Table of Contents

- Introduction – What Is Musicology?

The interdisciplinary study of music as art, science, and human experience. - A Journey Through Music History

- A. Major Periods and Styles

From ancient chants to contemporary experimental forms. - B. Global Musical Traditions

The diverse sound worlds of cultures across the globe.

- A. Major Periods and Styles

- The Evolution of Music Technology

How tools—from bone flutes to AI—have shaped the music we create and hear. - Contemporary Research at Cambridge University

Cutting-edge studies in cognition, performance, psychology, and music education. - Conclusion – The Future of Musicology

Rethinking music in an age of data, diversity, and digital possibility.

I. Introduction – What Is Musicology?

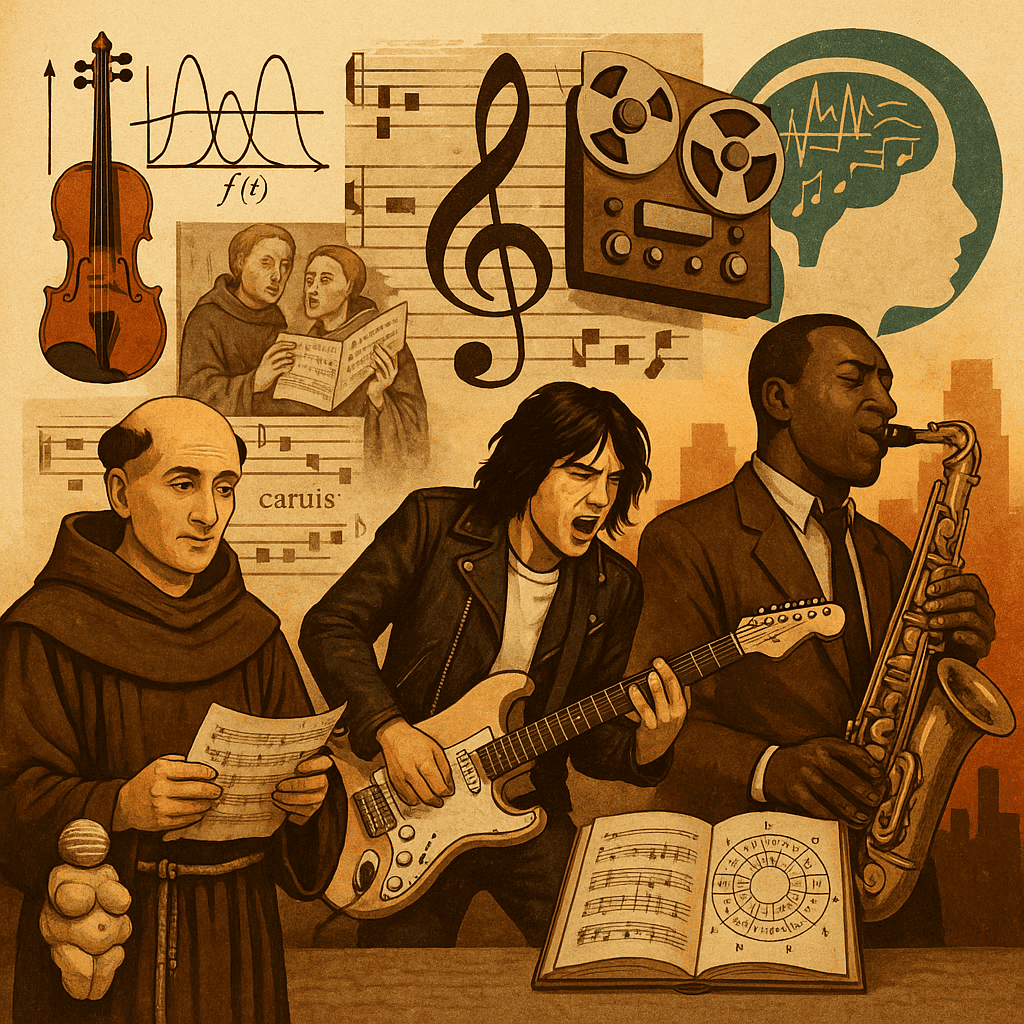

Music is one of the most universal human experiences—ancient and ever-evolving, profoundly emotional and mathematically precise. But behind the beauty of a song or the power of a symphony lies a complex web of ideas, traditions, technologies, and psychological responses. Understanding this complexity is the work of musicology, the scientific and scholarly study of music.

Musicology is not just one field—it is many, interwoven. It includes historians who trace the evolution of musical styles across centuries and cultures; theorists who dissect harmonic structures and compositional techniques; ethnomusicologists who immerse themselves in the musical worlds of different societies; and psychologists and neuroscientists who explore how music moves us, heals us, and shapes our cognition.

At its core, musicology asks questions such as:

- How do different cultures express meaning through music?

- What is the structure of a fugue, a sonata, a jazz solo?

- How does the brain process rhythm, melody, and harmony?

- What role does music play in identity, memory, and emotion?

- How has technology—from the printing press to artificial intelligence—transformed the way music is made, shared, and experienced?

Musicology spans the arts and sciences, drawing from philosophy, anthropology, history, physics, computer science, education, and medicine. It connects the subjective (how music makes us feel) with the objective (how sound behaves), and the cultural (how music expresses social values) with the personal (how music reflects and shapes who we are).

Whether analyzing a medieval chant, investigating how toddlers respond to lullabies, or programming neural networks to generate musical compositions, musicologists help us understand music not only as an art—but also as a science.

In this article, we’ll explore the major themes and discoveries in the field of musicology:

- the grand arc of music history across continents and styles,

- the revolutionary impact of music technologies,

- and the cutting-edge research taking place at institutions like the University of Cambridge.

Through this lens, we can appreciate music not just as a soundtrack to our lives—but as a deep and dynamic field of human inquiry.

II. A Journey Through Music History

A. Major Periods and Styles

The history of music is the story of human civilization in sound. Across cultures and centuries, music has served as ritual, celebration, protest, prayer, entertainment, and art. In the Western tradition, music history is often divided into major stylistic periods, each shaped by social change, innovation, and evolving aesthetics. While this outline focuses on European music history for clarity, it sets the stage for exploring global traditions in the next section.

1. Antiquity (Before 500 CE)

Music predates written history. The oldest known musical instruments—bone flutes and drums—date back over 40,000 years. In ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, India, China, and Greece, music was central to religious life, royal ceremony, healing rituals, and daily labor.

- Greek philosophers such as Pythagoras and Aristotle linked music to cosmic harmony and mathematical proportions, an idea that would influence music theory for centuries.

- Ancient instruments included the lyre, aulos, sistrum, and lute.

- Musical notation was rudimentary or absent; music was passed down orally.

Though little survives of the actual sounds, we know that music was deeply symbolic, often tied to the divine, the natural world, and the rhythm of human life.

2. Medieval Period (500–1400)

After the fall of Rome, music in Europe became closely aligned with the Christian Church.

- Gregorian chant, a style of plainchant, became the dominant liturgical form—monophonic, meditative, and sung in Latin.

- By the 9th century, early polyphony began to emerge, where two or more vocal lines were sung simultaneously.

- Innovations like neumatic notation and later staff-based notation allowed music to be preserved and studied more systematically.

- Secular music was also alive in the form of troubadour songs, dance tunes, and folk traditions.

This era laid the theoretical and liturgical foundations for later Western music, and monastic institutions became key centers of musical transmission.

3. Renaissance (1400–1600)

The Renaissance—meaning “rebirth”—ushered in a flourishing of human creativity and inquiry, including music.

- Composers like Josquin des Prez, Palestrina, and William Byrd elevated polyphonic choral music to intricate and expressive heights.

- Music became more text-driven, emphasizing clarity and emotion.

- Music printing (first by Ottaviano Petrucci in 1501) revolutionized dissemination, making sheet music more widely available.

- The rise of secular forms like the madrigal and the consort song reflected a growing appetite for music outside the church.

Renaissance music often feels spacious and balanced, rich in vocal harmony, and shaped by new philosophical ideals of beauty, proportion, and reason.

4. Baroque Period (1600–1750)

The Baroque era was marked by drama, complexity, and grandeur. Music expanded in scale, emotional range, and technical sophistication.

- Composers such as J.S. Bach, George Frideric Handel, Antonio Vivaldi, and Claudio Monteverdi flourished.

- New genres emerged: opera, concerto, oratorio, and fugue.

- Instrumental music grew in stature, with developments in keyboard, string, and orchestral writing.

- The basso continuo—a form of continuous bass accompaniment—became a hallmark.

Baroque music emphasized contrast, motion, and virtuosity, often guided by the Doctrine of Affections, which aimed to evoke specific emotions through musical techniques.

5. Classical Period (1750–1820)

Not to be confused with “classical music” in general, this period focused on structure, symmetry, and refinement.

- Central figures: Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and early Ludwig van Beethoven.

- Formal structures like the sonata form, symphony, and string quartet defined musical architecture.

- Clarity, proportion, and logical development replaced the ornate intensity of the Baroque.

- Music moved from court patronage toward public concerts, reflecting the values of the Enlightenment.

Classical compositions speak with elegance and balance, often exploring human emotion through carefully crafted forms.

6. Romantic Period (1820–1900)

Romantic composers rebelled against Classical restraint, favoring emotion, individuality, and imagination.

- Key figures: Frédéric Chopin, Johannes Brahms, Franz Liszt, Richard Wagner, Tchaikovsky, and late Beethoven.

- Music became more personal and programmatic, telling stories or expressing inner turmoil and national identity.

- Orchestras grew, harmonies expanded, and technical demands increased.

- Nationalist schools emerged (e.g., the Russian Five), drawing on folk traditions to assert cultural identity.

This era gave rise to many of the concert staples we cherish today—music that speaks directly to the heart and explores the full spectrum of human experience.

7. 20th Century to Present

The 20th century exploded with innovation, rebellion, and diversity.

- Modernist movements included atonality (Schoenberg), minimalism (Glass, Reich), impressionism (Debussy), and serialism.

- Popular genres like jazz, blues, rock, hip-hop, electronic, and world music fusion redefined the musical landscape.

- Technology transformed both production and distribution, from radio to the internet to AI composition.

- Contemporary composers like John Adams, Kaija Saariaho, and Tan Dun continue to blend tradition and innovation.

Today’s music world is pluralistic, globalized, and boundary-breaking—bridging traditions, experimenting with form, and reflecting a vast range of human voices and experiences.

II. A Journey Through Music History

B. Global Musical Traditions

While Western classical music often dominates textbooks and concert halls, music has developed independently—and vibrantly—in every part of the world. These global traditions reflect the values, myths, social structures, and spiritual lives of the cultures that created them. Musicology today places strong emphasis on ethnomusicology, which studies music as a cultural phenomenon—listening not just to the sounds, but also to their meanings and roles in society.

Below is a survey of some of the world’s major musical traditions, each worthy of deep study on its own.

1. Indian Classical Music – The Sound of Devotion and Precision

India’s music tradition is one of the oldest and most sophisticated in the world, deeply rooted in spiritual philosophy and refined performance practices.

- Divided into two main systems:

- Hindustani music (North India): Often improvisational, influenced by Persian and Islamic traditions.

- Carnatic music (South India): More composition-based, with a strong emphasis on structure and vocal performance.

- Hindustani music (North India): Often improvisational, influenced by Persian and Islamic traditions.

- Central concepts:

- Raga – melodic framework that guides improvisation and mood.

- Tala – intricate rhythmic cycles played on instruments like the tabla and mridangam.

- Raga – melodic framework that guides improvisation and mood.

- Often associated with religious practice, meditation, and poetry.

- Instruments include the sitar, veena, bansuri (flute), and sarangi.

This tradition emphasizes not just technical mastery but also emotional depth and spiritual transmission.

2. Chinese Classical and Folk Music – Harmony with Nature and Ritual

Chinese music has a recorded history stretching back over 3,000 years and is tightly interwoven with philosophy, Confucian ethics, and cosmology.

- Built around pentatonic scales and subtle expressive ornamentation.

- Key instruments:

- Guzheng (plucked zither), erhu (two-stringed fiddle), dizi (bamboo flute), and pipa (lute).

- Guzheng (plucked zither), erhu (two-stringed fiddle), dizi (bamboo flute), and pipa (lute).

- Types:

- Court music (e.g., during the Tang dynasty).

- Opera (especially Peking Opera).

- Folk traditions tied to regions and ethnic minorities.

- Court music (e.g., during the Tang dynasty).

- Philosophical frameworks (like Daoism and Confucianism) emphasized balance, discipline, and emotional restraint.

Chinese music often mirrors nature—rushing water, falling leaves, or birdsong—conveying emotional nuance without overt sentimentality.

3. Japanese Traditional Music – Precision, Stillness, and Ritual

Japanese music combines elegance with economy, ritual with spontaneity.

- Genres:

- Gagaku – ancient court music, slow and meditative, performed on instruments like the sho (mouth organ) and koto.

- Noh and Kabuki theatre music – tightly integrated with drama and dance.

- Shakuhachi (bamboo flute) music – associated with Zen monks and spiritual practice.

- Gagaku – ancient court music, slow and meditative, performed on instruments like the sho (mouth organ) and koto.

- Characterized by:

- Ma (間) – the aesthetic of space and silence.

- Jo-ha-kyū structure – gradual buildup, development, and rapid conclusion.

- Ma (間) – the aesthetic of space and silence.

Japanese music prioritizes presence, timing, and clarity—mirroring Zen principles of mindfulness and impermanence.

4. African Music Traditions – Polyrhythm, Community, and Ancestral Voice

African music is extraordinarily diverse, with thousands of ethnic groups and musical languages. Yet certain unifying features recur:

- Polyrhythms – simultaneous overlapping rhythms that form complex, dynamic textures.

- Call-and-response – interactive performance between leader and group.

- Percussion-centric – drums like the djembe, talking drum, and udu are central.

- Music is often communal, embedded in ceremonies, storytelling, and healing.

- Instruments: Kora (West African harp), mbira (thumb piano), balafon (xylophone).

Music in many African societies is inseparable from dance, oral history, and spiritual life—it is participatory, not just performative.

5. Middle Eastern Music – Melodic Subtlety and Rhythmic Intricacy

Middle Eastern musical traditions—ranging from Arab maqam to Persian dastgah—reflect centuries of poetic, philosophical, and spiritual thought.

- Built on modal systems:

- Maqam (Arab), Dastgah (Persian), Mugham (Central Asian).

- Maqam (Arab), Dastgah (Persian), Mugham (Central Asian).

- Use of microtones – intervals smaller than in Western tuning systems.

- Rich ornamentation and melisma (fluid movement between notes).

- Instruments: Oud, qanun, ney, santur, darbuka.

Much of this music evolved in courts, mosques, and poetic gatherings, expressing themes of love, longing, and divine beauty.

6. Latin American and Caribbean Traditions – Fusion, Passion, and Resistance

Latin America is home to musical hybridity born from centuries of cultural contact—Indigenous, African, European, and later, global influences.

- Styles include:

- Samba, Bossa Nova, Tango, Mariachi, Son Cubano, Reggaeton, Cumbia, and more.

- Samba, Bossa Nova, Tango, Mariachi, Son Cubano, Reggaeton, Cumbia, and more.

- Features:

- Syncopated rhythms, danceable grooves, and rich vocal traditions.

- Syncopated rhythms, danceable grooves, and rich vocal traditions.

- Instruments: Charango, cuatro, congas, bongos, maracas, accordion.

- Music serves roles in celebration, protest, storytelling, and cultural pride.

Each country offers a unique blend, yet all are united by a deep cultural attachment to rhythm and social storytelling.

7. Indigenous and Tribal Musics Worldwide – Sound as Spirit

Across the globe, Indigenous music connects people to the land, ancestors, and mythic origins.

- Often integrated with rituals, initiation ceremonies, hunting practices, and seasonal cycles.

- Instruments: didgeridoo (Australia), bullroarer, log drum, jaw harp, chant, vocables (non-verbal syllables).

- Music is functional, not separated from daily life.

These traditions are endangered by globalization but also revitalized through preservation efforts, scholarship, and cultural revival.

Conclusion of Section II.B:

Global musical traditions remind us that music is not a single language but a constellation of languages—each with its own grammar, vocabulary, and soul. Ethnomusicology helps us understand these traditions not as exotic curiosities but as vital expressions of human creativity and identity.

III. The Evolution of Music Technology

From Bone Flutes to Artificial Intelligence

Music and technology have always gone hand in hand. From the earliest crafted instruments to today’s digital soundscapes, music has been shaped not only by inspiration and culture but by innovation. Every leap in music technology has altered how musicians compose, how audiences listen, and how societies engage with sound.

This section traces key technological milestones that transformed the music landscape.

A. Early Innovations – Tools of the Ancients

Long before the modern concept of “music technology,” humans used their environment to make sound:

- Prehistoric Instruments: Bone flutes from the Upper Paleolithic period (e.g., the Divje Babe flute, ~40,000 BCE) are among the oldest known instruments. Drums, rattles, and simple wind instruments emerged across early human societies.

- Stringed and Reed Instruments: Harps, lyres, panpipes, and reeds were developed in ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, and China. These instruments featured in rituals, storytelling, and royal courts.

- Music Theory and Tuning Systems: The ancient Greeks explored the science of sound. Pythagoras linked musical intervals to mathematical ratios—a foundational moment for acoustics and music theory.

Crucially, these early tools weren’t just about entertainment—they helped encode religious beliefs, calendar systems, and cosmic order.

B. The Rise of Written Music and Mechanical Devices

- Notation Systems: Around the 9th century CE in Europe, neumes (early symbols) were developed to notate chant melodies. Guido of Arezzo later refined this system with staff lines—enabling reproducible compositions and more complex polyphony.

- The Printing Press: In 1501, Ottaviano Petrucci published the first polyphonic music with moveable type. This democratized music knowledge, increased circulation, and helped standardize musical literacy.

- Mechanical Instruments: From barrel organs and music boxes to the carillon and player piano, mechanical devices allowed music to be “automated” centuries before the digital age.

These tools expanded the reach of music and laid the groundwork for modern music publishing and mechanical reproduction.

C. The Age of Electricity – Sound Becomes Portable and Powerful

The late 19th and 20th centuries brought radical change:

- Phonograph (1877): Thomas Edison’s invention allowed sound to be recorded and replayed—changing music from a transient event to a repeatable experience.

- Gramophones, Vinyl, and Radio: Music became a domestic and social experience. The rise of broadcasting created stars, standardized genres, and connected rural listeners to global sounds.

- Microphones and Amplifiers: Improved audio fidelity enabled new vocal styles (e.g., crooning) and transformed live performance settings.

- Electric Instruments:

- The electric guitar (e.g., Fender Telecaster, Gibson Les Paul) and Hammond organ defined 20th-century popular music.

- Jazz, rock, blues, and funk thrived through amplified sound.

- The electric guitar (e.g., Fender Telecaster, Gibson Les Paul) and Hammond organ defined 20th-century popular music.

Music was now not only heard—it was recorded, mass-distributed, and embedded into everyday life.

D. The Digital Revolution – From MIDI to Mobile

The late 20th century ushered in a digital paradigm that reshaped music forever:

- MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface, 1983): Allowed electronic instruments and computers to communicate. MIDI empowered composers to edit performances like text, opening vast creative possibilities.

- Synthesizers and Samplers: Artists like Kraftwerk, Wendy Carlos, and later Daft Punk popularized machine-generated sound.

- Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs): Software like Logic Pro, Pro Tools, and FL Studio allowed musicians to record, arrange, and mix at home with near-professional results.

- Auto-Tune and Effects: Real-time pitch correction and vocal manipulation blurred the line between voice and instrument.

These tools revolutionized who could make music, lowering barriers for amateurs while raising questions about authenticity and authorship.

E. Streaming and the Algorithmic Era

In the 21st century, music is more accessible—and more data-driven—than ever before:

- Streaming Platforms: Services like Spotify, Apple Music, and YouTube have transformed how people discover and consume music, shifting power from labels to platforms and algorithms.

- Social Media and Virality: TikTok and Instagram can catapult unknown musicians into the spotlight within hours.

- Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning:

- AI systems can now compose music in the style of Bach, The Beatles, or bespoke emotional tones.

- Tools like OpenAI’s MuseNet or Google’s Magenta explore creative collaboration between human and machine.

- AI systems can now compose music in the style of Bach, The Beatles, or bespoke emotional tones.

- Immersive Technologies:

- Virtual concerts, VR music videos, and spatial audio experiences (e.g., Dolby Atmos) are redefining the sonic experience.

- Virtual concerts, VR music videos, and spatial audio experiences (e.g., Dolby Atmos) are redefining the sonic experience.

Technology has made music ubiquitous, personalized, and collaborative—but it has also raised new questions about intellectual property, saturation, and the role of human creativity.

Conclusion of Section III:

The history of music technology is the history of human imagination externalized into sound. From animal bones to digital code, each new tool has expanded music’s potential—and musicology helps us understand not just how these tools work, but how they change what it means to make and hear music.

IV. Contemporary Research at Cambridge University

Exploring Music Through Mind, Data, and Design

The University of Cambridge has long been a hub of intellectual and artistic innovation, and its Faculty of Music remains at the forefront of modern musicological research. Far from being confined to dusty scores or distant composers, Cambridge’s musicologists are actively shaping how we understand music today—through data, psychology, cognition, and performance.

Here are some of the key research areas being explored at Cambridge:

1. Music Cognition

How does the brain process music? Why do some melodies move us to tears while others inspire action?

Cambridge researchers investigate the neurological and psychological foundations of music perception. Topics include:

- Auditory imagery and how we “hear” music in our minds.

- How infants and adults develop musical preferences.

- Emotional responses to musical structure and tempo.

- Cognitive mechanisms behind rhythm, harmony, and memory.

This work overlaps with neuroscience and education, informing fields like music therapy, learning disabilities, and emotional development.

2. Empirical Music Analysis

What can large datasets and statistical tools teach us about music’s inner structure?

Empirical music analysis applies rigorous quantitative methods to musical questions. At Cambridge, this includes:

- Analyzing hundreds of compositions to identify common harmonic or rhythmic patterns.

- Mapping stylistic changes across centuries using computational models.

- Using digital encoding of scores (e.g., MusicXML) to explore the syntax of musical language.

These approaches help musicologists move beyond subjective description toward verifiable patterns in musical creativity.

3. Empirical Performance Studies

What makes a performance expressive? How do musicians interpret scores differently in real-time?

This area focuses on live performance as a research object. Cambridge scholars study:

- Timing variations (rubato), articulation, and dynamics in recorded performances.

- How bodily gestures, facial expressions, and stage presence affect audiences.

- How performance choices change over time, across cultures, or between traditions.

By combining performance recordings with data analysis, researchers reveal the subtle artistry and psychology of interpretation.

4. Individual Differences in Music Psychology

Why do some people love jazz while others love metal? Why are some people more rhythmically inclined than others?

Cambridge investigates how personality traits, cultural background, and cognitive styles influence musical experience. Projects explore:

- Genetic and environmental factors in musical talent and learning.

- Variability in absolute pitch, memory for melodies, and rhythmic accuracy.

- Links between musical training and non-musical skills like language acquisition or emotional regulation.

Such studies inform educational practices and offer insight into music as both a universal and highly individual experience.

5. Music Learning Aids

How can we help people of all abilities learn, read, and enjoy music?

The Cambridge team develops tools and interventions that enhance musical learning, including:

- Visual and auditory aids for children, including those with dyslexia or ADHD.

- Interactive digital platforms for teaching music theory and performance skills.

- Collaborative learning software that supports ensemble training and self-paced study.

These projects blend music education, design thinking, and cognitive science to make music more accessible to all.

6. Software for Behavioural Experiments

How do we study music listening in a controlled but realistic way?

Cambridge researchers design custom software platforms to study musical behavior in both laboratory and online environments. These platforms allow for:

- Real-time response tracking (e.g., tapping to a beat).

- Emotion rating during musical passages.

- Decision-making studies around musical preference, novelty, and repetition.

This field is at the intersection of psychology, computer science, and user experience design.

7. Score Design for Music Reading

Can we redesign notation to make music easier to read, learn, and perform?

Traditional Western notation, while powerful, can pose challenges to beginners, dyslexic readers, or those with visual impairments. Cambridge researchers are:

- Studying how font style, spacing, and symbol shape affect music reading speed and accuracy.

- Experimenting with color-coded, simplified, or spatial notation systems.

- Exploring how different forms of notation influence musical memory and performance fluency.

These innovations aim to make music literacy more inclusive and ergonomic in both educational and professional settings.

Conclusion of Section IV:

At Cambridge, musicology is not just about understanding music’s past—it’s about shaping its future. Through empirical research, cognitive science, and technological innovation, scholars are rethinking how we teach, experience, and study music in the 21st century. Their work reminds us that music is not only a cultural artifact, but a living, breathing domain of human inquiry and possibility.

V. Conclusion – The Future of Musicology

Where Sound Meets Science, and Culture Meets the Cosmos

Music is often thought of as ephemeral—something fleeting, emotional, mysterious. Yet musicology reveals it to be a rich domain of inquiry, one that spans logic and feeling, history and innovation, science and soul.

From the breath of a bone flute in a Paleolithic cave to a symphony rendered in machine code, music has followed—and helped shape—the arc of human civilization. It has echoed through temples, palaces, slave ships, jazz clubs, concert halls, bedrooms, and satellites. Wherever there are people, there is music—and wherever there is music, there is something to study, something to feel, something to discover.

Today, musicology is more expansive than ever before:

- It is global, embracing traditions from all continents and cultures.

- It is interdisciplinary, linking music with neuroscience, psychology, linguistics, computer science, and philosophy.

- It is technological, using algorithms and AI to analyze patterns and create new sounds.

- It is personal and political, examining how music shapes identity, protest, healing, and memory.

- It is educational and ethical, striving to make music learning inclusive and accessible to all.

And in the face of rapidly evolving technologies, ecological upheaval, and social change, musicology is also becoming futurist—asking what roles music might play in a transformed world.

What will it mean to create music in collaboration with AI?

Can rhythm help us rehabilitate memory or speech in clinical settings?

How might we preserve endangered musical traditions in a digital age?

Could music help reconnect fragmented societies or heal individual trauma?

Musicology doesn’t just ask what music is. It asks what music does—and what it can still become.

As the field continues to grow, it will need both rigor and imagination, data and heart. It will need scientists, artists, coders, archivists, healers, and dreamers. Because music is not one thing—it is many things woven together in vibration, in time, in consciousness.

In studying music, we study ourselves: our minds, our cultures, our longings, and our capacity to make beauty in a world that often needs it most.