Zen Buddhist Meditation

While there are a number of schools of Zen, this article will focus on the Japanese Soto sect teaching of shikantaza, or “just sitting” method of meditation, probably the most straight-forward example of Zen Buddhist meditation.

Early Zen in Japan

Buddhism spread from China to Korea in the fourth century, and is said to have entered Japan sometime between the sixth and eighth centuries. When Chan was first established in Korea during the seventh century, it was pronounced “Soen,” and when it was finally introduced to Japan by Dainichibō Nōnin and Myōan Eisai in the twelfth century, it was called “Zen.” The Soto school, or Soto-shu, is the largest of the three traditional Zen sects in Japan, the other two being Rinzai and Ōbaku.

Myōan Eisai (1141-1215) spent time in China and was ordained in the Tendai sect, later returning to China for a period to become a teacher in the Linji tradition. He returned to Japan in 1191 and founded Hoon Temple in Kyushu, Japan’s first Zen temple. He brought with him Chinese tea seeds and introduced the tea tradition to Japan. Eisai subsequently founded Kennin-ji Temple in Kyoto in 1202, where he served as founding abbot and was buried in 1215.

Eihei Dogen, a student of Eisai’s, was ordained as a Tendai monk in Kyoto. Following in Eisai’s footsteps, he travelled to China in 1223 to study at Chan monasteries. Dogen received Dharma transmission from the thirteenth patriarch of Caodong, Tiantong Rujing (Japanese: Nyojo Zenji), the abbot of Qingde Temple on Tiangtong Mountain (Japanese: Tendosan Keitokuji).

Founding of Soto Zen

Eisai had written only a short description of Zen meditation in his Treatise on the Propagation of Zen for the Protection of the State (Kōzen gokokuron) in order to convince the government to lift its ban and promote Zen Buddhism. When Eihei Dogen returned to Kenninji in Japan, he wrote several essential Zen texts, beginning with the Fukanzazenji, the Universally Recommended Instructions for Meditation. This treatise introduced the practice of meditation called zazen to Japan.

The primary source for Dogen’s Fukanzazengi was the Zuochan yi, the earliest extant written instruction for Chan meditation, attributed to Changlu Zongze (died c. 1107). Zongze was the author of the Chanyuan Qinggui, or The Rules of Purity in the Chan Monastery, once thought to be the oldest existing Chan monastic code.

The Qinggui was the inspiration for many future codes, including Dogen’s code for Soto Zen monasteries, the Eihei Shingi, or Pure Standards for the Zen Community. Dogen founded the Eihei-ji monastery in the wilderness of Northern Japan in 1244 and remained its abbot until his death in 1253. Eihei-ji is the first of the two head Soto Zen temples in Japan.

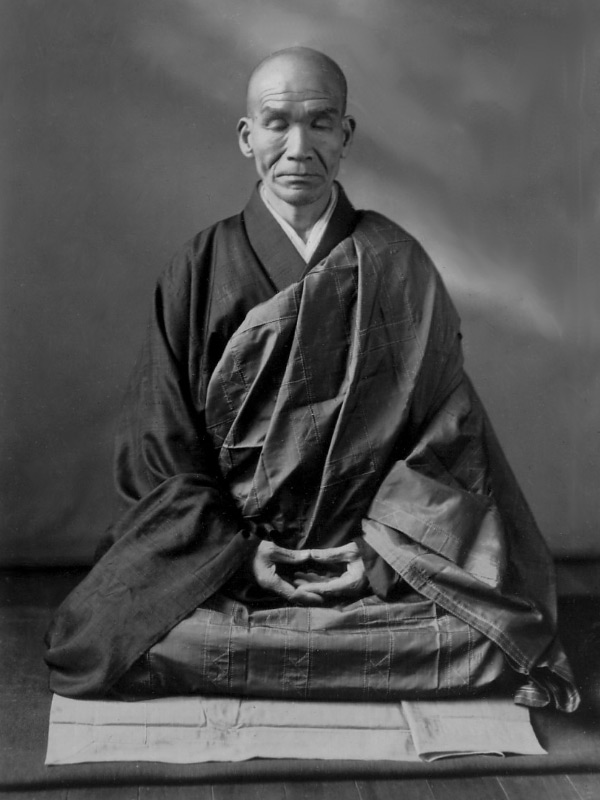

Keizan Jōkin (1268-1325), also known as Taiso Jōsai Daishi, is the second founder of the Soto Zen school in Japan. Keizan’s grandmother was a supporter of Dogen, his mother was an abbess at a Soto monastery, and he trained at Eihei-ji from age eight. Keizan founded a number of temples and popularized Soto Zen throughout Japan.

Keizan was the founder of Sōji-ji, the second of the two main Soto monasteries, with Dogen’s Eihei-ji. He is also known for his Transmission of the Light, a collection of sermons that form an account of the Soto lineage. This lineage is traced from Gautama Buddha to Dogen and his Dharma successor, Koun Ejō (1198-1280).

Instructions for Soto Zazen

The practice of Japanese Soto Zen requires deportment and dignified manners, especially for lay practitioners at sangha, and for monks at all times. Holding the open palms of the hands together so the fingertips are at the level of the nose is called gassho, a symbol of prayer also used in greetings, farewells, apologies, or in gratitude.

Soto Zen practitioners begin meditation by standing facing the wall and bowing at the waist in gassho, which is called monjin, then turn clockwise and do monjin facing away from the wall. This is a formal way of bowing to those who sit with you, as a symbol of respect, and it is also done ritualistically in solo practice.

Sit on a zafu, a small round pillow, which rests on a cushion called a zabuton, and turn clockwise to meditate facing the wall. It is also permissible to use a chair for health reasons or comfort. Make eight full breaths swaying left and right once during each complete breath, starting with large arcs and gradually decreasing the size of the movement. Hands may rest on the knees palms up.

The beginning of the meditation period is marked by hitting a bell three times, the first hit being moderate, the second being weaker, the third being strongest.[1] Gassho and begin. If you need to adjust or change position due to excessive pain, gassho before and after moving.

Dogen warns that meditation cannot truly be learned from a book, but that Buddhist instruction must be passed directly from Zen master to student, face to face. However, he did leave behind written instructions.

Dogen’s Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen (Fukan zazengi) instructs the meditator to find a place to sit, put down a thick mat and place a cushion over it. Sit in the half-lotus or full-lotus position with your left foot on top of your right thigh. Wear loose clothing, preferably robes, and arrange your attire neatly.

How to Sit

Rest your right hand on your left foot or leg and place your left hand in your right hand, touching the tips of the thumbs, in the Cosmic Mudra. Sit up straight, ears aligned with shoulders, nose aligned with navel, and avoid leaning in any direction. Keep your lips shut and teeth together, resting the tip of your tongue on the front of the roof of your mouth.

Keep your eyes open (about ⅓ of the way) looking past the tip of your nose and breathe softly through your nostrils. Breathe from the diaphragm (especially the hara). One may begin with three breaths through the mouth.

If one needs stimulation during meditation it is suggested that one put one’s mind in the palm of the left hand. The mind may also be concentrated between the eyes or on the crown of the head. One may also rock the body, widen the eyes, and take a couple of hard breaths through the mouth.

If your mind is disturbed, focus on the navel or tip of the nose. One may be mindful of the body, count the breaths, or concentrate on a koan. These techniques are only used to settle and focus the mind and are not essential to Soto zazen.

The bell is hit once to signal the end of the meditation. Bow facing the wall in recognition of ending the meditation period. Sway the upper body back and forth eight times with the breath, beginning with small movements and gradually increasing the motion.

Turn clockwise and stand facing away from the wall. Then turn clockwise to face the wall and adjust your zafu to its regular shape. Bow to the wall and then turn clockwise again to bow to those in the room, or in solo practice, bow to the cosmos.

It is suggested that one move slowly directly following meditation and maintain one’s state of concentration as much as possible throughout the day. One may stretch, rub the eyes or massage the body. Kinhin, or walking meditation, is recommended.

Although the above describes the physical dimensions of zazen, the most important element of meditation is what happens in the mind. Although Dogen inherited his tradition from Gautama Buddha through the lineage of Chan patriarchs, Soto meditation is distinguished by Dogen’s unique conception of zazen, known as shikantaza.

Ancient Origins of Shikantaza

In the Chan Buddhist tradition of Gautama Buddha, Bodhidharma and Huineng, Silent Illumination is not the restriction of thoughts, the extinguishing of emotion, or the stopping of the mind.

It is not visualization of emptiness or contemplation on the nature of the cosmos. It is not the denial of enlightenment as an end or of cultivation as a means of becoming a full Buddha. It is just sitting in calm awareness and allowing mental functions to pass naturally.

The deliberate effort of intention and concentration are replaced by the non-effort of a purposeless mind.

The Japanese abbot Rujing invented the term shikan-taza, “nothing but just sitting,” to refer to his practice of Caodong-style Silent Illumination. Shikantaza is a class of meditation without deliberate thoughts, visualizations, koans or counting the breath. It is a re-enactment of the Buddha sitting under the Bodhi tree.

To Dogen, there was no difference between practice of shikantaza and enlightenment; when done properly, there is only a “oneness of practice-enlightenment.” Shikantaza is not a means to an end; it is “the body and mind both dropping off” to reveal a Buddha.

Dogen’s shikantaza is the very epitome of Huineng’s sudden school method of enlightenment: the moment you do it, you are already Buddha. There is no need for cultivating ethics, wisdom or meditation when your essential nature is already all of these.

Dogen’s zazen is not trying to make a Buddha, it is the Buddha, equally realized in beginner and adept. Keizan’s Instructions on How to Do Pure Meditation (Zazenyojinki) calls this “Buddha Nature” one’s “Original Face” and “Original Nature.” This ineffable observer goes beyond the bodily senses, thoughts of good and evil, and even enlightenment and delusion.[2]

Zhiyi was the founder of the Tiantai tradition in China (Tendai in Japan), the first indigenous Chinese Buddhist system, under which Dogen studied. Zhiyi’s Lesser Treatise on Concentration and Insight (the Xiao Zhiguan) was the first Chinese Buddhist meditation manual. His Great Treatise on Concentration and Insight (the Mohe Zhiguan) became the central text of the Tientai school. Like the Theravada Vipassana schools, Zhiyi’s meditation consists of samatha (calm) and vipassana (insight).

The Zuochan yi of Zongze was rooted in the seventh century East Mountain Teaching of Chan patriarchs Dayi Daoxin and Daman Hongren, where records of the Chan lineage were first recorded. This school trained meditation centered on concentration on emptiness, an “ultimate principle” (such as a Buddha), or other object, with the goal of Samadhi.

Zhiyi offers methods that involve philosophical contemplation about the emptiness of thoughts and the suppression of thoughts through sheer concentration. While Zongze was influenced by Zhiyi, he instead prescribes a passive, lucid awareness of thoughts and other mental activity (which requires a natural flow of concentration). There must be non-judgment of good or evil as one allows oneself to simply forget all objects of the mind to become unified in mind. This is analogous to both shikantaza and the Daoist concept of wu-wei (non-action) in meditation.

Shikantaza & Non-thinking

In the Eihei Koroku Dogen discusses the breath, and says that his master taught that the breath comes from and returns to the “cinnabar field,” or “dantien.” He dismisses the method of counting breaths or placing attention on whether a breath is long or short.

On the action of the mind, Dogen agrees with Zongze, that with concentration “objects are forgotten” in order to “become unified.” The technique is to make the monk relaxed and joyful. This state of concentration and lucidity is to be maintained throughout the day.

One of Dogen’s most referenced stories involves the Tang dynasty Chan monk Yaoshan Weiyan (Japanese: Yakusan Igen), who taught to dispense with all phenomena to go beyond duality and reveal the original mind. The story appears in the “Zazen Shin” chapter of his Shobogenzo:

The master was sitting and a monk asked him, “What are you thinking of, sitting there, still as a mountain?”

The master answered, “I am thinking of not thinking” (That is, he was not deliberately thinking about anything, although he may have had thoughts.)

The monk then asked, “How can you think of not thinking?” (In other words, how can one not deliberately think about anything?)

The master answered, “Non-thinking.”

The master’s point is that what the master is thinking about is not the point. This is not really thinking about non-thinking at all – it is not thinking – it is just gently controlled awareness.

Thoughts and feelings naturally enter and pass out of the open field of observation. Volition and concentration are united and held just enough to maintain consciousness and attention. Shikantaza is thus a form of mindfulness, or intentional lucidity, which expands consciousness.

In his final revision of the Fukanzazengi, Dogen replaces the idea that objects should be forgotten with the explanation that shikantaza is about non-thinking, or “thinking of not thinking.”

Dogen’s shiryō is translated “thinking;” his fushiryō is usually “not thinking;” and hishiryō is “non-thinking.” The hi and the fu negating prefixes could be interchanged without clarifying or compounding the obscurity of the translation.[3]

Illumination Meditation

In shikantaza thoughts come and go without conscious direction. This state may be an otherwise unapproachable result, what Dogen refers to in the Shobogenzo Zanmaio Zanmai as the “sloughing off of body and mind” (shinjin datsuraku). Thus, enlightenment is a unified practice-realization.

Shikantaza is traditionally characterized as just sitting, without clinging to anything, and without purpose or goal. This “non-thinking” is the right attitude during meditation. That does not mean that it is without intent, concentration, or mindfulness.

The intent of shikantaza is to end suffering and be illumined by being a Buddha adhering to the Eightfold Path, especially Right Concentration and Right Mindfulness. Dogen’s idea of “acting as a Buddha” means doing shikantaza, but not necessarily while sitting down or even meditating; one can be in shikantaza anywhere and doing anything. According to Dogen, this state of mind has been transmitted face-to-face from Shakyamuni Buddha on through the Zen ancestors.

It may be argued that shikantaza is a state known as “no-mind” (Chinese Wuxin and Japanese Mushin). As the embodiment of perfect enlightenment shikantaza, more than anything else, expedites the experience of enlightenment. Normal waking consciousness is between unconsciousness and higher consciousness.

To fall asleep, we pretend to be asleep: to be awakened, we pretend to be awakened. Dogen’s Fukanzazengi reads more like zuochan poetry than a technical manual, and his specific form of zazen is unique to Dogen, but the text certainly follows in the Silent Illumination tradition.[4]

Buddhism traditionally relies on a formula of ethics (shila), wisdom (prajna) and meditation (dhyana). Chan and Zen place most emphasis on meditation. Ultimately, Zhiyi, Zongze and Dogen agree with the Indian Buddhists that the goal of meditation is Samadhi, an awareness beyond deluded thinking, as a condition for enlightenment.

At the core of Buddhism is Illumination meditation, a training examined and endorsed by science, especially under the name of mindfulness.

To read more about Buddhist meditation, Chinese Chan meditation and scientific mindfulness meditation, look at the other articles in the Science Abbey Meditation Guide series:

SCIENCE ABBEY MEDITATION GUIDE

I: Basic Meditation: Meditation Manual

II: Buddhist Insight Meditation

IV: Japanese Zen

NOTES