Table of Contents

Introduction

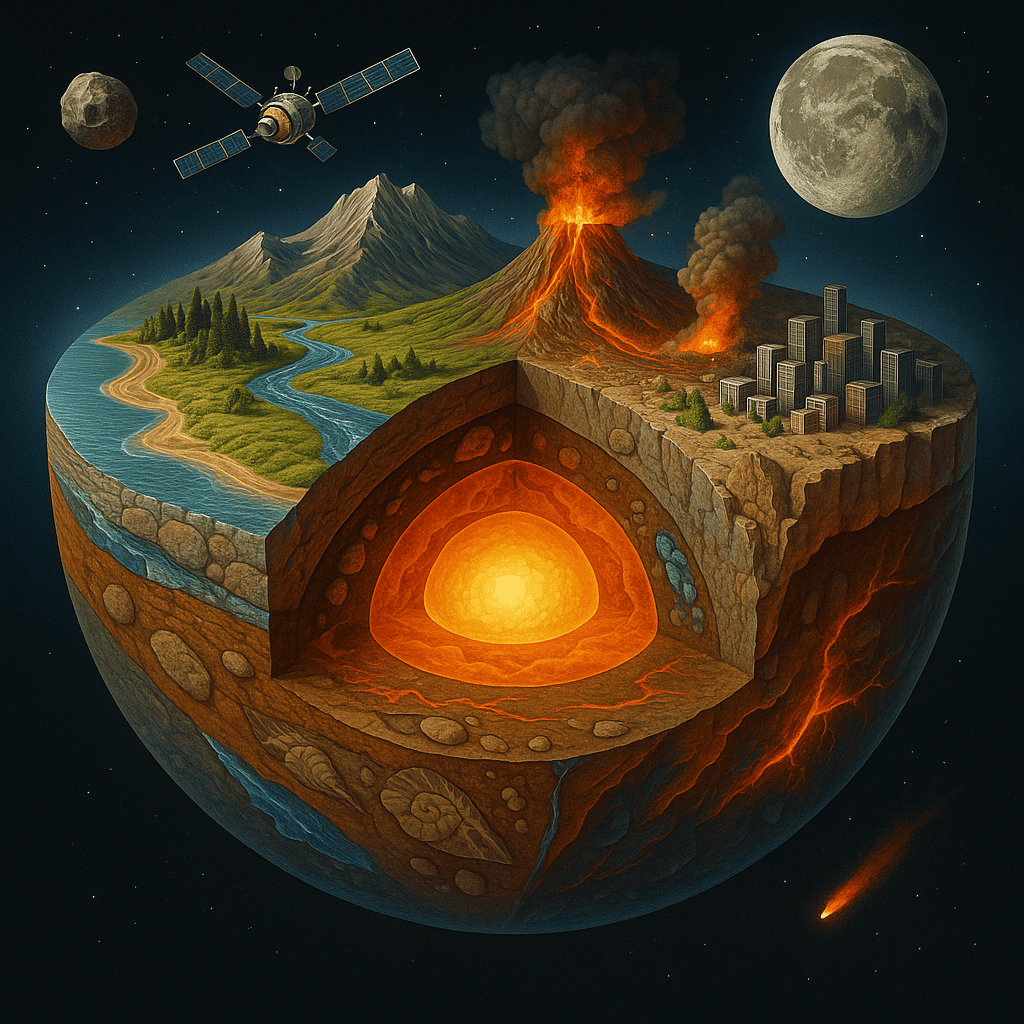

I. The Origins of the Earth

- The Hadean Earth: Magma, Bombardment, and Atmosphere

- The Onset of Plate Tectonics

- The Geochronological Record

- Field Connections

- From Origins to Life

II. Earth’s Layers and Lithosphere

- Structure of the Earth

- The Rock Cycle: Earth’s Dynamic Skin

- Plate Tectonics and Lithospheric Motion

- Scientific Fields Involved

- Why It Matters

III. Volcanoes, Magma, and Earthquakes

- Magma: The Molten Engine of Change

- Volcanoes: Creators and Destroyers

- Earthquakes: Shaking the Foundations

- Volcanoes and Earthquakes: Tectonic Expressions

- Scientific Fields Involved

- Living With Geologic Hazards

IV. Surface Processes and Landform Evolution

- Weathering: Breaking Down the Old

- Erosion and Transport: Moving the Earth

- Deposition and Landform Creation

- Landform Systems

- Why It Matters

V. Earth’s History and the Record of Life

- The Geologic Time Scale

- Fossils: Clues to the Living Past

- Key Events in Earth’s Biological History

- The Role of Geobiology

- Scientific Fields Involved

- Why It Matters

VI. Earth Resources and the Global Economy

- Fossil Fuels: Ancient Sunlight

- Metals and Industrial Minerals

- Gems and Precious Metals

- Water and Soil: The Unsung Resources

- Global Impact and Geopolitical Dimensions

- Scientific Fields Involved

- Ethics and Management: An Integrated Humanist View

VII. The Politics of the Earth

- Strategic Resources and Global Tensions

- Environmental Justice and Extraction

- Infrastructure, Development, and Risk

- Climate Change and the Geological Lens

- Toward a New Geological Diplomacy

- Scientific Fields Involved

- Ethical Governance and Planetary Stewardship

VIII. Geology Beyond Earth

- The Solar System as a Laboratory

- Comparative Planetology and Earth’s Uniqueness

- Astrobiology and the Search for Life

- Space Mining and the Future Economy

- Scientific Fields Involved

- Why It Matters

IX. Geology and the Future of Humanity

- The Age of the Anthropocene

- Geological Challenges of the 21st Century

- Education, Equity, and Global Science

- Integrated Humanism and Earth Stewardship

- Conclusion: Grounded in the Future

Introduction

Geology is the scientific study of the Earth—its structure, composition, processes, and history. It is one of the oldest sciences, born from humanity’s earliest attempts to make sense of earthquakes, volcanoes, mountains, rivers, and the origins of the land beneath our feet. Today, geology has grown into a deeply interdisciplinary field that connects chemistry, physics, biology, and environmental science to understand not only the planet we inhabit, but also how we can live responsibly upon it.

The scope of geology is vast. It explores the origins of Earth and other planetary bodies, the evolution of life, the dynamic forces that reshape landscapes, and the resources that fuel civilization. Geologists investigate both deep time—spanning billions of years—and the immediate future, helping us forecast natural disasters and manage Earth’s finite resources.

In the 21st century, geology has become more urgent than ever. Climate change, environmental degradation, energy transitions, and geopolitical conflicts over natural resources all depend on our understanding of geological processes. The science of geology is no longer just academic—it is essential to survival, sustainability, and peace.

This article presents a comprehensive journey through the many subfields of geology, beginning with the formation of the Earth and ending with a vision of planetary stewardship. Along the way, it will examine the scientific discoveries, technological tools, and philosophical perspectives that have shaped our understanding of Earth—and offer a framework for managing its resources from an Integrated Humanist perspective.

I. The Origins of the Earth

The story of geology begins not on Earth, but in the stars.

Approximately 4.6 billion years ago, a cloud of gas and dust—composed of elements formed in the hearts of ancient stars—collapsed under its own gravity. This event, likely triggered by the shockwave of a nearby supernova, gave rise to a spinning disk of material known as the solar nebula. At its center, the Sun ignited. Around it, planets, moons, and asteroids slowly accreted from remaining matter.

Earth formed through violent collisions and gradual accumulation of rocky bodies in this early solar system. Initially a molten sphere, Earth underwent a process known as planetary differentiation, where heavier elements like iron and nickel sank to form the core, while lighter silicates rose to form the mantle and crust. These layers became the geological framework of the planet.

The Hadean Earth: Magma, Bombardment, and Atmosphere

The first 500 million years of Earth’s existence—known as the Hadean Eon—were hellish. The young planet was bombarded by asteroids and comets, its surface a sea of molten rock. But these cataclysms were also generative: water delivered by icy bodies likely contributed to the formation of Earth’s early oceans, while volcanic activity helped build the atmosphere through the release of gases.

As the Earth cooled, the crust began to solidify, allowing the formation of the first continental fragments. Magma chambers crystallized into igneous rocks, and tectonic activity—driven by internal heat—slowly began to shape the surface.

The Onset of Plate Tectonics

One of Earth’s most unique and vital features is plate tectonics—the slow movement of massive plates of crust across the planet’s surface. Although the precise timeline is debated, evidence suggests that some form of tectonic activity began more than 3 billion years ago. Plate tectonics continually reshapes the Earth, recycling crust, forming mountain ranges, driving volcanic eruptions, and generating earthquakes. It is the engine behind Earth’s geological dynamism.

The Geochronological Record

The early history of the planet is studied through the science of geochronology, which uses isotopic dating methods—such as uranium-lead, potassium-argon, and radiocarbon techniques—to determine the ages of rocks and minerals. These methods provide a timeline for the evolution of Earth’s surface and interior.

For example, the oldest known minerals—zircon crystals found in Western Australia—have been dated to 4.4 billion years. These tiny time capsules suggest that a solid crust and liquid water may have existed on Earth far earlier than previously believed.

Field Connections

- Geochemistry investigates the elemental composition of early Earth materials and the processes that created the core, mantle, and crust.

- Geophysics uses seismic waves and magnetic fields to map Earth’s interior.

- Planetary Geology compares Earth’s development to that of other rocky bodies, helping identify which features make our planet unique.

- Geochronology provides the timeline for all subsequent geological and biological events.

From Origins to Life

The formation of Earth set the stage for everything that followed—including the emergence of life. In subsequent chapters, we will explore the crust’s evolving complexity, the role of volcanoes and water, and how the record of rocks became the storybook of Earth’s dynamic journey.

II. Earth’s Layers and Lithosphere

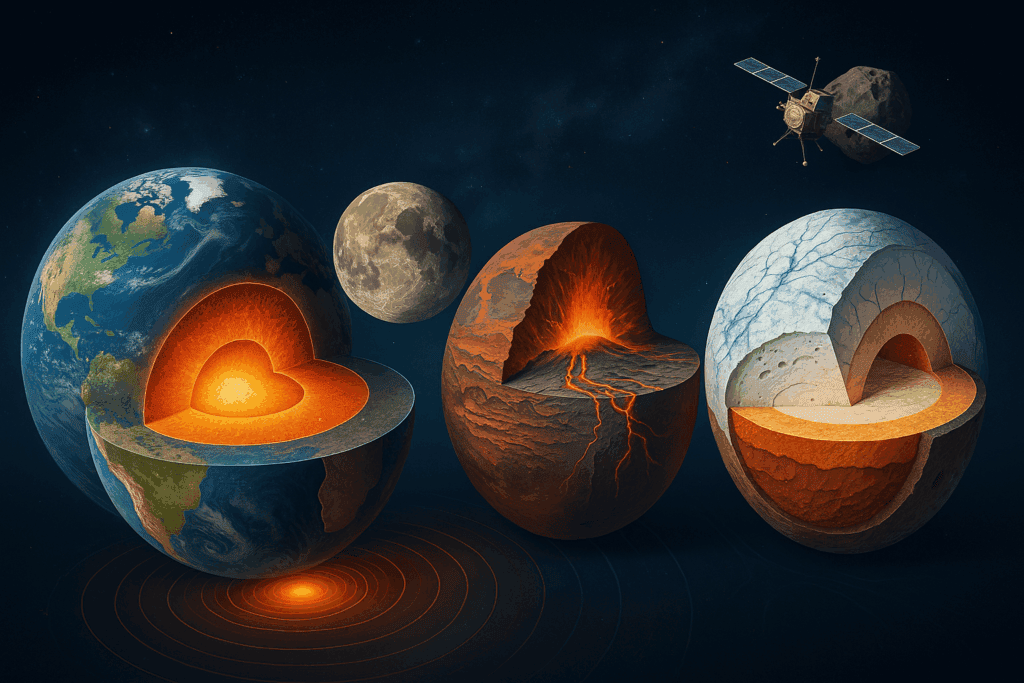

The Earth is not uniform. It is layered, dynamic, and ever-changing beneath our feet. Understanding these layers—both physically and chemically—is fundamental to geology.

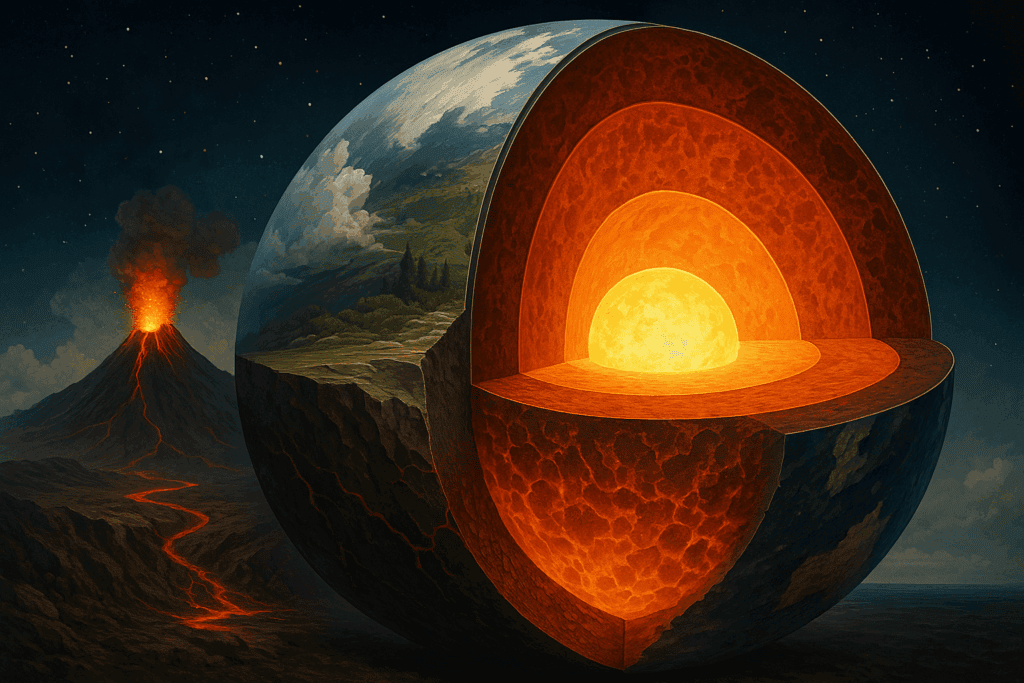

Structure of the Earth

Earth consists of four main internal layers:

- Inner Core – A dense, solid sphere composed primarily of iron and nickel, with temperatures reaching up to 5,700°C. Despite the heat, it remains solid due to immense pressure.

- Outer Core – A liquid layer also made of iron and nickel. Its convection currents generate Earth’s magnetic field.

- Mantle – A thick, mostly solid layer of silicate rock that flows slowly over geological timescales. It is the main source of magma and drives tectonic activity.

- Crust – The outermost, thinnest layer, varying in thickness from 5 km (oceanic crust) to 70 km (continental crust). It is composed of various types of rocks and minerals and is where all life and human activity takes place.

Together, the crust and the uppermost solid part of the mantle form the lithosphere—a rigid, brittle shell broken into tectonic plates that float atop the ductile asthenosphere, a weak zone in the upper mantle.

The Rock Cycle: Earth’s Dynamic Skin

The lithosphere is composed of three major rock types, which transform through a continuous rock cycle:

- Igneous Rocks – Formed from cooled magma or lava. Examples: basalt, granite.

- Sedimentary Rocks – Formed from the accumulation and compaction of mineral and organic particles. Examples: sandstone, limestone.

- Metamorphic Rocks – Formed from existing rocks altered by heat, pressure, or chemical processes. Examples: marble, schist.

This cycle connects all major surface and deep-earth processes: volcanic eruptions produce igneous rock, erosion and deposition form sedimentary rock, and heat and pressure at depth create metamorphic rock—all of which may melt again to restart the cycle.

Plate Tectonics and Lithospheric Motion

Tectonic plates move atop the mantle’s convection currents, driven by heat from the core. This movement causes:

- Divergent boundaries – where plates move apart (e.g., Mid-Atlantic Ridge)

- Convergent boundaries – where plates collide, often forming mountains or subduction zones (e.g., Himalayas, Andes)

- Transform boundaries – where plates slide past each other (e.g., San Andreas Fault)

These boundaries generate earthquakes, mountain ranges, ocean trenches, and volcanic arcs, making them central to Earth’s geological dynamism.

Scientific Fields Involved

- Lithology focuses on the composition, texture, and classification of rocks.

- Structural Geology investigates folds, faults, and other deformations of the crust caused by tectonic forces.

- Igneous Petrology examines the origin and crystallization of magma.

- Sedimentary Geology explores processes of sediment transport, layering, and fossil preservation.

- Metamorphic Petrology studies the transformation of rocks under heat and pressure, often deep within orogenic (mountain-building) zones.

- Geophysics models Earth’s inner structure through seismic waves and gravitational anomalies.

Why It Matters

The lithosphere is Earth’s stage—where continents drift, oceans open and close, and life evolves. Its materials provide the raw ingredients of civilization, from the bedrock beneath our cities to the ores in our smartphones. And its behavior shapes natural hazards: quakes, tsunamis, eruptions.

To understand the lithosphere is to understand the foundation of our world—and how to live safely and sustainably upon it.

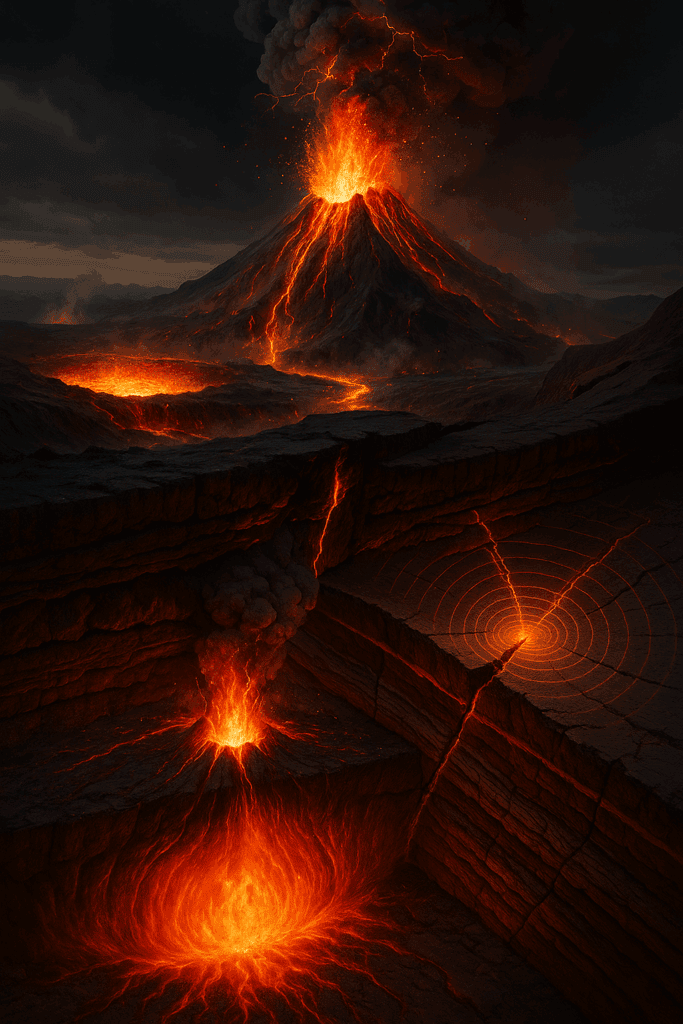

III. Volcanoes, Magma, and Earthquakes

The Earth is not static. Beneath the surface, forces build and release energy in dramatic expressions—volcanic eruptions and earthquakes. These powerful events are not merely destructive—they are essential to Earth’s dynamic renewal. They create land, enrich soils, and offer windows into the deep Earth.

Magma: The Molten Engine of Change

Magma is molten rock originating in the mantle or lower crust. It forms when pressure decreases, temperature increases, or volatiles like water lower the melting point of rocks. Depending on its composition, magma may be:

- Basaltic (low viscosity, common in oceanic settings)

- Andesitic (intermediate)

- Rhyolitic (high viscosity, common in explosive continental eruptions)

When magma reaches the surface, it becomes lava, forming new crust. As it cools and solidifies, it creates igneous rocks that record the story of Earth’s interior.

Volcanoes: Creators and Destroyers

Volcanoes are surface expressions of magma movement. They occur mainly along tectonic boundaries or over hotspots—plumes of rising mantle material. Major types of volcanoes include:

- Shield Volcanoes – Broad, gentle slopes (e.g., Mauna Loa, Hawaii)

- Stratovolcanoes – Steep, explosive (e.g., Mount Fuji, Japan)

- Cinder Cones – Small, steep, short-lived eruptions

- Calderas – Massive depressions formed after colossal eruptions (e.g., Yellowstone)

Volcanic activity contributes to atmospheric gases, builds landmasses, and recycles elements vital for life. But eruptions can also devastate regions through lava flows, pyroclastic surges, ash clouds, and climate-altering aerosols.

Earthquakes: Shaking the Foundations

An earthquake occurs when accumulated stress in Earth’s crust is suddenly released along a fault line. The energy radiates as seismic waves, felt as ground shaking. The epicenter is the surface point above the rupture, while the focus lies deeper underground.

Most earthquakes happen at tectonic boundaries:

- Convergent zones: Deep, powerful quakes

- Transform faults: Shallow, frequent quakes

- Divergent boundaries: Moderate, often undersea

Seismology, a branch of geophysics, measures and maps these events. By studying P-waves, S-waves, and surface waves, geologists can model Earth’s interior and better understand the nature of tectonic motion.

Volcanoes and Earthquakes: Tectonic Expressions

Both phenomena are rooted in plate tectonics:

- Subduction zones (e.g., Pacific Ring of Fire) produce explosive volcanoes and deep earthquakes

- Rift zones (e.g., East African Rift) produce basaltic flows and moderate seismic activity

- Transform boundaries (e.g., San Andreas Fault) host frequent, shallow quakes

These events remind us that Earth’s surface is in constant flux. While often feared, they are fundamental to Earth’s geological vitality.

Scientific Fields Involved

- Geophysics: Models magma movement and seismic wave propagation

- Igneous Petrology: Analyzes magma chemistry and crystallization

- Volcanology: Studies eruption dynamics, hazards, and historical activity

- Seismology: Maps fault systems, measures seismic energy, predicts risk zones

- Structural Geology: Interprets faulting, folding, and crustal deformation

Living With Geologic Hazards

Modern geology aims not only to understand, but also to protect. Volcano monitoring systems, seismic hazard maps, tsunami alerts, and earthquake-resistant architecture save lives.

These tools exemplify the power of science to transform awe into action—and to align human settlements with the deep rhythms of our living planet.

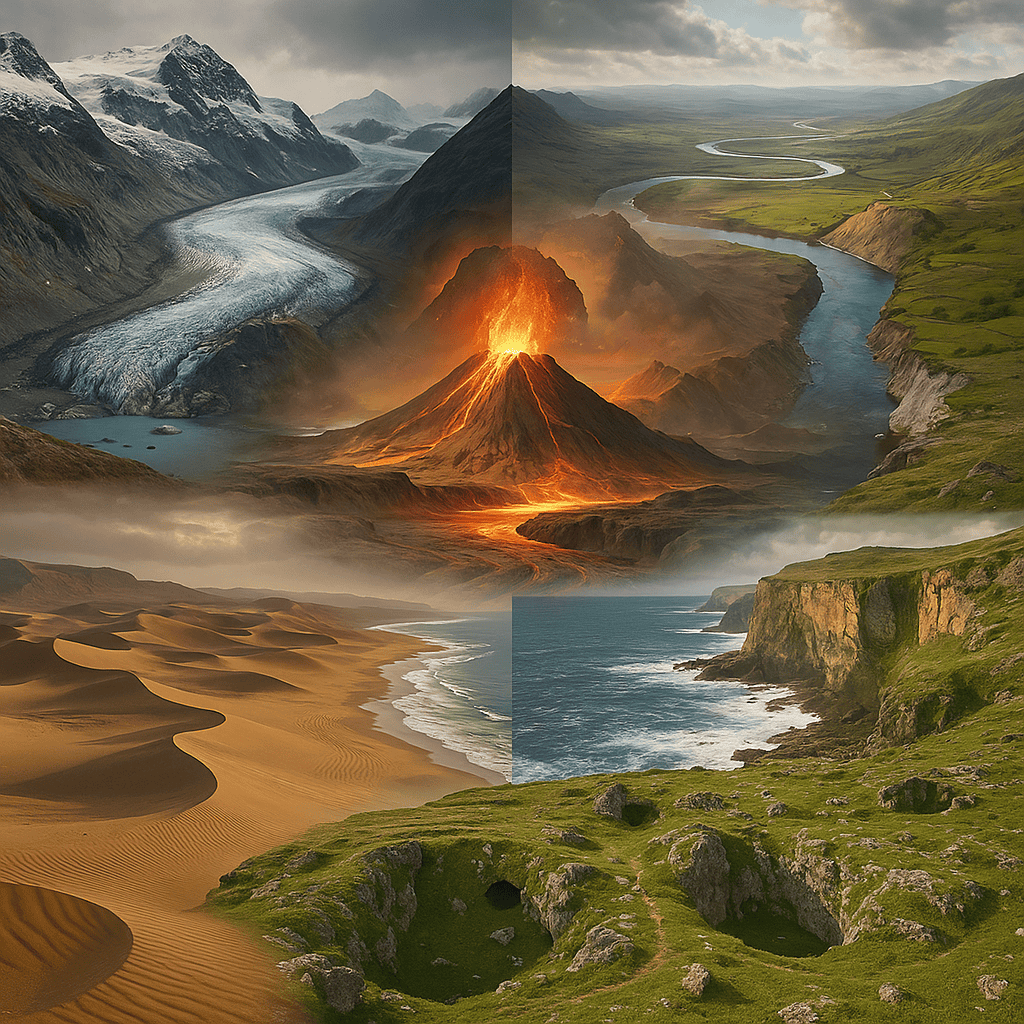

IV. Surface Processes and Landform Evolution

While the Earth’s interior builds mountains and drives eruptions, the surface is sculpted by exogenic processes—those powered by the Sun, gravity, wind, water, and ice. Over millions of years, these processes wear down even the highest peaks and build new landscapes from their remains. This constant reshaping is the domain of geomorphology, the science of landforms.

Weathering: Breaking Down the Old

Weathering is the breakdown of rocks at or near the Earth’s surface. It comes in three main forms:

- Physical (Mechanical) Weathering: Rocks crack and fragment through freeze-thaw cycles, salt crystallization, temperature changes, or biological activity (e.g., roots).

- Chemical Weathering: Minerals are dissolved or transformed by reactions with water, acids, and atmospheric gases (e.g., carbonation dissolving limestone).

- Biological Weathering: Organisms accelerate breakdown, such as lichen secreting acids or burrowing animals disturbing soil.

Weathering is essential for soil formation and nutrient cycling—and it sets the stage for erosion.

Erosion and Transport: Moving the Earth

Erosion is the removal of weathered material by agents such as:

- Water (rivers, rain, floods)

- Ice (glaciers carving valleys)

- Wind (desert deflation, dune formation)

- Gravity (landslides, rockfalls)

These forces transport sediment across landscapes and eventually deposit it in new settings.

Deposition and Landform Creation

As erosive agents lose energy, they deposit their loads, creating new landforms:

- Rivers form floodplains, deltas, and alluvial fans.

- Waves build beaches and coastal bars.

- Wind forms dunes and loess plains.

- Glaciers sculpt U-shaped valleys and deposit moraines.

The cycle of erosion, transport, and deposition builds and reshapes landforms across the globe, forming a dynamic surface mosaic.

Landform Systems

Some key landform systems include:

- Fluvial Landscapes – shaped by rivers and streams

- Coastal Landscapes – shaped by tides, waves, and currents

- Aeolian Landscapes – dominated by wind (e.g., deserts)

- Glacial Landscapes – formed by ice sheets and alpine glaciers

- Karst Landscapes – formed by chemical weathering of soluble rocks (e.g., limestone caves, sinkholes)

Each system reveals the interplay of climate, rock type, biological activity, and time.

Scientific Fields Involved

- Geomorphology: Interprets landform processes and their evolution

- Sedimentary Geology: Studies sediment layers, depositional environments, and fossil preservation

- Hydrogeology: Examines how surface water interacts with groundwater

- Environmental Geology: Assesses landscape stability and risk, including erosion control and land-use planning

Why It Matters

Surface processes govern where people can live, farm, and build. They determine the fertility of soil, the location of water sources, and the stability of slopes. They also carry risks—floods, landslides, coastal erosion, and desertification.

A deep understanding of landform evolution helps us mitigate these hazards, manage water and soil resources, and adapt to a changing climate. As stewards of Earth’s surface, we must work with its rhythms—not against them.

V. Earth’s History and the Record of Life

Beneath our feet lies a layered archive of deep time. Every stratum of rock preserves a fragment of Earth’s unfolding story—from barren volcanic wastelands to lush ancient forests, from microbial mats to the bones of dinosaurs. By studying this record, geologists reconstruct the vast narrative of planetary change and biological evolution.

The Geologic Time Scale

Earth’s history spans over 4.6 billion years, divided into hierarchical intervals:

- Eons (e.g., Phanerozoic, Proterozoic)

- Eras (e.g., Paleozoic, Mesozoic, Cenozoic)

- Periods (e.g., Jurassic, Carboniferous, Quaternary)

- Epochs and Ages

The geologic time scale was originally built through stratigraphy—the study of rock layers and their relative positions. Later, geochronology refined this scale using radiometric dating, measuring the decay of isotopes like uranium-238 and carbon-14 to calculate absolute ages.

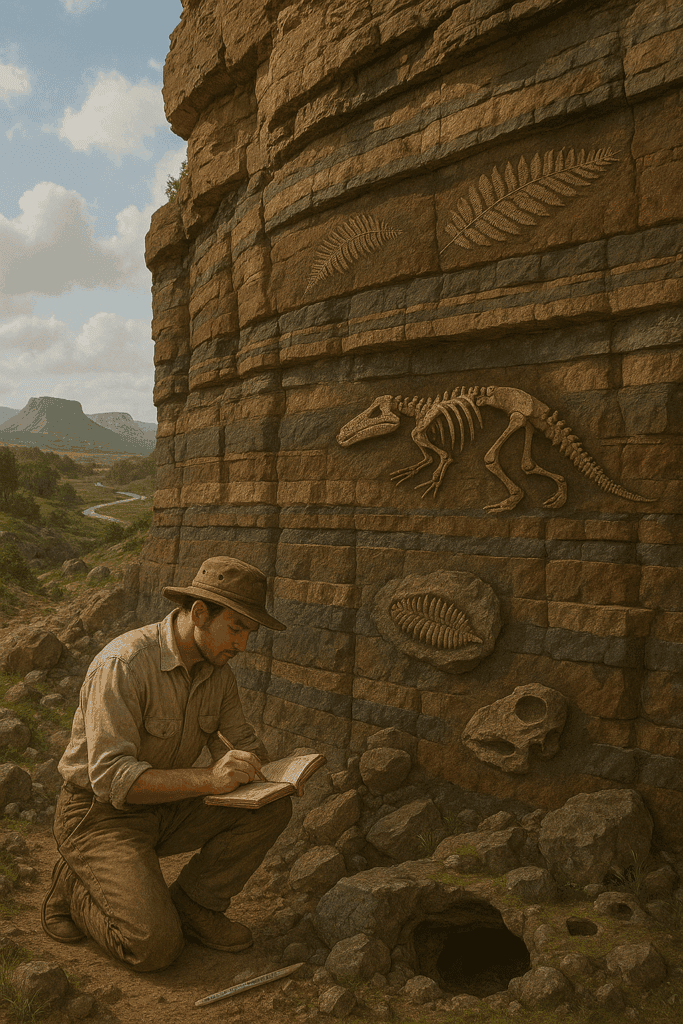

Fossils: Clues to the Living Past

Fossils—preserved remains, impressions, or traces of organisms—are the cornerstone of Earth’s biological history. They reveal:

- Species evolution and extinction

- Past ecosystems and climates

- Mass extinctions and recovery events

Major fossil-bearing formations, like the Burgess Shale or Morrison Formation, offer snapshots of life during different geologic periods. Even microfossils, like pollen or foraminifera, are vital for reconstructing ancient environments and tracking climate change.

Key Events in Earth’s Biological History

- ~3.5 billion years ago: Oldest known microbial life (stromatolites)

- ~2.5 billion years ago: Great Oxygenation Event, driven by photosynthesizing cyanobacteria

- ~541 million years ago: Cambrian Explosion—sudden diversification of multicellular life

- ~252 million years ago: Permian Extinction—the largest mass extinction

- ~66 million years ago: Chicxulub impact and the extinction of the dinosaurs

- ~2.6 million years ago to present: Quaternary Period, ice ages and rise of Homo sapiens

These events illustrate the interconnectedness of geological and biological processes: climate change, volcanism, asteroid impacts, and shifting continents all helped shape the course of life.

The Role of Geobiology

Geobiology bridges geology and biology by studying how life and Earth co-evolve. Microbes, for example, helped form the first sedimentary rocks and continue to influence rock weathering and mineral deposition. Meanwhile, Earth’s shifting surface provides habitats and selective pressures that guide evolution.

Scientific Fields Involved

- Paleontology: Reconstructs ancient life through fossil analysis

- Geochronology: Establishes the timing of evolutionary and geological events

- Stratigraphy: Maps and interprets sedimentary layers and sequences

- Geobiology: Investigates Earth-life interactions across time

Why It Matters

The fossil record offers context for the present biodiversity crisis and climate change. Understanding past mass extinctions, adaptation patterns, and ecosystem shifts helps forecast future possibilities. It also deepens our sense of belonging: humanity is not separate from Earth’s story—we are one of its most recent chapters.

In the strata of stone and bone, we find not only evidence of what has been, but also insight into what could be.

VI. Earth Resources and the Global Economy

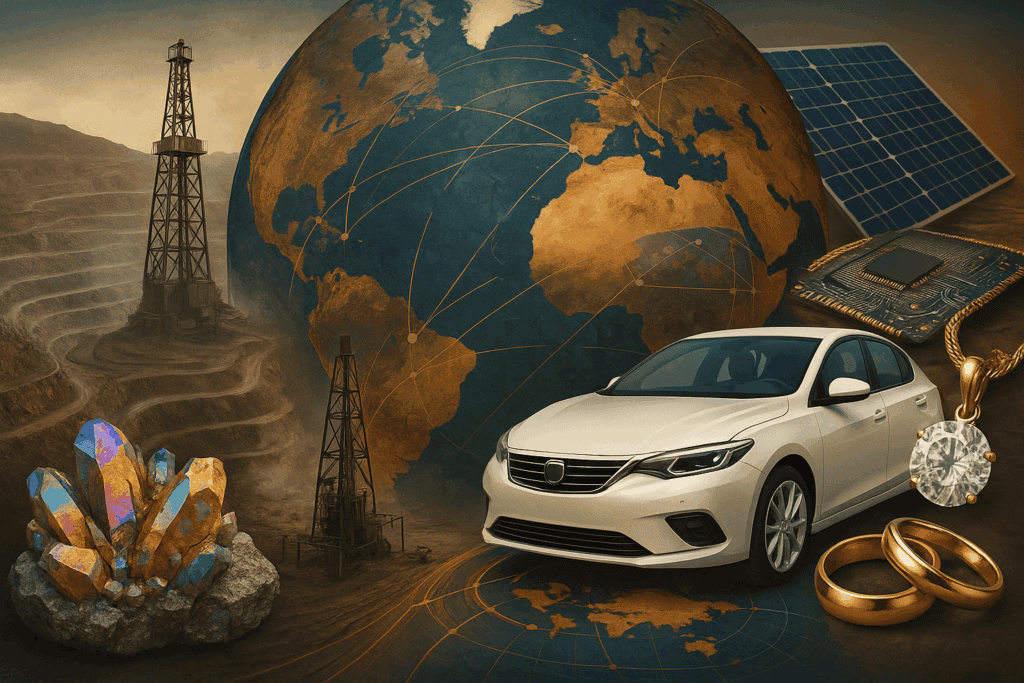

The Earth is rich in resources—energy, minerals, water, and fertile soil—that sustain life and drive human civilization. From the earliest stone tools to modern satellites and smartphones, everything we build and consume originates from geologic materials. Yet the extraction and use of these resources come with profound environmental, ethical, and geopolitical consequences.

Fossil Fuels: Ancient Sunlight

Fossil fuels—coal, oil, and natural gas—are derived from the remains of ancient organisms, buried and compressed over millions of years.

- Coal forms from ancient plant matter in swampy environments.

- Petroleum and natural gas originate from microscopic marine life deposited in anoxic seabeds.

These hydrocarbons power the global economy, but also contribute heavily to greenhouse gas emissions, climate change, and air pollution. Their extraction can devastate ecosystems and infringe on indigenous lands.

Key geological methods used in exploration include:

- Sedimentary basin analysis

- Seismic surveying

- Well-logging and core sampling

Metals and Industrial Minerals

Modern society relies on a wide array of metals and non-metallic minerals, including:

- Iron, copper, aluminum, nickel – for construction, electronics, and transportation

- Lithium, cobalt, rare earth elements – vital for batteries, renewable energy, and digital technology

- Phosphate and potash – essential for fertilizers

- Silica and clays – used in glass, ceramics, and industrial processes

These materials are mined through methods such as:

- Open-pit and underground mining

- Placer mining (river sediments)

- Solution mining (dissolving materials underground)

- Deep-sea mining (emerging, controversial)

The geological sciences—especially economic geology, mineralogy, and geophysics—identify, assess, and manage these resources.

Gems and Precious Metals

Gold, silver, diamonds, and other gemstones are more than just economic assets—they carry deep cultural, religious, and symbolic meaning. But their extraction often involves:

- Exploitation of labor and indigenous peoples

- Conflict financing (“blood diamonds”)

- Severe environmental degradation

Understanding the geologic processes behind these resources—such as hydrothermal mineralization or kimberlite pipe formation—aids in ethical sourcing and responsible trade.

Water and Soil: The Unsung Resources

Groundwater is a vital resource for agriculture, drinking water, and industry. Managed by hydrogeologists, aquifers must be protected from over-extraction, pollution, and salinization.

Soil, formed from weathered rock and organic matter, underpins agriculture and ecological health. Soil erosion and degradation are major threats to food security and biodiversity.

Global Impact and Geopolitical Dimensions

The distribution of resources is uneven, influencing global trade, economic power, and political conflict. Key examples:

- Oil in the Middle East

- Lithium in the “Lithium Triangle” (Chile, Bolivia, Argentina)

- Cobalt in the Democratic Republic of Congo

- Rare earths dominated by China

Resource-rich regions often face paradoxical poverty, instability, or environmental damage due to poor governance, corruption, or neocolonial extraction practices.

Scientific Fields Involved

- Economic Geology: Locates and evaluates economically valuable Earth materials

- Mineralogy: Identifies and characterizes minerals

- Environmental Geology: Assesses the impact of extraction and land-use

- Geotechnical Engineering: Supports infrastructure planning in resource-rich areas

- Hydrogeology: Manages and protects water resources

Ethics and Management: An Integrated Humanist View

From an Integrated Humanist perspective, Earth’s resources must be viewed not merely as commodities, but as shared inheritances:

- Stewardship over exploitation

- Sustainable yield rather than extraction at all costs

- International cooperation over resource competition

- Transparency and fairness in trade and labor

- Restoration and remediation after use

Geology, properly applied, can support not only industrial progress but also ecological integrity, social justice, and long-term planetary stability.

VII. The Politics of the Earth

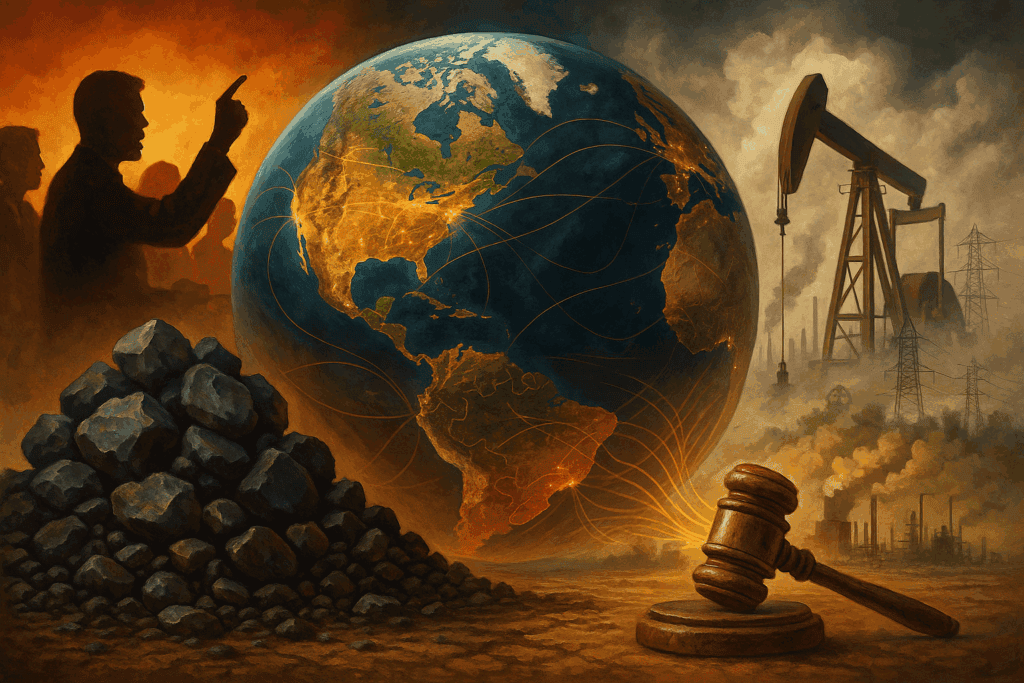

Geology is not just a science—it is a source of power. Earth’s resources and the risks embedded in its terrain influence geopolitics, economics, public policy, and international relations. As demand for minerals, energy, and land increases, so do the political tensions and ethical challenges surrounding their control.

Strategic Resources and Global Tensions

Certain geologic resources—particularly oil, gas, uranium, rare earth elements, lithium, and freshwater—are considered strategic because they are vital to national security, technology, and economic development. Control over these resources can shape alliances, wars, and trade policies.

Examples include:

- OPEC’s influence on global oil prices

- China’s dominance in rare earth exports

- Russia’s leverage through gas pipelines to Europe

- Disputes over Arctic drilling rights and seabed minerals

- Conflicts in the Sahel and Congo over gold, cobalt, and coltan

These resources are often concentrated in politically unstable or ecologically fragile regions, where extraction fuels conflict, corruption, and exploitation.

Environmental Justice and Extraction

The costs of geological extraction are rarely borne equally. Indigenous communities, rural populations, and vulnerable ecosystems often suffer the consequences of mining, drilling, and large-scale land alteration. Common issues include:

- Land dispossession and displacement

- Pollution of air, water, and soil

- Health crises in mining regions

- Loss of biodiversity and sacred landscapes

Environmental justice movements seek to ensure that these communities have a voice in resource decisions, fair access to benefits, and protections against harm.

Infrastructure, Development, and Risk

Geology underpins infrastructure—roads, bridges, dams, tunnels—but poor geological assessment can lead to catastrophic failures. Geotechnical engineers use subsurface data to ensure stability, particularly in earthquake-prone or flood-prone regions.

Moreover, the political management of natural hazards is a vital part of governance. Countries that invest in geological monitoring and disaster mitigation reduce loss of life and economic disruption. This includes:

- Earthquake-resistant building codes

- Volcano monitoring and evacuation planning

- Flood and landslide hazard mapping

Disasters are natural; disasters turning into catastrophes are political.

Climate Change and the Geological Lens

Climate change is now a central geopolitical concern, and geology offers tools to understand and address it:

- Paleoclimatology reveals how Earth’s climate has shifted over time

- Carbon sequestration technologies are grounded in sedimentary geology

- Sea-level rise and coastal erosion require geomorphological and engineering solutions

Climate action is deeply entwined with geology—not only in understanding the past, but in navigating the future.

Toward a New Geological Diplomacy

A sustainable future demands international agreements informed by geology:

- Cross-border water sharing agreements

- Resource certification and transparency (e.g., EITI, Kimberley Process)

- Ban or regulation of ecologically damaging mining (e.g., deep-sea mining moratoria)

- Geological education and cooperation in developing nations

Treaties, scientific collaborations, and global geological surveys could serve as foundations for peace, rather than sources of competition and exploitation.

Scientific Fields Involved

- Environmental Geology: Evaluates environmental risks and land-use implications

- Economic Geology: Tracks resource locations and extraction impacts

- Geopolitics and Resource Geography (interdisciplinary): Maps and analyzes political control of resources

- Geotechnical Engineering: Assesses ground suitability for development

- Paleoclimatology and Climate Geology: Contextualizes global climate systems

Ethical Governance and Planetary Stewardship

Geology must no longer serve only markets and empires. From an Integrated Humanist standpoint, Earth’s geologic wealth is a global commons—a shared planetary endowment to be managed with humility, cooperation, and foresight.

To politicize the Earth ethically is to:

- Prioritize long-term planetary health over short-term gains

- Promote science-based policy and global data sharing

- Respect indigenous knowledge and sovereignty

- Advance universal access to clean water, safe housing, and resource equity

In this view, geology becomes not just the science of what lies beneath—but a guide to what should rise above.

VIII. Geology Beyond Earth

Geology does not end at Earth’s surface. The same processes that shape our planet—volcanism, impact cratering, tectonics, erosion, and mineral formation—operate across the solar system. The study of planetary geology allows us to view Earth in a cosmic context, expanding our understanding of how planets evolve, what conditions support life, and what resources may lie beyond.

The Solar System as a Laboratory

Every planetary body tells a different geological story:

- The Moon reveals a history of massive impacts, volcanic plains, and tectonic quiescence.

- Mars displays extinct volcanoes (Olympus Mons), vast canyons (Valles Marineris), and ancient riverbeds—suggesting a wetter past.

- Venus shows evidence of intense volcanism and a resurfaced crust, despite its extreme greenhouse climate.

- Icy moons like Europa and Enceladus host subsurface oceans beneath crusts of ice, where cryovolcanism and tidal forces sculpt alien landscapes.

These celestial objects provide case studies in planetary differentiation, mantle dynamics, and surface evolution under varying conditions of gravity, atmosphere, and temperature.

Comparative Planetology and Earth’s Uniqueness

By studying other worlds, geologists refine their understanding of Earth’s special characteristics:

- Earth has plate tectonics—so far, a unique feature enabling the carbon cycle and long-term climate stability.

- Earth hosts liquid water on its surface, supporting a biosphere with geochemical feedback loops.

- Earth’s magnetic field shields the surface from harmful solar radiation.

Comparative analysis highlights how geology and habitability are intertwined—and reminds us how rare and fragile our home may be.

Astrobiology and the Search for Life

Astrobiology investigates the potential for life on other planets. Geology is central to this quest, because life depends on:

- Water-rock interactions

- Stable environments for complex chemistry

- Energy gradients (from volcanism, radiation, or chemical disequilibrium)

For example, Mars rovers search for clay minerals and sedimentary layers that could preserve signs of past microbial life. Ocean worlds like Europa and Titan intrigue scientists seeking life in subsurface seas.

Space Mining and the Future Economy

With dwindling Earth resources, some envision asteroid mining and lunar resource extraction as future solutions. Targets include:

- Water ice (for fuel and life support)

- Platinum group metals (for electronics)

- Helium-3 (hypothetical fusion fuel)

Planetary geologists assess these resources by studying meteorites, remote sensing data, and robotic landers.

However, ethical and environmental frameworks for extraterrestrial extraction are still in their infancy—and face concerns of inequality, environmental risk, and the militarization of space.

Scientific Fields Involved

- Planetary Geology: Applies Earth-based geological principles to other celestial bodies

- Astrobiology: Combines geology, biology, and chemistry to search for extraterrestrial life

- Remote Sensing and Geophysics: Map planetary surfaces and interiors from orbit

- Exogeochemistry: Studies the chemistry of alien rocks and atmospheres

- Comparative Planetology: Synthesizes geological data across planets for broader insights

Why It Matters

Exploring the geology of other worlds inspires new technologies, reframes our understanding of Earth, and fuels the imagination. It challenges us to think not only about how we came to be—but how life might arise elsewhere.

Yet perhaps the greatest gift of planetary geology is perspective: when we look out into the cosmos, we see that Earth is not just a planet—it is a precious, living world, uniquely suited to nurture life. To explore beyond Earth is also to better appreciate and protect the one we already have.

IX. Geology and the Future of Humanity

Geology is more than the study of ancient stones and distant epochs. It is a vital tool for shaping the human future. From managing climate change and securing clean water to building resilient cities and fostering peace, geology helps humanity understand the ground it walks on—literally and metaphorically.

The Age of the Anthropocene

We are now living in what many scientists call the Anthropocene—a new geological epoch marked by the planetary impact of human activity. Hallmarks include:

- Atmospheric carbon spikes from fossil fuel use

- Mass extinction rates far above background levels

- Plastic and radioactive signatures in sediment layers

- Accelerated erosion, deforestation, and aquifer depletion

Geologists are uniquely positioned to assess these transformations, measure their global scope, and identify tipping points. But with that knowledge comes responsibility.

Geological Challenges of the 21st Century

Humanity faces urgent geological and geotechnical challenges:

- Climate Adaptation: Coastal erosion, sea-level rise, and melting permafrost require new land-use strategies and infrastructure designs.

- Disaster Preparedness: Earthquake-resistant cities, volcanic monitoring systems, and landslide early warnings save lives.

- Resource Transition: Moving away from fossil fuels demands new methods of finding, managing, and recycling critical minerals.

- Urban Expansion: Cities must be built on safe ground, with sustainable access to water, energy, and construction materials.

- Geoengineering and Carbon Sequestration: These controversial technologies rely on precise geologic knowledge of subsurface stability and fluid behavior.

Every major problem humanity faces is, at some level, a geological problem.

Education, Equity, and Global Science

To rise to these challenges, we must democratize geologic knowledge:

- Public education should include basic earth sciences as part of civic literacy.

- Underserved regions must gain access to geotechnical expertise to reduce vulnerability to natural hazards.

- International data-sharing and collaboration must replace extraction-driven competition with open-science cooperation.

Geology must become a tool of solidarity, not supremacy.

Integrated Humanism and Earth Stewardship

From an Integrated Humanist perspective, geology offers both a warning and a guide.

The warning: Civilization depends on the careful use of finite resources and fragile ecosystems. If we ignore geologic limits, we risk collapse.

The guide: By aligning policy with planetary science, humanity can build an ethical and resilient global civilization. This requires:

- Holistic governance based on long-term planetary cycles

- Global resource management that prioritizes regeneration over depletion

- Reverence for Earth’s systems and respect for indigenous wisdom

- A shared geological literacy as a foundation for peace and planning

Geology is not just about the past. It is the science of continuity, consequence, and connection—bridging billions of years to the choices we make today.

Conclusion: Grounded in the Future

In the end, geology teaches humility and hope.

Humility: because we stand on the remains of ancient oceans, extinct volcanoes, and forgotten forests.

Hope: because through understanding the Earth, we gain the wisdom to protect it—and perhaps to flourish within its bounds.

The rocks beneath us are not silent. They tell the story of Earth’s birth, evolution, and possibility. If we listen closely, they can also help us write the next chapter—a future of balance, beauty, and belonging on this precious, living planet.