Table of Contents

1. Introduction – The Engine Behind the World

A brief overview of what mechanics is, and why it matters to both nature and human civilization.

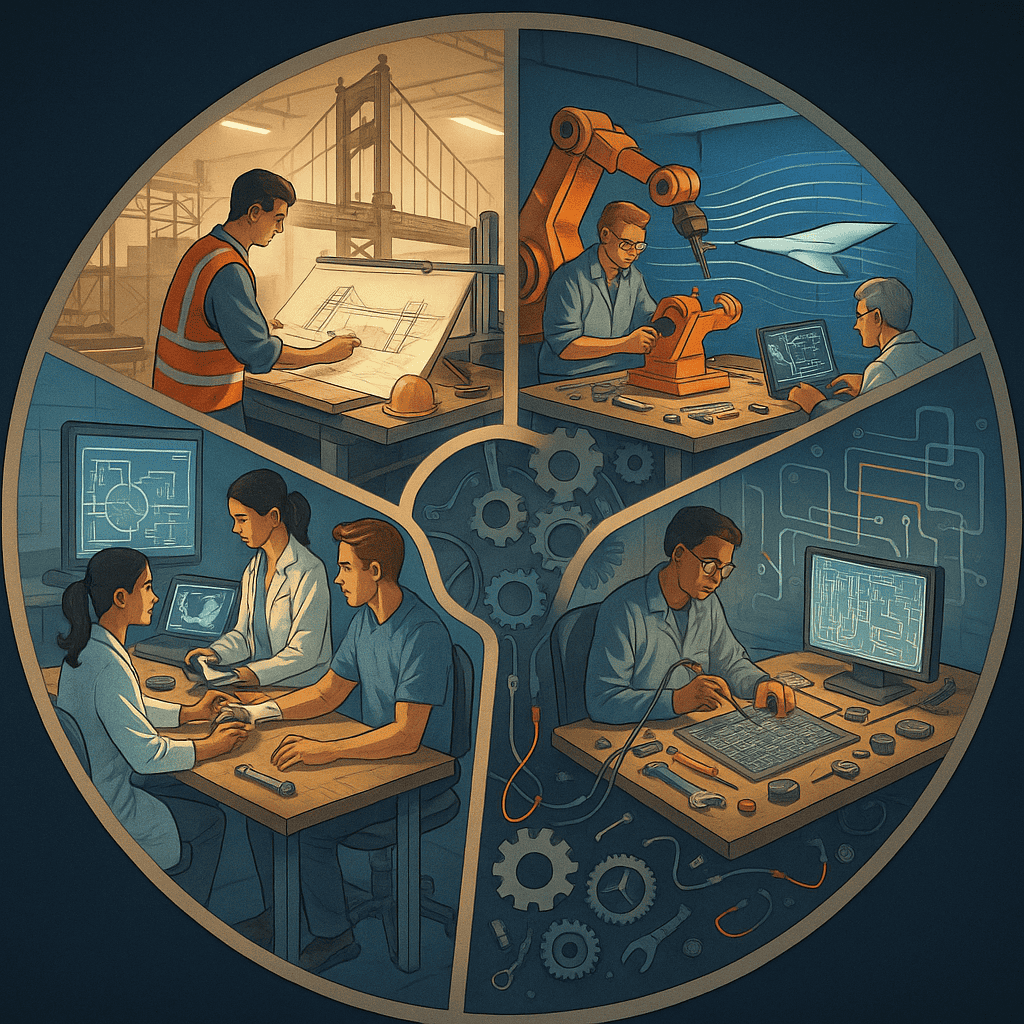

2. What Is Engineering? – Designing the Possible

Definition of engineering, its role in society, and a survey of major branches: mechanical, civil, electrical, aerospace, biomedical, and systems engineering.

3. Defining Mechanics – The Study of Force and Motion

A clear, structured definition of mechanics as a branch of physics and engineering. Overview of the main subfields: statics, dynamics, kinematics, and fluid mechanics.

4. Mechanics in Nature – The Great Machine of the Universe

How mechanics manifests in nature: gravity, planetary motion, animal locomotion, tectonic movements, atmospheric dynamics, etc.

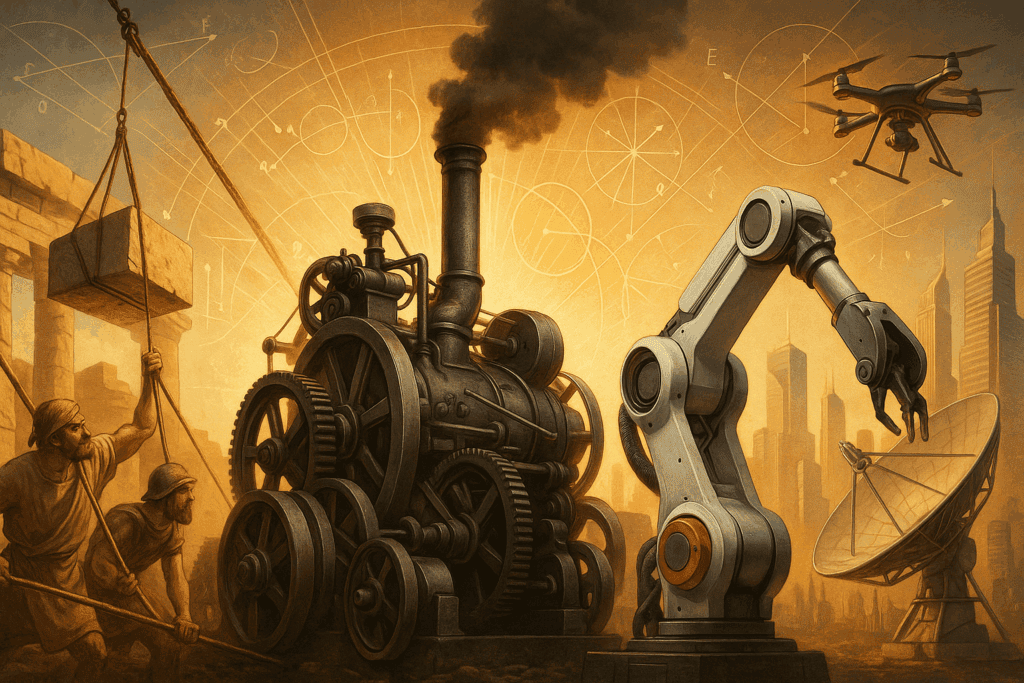

5. A History of Mechanics – From Levers to Lasers

A narrative from ancient Mesopotamian wheels and Greek thinkers (Archimedes, Aristotle), through Newton and Galileo, to the Industrial Revolution, 20th-century engineering marvels, and future robotics and space mechanics.

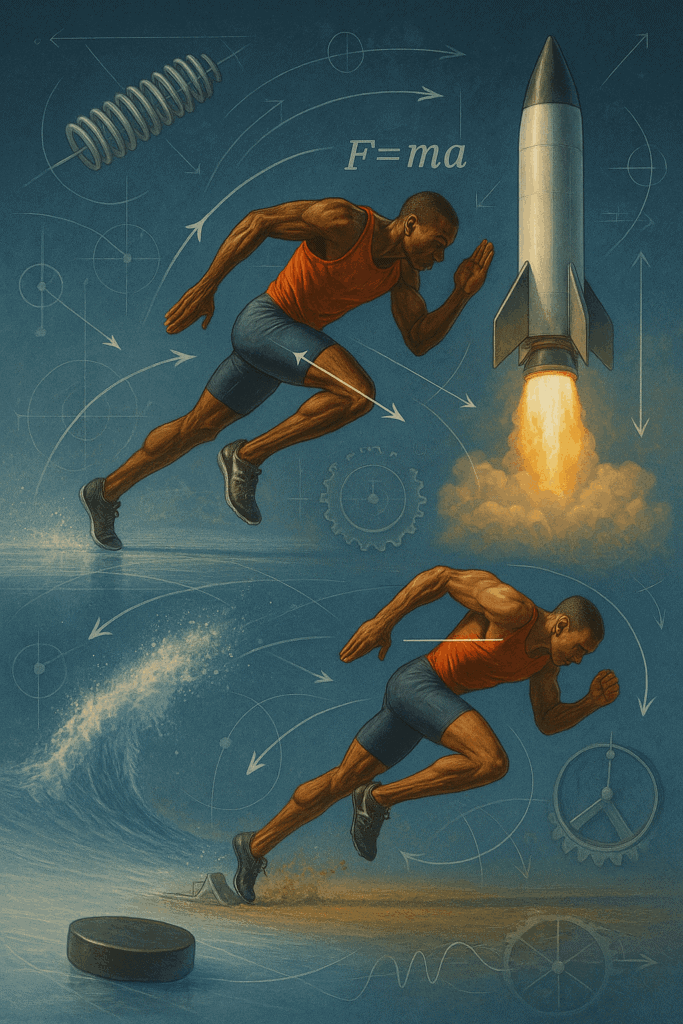

6. The Basic Principles of Mechanics – Laws That Move the World

Newton’s Laws, conservation of momentum and energy, force diagrams, torque, friction, elasticity, equilibrium, and mechanical advantage.

7. Invention and Innovation – The Machines That Changed Us

Comprehensive survey of mechanical inventions: the wheel, screw, pulley, clockwork, printing press, internal combustion engine, elevators, industrial machines, engines, robots, and more.

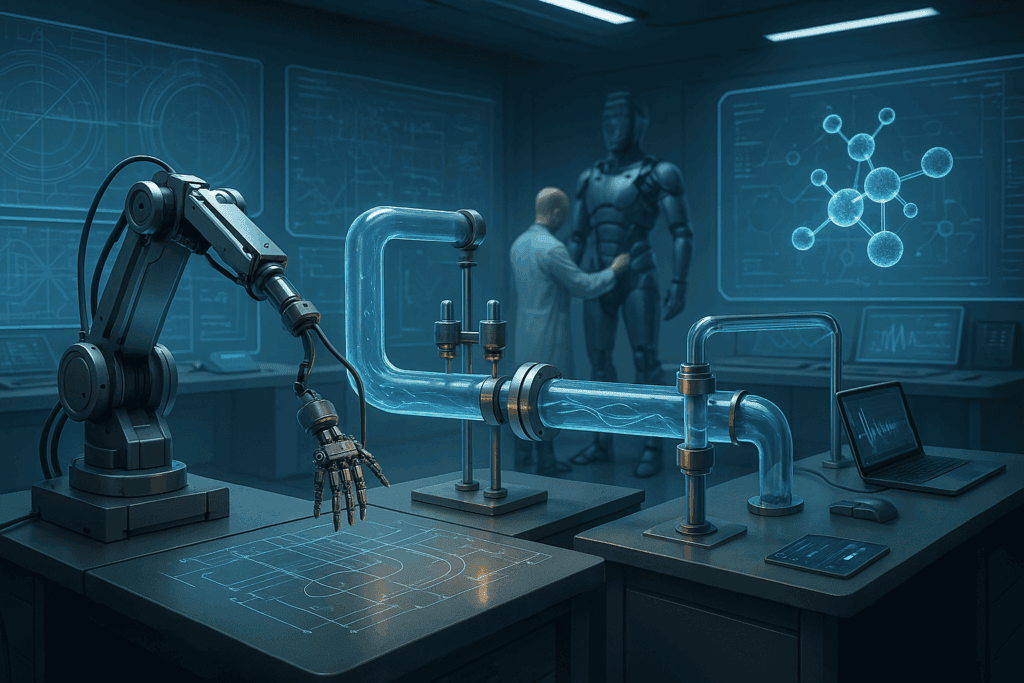

8. Mechanics and Other Sciences – Interconnected Systems

How mechanics interrelates with electronics (mechatronics), thermodynamics, material science, biology (biomechanics), and modern systems theory.

9. The Future of Mechanics – Intelligent Machines and Beyond

Trends in robotics, nanomachines, space-based mechanical systems, sustainable engineering, and how AI is transforming mechanical design and function.

10. Feature – The Rise of Self-Repairing Machines

No service call. No human hands. Just built-in awareness, diagnostics, and a mechanical immune system.

11. Conclusion – Mechanics as Human Heritage and Scientific Bedrock

Summing up the importance of mechanical understanding for civilization, education, sustainability, and global progress.

1. Introduction – The Engine Behind the World

Take a look around you. Every object in motion—every car on the road, elevator in a shaft, jet overhead, or robot in a lab—is working because of one thing: mechanics. This is the science that explains how things move, how forces act, and how machines turn ideas into action. It’s one of the oldest branches of science, and still one of the most powerful.

Before there were apps and algorithms, there were wheels and pulleys. Thousands of years ago, engineers in Egypt were stacking stone with levers and ropes. The Greeks were breaking problems into principles. Later, Galileo and Newton cracked the code of motion, writing laws that still guide everything from roller coasters to rocket launches.

Mechanics isn’t just ancient history. It’s everywhere—running through every field of engineering, embedded in the bones of every machine. You’ll find it in the legs of a galloping horse, the suspension of a mountain bike, the joints of a Mars rover. It’s in skyscrapers that stand firm against the wind, and in micro-robots that can swim through a human artery.

In this article, we’ll break down how mechanics works—from basic concepts like force and torque to cutting-edge applications in robotics and aerospace. We’ll explore its natural roots, trace the major milestones in mechanical invention, and look ahead to the future of smart machines and self-building systems.

Mechanics is more than just physics. It’s motion, power, and possibility—and it’s still shaping the world every day.

2. What Is Engineering? – Designing the Possible

Engineering is where science meets real life. It’s the profession—and the mindset—that turns principles into prototypes and theory into working machines. Engineers don’t just study how things work; they build things that do work.

At its core, engineering is about solving problems. Want to lift a heavy load, move faster, fly higher, or live more efficiently? An engineer figures out how. That might mean designing a bridge to hold traffic through a blizzard, creating a robotic arm that mimics human movement, or building a satellite that orbits for decades without a glitch.

There isn’t just one kind of engineering. There are many, and each tackles a different layer of how we live:

- Mechanical Engineering is the classic kind—dealing with machines, engines, tools, and movement.

- Civil Engineering covers the big stuff: roads, bridges, water systems, and infrastructure.

- Electrical Engineering powers everything from your phone to the power grid.

- Aerospace Engineering takes mechanics to the sky and beyond—airplanes, rockets, satellites.

- Biomedical Engineering blends mechanics with biology, building prosthetics, surgical tools, and medical machines.

- Systems Engineering pulls it all together, ensuring complex technologies work as a unit.

And that’s just the start. There are also environmental, software, nuclear, and materials engineers—each field zooming in on a different set of challenges, but all grounded in the same core principle: use science to design solutions.

What ties all engineering disciplines together is mechanics. Whether it’s figuring out the tension in a suspension cable or the airflow over a drone wing, every engineer has to understand how forces interact, how energy moves, and how materials respond. Mechanics is the shared language.

In other words, mechanics is the grammar of engineering—and engineering is the way we write our story on the physical world.

3. Defining Mechanics – The Study of Force and Motion

So what exactly is mechanics?

In plain terms, mechanics is the science that explains how things move—and why. It’s the study of forces, motion, energy, and the interactions between objects. Whether you’re pushing a shopping cart or launching a rocket, you’re working within the rules of mechanics.

At its heart, mechanics answers questions like:

- What happens when you apply a force to an object?

- Why do some things move smoothly while others resist?

- How do you make systems stable—or deliberately unstable?

- What keeps a building standing, a car from tipping, or a planet in orbit?

Scientists break mechanics into a few key categories:

- Statics is all about balance. It studies objects at rest—like buildings, bridges, or shelves—and how forces hold them still without tipping or breaking.

- Dynamics covers motion. It looks at objects in motion, including acceleration, collisions, and the interplay of mass and velocity.

- Kinematics zooms in on motion itself—how fast something moves, along what path, and with what kind of twist or rotation—without worrying (yet) about the forces that cause it.

- Fluid Mechanics gets into liquids and gases, from hydraulic systems to air currents. (Yes, fluids follow mechanical laws too—even clouds and blood flow are mechanical systems.)

Classical mechanics, which came out of the work of Newton and Galileo, still forms the core of mechanical science today. But over the centuries, mechanics has expanded—into quantum mechanics (tiny particles), relativistic mechanics (high-speed objects), and computational mechanics (modeled systems using software).

The amazing thing? The same fundamental rules apply across the board. From a dropped ball to an interplanetary probe, motion follows predictable laws. Mechanics gives us the tools to understand those patterns—and to design machines that work with, not against, the forces of nature.

It’s a science of simplicity and power. Push something, and it moves. Unless something pushes back.

4. Mechanics in Nature – The Great Machine of the Universe

Before we ever built engines or drew diagrams, mechanics was already in motion—shaping mountains, steering planets, and powering the muscles of every living thing. Nature didn’t wait for human engineers to understand mechanics. It is mechanics.

Start big: the cosmos runs on mechanical principles. Gravity pulls planets into orbit, spins galaxies into spirals, and flings comets through space. Earth’s rotation, the tides, eclipses, and even the wobble of the moon are all part of a massive, intricate machine—and every motion obeys the same physical laws.

Zoom in to Earth, and you’ll see mechanics at work in plate tectonics. The continents drift, mountains rise, and earthquakes shake the ground—all because of mechanical forces deep in Earth’s mantle pushing and shifting solid rock over time.

In the sky, air moves in complex currents. Hurricanes spin with the mechanics of angular momentum. Birds ride thermals like engineers of instinct, adjusting wing shape to generate lift and glide with aerodynamic efficiency that rivals our best aircraft.

In the ocean, waves and currents follow the same rules of fluid mechanics we use in designing submarines. Fish, octopuses, and whales have evolved bodies that exploit water flow for propulsion, balance, and maneuverability.

Even at the scale of biology, mechanics plays a central role. Muscles work by contracting fibers to pull on bones—levers in a biological machine. Joints pivot, spines flex, hearts pump. Evolution is full of brilliant mechanical designs: the spring-loaded jaws of a trap-jaw ant, the shock-absorbing legs of a cheetah, the hydraulic motion of spider limbs.

Nature didn’t need blueprints. It arrived at mechanical solutions through billions of years of trial and error. Every living thing that moves has mastered some aspect of force, balance, motion, or pressure.

When we study mechanics in nature, we’re not just doing science—we’re reverse-engineering life itself.

5. A History of Mechanics – From Levers to Lasers

Mechanics has been around a lot longer than we’ve had a name for it. Before scientists gave us equations, ancient builders and inventors were already putting the principles into practice—lifting, rolling, hammering, balancing, and building.

The earliest machines were simple: the lever, the wheel, the pulley, and the inclined plane. They didn’t need power sources—just gravity, muscle, and clever arrangement. In ancient Egypt, workers used levers and ramps to build pyramids. In Mesopotamia, wheels and gears appeared in water-lifting devices and carts.

Archimedes, the Greek polymath of the 3rd century BCE, was one of the first to write down the rules. He figured out the mathematics of levers, buoyancy, and pulleys. Legend has it he once said, “Give me a place to stand, and I will move the Earth.”

But it wasn’t until the Scientific Revolution that mechanics became a full-fledged science. In the 1500s and 1600s, Galileo Galilei conducted experiments on motion—rolling balls down ramps to understand acceleration. Isaac Newton took it further, publishing his Principia Mathematica in 1687, laying out the three famous laws of motion and the universal law of gravitation. With Newton, mechanics wasn’t just for gears and bridges anymore—it was the operating system of the universe.

The Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries turbocharged everything. Engineers applied mechanics to build steam engines, looms, trains, and turbines. Mechanical invention became the backbone of progress. Factories, cities, and entire industries rose around the new mechanical mastery.

In the 20th century, mechanics joined forces with electricity, chemistry, and computing. Airplanes, cars, skyscrapers, space rockets—all emerged from the expanding toolbox of applied mechanics. Even at the atomic level, quantum mechanics started redefining our understanding of matter and energy.

Now, in the 21st century, we’re engineering machines that can walk, swim, fly, and think. Robotics, nanotechnology, biomechanics, and artificial intelligence are opening new frontiers where mechanical design meets smart systems. The tools are smaller, faster, and more precise—but the principles still echo those ancient insights: balance, force, motion, resistance, and control.

Mechanics may be an ancient discipline, but it has always moved forward. Literally.

6. The Basic Principles of Mechanics – Laws That Move the World

No matter how complex the machine, how advanced the robot, or how epic the rocket launch, all of mechanics boils down to a few simple rules. These are the basic principles—timeless, universal, and surprisingly elegant.

Let’s break them down:

Newton’s Three Laws of Motion

These are the pillars. Everything else builds on them.

- An object in motion stays in motion unless acted on by a force.

Translation: If nothing gets in the way, things keep moving. That’s inertia. - Force equals mass times acceleration (F = ma).

Push something heavier, or push it faster, and you’ll need more force. - Every action has an equal and opposite reaction.

Push on something, and it pushes back. Rockets fly by pushing exhaust down. You walk by pushing the ground behind you.

Energy and Work

- Work happens when a force moves something. Push a box across a room? That’s work.

- Energy is the capacity to do work. It comes in many forms—kinetic (movement), potential (stored), thermal (heat), and more.

- Conservation of Energy says it doesn’t disappear—it just changes form. A falling rock’s potential energy becomes kinetic. A spring’s tension becomes motion.

Momentum

- Momentum = mass × velocity.

The heavier and faster something is, the harder it is to stop. - Like energy, momentum is conserved. In collisions, it transfers—even in a cue ball break or a car crash.

Friction and Resistance

- Friction is what makes things slow down. It’s why tires grip the road and why engines need oil.

- Air resistance, drag, and mechanical wear all eat away at energy—unless you engineer around them.

Torque and Rotational Motion

- Torque is the rotational version of force. It’s what makes wheels spin or bolts tighten.

- The farther from the pivot point you apply a force, the more torque you generate. That’s why wrench handles are long.

Equilibrium and Stability

- A system is in equilibrium when all forces balance. It’s not moving—or it’s moving steadily.

- Engineers rely on equilibrium to keep bridges standing, drones hovering, and satellites in stable orbits.

These principles aren’t just for scientists—they’re what let bikes balance, planes fly, elevators lift, and engines roar. And once you understand them, the whole world starts to make more sense.

Next time you throw a ball, ride a roller coaster, or tighten a bolt, remember: you’re using Newton’s toolbox.

7. Invention and Innovation – The Machines That Changed Us

Every era of human history can be traced by its machines.

From hand tools to high-speed trains, mechanical invention is what turned us from hunter-gatherers into farmers, from villagers into astronauts. Mechanics doesn’t just explain how machines work—it makes them possible in the first place.

Let’s take a ride through the greatest hits.

The Classics

- The Wheel – Invented around 3500 BCE, the wheel gave humanity its first real mechanical advantage. Add an axle and you’ve got a cart. Add gears and you’ve got a watch.

- The Lever and Pulley – Used by ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Chinese engineers to move heavy stones, lift water, and build impossible monuments.

- The Screw – Archimedes’ screw could lift water uphill. Today, it’s in everything from bottle caps to industrial compressors.

- The Inclined Plane – Ramps reduce the force needed to move heavy objects. The principle shows up in truck beds, wheelchair access, and even screw threads.

Medieval Ingenuity

- The Clock – Mechanical clocks in medieval Europe brought precision to timekeeping. Gears, escapements, pendulums—timing became engineering.

- Windmills and Waterwheels – Ancient green energy. These machines converted natural motion into usable work for grinding grain, pumping water, and powering looms.

The Industrial Revolution

- The Steam Engine – In the 1700s, James Watt supercharged the idea. Suddenly we had trains, factories, and mechanical labor on a global scale.

- The Internal Combustion Engine – Fire inside a cylinder—controlled explosions that power nearly every car, motorcycle, and plane in the 20th century.

- The Elevator – Elisha Otis’ safety brake made skyscrapers possible. Without elevators, no modern city skyline.

Modern Marvels

- The Automobile – Mechanics in motion. A car is basically a symphony of parts: pistons, crankshafts, axles, brakes, shocks, gears—and all of it obeying the laws of motion.

- The Airplane – Thanks to the Wright brothers and decades of aerodynamic tweaking, we now soar at 35,000 feet on machines made of wings, engines, and lift equations.

- The Robot – Mechanical limbs powered by software brains. From factory arms to humanoid machines, robotics is mechanics meeting intelligence.

The Microscopic and the Cosmic

- Nanomachines – Molecular-scale mechanical devices that could deliver drugs, repair tissue, or build tiny structures atom by atom.

- Spacecraft – From the Voyager probes to the James Webb Space Telescope, these are machines that withstand vacuum, radiation, and deep-space mechanics.

Every invention is a leap forward—but it’s built on centuries of mechanical insight. The wheel turned into the jet engine. The gear turned into the gyroscope. The pulley turned into the launch gantry.

Innovation is mechanical imagination—turned real.

8. Mechanics and Other Sciences – Interconnected Systems

Mechanics may be its own branch of science, but it never works alone.

In the real world, everything is interconnected. Machines don’t exist in isolation—they operate in environments full of energy, data, living systems, and moving parts. That’s why modern mechanics blends with other sciences to form powerful hybrids.

Electronics + Mechanics = Mechatronics

This is where hardware meets circuits. Mechatronics combines mechanical systems with electronics and control systems—think smart motors, sensors, robotic arms, and drones.

Your washing machine? Mechatronics. Anti-lock brakes in your car? Mechatronics. A Mars rover? Definitely.

Mechanics + Biology = Biomechanics

Nature is full of engineering—so biomechanics studies how living things move and interact with forces. From the stride of a racehorse to the grip of a prosthetic hand, this field fuels innovations in sports science, orthopedics, wearable tech, and even surgical robots.

Want to design a robot that walks like a cat? You’ll need to understand both mechanical torque and feline anatomy.

Mechanics + Thermodynamics

Heat is energy—and mechanics explains how that energy moves. Engines, turbines, and refrigerators all rely on a mix of thermal and mechanical systems. Even internal combustion engines are really heat engines at their core.

The more efficiently we convert heat into motion, the better our machines get. That’s what keeps energy science and mechanics tightly linked.

Mechanics + Materials Science

Not all matter behaves the same. Some bend, some bounce, some break. Mechanics helps us understand how materials respond to stress, strain, and pressure—while materials science finds better ones to build with: lighter, stronger, smarter.

Titanium bike frames? Carbon fiber wings? Heat-resistant ceramics in a jet engine? That’s where these two sciences team up.

Mechanics + Computing

Computational mechanics uses software to simulate stress, deformation, and dynamic motion in virtual space—before anything’s built. Engineers can now design bridges, aircraft, and implants entirely in digital 3D, testing real-world forces in virtual models.

Throw in AI, and you get machines that can adapt and optimize their own movement in real time.

Mechanics is no longer just about nuts and bolts. It’s part of a vast scientific ecosystem—connected to code, biology, chemistry, materials, and more.

The smarter our world gets, the more mechanics becomes the connective tissue that holds it all together.

9. The Future of Mechanics – Intelligent Machines and Beyond

We’ve come a long way from levers and pulleys. The next chapter in mechanics won’t just be about moving parts—it’ll be about parts that can think, learn, and even build themselves.

Welcome to the age of intelligent mechanics.

Smart Machines

Machines are getting brains. Embedded sensors, feedback loops, and AI algorithms allow devices to respond to real-time data. A smart prosthetic leg can adjust stride on the fly. A robotic warehouse arm can adapt to shifting loads.

Autonomous vehicles? They’re rolling physics labs—reading road conditions, calculating acceleration and torque, reacting in milliseconds. Mechanics + software = autonomy.

Bio-Inspired Engineering

Nature’s mechanical designs are far more advanced than ours in many ways. Engineers are reverse-engineering them.

- Gecko feet inspire adhesive materials.

- Bird wings guide drone design.

- Octopus arms lead to soft robotics—machines that bend, stretch, and flex like muscle and skin.

The line between machine and organism is getting thinner.

Miniaturization and Nanomechanics

Think small. Really small.

Nanomachines—mechanical systems measured in billionths of a meter—could one day repair cells, deliver medicine, or clean up pollution molecule by molecule. These aren’t science fiction anymore: early-stage nanoactuators and nanosensors already exist in labs.

Even at that scale, mechanics still rules. Forces, vibrations, and motion don’t disappear—they just get weirder.

Mechanics in Space

Space isn’t empty—it’s full of mechanical challenges.

Satellites need precise orientation. Telescopes deploy with millimeter accuracy. Planetary landers have to fold, unfold, shield, balance, and dig. Engineers now design systems to survive radiation, vacuum, freezing cold, and cosmic dust—all with no chance of repair.

Next up? Self-replicating machines that mine asteroids and build habitats. Long-term Mars missions with autonomous robots. Mechanics for the final frontier.

Sustainable Mechanics

The future also demands greener machines. That means more efficient engines, less mechanical waste, and systems designed for durability and repair.

Look out for regenerative braking systems, wind turbine mechanics, and materials that heal themselves or change shape with temperature. Tomorrow’s mechanics will be clean, lean, and increasingly alive.

What’s next? Machines that repair themselves. Robots that adapt like animals. Mechanical systems that grow, evolve, or respond to emotion. Mechanics is going from rigid to flexible, from dumb to brilliant.

It’s not just about force and motion anymore—it’s about machines that understand the world they move through.

10. The Rise of Self-Repairing Machines

Imagine a machine that breaks—and fixes itself. No service call. No human hands. Just built-in awareness, diagnostics, and a mechanical immune system.

That’s not sci-fi anymore. It’s happening right now in the world’s most advanced labs.

Researchers in fields like soft robotics, materials science, and autonomous systems are pushing the boundaries of what machines can do when things go wrong—and how they can bounce back. The goal: machines that can detect damage, isolate the problem, and heal or rebuild the damaged part on their own.

How It Works

Self-repair in machines works across three main fronts:

- Smart Materials

Some materials can heal like skin. Polymers infused with microcapsules can release healing agents when cracked. Others use temperature triggers to “reflow” damage, restoring structural integrity after impact or stress. - Modular Design

Think Lego-style robots. If one piece breaks or malfunctions, the system can eject the bad part and reconfigure itself using backup components or modular redundancy. DARPA-funded robots already do this in simulated disaster zones. - Embedded Sensors + AI Diagnostics

A robot arm today might have hundreds of pressure and strain sensors. AI systems analyze this data in real time, spotting wear or damage before failure. Add predictive modeling, and the machine can act before things go wrong—rerouting power, shifting load, or triggering internal repairs.

Real-World Examples

- Self-Healing Drones

Engineers at the University of Bristol developed a drone that repairs its own wings mid-flight using a rapid-hardening gel. It can suffer serious impact—and keep flying. - Biohybrid Robots

Researchers are experimenting with robots that integrate living tissue, which can grow and self-repair. These “living machines” could one day be used in medical implants or exploration in extreme environments. - Spacecraft with Mechanical Immune Systems

NASA and ESA are studying self-repair systems for long-duration missions, where maintenance isn’t an option. Future spacecraft could use swarming microbots or shape-memory alloys to seal cracks, restore sensors, or rewire power systems on the fly.

Why It Matters

Self-repairing machines are more than just cool—they’re essential.

- In space, there’s no pit stop on Mars.

- In disaster zones, robots must survive debris, collapse, and extreme conditions.

- In deep-sea or nuclear environments, humans can’t intervene at all.

Even consumer tech could benefit: cars that adapt to road damage, wear-resistant smartphones, or bridges that detect and seal microfractures in their structure.

The age of reactive maintenance is fading. We’re heading toward a world where machines will care for themselves, anticipate failure, and evolve toward biological resilience.

Mechanics started with levers and force. Now it’s building machines that survive—and thrive—on their own.

11. Conclusion – Mechanics as Human Heritage and Scientific Bedrock

Mechanics is more than a set of formulas in a physics textbook. It’s the invisible structure behind every working thing we build, wear, drive, launch, or hold in our hands. It’s what lifts our bridges, spins our turbines, keeps satellites in orbit, and gets your coffee poured in the morning.

From the lever to the space probe, mechanics has been with us every step of the way.

It’s also one of the great human legacies. Thousands of years ago, builders figured out how to lift stone and store energy. Inventors created clocks, presses, and pistons long before computers entered the picture. Mechanics is what took us from muscle to machine, from ground to sky, from idea to execution.

And now, it’s going further.

The next generation of mechanical systems won’t just move—they’ll sense, adapt, and evolve. Whether we’re talking about surgical robots, smart infrastructure, autonomous exploration vehicles, or nano-devices swimming through the bloodstream, mechanics will still be at the core. Smarter machines still need gears that spin true, joints that hold firm, forces that balance.

For students, engineers, inventors, or just the endlessly curious, learning the principles of mechanics isn’t just about understanding machines—it’s about understanding the rules that govern the physical world. Once you get them, you start seeing structure and elegance everywhere—from a skateboard trick to a rocket launch.

Mechanics doesn’t just power our world. It shows us how everything fits together.