Table of Contents

- Introduction

Anthropology, Sociology, and the Integrated Humanist Perspective - The Birth of Anthropology and Sociology

From Cultural Inquiry to the Sciences of Society - Human Evolution and the Emergence of Social Hierarchies

From Egalitarian Bands to Institutional Inequality - Ancient Civilizations and Class Stratification

Hierarchy and Power from India to Rome - From Monarchy to Republic to Neoliberalism

The Transformation and Persistence of Social Class - Nationalism, Patriotism, and Social Identity

Belonging, Exclusion, and the Power of the Nation-State - Individualism, Tribalism, and the Social Contract

Balancing Freedom, Loyalty, and Moral Responsibility - Global Inequality and Human Rights

Structural Injustice and the Ethics of Dignity - What Anthropology and Sociology Teach Us

Understanding Humanity to Transform Society - The Present and Future—A Sociological Diagnosis

Global Power, Digital Elites, and Class Disruption - Toward an Integrated Humanist Society

Redesigning the World with Ethics, Knowledge, and Compassion

I. Introduction

What does it mean to be human—and how do we live together? These two questions lie at the heart of the intertwined sciences of anthropology and sociology, disciplines devoted to understanding the full range of human life, from our evolutionary roots to the complexity of our modern societies.

Anthropology explores our species across time and cultures, encompassing biology, behavior, and belief. Sociology, meanwhile, examines how human beings live together in structured communities, tracing the patterns of power, inequality, identity, and cooperation that shape our shared existence.

Together, these fields offer powerful tools for grasping both our diversity and our common humanity. They reveal how cultures evolve, how hierarchies are built and contested, and how individuals and institutions interact in shaping the human story. They help us analyze how civilizations organize themselves—through classes, castes, laws, religions, and economic systems—and how these structures affect human dignity, justice, and well-being.

This article is written from the perspective of Integrated Humanism, a framework that blends scientific inquiry, human rights, and ethical reflection to seek a more just and compassionate world. Integrated Humanism holds that science should serve humanity—not merely describe it. It affirms the dignity of all persons, respects the diversity of cultures, and seeks evidence-based pathways toward global justice, equality, and peaceful coexistence.

In the pages that follow, we will journey through the origins and development of anthropology and sociology, trace the history of social hierarchy and class division from ancient civilizations to the present global economy, and explore key social concepts—patriotism, nationalism, tribalism, individualism, and human rights—through a humanist lens.

We will ask not only how humans have evolved and structured society, but also why some systems uplift human dignity while others suppress it. And finally, we will examine how these disciplines can guide us toward a future in which human evolution is not merely biological, but ethical and collective.

II. The Birth of Anthropology and Sociology

A. The Origins of Anthropology

Anthropology, from the Greek anthrōpos (human) and logos (study), is the scientific discipline devoted to understanding humanity in its full biological and cultural range. Its formal emergence occurred during the 19th century, a period marked by colonial expansion, industrialization, and a growing European curiosity about non-Western peoples. Yet its deeper roots lie in ancient inquiries into human nature, custom, and difference—from Herodotus’s ethnographic descriptions to Islamic and Chinese writings on distant cultures.

The modern discipline of anthropology was shaped by pioneering figures such as:

- Edward Burnett Tylor (1832–1917), who defined culture as a “complex whole” including knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, and custom.

- Sir James George Frazer (1854–1941) was a key figure in early anthropology, best known for his groundbreaking work, The Golden Bough, and his contributions to understanding the evolution of human thought and institutions.

- Franz Boas (1858–1942), the father of American anthropology, who championed cultural relativism and opposed scientific racism.

- Bronisław Malinowski (1884–1942), who developed immersive fieldwork methods through long-term participant observation.

Anthropology gradually developed into four major subfields:

- Cultural Anthropology – studies beliefs, rituals, languages, and institutions.

- Biological Anthropology – explores human evolution, genetics, and physiology.

- Archaeology – reconstructs past societies through material remains.

- Linguistic Anthropology – investigates the relationship between language and culture.

Together, these branches provide a holistic view of human life, combining the empirical rigor of science with the interpretive insight of the humanities.

B. The Origins of Sociology

Sociology, from the Latin socius (companion) and logos (study), arose in the wake of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution. As Europe experienced seismic transformations—urbanization, class upheaval, secularization—early thinkers sought to understand the rules governing society, not by divine authority but by observation, theory, and critique.

Foundational figures in sociology include:

- Auguste Comte (1798–1857), who coined the term sociology and proposed a “science of society” governed by positivist laws.

- Émile Durkheim (1858–1917), who studied social cohesion and the role of institutions in maintaining order.

- Karl Marx (1818–1883), who critiqued capitalism and theorized class struggle as the engine of historical change.

- Max Weber (1864–1920), who analyzed the intersection of culture, bureaucracy, and rationality in modern society.

Sociology centers on the study of:

- Social structures (e.g., class, race, gender)

- Social institutions (e.g., family, religion, economy, government)

- Social processes (e.g., socialization, deviance, mobility)

- Social change (e.g., revolution, reform, globalization)

Where anthropology often begins with cultural diversity across space, sociology typically analyzes structural patterns and social forces across time and within societies. Both disciplines are complementary and overlapping, united in their aim to understand how humans live together.

C. The Integrated Humanist View

From the standpoint of Integrated Humanism, anthropology and sociology are not only scientific fields—they are ethical instruments. They reveal how belief systems, political ideologies, economic practices, and historical narratives shape the lived experience of individuals and groups. They expose the foundations of inequality and offer tools for creating a more equitable world.

An Integrated Humanist approach to these disciplines involves:

- Empathy and respect for cultural diversity, without romanticizing or relativizing injustice.

- Evidence-based analysis of social systems, using both qualitative and quantitative methods.

- Commitment to universal human dignity, challenging hierarchy and oppression.

- Global consciousness, recognizing that human welfare transcends national borders.

In a world facing crises of identity, inequality, and climate, anthropology and sociology offer essential lenses through which to see ourselves—clearly, compassionately, and constructively.

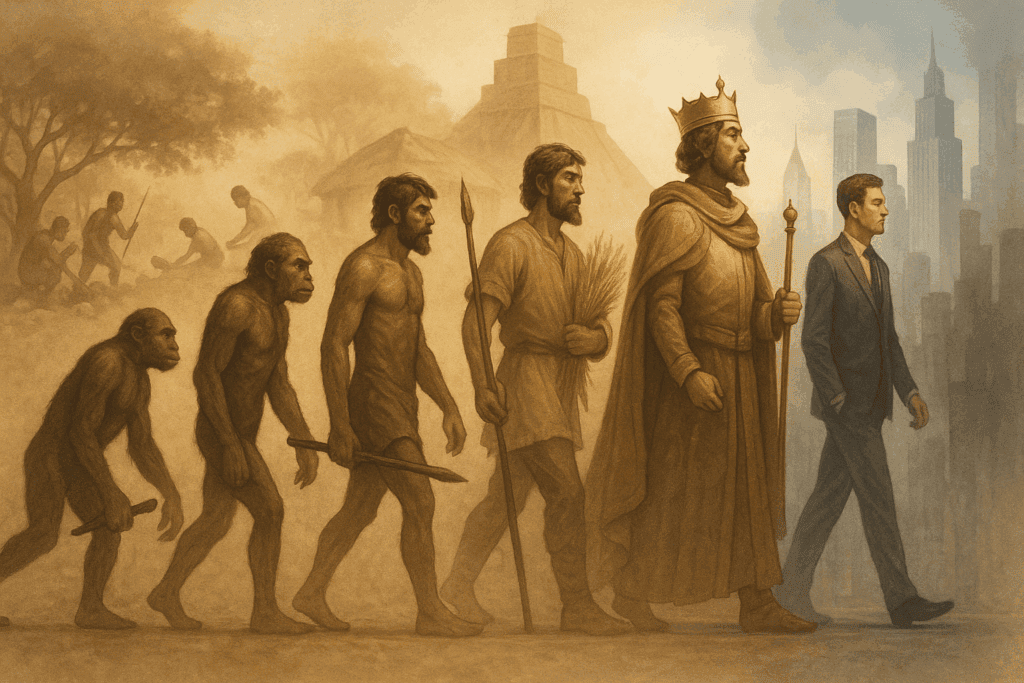

III. Human Evolution and the Emergence of Social Hierarchies

A. The Anthropological Perspective on Human Evolution

Human beings are the product of millions of years of evolutionary development—a story not merely of biology, but of social and cooperative behavior. From the earliest hominin species such as Australopithecus to the rise of Homo sapiens approximately 300,000 years ago, humans evolved not as solitary creatures, but as deeply social animals. Survival depended on communication, cooperation, and the ability to form complex emotional bonds.

Key evolutionary traits—upright walking, large brains, tool use, fire control, and eventually, language—enabled early humans to adapt to a wide range of environments. But it was culture—the transmission of learned knowledge across generations—that allowed Homo sapiens to create stable societies and rapidly expand across the globe.

B. Egalitarian Beginnings: Hunter-Gatherer Societies

For most of human history, people lived in hunter-gatherer bands of 20 to 100 individuals. These societies were generally egalitarian, with relatively little material accumulation and decision-making shared among elders or councils. Gender roles existed but were not typically rigid or hierarchical; mobility and mutual reliance discouraged strong social stratification.

Status differences existed—based on age, wisdom, or ability—but they were fluid and rarely institutionalized. Leadership was situational and based on competence rather than inheritance or domination. Archaeological and ethnographic evidence suggests that early humans were more cooperative than competitive, bound together by kinship, storytelling, and ritual.

C. The Agricultural Revolution and the Roots of Inequality

Around 10,000 years ago, the Neolithic Revolution began to transform human societies. The domestication of plants and animals enabled permanent settlements and the accumulation of surplus food. With it came new forms of ownership, specialization of labor, and control over land and water—paving the way for social stratification.

Some individuals or groups began to control the distribution of resources. Hierarchies emerged based on wealth, lineage, priesthood, or warrior status. The first signs of institutional inequality appear in burial sites with rich grave goods for some and modest or none for others, and in early cities with walls, temples, palaces, and slums.

These changes laid the groundwork for class societies, with codified roles, inherited privilege, and ruling elites justified by religion or divine right.

D. Early Forms of Political Hierarchy

As communities expanded, social organization became more formalized. Chieftainships arose—centralized authorities where charismatic or hereditary leaders governed small tribal confederations. Later, kingship systems developed, often reinforced by religious narratives that sacralized the leader’s authority.

Three key sources of early hierarchical power were:

- Spiritual authority – shamans, priests, oracles

- Martial authority – warriors, protectors, conquerors

- Economic control – those who distributed food, tools, land

These systems increasingly led to permanent inequality, as children inherited rank and resource access. Hierarchy became self-reinforcing, often enforced through coercion, ideology, or both.

E. Integrated Humanist Reflections

From an Integrated Humanist perspective, this evolutionary history presents both a warning and a possibility. Hierarchy is not inevitable—but neither is equality. Human societies are shaped by circumstance, choice, and cultural evolution. Our capacity for cooperation is as ancient as our capacity for domination.

Understanding the anthropological roots of hierarchy helps us distinguish between natural human differences (skills, preferences, personalities) and socially constructed inequalities (class, caste, race, gender oppression). It also opens the door to conscious redesign—building systems that preserve diversity and recognize ability while safeguarding universal human dignity.

In studying how hierarchy began, We the People prepare to ask: how can it be transformed for the benefit of the greater whole?

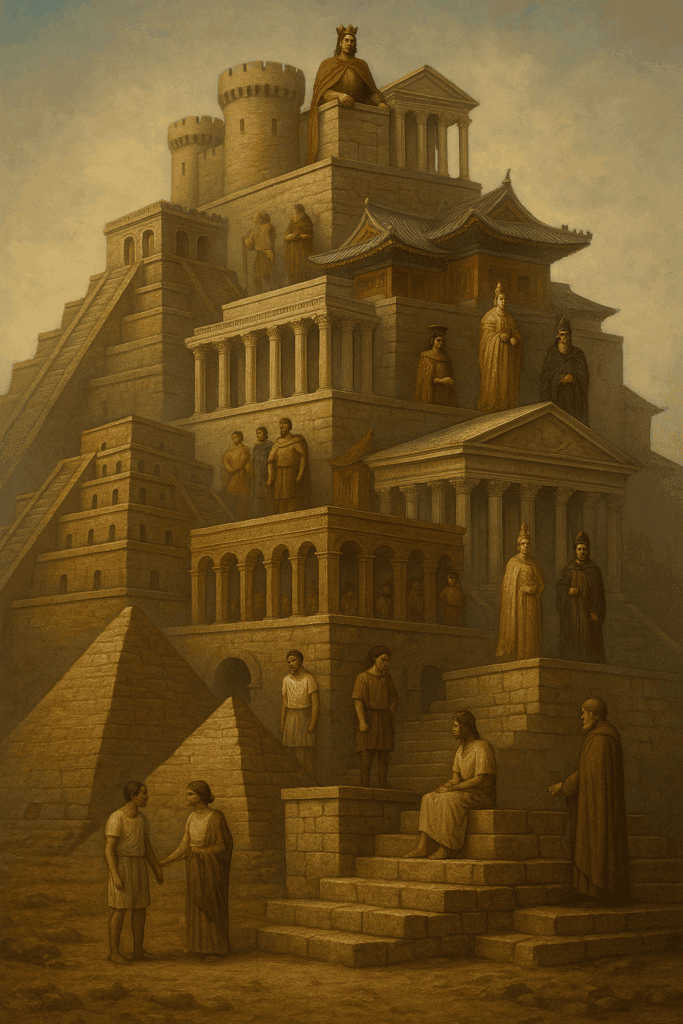

IV. Ancient Civilizations and Class Stratification

As human societies transitioned from small, kin-based groups to large urban civilizations, systems of hierarchy became more elaborate, codified, and enduring. The emergence of agriculture, trade, writing, and statecraft brought about the institutionalization of class, where birth, occupation, and power were increasingly fixed within a rigid social structure.

Across the ancient world—from South Asia and East Asia to the Near East, North Africa, and Europe—distinct forms of social stratification evolved, often underpinned by religion, law, and ideology.

A. India: The Caste System and Religious Hierarchy

India’s ancient social organization is famously expressed in the Varna system, later expanded into the complex and enduring caste system (jati). The Varna system, articulated in the Vedic texts, divided society into four idealized classes:

- Brahmins – priests and scholars

- Kshatriyas – warriors and rulers

- Vaishyas – merchants and landowners

- Shudras – laborers and service providers

Outside this system were the Dalits (formerly “Untouchables”), who were subjected to severe discrimination and exclusion. Though religious in origin, caste became a mechanism for maintaining rigid social control, discouraging upward mobility and regulating marriage, work, and social interaction.

Despite efforts at reform, the caste hierarchy continues to shape Indian society. From a humanist standpoint, it exemplifies a spiritually sanctioned form of inequality, where metaphysical belief perpetuated material subjugation.

B. China: Meritocracy and the Mandate of Heaven

Ancient China developed a hierarchical yet complex system of governance based on Confucian philosophy and the Mandate of Heaven—a divine principle that legitimized just rule and allowed for the overthrow of corrupt dynasties.

Socially, the traditional Chinese order was structured as:

- Emperor – Son of Heaven

- Scholar-officials (shi) – selected through civil service exams

- Peasants – valued for producing food

- Artisans and merchants – seen as profit-seeking, morally inferior

- Soldiers and slaves – marginal or subordinated groups

While this system honored education and service, it was still deeply hierarchical. The civil service exam offered limited mobility but was only accessible to those with resources for schooling. Confucian values emphasized order, duty, and respect for superiors, reinforcing patriarchal and age-based hierarchies.

Integrated Humanism respects Confucian ethics of responsibility but critiques the gatekeeping of merit and the exclusion of women, minorities, and the poor from meaningful participation.

C. Mesopotamia and Egypt: Divine Kingship and Slavery

In Mesopotamia (Sumer, Akkad, Babylon) and Egypt, social hierarchy was anchored in divine kingship. Rulers claimed descent from or favor of the gods, combining religious, military, and administrative authority.

Society was typically divided into:

- King and royal family

- Priests and scribes

- Nobles and military officers

- Merchants and artisans

- Peasants and laborers

- Slaves (captives, debtors)

Law codes such as Hammurabi’s codified unequal rights, assigning different punishments based on class and gender. In Egypt, the Pharaoh was worshipped as a living god, and massive labor forces (often coerced) built temples and pyramids to reinforce divine authority.

These early states illustrate theocratic justification for hierarchy, where religious belief became state ideology.

D. Persia: Centralized Bureaucracy and Multicultural Empire

The Persian Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BCE) developed one of the world’s first multiethnic bureaucratic empires, governed through satraps—regional governors who reported to the king.

Although the Persian system allowed religious and cultural tolerance, class distinction was still clear:

- King of Kings (Shahanshah)

- Nobility and military elite

- Satraps and administrators

- Craftspeople and farmers

- Servants and slaves

Zoroastrianism, the state religion, emphasized moral dualism and kingship as divinely sanctioned. Though not as rigid as caste or Confucian orders, Persian hierarchy reflected centralized control, with the monarchy at the apex of a tightly managed imperial machine.

E. Greece: Citizens, Slaves, and “Natural” Hierarchy

Classical Greece—especially Athens—is often celebrated as the birthplace of democracy, yet its social structure was deeply exclusionary.

- Citizens (free adult Athenian males): held voting and property rights

- Metics (resident foreigners): no political rights

- Women: legal minors, confined to domestic roles

- Slaves: considered property, essential to the economy

Philosopher Aristotle famously argued that some people were “natural slaves” and that hierarchy was inherent to human society. His political theories reinforced male, citizen, and elite privilege—ideas that profoundly shaped Western social thought.

From a humanist view, Greek intellectual achievements are overshadowed by systemic injustice masked as rational order.

F. Rome: Republican Ideals and Imperial Stratification

The Roman Republic introduced ideas of law, citizenship, and shared governance—but these ideals coexisted with stark inequality:

- Patricians – aristocratic families with senatorial power

- Plebeians – commoners with limited rights

- Freedmen – former slaves, often stigmatized

- Slaves – a vast class with no rights

The transition to Empire concentrated power in the hands of emperors and military elites. Roman society was militaristic, patriarchal, and built on conquest and forced labor. Yet, Roman law and citizenship ideas also laid foundations for later Western liberalism.

Rome shows how republican values can coexist with brutal inequality, a tension still present in modern democracies.

G. Europe’s Feudal Order: Nobility, Clergy, and Serfs

In medieval Europe, hierarchy was structured as a feudal pyramid:

- King – divine right ruler

- Nobility – land-owning aristocrats with hereditary titles

- Clergy – spiritual leaders with social and political influence

- Knights – warrior class pledged to nobles

- Peasants/Serfs – tied to the land, little freedom

In France, aristocracy held extravagant privilege until the Revolution. In England, the peerage was formalized through titles and property, influencing Parliament and monarchy alike.

The Enlightenment and revolutions of the 18th century challenged this system, but vestiges of noble privilege remain—in inherited wealth, elite education, and lingering class identities.

Integrated Humanist Reflection

The civilizations of antiquity offer lessons in both innovation and injustice. Hierarchy, while often framed as necessary for order, frequently served to entrench privilege and suppress others—especially women, the poor, foreigners, and the enslaved.

From the Integrated Humanist perspective, history must be neither romanticized nor rejected, but studied to extract ethical insight. We honor the architectural, artistic, legal, and philosophical achievements of ancient societies while critiquing their systems of dehumanization.

If class stratification is a human invention, it can also be re-invented—or transcended—in pursuit of societies that are just, inclusive, and based on merit, need, and dignity rather than birth and power.

V. From Monarchy to Republic to Neoliberalism

Across centuries, the arc of human governance has moved—though not linearly—from divine kingship and hereditary nobility toward ideals of citizenship, rights, and representation. The journey from monarchy to republic has been complex and incomplete, as new systems of freedom have often reproduced old patterns of power in subtler forms. In modern times, neoliberalism has become the dominant global ideology—championing market freedom while often undermining social equity.

Understanding these transitions is key to grasping the evolution of class structures and political identity in the modern world.

A. The Decline of Monarchy and Rise of the Republic

The Enlightenment of the 17th and 18th centuries brought a revolution in thought. Thinkers like Locke, Rousseau, and Montesquieu challenged the divine right of kings and proposed social contracts, separation of powers, and government by consent.

These ideas inspired real-world revolutions:

- The American Revolution (1776) – rejected British monarchy in favor of representative democracy, rooted in liberty and natural rights.

- The French Revolution (1789) – overthrew aristocracy and proclaimed universal human rights, though it was quickly followed by instability and empire.

These events marked a profound reimagining of political legitimacy—no longer based on bloodlines or sacred authority, but on reason, justice, and the will of the people.

Yet even in new republics, inequality persisted. Voting was restricted by property and gender; slavery and colonialism endured. The promise of equality was aspirational, not actualized.

B. Industrialization and Capitalist Class Divisions

The 19th century saw the rise of industrial capitalism, transforming economies and societies. Monarchs gave way to parliaments and corporations; landed aristocracy was challenged by a new bourgeoisie—urban industrialists, bankers, and entrepreneurs.

Class divisions became more economically defined:

- Capitalist class (owners of production and finance)

- Petite bourgeoisie (small business owners, clerks, professionals)

- Working class (industrial laborers, often underpaid and overworked)

- Poverty-Stricken (experiencing extreme hardship and lacking basic necessities; often houseless)

Karl Marx famously analyzed this system as a new form of exploitation: the capitalist profiting from surplus labor while the worker remained alienated from both product and purpose.

The nation-state became the central structure for managing capitalism, often protecting elite interests through law, force, and nationalism. While democracy expanded in some areas, economic power was increasingly concentrated and globalized.

C. The Welfare State and Mid-20th Century Reform

Following the Great Depression and two world wars, many Western nations adopted welfare state policies to temper the excesses of capitalism:

- Public education, healthcare, and housing

- Social security and labor protections

- Progressive taxation and national infrastructure

This period—from the 1940s to the 1970s—is sometimes called the “golden age” of Western capitalism, when middle classes expanded and inequality narrowed.

These reforms were often driven by sociological insight and political activism, recognizing that mass poverty and inequality destabilize society and violate human dignity. They represented an attempt to balance markets with morality.

D. The Rise of Neoliberalism

In the late 20th century, neoliberalism emerged as a dominant economic philosophy, championed by leaders like Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. Its core principles include:

- Deregulation – removing constraints on business

- Privatization – shifting public services to private control

- Global free trade – minimizing borders for capital, not labor

- Individual responsibility – replacing collective welfare with personal success narratives

Neoliberalism reframed society as a marketplace. Citizens became consumers; workers became entrepreneurs of themselves. Economic value became synonymous with moral worth.

While this approach generated global growth and innovation, it also intensified inequality, weakened labor protections, hollowed out public goods, and eroded democratic accountability.

Sociologists note the emergence of a new ruling elite—a global class of tech CEOs, financial oligarchs, and political influencers—often disconnected from the needs of ordinary people.

E. Integrated Humanist Critique

From an Integrated Humanist standpoint, neoliberalism represents a technocratic resurrection of aristocracy—power concentrated not in bloodlines, but in capital, algorithms, and legal fictions. Markets are treated as natural forces, immune to moral critique, even as they generate vast disparities in wealth, opportunity, and voice.

Integrated Humanism affirms:

- That economic freedom without social justice leads to exclusion and despair

- That democracy requires equality of condition, not just procedure

- That human dignity cannot be reduced to purchasing power

The path forward involves rebalancing economics with ethics—reimagining the social contract to reflect our shared humanity, not merely our market utility.

VI. Nationalism, Patriotism, and Social Identity

Modern identities are shaped not only by class, ethnicity, or religion—but also by nationhood. Since the 18th century, nationalism and patriotism have become powerful forces in shaping how people see themselves, their obligations, and their “others.” These concepts have inspired liberation and solidarity—but also exclusion, war, and tyranny. To understand the modern human condition, we must explore the sociology of belonging—how individuals affiliate with groups, especially nations, and how those affiliations can support or undermine human dignity.

A. Defining Patriotism and Nationalism

Though often used interchangeably, patriotism and nationalism carry distinct meanings and moral connotations:

- Patriotism is the love of one’s country—a sense of civic loyalty, pride in shared values, and willingness to contribute to the common good. It is often inclusive, focusing on service, mutual care, and stewardship.

- Nationalism, by contrast, is the belief in the superiority or primacy of one’s nation. It defines identity in exclusive terms and often seeks to assert dominance over others—militarily, economically, or culturally.

According to sociological analysis, patriotism can foster community cohesion, while nationalism frequently becomes a vehicle for xenophobia, authoritarianism, and violence.

B. The Rise of the Nation-State

Before the modern period, most people identified with villages, tribes, religions, or empires. The idea of a bounded nation-state—a sovereign people with shared language, culture, and government—emerged in early modern Europe and became dominant in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Nationalism played key roles in:

- Anti-colonial movements (e.g., India, Algeria, Vietnam)

- Unification movements (e.g., Italy, Germany)

- Fascist regimes (e.g., Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan)

- Cold War alignments and global conflicts

It gave rise to myths of origin, sacred borders, flags, anthems, and heroes—rituals that substituted for older religious loyalties.

C. The Double Edge of National Identity

Sociologically, national identity offers psychological and social benefits:

- A sense of purpose and community

- Mobilization for democratic participation

- Shared history and civic responsibility

But it also introduces boundaries and binaries:

- Who belongs—and who doesn’t?

- Whose history is told?

- Who is protected—and who is excluded?

When national identity becomes ethnic or racialized, it excludes minorities, immigrants, and dissenters. It can justify violence, surveillance, and repression in the name of unity.

D. Tribalism and Group Identity

Beneath both patriotism and nationalism lies a deeper tribal psychology—the human tendency to favor in-groups and distrust out-groups. Evolutionarily useful for survival, tribalism in modern society manifests as:

- Political polarization

- Sectarian conflict

- Ethnic cleansing and genocide

When stoked by propaganda or crisis, tribal loyalty overrides empathy, reason, and shared humanity. In-group myths become sacred; outsiders become threats.

E. Integrated Humanist Perspective on Identity

From an Integrated Humanist view, identity must be rooted in dignity, not dominance. Cultural pride and community bonds are valuable—but they must be inclusive, dialogical, and open to critique.

Integrated Humanism affirms:

- A civic patriotism based on values, not bloodlines

- Global citizenship that complements national belonging

- The importance of honoring one’s roots without vilifying others

- The rejection of nationalism when it denies human rights or fuels supremacist ideologies

We must cultivate identities that are confident but humble, local but connected, and always guided by universal principles of justice and compassion.

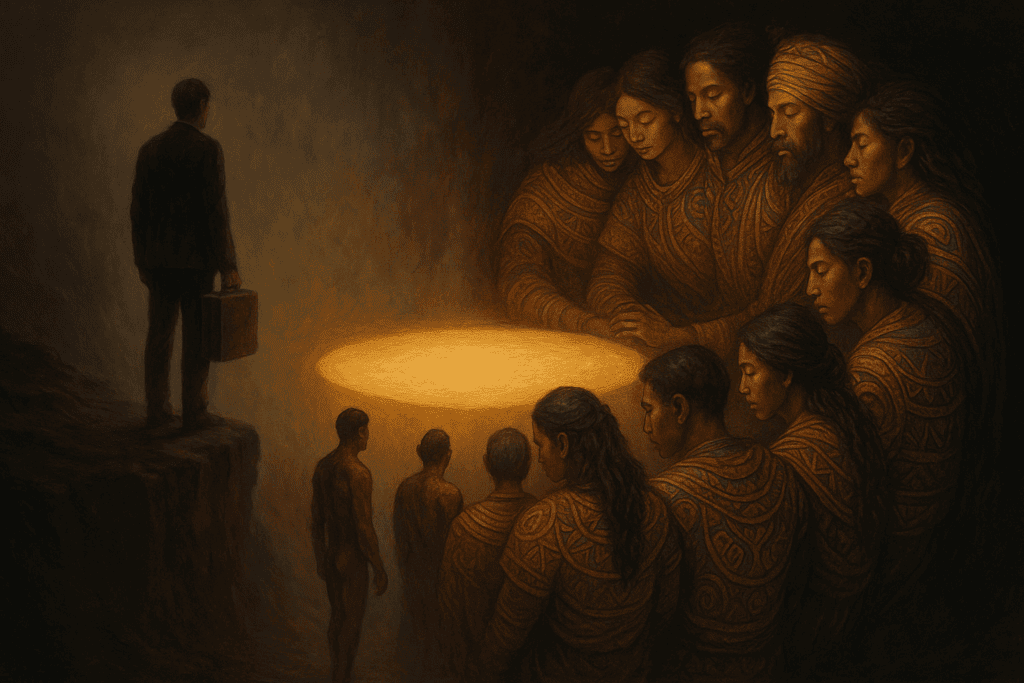

VII. Individualism, Tribalism, and the Social Contract

The human condition is shaped by a tension between individual freedom and collective belonging. We are both singular beings with our own needs, desires, and rights—and social animals, dependent on groups for identity, survival, and meaning. The balance between these forces is negotiated through culture, law, and ideology. In modern societies, this negotiation takes the form of the social contract: an implicit or explicit agreement that defines the relationship between the individual and the community.

A. Individualism: Autonomy and Its Discontents

Individualism—the value placed on personal independence and self-determination—is a hallmark of Western political thought, tracing back to Enlightenment philosophers like John Locke and Immanuel Kant. It asserts that:

- Individuals are the basic units of moral worth

- Each person has natural rights (life, liberty, property, conscience)

- Society exists to protect and empower these rights

This perspective fuels democracy, creativity, and innovation, and underpins movements for civil rights, feminism, and freedom of expression.

Yet individualism also has darker aspects when unchecked:

- Self-interest can override social responsibility

- Hyper-individualism leads to isolation and alienation

- The myth of the “self-made person” obscures systemic inequality

A society too focused on individual gain risks eroding trust, weakening institutions, and reducing people to consumers rather than citizens.

B. Opportunism and Materialism

In capitalist societies, individualism often merges with materialism and opportunism—the pursuit of wealth and status without regard for ethical or communal implications. When success is measured solely by profit or prestige, values such as cooperation, integrity, and solidarity are diminished.

Opportunistic behaviors flourish in:

- Corrupt political systems

- Corporate exploitation

- Online disinformation campaigns

- Profiteering during crises

These tendencies are not inevitable—they are cultural and structural, shaped by incentives, narratives, and power dynamics.

C. Tribalism: The Need to Belong

Humans are evolutionarily wired for tribal loyalty. We find meaning in shared language, symbols, customs, and enemies. Group identity offers emotional safety—but it can also breed exclusion, prejudice, and violence.

Tribalism becomes dangerous when:

- Difference is perceived as threat

- Leaders exploit fear for control

- Myths of purity and destiny override facts and ethics

Whether in sectarian conflicts, partisan politics, or digital echo chambers, tribalism reduces people to categories and shuts down empathy.

D. Prejudice, Extremism, and Genocide

At its worst, tribalism fuels prejudice (prejudgment based on group identity), extremism (ideological purity over pluralism), and even genocide—the deliberate destruction of a people based on race, religion, or ethnicity.

Sociological and anthropological studies have shown that genocide often arises not from ancient hatred, but from:

- Political manipulation

- Scapegoating during crises

- Dehumanizing language and propaganda

Examples include:

- The Holocaust (Nazi Germany)

- The Rwandan genocide (1994)

- The Rohingya crisis (Myanmar)

Genocide represents the ultimate violation of human dignity—a catastrophic failure of social conscience.

E. The Social Contract: A Humanist Ideal

The social contract is the framework through which society balances freedom and order. Classically theorized by Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau, it suggests that people willingly submit to collective rules in exchange for protection and mutual benefit.

An Integrated Humanist social contract emphasizes:

- The inherent dignity of every person

- The rights of individuals to freedom, education, and well-being

- The responsibilities of citizens to others and to future generations

- The role of the state as a democratic, ethical steward—not a machine of coercion

This vision demands that individual liberty be interwoven with collective justice, and that belonging never be bought at the price of truth, conscience, or inclusion.

From selfishness to solidarity, from tribal rage to civic harmony, the challenge of the modern era is to redefine identity, responsibility, and power in ways that honor both the individual and the collective.

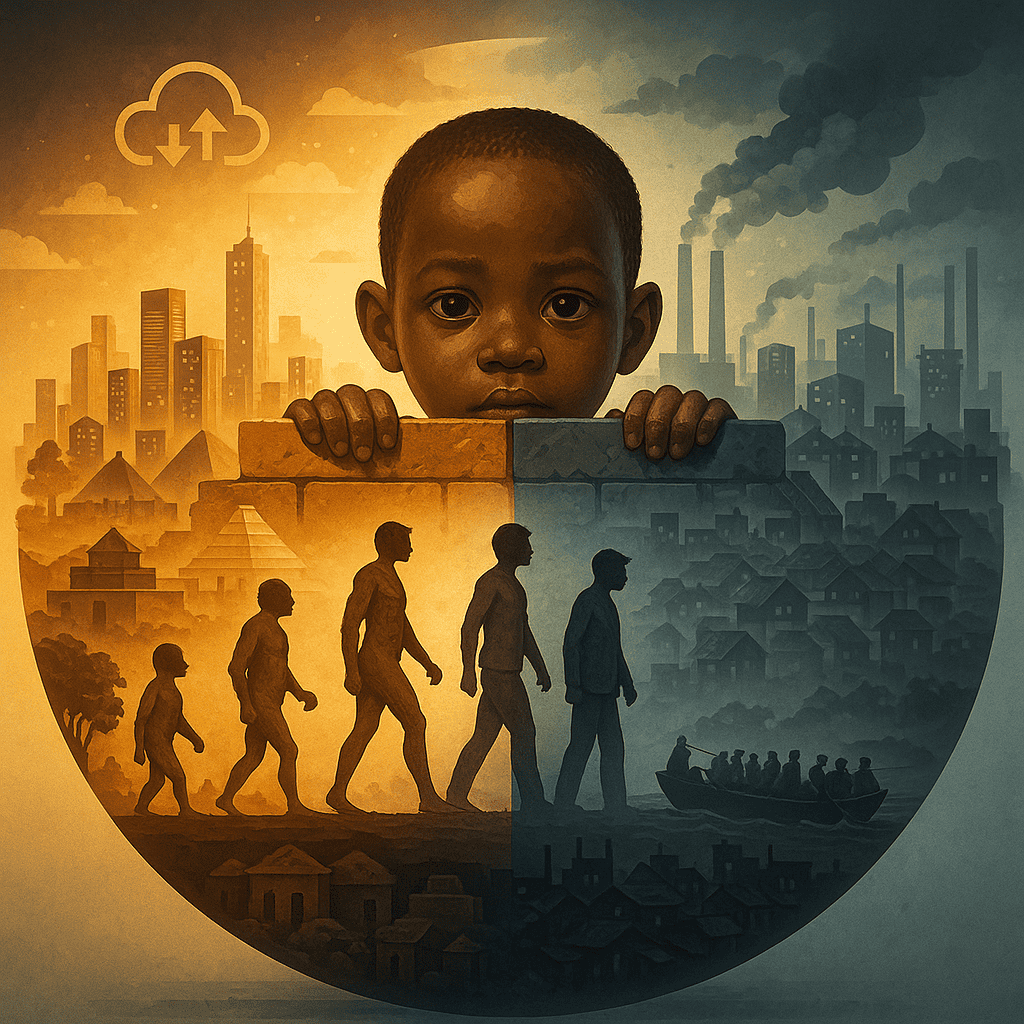

VIII. Global Inequality and Human Rights

Despite technological progress and growing global interconnection, the modern world remains marked by deep inequality—between nations, within societies, and across communities. These inequalities are not merely economic but also social, cultural, legal, and environmental. They manifest in disparities of wealth, health, opportunity, voice, and dignity. The anthropological and sociological sciences reveal these patterns and help expose the mechanisms that produce and sustain them.

A. Economic Inequality and the Global Divide

The global economy is increasingly concentrated in the hands of a small elite. According to recent studies:

- The richest 1% owns more wealth than the bottom half of humanity.

- The global South (Africa, Latin America, South and Southeast Asia) continues to face the legacies of colonialism, debt, and resource extraction.

- Access to clean water, quality education, digital infrastructure, and healthcare remains vastly unequal.

In wealthier nations, income inequality has grown as wages stagnate and capital accumulates among corporate and financial elites. Upward mobility is limited by structural barriers, such as unequal education systems and systemic discrimination.

B. Social Determinants of Health and Opportunity

Sociologists study how social determinants—conditions shaped by where people live, work, and learn—affect health and life chances. These include:

- Income and job security

- Access to education

- Environmental conditions

- Housing and neighborhood safety

- Discrimination and systemic bias

Marginalized groups—especially racial, ethnic, caste, and indigenous minorities—suffer disproportionately from preventable disease, malnutrition, maternal mortality, and inadequate care. Inequality is not abstract; it is lived in the body.

C. Violations of Human Rights and Dignity

Global inequalities are sustained through violations of basic human rights, including:

- Child labor and exploitation

- Political repression and censorship

- Gender-based violence and wage gaps

- Ethnic cleansing and cultural erasure

- Denial of asylum and forced displacement

Human rights are supposed to be universal and indivisible, as codified in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). Yet they are often subordinated to political interest, economic expediency, or ideological control.

Anthropologists have documented both human rights abuses and the resilience of communities struggling to preserve dignity, identity, and freedom in the face of systemic oppression.

D. Integrated Humanism and the Ethics of Equality

From the Integrated Humanist perspective, inequality is not simply a policy failure—it is an ethical crisis. It reflects a disregard for the foundational truth that every human being possesses equal intrinsic worth.

Integrated Humanism asserts that:

- Dignity is non-negotiable—it is not earned by wealth, nationality, race, or status

- Social and economic systems must be designed to promote well-being for all, not privilege for a few

- Justice requires structural transformation, not charity or cosmetic reform

- Global solidarity is a moral imperative, not a utopian dream

Human rights must be more than declarations—they must be enforced by law, education, and public conscience, and informed by cross-cultural understanding.

E. The Role of Anthropology and Sociology

These disciplines contribute uniquely to the cause of equality:

- Anthropology challenges ethnocentrism and affirms cultural plurality. It documents alternative ways of living that resist capitalist and colonial models.

- Sociology exposes the structural mechanisms of inequality—from redlining and caste laws to media bias and bureaucratic exclusion.

Together, they empower us to ask not only what is, but what could be—and to build bridges between the marginalized and the mainstream, the local and the global.

In a world of abundance, persistent inequality is not inevitable—it is constructed. The sciences of humanity must help deconstruct it and lay the foundations for justice, inclusion, and shared human flourishing.

IX. What Anthropology and Sociology Teach Us

At their core, anthropology and sociology are disciplines of understanding—disciplines that take seriously the full range of human experience, across time, cultures, and systems. While their methods differ, their shared goal is to reveal the patterns and possibilities of human life, to uncover how we have come to live the way we do, and how we might live differently—more ethically, justly, and sustainably.

A. Anthropology: The Study of Human Possibility

Anthropology teaches us that humanity is not singular, but plural. The ways people live, think, relate, govern, and find meaning are astonishingly diverse—and often radically different from modern Western norms. By immersing in other cultures, anthropologists challenge ethnocentrism, the belief that one’s own way is natural or superior.

Key lessons include:

- Culture is learned, not biologically inherited.

- Norms and values are variable, even among neighboring groups.

- No society is a model of perfection—but all contain lessons.

- Adaptation is a hallmark of human success—and the key to future survival.

Anthropology also exposes unconscious biases, deconstructs myths of “civilized” vs. “primitive,” and affirms that other ways of being are not only possible, but valid. It cultivates cultural humility and intellectual openness.

B. Sociology: The Science of Social Structure

Sociology focuses on how institutions, ideologies, and power shape people’s lives. Where anthropology highlights cultural difference, sociology uncovers systemic patterns: who has access, who is excluded, and why.

Sociology teaches us:

- Societies are structured, not random.

- Inequality is institutional, not just individual.

- Power operates through norms, language, and institutions.

- Social change is possible, but requires both awareness and action.

Through empirical research—surveys, case studies, statistical models—sociologists uncover how education, religion, media, politics, and economy influence behavior and belief. They explain how identities are constructed, how norms are enforced, and how movements challenge the status quo.

Sociology is not only descriptive—it is diagnostic and transformative.

C. Humanization through the Human Sciences

Anthropology and sociology remind us that no human is a statistic, and no system is above critique. They teach us how to listen, how to question, and how to reimagine.

From an Integrated Humanist perspective, these disciplines are moral tools:

- They promote empathy, by illuminating other lives and perspectives.

- They dismantle injustice, by exposing hidden hierarchies and exclusions.

- They support policy, by grounding decisions in real-world evidence.

- They encourage humility, by reminding us that our way is not the only way.

Together, they provide the intellectual and ethical foundation for scientific humanism—a worldview that seeks truth not only to know the world, but to improve it, with dignity at the center.

Anthropology and sociology do not simply describe the world—they invite us to co-create a better one, through knowledge, compassion, and shared responsibility.

X. The Present and Future—A Sociological Diagnosis

As we navigate the 21st century, humanity stands at a crossroads defined by rapid transformation, deep uncertainty, and persistent inequality. Technological progress has revolutionized communication, labor, and identity, yet many of the ancient patterns of domination, exclusion, and hierarchy persist—sometimes in new forms. Sociology offers tools to analyze the current structures and trends shaping our collective future and provides insight into how we might steer that future toward greater justice and sustainability.

A. Polarization, Displacement, and the Fracturing of Trust

Many societies today are experiencing profound social fragmentation:

- Political polarization divides populations into hostile camps, often amplified by social media algorithms and ideological echo chambers.

- Mass displacement—driven by climate change, war, and economic precarity—has produced over 100 million refugees and internally displaced persons.

- Erosion of institutional trust—in governments, science, media, and democracy—has led to cynicism, apathy, and a surge in conspiracy thinking.

These conditions create fertile ground for authoritarianism, populist nationalism, and social unrest.

B. The Rise of Digital Capitalism and New Elites

A new global elite is emerging, concentrated in the tech, finance, and media sectors. These individuals and corporations:

- Control vast amounts of data, infrastructure, and influence

- Operate beyond the regulatory reach of most nation-states

- Shape public discourse through algorithmic curation and platform dominance

The power of these “info-oligarchs” is structural, not merely economic: they mediate reality, controlling not just what people consume, but how they think and connect. This represents a new form of stratified knowledge economy, where access to digital tools and literacy defines opportunity.

C. The Precarious Class and Eroding Middle

Beneath the elites and traditional upper classes lies a rapidly growing precarious class—people with unstable employment, rising costs of living, and limited social protections. The “gig economy” and freelance digital labor promise flexibility but often deliver insecurity and exhaustion.

Meanwhile, the middle class, once the stabilizing force of liberal democracies, is shrinking. Stagnant wages, student debt, and the decline of unions have weakened its influence, while populist movements harness its grievances.

D. Global Class Trends and the North-South Divide

On a global scale, the legacy of colonialism and economic imperialism has left enduring imbalances:

- Wealthier countries in the Global North consume a disproportionate share of resources and dominate global finance and governance.

- Many countries in the Global South remain locked in cycles of debt, extraction, and climate vulnerability.

- Migration from poor to rich nations is often criminalized, even as labor from the Global South sustains Northern economies.

Sociologically, we are witnessing the emergence of a planetary class system, where nationality, ethnicity, and geography intersect with wealth to determine human worth and mobility.

E. Sociological Responses and Future Pathways

Despite these crises, sociology is not fatalistic—it is a discipline of diagnosis and possibility. It equips us to ask:

- What institutional reforms are needed to redistribute power and resources?

- How can we create participatory democracies that reflect social complexity?

- What models of education, labor, and governance can promote dignity and inclusion?

- How do we design global systems of cooperation that protect both human rights and planetary limits?

From climate justice movements to universal basic income pilots, from grassroots education initiatives to digital cooperatives, new models are emerging. Sociology helps evaluate these efforts—not just for efficiency, but for equity and ethics.

F. Integrated Humanist Outlook

From the Integrated Humanist perspective, the future must be intentionally shaped through collective reasoning and compassionate policy. We must:

- Move from consumer societies to citizen societies

- Replace competition for survival with collaboration for flourishing

- Redesign systems to support the dignity of all persons, not just the interests of the few

Sociology offers the blueprint. Humanism provides the moral compass.

Together, they remind us: the structures we live within were built—and they can be rebuilt.

XI. Toward an Integrated Humanist Society

As we reflect on the long arc of human history—from tribal bands and ancient empires to digital economies and fragile democracies—it becomes clear that humanity is still evolving, not only biologically or technologically, but morally and socially. The enduring presence of inequality, domination, exclusion, and violence is not the product of fate, but of design. Yet so too is every advance in freedom, justice, and dignity.

To chart a better future, we need more than critique—we need a vision. This is the promise of Integrated Humanism: a worldview that joins the insights of anthropology and sociology with the ethical imperatives of human rights, democratic participation, and planetary responsibility.

A. The Principles of Integrated Humanism

An Integrated Humanist society is guided by core values:

- Human Dignity is Universal

Every person, regardless of origin, identity, or ability, possesses intrinsic worth. - Diversity is a Strength

Cultural, intellectual, and social differences are not obstacles—they are resources for collective problem-solving and growth. - Truth Must Serve Justice

Scientific knowledge and sociological insight must not be used to manipulate or divide, but to liberate, inform, and uplift. - Ethics are Global

In a connected world, moral responsibility extends beyond borders—to ecosystems, future generations, and all sentient beings. - Systems Can Be Redesigned

Institutions that perpetuate harm are not sacred; they can and must be restructured for equity and inclusion.

B. Applying Anthropology and Sociology for Change

Integrated Humanism calls for applied social science—bridging academia, activism, and policymaking to create societies that are more just and resilient.

Anthropology helps us:

- Understand and respect cultural diversity

- Preserve indigenous knowledge systems

- Challenge ethnocentrism and cultural imperialism

Sociology helps us:

- Diagnose systemic injustice

- Design inclusive institutions

- Empower communities through education and organization

Together, these disciplines become tools for designing humane systems—in education, governance, health, labor, and media.

C. The Road Ahead: From Hierarchy to Partnership

The ultimate goal of an Integrated Humanist society is not to erase difference or flatten identity—but to replace domination with partnership.

This means:

- Shifting from competitive hierarchies to cooperative networks

- Empowering local voices while building global solidarity

- Embracing evidence-based policy grounded in ethical reasoning

- Cultivating civic education that promotes critical thinking and compassion

It also means acknowledging history—its traumas and triumphs—and using that knowledge to heal, rebuild, and reimagine.

D. Conclusion: Rewriting the Human Story

We began with two questions: What does it mean to be human? And how do we live together?

Anthropology and sociology show us that there is no single answer. But Integrated Humanism offers a response: we live together best when we honor each other’s dignity, learn from one another’s stories, and design societies that serve the whole of humanity—not just its most powerful fragments.

A better world is not a utopian fantasy. It is the next chapter of the human story, waiting to be written—by minds that are open, hearts that are courageous, and communities that are united in purpose.