Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Atom’s Promise and Peril

An overview of nuclear power’s dual legacy and human responsibility - From Alchemy to Atom: A History of Nuclear Discovery

The Scientific Origins of Nuclear Power - Inside the Reactor: The Science of Nuclear Energy Today

How Nuclear Power Works and What Scientists Are Doing Now - From Submarines to Skylines: Uses and Sources of Nuclear Power

Nuclear Energy in Power Generation, Medicine, and Industry - Global Map of the Atom: Major Nuclear Sites and Facilities

Laboratories, Reactors, and International Landmarks - Bombs and Balances: Nuclear Power in National Security

Deterrence, Proliferation, and the Nuclear Dilemma - Governing the Atom: National and International Law

Frameworks for Regulation, Safety, and Non-Proliferation - The Integrated Humanist Approach to Nuclear Power

Science, Ethics, and Global Stewardship - Conclusion: The Splitting Point

Choosing between the atom’s destructive past and its constructive future

Introduction: The Atom’s Promise and Peril

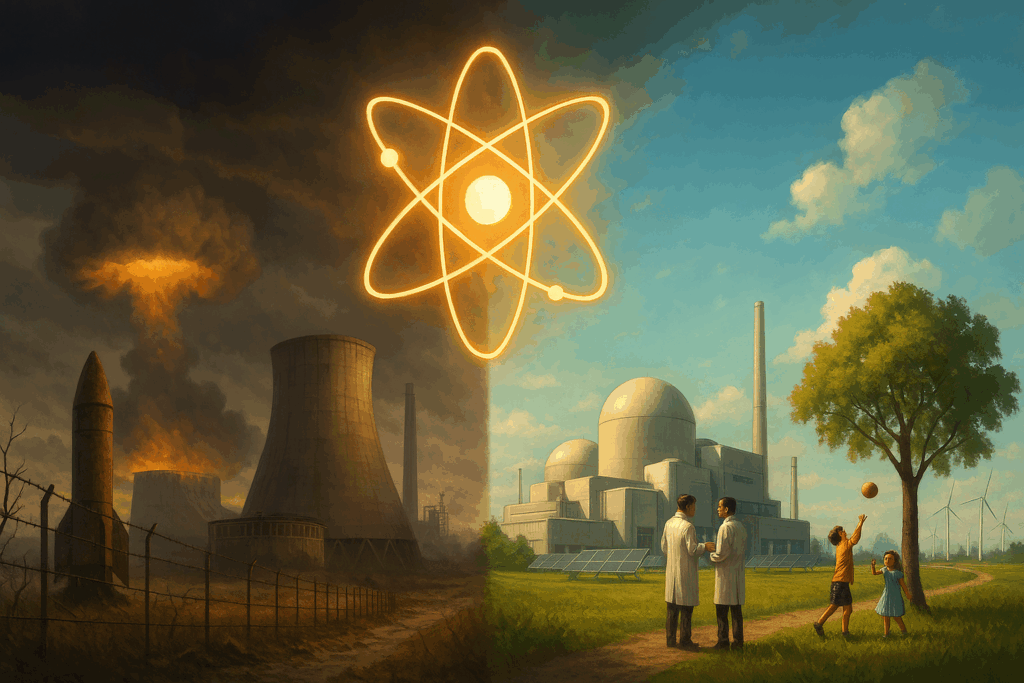

Of all the forces harnessed by human science, none has provoked such a volatile mix of awe, fear, and ambition as nuclear power. It is a force born in the heart of the atom, a substance invisible to the eye yet capable of reshaping the world—destroying entire cities or lighting them for decades. Since the splitting of the atom in the early 20th century, nuclear science has become one of the most transformative and controversial fields in human history.

The story of nuclear power is a study in duality. Its discovery emerged from pure scientific curiosity—researchers seeking to understand the fundamental nature of matter. Yet it was almost immediately swept into the machinery of war, leading to the creation of the most destructive weapons ever devised. In the wake of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, nuclear energy was rebranded as a force for peace, offering the promise of nearly limitless, carbon-free electricity. But that promise has remained entangled in complex realities: deadly accidents, political secrecy, radioactive waste, and geopolitical tensions.

Today, as the world faces a mounting climate crisis and searches for cleaner and more efficient sources of energy, nuclear power has returned to the global spotlight. But this time, it stands at a critical inflection point. Advances in reactor safety, waste recycling, and fusion research offer hope for a new generation of nuclear technology—if society is willing to pursue it with both courage and caution.

This article explores the full spectrum of nuclear power: from its origins in early scientific exploration to its current uses in medicine, industry, and national security; from the locations of nuclear laboratories and plants to the international laws governing their use. Most importantly, it proposes a new way forward—a vision of nuclear energy guided not by fear or ideology, but by the principles of Integrated Humanism: science, ethics, transparency, and global responsibility.

1. From Alchemy to Atom: A History of Nuclear Discovery

The Scientific Origins of Nuclear Power

The path to nuclear power began not in a laboratory, but in the ancient imagination. For millennia, alchemists and philosophers speculated about the fundamental building blocks of nature. They believed in hidden energies within matter—forces that could transmute lead into gold or unlock eternal life. While their theories were mystical and often misguided, the underlying intuition was profound: matter contains unseen power.

The scientific revolution transformed these dreams into systematic inquiry. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, physicists began to uncover the invisible structure of the atom. Wilhelm Röntgen discovered X-rays in 1895. Henri Becquerel soon found natural radioactivity in uranium salts, and Marie and Pierre Curie isolated the highly radioactive elements polonium and radium. These early pioneers risked their lives to understand a force that had no precedent in classical physics.

The first theoretical breakthrough came with Ernest Rutherford’s model of the atom and his experiments revealing the nucleus—a dense, positively charged core. Then came Niels Bohr’s quantum model, refining our understanding of electron orbits and atomic energy levels. But the real turning point arrived in 1938, when German physicists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann discovered nuclear fission: the splitting of an atom’s nucleus, which released a massive amount of energy. Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch interpreted the phenomenon, and word spread rapidly through the international scientific community.

This discovery triggered a race. Physicists understood that if a fission chain reaction could be controlled or amplified, it might unleash unprecedented power. In 1939, Albert Einstein and physicist Leo Szilard co-authored a letter to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, warning that Nazi Germany might develop a nuclear weapon. That letter led to the formation of the Manhattan Project: a massive, secret U.S. government research program that culminated in the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

After the war, the potential of nuclear energy was reimagined. President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Atoms for Peace speech in 1953 sought to shift public perception, promising a future where nuclear technology would serve medicine, agriculture, and energy rather than warfare. Civilian nuclear power plants emerged in the 1950s and ’60s, from the Obninsk reactor in the Soviet Union to the Shippingport Atomic Power Station in the U.S.

Yet nuclear science never fully shook its association with existential threat. The Cold War deepened the arms race. Protests against nuclear testing grew, especially after environmental and health impacts became undeniable. And while peaceful reactors multiplied, accidents at Three Mile Island (1979), Chernobyl (1986), and Fukushima (2011) reawakened global fears.

Still, through every boom and backlash, nuclear science has advanced. It has provided some of the cleanest baseload electricity on Earth, extended human lifespans through medical applications, and probed the outer edges of physics through high-energy research. The atom’s story is far from over—it is a tale of promise still unfolding.

2. Inside the Reactor: The Science of Nuclear Energy Today

How Nuclear Power Works and What Scientists Are Doing Now

At the heart of a nuclear power plant is a paradox: to create usable energy, we split the very particles that make up matter itself. The principle is elegant and devastatingly powerful. Nuclear fission—the process of splitting heavy atomic nuclei—releases energy as heat, which is then converted into electricity. But how this process is controlled, contained, and improved is the true art of nuclear engineering.

In a standard nuclear reactor, uranium-235 or plutonium-239 isotopes serve as fuel. When struck by a neutron, a fissile atom splits, releasing more neutrons and a burst of energy. These neutrons then strike other atoms, creating a sustained chain reaction. The resulting heat boils water into steam, which drives turbines and generates electricity—just like in a fossil fuel plant, but without combustion or carbon emissions.

Control rods made of neutron-absorbing materials like boron or cadmium regulate the reaction. Cooling systems—typically using water, liquid metal, or gas—prevent overheating, and a containment structure shields the surrounding environment. Every step is governed by rigorous layers of safety engineering.

Advances in Reactor Design

The earliest reactors—pressurized water reactors (PWRs) and boiling water reactors (BWRs)—still dominate the global fleet, but nuclear science has moved far beyond these mid-20th century models.

Today’s Generation III+ reactors offer significant safety improvements. They are designed to passively shut down and cool themselves without human intervention or external power, a feature born from hard lessons at Fukushima. Meanwhile, Generation IV designs, currently in development, aim to reduce waste, increase fuel efficiency, and offer inherent safety through new materials and configurations, such as:

- Molten Salt Reactors (MSRs) – using liquid fuel that operates at low pressure

- Gas-Cooled Fast Reactors (GFRs) – operating at high temperatures for industrial heat applications

- Lead-cooled or Sodium-cooled Fast Reactors – allowing for rapid neutron economy and waste recycling

Another promising advancement is the Small Modular Reactor (SMR). These compact units can be built in factories, shipped to remote locations, and scaled flexibly. Countries like Canada, the UK, and the U.S. are exploring SMRs as a safer, more adaptable nuclear solution.

The Quest for Fusion

The holy grail of nuclear science is fusion—combining light atomic nuclei (like hydrogen isotopes) into heavier ones, releasing even more energy than fission and with no long-lived radioactive waste. Fusion powers the sun, and replicating it on Earth would offer virtually unlimited clean energy.

Projects like ITER (International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor) in France, the National Ignition Facility in the U.S., and a wave of private startups are racing to achieve net energy gain—where a fusion reactor produces more energy than it consumes. Recent breakthroughs, such as laser-driven ignition and high-temperature superconductors, have brought fusion closer to reality than ever before.

Beyond Energy: Medicine, Industry, and Research

Nuclear technology extends beyond electricity. Radioisotopes produced in nuclear reactors are essential in medical imaging (e.g., PET scans, SPECT), radiation therapy for cancer, and sterilization of medical equipment. Nuclear techniques are also used in archaeology (carbon dating), agriculture (mutation breeding), and industrial inspection (radiographic testing of welds).

High-energy physics facilities like CERN push the boundaries of knowledge about matter, antimatter, and the origins of the universe—demonstrating that nuclear science is not only about energy, but about understanding existence itself.

3. From Submarines to Skylines: Uses and Sources of Nuclear Power

Nuclear Energy in Power Generation, Medicine, and Industry

When most people think of nuclear power, they imagine a sprawling reactor complex feeding electricity into the grid. But the reach of nuclear technology is far broader and more diverse than energy production alone. From powering military vessels to diagnosing cancer, the atom’s power has become deeply embedded in modern civilization.

Electricity Generation: The Backbone of Civilian Nuclear Power

The primary civilian use of nuclear energy is electrical power. As of 2025, over 440 nuclear reactors operate in 30+ countries, providing around 10% of the world’s electricity—and over 70% in nuclear-reliant countries like France. These plants generate energy continuously, unlike intermittent sources like solar or wind, making them critical providers of baseload power.

Most of these plants use uranium fuel, but interest is growing in thorium, a more abundant element with potential advantages in safety and waste reduction. Uranium-235 is the standard fuel in light-water reactors, enriched to increase its fissionability. The fuel cycle—from mining to enrichment, use, and disposal—is a tightly regulated global process.

Naval and Aerospace Propulsion

Nuclear power revolutionized maritime strategy in the mid-20th century. Nuclear submarines and aircraft carriers, powered by compact onboard reactors, can remain at sea for months without refueling. This strategic advantage has become central to major naval powers, including the U.S., Russia, China, France, and the UK.

In space, nuclear energy has powered long-range probes such as Voyager 1 and 2 and Curiosity and Perseverance rovers on Mars, using Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs) that convert heat from plutonium-238 decay into electricity. Future deep space missions may rely on small-scale fission or fusion systems to sustain life support and propulsion far from the Sun.

Nuclear Medicine and Radiological Science

One of the most humanitarian applications of nuclear science lies in nuclear medicine:

- Diagnostic tools such as PET scans (using fluorine-18) and SPECT scans provide real-time imaging of biological function.

- Radiation therapy targets and destroys cancer cells using cobalt-60, cesium-137, or linear accelerators.

- Sterilization of medical equipment with gamma radiation ensures hygiene in surgical and dental tools without heat or chemicals.

Nuclear science has also enabled radiotracer studies, biochemical research, and neuroscience applications that deepen our understanding of the human body.

Industrial and Agricultural Uses

In industry, nuclear technology is used for:

- Radiographic inspection of welds and structures

- Irradiation of food to eliminate pathogens and pests without cooking

- Measurement of fluid flow, material density, and moisture content

In agriculture, induced mutation via radiation has been used to develop hardier crop strains, and isotope tagging helps track water movement in soils.

Sources of Nuclear Fuel

The vast majority of nuclear reactors use enriched uranium, mined primarily in Kazakhstan, Canada, Australia, and Namibia. The fuel undergoes a complex process of milling, conversion, enrichment, and fabrication into fuel rods.

Thorium, an alternative fuel, is more abundant and potentially safer, producing fewer long-lived radioactive byproducts. However, it is not yet widely used due to limited infrastructure and investment.

Plutonium-239, a byproduct of uranium reactors, can be used as a fuel in MOX (Mixed Oxide) fuel and fast breeder reactors, though it carries significant proliferation risks.

4. Global Map of the Atom: Major Nuclear Sites and Facilities

Laboratories, Reactors, and International Landmarks

Nuclear science is not confined to textbooks and theory—it lives in physical infrastructure, spread across the globe in reactors, research labs, weapons facilities, and regulatory institutions. The geography of nuclear power tells a story of national priorities, scientific ambition, and geopolitical influence.

Major Nuclear Power-Producing Countries

As of 2025, the top producers of nuclear electricity are:

- United States – Home to over 90 reactors, mostly aging Generation II designs, but also a leader in Small Modular Reactor (SMR) development and reactor life extension.

- France – The most nuclear-dependent country in the world, generating over 70% of its electricity from nuclear, with cutting-edge safety and recycling programs.

- China – Rapidly expanding its nuclear fleet with both domestic and imported reactor designs, and a major investor in fusion and thorium.

- Russia – A nuclear superpower with military and civilian reactors, fast breeder programs, and international reactor export deals.

- South Korea – Known for efficient and reliable reactor operation, and a key player in global nuclear construction and design.

- India – Developing both uranium and thorium programs, with a focus on energy independence and closed fuel cycles.

Other countries with significant programs include Canada, the UK, Ukraine, Japan (restarting post-Fukushima), and Sweden.

Key Research Laboratories and Institutions

- CERN (Switzerland/France) – Though known for particle physics, CERN’s research intersects with nuclear science at the deepest level, exploring matter, energy, and antimatter.

- Los Alamos National Laboratory (USA) – Birthplace of the atomic bomb and now a center for nuclear security, materials science, and national defense technologies.

- Oak Ridge National Laboratory (USA) – A leader in reactor materials research, isotope production, and advanced modeling of nuclear processes.

- Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR, Russia) – An international research center for nuclear physics and particle studies.

- ITER (France) – The world’s largest fusion experiment, an international collaboration aiming to prove the viability of fusion as a power source.

Disaster and Decommissioned Sites

- Chernobyl (Ukraine) – Site of the 1986 reactor explosion, now a sealed-off exclusion zone and symbol of both failure and ecological curiosity.

- Fukushima Daiichi (Japan) – Severely damaged by a tsunami in 2011, with ongoing cleanup and decommissioning efforts.

- Three Mile Island (USA) – The most serious U.S. nuclear accident (1979), which led to major safety reforms but no confirmed casualties.

These sites serve as reminders of the importance of risk management, technological redundancy, and emergency preparedness.

International Agencies and Oversight

- IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency) – Based in Vienna, the IAEA promotes peaceful use of nuclear energy, implements safeguards, and conducts inspections to prevent weapons proliferation.

- CTBTO (Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization) – Oversees a global monitoring system to detect underground nuclear explosions.

- NRC (U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission) – Sets standards for reactor licensing, safety, and environmental protection in the United States.

Regional organizations and national regulatory bodies also enforce safety, research compliance, and waste handling rules, creating a layered system of oversight.

5. Bombs and Balances: Nuclear Power in National Security

Deterrence, Proliferation, and the Nuclear Dilemma

No other form of energy straddles the line between progress and annihilation as starkly as nuclear power. While nuclear energy can illuminate cities and heal bodies, its most fearsome potential remains tied to war. The same physics that powers reactors can be redirected into bombs. This dual-use nature gives nuclear science a central role in questions of national and global security.

Nuclear Weapons and Strategic Doctrine

Since the detonation of the first atomic bombs in 1945, nuclear weapons have redefined the very concept of war. The Cold War’s geopolitical chessboard was dominated by the logic of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD)—the idea that if two nuclear powers engage in direct conflict, both will be annihilated, deterring war through the promise of devastation.

Today, the nine known nuclear-armed states—United States, Russia, China, France, United Kingdom, India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea—possess an estimated 12,000 nuclear warheads. These range from massive intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) to low-yield tactical nukes. Nations develop nuclear triads—land, air, and sea-based delivery systems—to ensure second-strike capability even after a surprise attack.

Though no nuclear weapon has been used in war since 1945, the threat endures. Periodic escalations—such as missile tests by North Korea or brinkmanship between India and Pakistan—remind the world how fragile nuclear peace truly is.

Proliferation and the Challenges of Control

The spread of nuclear weapons, or proliferation, remains one of the most pressing global security concerns. Civilian nuclear programs can, under certain conditions, be redirected toward weapons development. Enriched uranium and separated plutonium—both essential for nuclear power—are also key ingredients for bombs.

The Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), signed by 191 countries, seeks to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons while allowing for peaceful nuclear development. Yet enforcement is difficult. Nations like Iran and North Korea have tested the boundaries of international oversight, using civilian programs as a cover for clandestine weapons ambitions.

The global community has responded with inspections, sanctions, and diplomatic frameworks. The IAEA plays a crucial role in verifying compliance, but its authority depends on international cooperation and political will.

Security of Civilian Facilities

Beyond weapons, civilian nuclear sites themselves can be targets of terrorism, sabotage, or cyberattack. The 2022 occupation of the Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant in Ukraine during wartime highlighted the dangers of military activity around civilian reactors. The specter of a nuclear incident triggered not by technical failure but by conflict remains a serious risk.

Cybersecurity has also emerged as a priority, with reactor control systems increasingly vulnerable to sophisticated hacking—potentially leading to shutdowns, data leaks, or even reactor compromise.

Disarmament and the Hope for Reduction

Many civil society organizations and global leaders continue to advocate for total disarmament. Treaties like New START, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, and various regional nuclear-weapon-free zones attempt to roll back arsenals and shift international norms away from dependence on nuclear deterrence.

However, as long as nuclear weapons confer perceived strategic advantages, the pressure to retain or develop them remains strong—especially for nations with security vulnerabilities or global aspirations.

6. Governing the Atom: National and International Law

Frameworks for Regulation, Safety, and Non-Proliferation

Because of its immense potential for both benefit and harm, nuclear power exists under one of the most tightly regulated legal frameworks in the world. From mining and enrichment to reactor operation and weapons restrictions, every stage of the nuclear process is subject to national law, international treaty, and institutional oversight. These legal mechanisms aim to balance innovation with security, sovereignty with shared responsibility.

National Regulation and Licensing

Each nuclear-capable country maintains a specialized authority responsible for overseeing civilian nuclear power:

- United States: The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) licenses reactors, enforces safety protocols, and regulates waste management.

- France: The Autorité de Sûreté Nucléaire (ASN) supervises reactor safety, public health, and transparency.

- India: The Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB) governs nuclear materials and facilities.

- Russia: Rostekhnadzor handles licensing, inspection, and nuclear safety standards.

These agencies enforce laws related to site approval, reactor design, employee training, environmental impact, radiation protection, and emergency planning. In democracies, many of these regulations are subject to public review and legislative approval, while in centralized regimes, decisions may be taken unilaterally.

The International Legal Architecture

The international legal regime for nuclear power rests on a complex web of treaties, conventions, and monitoring agencies.

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT)

Signed in 1968 and entered into force in 1970, the NPT is the cornerstone of global nuclear governance. It rests on three pillars:

- Non-proliferation – Preventing the spread of nuclear weapons.

- Disarmament – Gradual reduction of nuclear arsenals.

- Peaceful use – Promoting nuclear technology for civilian purposes under safeguards.

The treaty recognizes five official nuclear-weapon states (U.S., Russia, China, UK, France) and requires others to refrain from acquiring nuclear arms in exchange for access to peaceful technology.

International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)

Based in Vienna, the IAEA operates as both a watchdog and a facilitator. It inspects nuclear facilities, verifies compliance with safeguard agreements, provides technical assistance, and promotes nuclear safety and security standards.

Other Key Agreements and Bodies

- Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT): Prohibits all nuclear explosions; not yet in force due to lack of full ratification.

- Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG): Controls the export of nuclear materials and technology to prevent proliferation.

- Convention on Nuclear Safety: Sets international safety standards for nuclear power plants.

- Joint Convention on the Safety of Spent Fuel Management: Governs long-term waste handling and disposal.

Nuclear Waste and Liability Law

Radioactive waste presents one of nuclear energy’s most persistent challenges. National laws regulate:

- Temporary storage and long-term repositories (e.g., Finland’s Onkalo project)

- Transportation and security of nuclear materials

- Decommissioning of aging reactors

Legal liability for nuclear accidents varies. The Paris Convention, Vienna Convention, and Price-Anderson Act (U.S.) outline frameworks for compensation and responsibility in the event of a nuclear incident. Most laws place primary liability on the plant operator, backed by government-supported insurance pools.

Legal Debates and the Ethics of Equity

Some of the most pressing legal and moral debates in nuclear policy center around:

- Access to nuclear technology: Should poorer nations have equal rights to nuclear energy development?

- Weapon-state privilege: Is it just for a few nations to retain nuclear weapons while denying others?

- Climate vs. risk: Should environmental urgency override traditional safety and proliferation concerns?

The tension between national sovereignty and global oversight remains unresolved, and will shape the future of nuclear governance.

7. The Integrated Humanist Approach to Nuclear Power

Science, Ethics, and Global Stewardship

Nuclear power is a tool—neither inherently good nor evil. It can illuminate cities or obliterate them. It can heal the sick or poison the land. The difference lies not in the atom itself, but in the values, systems, and intentions that govern its use. An Integrated Humanist approach asks a fundamental question: What is the purpose of our power? And it answers—to serve life, truth, peace, and the common good.

Balancing Innovation with Responsibility

Nuclear technology must be guided by wisdom as much as by scientific expertise. Integrated Humanism recognizes that:

- Clean, reliable energy is essential for economic development and climate action.

- Catastrophic accidents and weapons use are morally unacceptable and must be engineered out of the system.

- Transparent governance and public oversight are not luxuries, but ethical necessities.

Thus, a humanist approach embraces the scientific promise of nuclear power while insisting on:

- Strict safety standards

- Open access to information

- Publicly accountable regulation

- Investment in fail-safe technologies

This does not mean rejection of nuclear power—but it does mean rejecting secrecy, arrogance, and unchecked nationalism in its use.

Nuclear Energy and Climate Justice

As the world accelerates toward ecological tipping points, nuclear energy may play a vital role in the global shift away from fossil fuels. Unlike coal and gas, nuclear plants produce virtually no greenhouse gas emissions during operation. They can also stabilize electrical grids and support renewable energy through dependable baseload capacity.

But Integrated Humanism also considers intergenerational and international equity:

- Are we building a system that benefits all humanity—not just the wealthiest nations?

- Are we solving today’s energy needs without burdening future generations with waste and risk?

- Can we include marginalized communities in decisions that affect their land, health, and livelihoods?

True energy justice means extending clean, safe nuclear power where it is needed—without creating new forms of dependency, exploitation, or environmental injustice.

Global Peace and Scientific Solidarity

The Integrated Humanist worldview calls for an end to the contradiction between nuclear science and nuclear war. It affirms that:

- Weapons of mass destruction have no place in a moral civilization.

- Scientific cooperation must replace arms races and technological hoarding.

- Disarmament is not idealism—it is the necessary outcome of a sane global ethic.

International treaties, fusion research partnerships, and peaceful nuclear aid should be expanded and supported as instruments of planetary solidarity—not manipulated as geopolitical tools.

Educating the Next Generation

Nuclear literacy should be part of every science and civic curriculum. Understanding the atom is part of understanding our responsibility as a species. Students, citizens, and leaders alike must learn:

- How reactors work

- What safety means

- Why non-proliferation matters

- What role nuclear energy can play in solving the climate crisis

Only through education can we cultivate a public that neither blindly fears nor blindly worships the atom—but understands it with clarity and conscience.

Conclusion: The Splitting Point

Nuclear power is not just a technological choice—it is a moral crossroads. At the center of every reactor core, every fusion experiment, and every warhead lies a single question: What will we do with the power we have?

Humanity stands at a splitting point. One path leads toward fear, secrecy, arms races, accidents, and the unchecked hunger for dominance. The other leads toward light—literally and metaphorically: clean energy, global cooperation, disarmament, and a civilization mature enough to wield the atom with wisdom.

The atom is indifferent to our values. It will split when struck. It will burn if guided. It will poison if misused. But we are not indifferent. We have a choice. We can rise to the challenge of governing this power as stewards—not as masters or slaves to its potential.

In an age where climate instability, energy insecurity, and global inequality define the human condition, nuclear science offers tools that could help us survive—and even flourish. But only if they are handled with humility, rigor, and compassion.

Integrated Humanism does not accept simplistic answers. It does not blindly champion or reflexively reject nuclear energy. Instead, it insists that our science must be integrated with our ethics, our progress with our peace, and our future with our collective responsibility to one another and to the Earth.

The splitting of the atom was one of humanity’s most extraordinary achievements. What comes next will determine whether it is also our most redeeming.