Table of Contents

- Introduction – Life, Change, and Loss

The Fragile Symphony of Earth’s Inhabitants - Evolution – The Engine of Life’s Diversity

How Change Becomes Survival, and Survival Becomes Legacy - A History of Extinction on Earth

Ruin and Renewal in the Great Story of Life - The Sixth Extinction – Humanity’s Role in the Great Undoing

A Planet Transformed by One Species - How Many Species Have Lived—and Are Living—on Earth

Life’s Countless Experiments in a Mortal World - Endangered Species – Choices and Consequences

What Do We Save When We Save a Species? - The Future of Extinction – Humanity on the Edge

When the Agents of Extinction Face Their Own - Conclusion – From Dodos to Destiny

What Extinction Teaches Us About Ourselves

I. Introduction – Life, Change, and Loss

The Fragile Symphony of Earth’s Inhabitants

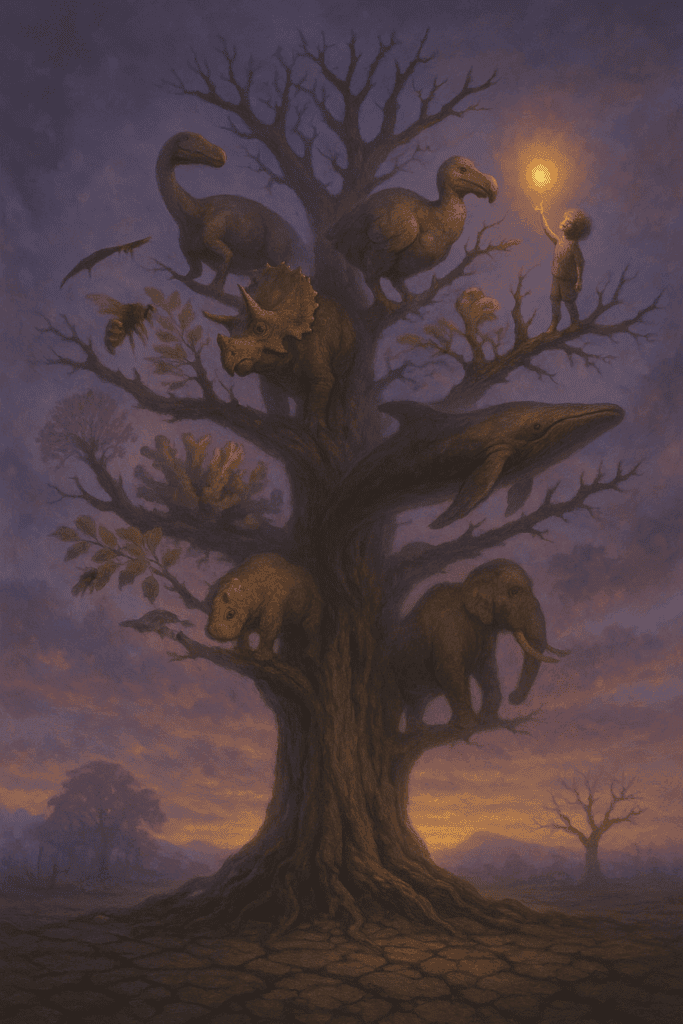

Life on Earth is a triumph of complexity. From single-celled microbes to blue whales, from ferns to fungi to feathered songbirds, the biosphere hums with invention. But this abundance is not guaranteed. Beneath every verdant rainforest, every coral reef, and every open sky where birds once wheeled freely, there lies an ancient truth: life is not only made—it is unmade.

Extinction is the counterpart to evolution. It is not an aberration, but a feature of life’s long history. Species arise, flourish, and vanish. Some are wiped out in great cataclysms. Others fade away through slow attrition. A few leave descendants. Most leave only fossils and echoes in DNA.

Over 99% of all species that have ever existed are gone.

Some disappear without warning. Others decline before our eyes. The dinosaur, the dodo, and perhaps someday, even humans, share a common fate: they are part of Earth’s experiment in adaptation and impermanence.

This article explores the interwoven stories of evolution and extinction, tracing how life evolves through mutation and natural selection—and how it is sculpted by catastrophe, competition, and now, increasingly, by human hands. It examines the five great extinction events of the past, the human-driven sixth extinction underway, and the species—plants, animals, and even cultures—that have vanished or teeter on the brink.

And it asks difficult questions:

- Can extinction ever be reversed or forestalled?

- What value do endangered species hold for a planet in crisis?

- Will humanity itself one day vanish, another chapter in the fossil record?

By tracing this arc, from dinosaurs to dodos to humans, we do not only tell the story of disappearance. We trace the story of transformation—of life’s continual remaking, and of the moral and ecological crossroads at which we now stand.

II. Evolution – The Engine of Life’s Diversity

How Change Becomes Survival, and Survival Becomes Legacy

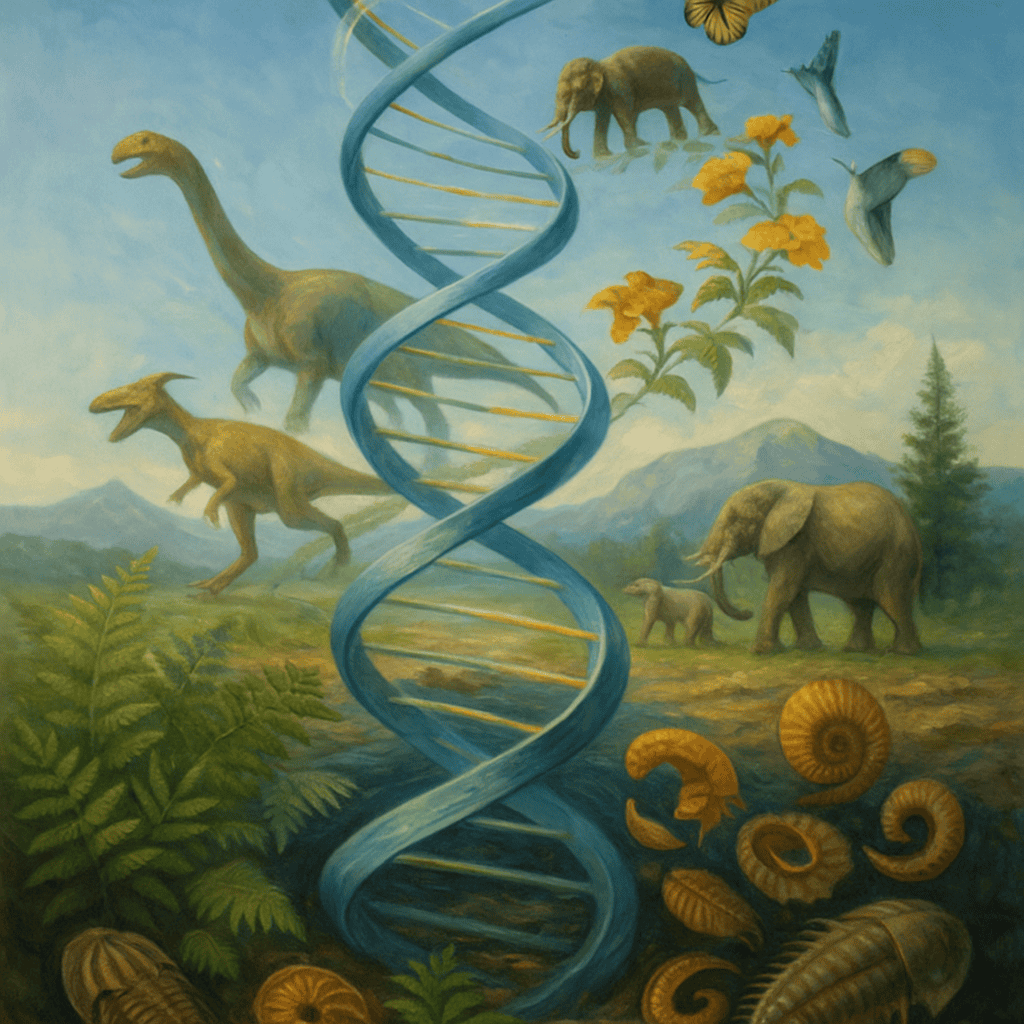

All life on Earth is connected by a common thread: descent with modification. This is the central insight of evolutionary theory, first formulated by Charles Darwin and refined by generations of scientists. Evolution explains the variety of species on Earth—not as separate creations, but as branches on the same great tree of life, diverging over time through the forces of mutation, selection, and inheritance.

The Basics: Variation, Selection, and Inheritance

At the heart of evolution are three key principles:

- Variation: Within any population, individuals differ—physically, behaviorally, and genetically. These differences may be visible (beak shape, fur color) or hidden (enzymatic efficiency, disease resistance).

- Inheritance: Some of these traits are heritable—passed from parents to offspring through genes.

- Natural Selection: In a given environment, certain traits offer survival or reproductive advantages. Those who possess these traits are more likely to pass them on. Over generations, the population evolves.

This process is slow, cumulative, and often blind. There is no “goal” or “ideal” form—only adaptive responses to local conditions.

The Modern Synthesis: Genes, Populations, and Speciation

In the 20th century, Darwin’s ideas merged with genetics to form the modern synthesis of evolution:

- Genes are segments of DNA that encode traits

- Populations evolve—not individuals—through changes in gene frequencies

- Speciation occurs when populations become isolated and diverge genetically, forming new species

This synthesis allowed scientists to quantify evolutionary change and trace evolutionary relationships through molecular biology.

Mutation: The Raw Material of Evolution

Mutation is the source of all genetic variation. It occurs when the genetic code (DNA) is altered. Mutations can arise from:

- Replication errors during cell division

- Radiation (e.g., UV light, cosmic rays)

- Chemical exposure (natural or artificial)

- Viruses inserting genetic material into host DNA

Traditionally, mutations are considered random in origin—that is, they occur without regard to their usefulness to the organism. Natural selection, not mutation, is what favors or filters traits based on environmental pressures.

However, recent evidence reveals that the randomness of mutation is more nuanced than previously thought.

The Non-Random Patterns Within Random Mutation

While mutations are still considered random with respect to fitness outcomes, they are not uniformly distributed across the genome. Several factors influence where and how often mutations occur:

- DNA Sequence Composition: Some nucleotide combinations are more prone to replication errors.

- DNA Repair Mechanisms: These systems can prioritize the correction of mutations in highly conserved or vital genomic regions, resulting in fewer mutations in functionally critical genes.

- Environmental Stress: While harmful agents like UV radiation or chemicals increase mutation rates, they do not direct mutations toward beneficial outcomes. However, environments may create conditions in which certain beneficial mutations are more likely to persist.

- Adaptive Mutation Hypotheses: Some studies suggest that under certain stress conditions (e.g., nutrient deprivation or disease), cells may upregulate error-prone DNA repair mechanisms, potentially increasing genetic diversity in times of need.

- Population-Level Effects: The Luria-Delbrück experiment famously showed that bacterial resistance mutations pre-exist before antibiotic exposure—not induced by it. This supports the random mutation model, but also highlights how selection shapes which mutations survive, not when they occur.

One famous example is the HbS mutation in the hemoglobin gene, which offers resistance to malaria. This mutation is more common in populations historically exposed to malaria. While it likely arose randomly, its prevalence is shaped by strong selective pressure—a demonstration of how environment filters randomness into advantage.

Other Forces of Evolution

Besides natural selection and mutation, evolution is also driven by:

- Genetic Drift: Random changes in gene frequency, especially in small populations

- Gene Flow: Migration of genes between populations (e.g., via interbreeding)

- Artificial Selection: Human-directed breeding of plants and animals (e.g., dogs, crops)

- Sexual Selection: Traits favored not for survival, but for attracting mates (e.g., peacock feathers)

These forces can accelerate, constrain, or redirect evolutionary trajectories.

Innovation and Extinction: Two Sides of the Evolutionary Coin

Evolution is creative—but it is also ruthlessly pragmatic. When environments change, traits once beneficial may become liabilities. If a species cannot adapt quickly enough, it disappears.

Yet extinction clears space for new life. The disappearance of dinosaurs allowed mammals to rise. The loss of dominant species often reshapes ecosystems, creating new opportunities for evolution.

Thus, the engine of life is both a force of change and a reckoner of limits.

In the next section, we explore evolution’s counterpart: extinction—how it has reshaped life’s trajectory across billions of years, and how Earth’s biosphere has weathered cycles of ruin and renewal.

III. A History of Extinction on Earth

Ruin and Renewal in the Great Story of Life

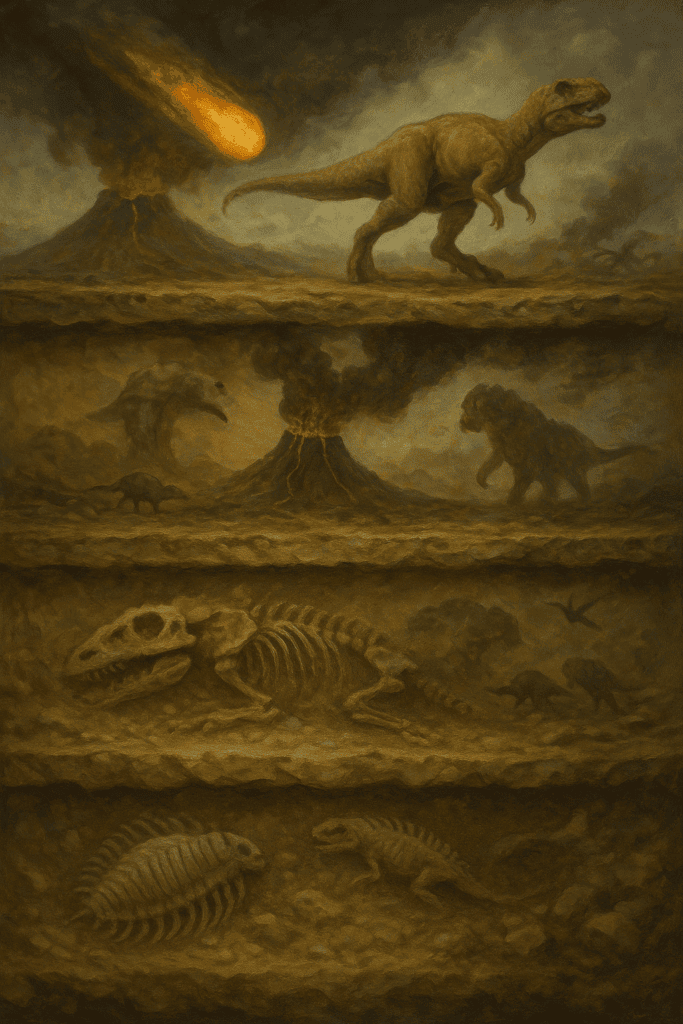

Extinction is the price of evolution’s ambition. Life adapts, expands, and diversifies—but it also falters. From microscopic microbes to towering reptiles, most species that have ever lived have vanished. In the long memory of the Earth, extinction is not the exception. It is the rule.

While extinction can occur slowly, one species at a time, Earth’s history is punctuated by moments of mass extinction—periods when vast numbers of species disappeared in relatively short spans of geologic time. These cataclysms reshaped the tree of life, eliminating dominant groups and allowing new forms to emerge.

The “Big Five” Mass Extinctions

Paleontologists recognize five major extinction events, known as the “Big Five,” which dramatically altered the course of life on Earth:

1. Ordovician–Silurian Extinction (~444 million years ago)

- Caused by glaciation and sea level drop

- ~85% of marine species lost, including many trilobites and brachiopods

- Affected mostly shallow marine ecosystems

2. Late Devonian Extinction (~375 million years ago)

- Possibly caused by ocean anoxia, plant-driven climate shifts, and asteroid impact

- ~75% of species lost

- Coral reefs collapsed; jawless fish largely disappeared

3. Permian–Triassic Extinction (~252 million years ago)

“The Great Dying”

- The most severe extinction event in Earth’s history

- ~95% of marine species and ~70% of terrestrial species perished

- Likely caused by massive volcanic eruptions (Siberian Traps), methane release, global warming, ocean acidification, and low oxygen

- Cleared the way for the rise of dinosaurs

4. Triassic–Jurassic Extinction (~201 million years ago)

- Likely caused by volcanic activity and climate disruption during the breakup of Pangaea

- ~80% of species lost

- Allowed dinosaurs to become dominant on land

5. Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) Extinction (~66 million years ago)

- Caused by a massive asteroid impact near modern-day Yucatán Peninsula

- ~75% of species lost, including all non-avian dinosaurs, ammonites, and many plants

- Enabled the rise of mammals, birds, and flowering plants

Common Causes of Mass Extinction

Despite their differences, these events share common causes:

- Climate shifts (sudden cooling or warming)

- Volcanic eruptions altering atmosphere and oceans

- Asteroid or comet impacts with global fallout

- Ocean anoxia and acidification

- Sea level changes disrupting marine habitats

- Tectonic events changing geography and climate

Mass extinctions are Earth’s resets—brutal pruning events that allow new evolutionary experiments to begin.

Background Extinction: The Ongoing Pulse

Not all extinctions occur in dramatic bursts. Background extinction is the normal rate at which species disappear due to environmental changes, competition, disease, or random chance.

- Estimated background extinction rate: ~1 species per million species per year

- This is the “heartbeat” of natural turnover in ecosystems

- Most species are short-lived in evolutionary terms—lasting 1–10 million years

Mass extinctions occur when extinction rates exceed background rates by orders of magnitude.

Extinction as a Creative Force

Paradoxically, extinction is not only an end. It is also a driver of innovation.

- The collapse of one ecological system allows another to rise

- Extinction reduces competition, opens niches, and frees evolutionary pathways

- After the dinosaur extinction, mammals rapidly diversified into the forms we know today

Extinction, though tragic in the moment, is often the prologue to transformation.

As we now face what scientists call a potential “Sixth Mass Extinction,” the lessons of the past grow ever more urgent. The next section explores how human activity is accelerating extinction, reshaping Earth’s biosphere in ways both subtle and catastrophic.

IV. The Sixth Extinction – Humanity’s Role in the Great Undoing

A Planet Transformed by One Species

We are not merely witnessing the sixth mass extinction—we are causing it. Unlike past cataclysms triggered by asteroids or volcanoes, the current wave of extinction has a single origin: human civilization. Since the rise of agriculture and industry, human beings have altered the Earth more profoundly—and more rapidly—than any force before them.

Species are now vanishing at a rate estimated to be 100 to 1,000 times faster than the natural background extinction rate. The changes we’ve set in motion are so vast, scientists argue that we’ve entered a new epoch: the Anthropocene, the Age of Humans.

A Holocene World Unraveled

The Holocene epoch, which began ~11,700 years ago after the last Ice Age, saw the flourishing of biodiversity and the emergence of human civilizations. But as agriculture, settlement, and technology advanced, humanity began to:

- Convert wilderness to farmland and cities

- Overhunt and overfish wildlife populations

- Pollute air, water, and soil with chemicals and waste

- Introduce invasive species across continents

- Disrupt climate and ecosystems at global scale

The result is a cascading collapse of biodiversity.

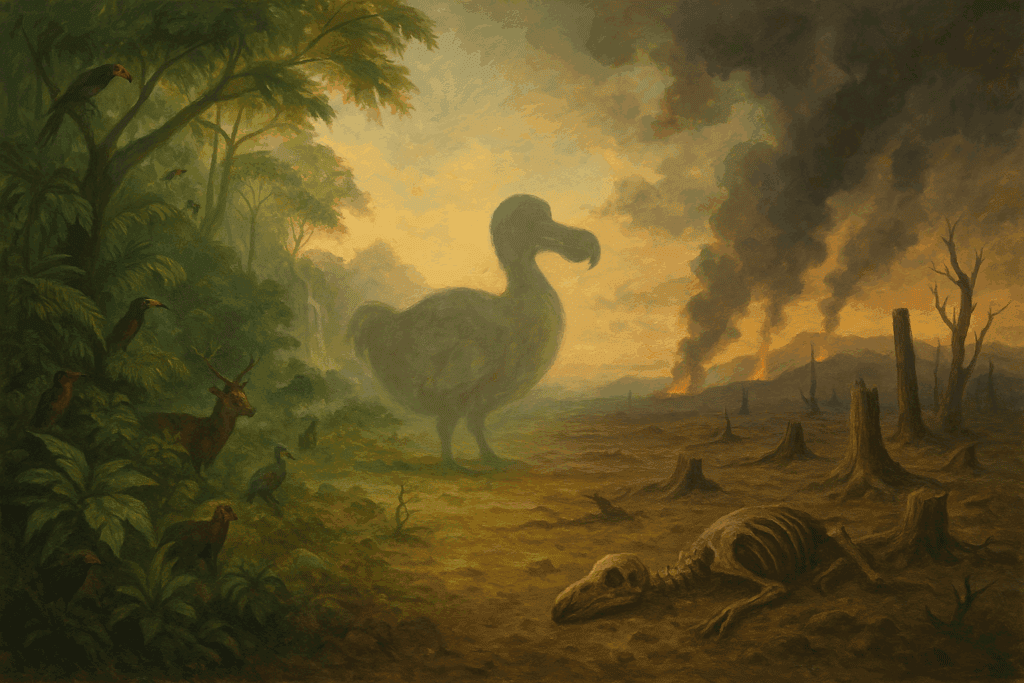

Iconic Extinctions: From the Dodo to the Megafauna

Since recorded history began, humans have directly caused the extinction of hundreds of species, including:

- Dodo (Raphus cucullatus) – Flightless bird hunted to extinction by 1681

- Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) – Once in the billions; extinct by 1914

- Great Auk, Steller’s Sea Cow, Aurochs – Victims of hunting and habitat loss

- Moas, Giant ground sloths, Woolly mammoths – Disappeared after human arrival in new continents

The pattern is tragically familiar: a species encounters humans, and within a few centuries—or decades—it vanishes.

Modern Drivers of the Sixth Extinction

- Habitat Destruction

- Deforestation, especially in the Amazon, Congo, and Southeast Asia

- Urban sprawl and infrastructure slicing up wildlands

- Wetland draining and coral reef bleaching

- Deforestation, especially in the Amazon, Congo, and Southeast Asia

- Overexploitation

- Industrial fishing fleets collapse marine ecosystems

- Poaching and illegal wildlife trade threaten rhinos, pangolins, elephants

- Industrial fishing fleets collapse marine ecosystems

- Pollution

- Pesticides decimate insect populations

- Plastic and chemical runoff poison oceans and food chains

- Air pollution drives respiratory and ecosystem damage

- Pesticides decimate insect populations

- Invasive Species

- Cane toads, zebra mussels, and rats outcompete or prey upon natives

- Globalization spreads pathogens and alien predators rapidly

- Cane toads, zebra mussels, and rats outcompete or prey upon natives

- Climate Change

- Rising temperatures shift habitats faster than species can adapt

- Melting ice, sea level rise, and extreme weather stress ecosystems

- Ocean acidification dissolves coral reefs and disrupts marine life

- Rising temperatures shift habitats faster than species can adapt

A Planet Reweighted: Fewer Species, More Biomass

While wild species decline, a few domesticated ones explode in number:

- 60% of global mammalian biomass: livestock (mostly cattle and pigs)

- 36%: humans

- Only 4%: wild mammals

Similarly:

- 70% of all bird biomass: chickens

- Fish farms now rival wild catches

- Insect populations have plummeted in many regions, with unknown ecological consequences

Earth is being transformed from a rich tapestry of wild species to a biologically simplified machine of industrial production.

The Cost of Loss

Biodiversity loss is not just an aesthetic or ethical concern—it has real consequences:

- Ecosystem services: pollination, water purification, soil formation, climate regulation

- Resilience: diverse ecosystems recover better from shocks

- Medicine: many drugs are derived from plants and animal compounds

- Cultural and spiritual value: the sacredness of animals in Indigenous traditions, symbolism, and human identity

What we are losing is not just species, but the memory and potential of life—billions of years of adaptive wisdom, discarded in the name of short-term gain.

In the next section, we quantify this transformation, comparing existing species with those that have already gone extinct, and estimating how many forms of life Earth has nurtured—and lost.

V. How Many Species Have Lived—and Are Living—on Earth

Life’s Countless Experiments in a Mortal World

Earth has been a living planet for over 3.5 billion years, and in that time, it has hosted an extraordinary abundance and diversity of life. From single-celled archaea in deep-sea vents to towering dinosaurs, flowering trees, fungi, birds, and humans, evolution has generated a staggering array of forms—most of which no longer exist.

But how many species has Earth actually hosted? And how does the current biosphere compare to the legacy of life already lost?

How Many Species Exist Today?

Estimates vary, but scientists believe there are roughly:

- ~8.7 million eukaryotic species on Earth (plants, animals, fungi, protists)

- Of these, only about 1.2–1.5 million have been formally described

- This includes:

- ~1 million animals (with insects dominating)

- ~400,000 plants

- ~150,000 fungi

- Unknown numbers of bacteria and archaea—possibly trillions of microbial species

- ~1 million animals (with insects dominating)

Most species on Earth remain undiscovered or unnamed, particularly among insects, deep-sea organisms, soil microbes, and tropical rainforest biota.

The Total Number of Species That Have Ever Lived

Paleontologists estimate that over 99% of all species that have ever lived are now extinct.

- Estimates range from 500 million to over 1 billion species in Earth’s history

- The fossil record captures only a tiny fraction of extinct life, biased toward organisms with hard parts and those living in preservable environments

- Most species existed for 1–10 million years before going extinct or evolving into something new

Life, it seems, is a continuous experiment—with most results abandoned.

Number of Individual Organisms

While counting species is daunting, counting individuals is even more so:

- Estimates suggest ~20 quintillion (2 × 10²²) individual animals on Earth

- Insects alone may account for 10 quintillion (10¹⁹) individuals

- Microbial life dwarfs all others: in a single gram of soil, there may be billions of bacteria

In Earth’s past, the total number of individual organisms that have lived—bacteria, plants, animals—is beyond calculation. But it likely reaches 10³⁰ or more.

Life has filled every niche, multiplied, died, and repeated itself across the eons.

The Unseen Legacy of Extinction

Most species leave no trace:

- They may never have fossilized

- They may have lived in fragile environments

- They may have been wiped out before discovery

Every extinction deletes not only a form of life, but a unique configuration of genes, behaviors, and ecological relationships. The more species that vanish unrecorded, the more we lose irreplaceable information about how life works.

A Living Planet, Heavily Pruned

Today, the biosphere is both rich and impoverished. Millions of species persist, but their ranges are shrinking. Many populations are in decline. And the rate of extinction continues to climb.

We are the stewards of a planet where life has flourished for billions of years—and where much of that flourishing has ended. The question is whether we will become the custodians of what remains, or the authors of another layer of silence in the fossil record.

Next, we turn from historical and numerical perspectives to moral and practical ones: how do we respond to endangered species? What do we save, and why?

VI. Endangered Species – Choices and Consequences

What Do We Save When We Save a Species?

As species disappear at unprecedented rates, we are faced with urgent, complex, and deeply human questions:

Which species deserve to be saved? Can all of them be saved? And what does it cost—ecologically, financially, morally—not to try?

An endangered species is not yet extinct, but it is on the path. In the wild, numbers have dwindled. Habitats have shrunk. Genetic diversity is thinning. Every endangered species is a living echo—a heartbeat in a vanishing world—and a decision point in the Anthropocene.

What Makes a Species Endangered?

A species is considered endangered when it faces a very high risk of extinction in the near future. Factors include:

- Population size: low numbers or declining trends

- Range: restricted or rapidly shrinking habitat

- Genetic bottlenecks: reduced gene pools make adaptation harder

- Reproductive rate: low birth rates or high infant mortality

- External pressures: poaching, pollution, habitat loss, climate stress

The IUCN Red List categorizes species as Vulnerable, Endangered, Critically Endangered, Extinct in the Wild, or Extinct.

Living on the Brink: Notable Endangered Species

Some species have become icons of extinction risk and conservation:

- Giant Panda: no longer officially listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), its status has been upgraded from “endangered” to “vulnerable,” meaning they are still at risk.

- Orangutan: critically endangered due to habitat loss and fragmentation caused by deforestation, particularly for palm oil plantations

- Amur Leopard: fewer than 100 left in the Russian Far East

- Vaquita: a porpoise in the Gulf of California—possibly fewer than 10 remain

- Javan Rhino: critically endangered, with a single wild population

- Axolotl: a Mexican amphibian nearly gone in the wild, now mostly in captivity

- Philippine Eagle: among the rarest birds of prey, with habitat under siege

Thousands of less-famous species also face decline: orchids, freshwater mussels, insects, amphibians, reef fish, and forest birds. Many will vanish without ever being named.

The Cost of Conservation

Saving species can be expensive, and decisions are sometimes controversial:

- Breeding programs, habitat preservation, and enforcement against poaching can cost millions

- Not all species can be saved, raising debates about ecological triage: Should we prioritize species that are easier or cheaper to save?

- Critics argue that focusing on charismatic megafauna (e.g., pandas, elephants) may divert resources from less-visible but ecologically vital organisms

Yet the cost of extinction may be far greater in the long run—through ecosystem collapse, loss of agricultural pollinators, degradation of air and water quality, or cultural and scientific impoverishment.

Why Save Endangered Species?

- Ecological Role: Every species plays a part in ecosystems—pollinators, decomposers, predators, prey. Removing one can ripple through the whole system.

- Genetic Value: Species contain unique genes and biochemical pathways that may offer future medical, agricultural, or technological insights.

- Cultural and Ethical Responsibility: Many species are sacred, symbolic, or historically meaningful to Indigenous cultures and local communities.

- Aesthetic and Spiritual Value: Biodiversity enriches human experience—through wonder, beauty, and the sense that we live in a shared web of life.

Can Extinction Be Reversed?

Emerging technologies like cloning, CRISPR gene editing, and de-extinction proposals (e.g., reviving mammoths or thylacines) raise hopes—and ethical questions.

- De-extinction efforts remain speculative and controversial

- Focus may be better placed on preserving existing species and ecosystems rather than re-creating lost ones

- The real challenge is not resurrection, but prevention

Every endangered species is a mirror of our values. What we choose to protect—whether it’s a tiger, a frog, or an unknown fungus—reveals who we are and how we relate to the living Earth.

In the final section, we explore what comes next: the future of extinction, and the fate of humanity itself in a rapidly changing world.

VII. The Future of Extinction – Humanity on the Edge

When the Agents of Extinction Face Their Own

Throughout history, humans have driven other species to extinction—intentionally through exploitation, and unintentionally through expansion. But now, for the first time in Earth’s history, a single species holds the power not just to destroy ecosystems, but potentially to erase itself.

Extinction is no longer just a past event or present concern. It is a looming possibility for the architects of the modern world: us.

Human Vulnerability in an Engineered World

Despite our technological dominance, humans remain deeply dependent on ecological stability, climate regulation, and biodiversity. As these pillars falter, so too does the civilization they uphold.

Potential drivers of human extinction—or civilizational collapse—include:

- Climate Change

- Sea level rise, extreme heat, ecosystem failure, crop collapse, climate migration

- Sea level rise, extreme heat, ecosystem failure, crop collapse, climate migration

- Nuclear War

- Direct devastation followed by “nuclear winter,” ecosystem collapse, and global famine

- Direct devastation followed by “nuclear winter,” ecosystem collapse, and global famine

- Pandemics

- Natural or bioengineered pathogens spreading faster than our ability to contain them

- Natural or bioengineered pathogens spreading faster than our ability to contain them

- Artificial Intelligence

- Uncontrolled AGI (artificial general intelligence) scenarios with unintended consequences

- Uncontrolled AGI (artificial general intelligence) scenarios with unintended consequences

- Ecological Tipping Points

- Collapse of pollinator populations, ocean food chains, or Amazonian rainforests

- Collapse of pollinator populations, ocean food chains, or Amazonian rainforests

- Biotechnology & Gene Editing

- Accidental or malicious genetic engineering of invasive organisms or viruses

- Accidental or malicious genetic engineering of invasive organisms or viruses

- Resource Exhaustion

- Water scarcity, soil degradation, energy shortages destabilizing food systems

- Water scarcity, soil degradation, energy shortages destabilizing food systems

While none of these threats guarantee extinction, they each chip away at the complexity and coordination required to maintain a global civilization.

Will We Be the First to Know—and the First to Choose?

Unlike any other species, humans can anticipate their extinction. We can model the consequences, predict tipping points, and take proactive action. This is a profound privilege—and an even greater responsibility.

Whether we face collapse in centuries, decades, or not at all depends largely on:

- Global cooperation and long-term governance

- Science-based policy and risk assessment

- Ecological restoration and sustainable resource use

- Equity and resilience across cultures and nations

History shows us how fragile societies can be. But it also shows us the power of adaptation.

Could Life Begin Again?

If humanity were to vanish, life would almost certainly continue—though poorer in diversity, and altered by human legacy. Given time, intelligent life could evolve again, but there are no guarantees:

- It took over 500 million years of animal evolution for humans to arise

- Without large-brained mammals, intelligent successors could take much longer—or never arise

- Earth’s habitability will not last forever—climate and solar cycles will eventually end this chapter

In this light, humanity is not just a species. We are a possibility—a fleeting synthesis of biology, consciousness, and culture that may never occur again.

Toward a Future Worth Surviving

Extinction is final. But collapse is not. The future need not be dystopian, nor doomsday. It can be regenerative, wise, beautiful. This requires a shift:

- From extraction to stewardship

- From dominion to coexistence

- From short-term exploitation to long-term resilience

Our challenge is not just to survive—but to live in a way that life itself can continue to flourish.

In the concluding section, we reflect on what extinction teaches us—not only about biology and geology, but about ethics, meaning, and the kind of ancestors we choose to be.

VIII. Conclusion – From Dodos to Destiny

What Extinction Teaches Us About Ourselves

Extinction is more than the loss of species. It is the loss of possibility, of ancient genetic symphonies, of ecological partnerships crafted over millions of years. It is a thinning of the world’s meaning, and a narrowing of its future.

The story of extinction is not a separate tale from the story of life. It is one of its essential chapters. But now, for the first time in Earth’s history, a species has emerged that can understand extinction, measure its causes, and choose a different path. That species is us.

And so the question is no longer merely biological. It is moral, political, cultural. What kind of beings will we be, knowing what we know?

The Power—and Burden—of Choice

We have the capacity to be destroyers or stewards. In the past century alone, we’ve eliminated entire species—and also brought others back from the brink. We have reshaped the biosphere—and also mapped it, studied it, and protected large portions of it.

But the scale of the crisis now demands more than scattered acts of goodwill. It requires a transformation of our worldview.

Toward a Scientific Human Future

This transformation must be grounded in truth, compassion, and cooperation—the hallmarks of an ethical civilization. It must balance reason with reverence for life, and innovation with interdependence. Such a framework exists: Integrated Humanism—a synthesis of Secularism, Science, Democracy, and Humanism—offers a path forward that is neither mystical escapism nor technological nihilism.

Integrated Humanism insists that:

- We ground our decisions in evidence and humility

- We value all life, not just human profit

- We take responsibility for the systems we’ve inherited and disrupted

- We treat future generations as stakeholders in the choices we make now

Science Abbey: A Temple for Earth’s Future

This philosophy is embodied in projects like Science Abbey—a community and platform dedicated to nurturing an ethically grounded, scientifically literate, and ecologically awakened humanity. Science Abbey envisions a world in which knowledge and virtue are not divorced, but wedded into a new form of wisdom—one that honors both the atom and the animal, the data and the forest, the algorithm and the child.

Such movements remind us that extinction is not inevitable. It is a consequence—of ignorance, of neglect, of imbalance. And just as we have accelerated the sixth extinction, we can reverse it, if we act with clarity, resolve, and unity.

What Kind of Ancestors Will We Be?

The dodo did not choose extinction. The passenger pigeon did not sign its death warrant. But we can choose.

We can be the species that saw the fire spreading—and put it out. The species that rebuilt wild places, protected the fragile, and ensured that the planet remained a living, singing, evolving world.

Or we can be the last voice, echoing in a silent forest.

This is the story of transformation and extinction. But it is also the story of awakening—and the responsibility that comes with it.

Let us write the next chapter not as witnesses to loss, but as guardians of continuity. Let us become not the end of nature, but its conscious protector.

Let us become worthy of the life that made us.