Table of Contents

- Introduction – Why We Move

The human impulse to travel and how transportation drives civilization. - The Dawn of Transportation – Walking, Wheels, and Beasts

From bipedal migration to the invention of the wheel and the domestication of animals. - Waterways and Ancient Maritime Travel

Early boats, river civilizations, and the rise of seafaring empires. - Roads, Empires, and Infrastructure

How ancient roads enabled commerce, control, and cultural exchange. - The Age of Wind and Sail

The science of navigation, sailing ships, and global exploration. - Steam and Steel – The Industrial Transport Revolution

Railways, steamships, and the transformation of cities and industries. - The Internal Combustion Era – Cars, Trucks, and Highways

The rise of automotive culture and the building of the modern world. - Flight – The Conquest of the Sky

From balloons and biplanes to jets, air travel, and aerospace engineering. - Into the Cosmos – Space Travel and Beyond

The rocket age, satellites, and humanity’s first steps beyond Earth. - Smart Mobility – The Digital and Electric Revolution

Electric vehicles, autonomous systems, and intelligent transport networks. - The Future of Transport – Green, Smart, and Interplanetary

Sustainability, space colonization, and ethical mobility in the 21st century and beyond. - Conclusion – The Journey of Civilization

Reflecting on how transportation shapes our past, present, and shared future.

1. Introduction – Why We Move

From the first human footsteps across African savannahs to the silent glide of spacecraft through the void, transportation has defined our species. It is not just how we move—it is why we move. We travel to survive, to trade, to explore, to build, to connect. Across every era, the science of transportation has shaped civilization itself.

Long before wheels or sails, human legs carried stories, tools, and kin across vast distances. As we learned to tame animals, harness natural forces, and eventually invent engines, our reach expanded dramatically—from continent to continent, across oceans, and into the sky. With each innovation, the science of movement grew more complex: understanding terrain, materials, propulsion, and control systems. Transportation evolved from mere locomotion to an intricate blend of engineering, physics, logistics, and design.

Today, our world pulses with movement: cargo ships chart digital courses across seas, jets crisscross the skies by the second, and satellites orbit above in choreographed dance. Yet tomorrow’s frontiers lie not just in faster speeds, but in smarter, greener, and more equitable systems of mobility.

This article traces the journey of transportation—from its ancient origins to today’s global networks, and into the bold futures of autonomous vehicles, space travel, and sustainable transit. Along the way, we will see how transportation is more than a means—it is the engine of civilization.

2. The Dawn of Transportation – Walking, Wheels, and Beasts

Before the invention of tools, before the rise of empires, before the written word—there were feet. Human transportation began with walking. Our ancestors migrated out of Africa over 100,000 years ago, traversing deserts, mountains, and tundras not by machines, but by sheer will and endurance. These early journeys laid the biological and cultural foundations for everything that would follow.

Foot Travel and Human Migration

Bipedalism—walking on two legs—was one of the defining traits of hominins. It allowed humans to conserve energy, carry tools and children, and survey the landscape. With each generation, people moved farther, eventually spreading across every continent except Antarctica. The earliest roads were simply well-trodden footpaths.

The Domestication of Animals

The next major leap came when humans began domesticating animals. Around 4000–3000 BCE, horses were trained for riding and pulling loads; in other regions, donkeys, camels, and oxen became essential transport partners. These animals extended the reach of early humans, allowing the movement of goods and people across greater distances, especially through deserts, steppes, and mountain passes.

Camels revolutionized trade across the Sahara and Silk Road. In the Americas, llamas served a similar role for the Inca. Animal-powered transport remained the backbone of societies for millennia—and in some remote areas, still does today.

The Invention of the Wheel

One of the most revolutionary inventions in human history, the wheel, emerged around 3500 BCE in Mesopotamia. At first used for pottery, the concept soon transformed land transport when attached to carts and wagons. These early wheeled vehicles required roadways and axles, prompting new kinds of infrastructure and engineering.

The combination of wheel, axle, and draft animal represented a complex mechanical system—an early example of applied physics and design thinking in everyday life. As technology improved, wheels became lighter, stronger, and more efficient. In time, wheeled transport supported commerce, warfare, and governance across civilizations.

3. Waterways and Ancient Maritime Travel

Long before there were roads or railways, rivers and seas served as the world’s highways. Water travel allowed early humans to cross vast distances with greater ease than overland travel, particularly in dense forests, rugged terrain, or arid regions. The science of buoyancy, current navigation, and hull design began not in laboratories but in the slow evolution of boats built from bark, reeds, and dugout logs.

The Earliest Boats and Rafts

Archaeological evidence suggests humans have been building boats for at least 10,000 years. Simple rafts and dugout canoes—some carved from single tree trunks—allowed for fishing, migration, and transport. The oldest known boat, the Pesse canoe from the Netherlands, dates to around 8000 BCE.

Across the world, ingenious adaptations emerged. The people of the Pacific crafted double-hulled canoes and outrigger boats, enabling long-distance island-hopping that colonized thousands of remote islands across Oceania. River civilizations such as those along the Nile, Indus, and Yangtze developed specialized boats suited to their local currents and cargo needs.

The Rise of Seafaring Civilizations

As societies grew and trade expanded, so did maritime ambition. The Egyptians mastered river navigation; the Phoenicians became master shipbuilders and navigators of the Mediterranean; the Greeks and Romans developed galleys for war and commerce. The Chinese constructed large river and sea vessels, and Polynesian navigators—without compasses—used the stars, wind, and waves to chart ocean routes thousands of kilometers long.

This age saw the birth of many nautical sciences: wind propulsion using sails, hydrodynamics in hull design, and early celestial navigation. Naval architecture became a respected and empirical art form.

Maritime Trade and Expansion

Ships enabled the exchange of goods, ideas, technologies, and even religions across continents. From spice routes to Viking raids, from Chinese junks to Arab dhows, maritime transport reshaped the world’s cultural and economic landscape.

The tools and techniques developed during this era laid the groundwork for the great voyages of the Age of Exploration—and for the shipping networks that still power the global economy today.

Here is the draft for:

4. Roads, Empires, and Infrastructure

As civilizations grew more complex, the need for reliable overland transport systems became increasingly vital. Roads were no longer mere dirt tracks—they became strategic instruments of empire, tools of commerce, and expressions of technological and political power. The science of surveying, grading, paving, and maintaining road networks evolved alongside the empires that built them.

The Engineering of Ancient Roads

Some of the earliest planned road systems appeared in Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley, but it was the Roman Empire that perfected the art. Roman roads—over 400,000 kilometers at their height—were marvels of engineering: layered with stone, gravel, and sand, and designed for durability and drainage. Many still exist today, buried beneath or running parallel to modern roads.

Roman surveyors used tools like the groma and chorobates to measure straight lines and gradients. Roads often followed military logic, connecting forts, borders, and capitals in the most direct paths possible. The expression “all roads lead to Rome” wasn’t just rhetorical—it was an engineered reality.

The Incan and Persian Road Networks

Other civilizations also created stunning infrastructure. The Inca built thousands of kilometers of roads through the Andes, using staircases, rope bridges, and tamped-earth paths. Their runners (chasquis) used relay systems to transmit messages rapidly. The Achaemenid Persians developed the Royal Road, a precursor to modern postal and logistics systems.

In each case, the roads reflected the needs of the state—commerce, control, communication—and required systematic knowledge of geography, geology, and construction.

Wheeled Transport and Road Vehicles

As roads improved, so too did the vehicles that used them. Carts, wagons, and chariots—sometimes with suspension systems or iron-rimmed wheels—allowed goods and people to move faster and more safely. Innovations in axle design, weight distribution, and harnessing systems contributed to the early science of land transport mechanics.

These networks also facilitated cultural and technological diffusion, allowing everything from language and law to metalwork and music to travel across regions. Roads made empires—but they also made globalization possible, centuries before the term existed.

5. The Age of Wind and Sail

With the refinement of sails, shipbuilding, and navigation tools, humanity entered a new era of maritime mobility. The Age of Wind and Sail—spanning roughly from the 15th to the early 19th century—redefined global transportation, ushering in a time of exploration, conquest, trade, and scientific discovery. This period marked the emergence of transportation not only as a tool of movement but as a defining force of geopolitics, economy, and empire.

The Power of the Wind

Harnessing the wind allowed ships to travel farther and faster than ever before. Innovations in sail design—such as the triangular lateen sail—made vessels more maneuverable and capable of tacking against the wind. Square sails provided power on open seas, while multiple-mast rigs enabled complex wind management.

These developments weren’t guesswork—they required a practical understanding of aerodynamics, rigging tensions, and center-of-gravity balance, refined over centuries by shipbuilders and sailors through trial, error, and innovation.

Navigation Becomes a Science

Exploration required not only strong ships but the ability to chart a reliable course. The invention and widespread use of the magnetic compass, astrolabe, and later the sextant transformed navigation from a mystical art into an empirical science.

Cartography advanced rapidly. Maps improved in accuracy, and the field of celestial navigation—using stars, the sun, and horizon angles—allowed for long-distance open-ocean voyages. The development of marine chronometers in the 18th century solved the longstanding problem of determining longitude.

Age of Exploration and Global Maritime Trade

Driven by a thirst for spice, gold, and territory, European powers launched expeditions around the world. The Portuguese and Spanish pioneered oceanic routes to Asia, Africa, and the Americas. The Dutch and British soon followed, building vast colonial and commercial networks supported by powerful navies and merchant fleets.

Ships like the caravel, carrack, and galleon carried goods, weapons, people—and sometimes devastating diseases—across oceans. The world was becoming smaller, connected by ships propelled by wind and guided by the stars.

Clippers, Convoys, and Naval Power

By the 18th and 19th centuries, commercial shipping reached a high point with the creation of clipper ships—sleek, fast vessels designed to maximize wind efficiency and cargo speed. Meanwhile, naval warfare drove advances in hull design, firepower, and sailing strategy.

Sailing became more than a means of movement—it became a science in itself, uniting engineering, meteorology, astronomy, and cartography. It set the stage for the next great revolution in transportation: steam.

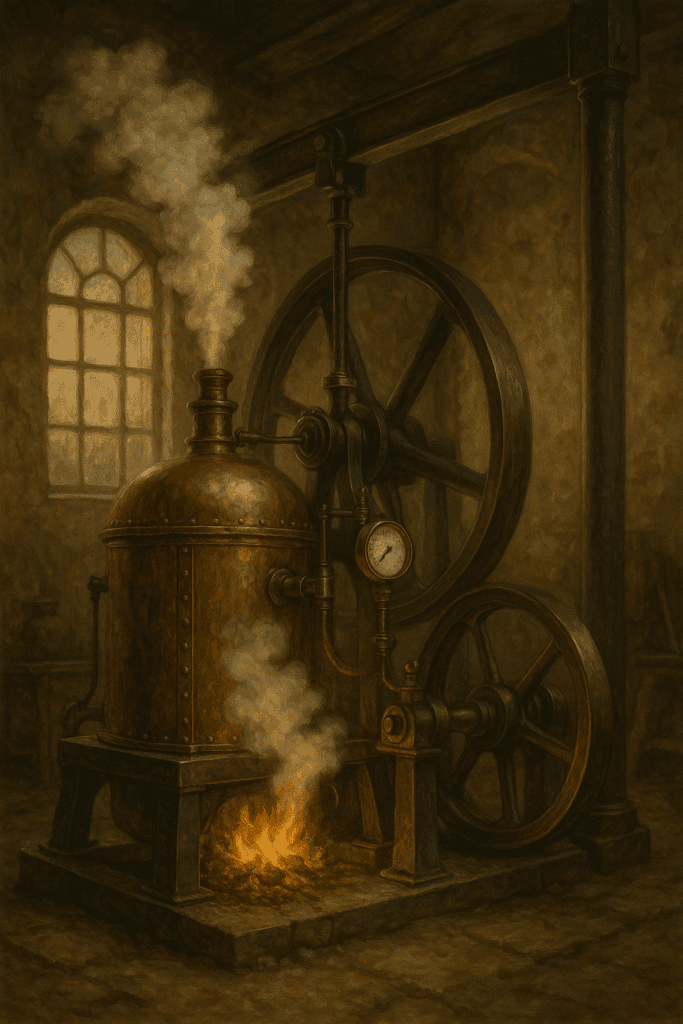

6. Steam and Steel – The Industrial Transport Revolution

The 19th century witnessed a transportation revolution driven by two powerful forces: steam power and steel engineering. This era fundamentally transformed how goods, people, and ideas moved across the planet. It was the first time in history that transportation could be truly mechanized, scheduled, and scaled—liberating mobility from the whims of wind, muscle, and terrain.

The Rise of the Steam Engine

Although steam technology had early prototypes dating back to antiquity, it was not until the late 18th century that engineers like James Watt made the steam engine efficient and practical. Its impact was swift and far-reaching.

Steam engines powered trains, steamboats, and eventually steamships, inaugurating a new era of mass transportation. They turned rivers and railways into superhighways of the industrial age. For the first time, people and cargo could travel long distances at speeds previously unimaginable.

Railroads and the New Geography

Railways rapidly spread across Europe, North America, and later Asia and Africa. Early British lines like the Stockton and Darlington Railway (1825) and the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (1830) became blueprints for a global rail boom. Trains connected cities to countrysides, mines to markets, and nations to each other.

The science of railways included metallurgy, civil engineering, and mechanical design: laying track beds, building trestles and tunnels, designing locomotives and brakes. Rail schedules also demanded synchronized timekeeping, helping standardize time zones.

In the U.S., the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 symbolized this transformation, linking Atlantic and Pacific and opening vast territories to migration, trade, and industry.

Steamboats and Ocean Steamers

Steamships redefined maritime transport. The first successful steamboats—like Robert Fulton’s Clermont (1807)—proved that rivers could be navigated upstream and reliably. Steamships soon replaced sailing ships for inland and coastal transport.

Ocean-going steamships, powered by coal-fired engines, began to cross the Atlantic and Pacific. By the late 19th century, companies like Cunard and White Star Line were running regular passenger and cargo routes between continents.

Infrastructure and Urban Transformation

To support this new wave of mobility, massive infrastructure projects emerged: bridges, canals, tunnels, and ports. Engineering triumphs like the Panama Canal, Brooklyn Bridge, and Gotthard Tunnel became symbols of industrial prowess.

Cities grew around rail stations and docks. Urban planning adapted to accommodate tramways and underground rail (such as the London Underground, the world’s first metro, opened in 1863).

This era marked the fusion of engineering, physics, and commerce in transportation—laying the groundwork for the internal combustion engine and the coming automotive age.

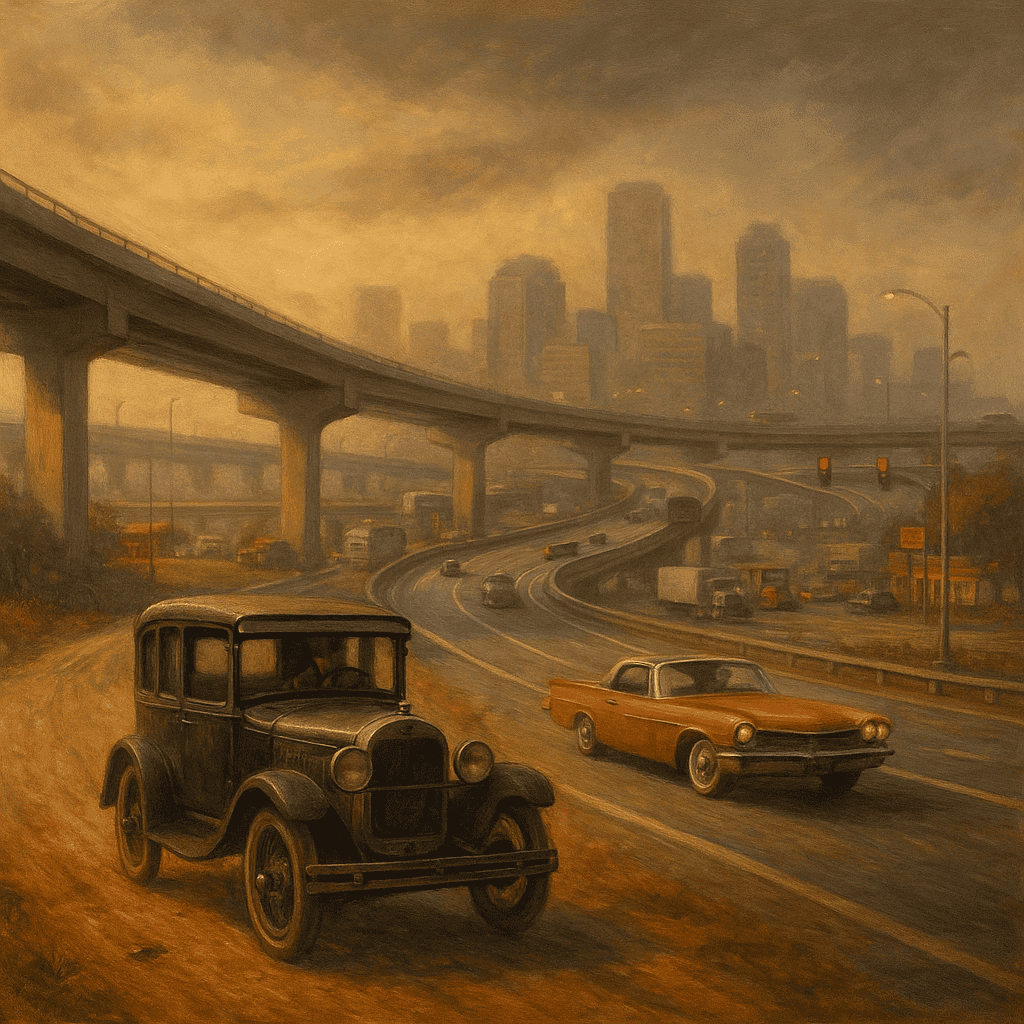

7. The Internal Combustion Era – Cars, Trucks, and Highways

If steam opened the door to mass transportation, the internal combustion engine flung it wide open. Compact, powerful, and efficient, this new technology made personal mobility possible and reshaped the 20th-century world—physically, economically, and culturally. Cars, trucks, buses, and motorcycles became defining symbols of modern life, while roads and highways redefined the geography of nations.

The Birth of the Automobile

The late 19th century saw rapid experimentation with motorized vehicles. Early models by Karl Benz (1885) and Gottlieb Daimler were soon followed by innovations across Europe and America. By 1908, Henry Ford’s Model T—produced using the revolutionary moving assembly line—made cars affordable to the masses.

Internal combustion engines, typically powered by gasoline or diesel, offered advantages over steam: quicker startup, greater range, and more compact size. The science behind them included thermodynamics, fluid mechanics, materials engineering, and combustion chemistry.

Trucks, Buses, and the Rise of Road Transport

Automotive transport extended beyond private cars. Trucks revolutionized freight logistics, replacing horses and wagons with speed and capacity. Buses enabled mass public transit in growing cities. Tractors and other vehicles mechanized agriculture, further transforming society.

Governments responded by building road networks. The U.S. Interstate Highway System (initiated in the 1950s), the Autobahn in Germany, and road expansions across Europe, Asia, and Latin America created arteries of commerce and culture. Roads no longer just connected cities—they carved them into being.

Car Culture and the Modern World

The automobile did more than move people—it moved societies. It influenced urban sprawl, created suburbs, and birthed new industries: oil, rubber, insurance, roadside services, and car manufacturing giants. It became embedded in music, fashion, film, and national identity—from Route 66 to Autobahn thrills.

At the same time, automotive transport brought new challenges: air pollution, traffic accidents, and oil dependency. These prompted advances in traffic engineering, automotive safety, and environmental science, from catalytic converters to seatbelts to emissions standards.

Engineering the Highways

The construction of modern highways required sophisticated civil engineering: grading land, designing curves and slopes for safety, building bridges and tunnels, and managing water runoff. Traffic systems—signals, signage, interchanges—emerged as a science of control and flow.

This era wasn’t just about speed—it was about reshaping time, space, and human life. And yet, as cars conquered the land, humans were already dreaming of the sky.

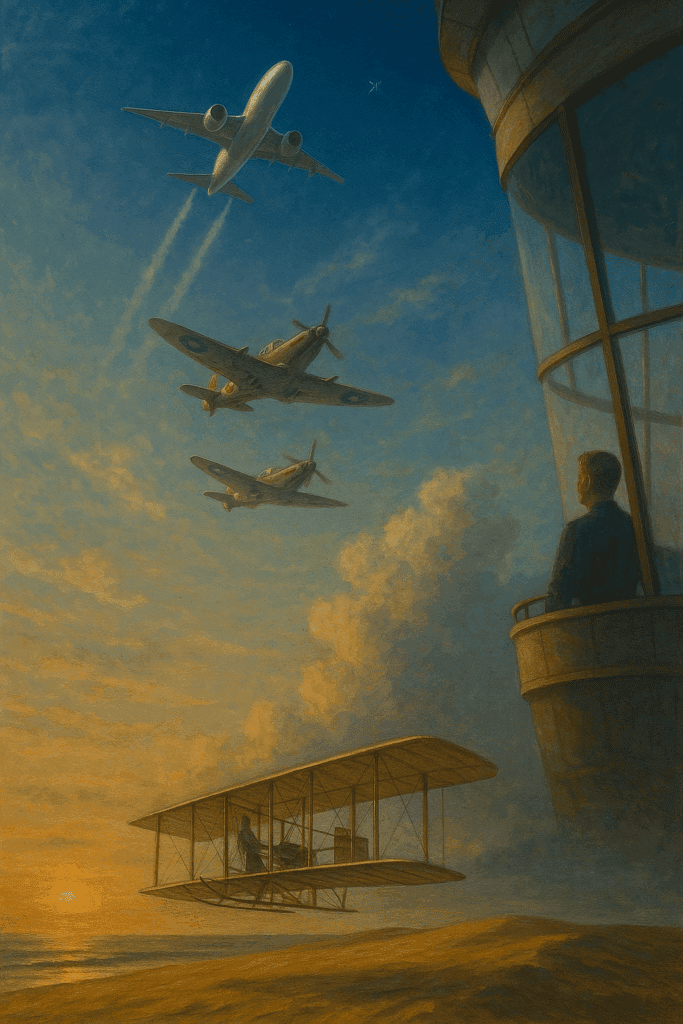

8. Flight – The Conquest of the Sky

For millennia, the sky was the realm of myth and dream—home to gods, dragons, and angels. But in the 20th century, humanity broke free from the ground and took flight. Powered aviation transformed the world with breathtaking speed, turning oceans into mere hours and bringing even the most distant places within reach. The science of flight—aerodynamics, propulsion, navigation, and materials—ushered in an era of unprecedented mobility.

From Balloons to Wings

The first manned flight didn’t involve engines, but hot air. In 1783, the Montgolfier brothers launched a hot-air balloon carrying passengers over Paris. Soon after, gas-filled balloons and dirigibles (airships) like the Zeppelin would float across skies, though limited by weather and fragility.

The real breakthrough came in 1903, when Orville and Wilbur Wright achieved the first powered, controlled flight in North Carolina. Their Flyer, built from wood and fabric, demonstrated that sustained flight was possible with engine propulsion and proper aerodynamic design.

The Science of Aeronautics

Flight is a triumph of applied physics. Four forces—lift, drag, thrust, and weight—govern every aircraft’s performance. The wings (airfoils) must generate lift; engines must provide thrust; drag must be minimized; weight must be managed. Materials science, wind tunnel testing, and fluid dynamics became essential to the design of planes.

As engines improved—from piston to jet propulsion—so did the range and speed of aircraft. By mid-century, jets like the Boeing 707 and Concorde could cross continents and oceans in hours.

Military Aviation and Aerospace Research

Wartime drove innovation. During World Wars I and II, airplanes evolved rapidly: from fabric biplanes to all-metal fighters and bombers. Radar, pressurized cabins, and turbojet engines emerged. The Cold War intensified aerospace research, eventually blending with the space race.

Organizations like NASA, Boeing, and Lockheed developed cutting-edge technology with crossover into civilian air travel. Military aircraft, drones, and stealth technologies also emerged, pushing flight into new dimensions of speed and capability.

Commercial Aviation and the Jet Age

After World War II, flying became accessible to the public. The “Jet Age” of the 1950s and ’60s brought commercial aircraft that redefined tourism, migration, and business. Airports became global gateways. Air traffic control evolved into a complex logistical science involving radar, weather modeling, satellite positioning, and increasingly, artificial intelligence.

Air travel reshaped global economics, shrank distances, and rewrote geopolitics. It also introduced new concerns: noise pollution, fossil fuel emissions, and aviation safety—prompting ongoing innovation in greener fuels, electric aircraft, and noise reduction technologies.

Today, aviation is not just about getting from A to B—it’s about engineering precision, global coordination, and the human dream to fly.

9. Into the Cosmos – Space Travel and Beyond

The conquest of the skies was only the beginning. In the mid-20th century, transportation made its boldest leap yet—beyond Earth itself. Space travel redefined the very limits of mobility, fusing the sciences of aeronautics, physics, chemistry, materials science, robotics, and astronomy into one of humanity’s most extraordinary achievements. For the first time, we were not just visitors of the Earth—we became voyagers of the cosmos.

The Rocket Age Begins

Theoretical groundwork for rocketry dates back to thinkers like Konstantin Tsiolkovsky and Robert Goddard, but it was during and after World War II that functional rocketry advanced dramatically. German V-2 missiles were the first human-made objects to reach the edge of space.

In 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1, the world’s first artificial satellite. Just four years later, Yuri Gagarin became the first human in orbit. The space race between the USSR and the USA turned spaceflight into a matter of global prestige and national security.

The Moon Landing and Human Spaceflight

On July 20, 1969, the Apollo 11 mission landed humans on the Moon—an event widely regarded as the pinnacle of 20th-century technology. Neil Armstrong’s words—“That’s one small step for man…”—echoed the enormous leap for science, engineering, and human aspiration.

Human spaceflight required solving problems in zero gravity, life support, trajectory physics, orbital mechanics, and spacecraft materials. It also pushed advances in computing, telemetry, and miniaturization.

Satellites, Robotics, and Space Science

Most space travel today is robotic. Satellites have become the invisible infrastructure of modern life, enabling GPS, weather forecasting, communications, remote sensing, and global internet services. Robotic probes like Voyager, Curiosity, and James Webb have extended our reach across the solar system and beyond.

Space transport also includes science fiction–turned–reality technologies like space stations, reusable launch systems, and autonomous docking. The International Space Station (ISS), orbiting Earth since 1998, is a symbol of global scientific cooperation.

The New Space Economy

Private companies have reenergized space transport. Firms like SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Virgin Galactic are launching satellites, delivering cargo, and even preparing for space tourism. The Falcon 9 and Starship series have introduced reusable rocket stages, drastically lowering costs and expanding access to orbit.

Meanwhile, international agencies plan manned missions to Mars, construction of lunar bases, and exploration of asteroids. Concepts like space elevators, nuclear propulsion, and terraforming are under serious scientific study.

Why Space Matters for Transportation

Space travel is not just about exploration—it is the ultimate testbed for transport science. It demands maximum efficiency, safety, autonomy, and innovation. From Earth orbit to interplanetary transit, space redefines what it means to move, to survive, and to think beyond our current limitations.

We now stand at the edge of a new era—where transportation doesn’t just cross borders, but planets.

10. Smart Mobility – The Digital and Electric Revolution

The 21st century has brought a wave of innovation in transportation driven not just by engines and steel, but by data, software, and sustainability. This new era—characterized by electric vehicles, digital logistics, and intelligent automation—marks a dramatic shift in how we think about mobility: not simply as movement, but as a service, a network, and a planetary responsibility.

The Rise of Electric Vehicles (EVs)

Electric transportation is not new—the first EVs date back to the 19th century—but modern advances in battery technology, power electronics, and materials have transformed their potential. Companies like Tesla, BYD, Rivian, and many legacy automakers now produce EVs that compete with or outperform combustion vehicles in speed, range, and efficiency.

Breakthroughs in lithium-ion batteries, regenerative braking, and charging infrastructure have made EVs viable for mass adoption. EVs also produce no tailpipe emissions, making them a cornerstone of climate-conscious transport.

Autonomous Vehicles and Artificial Intelligence

Perhaps the most radical transformation lies in removing the human driver. Self-driving cars, delivery bots, and autonomous drones use a combination of LIDAR, radar, GPS, cameras, and AI algorithms to sense and navigate environments.

Companies like Waymo, Cruise, and Baidu Apollo are testing fully driverless vehicles. Autonomous transport raises deep questions—not just technical, but ethical: How should a machine make split-second moral decisions? Who is responsible for an accident?

The science of autonomy blends robotics, machine learning, control theory, and human-computer interaction. It may reshape cities, eliminate traffic deaths, and redefine personal mobility.

Mobility as a Service (MaaS)

Digital platforms like Uber, Grab, Bolt, and Lyft introduced the idea of transportation on demand. Today, entire ecosystems integrate ride-sharing, scooters, car rentals, bikes, and public transport into unified apps.

The science of MaaS includes data science, user experience design, dynamic pricing, and real-time routing algorithms. These systems optimize urban transport flows and reduce car ownership, especially in dense cities.

High-Speed and Smart Rail Systems

Countries like Japan, France, and China lead in high-speed rail (HSR), using advanced train aerodynamics, magnetic levitation (Maglev), and automated controls. Proposals like the Hyperloop, using vacuum tubes and magnetic propulsion, aim to cut long-distance travel times dramatically.

Smart rail integrates sensor networks, predictive maintenance, automated scheduling, and clean energy systems. It represents an efficient and scalable solution for intercity and regional travel.

The Electrified Logistics Chain

Logistics—the science of moving goods—has also gone digital. Smart warehouses, autonomous forklifts, electric trucks, and drones are transforming supply chains. GPS tracking, blockchain, and AI optimize delivery routes and inventory management.

Companies like Amazon, DHL, and Maersk are investing heavily in green logistics, carbon-neutral shipping, and even electric cargo ships.

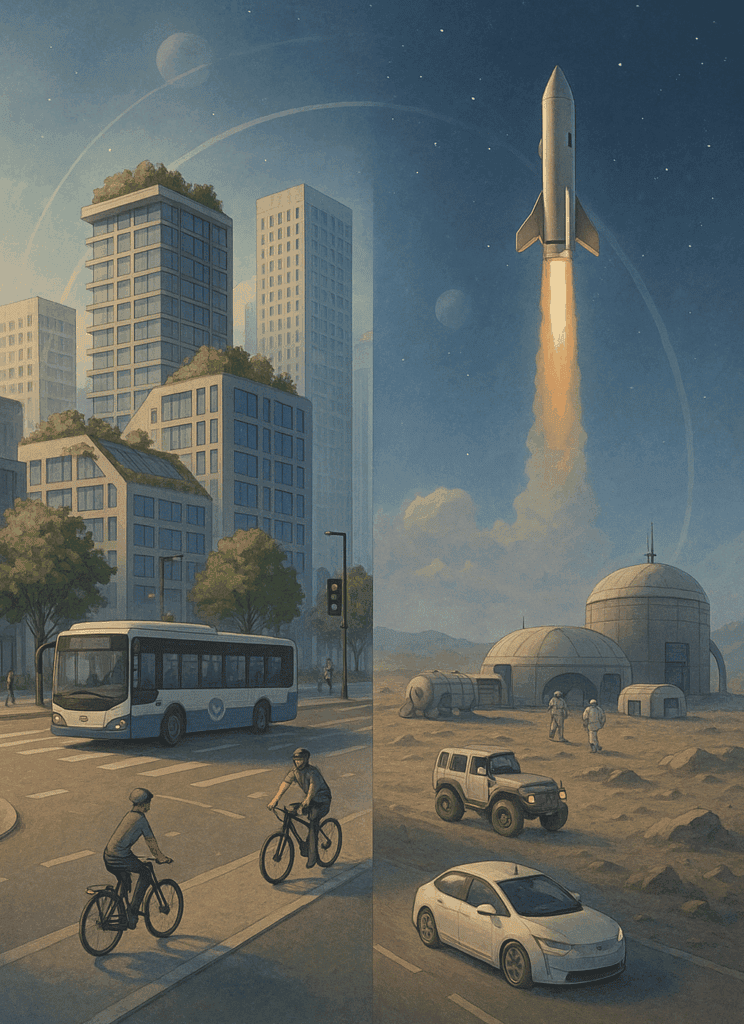

11. The Future of Transport – Green, Smart, and Interplanetary

As we look to the horizon, the future of transportation is defined by three imperatives: sustainability, intelligence, and expansion beyond Earth. The systems we build now will determine how well we connect human beings and ideas—without destroying the environment we depend on. The transportation of the future must be not only faster and smarter but cleaner, fairer, and cosmic in ambition.

Sustainable Transport and Green Energy

Climate change and resource depletion have made it clear: the internal combustion engine’s century-long reign must give way to carbon-neutral transport. The transition is already underway.

- Electric and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles promise zero-emission alternatives.

- Biofuels and synthetic fuels are being tested for aviation and shipping.

- Urban planners are emphasizing walkable cities, cycling infrastructure, and mass transit systems powered by renewable energy.

This transition demands breakthroughs in battery chemistry, fuel storage, renewable energy integration, and vehicle lifecycle sustainability.

Smart Cities and Integrated Mobility

In the future, transportation won’t be isolated—it will be embedded in the fabric of intelligent urban systems. Smart cities use sensors, data, and AI to optimize traffic flow, reduce emissions, and make public transport seamless.

Imagine a world where:

- Your phone syncs with public transit, rideshare, or e-bike options in real time.

- AI models predict congestion and reroute traffic before it happens.

- Dynamic pricing and incentives reduce wasteful commutes.

Cities like Singapore, Helsinki, and Seoul are already pioneering such systems, guided by the science of systems engineering, urban design, and mobility analytics.

New Forms of Human Movement

Tomorrow’s transport may not even look like today’s.

- Exoskeletons and personal air vehicles could give new dimensions to individual mobility.

- Hyperloop systems might transport passengers in vacuum tubes at airplane speeds.

- Quantum levitation, materials science, and electromagnetic propulsion may enable innovations we haven’t yet imagined.

Interplanetary Transit and Space Habitats

Humanity is now seriously preparing for interplanetary life. Mars missions, Moon bases, and asteroid mining require vehicles capable of deep space propulsion, radiation shielding, and closed-loop life support. Future transportation will include:

- Space elevators or launch loops

- Ion drives and nuclear propulsion systems

- Modular spacecraft with self-repairing components

- In-situ resource utilization (ISRU)—fuel and parts made on other worlds

These projects push the boundaries of transportation science, merging aerospace engineering, astrophysics, artificial intelligence, and bioengineering.

Ethical and Global Considerations

The transportation of the future must be not only technological but ethical:

- Who gets access to new modes of movement?

- Will AI-driven transport be fair and safe?

- How can we ensure mobility justice for underserved communities and developing nations?

Transportation, at its best, is freedom—the freedom to connect, to grow, to imagine. It must evolve not only in speed and sophistication but in humanity.