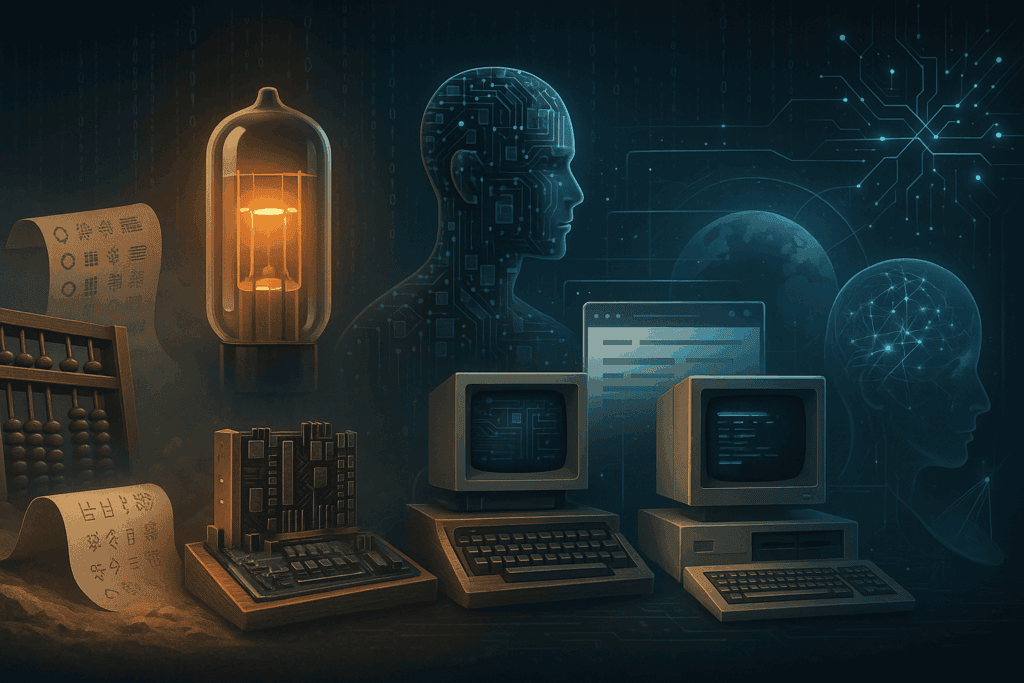

1. Introduction: Machines That Think

The human drive to compute—how it began, what it became, and why it matters.

2. Counting Beyond the Mind: Ancient and Mechanical Origins

From the abacus to Babbage—early inventions that laid the foundation for computation.

3. Engines of Logic: The Birth of Computational Theory

Turing, Lovelace, and the math that made machine intelligence possible.

4. War and Innovation: The Electronic Dawn

ENIAC, Manchester Baby, and the secret history of codebreaking and computing.

5. Shrinking the Machine: From Tubes to Transistors

How microchips miniaturized the future and launched Moore’s Law.

6. The Personal Computing Revolution

Garage startups, command lines, GUIs, and the rise of Apple, IBM, and Microsoft.

7. The Networked World: The Internet Changes Everything

ARPANET to broadband—how the web rewired human connection and culture.

8. The Science of Computer Science

Algorithms, data structures, AI, and the disciplines behind the digital universe.

9. Building a Computer: Anatomy of a Thinking Machine

A hands-on breakdown of modern hardware—and what makes it tick.

10. Programming Languages: Teaching the Machine to Think

From C to Python to Rust—how code evolved, and what it tells machines to do.

11. Website Building and Web Design

Pixels, structure, and UX—how we design the digital spaces we now live in.

12. The Future of Computing: Beyond Silicon, Beyond Human

Quantum leaps, neural nets, ethics, and the emerging Age of Intelligence.

1. Introduction: Machines That Think

Before smartphones, before servers, before semiconductors—there were gears, levers, and dreams. Humans have always needed to compute. Whether it was tallying grain, mapping the stars, or breaking wartime codes, the desire to offload mental effort onto machines is as old as civilization itself.

But the real story begins when those machines started to become something more. Not just faster calculators, but logical engines. Pattern hunters. Memory keepers. And eventually—thinking systems.

The modern computer didn’t emerge in one clean burst. It came from a chain reaction of ideas: ancient tools like the abacus, mechanical marvels from Leibniz and Babbage, the pure math of Turing, the industrial genius of IBM, the garage grit of Apple. Along the way, we learned to speak to machines in languages they could parse—binary, assembly, Python—and built networks that now loop the globe with real-time information.

This is the story of how humanity learned to compute—how we shaped the machine, and how it began to shape us. It’s about the science behind the screens, the quiet revolutions in logic and silicon, and the minds that made it all happen.

Let’s rewind. Before AI. Before cloud. Before code. Let’s trace the logic path back to its source.

2. Ancient and Early Mechanical Devices: Counting Beyond the Mind

Long before algorithms lived in the cloud, computation was tactile. It was fingers on beads, gears grinding numbers, and hand-cranked machines that mimicked thought.

The Abacus—humanity’s first mass-market calculator—was born in ancient Sumer and went viral across China, Greece, and Rome. It didn’t run code, but it did run empires. For millennia, it was the go-to tool for merchants and mathematicians trying to bring order to quantity.

Then came the tinkerers. In 1623, German polymath Wilhelm Schickard built a contraption that could add and subtract automatically. A few decades later, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz—yes, the calculus guy—leveled up with a stepped drum machine that handled all four operations. More importantly, he laid out a new philosophy: that math, logic, and computation were all part of the same system. He even pitched binary before it was cool.

Meanwhile, in France, Joseph Marie Jacquard wasn’t thinking about numbers. He was trying to automate weaving. His breakthrough? Punched cards that controlled looms—hard-coded textile patterns, no programmer required. The idea of feeding instructions into a machine stuck. A century later, it would come back in a big way.

That century belonged to Charles Babbage, a Victorian visionary who hated human error and loved precision gears. He dreamed up the Analytical Engine, a steam-powered general-purpose computer complete with memory, loops, and conditional branching—features still fundamental to computing today. Though the machine was never fully built, the architecture was there: input, processing, storage, output. If your laptop had a great-great-grandparent, this was it.

By his side was Ada Lovelace, who saw beyond the math. She imagined machines composing music and manipulating symbols—concepts that now live in AI art generators and language models. She wrote what many call the first algorithm. She also predicted that computers could do more than crunch numbers—they could reflect the human mind.

These early devices weren’t digital, but they were decisive. They turned raw ideas into mechanisms, laid the conceptual framework, and proved one thing: humans were ready to outsource thinking.

3. The Birth of Computational Theory: Engines of Logic

Hardware gets the glory. But without theory, it’s just metal.

By the mid-19th century, engineers had mechanical computing on their minds. But the 20th century? That’s when logic itself got hacked. The biggest breakthroughs weren’t machines—they were ideas that told us what a machine could do.

Enter Alan Turing, the British mathematician who essentially cracked open the brain of the future. In 1936, he published a paper outlining a purely theoretical construct: the Turing machine. It wasn’t real hardware. It was a thought experiment—a kind of imaginary computer that could read and write symbols on an infinite strip of tape, following a set of rules. Sounds abstract? It was. But it laid the foundation for everything your smartphone does.

The Turing machine proved a key concept: any problem that can be algorithmically solved can be computed by a machine with a simple set of instructions. Boom—computation became a universe, and logic became executable.

Turing’s genius didn’t stop at theory. During World War II, he put his ideas to work at Bletchley Park, leading a team that built electromechanical bombes to crack the Nazi Enigma code. That moment wasn’t just about winning the war. It was the beginning of computation as a weapon—and a world-changing tool.

But Turing wasn’t alone in reimagining logic. Mathematicians like Alonzo Church, Kurt Gödel, and John von Neumann were simultaneously rewriting what it meant to think in systems. They weren’t building computers—they were building the language of computers: logical operations, stored programs, abstract data.

Back in the 1800s, Ada Lovelace had glimpsed this future. She saw that computation wasn’t just arithmetic—it was symbolic, creative, even artistic. Now, a century later, her vision was taking shape. Logic gates. Loops. Conditions. Functions. All the conceptual guts of modern programming were suddenly in the air.

This was the moment when computers stopped being mechanical curiosities and started becoming theoretical inevitabilities.

Next came the real machines—and they would change everything.

4. War and Innovation: The Electronic Dawn

If necessity is the mother of invention, war is its overcaffeinated startup accelerator.

In the 1940s, computation left the lab and entered the war room. And fast. The goal wasn’t academic. It was tactical: crack codes, fire artillery, and calculate at speeds no human could match. The result? The birth of electronic computing.

Let’s start with ENIAC. Built in secret at the University of Pennsylvania and unveiled in 1945, the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer was a beast: 30 tons, 17,000 vacuum tubes, and more blinking lights than a Vegas casino. But under the hood, it was pure breakthrough—a general-purpose, programmable, digital computer. It could run complex calculations in minutes that would’ve taken teams of people days. For the first time, electrons moved faster than thought.

But ENIAC had a catch: it wasn’t a stored-program computer. You had to rewire it manually to change what it did. That innovation came a few years later, across the Atlantic.

The Manchester Baby—officially, the Small-Scale Experimental Machine—ran its first program in 1948. It was small, ugly, and beautiful. Why? It introduced something game-changing: the stored program. Instructions and data lived in memory side by side, ready to be read and rewritten at machine speed. It’s the blueprint every modern computer still uses.

Hovering above it all was Alan Turing, whose wartime heroics and theoretical work made him the unofficial architect of modern computing. While others built the hardware, Turing had already built the mind behind it. His postwar work at the University of Manchester helped usher in programmable machines—and the eerie early ideas of artificial intelligence.

This era wasn’t just about machines. It was about redefining what machines could be. Vacuum tubes gave computers their first breath of speed. Logic circuits made them obey. And humans—under pressure, in code-cracking labs and defense departments—saw just how far this thing could go.

The digital age didn’t begin in Silicon Valley. It began in bunkers and physics labs, where math met metal and intelligence became silicon.

5. From Vacuum Tubes to Transistors: Shrinking the Machine

The earliest computers were massive, hot, and fragile—like trying to run your smartphone on lightbulbs and prayer. The problem? Vacuum tubes. Sure, they could switch and amplify signals, but they were clunky, power-hungry, and exploded if you sneezed too hard. If computing was going to scale, it needed a new core.

Enter the transistor.

In 1947, at Bell Labs, a trio of scientists—John Bardeen, William Shockley, and Walter Brattain—cracked it. The transistor was a tiny solid-state switch that could do everything a vacuum tube did, only faster, cooler, cheaper, and smaller. It didn’t just upgrade computing—it redefined it. This wasn’t just a component. It was a pivot point. And it won them the Nobel Prize.

Suddenly, the future shrank.

By the late 1950s, transistors were everywhere—from mainframes to military tech. But even they had their limits. Wiring thousands of discrete transistors by hand? Nightmare. What came next was pure magic: the integrated circuit.

Developed independently by Jack Kilby at Texas Instruments and Robert Noyce at Fairchild Semiconductor, the integrated circuit—aka the microchip—packed multiple transistors onto a single piece of silicon. Think of it as a miniature city of logic, built in layers. It slashed size, boosted reliability, and launched Moore’s Law into motion: the number of transistors on a chip would double roughly every two years. And for a while, it did.

Meanwhile, IBM was dominating the scene with its System/360 mainframes, while university researchers and military labs kept pushing the limits of what machines could do. In the background, Silicon Valley was quietly emerging—not just as a place, but as a mindset: fast, lean, iterative.

Computers were still expensive, still big, still mostly tools for governments, banks, and universities. But they were starting to feel… personal.

The hardware revolution wasn’t just about making machines faster. It was about making them fit in a room. Then on a desk. Then on your lap. And eventually, in your pocket.

It all started with a few microscopic switches etched in silicon—and a very big idea: what if you could think at the speed of electricity?

6. The Personal Computing Revolution

By the 1970s, computers had already been to the moon. But back on Earth, most people had never touched one. That was about to change.

The personal computer didn’t arrive with a bang—it booted up in garages, basements, and labs, one blinking cursor at a time. The ingredients were all there: microchips, ambition, counterculture ethos, and the sweet, sweet taste of autonomy.

In 1975, the Altair 8800 hit the cover of Popular Electronics. It looked like a sci-fi toaster but sparked something big: the idea that computing power didn’t have to live in government basements—it could live in your bedroom. Enter the hackers, hobbyists, and future billionaires.

That same year, a college dropout named Bill Gates and his friend Paul Allen wrote a BASIC interpreter for the Altair. They would go on to build Microsoft.

Meanwhile in California, another dropout—Steve Jobs—teamed up with Steve Wozniak, a wizard with circuits. They launched the Apple I in 1976, assembled on Jobs’ garage floor. The Apple II followed in ’77 and made computers sleek, colorful, and friendly. It was a machine you could fall in love with.

By the 1980s, IBM—the Big Blue titan—dropped the IBM PC, standardizing a new era of compatible personal computing. Microsoft provided the OS: MS-DOS, a command-line jungle that would eventually evolve into Windows. Clunky, yes. But universal.

Then came the GUI—graphical user interfaces. No more blinking prompts and mystery commands. Apple’s Macintosh, launched in 1984 with that iconic Orwellian ad, brought the mouse, windows, and WYSIWYG into the mainstream. It was computing with visual flair and intuitive vibes.

As prices dropped and performance climbed, computers invaded homes, offices, and schools. Word processors killed the typewriter. Spreadsheets revolutionized accounting. Kids played Oregon Trail. Parents learned to fear the blue screen of death.

Underneath it all, Moore’s Law kept ticking. Every couple of years, chips got denser, faster, and cheaper. Every upgrade brought more memory, better graphics, and—eventually—multimedia, sound, and the internet.

By the end of the ’90s, personal computing wasn’t a novelty. It was culture. Identity. Power.

Computers were no longer just tools. They were portals—into games, work, ideas, and soon, the world.

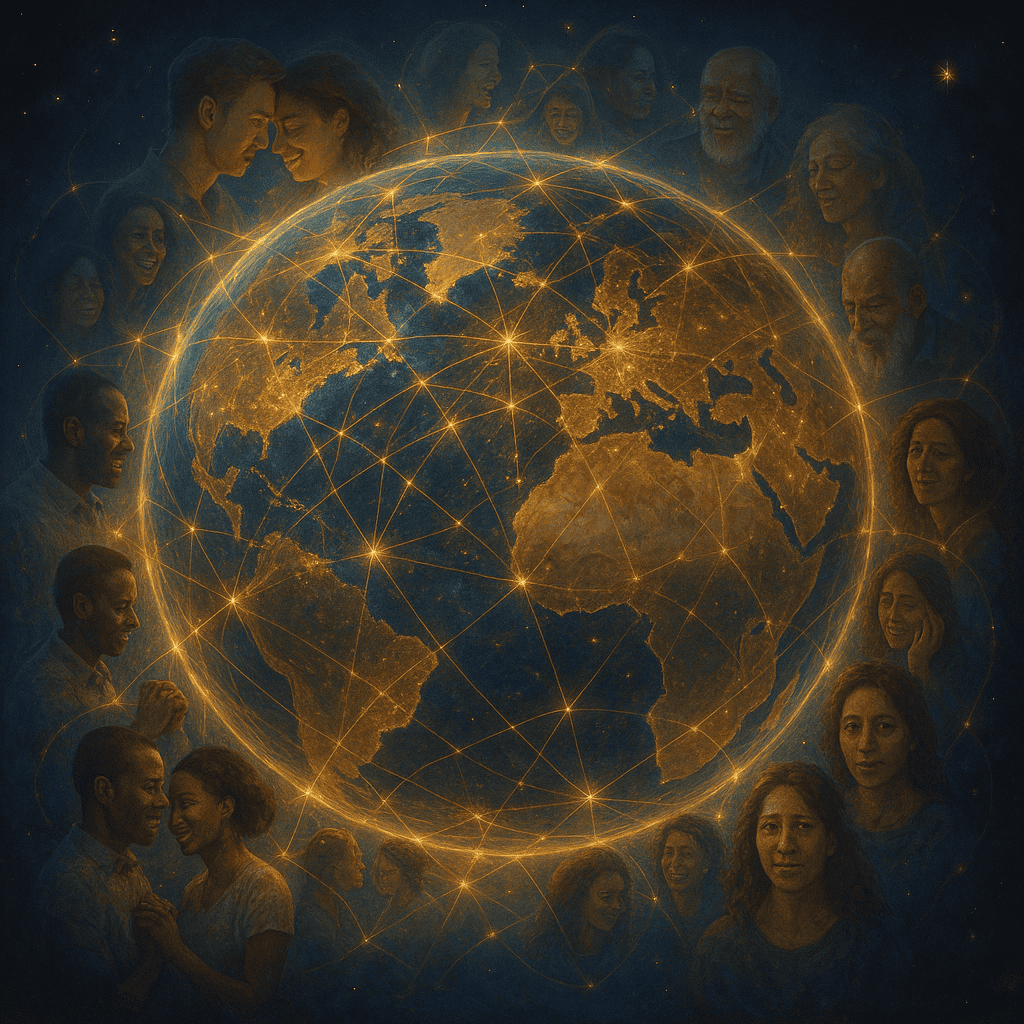

7. The Internet and the Networked World

If personal computers put power in your hands, the internet wired that power into a collective mind.

The idea of networked computing wasn’t new. Military researchers were thinking about it as early as the 1960s. But the execution? Pure Cold War urgency.

It began with ARPANET, a Pentagon project designed to connect a few trusted computers across U.S. research institutions. In 1969, it transmitted its first message: “LOGIN.” The system crashed after the “L” and “O.” Still—history made.

By the 1980s, ARPANET had morphed into a growing inter-network of universities, government bodies, and eventually, public access points. Protocols like TCP/IP (developed in part by Vint Cerf and Bob Kahn) standardized communication. Computers finally spoke the same language, over any distance.

Then came 1990.

Tim Berners-Lee, working at CERN, proposed something deceptively simple: a universal way to access information across the internet. The result? The World Wide Web—a hyperlinked, visual layer on top of the network. Add a browser (hello, Mosaic), sprinkle in some HTML, and suddenly, anyone could create and consume content.

The explosion was immediate. By the mid-’90s, dot-coms were booming, AOL was mailing you a hundred CDs a week, and “You’ve Got Mail” was a lifestyle. Websites, emails, chatrooms—suddenly the web wasn’t just for coders. It was for everyone.

Search engines like AltaVista and Google turned chaos into order. Amazon sold books. eBay sold everything. Napster broke music. Wikipedia rewrote knowledge. Social networks rewired how we socialize—and monetize—ourselves.

Behind the screen, the tech was evolving too: broadband replaced dial-up, Wi-Fi cut the cords, fiber lit up whole cities. Cloud computing virtualized everything. Servers stopped being machines in a room and became services you could summon from anywhere.

The internet didn’t just connect computers. It connected people, data, systems, cultures, economies. It built the modern hive mind—and with it, a new kind of dependency.

In the blink of a few decades, “being online” became indistinguishable from being alive.

8. The Science of Computer Science

Before it was an industry, before it was culture, computer science was a question: What can be computed?

The answers didn’t come from Silicon Valley—they came from mathematics departments. In the mid-20th century, universities like Cambridge, Princeton, and Manchester began formalizing what had once been pure abstraction. The goal? Understand the logic, language, and limits of machines—even before the machines were real.

This wasn’t just tech. It was theory. And it was radical.

At its core, computer science asked how problems could be broken down into steps—algorithms—and how data could be shaped, sorted, stored, and retrieved. It gave birth to data structures (arrays, trees, hash maps), computational complexity theory (P vs NP, anyone?), and whole categories of programming languages built to turn logic into function.

Meanwhile, coders and scientists were asking: How do we write instructions for a machine that’s faster, smarter, more reusable? Enter the rise of programming paradigms—procedural, object-oriented, functional. If hardware was the body, this was the language of the mind.

But it didn’t stop at logic. Computer science expanded into networks, databases, cryptography, human-computer interaction, graphics, and more. It spun out into entire disciplines: software engineering, cybersecurity, AI, and machine learning.

By the late 20th century, computer science wasn’t just an academic curiosity—it was a foundational science, with departments popping up at every major university and graduates shaping the world’s infrastructure.

Then came the meta shift: teaching machines to learn.

Artificial intelligence—once a fringe pursuit—became core curriculum. Neural networks evolved from theoretical models to engine rooms of innovation. Algorithms weren’t just following instructions anymore. They were detecting tumors, writing poems, driving cars.

And yet, the discipline remained grounded in its origins. Every breakthrough still echoed Turing, Lovelace, Gödel: logic meets language meets limits.

Computer science isn’t just about building better software. It’s about understanding how thought itself can be encoded, optimized, and scaled.

We didn’t just invent machines to think faster—we invented a new way to think.

9. Building a Computer: Anatomy of a Thinking Machine

Strip away the screen. Pop the case. What you’re looking at isn’t magic—it’s modular logic.

A modern computer is a symphony of silicon, copper, and code. Each part is doing something very specific, very fast, and very coordinated. It’s not a single brain—it’s a network of organs, optimized to process, store, transmit, and display.

Let’s break it down:

- CPU (Central Processing Unit):

The brain. Everything goes through this. It fetches instructions, executes them, and sends the results flying. Clock speed, cores, cache—it’s all about how fast and how many tasks it can juggle at once. - RAM (Random Access Memory):

Your system’s short-term memory. RAM holds whatever the CPU’s currently working on. More RAM = more multitasking, less lag. - Storage (SSD/HDD):

Long-term memory. SSDs (solid-state drives) are lightning fast, while HDDs (hard disk drives) are cheaper but slower. This is where your files, apps, and OS live when the machine’s off. - Motherboard:

The nervous system. It connects everything—CPU, RAM, storage, GPU, ports—into one synchronized flow of electricity and logic. - Power Supply (PSU):

Converts wall power into voltages your machine can actually use. Unsexy but crucial. - GPU (Graphics Processing Unit):

Originally built for rendering pixels, now moonlighting as a parallel computing beast—especially for gaming, AI, and crypto mining. - Cooling System:

Fans, heatsinks, maybe even liquid. These keep the fire-breathing silicon from melting itself. - Case:

The chassis. It’s where all the components live—form meets function, airflow meets aesthetics.

And then there’s everything that lives on the edges:

- I/O (Input/Output):

Keyboard, mouse, touchscreen, camera, microphone—how you talk to the machine. - Display:

Monitors and screens translate digital states into visible light. 4K, OLED, ultra-wide—it’s all about pixels per inch and refresh rates.

Want to build one yourself? It’s not just doable—it’s a rite of passage. You’ll need a screwdriver, thermal paste, some patience, and a YouTube rabbit hole. Assemble the parts, plug in the cables, fire up the BIOS—and suddenly, you’ve bootstrapped intelligence from scratch.

It’s tactile, empowering, and oddly poetic: a machine made of standardized parts, capable of infinite thoughts.

You didn’t just build a box. You built a system. A mind.

10. Programming Languages: Teaching the Machine to Think

If hardware is what computers are, programming is what they do. And at the center of it all is code—structured language built to bend electrons to our will.

Programming is how humans teach machines. But machines don’t speak English. They speak binary—zeroes and ones, on and off. So we invented languages that could translate our logic into the raw voltage of computation.

It started simple. Assembly language was a human-readable layer on top of machine code. It was fast, brutal, and unforgiving—every instruction mapped directly to a processor action. Efficient, but about as friendly as a tax audit.

Then came high-level languages—the real breakthrough. With FORTRAN (1957), scientists could write equations almost like they thought them. COBOL brought computing to business. LISP gave AI researchers the symbolic power they craved. By the 1970s, languages were proliferating faster than modems in the ’90s.

Enter the big players:

- C: Portable, powerful, and close to the metal. Still running everything from operating systems to microcontrollers.

- Java: “Write once, run anywhere.” Platform-agnostic and object-oriented, it became the lingua franca of the early internet.

- Python: Clean, elegant, forgiving. A favorite for beginners—and now powering everything from data science to deep learning.

- JavaScript: The engine of the web. It made browsers programmable and gave us everything from dynamic UIs to memes.

- Rust, Go, TypeScript, Swift: Newer languages built for speed, safety, and scale—each with its own community, quirks, and cult following.

But writing code isn’t just about syntax. It’s about thinking in logic. You break problems into steps. Use control structures (if, for, while). Define functions. Pass variables. Handle exceptions. It’s closer to writing music than doing math—a balance of creativity, structure, and fluency.

Then there’s the invisible infrastructure:

- Compilers translate high-level code into machine code.

- Interpreters run code line-by-line in real time.

- IDEs (Integrated Development Environments) bundle all your tools—syntax highlighting, debugging, Git integration—into one cockpit.

- APIs let your program talk to someone else’s.

- Version control systems like Git track every change, fork, and panic commit you make.

Programming is now more than a skill—it’s a culture. Open source. Agile. Stack Overflow. Coding bootcamps. Hackathons. GitHub stars. In the Age of Intelligence, code is currency, and fluency is power.

Because once you can write instructions, you don’t just use machines—you command them.

11. Website Building and Web Design: Shaping the Digital World

If code is the DNA of computing, websites are its face. They’re how we see, interact with, and live inside the internet. And behind every sleek homepage, scrolling animation, or product page is a carefully orchestrated blend of design, structure, and code.

The Front End: Where Design Meets Code

Building a website starts with the front end—everything users see and touch. It’s a blend of three core languages:

- HTML gives structure: headers, paragraphs, images, buttons.

- CSS adds style: colors, fonts, layout, spacing, animation.

- JavaScript adds interactivity: dropdown menus, sliders, forms that respond without reloading the page.

Together, they form the holy trinity of web design.

Modern front-end development uses frameworks like React, Vue, or Svelte, which make complex interfaces smoother, faster, and more modular. You’re not just coding pages anymore—you’re building components that act like self-contained apps.

Design matters. A lot. Good design isn’t just aesthetic—it’s behavioral. It guides attention, simplifies choices, builds trust. Web designers now speak fluently in UX (user experience) and UI (user interface) principles: grid systems, color theory, accessibility, loading speed. If your site takes longer than 3 seconds to load, half your users are gone.

The Back End: Logic in the Shadows

But a pretty site is just a shell without a back end—the logic layer that talks to databases, processes forms, serves up content, and handles authentication.

Back-end developers use languages like Python, Node.js, Ruby, PHP, or Java, depending on the stack. Data lives in databases (MySQL, PostgreSQL, MongoDB), and servers run it all, often virtualized in the cloud (AWS, Azure, Google Cloud).

Full-stack developers? They do it all. Front, back, and the logic in between.

From Builders to Platforms

Once, building a website meant raw code. Now, platforms have democratized the process:

- WordPress powers over 40% of the web. Open-source, modular, plugin-friendly.

- Wix, Squarespace, and Webflow let you drag, drop, and publish—no code required.

- GitHub Pages, Netlify, and Vercel deploy code-built sites with push-button ease.

Meanwhile, mobile-first design, responsive layouts, and accessibility standards have become non-negotiables. Your website needs to work on every screen, for every user.

The Culture of the Web

Web design isn’t just a tech skill—it’s a creative discipline. It sits at the intersection of programming, art, marketing, and psychology. It asks: What do people want to see? How do they move? Where do they click? What makes them stay?

A good website doesn’t just inform—it feels alive. Fast. Fluid. Intentional.

And in a world where your online presence is your presence, knowing how to shape the web means knowing how to shape perception.

12. The Future of Computing: Beyond Silicon, Beyond Human

We built machines to solve problems. Now we ask them to predict, create, decide—and in some cases, improve themselves. The question isn’t just what will computers do next? It’s what won’t they do?

The boundaries of computing are being redefined, one breakthrough at a time.

Quantum Computing: Logic in Superposition

Traditional computers think in binary. But quantum computers use qubits—bits that can exist in multiple states simultaneously, thanks to quantum superposition. That means exponential leaps in processing power for specific tasks like factoring large primes, modeling molecular interactions, and optimizing beyond human comprehension.

The race is on: IBM, Google, and startups like Rigetti are pushing qubit counts higher, while researchers tackle the holy grail—quantum error correction. We’re not there yet, but when we are, it’ll be like upgrading from fire to fusion.

AI and Machine Learning: From Code to Cognition

Computers don’t just execute anymore—they learn. Thanks to neural networks, large language models, and reinforcement learning, machines are mastering natural language, vision, decision-making, and even creativity.

AI now writes poems, diagnoses cancer, paints dreamlike images, trades stocks, and runs call centers. In some cases, it writes code better than humans. And it’s just getting started.

The challenge isn’t just capability—it’s ethics, control, and alignment. In an age of AI, intelligence isn’t scarce. Wisdom is.

Neuromorphic Chips and Edge Computing

Brains don’t run on silicon. They run on neurons and spikes. Neuromorphic computing mimics that structure—low power, high parallelism, real-time responsiveness. Combine that with edge computing (processing data on-device, not in the cloud), and you get intelligent systems that are fast, local, and autonomous.

Think: self-driving cars that don’t need to phone home, wearables that adapt on the fly, and robots that improvise.

Sustainable and Ethical Computing

The future isn’t just about more power—it’s about responsible power. Data centers already consume more energy than some countries. Green computing—energy-efficient chips, carbon-neutral clouds, biodegradable hardware—is becoming a design imperative, not an afterthought.

Then there’s digital equity: ensuring access, representation, and safety for everyone online. The next billion users won’t look like the last. Their needs, languages, and infrastructures will redefine how we build.

Biocomputing, Brain Interfaces, and Beyond

Experiments are underway to grow computers from biological matter, integrate chips with neurons, and read thoughts via brain-computer interfaces. It sounds sci-fi—but so did pocket supercomputers twenty years ago.

As computation moves from the desktop to the bloodstream, the line between technology and biology blurs. Will we become part of the machine? Or will the machine become part of us?

The Age of Intelligence

We are leaving the Information Age and entering the Age of Intelligence. Not just artificial intelligence—but distributed, embedded, ubiquitous intelligence. Smart homes, smart grids, smart everything.

But with intelligence comes responsibility. What we build reflects who we are—and who we want to become.

Because in the end, computing isn’t just about machines. It’s about amplifying humanity.