Simple Sitting Meditation

This handbook is a guide to a seated silent meditation, which for the purpose of precise definition, is called Illumination meditation. Feel free to skip the philosophical introduction and go to the end of this article to the brief Meditation Manual with clear instructions how to meditate.

Illumination meditation is the unification of the mind, allowing thoughts and emotions to come and go naturally within the field of awareness, without further purpose. Ideally this state of mind is not limited to sitting, but rather, may be kept throughout the day during all of one’s activities. As simple as it sounds, there is much more to this practice than may at first meet the eye.

This practice cultivates many benefits, such as stress-reduction, increased health, and cognitive improvement. It may produce an awareness of complete oneness, known as enlightenment, but even this kind of higher consciousness comes and goes. Illumination meditation is illuminating; and this illumination is an end in itself.

This article offers a technical manual for the practitioner. There are many types of meditation in the world, with various results intended. Illumination meditation embodies wholeness: the unperturbed, pure essence of the mind, awake to the oneness of the cosmos, not clinging to any thoughts or feelings.

As a foundational principle, Science Abbey makes no claims that contradict scientific inquiry. There are about 4,200 religions in the world today and many systems of meditation and mystical experience. Some spiritual claims are less benign or expedient than others, and some are just outright false.

There are a multitude of legitimate methods of insight and living well and no two people’s philosophy and practice will be exactly the same. Science Abbey investigates various approaches in ongoing research. According to studies, Illumination meditation and the lifestyle that supports it do bear the fruit of health, happiness and enlightenment.

Reading or hearing about it and understanding it is not the same as doing it and experiencing it. Here is your chance to try it and see if it works for you.

JUST SIT:

An Inter-denominational /

Non-denominational Practice

This handbook will explore various philosophies, so it is important to note at the start that Science Abbey subscribes to a scientific humanist worldview, rejecting all claims that do not align with science. Various forms of meditation cultivate different faculties for divergent aims and produce varying mental states.

A clear line of transmission can be traced from Indian Yoga, Indian Buddhism and Chinese Daoism to Chinese Chan Buddhism, to Japanese Zen Buddhism, to Western scientific mindfulness meditation. Many adaptations have been made along the way. This family of traditions informs the philosophy and method of Illumination meditation.

The highest goal of sitting meditation is known in the East as Samadhi. This is a common term used in the various Hindu, Jain, Sikh, yogic and Buddhist schools. For thousands of years, meditation has been known as a three-fold process: dharana, or concentration; jhana (Sanskrit: dhyana), meditation; and Samadhi, enlightenment or illumination.

Rooted in Ancient Traditions

Yogic practices took shape in India around the sixth century BCE with ascetics following the Hindu, Jain, Buddhist and other religions. These mendicant monks shared the philosophy of samsara, the cycle of birth and death in reincarnation, and liberation from this cycle in moksha, the transcendence of ignorance and suffering. Moksha can simply be an end of suffering, but it may also be mystical oneness with Brahman, the first cause and ultimate reality, the source of all consciousness, knowledge and bliss.

In ancient China the equivalent to Samadhi was known as “immortality,” through returning to the Dao, literally the “Way” or “Path.” Before names exist, the Dao is the self-existent, undifferentiated One. Once things are created, differentiated and may be named, the Dao is the ultimate origin of all things. Daoist philosophical immortality is just returning to this Source and realizing the One.

The two main aspects of Theravada Buddhist meditation are samatha (calm) and vipassana (insight), or bhavana (cultivation). Theravada Buddhism claims that the Buddha practiced Vedic concentration meditation, known as samatha or samadhi bhavana, but that he taught his own form of meditation, vipassana bhavana. Vipassana means “deep perceiving” or “clear seeing,” and is known today as insight meditation.

Insight meditation is said to reveal the underlying reality of all things, which is anicca (impermanence), anatta (the absence of self), and dukkha (suffering or dissatisfaction).

Illumination is known as nibbana (Sanskrit nirvana),[1] literally the “blowing out” of mental disturbances. It indicates stopping the wheel of samsara, the cycle of reincarnation, and ending the cycle of dukkha.

The technique of insight meditation is sati (mindfulness), the moment to moment open awareness of experience.

Mahayana Buddhists like the Chinese Tiantai sect have also historically taught mindful breathing meditation, as described in the Surangama Sutra. The peak experience of Buddhism is also known as bodhi (awakening), the realization of inherent Buddha-nature, or Buddhahood.

In the schools of Yogachara, Shingon and Zen Buddhism, bodhi is the natural, pure, inherent state of mind, the absence of duality, the emptiness that reveals the interconnectedness and essence of the cosmos.

Buddhist Ideas of Enlightenment

In Theravada Buddhism, one who is liberated is known as an arahant (Sanskrit: arhat). Mahayana Buddhism goes further, recognizing two other levels of enlightenment. One who seeks to help all sentient beings attain liberation is known as a Bodhisattva. One who attains complete awakening is known as having Full Buddhahood. The Tiantai school of Buddhism describes six identities culminating in complete Buddhahood. Mahayana scripture reports fifty-two stages along the Bodhisattva Path.

The great Buddhist philosophers have posited that the ultimate state of mind is the one that understands that conditioned mentality and illumination are both a part of life even after enlightenment. Everything is an illusion, all is sunyata (emptiness), or beyond emptiness. Reality is ineffable, indescribable, or tathata, described only as “suchness.”

As all phenomena are impermanent, absolute truth reaches beyond common sense, beyond reason and science, beyond religion, beyond meditation, and even beyond illumination. Illumination sees beyond the duality of enlightened and unenlightened mind. This knowing that all phenomena are empty is expressed as prajna (wisdom), another term for enlightenment.

Transcendent wisdom, or prajna, is the insight into reality that realizes that all is void, impermanent, and suffering. The Sanskrit word “prajna” is derived from the root pra, “higher,” and jna, “knowledge.” The doctrine of the void interprets “voidness” as a state of mind and being.

In Mahayana Buddhism, such as Chinese Chan, meditation (“zuochan”) is the method of cultivating prajna for reaching minor and major awakenings, nirvana and Buddhahood. Wisdom, the function of the illumined mind, manifests as awakening and disciplined, ethical daily living.

Some schools, such as the Jogye Order of Soen (Korean Zen), regard both sudden and gradual enlightenment as part of the Buddhist experience. Once one has the moving realization of essential nature, one should continue to be open to all such experiences, allowing the enlightened perspective to become an integral part of day-to-day life.

The Great Enlightenment is likely not one’s first realization and it is followed by further gradual illumination throughout one’s life as one continually seeks wisdom.

Zen Enlightenment

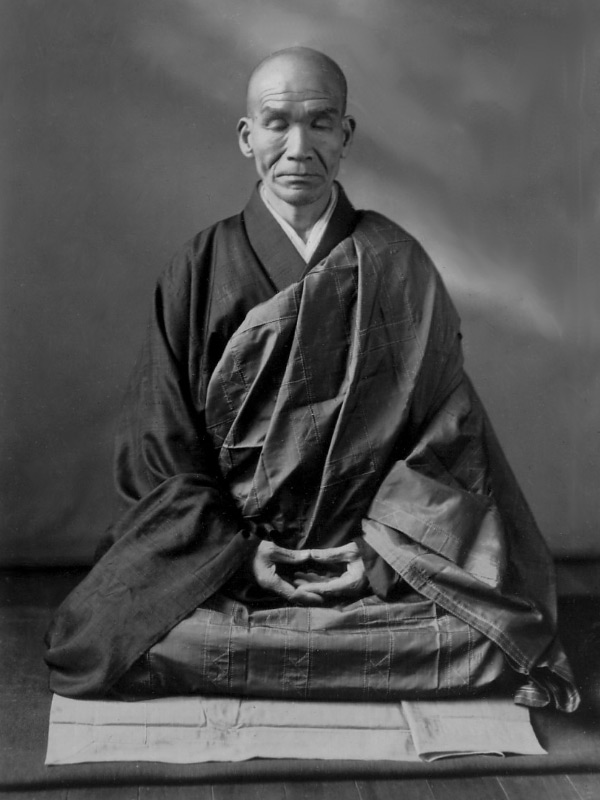

The Japanese Zen Buddhist seeks to increase his or her awareness with meditation called zazen (“seated meditation”) until a final experience occurs, called satori, which is sudden enlightenment. This enlightenment is also characterized as inner silence, or as mu, nothing.

Satori may arise from direct teacher-student contact, koans or meditation. The disciple then works to live this enlightenment in daily life, which means living life as if it were a ritual, living simply and naturally, and living moderately with a healthy diet and exercise.

Kensho is a Japanese Zen Buddhist term used to denote seeing one’s true nature, or Buddha-nature. Some see kensho as having the same meaning as satori, but others view it as a stage of awakening, implying that there is further work to do before reaching the complete awakening to Full Buddhahood.

Rinzai Zen is centered on koans (paradoxical riddles) and satori, while Chinese Chan (from the Caodong school) and Soto zen emphasize mozhao, or “silent illumination.” Rinzai can be said to take the gradual approach due to its reliance on meditating on koans, but it can also be considered as a sudden school, with its focus on satori.

Soto Zen teaches repetitive sudden enlightenment which, as it interpenetrates every aspect of life, is a kind of gradual enlightenment. Eihei Dogen (1200-1253), the founder of the Japanese Soto Zen sect, speaks of daigo, the “Great Enlightenment,” in his Shobogenzo.

Daigo is a sudden enlightenment, a mystical revelation, a spiritual epiphany, described as the direct experience of one’s true nature, one’s “Original Face.” It is also “practice-enlightenment;” the wisdom of ongoing realization.

Western Forms of Meditation

Yogic meditation was the root of the Buddha’s world-view and method. Chan Buddhism evolved in China as a synthesis of the native Daoism and the successful imported Indian religion of Buddhism. Chan was further developed in Korea as Soen Buddhism and in Japan as Zen Buddhism. This meditation only recently came to Europe and America, but the West has kept its own ancient Illumination traditions, albeit in a much less public manner.

At the heart of the Western Mystery Tradition is the Jewish mystical discipline of Kabbalah. Kabbalah may include many visualizations and contemplations. The ultimate meditation is the Ineffable, known as Ein, “the non-existent,” or Ein Sof, “the Endless One.” This abiding in the nameless “One” or “Nothing” is analogous to the silent concentrated awareness of yogic and Buddhist Samadhi.

Kabbalah and Hermeticism, or symbolic alchemy, informed the fraternities of Rosicrucians and speculative Freemasons during the Renaissance and Enlightenment periods. These teachings branched into various schools, such as the Bavarian Illuminati (originally, the Perfectibilists), founded 1776, and later Hermetic societies, like the Victorian era Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and the early twentieth century Argenteum Astrum.

The Christian Benedictine four-step method of meditation Lectio Divina, “Divine Reading,” was developed in the sixth century CE and has been used down to the present day. It includes the step “Contemplatio,” contemplation, which means resting in peace and silent concentrated awareness.

Although the “Creator” is interpreted as a monotheistic god as according to Judeo-Christian scripture and tradition, the mystical communion approached by Contemplatio is the same as the Daoist’s union with the Dao and the yogin’s or Buddhist’s Samadhi.

Yogic and Buddhist meditation techniques incorporating calm and insight were the basis for the Western scientific therapies of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy. These modern medical therapies were established around the turn of the millennium by Jon Kabat-Zinn.

Kabot-Zinn’s science-based therapeutic exercises were popularized as “mindfulness meditation.” The stated aim is health, and the interpretations of the results are secular. However, the operation of mindfulness is just Samadhi, zazen, or Illumination meditation.

This is not to say that interpretation is not important. Worldview and comprehension of Illumination meditation are very important. The Soto Zen instruction on shikantaza, described below, is probably the most direct teaching on the technique of Illumination meditation.

Science, however, will give the most accurate description of the physical and psychological processes involved in Illumination meditation. A complete understanding demands a synthesis of these two traditions.

Meditation Manual

Historically, illumination does not occur only during meditation, although Gautama Buddha was enlightened while sitting in meditation under the bodhi tree. The records of Chan Patriarchs and monks, such as Biographies of Eminent Monks, Transmission of the Lamp, and the Record of Linji, as well as collections of koans like the Blue Cliff Record and The True Dharma Eye describe various ways of reaching enlightenment.

According to the famous Chan story, Buddha’s disciple Mahakasyapa was enlightened when Buddha held up a white flower during his wordless “Flower Sermon.” The famous Chan patriarch Huineng was enlightened upon hearing a line from the Diamond Sutra, “Depending on nothing, you must find your own mind.” Eihei Dogen, the founder of Soto Zen Buddhism, was enlightened when his teacher said that meditation was “sloughing off of body and mind.”

Meditation can and should be done sitting, standing, walking, and going through one’s daily activities. One remains passively mindful, fully aware in the present moment, and the whole mind becomes unified in that awareness. Just sitting, the mind trains itself with wholehearted concentration to see through its own illusions, to let go of the endless stream of thoughts and feelings, and see into the eternal void.

Deep trances alternate with and merge with everyday consciousness. This flux is all a part of illumination and living a good life. Living well involves much more than just meditation, it encompasses everything one does day to day, but Illumination meditation is central to the enlightened life. Living such a good life begins with preparing oneself for Illumination meditation, including cultivating one’s personal environment, posture, hands, gaze, breathing and even the mind.

Environment

A quiet, still, peaceful environment is conducive to a quiet, still, peaceful mind. If possible, use a quiet room, one that contains only natural colors, one that is uncluttered, and preferably remains at a comfortable temperature. Although such arrangements are technically unnecessary, they are advantageous and advisable.

Daoists in ancient China recognized that harmony with nature and good health were vital to meditation practice. Relaxation and concentration are more difficult under stress, pain and illness. This implies that living a healthy and ethical life, as much as possible, is part of the foundation for meditation.

All aspects of Illumination meditation, including preparation, take time to make significant changes in one’s life. It requires some discipline and tenacity. It may take months before a newcomer begins to observe meaningful results. You will get better with constant practice.

There is no need to rush a journey that takes a lifetime. There will always be good days and bad days. In Zen, it is said that everyone is a always a beginner, and this is called “beginner’s mind.” In time, the goalless goal becomes a natural and welcome sanctuary.

One should establish a proper sleep schedule, cultivate a healthy diet, stay hydrated, maintain regular hygiene and vaccinations, get enough exercise and take walks in nature. Habitual, correct study and contemplation are also very important. It is good to speak in public, sing or just read aloud.

One has to have a sufficient income and manage finances for one’s livelihood. One needs to develop good relationships with family, friends, colleagues and community, and wisely participate in politics. Science Abbey articles are centered upon this lifestyle.

Zen practitioners make themselves more comfortable, but not lavishly so, with a mat and a small, round pillow called a zafu. Meditation traditions recommend wearing loose-fitting clothes and adjusting them to accommodate for long periods of sitting.

Beginners may sit for ten or fifteen minutes once or twice every day, eventually increasing the time to half an hour or more. It is common practice to sound a small wooden drum or bell to begin and end the meditation. Bowing is also appropriate.

Posture

There are four traditional ways to sit for sitting meditation that are comfortable for most people. Sitting on a cushion really helps. During meditation, if you get too uncomfortable, you can change from one position to another. As you practice you will be able to sit still much longer. Every individual has different needs. Medical considerations should be taken seriously.

Yogic, Buddhist and Daoist postures are usually safe, but one must use moderation and be careful to avoid over-strenuous positions. An advanced yogic posture is the full lotus, where both heels rest on the opposite leg. The half lotus position is like the full lotus, but the right leg rests completely on top of the left. Knees should both touch the ground. The Burmese position is similar, but legs are not crossed, and the feet rest on the floor.

A simple position, known in Japan as “seiza,” is to fold your legs at the knees and sit on your heels, but put a cushion over your heels. Hands in this posture are usually placed palm down with fingers together on the thighs, or they are placed in the lap. Maybe the most natural posture today is to sit up straight in a chair, resting one’s hands on the knees or in the lap.

Standing, walking and running, like qigong (breathing, movement and visualization exercises), taijiquan (Tai Chi Chuan: “Grand Ultimate Boxing” Daoist martial art) and wushu (Chinese martial arts), are basic, healthy forms of active meditation.

Spine and Breath

Breathing should be soft, quiet, natural and through the nostrils. When the mind wanders in meditation, practice breathing from your center of gravity, about two to three inches below the navel, known as the sacral chakra (Svadhisthana), lower dantian (“Elixir Field”), the hara and the one-point. There is no need to keep the mind on the breath.

Deep breathing will assist your posture, making you conscious of the tilt of your pelvis and lumbar region, and it will become natural with repetition. Notice the breath as it passes through your nostrils. A single deep breath, exhaling through the mouth, is a good way to calm the nerves and stimulate the mind.

This is key – you must keep a very straight spine. Imagine you are balancing a teacup on the crown of your head. The shoulders are relaxed and the chin is slightly tucked in. Imagine a line running vertically through the center of the earth, your spine, the crown of your head and up into the sky. This may not feel good at first, but eventually you will grow into it, believe it.

In standing meditation the vertical line may be visualized as life-force and raised upward through the heels and the crown from earth to sky. Gently reminding yourself to keep an erect spine throughout the day will also help your posture and meditation. Keep your pelvic muscles contracted and your abdomen firm when you stand and walk.

In public, this meditation may be done sitting, standing, walking, and generally going about one’s business, quite naturally.

Slow walking meditation, called kinhin in Zen Buddhism, is a natural complement to sitting meditation. It is usually practiced after or between meditation periods. The hands are held at the height of the solar plexus, shoulders relaxed, forearms parallel to the ground.

The left hand makes a fist with the thumb within the fingers. The right hand is open, palm covering the back of the left hand, with the thumb resting on top. When palms are facing the chest, this position is called shashu, when palms face the ground, it is called isshu.

The eyes look down at a forty-five degree angle. Walk clockwise around the room. Each foot steps only until the heel reaches as far as the midfoot of the other foot. Each step takes one full cycle of breath. These guidelines should be considered with the advice of a licensed health care provider such as a physical therapist or physician.

Hands and Gaze

Religions of Indian origin have developed many hand gestures over the course of time to use during meditation. A hand gesture is called a mudra. In yogic meditation one may keep the hands open with the palms facing up, resting on the knees, or touch the tip of the index finger with the tip of the thumb of each hand.

Daoists touch the tips of their thumbs together, the right thumb inside of the left hand, the left hand a fist inside the closed right hand. Chinese Chan practitioners have traditionally rested their thumbs upon their fingers and sat in meditation facing away from the wall. Japanese Zen practitioners arch their thumbs above the fingers, cradling the left fingers in the right fingers, forming a circle with the digits, and sit facing a wall.

The eyes remain about one-third of the way open and gaze slightly downward at about a forty-five degree angle. Although some forms of meditation practices may begin with attention focused on a visual aid, as a locus for concentration, just as some methods focus on the breath or visualization, in Illumination meditation the eyes do not settle on any object.

Of course, Illumination meditation does not aim to rest the attention within the senses or the imagination, and is in fact described as a “sloughing off of body-mind.” Illumination meditation is an end in itself; it is not a meditation practice with stages to enlightenment, but a ritual enactment embodying the awakened self. It is the central practice of a life of composure and comportment.

Mind

The benefits of meditation, like improved health and better performance in mental and physical endeavors, are peripheral to the point. The illumination of Illumination meditation is ultimately an end in itself whether performed alone or as a community.

Illumination meditation is not necessary to awakening to original nature, but its discipline of the mind can help create the right environment for it. Without illumined awareness, meditation is reduced to mere symbolic expression of enlightenment, or pure utility. Enlightenment, the realization of the truth of ultimate unity, is an escape from conditioning and the beginning of wisdom.

Zen Buddhist zazen is more than a method to seek enlightenment or cultivate health: it is the epitomical activity of the enlightened person. Such a person ideally remains in a meditative state all day, throughout all daily activities, and takes every opportunity to meditate, especially sitting meditation.

The very name “Buddha” means, “awakened one,” and enlightenment experiences are of penultimate value, but they are not the only reason to meditate. Even the most enlightened sage, like the Buddha, has to meditate, study the laws of nature, live morally, and go through the tedium of everyday life.

Mountains and Rivers

The founder of the largest Zen school, the Soto Zen sect, Eihei Dogen (a.k.a. Dogen Zenji, literally “Zen Master Dogen”), was a Japanese monk who studied meditation in both China and Japan in the early thirteenth century. Dogen wrote the Eihei Shingi, the first Buddhist monastic code in Japan. After critiquing the Chan method of meditation in the Zuochan Yi, part of the accepted rule for Chan Buddhist monasteries, Dogen penned the Fukanzazengi, or Universally Recommended Instructions for Meditation.

Where Samadhi is absorption in the Dao or Way, the Fukanzazengi says, “Concentrating single-mindedly is practicing the Way wholeheartedly. Thus your practice and realization are undefiled and manifested in your daily life.” Even the wisest mortals, enlightened or not, sit in Illumination meditation, not to achieve anything, but because it is the ultimate function of the awakened mind.

Dogen practiced a technique he learned from his Chinese teacher, called Shikantaza, “(nothing but) just sitting (in awareness),” or Silent Illumination. Dogen describes Shikantaza as a form of zazen which is not thinking, not concentration or meditation practice with several steps, but just sitting in the realization of complete enlightenment.

In this state, there is nothing more to add, nothing that needs to change. The state of awakening known as Samadhi, or Buddha nature, “manifests by itself through sitting silently.”[2]

This is the ultimate meditation, the culmination of all practices, and it is properly called Illumination meditation.

Practice with a Group

Of course, meditation should be learned directly from a qualified teacher, and it is normally beneficial to practice in some way with a community. Perhaps in the future I will be able to post suggestions here, but for the time being let it suffice to advise that you find your local Zen center or choose from one of the many groups that offer meditation via online video conferences.

Now, go sit on a cushion!

If you want to learn more about different kinds of meditation, you can start with the articles of the Science Abbey Meditation Guide series:

SCIENCE ABBEY MEDITATION GUIDE

I: Basic Meditation Manual

II: Buddhist Insight Meditation

NOTES