- Introduction – What Is a Drug?

Understanding how drugs affect our minds, bodies, and society - What Happens When You Take a Drug

A simple look at chemistry and the body - A Short History of Drugs

From plants and potions to modern medicine - Medicine and Healing

How prescription drugs help (and sometimes harm) - Feeling Different

Why people use recreational drugs - Addiction

How drugs hijack the brain - Rules and Reality

Who decides what’s legal? - A New Framework

Classifying drugs by science, not stigma - The Future of Drugs

Psychedelic medicine, smart molecules, and new possibilities - Conclusion

A smarter, kinder future for drug policy

1. Introduction – What Is a Drug?

Drugs are everywhere in modern life. We take them to treat illnesses, to feel better, to focus, to sleep, or to escape. Some are handed out at the pharmacy with a prescription; others are bought on the street or legalized for weekend use. Some are praised as lifesaving miracles. Others are feared, banned, or even cause wars. But what exactly is a drug?

In simple terms, a drug is any substance that changes how your body or mind works. That includes everything from painkillers and antibiotics to coffee, cannabis, and LSD. Some drugs help us heal. Others change how we feel, think, or see the world. And sometimes, the same drug can do all of these things—depending on how it’s used.

This article explores the science behind drugs—what they are, how they work, and why they affect us so deeply. We’ll take a journey from ancient herbal remedies to modern pharmaceuticals, from the chemistry of molecules to the mysteries of the mind. Along the way, we’ll look at both legal and illegal substances, discuss addiction and healing, and ask some tough but necessary questions: Why are some drugs accepted while others are criminalized? Does the science support those decisions? And what could a smarter, fairer drug policy look like?

Drugs are powerful. They can save lives, ruin them, or expand our understanding of what it means to be human. Understanding drugs means understanding ourselves—our brains, our needs, and our choices.

2. What Happens When You Take a Drug – A Simple Look at Chemistry and the Body

Every time you take a drug—whether it’s a cup of coffee, a sleeping pill, or something stronger—you’re starting a chemical conversation with your body. That conversation begins with a molecule and ends with a feeling, an effect, or a change in how your body functions.

So how does it work?

When you swallow, smoke, inject, or absorb a drug, its active ingredients enter your bloodstream and travel through your body. Some drugs head straight to the brain, crossing what’s called the blood-brain barrier, which protects your brain from most harmful substances. Once there, they latch onto special sites in your cells called receptors—kind of like keys fitting into locks.

Different drugs target different systems. Some increase your heart rate or blood pressure. Others calm you down, relieve pain, or make you feel euphoric. Many affect the neurotransmitters in your brain—chemical messengers like dopamine, serotonin, and GABA that help control your mood, focus, and behavior.

For example:

- Caffeine blocks a molecule that makes you feel sleepy, giving you a temporary jolt of alertness.

- Opioids mimic the body’s natural painkillers, giving relief but also a strong sense of pleasure—one reason they’re addictive.

- Antidepressants like SSRIs increase the amount of serotonin available in the brain, which may help regulate mood over time.

- Cannabis interacts with the body’s built-in endocannabinoid system, affecting everything from appetite to perception.

The effects of a drug depend on its dose, how fast it’s absorbed, your biology, and even your mood and environment. The same drug can feel totally different for different people—or for the same person at different times.

Scientists use two important terms to understand how drugs behave:

- Pharmacodynamics is what the drug does to your body (the effects).

- Pharmacokinetics is what your body does to the drug (how it’s absorbed, broken down, and removed).

Some drugs act quickly and disappear fast (like a puff of nicotine), while others build up slowly or stay in your system for hours or days (like antidepressants or certain painkillers).

Whether the goal is to relieve pain, fight infection, or change consciousness, all drugs rely on chemistry—and that chemistry shapes both healing and harm.

3. A Short History of Drugs – From Plants and Potions to Modern Medicine

Long before scientists wore lab coats or companies made pills in factories, people were experimenting with nature to treat pain, sickness, and spiritual experiences. Some of the first “drugs” came from plants, roots, mushrooms, and minerals. Ancient healers and shamans learned what worked by trial, error, and tradition—passing knowledge from one generation to the next.

- In ancient China, herbs like ginseng and ephedra were used for energy and breathing problems.

- In India, the system of Ayurveda included treatments made from over 1,000 plant-based compounds.

- In the Americas, Indigenous peoples used peyote and tobacco for ceremony and healing.

- Ancient Egyptians recorded over 800 drugs in papyrus scrolls—including honey, opium, and moldy bread (which contains penicillin-like bacteria).

- In Greek and Roman medicine, physicians like Hippocrates and Galen prescribed herbal remedies, many of which are still studied today.

As time passed, alchemists in the Middle Ages began experimenting with distillation, extraction, and fermentation—paving the way for modern chemistry. But it wasn’t until the 1800s that scientists began to isolate the active ingredients in these remedies.

- Morphine was first extracted from opium in 1805—it was stronger and more predictable than raw opium.

- Quinine from tree bark became the first real treatment for malaria.

- Cocaine was isolated from coca leaves and briefly used as a painkiller and even in soda.

- In 1928, penicillin was discovered by accident—launching the antibiotic era and saving millions of lives.

By the 20th century, chemistry and medicine had joined forces to create the modern pharmaceutical industry. New drugs were developed to treat everything from infections to heart disease, depression, and cancer. Hospitals, pharmacies, and research labs became the new centers of drug discovery.

But not all drugs stayed in the realm of healing. In the 1960s and 70s, psychedelics like LSD and psilocybin exploded into mainstream culture, promising mind-expansion and rebellion—but also triggering legal crackdowns. Meanwhile, cannabis—used for centuries in Asia and the Middle East—was banned in many Western countries, despite evidence of its medical uses.

Today, the story continues. Scientists are exploring psychedelics again for mental health treatment. Cannabis is being legalized in more places. And new frontiers in gene-targeted therapy, AI-designed drugs, and personalized medicine are transforming what drugs can do—and who they’re for.

From ancient roots to digital labs, the science of drugs is really the story of how humans try to heal, feel better, and understand themselves.

4. Medicine and Healing – How Prescription Drugs Help (and Sometimes Harm)

When you get sick and visit a doctor, chances are you’ll leave with a prescription. These drugs—antibiotics, blood pressure pills, antidepressants, insulin, and hundreds more—are part of modern medicine’s greatest toolkit. They’ve helped people live longer, recover faster, and manage conditions that were once fatal or untreatable.

Prescription drugs are carefully tested and regulated. They go through years of research, clinical trials, and government approval. Each one is designed to treat a specific problem in the body—by killing bacteria, reducing inflammation, stabilizing mood, or replacing something your body is missing.

Here are a few common examples:

- Antibiotics kill harmful bacteria, saving lives from infections that used to be deadly. But they don’t work on viruses—and overuse can lead to resistance.

- Antidepressants help balance brain chemicals like serotonin, which can affect mood, sleep, and anxiety. They don’t work instantly, and not for everyone, but they can be life-changing for many.

- Blood pressure medications help prevent heart attacks and strokes by relaxing blood vessels or slowing the heartbeat.

- Insulin allows people with diabetes to manage their blood sugar—a discovery that turned a fatal disease into a manageable one.

These drugs are powerful tools. But like all tools, they come with risks. Almost every drug has side effects—unintended changes in the body that can range from mild (like drowsiness or dry mouth) to serious (like liver damage or addiction). That’s why doctors weigh the benefits vs. risks when prescribing, and why patients must follow instructions carefully.

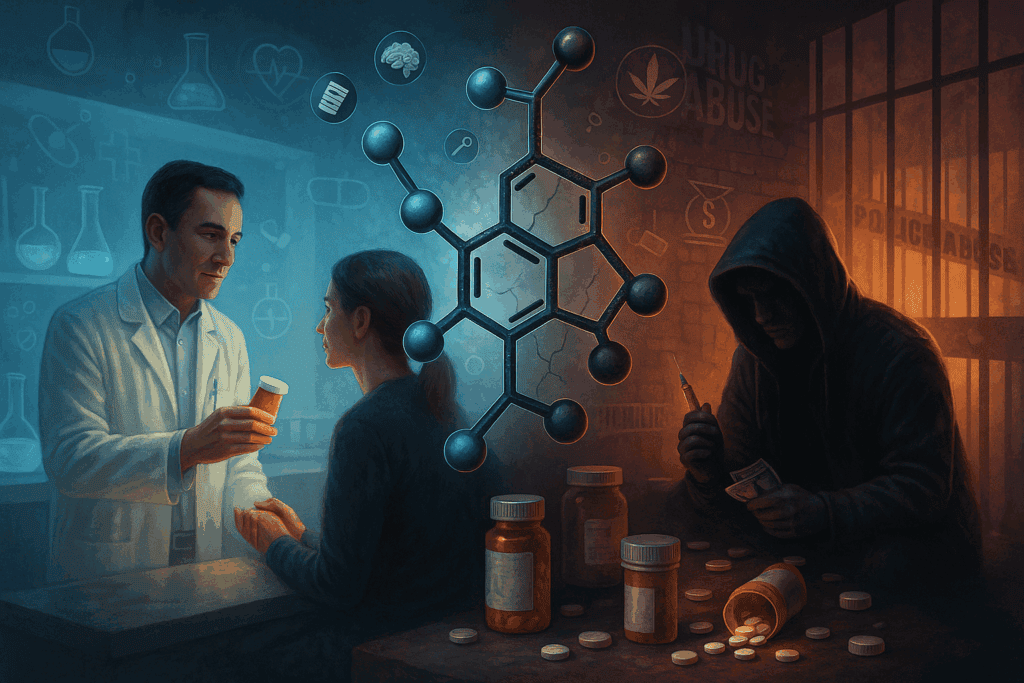

There are also bigger concerns that have come to light in recent decades:

Some drugs are overprescribed.

Doctors sometimes face pressure from patients, insurance companies, or pharmaceutical marketing. This has led to overuse of certain drugs:

- Opioids like oxycodone and hydrocodone were heavily prescribed for pain relief—even for minor injuries—fueling a massive addiction crisis.

- Antibiotics are often given for viral infections like colds and flu, even though they have no effect, contributing to dangerous antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

- Benzodiazepines such as Xanax and Valium are meant for short-term use, but are frequently prescribed long-term for anxiety or sleep, increasing the risk of dependence.

Some drugs are too expensive.

Despite their medical importance, certain life-saving drugs are priced far beyond what many people can afford:

- Insulin prices in the U.S. have risen so high that some diabetics are forced to ration doses—sometimes with tragic results.

- Hepatitis C treatments like Sovaldi can cure the disease, but cost tens of thousands of dollars per patient.

- Cancer therapies such as immunotherapy drugs (e.g., Keytruda) may offer breakthroughs in treatment, but can cost over $100,000 a year—out of reach for many.

Other drugs are frequently misused.

Even prescription drugs can be taken in ways that weren’t intended—recreationally, in high doses, or without a prescription:

- Adderall and Ritalin, used to treat ADHD, are often misused by students or professionals trying to stay focused or boost performance.

- Cough syrups with codeine are sometimes mixed into sugary drinks to create a recreational high—popularized as “lean” or “purple drank.”

- Gabapentin, prescribed for nerve pain or seizures, is increasingly misused for its sedative effects, especially in combination with opioids.

Despite these problems, prescription drugs remain one of the greatest tools in modern healthcare. They are often life-saving. But they also serve as a reminder that drugs are never just chemical compounds—they are wrapped up in systems of economics, ethics, access, and regulation.

Next, we turn to a different category: the drugs people use not to treat illness, but to change how they feel.

5. Feeling Different – Why People Use Recreational Drugs

Not all drugs are taken to treat disease. Some are used to relax, have fun, feel good, or escape pain—whether that pain is physical, emotional, or existential. These are known as recreational drugs, and they’ve been part of human life for thousands of years.

People use recreational drugs for many reasons:

- To socialize or feel more confident

- To explore altered states of consciousness

- To experience pleasure, relaxation, or euphoria

- To cope with stress, trauma, or boredom

- To rebel, experiment, or seek meaning

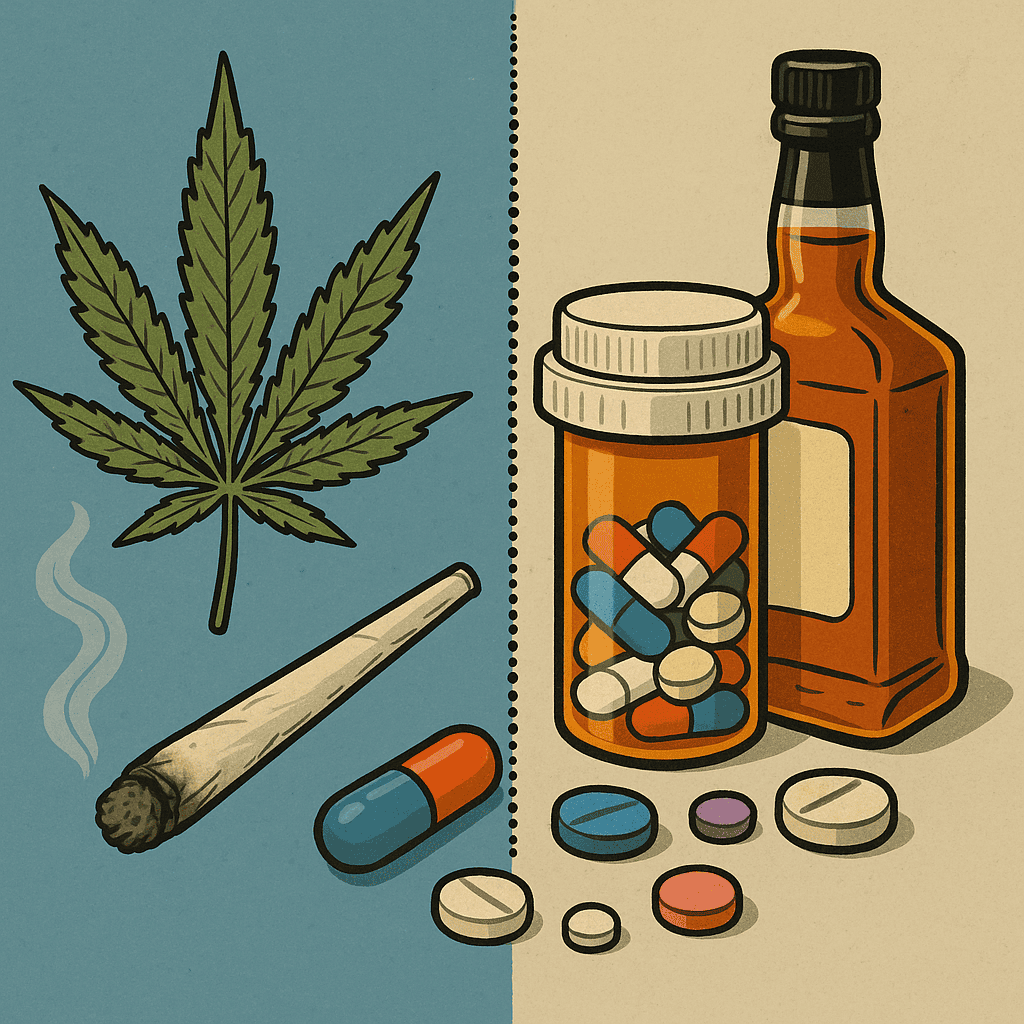

Some of these substances are legal and widely used—like alcohol, nicotine, and caffeine. Others—like cannabis, LSD, or cocaine—are illegal in many places, even though they may have similar or milder effects than legal ones. The line between accepted and forbidden often has more to do with history, politics, or culture than with science.

Let’s look at some common types of recreational drugs and what they do:

Stimulants (e.g., cocaine, amphetamines, MDMA)

These drugs speed up activity in the brain and body. They can increase energy, alertness, and mood. MDMA (also called ecstasy or molly) often brings feelings of empathy and closeness to others. But stimulants can also cause anxiety, heart problems, and burnout. Over time, they can be addictive and damage the brain’s natural reward system.

Depressants (e.g., alcohol, benzodiazepines)

Depressants slow down the nervous system. They can help people feel calm, relaxed, or sleepy—but at higher doses, they can affect judgment, memory, and coordination. Alcohol is legal and widely accepted, yet it causes more health problems and deaths worldwide than most illegal drugs.

Cannabis (marijuana)

Cannabis affects the body’s endocannabinoid system, influencing mood, appetite, memory, and perception. Its main active compound, THC, can make people feel relaxed, euphoric, or more aware of sights and sounds. CBD, another compound, is non-psychoactive and being studied for medical uses. Cannabis is now legal in many places, though it remains federally restricted in others.

Psychedelics (e.g., LSD, psilocybin mushrooms, DMT)

These drugs alter perception, thought, and sense of self. Some people report life-changing insights or spiritual experiences. Others may have confusing or frightening trips. New research suggests psychedelics may help treat depression, PTSD, and addiction—but they are still illegal in most parts of the world.

Dissociatives (e.g., ketamine, nitrous oxide, PCP)

These substances can create a feeling of detachment from the body or reality. Ketamine, in low doses, is now being used in some clinics to treat severe depression. But higher doses may lead to memory problems, risky behavior, or psychological harm.

It’s important to remember that how a drug is used matters just as much as what the drug is. Set, setting, dose, and intention all play a role in the experience and its outcome.

Drugs that alter consciousness can open doors—or create chaos. They can inspire, soothe, or destroy. The same substance might be healing in one context and harmful in another.

In the next section, we’ll explore the deeper risks of drug use—especially the biology and psychology of addiction.

5. Feeling Different – Why People Use Recreational Drugs

Not all drugs are taken to treat disease. Some are used to relax, have fun, feel good, or escape pain—whether that pain is physical, emotional, or existential. These are known as recreational drugs, and they’ve been part of human life for thousands of years.

People use recreational drugs for many reasons:

- To socialize or feel more confident

- To explore altered states of consciousness

- To experience pleasure, relaxation, or euphoria

- To cope with stress, trauma, or boredom

- To rebel, experiment, or seek meaning

Some of these substances are legal and widely used—like alcohol, nicotine, and caffeine. Others—like cannabis, LSD, or cocaine—are illegal in many places, even though they may have similar or milder effects than legal ones. The line between accepted and forbidden often has more to do with history, politics, or culture than with science.

Let’s look at some common types of recreational drugs and what they do:

Stimulants (e.g., cocaine, amphetamines, MDMA)

These drugs speed up activity in the brain and body. They can increase energy, alertness, and mood. MDMA (also called ecstasy or molly) often brings feelings of empathy and closeness to others. But stimulants can also cause anxiety, heart problems, and burnout. Over time, they can be addictive and damage the brain’s natural reward system.

Depressants (e.g., alcohol, benzodiazepines)

Depressants slow down the nervous system. They can help people feel calm, relaxed, or sleepy—but at higher doses, they can affect judgment, memory, and coordination. Alcohol is legal and widely accepted, yet it causes more health problems and deaths worldwide than most illegal drugs.

Cannabis (marijuana)

Cannabis affects the body’s endocannabinoid system, influencing mood, appetite, memory, and perception. Its main active compound, THC, can make people feel relaxed, euphoric, or more aware of sights and sounds. CBD, another compound, is non-psychoactive and being studied for medical uses. Cannabis is now legal in many places, though it remains federally restricted in others.

Psychedelics (e.g., LSD, psilocybin mushrooms, DMT)

These drugs alter perception, thought, and sense of self. Some people report life-changing insights or spiritual experiences. Others may have confusing or frightening trips. New research suggests psychedelics may help treat depression, PTSD, and addiction—but they are still illegal in most parts of the world.

Dissociatives (e.g., ketamine, nitrous oxide, PCP)

These substances can create a feeling of detachment from the body or reality. Ketamine, in low doses, is now being used in some clinics to treat severe depression. But higher doses may lead to memory problems, risky behavior, or psychological harm.

It’s important to remember that how a drug is used matters just as much as what the drug is. Set, setting, dose, and intention all play a role in the experience and its outcome.

Drugs that alter consciousness can open doors—or create chaos. They can inspire, soothe, or destroy. The same substance might be healing in one context and harmful in another.

In the next section, we’ll explore the deeper risks of drug use—especially the biology and psychology of addiction.

7. Rules and Reality – Who Decides What’s Legal?

If you look at how the law treats drugs, you might think there’s a clear, scientific line between “safe medicine” and “dangerous narcotic.” But the truth is a lot messier.

Some of the most addictive and harmful drugs—like alcohol and nicotine—are perfectly legal and widely advertised. Meanwhile, other substances that may be less harmful—or even medically useful—are still banned in many countries. Cannabis, for example, has been illegal for decades in many places, despite evidence that it’s less harmful than alcohol and can help with pain, nausea, and anxiety.

So who makes these rules? And do they reflect science—or something else?

How drugs get classified

In most countries, drugs are divided into legal “medications” and illegal “controlled substances.” In the U.S., the government uses a system called the Controlled Substances Act, which places drugs into five “schedules”:

- Schedule I includes drugs with “no accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.” This list includes heroin, LSD, psilocybin, and cannabis.

- Schedule II drugs have medical uses but are considered highly addictive—like morphine, Adderall, or cocaine.

- Schedule III–V drugs are considered to have lower abuse potential.

But there’s a big problem: these schedules don’t always match the latest science. For example:

- Cannabis is still listed as Schedule I, even though it’s legal for medical or recreational use in many U.S. states, and research supports its therapeutic value.

- Psilocybin, found in “magic mushrooms,” is also Schedule I—even as studies show it may help with depression and PTSD.

- Alcohol and tobacco aren’t even on the schedule—despite being among the most harmful drugs in terms of addiction, disease, and death.

Why the laws don’t always match the facts

The legal status of a drug often reflects:

- Politics: Drug policy has been shaped by historical fears, election agendas, and culture wars.

- Racism and classism: Many drug bans were originally tied to discrimination—targeting specific immigrant or minority groups.

- Economics: Legal drugs can be heavily taxed and regulated, while some illegal drugs compete with powerful industries.

- Stigma and fear: Media coverage and social attitudes can exaggerate the dangers of certain substances, even when science says otherwise.

The result? A legal system that often punishes people for drug use rather than helping them, while allowing other, equally harmful substances to be sold at the corner store.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

In the next section, we’ll explore what a science-based drug classification might look like—and how we can build smarter, fairer laws that reflect evidence, not fear.

8. A New Framework – Classifying Drugs by Science, Not Stigma

Imagine if we could design drug laws from scratch—not based on fear, history, or politics, but on actual scientific evidence. What would that look like?

Researchers, doctors, and public health experts have been asking that question for years. And many agree: our current drug classifications don’t match the real risks and benefits of different substances. In fact, some of the most harmful drugs are legal, while some of the safest remain banned.

So how could we build a better system?

Classifying drugs by harm

In 2010, British scientist David Nutt and his team published a groundbreaking study ranking 20 common drugs based on their actual harm—both to the user and to society. Their findings were eye-opening:

- Alcohol ranked as the most harmful overall—more than heroin or crack cocaine—mainly due to accidents, addiction, violence, and health issues.

- Heroin, crack, and methamphetamine followed in personal risk and health damage.

- Tobacco causes major harm through cancer and heart disease, yet remains legal and widely available.

- Cannabis, LSD, and psilocybin mushrooms ranked among the least harmful—especially in terms of social impact and addiction potential.

This study didn’t claim any drug was perfectly safe. But it showed clearly: the legal status of a drug often has little to do with the actual science.

What would a science-based system do differently?

- Base laws on risk, not cultural history or political narratives.

- Treat addiction as a health issue, not a criminal one.

- Support harm reduction, like clean needle programs, safe consumption sites, and access to treatment.

- Encourage research, especially into promising but stigmatized substances like psychedelics and cannabis.

- Protect youth and public health with honest education, not fear-based campaigns.

Some countries are already experimenting with smarter approaches:

- Portugal decriminalized all drugs in 2001. Instead of punishment, users are offered treatment and support. Drug deaths and HIV infections dropped dramatically.

- Canada, Switzerland, and others offer supervised sites for safer drug use, reducing overdoses.

- Oregon became the first U.S. state to decriminalize personal possession of small amounts of all drugs, focusing on health over punishment.

We still need regulations. Drugs can be dangerous—especially when misused, mixed, or used without support. But laws should be honest, compassionate, and grounded in facts.

Science doesn’t promise perfect answers. But it can help us build a better, more humane approach to drugs—one that saves lives, reduces harm, and respects both public health and personal freedom.

Next, we’ll look ahead to where this science is going: psychedelic therapies, AI-designed drugs, and the future of medicine.

9. The Future of Drugs – Psychedelic Medicine, Smart Molecules, and New Possibilities

The science of drugs is moving fast. What once seemed like fringe ideas—like using psychedelics to treat depression, or designing drugs with artificial intelligence—is now serious research. We’re entering a new era where medicine may not just treat disease, but reshape how we experience our minds and bodies.

Psychedelic therapy: Healing through altered states

After decades of stigma, psychedelics like LSD, psilocybin (magic mushrooms), and MDMA are being studied again for mental health treatment—and the results are promising.

- Psilocybin has shown potential in treating major depression, anxiety, and even end-of-life distress in terminal patients.

- MDMA-assisted therapy is in late-stage trials for PTSD, where it helps people process trauma with reduced fear.

- Ketamine, originally an anesthetic, is now used in some clinics to rapidly relieve suicidal depression.

These therapies don’t just mask symptoms. They seem to help the brain reset—breaking stuck patterns, enhancing emotional insight, and opening a window for deep healing. In safe, controlled settings with professional guidance, they could offer hope for people who haven’t responded to other treatments.

AI and smart drug design

Artificial intelligence is beginning to change how we create drugs. Instead of testing millions of random compounds in a lab, researchers can now use AI to:

- Predict how a molecule will interact with the body

- Optimize drugs for fewer side effects

- Design completely new compounds, faster and more precisely

This could speed up drug development, lower costs, and lead to personalized medicines tailored to your genes, gut bacteria, or brain chemistry.

Other breakthroughs on the horizon:

- Microdosing (taking very small, non-psychoactive doses of psychedelics) is being explored for boosting mood, focus, and creativity—though results are still mixed.

- Digital drugs: Some scientists are studying how sound, light, or electromagnetic pulses can affect brain chemistry without any substance at all.

- Gene-targeted treatments: Future drugs may correct genetic errors or tune your immune system with incredible precision.

- Nanodrugs: Microscopic machines that deliver medicine exactly where it’s needed, like tiny guided missiles for disease.

We are no longer just treating illness. We’re beginning to enhance cognition, reprogram emotions, and even reimagine consciousness.

Of course, these advances bring big questions: Who gets access? Who controls them? How do we make sure powerful new tools are used wisely, and not just sold for profit or escape?

That brings us to the final question.

What kind of drug policy—and what kind of society—do we want to build?

10. Conclusion – A Smarter, Kinder Future for Drug Policy

Drugs are powerful. They can heal the sick, transform the mind, or cause deep harm. They’re made of molecules, but their impact reaches far beyond chemistry—touching on law, culture, economics, mental health, and personal freedom.

For too long, the way we’ve approached drugs has been shaped more by fear and politics than by science or compassion. We’ve punished people instead of helping them. We’ve criminalized substances based on outdated ideas. And we’ve overlooked the potential of some drugs to bring real healing—especially for those suffering from trauma, depression, or chronic pain.

But things are changing.

Science is helping us see drugs more clearly—not as good or evil, but as tools. Tools that can be used wisely or recklessly. Tools that deserve respect, not stigma. And like all tools, they should be guided by evidence, ethics, and care.

What would a smarter, kinder drug policy look like?

- It would be based on real risk, not political history.

- It would treat addiction as a health issue, not a crime.

- It would fund research, not fear.

- It would give people accurate education, not scare tactics.

- And it would aim for healing and harm reduction, not punishment and profit.

We’re living in a time when the science of drugs is evolving faster than ever. With that comes a choice. We can cling to the old stories—or we can write a new one.

A story where drug policy is guided by truth.

Where treatment is available without shame.

Where the goal isn’t just control, but care.

And where every person—no matter what they use, or why—has a chance to be seen, supported, and safe.

Bibliography

Carhart-Harris, R.L., Erritzoe, D., Williams, T. et al., 2012. Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(6), pp.2138–2143.

Graham, J., 2023. Scientists Finally Found the Psychedelic Source of LSD. Popular Mechanics. [online] 26 Sep. Available at: https://www.popularmechanics.com/science/a64966021/scientists-finally-found-the-psychedelic-source-of-lsd/ [Accessed 6 Jun. 2025].

Graham, J., 2023. Altered Consciousness: What Happens to Your Brain on Psychedelics. Popular Mechanics. [online] 19 Jul. Available at: https://www.popularmechanics.com/science/a64636206/altered-consciousness-psychedelic/ [Accessed 6 Jun. 2025].

Gorelick, D.A. and Montoya, I.D., 2012. The science of drug abuse and addiction: The basics. National Institute on Drug Abuse. [online] Available at: https://nida.nih.gov/publications/media-guide/science-drug-use-addiction-basics [Accessed 6 Jun. 2025].

Guttmacher Institute, 2019. Medication Costs and Access to Drugs in the United States. [online] Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/ [Accessed 6 Jun. 2025].

Hart, C.L., 2021. Drug Use for Grown-Ups: Chasing Liberty in the Land of Fear. New York: Penguin Press.

Nutt, D., King, L.A., and Phillips, L.D., 2010. Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis. The Lancet, 376(9752), pp.1558–1565.

Pollan, M., 2018. How to Change Your Mind: The New Science of Psychedelics. New York: Penguin Press.

Portugal Ministry of Health, 2021. Drug Decriminalization in Portugal: Lessons for Creating Fair and Effective Drug Policies. [online] Available at: https://www.health.gov.pt/ [Accessed 6 Jun. 2025].

World Health Organization (WHO), 2019. Global status report on alcohol and health. Geneva: World Health Organization.