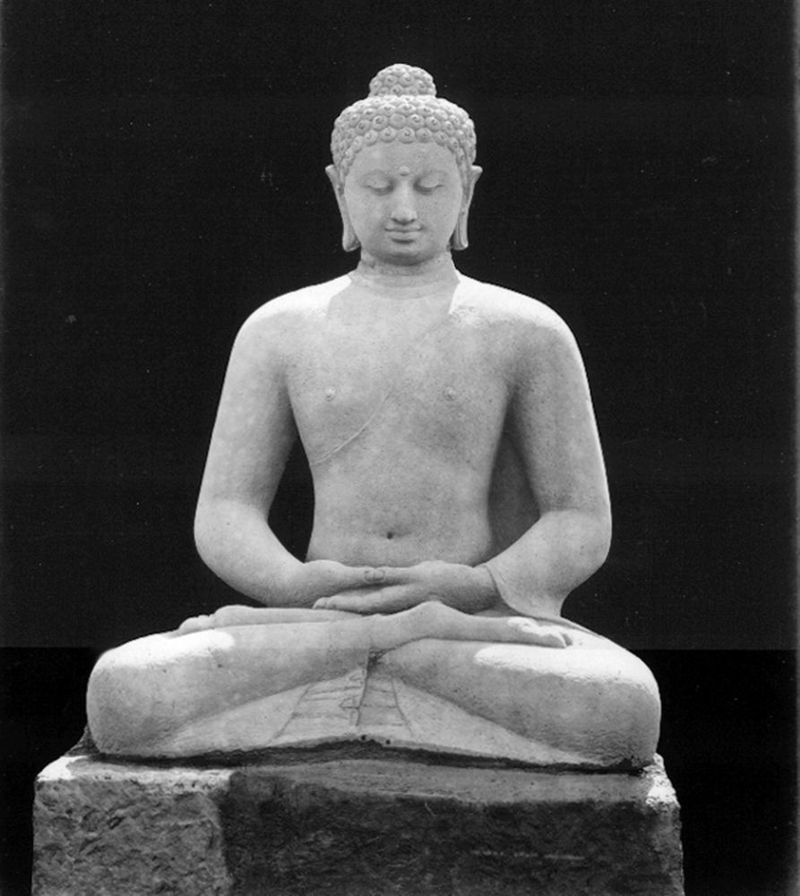

The Buddha: Siddhartha Gautama

The Buddha’s meditation is a way of life, a religion, rooted in the simple act of sitting calmly and being awake to reality. The Buddha was born Prince Siddhartha Gautama probably in the sixth century BCE into the Shakya clan, which is why he is sometimes referred to as Buddha Shakyamuni, “Buddha of the Shakya clan.” “Buddha” means literally, the “awakened one,” or “enlightened one.”

Gautama was born in Lumbini, in modern day Nepal, and raised in the Shakya capital, Kapilvastu. His father was chieftain or king. Legend built up around his life that told the story of his sheltered life behind the royal gates; wealthy, pampered, and protected from any knowledge of old age, disease or death.

After he was married and had produced offspring he took his famous first excursion outside the royal grounds upon a chariot, and witnessed examples of the defects of life. In shock, the prince left his home to become a wandering ascetic seeking liberation from ignorance, selfishness and suffering. After experiencing both the life of luxury and the ascetic’s severe self-denial, Gautama understood the Middle Way, the way of life that balanced natural pleasures with self-control.

The historical Buddha studied the ideas of the five Upanishads written at the time (Brihadaranyaka, Chandogya, Kaushitaki, Aitareya, and Taittiriya Upanishads) and streamlined Indian philosophy into a practical system of personal development. This is key: Gautama sat in meditation in order to be liberated, and he transcended attachment to desire, fear and even enlightenment.

By legend, Gautama sat beneath the Bodhi tree for seven days, refusing to cease his meditation until he figured out how to break the cycle of death and rebirth. Gautama won an inner battle with the demon Mara, “Illusion,” and realized nirvana, escape from the cycle of death and rebirth. Gautama was then called Buddha, for he was awakened to reality.

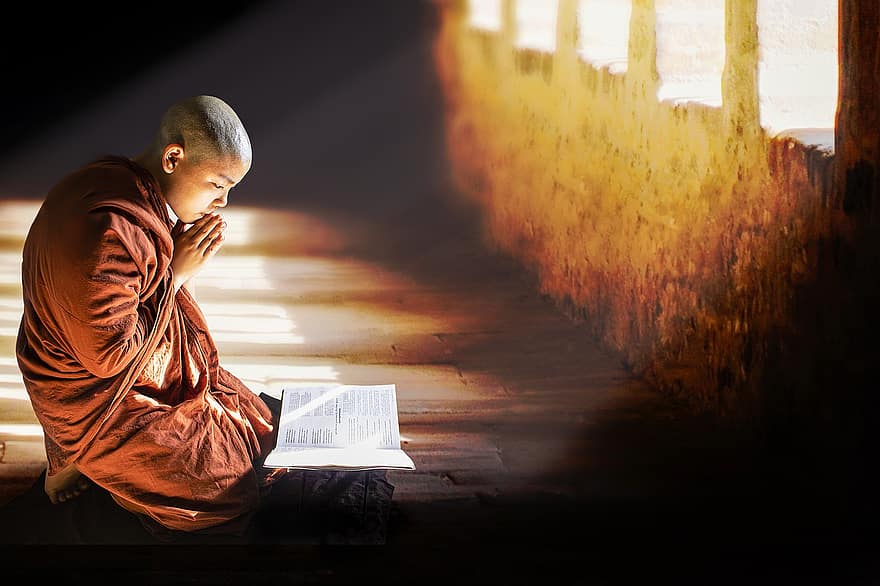

The Buddha then accepted disciples as mendicant monks (Pali: bhikkhu, Sanskrit: bhikṣu) and nuns (Pali: bhikkhunī, Sanskrit: bhikṣuṇī).

His central teaching was Illumination meditation.

The Buddha’s Ethics: The Four Noble Truths

Living requires more than just sitting in meditation, for survival, for health and for being a complete human being, or complete Buddha. Morality and ethics lay the foundation for a life of meditation and Buddhahood. A disordered life is not conducive to meditation or enlightenment.

The Buddhist layman makes vows called upāsaka (feminine upāsikā), monks make vows known as patimokkha (Pali) or pratimokṣa (Sanskrit), and all Mahayana Buddhists may take the Bodhisattva vows.

As Buddha, Gautama taught the Four Noble Truths:

- Life is suffering (discontent).

- Suffering is caused by craving.

- Craving may be overcome by

- The Eightfold Path:

- Right understanding

- Right purpose

- Right speech

- Right conduct

- Right livelihood

- Right effort

- Right alertness

- Right concentration

The goal of the Eightfold Path is nirvana. Nirvana literally means “blown out” or “extinguished” like a flame. The ignorant idea of the existence of a separate self is extinguished in meditation when it is seen through and understood as emptiness.

Nirvana is a mystical state of transcendence. This state is interpreted in different ways by the various Indian religions and philosophies. It is often viewed as the union of Atman (microcosm) and Brahman (macrocosm) and the realization of cosmic unity.

In Buddhism as in other Indian religions, nirvana means the same as moksha, the escape from samsara, the wheel of existence or cycle of birth, death and rebirth.

The Buddhist Scriptures

The Buddhists scriptures are contained within the Tipitaka (Sanskrit: Tripitaka), or “Three Baskets,” (vinaya, sutta and abhidhamma) compiled from about 500 BCE up through the first century BCE. The Sutta Pitaka, the Basket of Discourse, is a collection of about 10,000 suttas (Sanskrit: sutra, scripture) associated with the Buddha and his disciples.

The Vinaya Pitaka, the Basket of Discipline, is the first book of the Tipitaka. This is a mythic account of Buddha’s enlightenment, ordination of his first disciples, acceptance of the first donation of a monastic garden, and the development of the Buddhist monastic rule.

Of about twenty original early Indian Buddhist sects, there are only three extant monastic lineages: Mūlasarvāstivāda (Tibet), Dharmaguptaka (Central and East Asia: China, Korea, Japan, etc.), and Theravāda (Thailand).

The second book of the Vinaya Pitaka is the Khandhaka, which includes the Mahavagga and the Cullavagga texts. The section of the vinaya called the Mahavagga is the traditional account of the Buddha’s life after he attained enlightenment, his first sermons and the rules he made for his monks. It describes the first ordinations and his giving permission to ordain other monastics.

The Abhidhamma Piṭaka, or Basket of Further Doctrine, the final book of the Tipitaka, contains the teachings of Buddha’s disciples and later scholars on Buddhist epistemology, psychology, and ethics.

Ordination: Precepts and Vows

The Mahavagga presents the ordination ceremony and the Buddhist monastic vows. The life of the monk is determined in exact detail, as are the qualifications and restrictions for ordination.

Laymen and monastics of the Mahayana tradition take refuge in the “Three Jewels,” or “Triple Gem:” “I take my refuge in the Buddha, I take my refuge in the Dhamma (Sanskrit: Dharma, the teachings of Buddhism), I take my refuge in the Sangha (community).”

Lay vows called the Five Precepts are taken during an initiation ceremony:

- I will not kill a sentient being

- I will not steal

- I will refrain from sexual misconduct

- I will refrain from false speech

- I will refrain from intoxication

Mahayana Buddhists take the vows of the Four Bodhisattva Precepts:

- Beings are numberless; I vow to liberate them all.

- Delusions, desires, anxiety and hate are inexhaustible; I vow to end them.

- Dharma gates (Buddhist teachings) are boundless; I vow to enter (learn) them all.

- The Buddha Way is unsurpassable; I vow to realize it.

The sixth century Chinese Mahayana Brahma’s Net Sutra describes the Ten Major Precepts and the Forty-Eight Minor Precepts recognized by Chan Buddhism. This sutra also gives an account of Vairocana Buddha; the Primordial Buddha who is the embodiment of the Dharma.

There are sixteen Bodhisattva Precepts in Soto Zen, beginning with the “Three Treasures” (Three Jewels), followed by the “Three Pure Precepts” and the “Ten Grave Precepts.”[1]

The vinayas (monastic codes) of the various branches of Buddhism have developed different sets of rules. Traditional Theravada Buddhism has 227 rules for ordained bhikkhus (monks) and 311 for bhikkhunis (nuns).

Chan and Zen monastics follow the codes of their respective schools, known as “pure standards” or “rules of purity,” which delineate lives of daily ritual as well as weekly, monthly and annual ceremonies all centered around communal meditation.

The Buddha’s Meditation: Mindfulness

Early Buddhism originally focused on dhyana, mindfulness meditation leading to Samadhi, enlightenment. Within the first millennium of Buddhism, monks analyzed meditation further and categorized it into a combination of two parts: Samatha and Vipassanā.

Samatha, which means “calm,” is the calming of the mind by concentrating on the breath or an object of meditation. Vipassana means “insight” into the nature of reality being of three characteristics: unsatisfactory, impermanent, and devoid of selfness. Mindfulness was for purification, overcoming suffering, discovering truth and realizing nibbana (liberation.)

The Satipatṭhāna Sutta, or The Discourse on Establishing Mindfulness and its sister text, the Mahāsatipatṭhāna Sutta, or The Great Discourse on Establishing Mindfulness, are dialogues (suttas) created after Buddhism had spread to the “outskirts of the Kuru country,” modern Delhi, probably before 20 BCE.[2] With the Ānāpānasati Sutta they established the practice of mindfulness (sati) meditation and thus became key writings within the Pali Canon.

The discourses suggest meditations of bringing mindfulness to bear on the breath, the posture, the physical body, feelings of pleasure and pain, the mind and its contents, emotions, the objects of perception and various aspects of life.

The fifth century text Visuddhimagga, the Path of Purification, written by Buddhagosa, is next in importance in Theravada only to the Tipitaka.[3] This book lists forty meditation subjects, including, like the Satipatthāna Sutta, the four elements, the breath and foul things, but also suggests ideas like divine abodes, virtues of the gods and four immaterial states.

Buddhagosa describes samatha, vipassana and Samadhi. He states that the highest goal of Buddha’s meditation is Samadhi. Samadhi is a form of concentration. It is the cultivated state of awareness by which occurs the complete union of the mind known as enlightenment or illumination.

The Buddha’s Wisdom: The Dhammapada

Buddha received his ideas from the Upanishads and streamlined Indian philosophy into a practical system of personal development. According to tradition, three months after the death of Buddha, in about 400 BCE, about 500 arhats held the First Buddhist Council in Rajgir.

These monks began the tradition of recitation of the Sutta Pitaka as the means of orally preserving the Buddha’s teachings. Thirty years later the Vinaya Pitaka was first recited. The whole Tipitaka was transmitted orally during the reign of the Indian King Ashoka in the third century BCE.

The earliest known Buddhist writings are King Ashoka’s Buddhist lessons carved into cliffs, caves and sandstone pillars within his Edicts of Ashoka. The Tipitaka was finally written down during the Fourth Buddhist Council in Sri Lanka in 29 BCE, over 450 years after the death of the Buddha. This first Buddhist canon is known today as the Pali Canon of Theravada Buddhism.

The Gandharan texts of the Dharmaguptaka, dating from the first century BCE to about the third century CE, are the oldest surviving manuscripts of Buddhism and of South Asia. They include the Theravada Tipitaka and some Mahayana texts.

Within the Pali Canon is the central treatise of Buddhism, the Dhammapada, a third century BCE collection of the sayings of the Buddha.[4] The central practice of Buddhism is, of course, meditation. In Chapter 8 of the Dhammapada, “Thousands,” verses 100[5] and 111,[6] tranquility (samatha) and insight meditation (vipassana) is praised as superior to ignorance, confusion and immorality.

Chapter 14, “Buddha,” verse 181 reads, “The wise who are devoted to meditation (Pali: jhana, Sanskrit: dhyana) and delight in the peace of renunciation, these mindful ones, even the gods hold dear.” This important chapter also mentions, in verses 190 – 92, the supreme refuge being the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha, as well as the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path.

The Dhammapada Chapter 20, “The Path,” verse 282, reads: “Wisdom is born of meditation (‘yoga’). Without meditation, wisdom decays. Knowing this twofold path of gain and loss, conduct yourself so that wisdom grows.” The legend associated with this verse relates that the senior monk Potthila was conceited because of his knowledge of the Tipitaka.

Despite the man’s knowledge, Buddha always referred to him as “Useless Potthila.” This chastisement caused the monk to retreat to a remote monastery and accept the tutorship of an enlightened child novice. Following his new training regimen, Potthila meditated and realized enlightenment.[7]

Chapter 21, in verses 296 – 301, advises Gautama Buddha’s disciples to be mindful all day and night of the Buddha, the Dharma, the Sangha, and the body. His disciples are to delight in being always compassionate and in Bhavana, which means spiritual cultivation or contemplation, in the sense of meditation.

Chapter 25, “The Bhikkhu” (“The Buddhist Monk”), verse 372, asserts, “There is no meditation for one without insight/wisdom. There is no insight/wisdom for one without meditation. One who has both meditation and insight/wisdom is close to nirvana (liberation).

The Main Branches of Buddhism

While several traditions arose from various early schools, the two main branches that developed from the Buddha’s teachings are the Nikaya and Mahayana. In the early days, both could exist within the same monastery. Nikaya means “volume” or “collection,” indicating literature, but refers to Buddhist schools within monastic fraternities. By tradition there were eighteen to twenty early nikayas. Theravada Buddhism developed from these early teachings.

Theravada Buddhism, the Way of the Elders, is a line of unbroken tradition from the Buddha and his disciples. It is the oldest continuous school of Buddhism. The other two extant Vinaya lineages are the Dharmaguptaka and the Mūlasarvāstivāda.

“Mahayana” means “great vehicle,” for those who came up with the term in first or second century India considered the older tradition to be the Hinayana, or “lesser vehicle” of Buddhism. What was called “Hinayana” is therefore more appropriately called the Nikaya tradition.

The Mahayana branch includes Chinese Chan, Japanese Zen, Korean Seon and Vietnamese Thiền. Other surviving Mahayana schools are the Chinese Tiantai (and its equivalents, such as Japanese Tendai), Huayan (Japanese Kegon) and Pure Land Buddhism.

Mahayana Pure Land Buddhism is distinctive for its visualization and contemplation of Amitābha Buddha – the Buddha of Infinite Light and Life, a Buddha of boundless love – his bodhisattvas and his world, Sukhavati (“Ultimate Bliss”), the Pure Land.

The name of Amitabha is repeated in Vajrayana mantra, as well. In fact, Tibetan traditions have developed visualizations in the thousands. Along with samatha, vipassana and mindfulness of breathing, the Chinese Tiantai school contemplates the world of emptiness, the world of form, and the Middle Way between them. The esoteric teaching of the Japanese Tendai school, called Mikkyō, uses visualizations along with mantras and mudras.

Vajrayana Buddhism, encompassing the esoteric schools of Tibetan Buddhism, as well as the Japanese Tendai and Shingon, is sometimes classed as Mahayana but may otherwise be regarded as its own branch, altogether. Vajrayana is focused upon symbolism, ritual and magic (like extra-sensory perception). It is also known as Mantrayana for its use of mantra, or chant. Vajrayana is a form of symbolic alchemy and is also known as Tantric Buddhism.

The great Buddhist philosopher Nagarjuna (c. 150 – 250 CE) is said to have transformed base objects into gold at his monastery using the methods of Vajrayana, an allegory of the inner alchemist’s transformation of base existence into enlightenment.

Tantric techniques fall under the categories of yoga (psycho-physical exercises), mantra (chant), yantra (magical diagrams), mandala (cosmological art), mudra (physical gestures) and maithuna (sexual cultivation). The goal of these practices is the cultivation of prajna, transcendent wisdom, sometimes personified as the goddess Prajnaparamita.

In practice most Mahayana lineages, both in monasteries and in the entire sangha (Buddhist community including monastics and laity), include traditions from several Mahayana schools. The Chinese Chan founder of the Dharma Drum Mountain tradition, Sheng-Yen (1931-2009), is famous for promoting the idea of a unified Chinese Buddhism.

Theravada Meditations

In the Pali language, Buddhist meditation is called Bhavana, although Bhavana more properly implies the entire holistic process of the cultivation of the mind. In Mahayana Bhavana is the simultaneous production of samatha and vipassana. In Theravada, it includes purification of the mind, the getting rid of obstructions; as well as cultivation of positive qualities like tranquility, concentration, compassion, memory, intelligence and will; and reaching nibbana (nirvana).

In Theravada Buddhist meditation the mind concentrates on one of forty subjects including, among other things, fire, water, earth, air, space, consciousness, the Buddha, the Sangha (Buddhist community), the mortal body, the breath, death and empty void.

Like yoga, these Buddhist exercises calm and relax the body and mind, allowing the practitioner to seek into the causes and remedies of disturbance or disorder. These meditations are meant to develop higher awareness and mental power along the way to the ultimate goal of Samadhi, or one-pointedness.

The final branch of the Buddhist Eightfold Noble Path is Samma samadhi, “right concentration,” a reference to meditation. Just before that is Samma sati, “right mindfulness.” According to the Anguttara Nikaya of the Theravada school’s first century Pali Canon, Buddha taught nine stages of meditative absorption, or nine jhanas.

The Jhanas

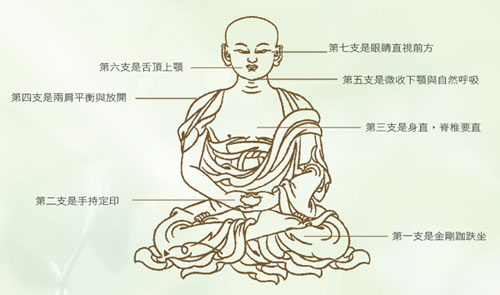

Sitting in a yogic posture, one first concentrates the attention upon the breath, and then proceeds to concentrate upon the nine Buddhist visualizations one by one as they arise. Beginners may take hours to sink into a deeper state, but with practice the process accelerates.

The first four jhanas are known as the material jhanas, after which thirty-two parts of the body are visualized along with colored disks. The last five jhanas are the immaterial jhanas.[8]

- Withdrawal causing pleasure and rapture, with directed thought and evaluation

- Composure causing pleasure and rapture; unified awareness free from directed thought & evaluation

- Equanimity and mindfulness causing a pleasant abiding

- Purity of equanimity and mindfulness; neither-pleasure-nor-pain

- Dimension of Infinite Space

- Dimension of Infinite Consciousness

- Dimension of Nothingness

- Dimension of neither perception nor non-perception

- Cessation of perception and feeling

The Seven Factors of Enlightenment are delineated in the Samyutta Nikaya of the Sutta Pitaka, one of the three books of the Pali Tipitaka, or Pali Canon, the central scripture of Theravada. They are also taught in the Abhidhamma and Pali commentaries.

These seven factors are states of mind considered to be leading to or indicative of enlightenment: Mindfulness, Investigation of the teachings (Dhamma or Dharma), Energy, Joy, Tranquility, Concentration and Equanimity.

In Vipassana, or modern insight meditation, the seven factors may be used strategically to help mitigate the five hindrances: sensual desire, anger or ill-will, sloth and torpor, restlessness and worry, and doubt.

If one is interested in learning this style of meditation, it is important to seek a qualified instructor from a Vipassana lineage, such as that of S. N. Goenka in the tradition of Sayagyi U Ba Khin. The Insight Meditation Center has some online instruction on its website.[9]

To read more on Chinese Chan, Japanese Zen, and Scientific Mindfulness, check out the other articles in the Science Abbey Meditation Guide series:

SCIENCE ABBEY MEDITATION GUIDE

I: Basic Meditation: Meditation Manual

II: Buddhist Insight Meditation

NOTES