Table of Contents

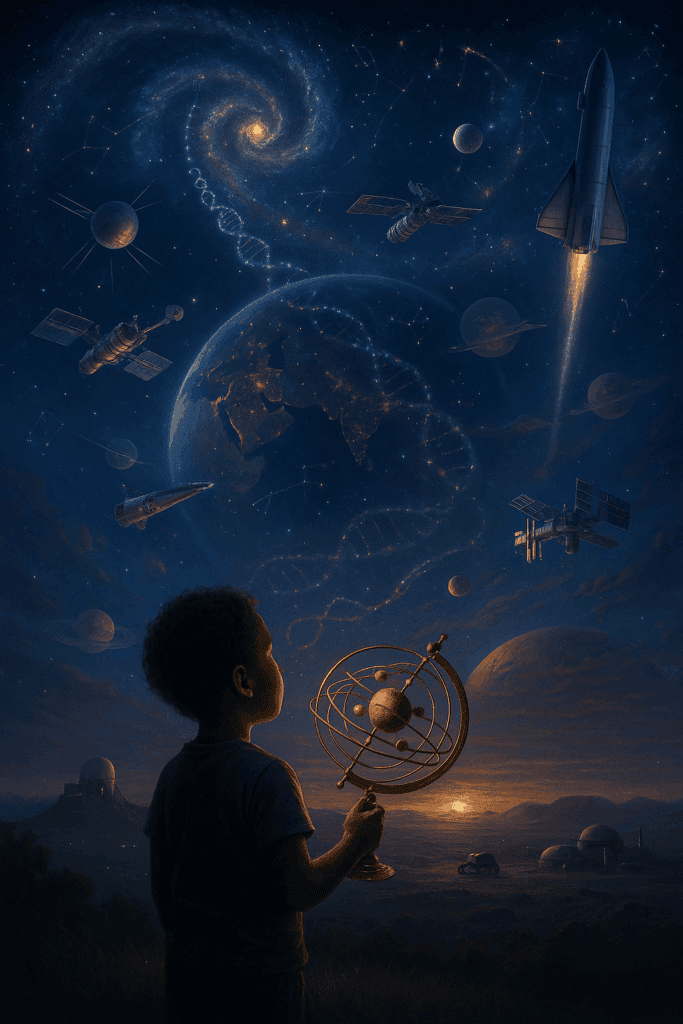

I. Introduction – Humanity’s Cosmic Curiosity

- The age-old yearning to understand the skies

- From myths to missions: why we reach for the stars

II. Ancient Skies: Astrology and Early Astronomy

- Astrology and early sky-watching cultures (Babylon, Egypt, China, Mesoamerica)

- The transition to observational astronomy (Greece, India, Islam)

III. The Age of Telescopes and Observatories

- Galileo, Kepler, Newton, and the scientific revolution

- Development of optical telescopes and early observatories

- The rise of astrophysics and photographic sky surveys

IV. Rocket Science and the Birth of Space Programs

- Tsiolkovsky, Goddard, and the pioneers of rocketry

WWII and the V-2 rocket

Cold War competition: USSR vs. USA space race

V. The Era of Human and Robotic Space Missions

- Sputnik and Explorer: the satellite revolution

- Yuri Gagarin and the first human in space

- The Apollo Moon missions

Space probes and robotic explorers (Voyager, Curiosity, James Webb)

VI. Satellites, Space Shuttles, and the Space Station

- How satellites changed Earth (weather, GPS, surveillance)

- NASA’s Space Shuttle program

The International Space Station (ISS): science in low orbit

VII. Governments and Global Space Agencies

- NASA, Roscosmos, ESA, CNSA, ISRO, and others

- Military and surveillance interests

- Diplomacy, international cooperation, and competition

VIII. The Modern Era: Private Companies and New Technologies

- SpaceX, Blue Origin, Virgin Galactic: commercial spaceflight

- Reusable rockets, cubesats, ion propulsion, 3D printing in orbit

AI, robotics, and remote sensing in space science

IX. The Future of Space Exploration

- Missions to Mars, Europa, and beyond

- Moon bases, asteroid mining, space elevators

- SETI, exoplanets, and the search for life

- Ethical, environmental, and philosophical challenges

X. Conclusion – A Shared Journey into the Cosmos

- The meaning of exploration in the 21st century

- Unity, curiosity, and the evolving human story in space

I. Introduction – Humanity’s Cosmic Curiosity

From the moment our ancestors first looked skyward, the heavens have stirred something profound within the human spirit. Long before the written word or the wheel, humans charted the movements of stars, noticed patterns in the night sky, and crafted myths to explain celestial phenomena.

These early efforts to make sense of the cosmos mark the origins of a journey that continues to this day—a journey driven by awe, curiosity, and an enduring desire to understand our place in the universe.

Over millennia, this primal curiosity evolved into systematic inquiry. Astrology gave way to astronomy, myth to mathematics, and speculative philosophy to empirical science. The telescope revolutionized our view of the cosmos, transforming points of light into worlds. The rocket turned dreams of flight into the reality of space travel. Space programs became theaters of competition, cooperation, and inspiration.

Today, space exploration stands at a new threshold. With the rise of private space companies, miniaturized technologies, and new ambitions for Mars and beyond, we are once again expanding the frontier. As humanity reaches outward—through satellites, space stations, telescopes, and robotic scouts—we also reflect inward, recognizing that our fate is bound to the stars not only by curiosity, but by necessity.

This article explores the history, technologies, and philosophical stakes of space exploration—from ancient skywatchers to modern space stations, and from Cold War rivalries to the cooperative dreams of interstellar travel. It is a story of science, politics, wonder, and survival. It is a story of us.

II. Ancient Skies – Astrology and Early Astronomy

Long before telescopes or scientific method, ancient cultures observed the heavens with a sense of reverence, fear, and fascination. The sky was a cosmic calendar, a canvas of divine messages, and a map for earthly survival. In this pre-scientific age, astrology and astronomy were one—blending myth, mathematics, and observation into systems that governed life and kingship.

Skywatchers and Star-Temples

Across Mesopotamia, Egypt, Mesoamerica, India, and China, priest-astronomers tracked the stars to guide agriculture, predict floods, and validate political authority. In Babylon, ziggurats served as celestial observatories; from them, scribes recorded planetary motions and eclipses with astonishing precision. The Babylonians developed a zodiac system and ephemerides—precursors to modern star charts.

The ancient Egyptians aligned temples and pyramids to key stars like Sirius, whose heliacal rising heralded the Nile’s inundation. In Mesoamerica, the Maya charted Venus cycles with mathematical rigor, linking them to rituals and warfare. The Chinese recorded supernovae, comets, and solar phenomena with systematic diligence, maintaining celestial records for over two millennia.

The Rise of Celestial Order

Indian astronomers, influenced by both Vedic traditions and mathematical insight, produced advanced models of planetary motion. The Surya Siddhanta (c. 4th–5th century CE) calculated solar eclipses and planetary orbits with remarkable accuracy. In ancient Greece, thinkers like Thales, Pythagoras, and Eudoxus began moving from mythic cosmology to natural philosophy. Aristotle and Ptolemy would later formalize a geocentric universe—placing Earth at the unmoving center, orbited by crystalline spheres.

In the Hellenistic world and Islamic Golden Age, observational astronomy blossomed. The great observatories of Baghdad, Samarkand, and Córdoba preserved and refined Greco-Roman astronomical knowledge, while contributing original discoveries. Al-Battani, Al-Tusi, and Ibn al-Shatir corrected earlier planetary models and developed trigonometric methods still used today.

Astrology’s Persistent Legacy

Though today separated from scientific astronomy, astrology played a vital historical role. It motivated recordkeeping, institutional support, and theoretical developments. Court astrologers were often among the best-funded scientists of their day. Predictions about eclipses, omens, and planetary alignments were central to imperial decisions.

Even as scientific astronomy emerged, astrology remained influential—guiding explorers, physicians, and philosophers well into the Renaissance. The divide between astrology and astronomy did not sharpen until the rise of empiricism and testable hypotheses in early modern science.

III. The Age of Telescopes and Observatories

The invention of the telescope in the early 17th century marked a profound turning point in humanity’s relationship with the cosmos. What had once been fixed and mysterious points of light suddenly became landscapes, spheres, and systems. Observational astronomy—fueled by mathematics, optics, and daring new hypotheses—ushered in a scientific revolution that would ultimately displace Earth from the center of the universe.

Galileo and the Telescope’s Birth

Though early optical devices had been developed in the Islamic world and Renaissance Europe, it was Galileo Galilei in 1609 who first systematically turned a telescope to the heavens. What he saw shattered established dogmas. Mountains and craters on the Moon, sunspots on the Sun, Jupiter’s four largest moons orbiting their planet, and the phases of Venus all contradicted Aristotelian cosmology and supported Copernicus’ heliocentric model.

The telescope revealed that the heavens were not perfect and unchanging, as once believed. It invited a new question: If Earth was not the center, what else might lie beyond?

Kepler, Newton, and the Mathematical Sky

In parallel, Johannes Kepler refined planetary motion into three laws using Tycho Brahe’s meticulous data. He showed that planets travel in ellipses—not perfect circles—and that their speeds vary depending on their distance from the Sun.

Isaac Newton, building on Kepler and Galileo, united celestial and terrestrial physics under a single set of laws. His Principia Mathematica (1687) demonstrated that gravity governed both falling apples and planetary orbits. The sky was now a field for mathematical prediction.

This shift—toward universal physical laws—transformed astronomy into a predictive science and cemented its break from mystical astrology.

Observatories as Instruments of Empire and Enlightenment

With telescopes growing in size and precision, dedicated observatories emerged across Europe, Asia, and the Islamic world. Royal patrons and academies funded them as symbols of prestige and instruments of navigation and empire. By the 18th and 19th centuries, observatories in Greenwich, Paris, St. Petersburg, Jaipur, and Beijing were central to both scientific progress and political power.

Celestial mechanics aided the conquest of oceans and empires. Accurate stellar charts and ephemerides were vital for longitude calculation, timekeeping, and global exploration.

The Rise of Astrophysics

In the 19th century, advances in spectroscopy and photography revolutionized the observational toolkit. Astronomers began to analyze the composition, temperature, and motion of stars—launching the era of astrophysics.

Scientists like William Herschel, Annie Jump Cannon, and Henrietta Leavitt contributed to star classification, galactic mapping, and the measurement of cosmic distances. Observatories became research laboratories, expanding from visible light into radio, infrared, ultraviolet, and eventually X-ray astronomy.

The age of the telescope transformed humanity from passive sky-gazers into active cosmic investigators. It laid the intellectual and technological foundations for the next great leap: leaving Earth itself.

IV. Rocket Science and the Birth of Space Programs

The idea of leaving Earth and traveling to the stars is ancient—but the technology to do so is surprisingly recent. Rocketry, once the stuff of legends and fireworks, became a precise and powerful science in the 20th century. It was born from bold thinkers, hardened in war, and transformed into a tool for exploration.

From Fire Arrows to Mathematical Dreams

Primitive rockets were used as early as the 13th century in China and India—simple gunpowder-propelled projectiles for warfare and spectacle. But it was not until the late 19th and early 20th centuries that visionary scientists began to imagine rockets as vehicles for space travel.

- Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, a Russian schoolteacher and mathematician, first formulated the rocket equation, proving that space travel was possible in theory. He advocated liquid fuel and multi-stage designs.

- Robert H. Goddard, an American physicist, built and launched the first liquid-fueled rocket in 1926, achieving stable flight and laying the groundwork for practical rocketry.

- Hermann Oberth in Germany popularized spaceflight through visionary publications, inspiring a generation of scientists and engineers.

Though these pioneers were often dismissed or ignored in their time, their theoretical work set the stage for the real-world applications that would soon follow.

War, Technology, and the V-2 Rocket

During World War II, rocketry became a weapon of war. Under Wernher von Braun, Nazi Germany developed the V-2 rocket—the world’s first long-range guided ballistic missile. It could strike targets hundreds of miles away and reached the edge of space in its arc.

While a weapon of destruction, the V-2 was also the first human-made object to reach space. After the war, both the United States and the Soviet Union raced to recruit German rocket scientists and capture the technology. This transfer of knowledge marked the beginning of the Cold War space race.

The Cold War and the Space Race

The 1950s and 60s saw a dramatic escalation of rocket development, not just for military dominance but for technological and ideological prestige. The United States and Soviet Union invested heavily in space programs as part of their broader Cold War rivalry.

- In 1957, the USSR shocked the world by launching Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite, into Earth orbit.

- In 1958, the U.S. responded by founding NASA (the National Aeronautics and Space Administration).

- In 1961, Yuri Gagarin became the first human in space aboard Vostok 1, orbiting the Earth once before returning safely.

These early milestones transformed rocketry into the foundation of a global space age. No longer merely a scientific curiosity or a weapon of war, rockets became symbols of humanity’s aspiration—and capacity—to reach beyond Earth.

Toward the Moon and Beyond

President John F. Kennedy’s bold 1961 commitment to “land a man on the Moon and return him safely to the Earth” by the end of the decade galvanized the American space program. The Saturn V, the most powerful rocket ever built, carried Apollo 11 and astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins to the Moon in 1969.

This achievement was not only a technical marvel—it was a political, philosophical, and human milestone. For the first time, humanity had reached another world.

The birth of space programs was not just the triumph of engineering—it was a transformation of human identity. From the battlefield to the launchpad, rocketry had taken us from war-torn ground to the threshold of the cosmos.

V. The Era of Human and Robotic Space Missions

With rockets proven capable of reaching orbit and even the Moon, the space age entered a new phase: the systematic exploration of space by humans and machines. Each mission expanded the frontier of the possible, transforming our understanding of Earth, the Solar System, and our place in it.

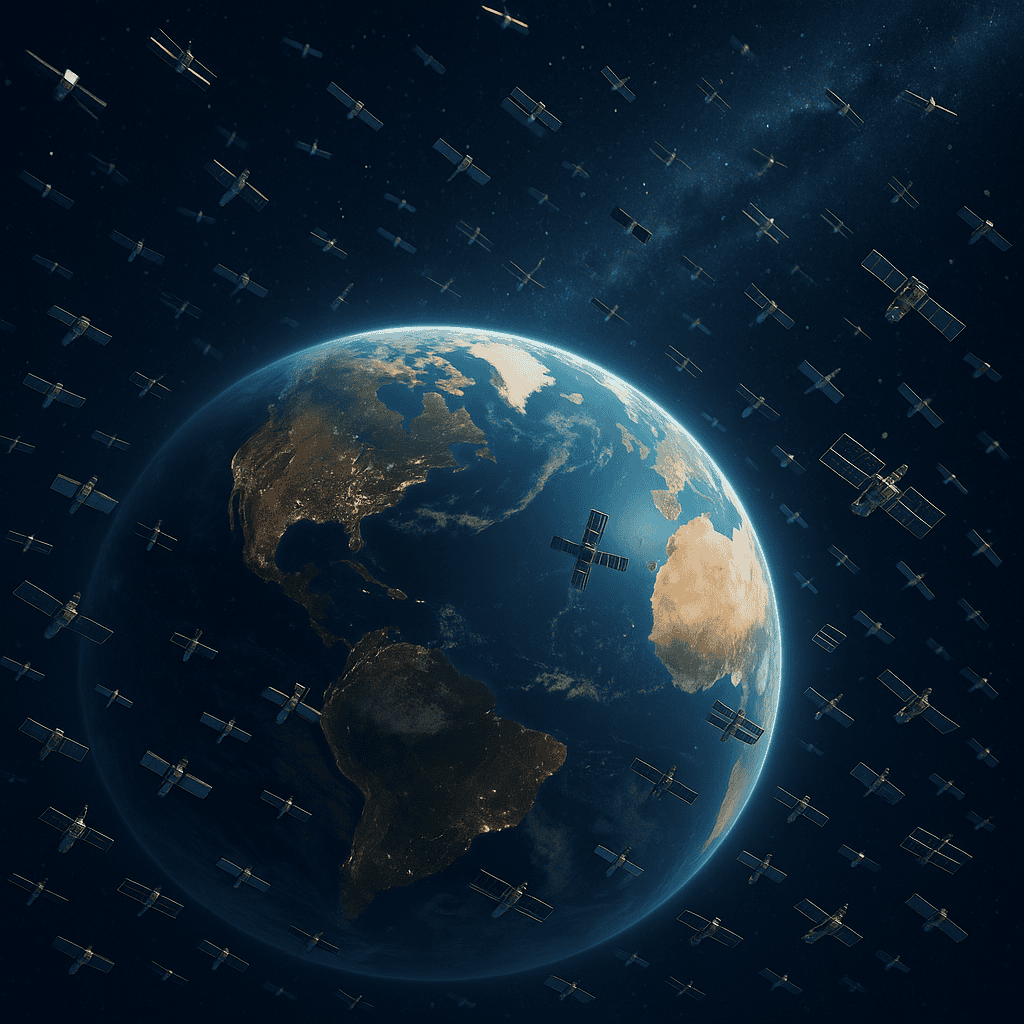

Satellites and the View from Above

The launch of Sputnik 1 in 1957 inaugurated the satellite era. Though small and short-lived, it marked the beginning of space as a platform for continuous observation, communication, and surveillance.

The following decades witnessed a surge of satellite deployments:

- Weather satellites like TIROS revolutionized meteorology.

- Communications satellites (Telstar, Intelsat) reshaped global media.

- Navigation satellites laid the foundation for today’s GPS systems.

- Earth observation satellites enabled detailed mapping, resource monitoring, and climate science.

From orbit, Earth became not just a planet but a living, measurable system—fragile, finite, and shared.

Human Spaceflight: First Steps and Giant Leaps

In 1961, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human to orbit Earth. Weeks later, American astronaut Alan Shepard made a suborbital flight. The rivalry between the USSR and USA would soon become a race to the Moon.

- The U.S. Gemini and Apollo programs tested space rendezvous, EVA (spacewalks), and deep-space navigation.

- In 1969, Apollo 11 landed on the Moon. Neil Armstrong’s “giant leap for mankind” was broadcast to over 500 million people.

- Between 1969 and 1972, six Apollo missions landed humans on the Moon, conducting experiments, gathering samples, and deploying instruments.

These missions revealed a desolate yet stunning landscape—and offered a cosmic perspective that profoundly moved the public. The “Earthrise” photo from Apollo 8 became an icon of the environmental movement, reminding humanity of its unity and vulnerability.

The Age of Robotic Explorers

Even as humans explored the Moon, robotic spacecraft were beginning their own epic journeys:

- The Voyager 1 and 2 probes launched in 1977 to explore the outer planets—and are now traveling through interstellar space.

- The Pioneer and Mariner missions mapped Venus, Mars, and Mercury.

- The Viking landers became the first to operate on the Martian surface (1976).

- The Cassini–Huygens mission orbited Saturn and landed a probe on its moon Titan.

- The New Horizons mission flew by Pluto in 2015, revealing an icy world of unexpected complexity.

These machines, bearing the minds and dreams of their creators, revealed an astonishing diversity of planetary systems, moons, rings, atmospheres, and geological activity. They turned blurry points of light into alien worlds.

Space Science Today: Telescopes and Rovers

Space is not just a destination—it is a laboratory. Modern science missions use space to study both the universe and life on Earth:

- The Hubble Space Telescope (launched in 1990) has captured some of the most detailed images of galaxies, nebulae, and cosmic evolution ever seen.

- The James Webb Space Telescope (2021) peers even deeper into time, toward the first stars and galaxies.

- Mars rovers like Spirit, Opportunity, Curiosity, and Perseverance have studied the Martian surface, searching for signs of past water and habitability.

- Orbiters around Jupiter, Venus, and the Sun continue to transmit torrents of data.

Some of these missions last years beyond their projected lifespan, becoming enduring symbols of scientific perseverance and ingenuity.

Together, human and robotic missions have transformed outer space from an abstract mystery into a vast, dynamic frontier. With each probe and astronaut, the cosmos has become more intimate—and more astonishing.

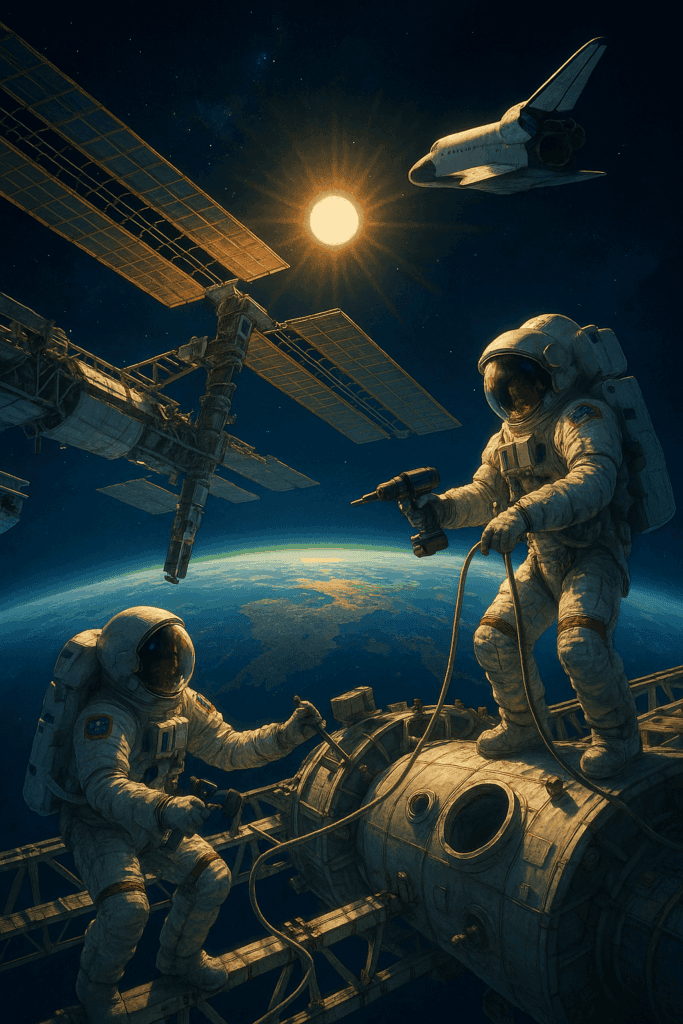

VI. Satellites, Space Shuttles, and the Space Station

As space exploration matured, focus shifted from singular missions to building a sustainable human and technological presence in orbit. Satellites became ubiquitous, shuttles revolutionized launch and recovery, and the dream of a permanent outpost in space became a reality. Earth’s near orbit—once the edge of the unknown—was now an active zone of innovation, industry, and international collaboration.

Satellites: The Infrastructure of the Modern World

Today, thousands of satellites orbit Earth, performing tasks essential to modern civilization:

- Communication satellites support global broadcasting, internet, and mobile networks.

- Weather satellites track storms, climate patterns, and seasonal shifts.

- Remote sensing satellites monitor deforestation, urban growth, and ocean temperatures.

- Military and reconnaissance satellites provide critical strategic data and global surveillance.

Satellites have made the Earth observable and knowable in ways never before possible. From agriculture to geopolitics, they have reshaped human activity across every domain.

The Space Shuttle: Reusability and Risk

In the 1980s, NASA introduced the Space Shuttle, a partially reusable spacecraft designed to make space access more routine. With five orbiters—Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, Atlantis, and Endeavour—the Shuttle conducted 135 missions between 1981 and 2011.

Key achievements included:

- Launching and repairing the Hubble Space Telescope

- Constructing modules for the International Space Station (ISS)

- Deploying scientific instruments and satellites

- Facilitating cooperation between U.S. and international astronauts

However, the program was costly and fraught with tragedy. The Challenger disaster in 1986 and the Columbia disaster in 2003—both due to preventable failures—claimed the lives of 14 astronauts and revealed the dangers of reusing complex hardware in an unforgiving environment.

Despite its shortcomings, the Shuttle era redefined the possibilities of crewed spaceflight and deepened global investment in orbital infrastructure.

The International Space Station: A Lab Above the World

The International Space Station, assembled between 1998 and the 2010s, represents one of the most ambitious scientific collaborations in human history. Built and operated by NASA, Roscosmos, ESA (Europe), JAXA (Japan), and CSA (Canada), the ISS orbits Earth every 90 minutes, hosting rotating crews of scientists, engineers, and astronauts.

The ISS serves as:

- A zero-gravity laboratory for biology, materials science, physics, and medicine

- A testbed for long-duration human spaceflight (critical for future Mars missions)

- A symbol of post-Cold War cooperation in space

Its modules house cutting-edge experiments, from cancer research to 3D printing in orbit. The station has also served as an educational and diplomatic platform, with astronauts from dozens of nations contributing.

The Legacy and Transition

As the ISS ages and the Shuttle fleet has retired, space agencies and private companies now seek new vehicles and stations:

- NASA’s Orion and SpaceX’s Dragon capsules now ferry astronauts to orbit.

- Private efforts are exploring commercial space stations, like those envisioned by Axiom Space.

- China has launched its own modular space station, Tiangong, signaling a new era of multipolar space infrastructure.

Low Earth orbit is no longer a novelty—it is becoming a strategic and economic zone. The challenges of sustaining human life, performing science, and ensuring safety in orbit continue to drive innovation.

From satellites to stations, humanity has carved out a second home in the sky—a realm once reserved for myth, now managed with precision. These platforms orbit not just Earth, but the center of our shared aspirations.

VII. Governments and Global Space Agencies

While individual missions capture the imagination, it is government-led space agencies that have shaped the infrastructure, strategy, and long-term vision of space exploration. These institutions coordinate vast networks of scientists, engineers, funding, and policy. They are the architects of the space age—and increasingly, its stewards and competitors.

NASA: America’s Spacefaring Vanguard

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was founded in 1958, amid Cold War anxieties and a national desire to surpass Soviet space achievements. Since then, NASA has led many of the most iconic missions in human history:

- The Apollo Moon landings

- The Space Shuttle and Hubble Space Telescope

- Robotic missions like Voyager, Mars rovers, and the James Webb Space Telescope

NASA is a civilian agency, but its close relationship with the U.S. military and federal budget reflects how space is both a domain of science and national power. Its focus today includes Moon-to-Mars missions, Earth science, and fostering commercial partnerships.

Roscosmos and the Legacy of the Soviet Space Program

Russia’s Roscosmos agency, successor to the Soviet space program, is historically renowned for:

- Launching Sputnik, the first satellite

- Sending Yuri Gagarin, the first human in space

- Developing long-duration human spaceflight via the Mir space station

Though diminished in scope since the Soviet collapse, Roscosmos remains a crucial space player—particularly in human spaceflight and launch capabilities. Russian Soyuz rockets have served as the workhorse of global crew transport for decades.

ESA, JAXA, and Global Collaboration

The European Space Agency (ESA) unites over 20 European nations, pooling resources for space science, Earth observation, planetary exploration, and human spaceflight. ESA has launched Mars orbiters, contributed major components to the ISS, and collaborates closely with NASA and Roscosmos.

Japan’s JAXA has pioneered missions like:

- Hayabusa (asteroid sample returns)

- Contributions to the ISS

- Lunar and Martian exploration efforts

Smaller agencies—from the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) to Brazil’s INPE and South Korea’s KARI—also contribute to specialized missions, satellite launches, and international partnerships.

India and China: Rising Space Powers

India’s ISRO (Indian Space Research Organisation) has emerged as a cost-effective, ambitious actor in space. It has launched:

- Chandrayaan missions to the Moon

- Mangalyaan to Mars (first Asian Mars orbiter)

- Dozens of satellites for Earth observation and navigation

China’s CNSA (China National Space Administration) is now a major space superpower. Highlights include:

- The Chang’e Moon missions and lunar samples

- Tianwen-1, a Mars orbiter, lander, and rover

- The Tiangong Space Station, built independently of the ISS

China’s program blends scientific objectives with strategic autonomy, and it is rapidly closing the technological gap with the West.

Military, Intelligence, and Dual-Use Ambitions

Space is not only a domain of science—it is also a domain of military significance. Governments invest in:

- Spy satellites and geospatial intelligence (GEOINT)

- Missile defense systems and early warning networks

- Cybersecurity and anti-satellite (ASAT) capabilities

The creation of the U.S. Space Force in 2019 reflects the increasing militarization and securitization of space. Similar programs exist in China, Russia, and India, raising concerns about the potential for space conflict.

International Agreements and Governance Challenges

Global cooperation in space is guided by frameworks like:

- The Outer Space Treaty (1967), which prohibits national sovereignty claims in space

- The Artemis Accords (2020s), a U.S.-led initiative promoting peaceful exploration

Yet many questions remain unresolved:

- Who owns resources mined from asteroids or the Moon?

- How do we prevent the weaponization of space?

- How can space debris and overcrowding be responsibly managed?

Governments remain the primary custodians of space infrastructure, law, and vision. Yet as new players rise and ambitions grow, the need for shared governance and peaceful cooperation has never been more urgent.

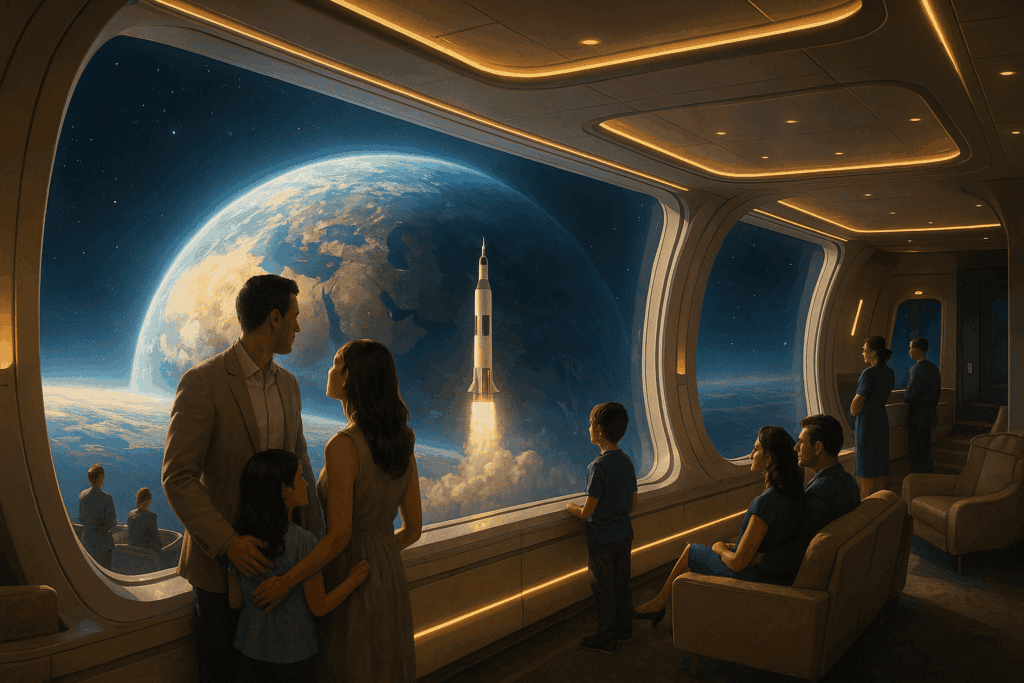

VIII. The Modern Era – Private Companies and New Technologies

The 21st century has witnessed a dramatic shift in the landscape of space exploration. What was once the exclusive domain of state-run programs is now increasingly driven by private companies, entrepreneurs, and startups. This shift—sometimes called the “New Space” movement—has spurred a renaissance in innovation, competition, and ambition, reshaping the future of humanity’s presence in space.

From Contractors to Creators: The Rise of SpaceX and Beyond

In the early days, private companies built components for government missions. Today, they build and launch entire spacecraft and satellites, often more efficiently and affordably than traditional agencies.

- SpaceX, founded by Elon Musk in 2002, has revolutionized access to space with its Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets. Its innovations include:

- Reusable rocket stages, reducing launch costs dramatically

- Regular cargo and crew missions to the International Space Station

- The development of Starship, designed for lunar and interplanetary travel

- Reusable rocket stages, reducing launch costs dramatically

- Blue Origin, founded by Jeff Bezos, is developing New Shepard for suborbital tourism and New Glenn for orbital payloads. Its long-term vision includes millions living and working in space.

- Virgin Galactic and Virgin Orbit (Virgin Group founded by Richard Branson) focus on space tourism and small satellite launches respectively, exploring air-launched systems and civilian access to space.

These companies have helped reignite public interest, bring down launch costs, and push the boundaries of space infrastructure.

The Rise of Commercial Satellites and Megaconstellations

Thousands of commercial satellites are now in orbit, serving purposes from Earth imaging to global broadband.

- Starlink (SpaceX) and Project Kuiper (Amazon) aim to deploy tens of thousands of satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO) to provide global high-speed internet.

- Companies like Planet Labs and Maxar offer near-real-time Earth imaging for agriculture, disaster response, and security.

While these advances offer connectivity and insight, they also raise concerns about space debris, radio interference, and orbital crowding.

New Technologies Transforming Space

The private sector and new government programs have introduced a suite of cutting-edge technologies:

- Reusable rockets and landing boosters dramatically reduce costs.

- CubeSats and smallsats allow universities, companies, and even high schools to launch scientific experiments affordably.

- Ion propulsion enables longer, more efficient interplanetary travel.

- 3D printing in orbit allows for repairs and manufacturing without returning to Earth.

- Artificial intelligence powers autonomous navigation, fault detection, and deep space communication.

- Robotic arms and drones conduct in-orbit servicing of satellites.

These tools are making space more accessible, modular, and sustainable.

Moon, Mars, and Beyond: Commercial Deep Space Ambitions

Private companies are not content with orbit. Many now set their sights on the Moon, Mars, and asteroid mining:

- SpaceX’s Starship is intended to transport cargo and humans to the Moon and Mars, with NASA selecting it as a human landing system for Artemis missions.

- Asteroid mining startups (e.g., Planetary Resources, now defunct, and newer ventures) dream of harvesting water, metals, and rare elements from near-Earth objects.

- Lunar lander companies are working with NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) to deliver instruments to the Moon’s surface.

Private space stations are also being developed, with firms like Axiom Space planning commercial habitats in low Earth orbit to succeed the ISS.

The Democratization and Commercialization of Space

While governments still fund foundational science, private enterprise is rapidly commercializing access, ownership, and opportunity in space:

- Universities can launch CubeSats.

- Startups can provide real-time Earth data or asteroid surveys.

- Tourists can pay to reach suborbital space.

However, this democratization raises ethical and regulatory concerns:

- Who regulates private activity in space?

- Who owns the Moon’s resources?

- How can equity be ensured in the face of commercial monopolies?

The modern era of space is defined by speed, innovation, and decentralization. Private actors are pushing technology and infrastructure forward—but they also force us to confront the political, environmental, and philosophical implications of a future where space is no longer a commons, but a marketplace.

IX. The Future of Space Exploration

The frontier of space is no longer a distant vision—it is rapidly becoming a present reality. As humanity moves beyond low Earth orbit and toward permanent extraterrestrial presence, the future of space exploration is taking shape around ambitious goals, transformative technologies, and urgent ethical questions.

Returning to the Moon—and Staying

NASA’s Artemis Program, with international and commercial partners, aims to return humans to the Moon by the mid-2020s—this time with permanence in mind. Key objectives include:

- Establishing a lunar base camp for extended missions

- Building the Lunar Gateway, a space station orbiting the Moon

- Testing systems for eventual Mars travel

Other nations—especially China, with its planned Changk’e lunar base—are developing parallel projects. The Moon may soon host scientific laboratories, mining operations, and even tourist visits.

Mars Missions and Interplanetary Ambition

Mars is the next great leap. With its thin atmosphere, ancient riverbeds, and potential for past life, it remains both scientifically tantalizing and symbolically powerful. NASA, ESA, CNSA, and SpaceX each envision:

- Sample return missions (already underway with Perseverance and planned follow-ups)

- Human missions in the 2030s or beyond

- Testing closed-loop life support, autonomous robotics, and in-situ resource utilization (ISRU)

Mars colonization raises profound questions: What are the biological risks? Who governs a Martian settlement? Should we terraform—and if so, for whom?

Asteroids, Exoplanets, and the Search for Life

Beyond planetary goals, space science is increasingly focused on life detection and cosmic origins:

- Missions to Europa, Enceladus, and Titan aim to explore subsurface oceans that may harbor life.

- James Webb Space Telescope and upcoming observatories seek biosignatures in exoplanet atmospheres.

- SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) and related initiatives continue to scan for radio or optical signals from advanced civilizations.

Asteroids, once feared as harbingers of extinction, are now viewed as potential mines and fuel depots. They offer resources like water, platinum-group metals, and construction materials—if we can reach and process them sustainably.

Space Elevators, Fusion, and the Technological Horizon

Some of tomorrow’s concepts sound like science fiction but are under serious study:

- Space elevators could revolutionize orbital access if materials like carbon nanotubes become viable.

- Nuclear propulsion (including fusion) could drastically cut interplanetary travel time.

- Artificial gravity, radiation shielding, and biological augmentation may help humans adapt to life beyond Earth.

Meanwhile, the development of AI astronauts, quantum communications, and interstellar probes (e.g., Breakthrough Starshot) expands our reach into the truly unknown.

Governance, Ethics, and the Cosmic Commons

As our technological capacity grows, so too do the stakes:

- Will space remain a peaceful and cooperative domain, or become an arena of conflict and colonization?

- Who gets to make decisions on behalf of Earth or humanity?

- How can we preserve celestial bodies from irreversible contamination or commercialization?

Some propose space as a universal commons, guided by a planetary ethos. Others see it as a new economic and strategic frontier. The next decades will test whether humanity can mature politically and ethically to meet its newfound cosmic agency.

The future of space exploration will be a measure not only of our scientific ingenuity, but of our collective wisdom. Will we reach for the stars as caretakers, or as conquerors? The answer will shape not just the heavens—but the fate of life on Earth.

X. Conclusion – A Shared Journey into the Cosmos

From the ancient astrologers who etched star maps into stone to the robotic probes sailing past the edge of the solar system, the human journey into space has been nothing short of extraordinary. It is a story not only of science and technology, but of vision, courage, cooperation—and longing.

We have mapped constellations and orbits, stood on the Moon, peered into the hearts of galaxies, and listened for signals across the silence of light-years. We have launched machines that carry our curiosity, our questions, and our names into the dark. In doing so, we have come to see ourselves with new clarity: not as rulers of a vast cosmos, but as fragile travelers on a small blue planet, suspended in a sea of stars.

Today, space is a laboratory, a frontier, a theater of power, and a source of unity. It reveals our deepest paradoxes: our brilliance and our blindness, our competitive instinct and our collaborative potential. It invites both technological marvel and moral reflection.

In the years ahead, space exploration will define who we are as a species. Will we extract, exploit, and militarize the heavens? Or will we cultivate them as stewards and scientists, artists and dreamers, building a cosmic legacy grounded in humility and hope?

To journey into space is not to escape Earth, but to understand it more deeply—to recognize that every launch, every image from a distant moon, every whisper of cosmic radiation, returns us not only knowledge, but a renewed responsibility.

We are stardust become conscious. Our voyage into space is a continuation of evolution—of life seeking to know itself.

This is not the story of rockets or empires. It is the story of humanity as one species, sharing one sky, charting one future. And though we still stand at the very beginning of this journey, the stars are no longer beyond our reach.

They are part of our story now.