Origins

Mindfulness meditation may be defined as nonjudgmental awareness through purposeful holding of attention, being in the moment, for mental and physical health, self-knowledge and wisdom. One does not need to sit to be mindful; one can be mindful during all activities throughout the day. Along with its merit as a basis of insight, mindfulness is a form of therapy used in medical facilities around the world, and is scientifically proven to provide powerful benefits that change lives.

Although mindfulness may be comparable with Buddhist meditations like vipassana, zuo chan and shikantaza, it should be considered that the Buddhist techniques depend upon a whole system of philosophy, vows and way of life. This context of discipline, study, compassion and enlightenment supports meditation as the central function of a lifestyle and may produce fundamentally different results from those experienced through meditation unsupported by such infrastructure.

Mindfulness meditation arose from traditional Buddhist practices and the branch of medical science called psychology. It was originally popularized through Jon Kabat-Zinn’s Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center in 1979. Jon Kabat-Zinn (born 1944) studied Buddhist meditation with Vietnamese Thiền (Zen) monk Thich Nhat Hanh, Korean Seon (Zen) Patriarch Seungsahn Haengwon, and others. He adapted it, along with Hatha yoga techniques, to a secular scientific worldview. The result gave rise to what is popularly termed “mindfulness meditation.”

Jon Kabat-Zinn

Whereas MBSR is utilized to treat chronic pain, anxiety and other disorders, Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) was developed as a cognitive behavioral therapy to aid sufferers of clinical depression.[1] [2] [3] The science of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy is based on methods of cognitive behavioral therapy used in psychotherapy. The method was described in Kabat-Zinn’s book, Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness (Delta, 1991).

Kabat-Zinn has taught meditation to people from all walks of life, from CEOs and Olympic athletes to government staff and ecclesiastics. Mindfulness programs have been adopted by such diverse bodies as educational organizations, Fortune 500 companies and the United States Armed Forces. The mindfulness meditation program has been adopted by medical facilities throughout the United States and around the world.

A short introduction to mindfulness by Jon Kabat-Zinn, “Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Context: Past, Present, and Future,” was published by Oxford University Press in 2003 in the journal Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. Scientific research shows the positive benefits of these therapies and indicates promising conclusions in future studies. Not enough clinical research has been carried out to date to offer a full understanding of mindfulness.

The Science of Meditation

Scientific studies over the last sixty years have revealed many benefits of meditation, including pain reduction, increased immunity, improved memory, creativity and focus. Meditation decreases inflammation, depression, anxiety and stress.[4] Meditation can boost confidence, aid emotional regulation and promote social connection. Meditation causes certain short-term changes to the brain, including enhanced physical discipline, tolerance for discomfort, relaxation, concentration, and emotional intelligence.[5]

Modern science has shown that meditation can induce feelings of comfort and bliss, and make one more aware of oneself and the environment, as well as benefit emotional well-being and mental health in general.[6] [7] [8] Diffusion tensor imaging, or DTI, has shown that meditation also causes long-term changes in the brain, with effects throughout the whole brain. Meditation strengthens connections between the regions of the brain and slows brain atrophy caused by natural aging.[9]

Studies

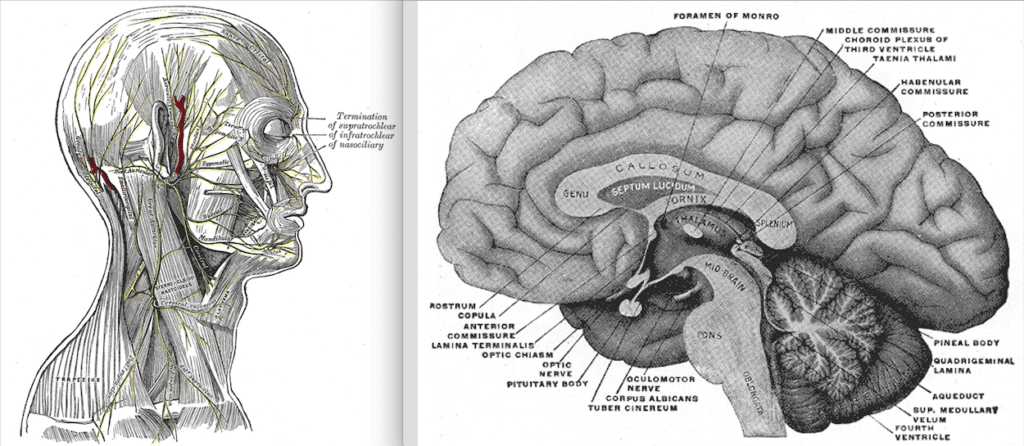

Studies on meditation and yoga include information from Positron Emission Tomography (PET), Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Single Photon Emission Computerized Tomography (SPECT) and electromyography, which show the many benefits meditation bestows upon the brain.[10] [11] Meditation increases frontal lobe activity such as attention, inhibition, judgment, planning, and voluntary movement. Some forms of meditation also may induce transient hypofrontality, a term that means the prefrontal cortex takes a rest and allows for a more holistic consciousness, like the runner’s high.[12]

Rael Cahn and John Polich published admirable tables in the Psychological Bulletin 2006 Vol. 132 No. 2, in “Meditation States and Traits, EEG, ERP and Neuroimaging Studies” (2006), which showed the various results of available neuroimaging studies on meditation from 1957 to 2005.[13] Studies included Yoga meditation, Transcendental Meditation, Kundalini Yoga, Tibetan meditation, Qigong, Zen, mindfulness meditation, self-hypnosis, meditation on the Psalms, Franciscan prayer, and others.

Researchers at W.M. Keck Laboratory for Functional Brain Imaging and Behavior, Medical College of Wisconsin, University of Wisconsin found using functional MRI that long-term concentration meditation changed the brain such that attention and response inhibition (self control) become empowered during meditation, while thoughts and emotions are increasingly suppressed with less effort (2007).[14]

B. Newberg and J. Iversen compared studies on neurochemical changes during yogic and Tibetan meditation in 2003.[15] Along with changes in brain activity, their findings also revealed increases in chemical neurotransmitters and hormones with positive effects, such as dopamine (reward and motivation), serotonin (well-being and happiness) and melatonin (sleep).

The Dalai Lama recruited Tibetan Buddhist monks for studies at the Waisman Laboratory for Brain Imaging and Behavior, University of Wisconsin-Madison. The findings, published in 2008, supported evidence of increased ease of holding attention and emotional self control associated with long-term practice of concentration meditation. The conclusion is that concentration is trainable and enhanced by meditation.[16] These findings bode well for those who, like Buddhist monks, are inclined to value meditation’s function as the embodiment of discipline, compassion, wisdom and enlightenment.

The Science of Illumination

Most scientific studies of meditation focus on its physical and psychological health benefits, ignoring its utility as a tool of observation or insight, and dismissing claims of enlightenment as the highest or ultimate psychological state of being. This is due to a general ignorance concerning the nature of enlightenment as higher consciousness. Scientific studies show that a vision of the universe as a oneness is not just good for the observer; it is objectively valuable to society.[17] Furthermore, scientific evidence supports this enlightened view of the universe as fact. Highly respected scientists have developed cosmological theories based on the evidence.[18]

The cerebral cortex in the brain processes the higher functions, like awareness, perception, memory and thought. Consciousness is the state of being awake (aroused) and aware. It is an elusive process about which there are many theories, but Harvard scientists may have located it as an interaction of three parts of the brain.[19] [20] [21] [22] [23] In simplified terms, the brainstem produces basic arousal, and two areas within the cerebrum, or cortex, produce awareness. Science shows that meditation increases brain function and enhances consciousness with a greater awareness.

Vinod D. Deshmukh asserts that neuroscience can help explain the yogic meditation of dhyana (zuo chan, zazen), Samadhi and enlightenment. He describes meditation as either total engagement, i.e., mindfulness, or total disengagement, i.e., silence and emptiness. The common outcome is self-understanding, well-being, happiness and knowing the meaning of life.[24]

The Revised Mystical Experiences Questionnaire was designed to gather information about mystical experiences caused by forms of meditation.[25] Participants in the study most experienced the categories of Positive Mood, Ineffability, Transcendence, and Mystical Experiences. Other experiences included “feelings of peace and tranquility,” a feeling of an encounter with “ultimate reality,” “timelessness,” insight that “all is One,” “unity with ultimate reality,” and similar experiences of enhanced consciousness.

The Future of the Science of the Mind

More scientific research needs to be done on meditation and higher states of consciousness. Human beings are singular in that we are able to transcend our animal instincts like perception and emotion to explore concepts of reason, morality and awareness of a unified cosmos or higher self. It is evident that Illumination Meditation can focus the mind and expand awareness for greater insight. Certainly the human race could benefit from more of that right now.

If you would like to read more about the roots of scientific mindfulness meditation, you are invited to explore the other articles in the Science Abbey Meditation Guide:

SCIENCE ABBEY MEDITATION GUIDE

I: Basic Meditation: Meditation Manual

II: Buddhist Insight Meditation

V: Scientific Mindfulness

NOTES