Exploring the moral and legal obligations of a secular scientific humanist democracy when dealing with individuals or groups that threaten human rights protections. It addresses whether such threats deserve equal rights and outlines a principled framework for responsible governance.

Table of Contents

I. Introduction: The Paradox of Tolerance and the Scientific Humanist Dilemma

II. Foundational Principles of Human Rights in an Integrated Humanist Society

III. Defining Threats to Human Rights and the Democratic Order

IV. The Limits of Freedom: Speech, Assembly, and Armament

V. Totalitarian, Extremist, and Terrorist Groups: Legal and Ethical Frameworks

VI. Moral and Legal Justifications for Restriction

VII. Procedural Safeguards and Oversight Mechanisms

VIII. Comparative Analysis: Lessons from History and Modern Democracies

IX. Policy Recommendations for a Secular Scientific Humanist State

X. Conclusion: Preserving Liberty by Protecting It From Its Enemies

I. Introduction: The Paradox of Tolerance and the Scientific Humanist Dilemma

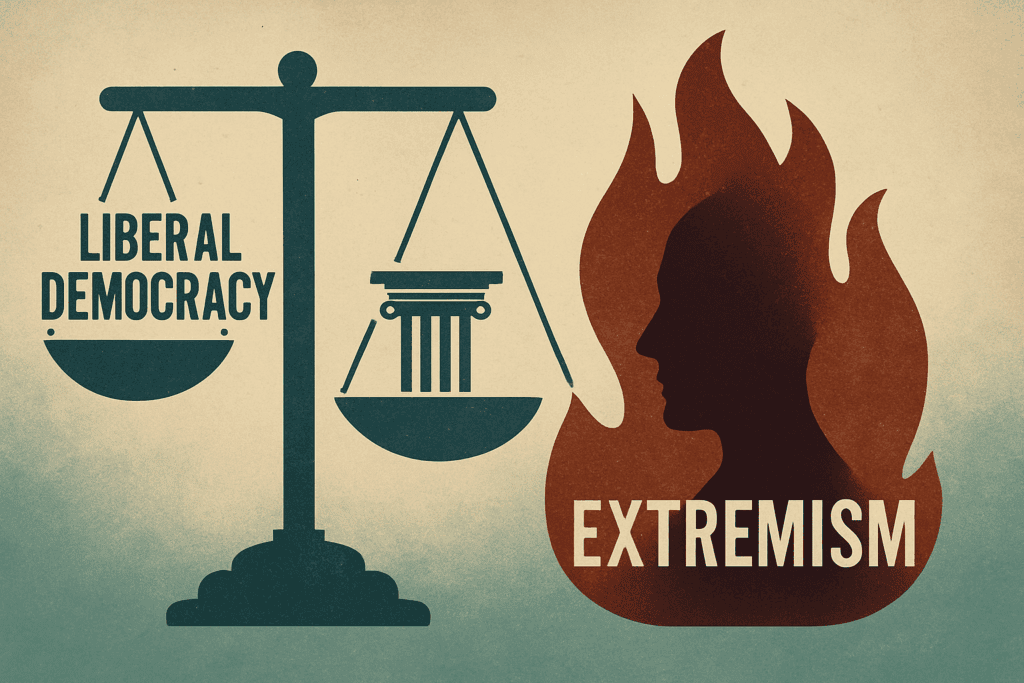

The defining challenge of a mature democracy is not simply to grant rights universally, but to uphold them meaningfully in the face of threats that seek to destroy them. A secular scientific humanist democracy—grounded in reason, evidence, and the moral dignity of all people—must continuously navigate a complex moral terrain: What should be done when individuals or groups use their rights to undermine the very society that grants them?

This question is not new, but it is urgent. The philosopher Karl Popper warned of the “paradox of tolerance”: a society that tolerates all things, even those that are fundamentally intolerant, will eventually destroy itself. In his words, “we should therefore claim, in the name of tolerance, the right not to tolerate the intolerant.” That principle is no mere abstraction. From the rise of fascism in the 20th century to the emergence of modern extremist movements—both religious and political—the threat of using liberty as a weapon against liberty has proven real, persistent, and deadly.

In an Integrated Humanist society, the rights to speak, assemble, and bear arms are not sacred dogmas granted by divine authority—they are ethical commitments, grounded in science, designed to preserve peace, flourishing, and justice. These rights do not exist in a vacuum; they operate within a moral and civic ecosystem. To misuse them in order to suppress others’ freedoms is to violate the very essence of a human rights society.

Yet this creates a dilemma. If we believe in the universality of human rights, can we ever justify limiting them—even for those who would do harm? Can we reconcile restriction with equality? Can we preserve liberty without sacrificing security, or vice versa?

This policy paper explores these questions through the lens of Integrated Humanism. It proposes that rights are not arbitrary entitlements but principled powers, derived from a balance between freedom and responsibility. It argues that while all persons are entitled to human rights by default, those who actively seek to destroy the human rights of others may, through due process, forfeit certain freedoms to protect the whole. It outlines the principles, procedures, and limits that a scientific humanist democracy must observe to act both justly and effectively in defense of its highest values.

This is not about vengeance, censorship, or authoritarian control. It is about moral coherence and civic survival. A democratic society, like an immune system, must know when and how to respond to existential threats. But unlike the immune system, it must do so ethically, transparently, and with the highest respect for human dignity—even when facing those who do not.

II. Foundational Principles of Human Rights in an Integrated Humanist Society

A secular scientific humanist democracy is not merely a system of governance—it is an ethical experiment in collective self-awareness. Its legitimacy stems not from tradition, theocracy, or ideology, but from a shared moral commitment to the dignity, equality, and flourishing of all sentient beings. At the heart of this commitment is the recognition and protection of human rights—not as fixed, dogmatic privileges, but as evolving, evidence-based principles designed to secure peace, cooperation, and personal fulfillment.

A. The Nature of Human Rights

Human rights in an Integrated Humanist framework are defined as the minimum set of freedoms, protections, and opportunities required for a human being to live a meaningful, dignified, and responsible life. They include but are not limited to:

- Freedom of thought, expression, and belief

- Freedom from violence, coercion, and discrimination

- Access to education, healthcare, and basic needs

- The right to participate in the civic, political, and cultural life of the community

- The right to bodily autonomy and legal due process

Unlike supernatural or absolutist justifications, Integrated Humanism grounds these rights in empirical observation:

- Humans thrive best in conditions of safety, liberty, and mutual respect.

- Societies that protect rights are more stable, prosperous, and intellectually vibrant.

- Violations of rights—systemic or individual—cause measurable harm, trauma, and regression.

Thus, rights are not simply moral ideals; they are functional necessities for a healthy civilization.

B. Rights as Relational and Reciprocal

A core principle of scientific humanism is that rights are not isolated. They operate in a network of mutual recognition and responsibility. One person’s freedom must not invalidate or destroy another’s. This relational understanding distinguishes Integrated Humanism from both libertarian absolutism and authoritarian collectivism.

Rights are:

- Universal by default: All humans are presumed equal in their right to live and grow.

- Contextual in practice: Rights may be limited only under strict, evidence-based conditions—never arbitrarily.

- Reciprocal in spirit: Those who consistently violate others’ rights may lose the moral and legal standing to fully exercise their own.

This reciprocity is not retributive—it is protective. It ensures that the community’s commitment to universal dignity is not nullified by those who deny it.

C. Human Rights as Evolving Scientific Commitments

Scientific humanism embraces the idea that moral principles can and should evolve with evidence. As our understanding of psychology, sociology, health, and conflict expands, so must our definitions of justice and harm. Integrated Humanist societies periodically revise their rights frameworks, not by political whim but by ethical review, citizen engagement, and scientific input.

For instance:

- Neuropsychology and trauma research have reshaped our understanding of cruelty and punishment.

- Advances in climate science have expanded the concept of environmental rights.

- Technology and AI ethics now affect rights to privacy, identity, and autonomy.

Thus, an Integrated Humanist state sees rights not as ossified statutes but as living policies—empirically informed and morally upheld.

D. The State’s Role as Guardian of Rights

The secular scientific humanist state has a moral obligation to serve as the protector and enabler of human rights—not simply as a passive arbiter, but as an active guardian. Its duties include:

- Preventing the erosion of rights by authoritarian ideologies or violent factions

- Upholding the rule of law as a mechanism for justice, not oppression

- Investing in education, transparency, and participatory governance

- Protecting vulnerable populations from systemic neglect or targeted abuse

To preserve the rights of the whole, it must sometimes limit the freedoms of those who act to destroy them. But it must do so with full accountability, transparency, and fidelity to its foundational principles.

III. Defining Threats to Human Rights and the Democratic Order

Before any restriction of rights can be justified, a secular scientific humanist democracy must clearly define what constitutes a credible threat—not in ideological terms, but through evidence-based, morally defensible criteria. A mature society must distinguish between those who merely disagree with humanist values and those who seek, through action or organized effort, to dismantle the very structure of rights and dignity upon which society rests.

A. The Difference Between Dissent and Destruction

Integrated Humanism welcomes intellectual disagreement. It does not demand ideological conformity. Criticism of government policies, secularism, or even scientific methods is not, in itself, dangerous—it is vital. Dissent, when peaceful and honest, is a key mechanism of moral and scientific progress.

However, a line is crossed when dissent becomes:

- Incitement to violence (e.g. calling for physical harm to minority groups or officials)

- Systemic disinformation (e.g. coordinated denial of pandemics or climate science with intent to sabotage public health or democratic process)

- Organized subversion (e.g. plots to overturn democracy or impose authoritarian rule through intimidation, terrorism, or rebellion)

Speech and organization that serve to undermine the existence of rights themselves is no longer protected dissent—it is existential sabotage.

B. Categories of Threats

To ensure clarity and fairness, threats may be broadly categorized as follows:

- Ideological Threats

- Worldviews or doctrines explicitly opposed to democracy, equality, or the rights of others.

- Examples: White nationalism, jihadist theocracy, violent theocratic fundamentalism, unrepentant neo-Nazism

- Worldviews or doctrines explicitly opposed to democracy, equality, or the rights of others.

- Organizational Threats

- Groups or movements with a history or declared goal of engaging in or supporting violence, terror, or authoritarian governance.

- Examples: Known terror organizations, paramilitary cults, hate groups, insurrectionist militias

- Groups or movements with a history or declared goal of engaging in or supporting violence, terror, or authoritarian governance.

- Behavioral Threats

- Individuals or networks repeatedly engaged in hate crimes, illegal stockpiling of arms for political purposes, harassment campaigns, targeted sabotage, or organized insurrection.

- These may act independently of any formal group but present empirical risk based on conduct

- Individuals or networks repeatedly engaged in hate crimes, illegal stockpiling of arms for political purposes, harassment campaigns, targeted sabotage, or organized insurrection.

- Digital and Informational Threats

- Coordinated online disinformation campaigns that systematically erode trust in democratic institutions or incite destabilization

- Deepfake weaponization, algorithmic radicalization, and cyberterrorism fall under this category

- Coordinated online disinformation campaigns that systematically erode trust in democratic institutions or incite destabilization

These threats are not criminalized based on belief—but on intention, impact, and historical or empirical precedent.

C. Criteria for Designation as a Threat

No society should suppress based on suspicion or ideology alone. The following criteria should be required for designating an individual or group as a threat:

- Clear intent: Statements, documents, or behavior indicating desire to restrict or destroy others’ rights

- Organizational capacity: Means to act—such as funding, weapons, digital infrastructure, or membership networks

- Historical behavior: Proven past actions of violence, incitement, or systemic rights violations

- Likelihood of harm: Evidence-based projections of future damage if unchecked

These standards must be set not by political officeholders, but by a combination of judicial oversight, human rights scholars, and scientific advisory bodies.

D. Democratic vs. Anti-Democratic Forces

The ultimate distinction is not between left and right, secular and religious, or even radical and moderate. The line that matters is between democratic and anti-democratic forces.

- Democratic actors accept the rules of open dialogue, rule of law, and universal rights

- Anti-democratic actors seek to nullify those principles and replace them with exclusion, domination, or tyranny

It is the latter—regardless of their banner—who pose a true threat to the human rights project.

IV. The Limits of Freedom: Speech, Assembly, and Armament

In an Integrated Humanist democracy, rights are foundational—but they are not infinite. The freedoms of speech, assembly, and armament are essential to civic life, yet each must be understood not in absolute terms, but as conditional privileges governed by reason, moral responsibility, and the rights of others. No freedom may be used to destroy freedom itself.

A. Freedom of Speech

The right to express ideas—even unpopular ones—is a cornerstone of human development and social progress. Scientific inquiry, civil rights, and moral evolution have all depended on the ability to challenge prevailing norms.

But Integrated Humanism draws a critical distinction between:

- Speech that questions, critiques, or seeks reform, and

- Speech that incites, dehumanizes, or destabilizes the human rights framework

Protected:

- Criticism of government, religion, science, or prevailing ideologies

- Advocacy for unpopular ideas, including nonviolent calls for systemic change

- Artistic, scientific, or philosophical expression—even when controversial

Not Protected:

- Hate speech aimed at inciting violence or dehumanizing targeted groups

- Terrorist propaganda and radicalization content

- Willful dissemination of provably false claims in the service of violence, sabotage, or insurrection (e.g., election lies, pandemic disinformation intended to cause mass harm)

- Calls to arms outside of lawful defense or recognized civic militias

This distinction aligns with scientific research on speech and harm, showing that certain types of speech do cause real-world violence, trauma, and democratic erosion. The state’s role is not to police opinion but to interrupt the causal chains of harm before they escalate.

B. Freedom of Assembly

Peaceful assembly is the physical enactment of civic freedom. It builds community, enables protest, and pressures governments to remain accountable.

However, assembly rights do not extend to:

- Armed rallies with intent to intimidate

- Gatherings organized to plan or carry out illegal or violent activities

- Marches openly led by recognized hate or terror groups

- Public demonstrations that violate lawful health or safety measures (e.g. pandemic disobedience campaigns with proven public health risks)

Assemblies that mirror the values of democracy are protected. Those that explicitly aim to end democracy may be restricted under legal review.

C. Right to Bear Arms

In many societies, the right to own and carry weapons is treated as a symbol of independence. But in an Integrated Humanist state, weapons are tools—dangerous ones—with public and private implications.

The right to bear arms is:

- Conditional: Dependent on licensing, mental health screening, background checks, and civic training

- Purpose-bound: Intended for legitimate self-defense, law enforcement, regulated militia use, and rural protection—not for intimidation, insurrection, or political threat

- Revocable: Those found to be part of violent or anti-democratic movements should be disarmed through due process

The moral logic is clear: Weapons in the hands of those who would destroy the society that grants them must be treated as a form of active danger—not protected liberty.

D. Limits as Ethical Safeguards, Not Tyranny

Opponents of restriction often raise alarms about “slippery slopes” or censorship. But within an Integrated Humanist system, all restrictions must meet the following conditions:

- Empirical justification: Measurable risk, documented harm, or demonstrated historical precedent

- Proportionality: The least restrictive means necessary to prevent harm

- Due process: Right to appeal, legal representation, and public transparency

- Periodic review: Ongoing assessment to determine if the restriction is still warranted

These mechanisms ensure that limits on freedom are not the tools of oppression, but instruments of protection—for the society, for the vulnerable, and for the very idea of rights themselves.

V. Totalitarian, Extremist, and Terrorist Groups: Legal and Ethical Frameworks

Not all threats to democracy are the same—but those that take organized form present the most severe and immediate danger to a human rights society. Totalitarian, extremist, and terrorist groups operate not as participants in the democratic process, but as enemies of it. A secular scientific humanist democracy must therefore have a clear, consistent, and morally defensible framework for identifying and responding to such entities.

A. Definitions and Distinctions

To apply restrictions justly, the state must define its terms precisely:

- Totalitarian groups seek to impose absolute ideological or political control, eliminating dissent and often centralizing authority in a charismatic figure or ruling elite.

- Examples: fascist parties, theocratic cults, unregulated revolutionary factions advocating one-party rule.

- Examples: fascist parties, theocratic cults, unregulated revolutionary factions advocating one-party rule.

- Extremist groups reject pluralism and promote exclusionary ideologies that deny basic human rights to others, often targeting ethnic, religious, gender, or ideological minorities.

- Examples: white supremacist militias, jihadist fundamentalists, anti-democratic ethnostates-in-waiting.

- Examples: white supremacist militias, jihadist fundamentalists, anti-democratic ethnostates-in-waiting.

- Terrorist groups use or threaten violence against civilians to achieve political, religious, or ideological ends, undermining both human rights and social cohesion.

- Examples: groups involved in bombings, assassinations, mass shootings, or psychological terror campaigns.

- Examples: groups involved in bombings, assassinations, mass shootings, or psychological terror campaigns.

While these categories often overlap, the response must be tailored to the group’s structure, rhetoric, and real-world behavior.

B. Criteria for Designation

Groups should be designated as totalitarian, extremist, or terrorist entities only through a rigorous evidentiary process that includes:

- A charter, doctrine, or public statement advocating violence, repression, or destruction of human rights.

- A history of coordinated action (online or offline) resulting in criminal behavior, hate crimes, or civic disruption.

- Affiliations with already recognized violent or banned organizations, either domestic or foreign.

- Intent to form parallel power structures (shadow governments, militias, or religious courts) that contradict the democratic constitution.

Designations must be reviewable, challengeable, and nonpartisan, determined by an independent, multi-branch commission of legal scholars, civil rights advocates, security experts, and scientists.

C. Legal Consequences of Designation

Once designated, such groups face:

- Prohibition from organizing or recruiting in public or digital spaces

- Loss of tax-exempt status or political party legitimacy

- Banning from access to public funding, facilities, or civic platforms

- Prohibition on firearm possession by members and affiliates

- Freezing of bank accounts and investigation of funding sources

- Prosecution of leaders for incitement, conspiracy, or terrorism if applicable

Members may not be criminalized for mere belief—but association with a violent or anti-democratic organization constitutes grounds for scrutiny, restriction, or legal consequence if and only if tied to actual harmful behavior.

D. Rehabilitation vs. Prohibition

Integrated Humanism favors not merely punishment, but de-escalation and reformation. Depending on the nature of the group:

- Disengagement and deradicalization programs should be made available

- Anonymous exit pathways may be offered to members who renounce violence and rejoin civic life

- Public education and counter-messaging campaigns should be launched to expose the harm of totalitarian ideologies and offer better alternatives

Where transformation is possible, the door must remain open. But where existential harm is ongoing, the state has both the moral right and the moral duty to dismantle.

E. International Coordination and Precedent

Integrated Humanist states do not act in isolation. They may draw upon:

- United Nations designations of terror entities

- European Union and NATO counter-extremism protocols

- Intergovernmental intelligence-sharing agreements

- Precedents from post-WWII de-Nazification and post-apartheid legal reforms

International law provides both practical mechanisms and moral insight. The goal is not to wage war against ideas—but to shield democracy from the machinery of its destruction.

VI. Moral and Legal Justifications for Restriction

To restrict the rights of any person or group—even one advocating tyranny—is a serious moral act. It must be justified not by fear, revenge, or ideology, but by clear principles rooted in human dignity, justice, and the democratic commitment to protect the whole. A secular scientific humanist democracy must therefore articulate why restrictions are not only permissible but at times required.

A. Rights Are Not Absolute in Any Ethical Framework

No credible moral system—liberal, religious, or scientific—grants unlimited rights to all people under all circumstances. Every right exists in tension with others. The right to speak does not include the right to falsely shout “fire” in a crowded theater. The right to assemble does not extend to mob violence. Even bodily autonomy does not protect acts of assault.

From this perspective, restriction is not the opposite of rights—it is their guardian.

B. The Utilitarian Argument: Preventing the Greater Harm

One of the strongest justifications for restriction lies in the utilitarian principle: the greatest good for the greatest number. If allowing one person to spread violent hate leads to dozens being injured or killed, the calculus is clear. Limiting that one voice—through nonviolent and fair means—saves lives and preserves the peace.

This principle:

- Prioritizes preventive ethics over reactive punishment

- Respects empirical evidence about the harms of unchecked extremism

- Justifies proportionate restrictions to protect vulnerable populations and civic infrastructure

C. The Rights-Based Argument: No Right to Destroy Rights

From a rights theory standpoint, no one has the right to destroy the rights of others. If person A uses their platform to promote genocide, enslave others, or advocate dictatorship, they are no longer exercising a right—they are attacking the moral structure that made their voice possible.

This is where rights must be understood as:

- Relational: Our freedom exists alongside others’, not above it

- Reciprocal: Those who respect rights are protected; those who do not may face ethical limits

- Conditional: Based on conduct, not identity, belief, or mere association

Thus, protecting society from those who weaponize liberty against liberty is not a betrayal of democratic values—it is their ultimate defense.

D. The Democratic Argument: Safeguarding the System Itself

A democracy has no obligation to enable its own destruction. When anti-democratic forces exploit democratic processes to seize power and dismantle rights—as seen in fascist takeovers or extremist religious states—the state has the right and duty to prevent it.

Examples include:

- Weimar Germany’s legal failure to stop Hitler’s rise despite clear warnings

- Modern democracies that restrict Nazi, jihadist, or ultra-nationalist symbols and parties

- Israel’s legal disqualification of parties that incite racial hatred or deny the state’s democratic character

Democracy is not a suicide pact. It has every right to protect its own existence, so long as the methods are just.

E. The Scientific Humanist Argument: Evidence, Not Emotion

Finally, a scientific humanist framework emphasizes:

- Data over dogma: Decisions to restrict must be based on real harm, not public panic

- Independent review: Rights restrictions must be periodically reviewed by impartial bodies

- Transparency and appeal: Every individual or group must have the right to contest their designation or restriction

This approach avoids the traps of authoritarian overreach and fear-based policy. It ensures that even when freedom is limited, justice remains expansive.

VII. Procedural Safeguards and Oversight Mechanisms

In a secular scientific humanist democracy, the authority to restrict rights must always be accompanied by greater responsibility, transparency, and oversight. Without this, even the most well-intentioned policies risk descending into authoritarianism. The strength of such a society is not merely in what it stands against, but in how it holds itself accountable when it must act against threats.

A. Due Process as a Moral Imperative

Any restriction of rights must be governed by legally enshrined due process. This includes:

- Notification: Individuals or organizations must be informed of the specific reasons for restriction.

- Right to challenge: Access to independent tribunals and courts to appeal decisions.

- Legal representation: Guarantee of counsel, especially in cases of designation as extremist or dangerous.

- Time-bounded reviews: No restriction should be indefinite without periodic re-evaluation.

Due process affirms that the state does not wield power arbitrarily, but as a custodian of justice. It also builds public trust and ensures the system does not target political opponents, religious minorities, or unpopular thinkers without merit.

B. Independent Oversight Bodies

Integrated Humanist governance requires multiple tiers of institutional accountability. We recommend the following:

- Human Rights Tribunal

- A nonpartisan judicial body composed of legal experts, ethicists, and civic representatives tasked with reviewing restrictions and hearing appeals.

- A nonpartisan judicial body composed of legal experts, ethicists, and civic representatives tasked with reviewing restrictions and hearing appeals.

- Civil Liberties Ombudsman

- An independent office empowered to investigate abuses, hold hearings, and publish public reports.

- An independent office empowered to investigate abuses, hold hearings, and publish public reports.

- Scientific and Ethical Advisory Board

- Provides evidence-based assessments of speech, group behavior, and risks to public well-being.

- Provides evidence-based assessments of speech, group behavior, and risks to public well-being.

- Legislative Review Committee

- Elected officials responsible for annual audits of all security-based rights restrictions, including public disclosure and revision of outdated policies.

- Elected officials responsible for annual audits of all security-based rights restrictions, including public disclosure and revision of outdated policies.

These overlapping systems ensure that no restriction remains unexamined and that new threats are assessed with a moral and scientific lens.

C. Transparency as a Safeguard Against Corruption

All restriction actions should be subject to:

- Public records and accountability logs, except in cases of legitimate national security secrecy, with retroactive transparency

- Mandatory reporting to parliament or equivalent legislative body

- Data availability for journalistic and academic scrutiny, redacted only where necessary to protect lives or operational security

An Integrated Humanist democracy thrives when its actions are visible and justifiable. Secrecy should be rare and temporary—not a habit of power.

D. Proportionality and Tailored Measures

A rights restriction must be the least intrusive method that still effectively addresses the harm. This may include:

- De-platforming rather than imprisonment, when the danger is primarily rhetorical or virtual

- Civic disqualification without surveillance, when a person’s ideology is extreme but not yet actionable

- Behavioral monitoring or bans, without invasive digital tracking, unless an immediate public threat exists

Proportionality ensures that the response matches the actual threat—avoiding overreach while preserving the safety of the community.

E. Periodic Review and Sunset Clauses

All restrictions should include sunset clauses, meaning:

- They expire unless formally renewed after review

- New evidence must be considered before renewal

- Individuals must be allowed to demonstrate reformation or disengagement

This prevents permanent exclusion and aligns with the humanist belief in growth, change, and the moral possibility of redemption.

VIII. Comparative Analysis: Lessons from History and Modern Democracies

Throughout history, democracies have faced the paradox of how to preserve liberty when it is weaponized against itself. From the fall of democratic republics to the rise of authoritarian regimes, the global record provides sobering lessons and practical models. A secular scientific humanist democracy must learn from these examples—not to copy them blindly, but to apply their insights through principled adaptation.

A. Weimar Germany and the Failure to Act

The Weimar Republic’s downfall in 1933 is one of the most iconic warnings in democratic history. The Nazi Party, which used democratic rights to gain legal power, quickly abolished those very rights once in control.

Key failures included:

- Tolerating openly fascist speech and propaganda under the name of free speech

- Allowing anti-democratic parties to run for office without restriction

- Delaying legal action against organized paramilitary violence

- Failing to build public trust in democratic institutions and rule of law

Lesson: Democracy must draw firm lines before its enemies reach positions of irreversible power.

B. Post-WWII Germany: Constitutional Antifascism

In contrast, the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany, and later unified Germany) adopted a firm stance:

- Article 21(2) of the Basic Law bans political parties that seek to undermine the democratic order

- Neo-Nazi speech, Holocaust denial, and fascist symbols are criminal offenses

- Far-right groups are regularly monitored and disbanded by the Office for the Protection of the Constitution

Lesson: A strong democratic state can outlaw the means of tyranny without becoming tyrannical.

C. The United States: First Amendment and the Limits of Protection

The U.S. has taken a more speech-absolutist approach, with the First Amendment offering sweeping protections—even for hate speech—unless it incites “imminent lawless action” (Brandenburg v. Ohio, 1969).

This has:

- Preserved extraordinary free expression

- Allowed extremist groups to organize and march (e.g. Charlottesville, 2017)

- Led to legal debates over platform moderation, misinformation, and hate speech online

Lesson: Free speech without safeguards can permit rhetorical arson. Democratic ideals must evolve to distinguish between dissent and destruction.

D. The United Kingdom: Proscription and Hate Speech Laws

The UK maintains a list of proscribed terrorist organizations and restricts speech that incites hatred on the basis of race, religion, or sexual orientation.

- The Public Order Act 1986 prohibits incitement to violence or hatred

- The Terrorism Act 2000 allows the Home Secretary to ban groups deemed a national threat

Lesson: Balanced restriction, when legally justified and transparently enforced, can coexist with vibrant democratic debate.

E. Israel: Defending Democracy Amid Constant Threats

Israel’s High Court has disqualified political parties that incite racism or seek to dismantle the Jewish and democratic character of the state.

- Security laws allow preemptive detention, yet remain controversial

- Judicial independence has historically checked government overreach, though recently threatened

Lesson: A democracy surrounded by hostile threats must balance vigilance with judicial restraint—and constantly guard its own rule of law.

F. International Precedents and Treaties

- The European Court of Human Rights has upheld restrictions on hate speech and political extremism where such speech undermines democratic values.

- The UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) allows limitations on rights to protect “national security, public order, public health, or morals,” provided such limits are lawful, necessary, and proportionate.

Lesson: International norms support responsible restrictions when clearly justified and non-discriminatory.

These case studies reveal both the dangers of permissiveness and the pitfalls of overreach. The path forward for an Integrated Humanist democracy lies not in repeating past models, but in synthesizing their strengths through moral clarity, scientific discernment, and civic courage.

IX. Policy Recommendations for a Secular Scientific Humanist State

Having defined the moral, legal, and historical context, a secular scientific humanist democracy must now translate principle into practice. The following recommendations outline a coherent policy framework designed to protect human rights while responsibly managing threats to democratic integrity and public safety.

Each policy reflects Integrated Humanism’s commitment to reason, compassion, and evidence-based governance.

1. The Principle of Universal Rights by Default

- All individuals are presumed to possess equal rights, including speech, assembly, and legal protections, regardless of identity, belief, or background.

- No right is removed preemptively or arbitrarily; restriction requires due process, not suspicion or prejudice.

🡪 This ensures that democratic equality remains the starting point for all citizens.

2. Restriction Only on the Basis of Empirical Threat

- Rights may be limited only when there is clear, verifiable evidence that an individual or group poses a direct threat to the rights of others or the democratic order.

- This evidence may include incitement to violence, documented hate crimes, active participation in or support of terror/extremist organizations, or attempts to dismantle civic institutions.

🡪 This prevents abuse of power and ensures limits are based on behavior, not belief.

3. A Tiered Framework for Restriction

Rights restrictions should be proportional to the level of threat, with escalating consequences based on documented harm or intent:

- Level 1: Warnings, education, and public counterspeech (for misinformation and hateful rhetoric not yet linked to violence)

- Level 2: Temporary or platform-specific bans, disarmament, and exclusion from leadership roles (for known ideological group members)

- Level 3: Permanent de-platforming, dissolution of extremist organizations, loss of assembly rights (for organized, ongoing threats)

- Level 4: Prosecution and incarceration (for violence, terrorism, or insurrection)

🡪 This model ensures restraint while allowing firm response to increasing danger.

4. Prohibition of Organizations That Violate Core Rights

- Any political, religious, or ideological group whose stated aims or actions include the abolition of universal human rights may be banned.

- This includes groups advocating racial supremacy, religious totalitarianism, theocratic or fascist rule, genocide, or systemic disenfranchisement.

🡪 Freedom of association does not extend to associations that aim to destroy freedom.

5. Prohibition on Armed Extremism

- No private group or individual with a record of anti-democratic ideology or action should possess or stockpile weapons.

- Legal firearm ownership should require rigorous vetting, including ideological screening and civic training.

🡪 Weapons are not an inherent right—they are a conditional tool requiring moral trustworthiness.

6. Transparent Legal Designation of Threat Entities

- The state must maintain a public, reviewable registry of designated extremist or terror organizations, with clear reasons for designation and procedures for appeal or delisting.

- Individuals have the right to challenge their association with such groups through independent legal review.

🡪 This promotes transparency, avoids politicization, and allows for rehabilitation.

7. Civil Rehabilitation and Exit Pathways

- The government must offer educational and psychological support for individuals exiting extremist ideologies or groups.

- Reintegration programs should focus on civic education, moral responsibility, trauma healing, and employment pathways.

🡪 Humanism believes in redemption, not only in punishment.

8. Scientific Review and Periodic Policy Updates

- All restriction policies must be reviewed every 3–5 years based on:

- Social science research on radicalization and de-radicalization

- Technological changes (e.g. AI deepfakes, cyberterror)

- Shifting geopolitical risks

- Public and academic feedback

- Social science research on radicalization and de-radicalization

🡪 Human rights policy must evolve with empirical knowledge and changing conditions.

9. Multi-Layered Oversight and Due Process

- Independent review boards, courts, ombuds offices, and civic assemblies must be empowered to monitor, correct, and halt any misuse of restriction policies.

- All restrictions should include sunset clauses and appeal rights.

🡪 Freedom is safest when many eyes watch the watchmen.

10. Education as a First Line of Defense

- Human rights literacy, critical thinking, and civic ethics should be taught at all educational levels to reduce vulnerability to extremist ideologies.

- Schools, media, and public institutions must actively teach how to recognize and resist authoritarian rhetoric and conspiracy manipulation.

🡪 Prevention is the most humane and cost-effective form of protection.

This policy framework seeks to balance the moral weight of liberty with the ethical urgency of protection. It does not deny freedom—it defends it from those who would twist it into a weapon.

X. Conclusion: Preserving Liberty by Protecting It From Its Enemies

A secular scientific humanist democracy is founded on the principle that liberty, equality, and dignity are not gifts from a higher power—they are hard-won agreements forged in reason, compassion, and the collective desire to thrive together. But these agreements are fragile. They can be unraveled by those who, under the cover of rights, seek to deny those rights to others.

This policy paper has shown that the defense of human rights does not end with their declaration—it begins there. The challenge of modern governance is not only how to protect rights universally, but how to respond justly when individuals or groups act to destroy the very framework of those rights. The question is not whether to set limits—but how to do so without becoming what we oppose.

Integrated Humanism offers a way forward: one that neither permits tyranny to grow unchecked, nor allows the state to become tyrannical in the name of security. It affirms that:

- Rights are sacred because they are shared—not because they are absolute.

- Freedom must be tied to responsibility, and safeguarded by reason.

- Those who seek to dismantle democracy from within must be met with transparency, proportionality, and due process—not silence, not cruelty, but firm ethical resolve.

To defend tolerance, we must sometimes refuse to tolerate the intolerant. But we must do so with a clarity of purpose and an unwavering fidelity to the ideals we claim to protect. No punishment must be arbitrary. No person must be dehumanized. The moment we lose sight of the humanity of our enemies, we lose the foundation of humanism itself.

This is the burden and beauty of democratic maturity. In protecting liberty from its enemies, we prove that we deserve it. In defending rights with moral intelligence, we become the very society we aspire to be: not ruled by fear, but guided by conscience and governed by light.