible was no longer unknowable.

This deep scientific groundwork set the stage for practical innovation. Within a generation, inventors would wire the world with telegraphs, lightbulbs, and motors—and electrical engineering would be born.

Part II: Birth of a Discipline

As the 19th century drew to a close, the world stood on the threshold of a new technological age. Electricity—once a mystery of science—had become a tool of power, communication, and imagination. The practical applications of electromagnetism were no longer confined to laboratories; they were reshaping cities, economies, and societies. But with this rapid expansion came a new need: trained experts who could design, build, and manage increasingly complex electrical systems. Thus, electrical engineering was born—not merely as a set of techniques, but as a formal discipline.

2.1 The Telegraph and the First Electrical Systems

The practical era of electrical engineering began with the telegraph. In 1837, Samuel Morse and Alfred Vail introduced a device that could send coded electrical pulses over long distances. Telegraphy soon connected continents and revolutionized communication, making it the first major industry dependent on electrical technology.

Its success created a new kind of technician—someone who understood both the science and the systems. Lines needed to be laid, signals boosted, and equipment maintained. This called for more than just empirical knowledge; it required a new kind of engineer.

2.2 Electrification and the Rise of Infrastructure

The invention of the electric light bulb by Thomas Edison in 1879 and the subsequent establishment of centralized power stations in the 1880s marked the second wave of electrical innovation. Edison’s Pearl Street Station in New York began providing direct current (DC) power in 1882. Around the same time, Nikola Tesla, in partnership with George Westinghouse, developed and promoted alternating current (AC) power systems, which proved more efficient for long-distance transmission.

The resulting “War of the Currents” between Edison’s DC and Tesla’s AC systems captured public attention and spurred investment in infrastructure, transforming electricity from a marvel into a utility.

By the late 1880s, cities across Europe and North America were being wired for electricity. New careers, new industries, and new institutions emerged to manage this electrical transformation.

2.3 Academic and Institutional Foundations

The rise of electrical engineering as a distinct academic field happened rapidly in response to industrial demand:

- 1882: The Technische Universität Darmstadt in Germany established the first electrical engineering faculty.

- 1883–1885: Cornell University and University College London (UCL) introduced electrical engineering courses and departments in the U.S. and U.K., respectively.

- 1884: The American Institute of Electrical Engineers (AIEE) was founded to promote collaboration, research, and professional standards. It would later merge with the Institute of Radio Engineers (IRE) to form today’s IEEE—the world’s largest technical professional organization.

- Electrical engineering departments soon spread to leading institutions, formalizing what had once been the work of inventors and hobbyists.

2.4 A New Kind of Engineer

These early electrical engineers were more than scientists—they were builders of the future. Trained in mathematics and physics, but equally adept at practical design, they created new networks of power, light, and information. Their work gave rise to entire industries: electric utilities, manufacturing, telecommunications, and eventually electronics.

By the dawn of the 20th century, electrical engineering was no longer an emerging curiosity. It was a cornerstone of modern civilization—one that would continue to grow, diversify, and transform with each new discovery.

Part III: Key Innovations and Technological Milestones

The history of electrical engineering is marked by sudden leaps—moments when ideas became machines, and machines transformed society. These breakthroughs didn’t just improve upon existing technologies; they created entirely new ways of living, working, and thinking. This section explores the major technological milestones that pushed electrical engineering from theory and infrastructure into the digital, electronic, and wireless age.

3.1 The Age of Communication

The desire to transmit messages over long distances has driven much of electrical engineering’s evolution.

- The Telegraph (1837): Samuel Morse’s invention of the electrical telegraph laid the groundwork for global communication networks. Morse code, a simple series of on-off electrical pulses, became the first digital language in history.

- The Telephone (1876): Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone transformed communication from encoded pulses into the transmission of the human voice. It sparked the first large-scale electrical network—millions of miles of copper wire crisscrossing nations.

- Wireless Communication: In the 1890s, Guglielmo Marconi demonstrated wireless telegraphy, using radio waves to send messages without wires. His success enabled the birth of broadcast radio, military communication, and eventually, the entire wireless revolution.

These inventions not only changed society—they demanded new tools, components, and theories, spurring the development of signal processing, modulation techniques, and transmission line theory.

3.2 Electrification and the Power Revolution

The late 19th century witnessed the electrification of the world:

- Electric Light and Power (1879 onward): Edison’s incandescent bulb became the symbol of modernity. To make it practical, centralized power generation and distribution systems were created, including hydroelectric dams and fossil-fuel plants.

- AC vs. DC: The War of the Currents between Edison’s DC systems and Tesla’s AC innovation resulted in the triumph of AC power, now the global standard. Tesla’s polyphase AC motor, coupled with Westinghouse’s transformers, enabled efficient transmission across long distances.

- Electric Motors and Generators: Building on Faraday’s principles, rotating machines became the backbone of modern industry—from factory machinery to train engines.

These systems gave rise to power engineering: a subfield of electrical engineering focused entirely on generation, transmission, distribution, and energy efficiency.

3.3 The Electronic Revolution

The 20th century ushered in an age of miniaturization and speed, where electricity was no longer just about power—but about information.

- Vacuum Tubes: Developed in the early 1900s, vacuum tubes allowed engineers to amplify and switch electrical signals, enabling radios, early computers, and radar during World War II.

- The Transistor (1947): Invented by John Bardeen, William Shockley, and Walter Brattain at Bell Labs, the transistor replaced vacuum tubes with smaller, more efficient, and far more durable components. It launched the era of solid-state electronics.

- Integrated Circuits (1958 onward): Engineers like Jack Kilby and Robert Noyce pioneered ICs, combining multiple transistors and components onto a single chip. This enabled the creation of microprocessors and the rise of computing.

- The Digital Age: From the first calculators and mainframes to personal computers and smartphones, electronics engineering grew into its own vast domain—intertwined with computer science, materials science, and systems engineering.

Each of these milestones expanded not just what electrical engineers could do, but what society would come to expect from technology: more speed, more control, more connection.

Part IV: Branches of Electrical Engineering

As the scope of electricity expanded—from powering lights to transmitting data, from factory automation to satellite navigation—the field of electrical engineering branched into specialized domains. These subfields reflect the incredible versatility of electromagnetism and the many forms it takes in the modern world. Each branch builds on shared scientific foundations but applies them in distinct and evolving ways.

4.1 Power Systems

Power systems engineering is the oldest and most foundational branch. It focuses on the generation, transmission, and distribution of electrical power. Key areas include:

- Power Plants: Design and operation of thermal, hydroelectric, nuclear, and renewable energy sources.

- Transmission Networks: High-voltage lines and transformers that move electricity across long distances.

- Distribution Systems: Urban and rural infrastructure that delivers electricity to homes, businesses, and factories.

- Smart Grids: Digital systems that monitor and optimize energy use, integrating solar panels, wind farms, and battery storage into traditional grids.

As global energy demands rise and climate concerns deepen, power systems engineers play a vital role in developing sustainable and efficient solutions.

4.2 Electronics and Embedded Systems

Electronics engineering focuses on designing and building circuits that control electrical energy in small, precise ways. This includes:

- Analog and Digital Circuits: Using components like resistors, capacitors, transistors, and integrated circuits.

- Embedded Systems: Microcontrollers and specialized processors embedded in everything from washing machines to spacecraft.

- Consumer Devices: Smartphones, wearables, audio systems, and home automation technologies.

Modern electronics blends seamlessly with software, requiring engineers to understand both physical hardware and code.

4.3 Control Systems

Control engineering is the science of automation. It focuses on designing systems that maintain or change the behavior of other systems through feedback:

- Robotics and Mechatronics: Systems that combine sensors, actuators, and algorithms to perform tasks with precision.

- Industrial Automation: Factory machines, conveyor belts, and process control systems.

- Aerospace and Automotive Control: Aircraft stabilization, cruise control, and electric vehicle systems.

- Biological and Environmental Applications: Automated climate control, prosthetics, and smart irrigation.

Control engineers ensure that complex systems behave safely, efficiently, and predictably under changing conditions.

4.4 Telecommunications

Telecommunications engineers enable the transmission of information over distance. This rapidly evolving field includes:

- Wired Networks: Fiber optics, coaxial cable, and Ethernet infrastructure.

- Wireless Systems: Wi-Fi, cellular (3G–5G), satellite, and microwave communications.

- Antennas and Wave Propagation: Designing devices to send and receive radio signals effectively.

- Protocols and Compression: Ensuring that voice, video, and data are encoded, transmitted, and decoded efficiently.

With global connectivity now considered a basic utility, telecommunications engineering supports the internet, streaming, mobile networks, and remote work.

4.5 Signal Processing

Signal processing involves the analysis and transformation of signals—anything that can carry information, from electrical voltages to digital files.

- Audio and Speech Processing: Noise cancellation, voice recognition, and hearing aids.

- Image and Video Processing: Compression standards (like JPEG or MPEG), computer vision, and medical imaging.

- Sensor Networks: Interpreting signals from biological, environmental, or mechanical sensors.

- Mathematical Techniques: Fourier transforms, filtering, and statistical analysis to clean and enhance data.

Signal processing bridges hardware and data science—turning raw inputs into usable information.

Each of these branches is both a deep field of study and a practical toolkit. In modern practice, they often overlap—telecommunications relies on signal processing; robotics blends control systems and embedded electronics; and every branch is powered, quite literally, by power systems engineering.

Part V: Applications and Industry Impact

Electrical engineering doesn’t merely operate behind the scenes—it defines the scene. From the phones in our hands to the grids that power entire cities, electrical engineers design the systems that make 21st-century life possible. Their work reaches across sectors, industries, and continents, transforming raw energy into usable tools and turning abstract theory into real-world impact.

5.1 Key Sectors and Contributions

Electronics and Consumer Technology

Electrical engineers design the internal circuits and logic that make modern digital devices function:

- Smartphones and Computers: Miniaturized chips, touchscreen interfaces, and battery management.

- Wearables and IoT Devices: Smartwatches, fitness trackers, home assistants, and connected appliances.

- Entertainment Systems: High-definition displays, gaming hardware, and immersive audio experiences.

Power and Energy

From traditional energy to emerging technologies, electrical engineers power the world:

- Electric Utilities: Grid design, load balancing, blackout prevention, and power restoration.

- Renewable Energy: Solar panel systems, wind turbine control, energy storage solutions.

- Smart Energy Systems: Building management, smart meters, and energy efficiency in homes and industries.

Transportation

Modern transportation systems rely heavily on electrical engineering:

- Electric Vehicles (EVs): Battery systems, motor controllers, regenerative braking.

- Aviation and Aerospace: Avionics, flight control systems, and satellite technologies.

- Public Transport and Traffic: Automated train controls, intelligent traffic lights, and electrified rail systems.

Healthcare and Medical Technology

Electrical engineering advances diagnostics and patient care:

- Medical Imaging: MRI, X-ray, ultrasound, and CT technologies.

- Monitoring Equipment: ECG, EEG, pulse oximeters, and wearable health sensors.

- Therapeutic Devices: Pacemakers, infusion pumps, neural stimulators.

Robotics and Automation

Industrial and personal robots depend on the precise control systems designed by electrical engineers:

- Manufacturing Robots: Precision welding, assembly, quality control.

- Service Robots: Hospital assistants, warehouse automation, delivery drones.

- Human-Robot Interaction: Sensors, AI integration, and machine learning applications.

Telecommunications and Networking

The digital age runs on the infrastructure built by electrical engineers:

- Internet Backbone: Optical fiber networks, switching systems, routers.

- Wireless Infrastructure: Cell towers, 5G networks, satellite communication.

- Media Transmission: Streaming, real-time communication, and virtual conferencing.

5.2 Major Companies and Industry Leaders

Across every domain, electrical engineering underpins some of the world’s most influential companies:

Global Tech Giants

- Siemens – Industrial automation, power systems, medical equipment

- General Electric (GE) – Grid technology, aviation electronics, renewables

- Schneider Electric – Energy management and industrial control

- ABB – Robotics, electrification, and smart cities

Semiconductor and Chip Makers

- Intel, AMD, TSMC, NVIDIA, Texas Instruments – Design and manufacture of microprocessors and digital systems

Telecommunications and Networks

- Ericsson, Nokia, Qualcomm, Huawei, Cisco Systems – Wireless infrastructure, modems, protocols, and routers

Energy and Automotive

- Tesla – EV electronics, battery management, energy grids

- Hitachi Energy, Mitsubishi Electric, Panasonic – High-voltage equipment, clean energy systems, consumer devices

These companies are not just employers—they are hubs of innovation, shaping the global economy and technological landscape through electrical engineering.

Part VI: Skills, Tools, and Education in Electrical Engineering

Electrical engineering is a uniquely interdisciplinary field—combining abstract science, hands-on design, and systems thinking. To succeed in this fast-evolving profession, engineers need not only technical mastery but also adaptability, communication skills, and creative problem-solving. This section outlines the key competencies, tools, and educational pathways that shape the modern electrical engineer.

6.1 Core Skills of an Electrical Engineer

Technical Knowledge

At its core, electrical engineering requires fluency in:

- Physics: Especially electromagnetism, optics, and semiconductor theory

- Mathematics: Linear algebra, differential equations, complex numbers, and probability

- Circuit Theory: Analysis of linear and nonlinear circuits, frequency response, feedback systems

Problem-Solving and Analytical Thinking

Engineers must:

- Model and predict system behavior under constraints

- Analyze real-world problems to find optimized solutions

- Innovate in response to evolving technical challenges

Design and Simulation Skills

Modern engineering relies heavily on software tools:

- SPICE for circuit simulation

- MATLAB/Simulink for control systems and signal processing

- EDA (Electronic Design Automation) tools like Altium, Cadence, and Mentor Graphics for PCB layout and IC design

- FPGA design environments like VHDL and Verilog

Software and Programming

Many roles require programming skills in:

- C/C++ and Python (embedded systems, automation, scripting)

- MATLAB (data analysis, signal processing)

- Java, Rust, or HDL (hardware design and simulation)

Communication and Collaboration

Electrical engineers often work in interdisciplinary teams. Success depends on the ability to:

- Communicate complex technical ideas clearly

- Collaborate with specialists in software, mechanical design, project management, and client services

- Write technical documentation, specifications, and grant proposals

6.2 Education and Career Pathways

Undergraduate Education

A bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering typically includes:

- Core courses: Circuits, systems, electromagnetics, digital logic, electronics

- Labs and hands-on projects

- Capstone design projects or internships

Top programs worldwide include:

- MIT, Stanford, UC Berkeley (USA)

- ETH Zurich (Switzerland), TU Munich (Germany)

- Tsinghua University (China), University of Tokyo (Japan)

- Imperial College London, Cambridge, and Oxford (UK)

Graduate Study and Research

Many engineers pursue master’s or PhD degrees to specialize in areas like:

- Signal processing

- Biomedical electronics

- Power systems and renewables

- Quantum electronics and nanotechnology

Graduate education is also vital for careers in R&D, teaching, or policy development.

Professional Licensing and Certification

- In many countries, electrical engineers can become licensed professional engineers (PE) or chartered engineers (CEng).

- Certification bodies include IEEE, IET, ABET, and various national engineering councils.

- Continuing education is often required to maintain credentials and stay current with technological change.

Career Pathways

Electrical engineers may become:

- Design Engineers, Systems Engineers, Test Engineers

- Project Managers, Consultants, Technical Specialists

- Entrepreneurs, Professors, Inventors, or CTOs

Their career trajectory is often shaped by a balance of expertise, creativity, and the ability to evolve with new tools and trends.

Part VII: The Future of Electrical Engineering

Electrical engineering has always been a forward-looking field. From the first spark-gap transmitters to today’s smart grids and microchips, it evolves in step with scientific discovery and social need. As we enter a new era of interconnected systems, sustainable development, and intelligent machines, electrical engineering stands at the center of nearly every major transformation on the horizon.

7.1 Emerging Trends

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Integration

Electrical engineers are increasingly embedding machine learning into traditional systems:

- Smart sensors that adapt to context

- Predictive maintenance for electrical grids and motors

- Adaptive control systems in robotics, automotive, and aerospace

- AI-enhanced signal processing in telecommunications and medicine

Quantum and Nanoelectronics

With classical microelectronics nearing physical limits, engineers are exploring:

- Quantum computing using qubits for vast processing power

- Molecular and nanoscale devices for next-gen transistors and memory

- Neuromorphic engineering, designing circuits that mimic brain behavior

Wireless Power and Energy Harvesting

Emerging methods of delivering power without wires or batteries include:

- Inductive and resonant magnetic coupling (used in phone chargers and EV pads)

- Ambient energy harvesting from RF, heat, or motion

- Power beaming using microwave or laser transmission

Flexible and Wearable Electronics

Soft, stretchable circuits are enabling a new class of devices:

- Electronic skins for health monitoring

- Foldable displays and smart clothing

- Implantable or biodegradable medical devices

Decentralized and Sustainable Energy Systems

Engineers are reimagining energy infrastructure to meet environmental demands:

- Microgrids and community solar networks

- Vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technologies

- Advanced battery systems and real-time load balancing

7.2 Global Challenges and Opportunities

Sustainability and Climate Action

Electrical engineers are vital in the fight against climate change:

- Electrification of transportation and industry

- Expansion of clean energy and carbon-free grids

- Climate modeling through high-performance computing

Universal Access and Equity

Bringing electricity and connectivity to underserved regions is a 21st-century imperative:

- Low-cost solar systems and micro-inverters

- Satellite-based internet infrastructure

- Open-source hardware for education and development

Security and Resilience

As infrastructure becomes smarter, it also becomes more vulnerable:

- Cybersecurity for power grids, autonomous vehicles, and medical devices

- EMP and disaster-resilient systems

- Redundancy and fail-safe design for critical services

Human-Centered Engineering

Tomorrow’s engineers must consider not only technical success, but human outcomes:

- Ethics of automation and AI

- Accessibility in design

- Cross-cultural collaboration in global development

Electrical engineering, once the domain of sparks and wires, now spans data, biology, artificial intelligence, and planetary systems. As we look to a future defined by intelligent infrastructure, sustainable energy, and global interconnection, the field will remain essential—not only for what it builds, but for how it helps humanity adapt, evolve, and thrive.

Appendix A: Prestigious Journals and Publications in Electrical Engineering

For researchers, practitioners, and students alike, staying current with cutting-edge developments in electrical engineering requires access to top-tier academic and professional publications. These journals provide peer-reviewed research, technical innovations, reviews, and standards that shape the future of the field. Chief among them is the IEEE—the world’s largest technical professional organization—whose publications span nearly every domain of electrical and electronic engineering.

A.1 IEEE Publications and Transactions

The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) publishes hundreds of specialized journals and magazines. Some of the most respected include:

Flagship Journals

- IEEE Transactions on Power Systems – Advanced research on electrical power generation and distribution

- IEEE Transactions on Communications – Core developments in wireless and network communication systems

- IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics – Focused on applications in automation, robotics, and industrial control

- IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing – Foundational research in signal theory, filtering, and transformations

- IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid – Innovations in grid intelligence, energy management, and distributed power

- IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering – Electrical engineering applications in medical and healthcare fields

- IEEE Transactions on Robotics – Leading research in autonomous systems and machine control

- IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications – Research in mobile, satellite, and short-range communication

- IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits – Microelectronics, CMOS design, and device modeling

- IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices – Emerging devices, semiconductors, and nanoelectronic technologies

General and Interdisciplinary Publications

- IEEE Spectrum – The IEEE’s magazine for general audiences, covering technology trends and public issues

- IEEE Access – Open-access, multidisciplinary journal with broad coverage of engineering and technology

- Proceedings of the IEEE – High-impact surveys and reviews from leading engineers and scientists

A complete list of IEEE journals and transactions is available at:

👉 https://www.ieee.org/publications/index.html

A.2 Other Prestigious Engineering Journals

Nature Electronics

- Published by Nature, this high-impact journal covers foundational and applied research in electronic and electrical systems—including semiconductors, photonics, sensors, and circuit design.

👉 https://www.nature.com/natelectron/

IET (Institution of Engineering and Technology) Journals

- Electronics Letters

- IET Power Electronics

- IET Control Theory & Applications

- IET Renewable Power Generation

These journals serve as leading platforms in the UK and Commonwealth countries for innovative engineering research.

Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering (Hindawi)

- Peer-reviewed and open access, covering hardware and software integration, embedded systems, and intelligent networks.

Sensors and Actuators A/B (Elsevier)

- Core publications in sensor technology, microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), and signal interfacing.

Together, these publications represent the intellectual infrastructure of electrical engineering—a reflection of its vast reach and its constant motion. They are where today’s experiments become tomorrow’s standards.

Conclusion

Electrical engineering is more than just the study of circuits and signals—it is the architecture of modern life. Born from the fusion of scientific curiosity and industrial ambition, it has grown into one of the most vital and far-reaching disciplines in human history. From the silent current flowing through our walls to the satellite signals beaming across the sky, electrical engineering is the invisible engine behind the global economy, digital society, and future civilization.

Its history is a chronicle of discovery: from Franklin’s kite to Faraday’s coil, from Edison’s bulbs to Tesla’s motors, from vacuum tubes to transistors, microchips, and quantum circuits. Its practitioners—engineers, inventors, scientists—have not only built machines but created entirely new ways of connecting, powering, and understanding the world.

Today, electrical engineering is at the frontier of global challenges: climate resilience, clean energy, digital equity, artificial intelligence, and intelligent infrastructure. It is not a static profession, but a living, evolving ecosystem of knowledge and application. It trains minds to think in systems, build with precision, and solve with creativity.

As we move into a century defined by sustainability, intelligence, and interdependence, electrical engineering will continue to illuminate the path forward—quite literally lighting the way. It is a discipline not only of power and precision, but of potential: a field where the invisible becomes visible, and the theoretical becomes transformative.