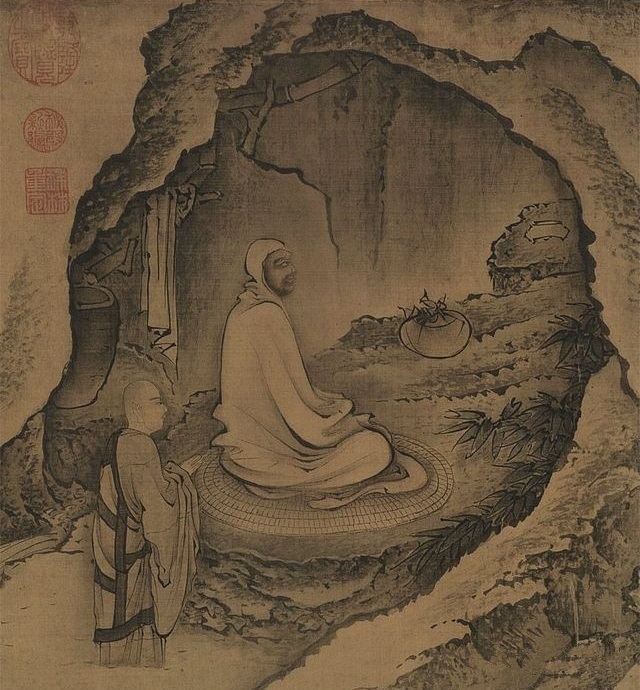

Zuo Chan, Sitting Meditation

The first Chinese people to become interested in Buddhism were Daoists. These Daoists became the first converts to Buddhism in China. Over the next couple of centuries Sanskrit Buddhist works on meditation, enlightenment and the path of the bodhisattva were translated into Chinese.

Chinese mystics adopted and adapted Buddhism to their needs, replacing the Indian focus on dharana, or concentration, with Daoist cultivation in meditation. This practice of sitting meditation, known as zuo chan, would eventually flower into Chan Buddhism.

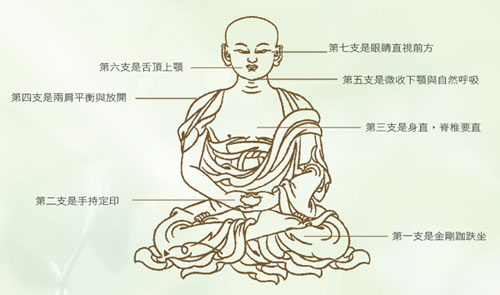

Chinese Buddhists practiced sitting meditation, or zuo chan, before the foundation of the Chan school. Learning the early Nikaya suttas, they meditated with the concepts of calm and insight (vipassana and samatha) using the Celestial Buddha (Vairocana) Seven-Points of Sitting with dhyana and samadhi, two levels of induced concentration. The seven points are as follows:

- Legs: sitting on a cushion, crossed in full lotus or half lotus

- Back: spine straight

- Shoulders: rested and spread apart

- Head and Neck: chin slightly lowered

- Hands: even; in the lap or on the knees in mudra

- Mouth: closed with tip of the tongue touching the palate

- Eyes: half open, gazing past the tip of the nose at a 45 degree angle

Zuo chan includes slow walking and fast walking between periods of sitting meditation. In slow walking the forearms are held parallel to the ground with the right fist held in the left hand. Fast walking is done with arms naturally at the sides. Attention is held on the bottom of the feet.

In sitting meditation, attention is first brought to the breath, which should be natural. Attention should also remain on the tip of the nose or the dantien, the body’s center of balance, about two inches below the navel. Sitting meditation may be done for 20 minutes or a half hour at a time.

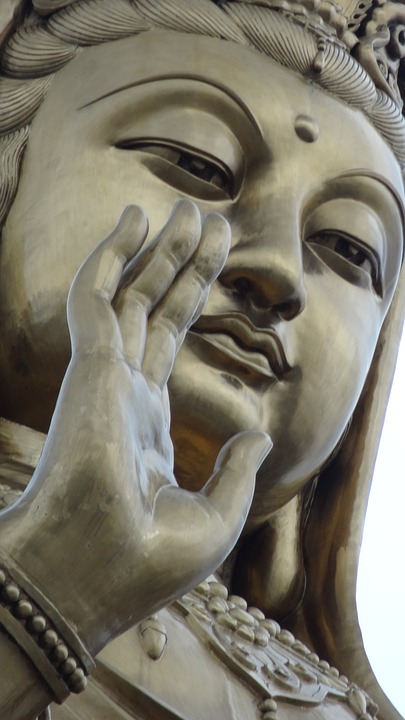

Vairocana is a celestial Buddha. In Chan, Zen and Soen he is the embodiment of emptiness, or oneness, who also represents the Dharma Body of Siddhartha Gautama, the historical Buddha. Vairocana is the central deity of Esoteric (Tantric) Buddhism. He is eternally seated in meditation postured in the full lotus position and he is portrayed using various mudras.

The Vairocana Mudra, or Dharma-realm Samadhi Mudra, is also known as the Cosmic Mudra, Dhyana Mudra or Meditation Mudra. The Cosmic Mudra rests the hands on top of the feet and below the navel. The left hand rests in the right hand, palms facing upward, with the tips of the thumbs touching.

This mudra is said to have been used by Siddhartha before he was enlightened under the Bodhi tree.

The Three Teachings

Various schools of Buddhism arose in China as different teachers from various monasteries brought their traditions from India. Indian yogic techniques centered on the concept of attaining enlightenment through cultivating prana (not to be confused with prajna, “transcendent wisdom”), the equivalent of Qi, or life-force.

Buddhism brought some of these Hindu yogic practices to China, where they may properly be termed Qigong. The Indian meditation called dhyana, literally, “meditation” or “contemplation,” became “chan” in China.

Daoism and Buddhism began a long history of syncretism as soon as Buddhism was introduced to China. Chinese words were often used to describe Buddhist concepts. Buddhists interpreted the Dao, or “Path,” as the Buddha’s Noble Eightfold Path and enlightenment.

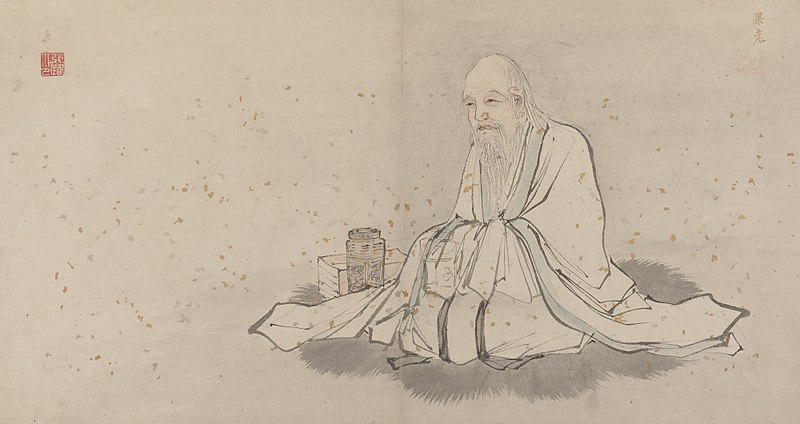

During the Han dynasty (fifth and sixth centuries) it was popularly claimed that when Laozi travelled West to teach the barbarians the Way, he became the Buddha. The famous ninth century Daoist Qingjing Jing, “Classic of Purity and Stillness,” of unknown authorship, combines Daoist guan, or observational meditation, and Buddhist Vipassana, or insight meditation.

The term “jingshe” originally referred to an ancestral hall used for sacrifice, but evolved to mean a Buddhist monastery, Daoist meditation chamber or Confucian study hall. The Han emperor Huan (c. 132–168) is recorded as offering sacrifices to the Yellow Emperor, Laozi and Buddha.[1]

Starting from the sixth century Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism were known as “the three teachings,” a single philosophy built on the mutual influence of these three traditions.

Where, tradition claims, Laozi wrote the Daode jing.

Influences on Religious Daoism

The “three teachings” were further fused into a single composite Chinese culture during the Tang dynasty (618 – 907 CE). This eclecticism was especially successful on the local level among the common people.

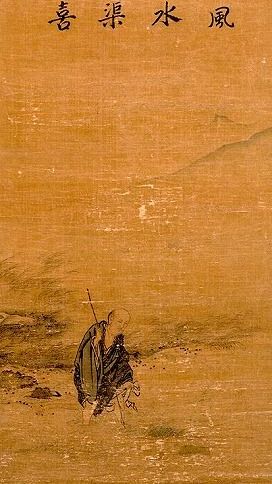

An excellent example of this is to be found in the poetry of Han Shan, an eighth century reclusive Buddhist monk who had studied the Confucian classics and wrote in both Daoist and Chan traditions. Daoist inner alchemy and Chan meditation, centering on individual cultivation, became the fashion among the elite.

Zhang Ling, a.k.a. Zhang Daoling (34 – 156 CE), was the founder of the Way of the Celestial Masters sect of Daoist religion. The founding of the Celestial Masters sect was followed by emergence of the Shangqing (Supreme Clarity or Great Purity, also known as the Mao Shan sect) and Lingbao (Sacred Jewel) traditions in the fourth and fifth centuries.

These latter two schools borrowed much from the competing religion of Buddhism, including the concept of rebirth and descriptions of heavens and deities. Lingbao, especially, adopted aspects of Buddhist doctrine, ecclesiastical hierarchy and ritual traditions.

The Daoist school of Quanzhen (the Way of Complete Perfection), founded in the twelfth century, is today with the Zhengyi sect, one of two extant Daoist schools. Returning to simple Daoist philosophy by trimming magical and religious elements, the Quanzhen movement owed much to Confucianism and relied heavily on Chan Buddhism for its meditation, ritual and monastic practices.

Due to its strict monasticism, the Quanzhen sect remains the predominant form of Daoism in China, today.

Daoist Buddhism

A few strictly sectarian Zen masters, like the founder of Soto, Eihei Dogen, condemned those who followed the three teachings or who studied Laozi and Zhuangzi along with Buddhism (see Dogen’s Shobogenzo, “Shoho Jisso”). Respected modern scholars generally recognize that Chan/Zen is the early marriage of Daoist philosophy and Buddhism.

Fung Yu-Lan claimed that Chan masters called enlightenment “the vision of Dao.”[2] A.C. Graham described Chan and Zen as the continuation of Daoist philosophy.[3]

According to legend, the Pure Rules of Baizhang was compiled in the eighth century as the first rule to sinicize the vinaya, the first comprehensive Chan code. The original rule was known only through quotations in later works and is now generally believed by scholars never to have actually existed.

However, in the next centuries, the Rule of the Chan Gate/Monastery (Chanmen guishi) claimed to be a synopsis of the code and was used extensively. In its very first words this code states that most people value the realization of the Way (Dao) above all else. Because of this, it is written, the rulers of China have revered the Buddha and treated Buddhists very well.

The Daoist Zhuang Zhou lived in the fourth century BCE. While the first seven chapters, the “inner chapters,” of the Zhuangzi were likely written by him, the other writings attributed to him were composed over the next 200 years. The fourth century philosopher Guo Xiang put together the popular 33 chapter Zhuangzi known today.

The Chinese Buddhist monk and philosopher Zhidun (314-366) was the first Buddhist to address the Zhuangzi. His interpretations followed the style of xuanxue, or “Dark Learning,” a school of Confucian-influenced Neo-Daoism.[4]

Mouzi was a second century Confucian scholar and official who studied the Confucian Classics, the Laozi and Buddhist literature. He converted to Buddhism and the Buddhist apologetic and hermeneutic book of dialogues, Mouzi On the Removal of Doubt (Mouzi Lihoulun), is attributed to him. The Maozi Lihoulun was incorporated into the Chinese Buddhist Canon.

Defending Indian Buddhism from criticisms born of Chinese culture, and critical of the Daoist concept of immortality, Mouzi often described Buddhism in Daoist terms. To Maozi, Buddhism was Fudao, the “Way of Buddha.”

Daoist Influence on Chinese Buddhism

Kumarajiva was a fifth century Indian Mahayana Buddhist monk and translator of sutras. He was born in Kucha, present day Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in China, and died in Chang’an, present day Xi’an. Kumarajiva had a very interesting life.

Earning fame due to his debating prowess, he was ordained in a palace and was later brought to Chang-an, the capital at the time, by Emperor Yao Jing, with whom he helped spread Buddhism throughout China.

Kumarajiva used Daoist terminology in his descriptions of Buddhist philosophy, such as yu, “being,” wu, “non-being,” and wu-wei, “non-action.” A distinctly Chinese form of Buddhism was developing within schools, which incorporated Daoist concepts and would later become Chan Buddhism, distinguishing these schools from schools of Indian Buddhism in China.

Kumarajiva’s first translation was the Sutra on the Concentration of Sitting Meditation, the first Buddhist meditation manual available in China.[5]

At least two of Kumarajiva’s foremost disciples studied Daoist works like the Laozi and Zhuangzi, and reinterpreted Daoist concepts in a Buddhist context. The Buddhist monk Daosheng (c. 360–434) stayed in Chang’an with Kumarajiva and helped the master translate the Lotus Sutra.

Daosheng was influential in spreading the idea that all beings have Buddha-nature. His commentaries on the Lotus Sutra, Vimalakirti Sutra and Astasahasrika-prajnaparamita Sutra made him one of the foremost scholars of the Six Dynasties era (220-589 CE).

Sengzhao (c. 384-414 C.E.), a dissatisfied student of the Laozi and Zhuangzi, studied the Vimalakrti Sutra and was inspired to become a Buddhist monk. Sengzhao assisted Kumarajiva with translations and authored The Treatise of Sengzhao (Zhao lun), elucidating Nagarjuna’s ideas of emptiness (oneness) and the meaning of prajñāpāramitā, the perfection of wisdom. Through early Chinese Buddhist philosophers like these, Daoist philosophy came to have a lasting influence on Chan Buddhism.

The great compilation of Chan biographies known as the Transmission of the Lamp lists Mazu Daoyi (709-788) as a disciple of Nanyue Huairang (677-744), traditionally the principle disciple of Dajian Huineng, sixth Patriarch of Chan. Nanyue’s relationship to Huineng may have been invented to connect Mazu with this lineage when his Hongzhou school brought in the golden age of Chan during the Tang dynasty.

The sixth century Biographies of Eminent Monks (Guzunsu yulu) has Mazu give a sermon on the Dao wherein he advises to meditate on emptiness and enter into Samadhi.[6] In “The Mind is Buddha” in the Transmission of the Lamp a student asks Mazu a series of questions, leading to “If you met a person who was free from all attachments, what would you say to him?”

Mazu replies, “I would let him experience the Great Dao.”

While Caodong and Soto are descended from Shitou Xiqian (700-790), the Linji (Japanese Rinzai) school is descended from Mazu. Mazu’s Extensive Records contains the first ever recorded use of the term, “Chan school.”

Chan Buddhism

Scholars assign different periods to the development of Chan Buddhism. The time from Bodhidharma in the late fifth century to the late eighth century Tang Dynasty is the era of the first patriarchs of Chan. Chan thrived and reached its literary summit during the Tang Dynasty, the cosmopolitan golden age of Chinese civilization. The great masters of Chan arose from the eighth century to the Song Dynasty (960 – 1279).

The essential teachings of Chan begin with Gautama Buddha. The Buddha’s disciple Mahakasyapa of Magadha was enlightened when Buddha held up a white flower during his wordless “Flower Sermon.” Mahakasyapa smiled and was thus chosen to follow Buddha as head of the Sangha. The Chan school calls this wordless transmission of Buddha’s teaching of enlightenment the “mind-seal.” This is how the Buddhist lineage began.

The lineage proceeded through its patriarchs to Bodhidharma, the twenty-eighth Indian patriarch from Gautama Buddha and the first patriarch of Chinese Chan Buddhism.

Bodhidharma migrated to China sometime between the period of the Northern and Southern dynasties and the early Tang dynasty, that is, between the fifth and seventh centuries of the Christian Era. As the founder of Chan Buddhism, Bodhidharma was also credited with teaching boxing at Shaolin temple and introducing tea consumption to China as a stimulant for monks during zuochan.

According to tradition, Bodhidharma meditated facing the wall of a cave for nine years. Bodhidharma is said to have authored his short Outline of Practice, where he muses that one enters the Path (the Dao) by reason, meaning meditation (the Daoist wu-wei, “non-doing”), or otherwise by special practice. He names four essential practices: suffering injustice patiently, detached adaptation to the world, cessation of seeking or seeking nothing (wu), and practicing virtue (the Dharma), especially charity.

The legend of Dazu Huike asserts that Huike convinced Bodhidharma to accept him as a student by standing in the snow outside of Bodhidharma’s cave and severing his own arm to prove his devotion. According to Huike’s biography by Daoxin, Bodhidharma gave Huike the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra as his main scripture. Huike taught a form of one-step meditation he called biguan, “wall gazing” or “wall contemplation.”

Bodhidharma and his disciple Huike lived as wandering ascetics, as did their followers. Jianzhi Sengcan (died 606 CE) was the Third Patriarch of Chan and the probably pseudonymous author of the Xinxin Ming, “Trust in Mind” or “True Mind,” the first written declaration of the Chan school of Buddhism. Huike gave him the name Sengcan, which means, “Gem Monk.”

Dayi Daoxin (580 – 651) was enlightened by Sengcan, who bid him spread the Dharma in the North when the Patriarch migrated to the South to teach the Dharma there. As the Fourth Patriarch of Chan, Daoxin established the first Chan Buddhist monastic community and taught meditation.[7]

Jìngjué’s (683 – c. 750) Lengqie shizi ji, the Record of the Masters and Disciples of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, contains a version of the Treatise on the Two Entrances and Four Practices (Erru sixing lun), attributed to Bodhidharma, with a preface by Tánlín (506–574), a disciple of Bodhidharma or Huike.

This treatise is the first written record of Bodhidharma’s teachings, introducing his doctrines of non-duality, emptiness and inherent Buddha nature. A passage in the Lengqie shizi ji, attributed to Daoxin, may be the first account of Chan meditation technique.[8]

Mindfulness of Breathing

Ānāpānasati (Sanskrit: ānāpānasmṛti), “Mindfulness of Breathing” is recorded in several suttas as the method of meditation taught by Gautama Buddha. The foremost of such texts is the Mindfulness of Breathing Discourse (Pali: Ānāpānasati Sutta, Sanskrit: Ānāpānasmṛti Sūtra), one of the 152 suttas in the Majjhima Nikaya.

Composed between the third century BCE and second century CE, the Majjhima Nikaya is one of the five collections in the Sutta Pitaka, the second of the three books of the Pali Tipitaka, the Theravada Buddhist Canon.

The Ānāpānasati Sutta alleges to be the Buddha’s teachings on meditation. Anapana is the observation of the natural breath. Sitting in silence and stillness, one is mindful of the entire body, while awareness is concentrated on inhalation and exhalation. Meditation is undertaken for the purpose of experiencing seven successive stages of enlightenment: mindfulness (sati), analysis (dhamma vicaya), enthusiasm (viriya), ecstasy (pīti), tranquility (passaddhi), trance (samadhi) and finally equanimity (upekkhā).

Anapanasati underlies the teaching of satipatthana, the “foundation of mindfulness,” four domains of mindfulness (physical body, senses, mind and phenomena), each further divided into four stages, for a total of sixteen steps of meditation.

Along with the Ānāpānasati Sutta, the Discourse on the Establishing of Mindfulness (Satipatṭhāna Sutta) and The Great Discourse on the Establishing of Mindfulness (Mahāsatipatṭhāna Sutta) form the foundation of Theravada Vipassana meditation.

Similar sutras exist in the agamas (scriptures) in the Chinese and Tibetan canons, which are referred to as Tripitaka even though they are not divided into three books.

The Buddha instructs to sit beneath a tree in a forest and observe the breath, recognizing when the breath is either long or short. It will be noticed that this core Buddhist breathing and mindfulness meditation (anapanasati) in tranquility (samatha) and emptiness (sunyata) are reminiscent of the Daoist philosophies and practices of Laozi and Zhuangzi.

Chinese Buddhists practicing this kind of meditation developed the philosophies and methods of the Yogacara and Tiantai schools, as well as the school of Chan, the most successful form of Buddhism in China.

Early Chan Meditation

A Parthian prince turned Nikaya Buddhist monk named An Shigao (c. 148-180 CE) was one of the first Buddhist missionaries to China. He was the first to translate texts on meditation with instructions on counting breaths to enter into the concentration of mindfulness meditation, namely, the very influential Scripture of Mindfulness of Breathing (Anapanasati Sutta) and the Discourse on the Establishing of Mindfulness (Satipatthana Sutta).

The Buddhist monk Lokakṣema (c. 147/164-186/189 CE) was born in the ancient Indo-Aryan kingdom of Gandhāra. Gandara was located in Central Asia in what is present day north Pakistan and north Afghanistan, then a part of India. The kingdom was a center of Zoroastrianism and Greco-Buddhism. Lokaksema translated the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra and other Mahayana sutras, concentrating on asceticism, meditation and Samadhi.

Fotudeng (c. 232–348 CE) was a missionary Buddhist monk from the Buddhist kingdom of Kucha in present day Xinjiang, China. He studied in Kashmir, India before going to Luoyang and converting Chinese warlords to Buddhism. As court chaplain under Shi Hu (295–349), Emperor Wu of Zhao, he helped found some 900 Buddhist temples and monasteries while his influence occasioned mass conversions.

Fotudeng taught meditation, chiefly ānāpānasmṛti or “mindfulness of breathing,” counting the breaths and concentrating to enter Samadhi.

Some of Fotudeng’s disciples went on to assist Kumarajiva in his labors, and one of his most famous disciples was the monk Dao’an (312–385). Dao’an wrote commentaries, translated and supervised the translation of Buddhist scriptures into Chinese, compiled scriptures into a catalogue, and even developed his own code for his monastic community in the capital.

Dao’an and his disciple Huiyuan (334–416) were advocates of ānāpānasmṛti and buddhānusmṛti; mindfulness of Buddha, or meditation on Gautama Buddha or other Buddhas or Bodhisattvas.

Gautama’s directions for meditation were passed on orally for centuries before Buddhist monks wrote down instructions attributed to the Buddha. It cannot be known what exactly Siddhartha taught. The methods passed down to posterity are relatively vague and unstructured, but the efforts of Buddhists down through the ages have produced detailed instructions and explanations. Tradition has even developed rigorous annual retreats and daily scheduled meditations for those who take monastic vows.

Scheduled Meditation in Daoism, Buddhism and Christianity

Daoist hermits existed even before Zhuangzi in the third century BCE and formal Daoist religious organization, including the first monasteries, began with the Celestial Masters sect in the second century CE. Over the next few centuries, Daoist monastic organization and daily routine arose, usually following the Buddhist example.

The earliest Daoist rules were the Tang Dynasty Rules and Precepts for Worshipping the Dao (Fengdao kejie) and the Scripture of Karmic Retribution (Yinyuan jing).[9] From these it is clear that Daoist monks practiced silent mindfulness meditation, as well as visualization, as part of regular scripture reading ritual.[10]

In the third century BCE the Christian Desert Fathers in the Egyptian desert began building monastic communities. These ascetics held regular communal scripture recitation and prayer to complement solitary practice. Lectio Divina, “divine reading,” was developed by Benedict of Nursia and Pope Gregory I in the sixth century CE as a system of reading scripture and prayer.

The Rule of Saint Benedict established a structured schedule including specific times for sole and communal Lectio Divina, known as the Liturgy of the Hours, the Divine Office or the Breviary. Lectio Divina was further formalized by a monk and prior of the Carthusian Order, named Guigo II, in the twelfth century as four-stage process (lectio, meditatio, oratio, and contemplatio), which incorporated silent meditation.

The earliest Buddhist monastic code was mostly compiled in India soon after the death of Gautama Buddha. As such, it is the oldest of the three sections of the Buddhist Canon, the Tipitaka, or Three Baskets.

The code is still extant as the Theravadin Book of Discipline, or Vinaya Pitaka, and consists of three books: the Rule Analysis (Suttavibhanga), the Collections (Khandakas) and Accessories (Parivāra). It includes directions for virtuous behavior, dress, meals, lodging, ceremonies, and dispute resolution, and consequences for breaking the rules.

Meditation was taught in the Dhammapada and certain sutras in the Tipitaka, but the Indian monastic rule, or vinaya, does not provide instruction for meditation or establish a meditation schedule.

Over twelve hundred years from the time of Gautama Buddha, around the time of Bodhidharma (fourth-fifth century), the earliest Chinese Buddhist monastic codes began to form, and included regular meditation schedules for monks. At the same time, the first records of Chan seated meditation were written, attributed to Bodhidharma and his disciple Huike.

Scheduled Meditation in Chan and Zen

The Chinese monk Daoan (312-385) stands out not just for his translations, catalogue and commentaries, but also for his early formation of a sangha and disciplinary code for his monastic community. Elements of his no longer extant code, Standards for the Clergy and a Charter for Buddhism (Sengni guifan fofa xianzhang), have been put into practice up to the present day.[11]

Daoan influenced Kamarajiva in regards translations and Daoxuan in regards vinaya. Daoxuan (596-667) was the most prominent Lü tradition monk. He is best known for his history and commentary of vinaya in his Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks, a work that had a profound impact on later Chan rules. In the Lizhi fa shitiao (Rules in Ten Clauses), Zhiyi (538-597) directed monks specializing in meditation to devote four periods of time to it daily.[12]

The first vinaya to be translated into Chinese was the Ten Recitation Vinaya (Sarvastivada Vinaya) of the Sarvastivada school, translated by Kamarajiva in the fourth century. The Four-Part Vinaya (Caturvargika Vinaya or Sìfēn Lǜ) of the Dharmaguptaka school, the rule still used today by Chan Buddhists, was translated in the fourth century by the monk Buddhayaśas of Kashmir.

The Five-Part Vinaya (Mahîùâsaka Vinaya or Wufeng lü) and the vinaya of the Kāśyapīya sect were translated in the early fifth century. Daoxuan discussed these vinaya and recorded that the Chinese knew of, but had not yet translated, the vinaya of the Pudgalavāda (Vātsīputrīya) school.[13]

Baizhang Huaihai (720–814) was the dharma heir of Mazu Daoyi and teacher of Huángbò Xīyùn, the teacher of Linji Yixuan, founder of the Linji (Rinzai) school. According to legend, Baizhang authored the Pure Rules of Baizhang, the first rule to sinicize the vinaya and the first comprehensive Chan code.

The original rule of Baizhang was known only through quotations in later works and is now generally believed by scholars to have never actually existed. The tradition of the rule greatly influenced future Chan and Zen “Rules of Purity.” It famously encouraged self-sustaining farming at monasteries with the phrase “A day without work is a day without food.”

However, Baizhang’s instruction was not the landmark accorded it by legend, as Guishan’s Admonitions (Guishan jingce), by Baizhang’s disciple Guishan Lingyou (771–853), the senior founder of the Guiyang school, shows that Chan practice remained well within established Buddhist monastic tradition. This is also borne out by the earliest extant Chan code, the Teacher’s Regulations (Shi guizhi), written by Xuefeng Yicun (822–908) in 901.[14]

There is no mention of meditation periods in the ninth or tenth century Rule of the Chan Gate/Monastery (Chanmen guishi), which claims to be a synopsis of the Baizhang regulations. This rule was published as “Regulations of the Chan Approach” with the biography of Baizhang in the Record of the Transmission of the Lamp (1004). A full version was also in the Chanyuan Qinggui as “A Commentary on the Baizhang Rules” (1103) and included as a preface in the Imperial Edition of the Baizhang Code (1336) during the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368).[15]

The Rules of Purity in the Chan Monastery, the Chanyuan Qinggui, was compiled by Changlu Zongze (died c. 1107) in 1103. Also known as the Monastic Regulations of the Zen Garden, this monastic code was previously considered to be the earliest extant Chan monastic code. It is not certain when scheduled silent meditation began for Chan Buddhist monks, but it was certainly standard practice by the time of the composition of the Chanyuan Qinggui, where there are references to daily morning and evening meditation periods in the practice hall.

In the Southern Song dynasty (1127-1279) Chan monasteries began holding meditation periods daily at regular hours at four times: dawn, dusk, late evening and midnight.[16] These became known as the “four hours,” and were used in China and Japan until about the fourteenth century, when three hours became the norm. Besides daily communal meditation sessions, Buddhist monastics gather together for special weekly, monthly and annual intensive meditation periods.

From the time of Shakyamuni Buddha, the Indian Buddhist monastic community of wandering mendicants would gather together during the rainy season, a period of about three months. The Vinaya code forbade travel during this time, about ninety days between the middle of the fourth and seventh lunar months, approximately April through July. Since Dogen’s time, Japanese Zen has utilized this period as an intensive summer retreat called Ango, literally, “peaceful dwelling.”

The annual retreat is a requirement for Soto Zen Buddhist monks. Anyone can do Illumination meditation alone, but the monastery is the ideal place to teach and practice Buddhist discipline (vinaya), including ethics (sila), and meditation (dhyana and samadhi). Meditation is the ideal way to cultivate wisdom, which in Buddhist tradition is known as prajna; the wisdom that abides in a boundlessness beyond duality. This wisdom depends only on insight into the empty or illusory nature of all mental constructs, such as awareness, thought, feeling and perception.

The Chan Philosophy of Void

The Prajnaparamita sutras are largely based on the philosophy of emptiness or void and bodhisattvas developed by the Indian philosopher Nagarjuna (150 – 250 CE). Prajnaparamita refers to transcendent wisdom, the goddess that embodies this wisdom, and a body of about forty early Indian sutras composed between 100 BCE and 600 CE. The Prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya, “Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom,” known as the Heart Sutra, is the most widely known Mahayana scripture.

The Heart Sutra is a very short poem, when translated from the original Sanskrit, about 260 Chinese characters. The poem is mainly based on the much longer Prajnaparamita sutras. It was written from the second to the fourth century CE, translated into standard Chinese form by the renowned traveller, writer and translator Xuanzang (c. 602-664 CE), and is today recited by many schools of Buddhism throughout Asia, including Chan and Zen schools.

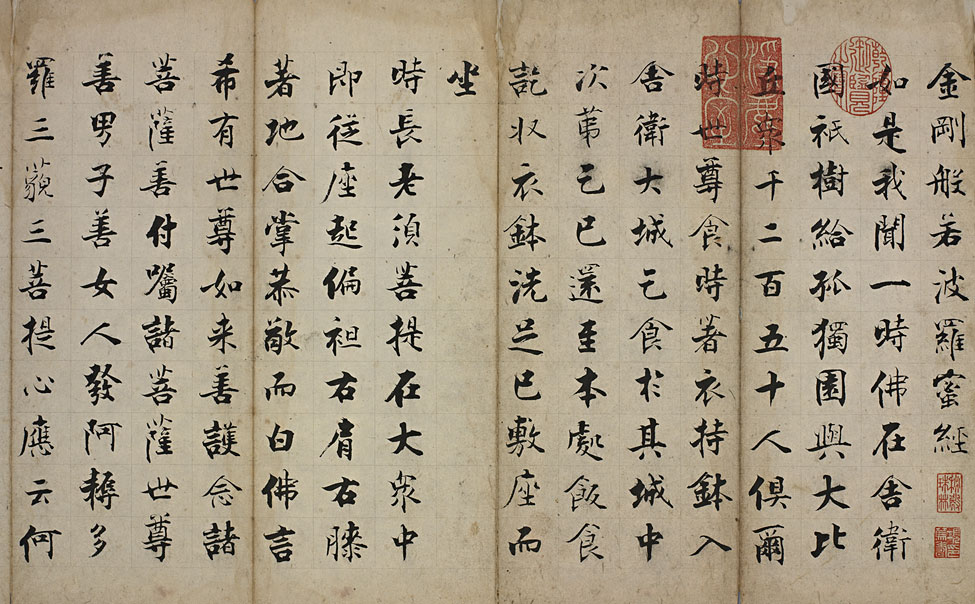

Transcendent wisdom, or prajna, is the insight into reality that realizes that all is void, impermanent, and suffering. The Diamond Sutra, or Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra (The Diamond That Cuts Through Illusions) in Sanskrit, printed in 868 CE, is the oldest known printed book in the world.[17] [18] By tradition it was written by the legendary Indian alchemist Nagarjuna, the fourteenth patriarch of Chan Buddhism and first teacher of void, but its real authors remain unknown.

The Diamond Sutra’s doctrine of the void (prajna) interprets “voidness,” or emptiness, as a state of mind and of being. Although their understanding of Daoist meditation is suspect, some advocates of this doctrine criticized the no-mind of the Daojia (Daoist philosophers), what they claimed was the method of just sitting, as worthless quietism. Their certainly valid point was that there is more to meditation than just quieting the mind. There is illumination in the tranquility.

The unknown authors of the Diamond Sutra insisted on the importance of concentration of awareness for the cultivation of insight into the void, the emptiness or oneness of reality. Paradoxically, this illumination occurs only within complete stillness, silence and cessation of effort. It is pure observation. This is just prajna as dhyana and Samadhi. The Sutra of Huineng reinforces this doctrine in the second chapter, “On Prajna,” after the first chapter presents Huineng’s autobiography.

Huineng and the Caodong School

Huineng (638-713) was the founder of the Southern School and Sixth Patriarch of Chan Buddhism, and is a central figure in the history of Chan and Zen Buddhism. His teacher, Daman Hongren (601-674 CE) trained with the Fourth Patriarch Daoxin from childhood and was made the Fifth Patriarch of Chan Buddhism. Hongren’s teachings were collected into the Treatise on the Essentials of Cultivating the Mind, the first collection of any Chan teacher’s ideas.

Huineng’s Dharma successor, Heze Shenhui (684-758) initiated the division of Chan into what he called the gradualist “Northern School” and the sudden enlightenment “Southern School,” inventing this story to slander rival Shenxiu’s school as gradualist. Some scholars doubt that Shenxiu even took a gradualist approach. It is theorized that Huineng’s successor Shenhui fabricated the idea of a single lineage of Patriarchs to establish his intolerant political positioning as historical fact.

Shenhui’s ultimate goal was to impress the imperial court and gain political influence. His claims that the Diamond Sutra was Bodhidharma’s primary guide, rather than the Lankavatara Sutra, are also suspected to be propaganda. Nevertheless, these teachings are important to the Chan and Zen lineages. Shenhui probably also concocted the famous Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch, otherwise known as The Sutra of Huineng, credited to Huineng’s disciple Fahai.

Historically, once formed, the Northern and Southern schools both immediately received support from royalty and aristocracy. Various lineages branched off from the two schools, which became known as the Five Houses of Chan: Guiyang, Linji, Caodong, Yunmen and Fayan. Dongshan Liangjie (807-869) was the founder of the Caodong school of Chan Buddhism.

Today Chan monks still revere Dongshan as the most influential figure of their school. Dongshan’s short poem called Five Ranks is foundational to Caodong philosophy. His foremost disciple and Dharma heir was Caoshan Benji (840-901). The name “Caodong” is derived by combining the first syllables of the names Caoshan and Dongshan. In Japanese their names are Sozan (Caoshan) and Tozan (Dongshan); and their school is known as the Soto Zen school.

The Caodong school focused on sitting meditation and Silent Illumination. After the fall of the Tang dynasty (618-907 CE), Chan came into its own as the predominant form of Chinese Buddhism, with several competing schools arising from geography and slightly different approaches. The Linji and Caodong schools are the two main branches of Chan in China today, as well as in Japan, where they are known as Rinzai and Soto Zen schools, respectively.

Chan Silent Illumination

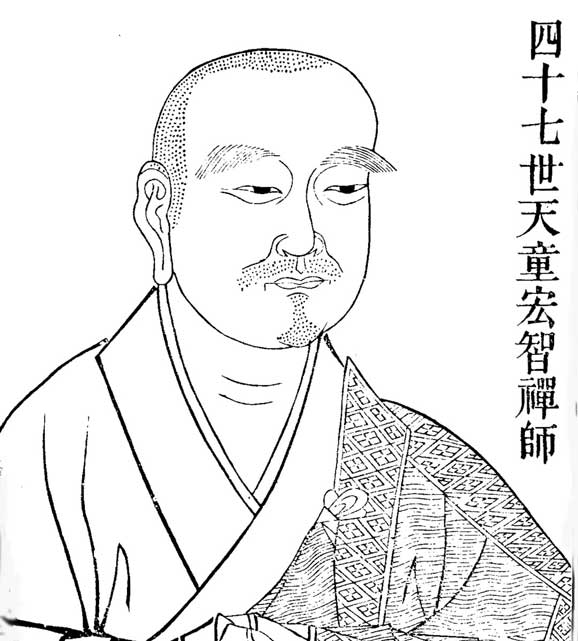

Hongzhi Zhengjue (1091-1157), a Chan Buddhist monk and abbot of Qìngdé Temple, was highly influential in his advocacy of mozhao Chan (Japanese “mokusho zen”), “Silent Illumination.” His Book of Equanimity became a central text of the Caodong school, as this and his other works established Silent Illumination as a predominant method of Chan meditation. It implies simply sitting in silence to return to the state of Buddhahood inherent in everyone.

Silent Illumination is the state of awakening to this ultimate reality, the direct realization of reality. Buddhist meditation is based on the principles of calm and insight (samatha and vipassana), equivalent to silence and illumination. Concentration (dharana) in meditation (dhyana) leads to absorption (samadhi).

In samadhi, one rests in transcendent wisdom (prajna), emptiness or void, which is known as illumination. The true nature of the mind is emptiness, as the true nature of reality is emptiness, wherein all is One, and sitting in silence with concentration allows the mind to observe this essential nature.

The Linji school criticized this method as lacking any breakthrough moment, and promoted instead, especially under Dahui Zonggao (1089-1163), kanhua Chan, “investigating a topic of inquiry.” This developed from the study of gong’an, “public cases,” of Chan masters, such as those recorded in the Blue Cliff Records by Dahui’s teacher Yuanwu Keqin. This technique was popularized in Japan by Hakuin Ekaku (1686-1768) and his disciples through the Rinzai Zen tradition as kannazen, the training in paradoxical riddles called kōans.

Hongzhi’s Silent Illumination was a primary influence on shikantaza, the meditation taught by Eihei Dogen, the founder of Japanese Soto Zen. Dogen visited China for several years to study Caodong Chan Buddhism. He received his Dharma transmission from the abbot Tiantong Rujing (Japanese: Tendo Nyojo) (1162-1228), at Qìngdé Temple on Tiantong Mountain, where Hongzhi Zhengjue had recently been abbot. In 1227 Dogen returned to Japan to found the Soto sect and teach at Kennin-ji Temple in Kyoto.

Chan Meditation

The Dharma Drum lineage of Chan Buddhism founded by renowned Master Sheng Yen (1931-2009) has its headquarters in Taiwan and has centers all around the world. It teaches a form of Silent Illumination meditation, which will only be summarized here from the perspective of a novice participant.

Those interested in learning Chan meditation are advised to visit a Dharma Drum center or other Chan lineage, like the Dharma Realm Buddhist Association, for a genuine introduction.

Meditation begins and ends with prostrations to an image of Buddha on a front altar. A warm up exercise, a mixture of muscular stretching and calisthenics, is followed by some self-massage. One sits upon the center of a mat and on the first third of a cushion, using a towel if necessary under the cushion and/or under a floating knee. A towel covers the legs to ward off wind. It is best to have a comfortable natural temperature, but one can use a fan, or even air conditioning, as long as the wind is directed away from people.

One assumes the meditation posture with the seven points and the Dharma Mudra, thumbs arching above the fingers to make a circle. The thumbs can rest on the hands when tired, or the thumbs can draw small circles for energy, but ideally they form a circle with the fingers.

In theory, Qi, or life-force, circulates in three circles: within the head, the body and the hands. The body then rocks back and forth, side to side, and then circles at the waist in both directions.

Three knocks of a wooden mallet on a wooden block announce the commencement of sitting meditation. One may purposefully relax the body and mind; starting with the top of the head, move down in sequence to the eyes, face, neck, shoulders, upper arms, lower arms, hands, fingers, chest, abdomen, upper back, lower back, waist, hips, upper legs, lower legs, and finally, the feet.

Be aware of the breath around the nose. One can count the breaths to ten every time one needs to refocus.

Two taps on a stick and one knock on the attached bell indicate the end of the meditation period. Stretching, self massage and prostrations conclude the activity. Again, this is just a brief description of modern Chan meditation, and anyone wishing to learn this tradition must seek a qualified teacher.

To read more about Buddhist meditation, Japanese Zen meditation and scientific mindfulness meditation, read the other articles in the Science Abbey Meditation Guide series:

SCIENCE ABBEY MEDITATION GUIDE

I: Basic Meditation: Meditation Manual

II: Buddhist Insight Meditation

III: Chinese Chan

NOTES