Table of Contents

- Introduction

Why Naval Power Matters - Section 1: The Origins of Seacraft

From Dugout Canoes to Viking Longships - Section 2: The Age of Sail and Exploration

Galleons, Gunpowder, and Global Expansion - Section 3: Steam and Steel – The Industrial Revolution at Sea

From Frigates to Dreadnoughts - Section 4: Modern Naval Engineering and Ship Science

Submarines, Supercarriers, and Autonomous Ships - Section 5: Naval Strategy and Global Power

Ports, Patrols, and Projection - Section 6: The Most Powerful Ships Today

Global Navies and Their Flagships - Section 7: International Law of the Sea

Sovereignty, Shipping, and Security - Section 8: Naval Power and Human Values

An Integrated Humanist Perspective

Introduction: Why Naval Power Matters

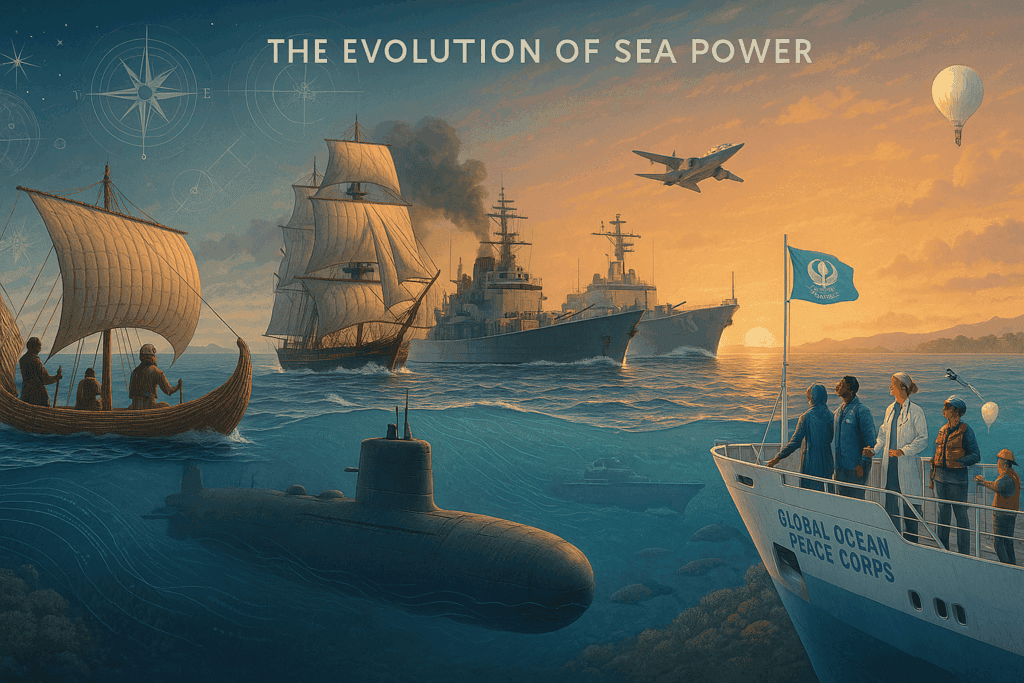

For as long as humans have gazed out over the horizon, the sea has called to us with a mixture of promise and peril. From the first lashed-together rafts that carried ancient migrants down rivers and across straits, to the nuclear-powered leviathans that now silently patrol the ocean depths, naval power has shaped the trajectory of civilization. The world’s oceans, covering more than 70% of the Earth’s surface, have been at once barriers and bridges—obstacles to be overcome, and avenues for exploration, trade, conquest, and cooperation.

Naval power is more than just a matter of military might. It is the technological mastery of an unforgiving environment. It is the science of keeping a floating city stable through waves and storms. It is the political control of sea lanes that determine global commerce and security. It is also, increasingly, an ethical question: Will our navies be guardians of peace and environmental stewardship—or instruments of domination?

In this article, we explore the history and science of seafaring and naval development—from ancient canoe and sail technology to the rise of steel supercarriers and nuclear submarines. We’ll examine how strategic naval power influenced the rise and fall of empires, how the laws of physics determine what can float and how fast it can move, and how international law tries (and often fails) to keep peace on the high seas. Finally, we will propose an Integrated Humanist perspective on the future of naval power: one that imagines cooperation, shared stewardship of the oceans, and the transformation of warships into vessels of peace, science, and rescue.

The oceans are vast, and our responsibility toward them is even greater. Let us navigate their story—together.

Section 1: The Origins of Seacraft – Human Ingenuity and the Open Sea

From Dugout Canoes to Viking Longships

Before the sail, before the compass, before even the written word—humans took to the water.

Somewhere in prehistory, our ancestors, driven by necessity, curiosity, or the hunger for new land and food, lashed logs into rafts, hollowed trees into dugouts, and stitched reeds into buoyant bundles. These earliest seacraft mark the beginning of humanity’s relationship with the sea not as a boundary but as a highway. With them, people crossed rivers, hugged coastlines, and eventually dared to venture into open waters.

Austronesian Pioneers and Oceanic Navigation

One of the greatest early feats of human seafaring was carried out by the Austronesians. Beginning more than 3,000 years ago, they navigated thousands of miles across the Pacific and Indian Oceans in outrigger canoes. Using the stars, ocean swells, wind patterns, and bird movements, these expert sailors spread from Taiwan to Polynesia, Madagascar, and even remote Easter Island—creating the largest seaborne expansion in human history before the Age of Sail.

Their boats were marvels of balance and modular design, with outriggers for stability and sails made from plaited leaves. The science here was intuitive but profound: distributed weight for balance, flexible hulls for wave absorption, and environmental reading for direction—all without modern instruments.

Egyptians, Phoenicians, and the Birth of Maritime Trade

On the shores of the Mediterranean, the ancient Egyptians crafted papyrus boats and later wooden ships to navigate the Nile and trade along the coast. The Phoenicians, famed shipbuilders and traders of the Levant, developed robust multi-oared ships for long-distance travel and commerce. Their innovations in ship design and celestial navigation laid foundations for Mediterranean naval power.

The Greeks and Triremes: Naval Warfare Emerges

By the classical era, the Greeks introduced the trireme—a sleek warship powered by three tiers of oarsmen. These ships combined speed, maneuverability, and ramming power, reflecting not just engineering but the emergence of tactical naval warfare. Battles like Salamis (480 BCE), where the outnumbered Greeks used agility and geography to defeat the Persians, showcased the strategic potential of seacraft.

The Viking Longship: Mastery of Rivers and Oceans

In northern Europe, the Vikings created longships—narrow, shallow-draft vessels that could cross the open sea yet navigate inland rivers. Their clinker-built hulls overlapped wooden planks for strength and flexibility, allowing them to absorb wave shock without breaking. The Vikings’ maritime mobility allowed them to raid, trade, and settle from North America to Russia.

From the first log raft to the complex warship, the history of early seacraft is a history of creative problem-solving in the face of nature’s most unpredictable element. These inventions didn’t just allow humans to survive; they allowed us to connect, migrate, and begin shaping the global map. As we turn toward the next era—when wind and gunpowder ruled the waves—we see how mastery of the sea became the key to empire.

Section 2: The Age of Sail and Exploration

Galleons, Gunpowder, and Global Expansion

If the ancient world saw the birth of seafaring, the Age of Sail was its adolescence—bold, unpredictable, and driven by insatiable ambition. From the 15th to the 18th centuries, sail-powered vessels carried explorers, colonists, missionaries, and navies across the globe, remapping the world and redrawing the destinies of countless civilizations.

The Science of Sailing: Harnessing the Wind

Sailing represented a leap forward in marine engineering and environmental science. By converting wind into directional propulsion, sailors could travel farther, faster, and with fewer rowers. The design of sails, rigging, and hulls evolved in tandem with the understanding of wind currents, atmospheric pressure, and fluid dynamics.

Lateen sails, first popularized in the Arab world, allowed for tacking against the wind—a crucial innovation for exploration. Caravels, used by the Portuguese and Spanish, featured mixed-rig sail systems that provided both speed and maneuverability. These advances reflected a deeper scientific engagement with natural forces, even if much of it remained trial-and-error.

Maritime Empires and Naval Supremacy

Portugal and Spain were the first to launch global maritime empires. Armed with ships like the nao and the galleon, they established colonial footholds from Africa to Asia to the Americas. These ships could carry massive cargoes and bristled with cannons—combining trade, colonization, and violence in a single floating package.

Soon after, Britain, France, and the Netherlands joined the race, and their naval strength became inseparable from their imperial ambitions. Merchant ships and warships alike became tools of economic domination, spreading language, religion, disease, and revolution around the globe.

Naval supremacy required more than ships. It demanded maps, timekeeping, and a growing scientific understanding of the Earth. The development of the marine chronometer in the 18th century allowed navigators to determine longitude accurately—a revolutionary breakthrough that helped prevent shipwrecks and ensured precise global navigation.

Weapons at Sea: The Rise of Naval Gunpowder

Cannons and gunports changed the nature of sea battles. Galleons were equipped with broadside batteries that could devastate enemy ships from a distance. Naval warfare began to prioritize firepower over boarding, turning ships into floating fortresses.

Naval engagements like the Spanish Armada (1588) and the Battle of Lepanto (1571) marked key turning points in military history, demonstrating that whoever commanded the sea could command the world.

The Dutch Fluyt and British East Indiaman: Trade Over War

Not all advancements were militaristic. The Dutch fluyt was designed for trade efficiency, with a wide hull for cargo and minimal crew needs. The British East Indiaman, a hybrid between warship and merchantman, enabled England to dominate the lucrative spice and textile routes of Asia.

These innovations also gave rise to maritime corporations, stock exchanges, and insurance systems—making naval power not just a matter of ships and sails, but of global capital.

The Age of Sail transformed oceans into global highways of commerce and conquest. It was a time of dazzling exploration—and deep exploitation. Scientific understanding of wind, time, and navigation fused with political and economic ambition, setting the stage for a new phase of naval power: the age of steam, steel, and total war.

Section 3: Steam and Steel – The Industrial Revolution at Sea

From Frigates to Dreadnoughts

The Industrial Revolution did not stop at the water’s edge—it transformed the oceans. As steam displaced sail and steel replaced wood, naval power underwent a dramatic technological acceleration. Ships became faster, larger, and deadlier. The age of heroic captains and wind-filled sails gave way to an era of engineers, engines, and global mechanized warfare.

The Advent of Steam Power

The early 19th century saw the first practical steamships, equipped with paddle wheels and later with screw propellers. These vessels were no longer dependent on wind, making them more reliable in both war and commerce. Steamships could travel upriver, against the wind, and on tighter schedules—revolutionizing global trade and naval logistics.

The science of thermodynamics now took center stage. Engineers began calculating boiler pressure, fuel efficiency, and mechanical output. The transition from wood-fired to coal-fired boilers created a need for coaling stations around the world, laying the infrastructure for global empires.

Ironclads and the Rise of Armored Warships

The 1850s and 1860s introduced a new beast to the oceans: the ironclad. These warships, clad in metal armor, could shrug off cannon fire that would have shredded wooden hulls. The most famous early clash between ironclads was the 1862 Battle of Hampton Roads in the American Civil War, where the USS Monitor and the CSS Virginia dueled to a draw—marking the end of the wooden warship era.

European navies quickly adopted ironclad designs, sparking a new arms race in shipbuilding. Naval power became a measure of industrial capacity.

From Battleship to Dreadnought

The pinnacle of pre-WWI naval design was the battleship. These floating fortresses carried large-caliber guns and thick armor, designed to dominate open-sea engagements. The British HMS Dreadnought, launched in 1906, set a new standard: it was faster, more heavily armed, and entirely turbine-powered.

The Dreadnought sparked a global revolution. Every navy scrambled to match its design, triggering a pre-war naval arms race, especially between Britain and Germany. Naval science became national strategy. Precision ballistics, advanced metallurgy, gunnery mathematics, and new propulsion technologies all became critical military secrets.

The Submarine: Silent and Deadly

While surface ships ruled the waves, a more elusive threat began to stir below: the submarine. Though experimental versions existed earlier, it was in World War I that the submarine—powered by diesel engines and armed with torpedoes—proved its worth as a stealth weapon.

The science of underwater navigation, buoyancy control, and pressure hulls advanced quickly. Submarines became more sophisticated in WWII, with sonar, radar detection, and even the first electric propulsion systems. Their strategic role expanded from ship-sinking to intelligence, reconnaissance, and eventually nuclear deterrence.

Naval Power in the World Wars

Naval forces played pivotal roles in both World Wars. In WWI, British blockades strangled German supply lines. In WWII, massive carrier battles in the Pacific—like Midway—replaced the old model of ship-to-ship combat with aircraft-launched strikes over hundreds of miles.

Aircraft carriers, not battleships, would ultimately become the new kings of the sea.

The industrialization of naval power rewrote the rules of sea warfare. No longer romantic or regional, it became scientific, global, and devastating. The ship was now an engine of empire and annihilation. But even as navies reached their destructive zenith, a new revolution was already underway—one that would merge the mechanical with the digital, the strategic with the nuclear.

Section 4: Modern Naval Engineering and Ship Science

Submarines, Supercarriers, and Autonomous Ships

Today’s naval vessels are more than ships—they are floating ecosystems of technology, crewed cities, and complex combat systems operating on, above, and beneath the sea. The science that governs them is interdisciplinary: part physics, part materials engineering, part artificial intelligence, and part global geopolitics. In the modern era, engineering precision defines maritime dominance.

The Physics of Staying Afloat

Even the mightiest warships obey a humble principle: Archimedes’ law of buoyancy. A ship floats because it displaces a volume of water equal to its own weight. Designing a modern hull means optimizing that balance while resisting forces from wind, waves, and enemy fire.

Naval architects use computational fluid dynamics to model how water flows around hulls, reducing drag and increasing speed and efficiency. Hulls are designed for specific missions—deep ocean, littoral combat, stealth insertion, or carrier operations.

Propulsion Systems: Powering the Beasts

- Diesel-electric engines power many submarines and mid-size vessels, offering efficiency and range.

- Gas turbines, like those found in jets, provide high-speed propulsion for destroyers and frigates.

- Nuclear power, used in aircraft carriers and submarines, offers virtually unlimited range and independence from refueling. A U.S. nuclear submarine can remain submerged for months, limited only by food and crew endurance.

Propeller design is another science in itself—some are optimized for speed, others for stealth. Quieting technologies such as skewed blades and pump-jets are crucial for submarine evasion.

Navigation and Sensing: Eyes in the Deep

Modern ships use a fusion of systems for navigation and detection:

- Radar scans the surface and airspace.

- Sonar detects underwater threats and terrain.

- Inertial guidance systems provide dead reckoning when GPS is unavailable.

- LIDAR and satellite imaging support coastal operations and remote sensing.

Submarines deploy passive sonar arrays to “listen” silently, and active sonar for locating targets—but at the risk of revealing their position.

Materials and Stealth Technology

Modern naval materials combine strength, flexibility, and stealth:

- Carbon composites reduce weight while enhancing durability.

- Radar-absorbent coatings and angled hull designs deflect detection, particularly on stealth destroyers and subs.

- Shock-resistant interiors protect crew and equipment from explosions and concussive waves.

Damage control is also science-driven: fire suppression, watertight compartmentalization, and autonomous alert systems all improve survivability.

Aircraft Carriers: Cities at Sea

The aircraft carrier is the crown jewel of modern navies. Nuclear-powered U.S. supercarriers like the Gerald R. Ford class can carry over 75 aircraft, support a crew of more than 4,000, and project air power anywhere on Earth without needing foreign bases.

Carriers require:

- Electromagnetic catapults to launch aircraft

- Arresting gear to recover them

- Advanced air traffic control and radar

- Integrated defense systems including CIWS (close-in weapon systems) and anti-missile lasers

They are protected by strike groups that include destroyers, cruisers, submarines, and logistical supply vessels.

Submarines: The Invisible Leviathans

Modern submarines are marvels of engineering:

- Ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) carry nuclear weapons, forming part of the “nuclear triad” of deterrence.

- Attack submarines (SSNs) specialize in hunting ships and other submarines.

- Diesel-electric subs are quieter in shallow waters and favored by regional navies.

Submarine warfare relies on stealth, endurance, and signal intelligence. Some subs are equipped with unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) and divers for special operations.

The Rise of Autonomous and AI-Controlled Vessels

Uncrewed surface vessels (USVs) and underwater drones are entering naval service. These platforms can patrol, mine-sweep, spy, and even strike without risking human lives. AI systems manage threat detection, target prioritization, and battlefield simulations in real time.

This transition brings both potential and peril—introducing questions of accountability, escalation, and control in automated warfare.

Modern naval science is as much about invisibility and information as it is about firepower. The sea, once conquered by strength alone, is now a domain of stealth, sensors, and satellites. But advanced ships alone don’t ensure peace. Strategy, ethics, and law are the new frontiers of maritime power.

Section 5: Naval Strategy and Global Power

Ports, Patrols, and Projection

Naval power is not just about the ships themselves—it’s about how, where, and why they are used. From deterring conflict to securing global trade, navies have become tools of both hard power and international signaling. Strategy, geography, and logistics are as important as engineering in determining a nation’s command of the seas.

The Core Concepts of Naval Strategy

Naval strategy is shaped by a handful of enduring principles:

- Sea Control: The ability to dominate a maritime area and prevent enemy use of it. This enables both military operations and commercial shipping.

- Power Projection: Using naval forces to influence events on land—via carrier-launched strikes, amphibious landings, or missile attacks.

- Deterrence: Particularly in the nuclear age, the presence of powerful naval assets (such as ballistic missile submarines) can prevent aggression through the threat of overwhelming retaliation.

- Freedom of Navigation: Ensuring that sea lanes remain open for global commerce. This principle underpins modern maritime security doctrine.

Navies enforce sovereignty, conduct surveillance, and support diplomacy through presence missions, joint exercises, and strategic posturing.

Geography as Destiny: Strategic Chokepoints

Certain narrow maritime passages serve as the pulse points of global trade and strategy:

- Strait of Hormuz: Controls access to Persian Gulf oil routes

- Strait of Malacca: A vital conduit between the Indian and Pacific Oceans

- Suez Canal & Panama Canal: Man-made shortcuts critical to global shipping

- Bosporus and Dardanelles: Gateways to the Black Sea

- English Channel and GIUK Gap: Strategic filters between the Atlantic and Europe

Control or blockade of these chokepoints can cripple economies, making them perennial flashpoints in geopolitical conflict.

The Role of Naval Bases and Global Logistics

Modern naval power depends on a global web of support:

- Major Ports and Bases: Norfolk (USA), Yokosuka (Japan), Diego Garcia (Indian Ocean), Toulon (France), and more.

- Replenishment Vessels: Supply fuel, ammunition, and food at sea, extending operational range.

- Undersea Cables and Communication Relays: Many of the world’s internet and communication channels lie under the sea, guarded (and sometimes surveilled) by navies.

Naval supremacy means not just projecting force but sustaining it.

Amphibious Warfare and Littoral Combat

Navies also operate close to shore—supporting land operations, inserting special forces, or evacuating civilians. Amphibious assault ships, like the U.S. Wasp class, serve as hybrid aircraft carriers and troop transports. Littoral Combat Ships (LCS) are designed for speed and agility in shallow waters, ideal for piracy response and coastal security.

Coalitions, Exercises, and Soft Power

Navies increasingly work together in joint exercises like RIMPAC, BALTOPS, and Malabar, building interoperability and trust among allies. Humanitarian missions—disaster relief, medical outreach, anti-piracy patrols—show how navies can project not only power but goodwill.

Naval strategy today reflects a world of interdependence, threat, and opportunity. The oceans are not just theaters of war—they are lifelines of trade, communication, and collaboration. As we explore the cutting edge of global fleets in the next section, we must remember: naval power is a mirror of national priorities—and a test of international responsibility.

Section 6: The Most Powerful Ships Today

Global Navies and Their Flagships

In today’s geopolitical landscape, a nation’s most powerful naval vessels are more than tools of war—they are floating statements of technological achievement, global influence, and national identity. Aircraft carriers, nuclear submarines, guided missile destroyers, and amphibious assault ships are the core instruments of naval dominance. This section surveys the leading fleets of the 21st century.

The United States Navy: Unmatched Global Reach

The U.S. Navy remains the world’s most powerful maritime force, with unmatched global logistics and cutting-edge ship classes.

- Gerald R. Ford-class Aircraft Carrier

The most advanced carrier in history, with electromagnetic aircraft launch systems (EMALS), enhanced radar, and a reduced crew requirement. Nuclear powered and capable of deploying over 75 aircraft, it is a mobile airbase and centerpiece of carrier strike groups. - Virginia-class Nuclear Attack Submarine

Exceptionally quiet, fast, and equipped with cruise missiles, advanced sonar, and special operations capabilities. Designed for both blue-water and littoral missions. - Zumwalt-class Destroyer

A stealth warship with an angular radar-deflecting hull, advanced automation, and the potential for railgun or laser integration.

China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN): Rising Sea Power

China has rapidly expanded its navy, surpassing the U.S. in number of vessels and focusing heavily on regional dominance and power projection.

- Shandong Aircraft Carrier

China’s first domestically built carrier, based on Soviet designs but incorporating local innovations. A third, more advanced carrier (Fujian) is under construction with electromagnetic catapults. - Type 055 Destroyer

Among the largest and most heavily armed destroyers in the world, with 112 vertical launch cells for missiles and strong radar capabilities—ideal for air defense and long-range strike. - Yuan-class Submarines

Diesel-electric submarines equipped with air-independent propulsion (AIP), allowing extended underwater operation—optimized for South China Sea patrols.

Russia: Strategic Submarines and Symbolic Surface Vessels

Though constrained by budget and sanctions, Russia maintains formidable nuclear and submarine capabilities.

- Kirov-class Battlecruiser

A relic of the Cold War modernized for current use. These massive, nuclear-powered ships carry anti-ship and anti-aircraft missiles, and remain floating symbols of prestige. - Borei-class Ballistic Missile Submarine

The foundation of Russia’s sea-based nuclear deterrent. Equipped with Bulava SLBMs (submarine-launched ballistic missiles) and designed for quiet operation. - Yasen-class Nuclear Attack Submarine

A new generation of stealthy, multi-role submarines with cruise missile capability.

United Kingdom: Agile Modernization

The Royal Navy, once the world’s greatest, has modernized around fewer but highly advanced vessels.

- Queen Elizabeth-class Aircraft Carrier

The UK’s flagship, capable of deploying F-35B stealth fighters. These carriers are interoperable with NATO navies and central to Britain’s maritime strategy. - Astute-class Submarine

Nuclear-powered, highly stealthy, and equipped with both Tomahawk cruise missiles and Spearfish torpedoes.

France, India, and Other Major Players

- France – Charles de Gaulle Aircraft Carrier

The only nuclear-powered carrier outside the U.S., forming the centerpiece of French global deployments. - India – INS Vikrant and Arihant-class Subs

India’s navy is growing rapidly, focusing on self-reliance with indigenous aircraft carriers and a developing nuclear submarine fleet. - Japan – Izumo-class Helicopter Destroyers

Technically destroyers, these are being converted to launch F-35Bs, reflecting Japan’s evolving defense posture.

Autonomous and Hypersonic Threats

Several navies are testing uncrewed surface vessels (USVs) and autonomous subs, as well as integrating hypersonic missiles—which travel at over Mach 5 and are nearly impossible to intercept. These advances will soon redefine what “power” at sea truly means.

Naval might in the 21st century is as much about networks and survivability as it is about firepower. It is a contest of intelligence, stealth, logistics, and deterrence. But with these ships also comes the question: will this technology be used to protect or to provoke?

Section 7: International Law of the Sea

Sovereignty, Shipping, and Security

The oceans are the planet’s final frontier of shared space—and the rules that govern them are essential to peace, trade, and survival. International law seeks to balance national sovereignty with the idea of the sea as a global commons. But as navies expand, shipping intensifies, and resources dwindle, disputes over maritime rights are on the rise.

UNCLOS: The Constitution of the Oceans

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)—adopted in 1982 and now ratified by most nations—defines the legal status of all parts of the sea and the seabed.

Key maritime zones established by UNCLOS:

- Territorial Waters: Up to 12 nautical miles from a nation’s baseline; considered sovereign territory.

- Contiguous Zone: Extends to 24 nautical miles; allows enforcement of customs, immigration, and pollution laws.

- Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ): Extends up to 200 nautical miles; grants exclusive rights to exploit marine resources (e.g., fishing, oil, gas).

- High Seas: Beyond all EEZs; open to all states for navigation, overflight, fishing, and research.

- Continental Shelf: Nations may claim natural prolongation of their landmass beyond the EEZ, for mineral and resource extraction.

Major Maritime Disputes

Despite legal frameworks, enforcement remains difficult—especially where power and politics collide. Notable conflicts include:

- South China Sea: Multiple overlapping claims from China, the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Brunei. China’s “Nine-Dash Line” has been ruled invalid by international arbitration, but the ruling is not enforced.

- Arctic Ocean: Melting ice opens new shipping routes and access to resources. Russia, Canada, Norway, and others compete to expand continental shelf claims.

- Eastern Mediterranean: Tensions between Turkey, Greece, Cyprus, and Israel over energy exploration in overlapping EEZs.

- Falklands and South Atlantic: Argentina and the UK maintain rival claims to surrounding maritime zones and resources.

Freedom of Navigation and Military Presence

UNCLOS protects freedom of navigation, which the U.S. and other major naval powers routinely assert through Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) in contested areas. These operations test the boundaries of sovereignty claims, often leading to diplomatic tension or confrontation.

Military use of the sea also includes:

- Anti-piracy patrols off Somalia

- Maritime surveillance of undersea cables and data infrastructure

- Submarine “cat and mouse” games in strategic chokepoints

- Naval blockades and sanctions enforcement

Maritime Law Enforcement and Cooperation

While conflict garners headlines, much of maritime law today is cooperative:

- Search and Rescue (SAR) agreements between nations

- International Maritime Organization (IMO) regulates shipping safety and environmental standards

- Joint patrols monitor illegal fishing, drug trafficking, and smuggling

- Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are expanding under shared conservation goals

Environmental Law and the Blue Planet

Modern naval and shipping activity must also address environmental stewardship:

- Ballast water dumping spreads invasive species

- Oil spills, sonar disruption of marine life, and ship collisions with whales remain major concerns

- Overfishing and deep-sea mining challenge sustainability goals

UNCLOS includes provisions for marine environmental protection, but enforcement is uneven and often dependent on political will and financial capacity.

International maritime law is an evolving framework, not a fixed reality. In practice, the balance between sovereignty, security, and shared responsibility is fragile—particularly in a warming world with rising sea levels, declining fish stocks, and intensifying strategic competition.

Section 8: Naval Power and Human Values

An Integrated Humanist Perspective

Naval power has long been a reflection of national ambition—expansion, extraction, empire, and deterrence. But in the 21st century, with climate change accelerating, oceanic ecosystems under threat, and global cooperation more essential than ever, the philosophy behind sea power must evolve. An Integrated Humanist perspective calls for a shift in priorities: from domination to stewardship, from conquest to collaboration.

The Moral Paradox of Naval Might

Today’s warships are masterpieces of science and engineering—yet they are built to destroy. Trillions are spent globally on fleets, while billions of people still lack access to clean water or basic healthcare. Submarines capable of erasing cities glide silently beneath oceans where coral reefs are bleaching and fisheries are collapsing.

This paradox raises ethical questions:

- What are navies for in a world of existential environmental threat?

- How can we justify weaponizing the ocean while failing to protect it?

- Can we imagine a navy not as an instrument of fear, but as an agent of human service?

The Positive Role of Navies: Humanitarian Potential

Integrated Humanism envisions a transformation in naval mission and design:

- Disaster Response and Evacuation: Aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships can deploy helicopters, medical teams, and desalination units—critical in typhoon, earthquake, or tsunami zones.

- Scientific and Environmental Missions: Navy vessels can host marine biologists, oceanographers, and climate researchers. Nuclear submarines can map the deep sea and monitor seismic activity.

- Peacekeeping and Rescue Patrols: Anti-piracy, search-and-rescue, anti-trafficking, and refugee interception efforts could be organized under multinational humanitarian mandates rather than national interests.

The Global Ocean Peace Corps: A New Vision

One bold proposal from the Integrated Humanist platform is the creation of a Global Ocean Peace Corps—a neutral, non-aligned fleet staffed by international volunteers, scientists, and humanitarian professionals.

Its goals would include:

- Protecting marine biodiversity and enforcing environmental law

- Assisting in refugee crises and coastal evacuations

- Supporting coastal nations during pandemics, famines, and disasters

- Monitoring illegal fishing and pollution

- Acting as a scientific and diplomatic bridge between navies

Such a force would require cooperation across borders, oversight by international organizations, and the repurposing of naval funding toward sustainability and peace.

Demilitarizing the Commons, Not Abandoning the Sea

Integrated Humanism does not call for the elimination of navies—but for a rebalancing of purpose:

- Reduce arms races and naval escalation in contested regions

- Increase transparency and joint drills between rival powers

- Redirect naval R&D toward green propulsion, fuel efficiency, and reef-safe operations

- Enshrine global oceanic stewardship in maritime education and naval academies

Oceans Without Borders

The ocean belongs to no one—but it sustains everyone. It connects every continent, feeds billions, and absorbs vast quantities of carbon dioxide. Naval power must evolve to reflect this truth: the sea is not just a space of national interest, but a shared planetary lifeline.

Conclusion: Oceans as Commons, Not Theaters of War

From the first dugout canoes to today’s nuclear-powered giants, naval power has shaped the course of humanity. It has opened new worlds—and closed others in conquest. It has embodied human ingenuity and hubris alike.

As we move deeper into the 21st century, the defining test of naval power will not be whose fleet is largest—but whose fleet serves humanity best. Can our ships heal, protect, and discover as powerfully as they once fought?

With science as our compass and human dignity as our anchor, we believe they can.