A step-by-step guide to nonprofit governance. Build strong boards, ensure compliance, and align strategy with mission for maximum impact.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

Why nonprofit governance is both an art and a science in the Age of Intelligence - Historical Context: History of Nonprofit Organizations

From ancient charitable trusts to modern global foundations - Relational Context: Influential Nonprofits Across Sectors

Lessons from the oldest, wealthiest, and most powerful mission-driven institutions - Formal and Informal Instruction

Training leaders through education, mentorship, and parliamentary procedure - Forming a Nonprofit Organization

Building a strong legal and governance foundation from mission to operations - Duties of Officers and Governance Bodies

Roles, responsibilities, and interrelationships for effective leadership - Strategic & Operational Management

Aligning long-term vision with day-to-day execution - Financial Management and Legal Compliance

Ensuring stewardship, transparency, and adherence to the law - Practical Operations and Technology

Administrative systems, AI integration, facilities, and sustainability - Continuous Learning & Governance Best Practices

Creating a culture of evaluation, adaptation, and improvement - Conclusion

Nonprofit governance as a living discipline of stewardship and mission

Appendix: Assessment Tools for Nonprofit Boards

Practical evaluation methods for governance excellence

Introduction

Nonprofit governance is the art and science of directing organizations whose primary aim is mission, not profit. It is a discipline that blends legal structure, ethical leadership, strategic foresight, and operational discipline—applied in institutions that range from small community charities to global foundations with budgets in the billions.

While corporate governance has been extensively codified in law, regulation, and professional standards, nonprofit governance has historically been more variable. Some nonprofits operate with the procedural rigor of public corporations; others function informally, relying on a small circle of founders and volunteers. This variability is both a strength and a vulnerability: it allows adaptability to diverse missions and cultures, but it can also leave organizations exposed to inefficiency, mission drift, or loss of public trust.

The stakes are high. Nonprofits are entrusted with resources—financial, human, and reputational—that often originate from donors, grants, or public funds. They are also custodians of public confidence in the sectors they serve: education, health, the arts, humanitarian relief, scientific research, advocacy, and more. Sound governance ensures that this trust is well placed, that resources are used ethically and effectively, and that the organization’s mission is carried forward with integrity.

This Science Abbey guide approaches nonprofit governance as both an intellectual field and a practical craft. We draw on the theoretical foundations of governance explored in our Corporate Governance in the Age of Intelligence framework, but we adapt them to the distinct realities of the nonprofit sector. We also go beyond theory, providing practical, “boots-on-the-ground” instruction for day-to-day board and executive operations.

For the graduate student or experienced professional, this guide serves as both a foundational text and an advanced reference. It addresses historical and relational context, organizational formation, leadership duties, strategic and operational management, financial oversight, compliance, and the integration of technology—including AI—into governance practice. At the end, an appendix of assessment tools will allow boards and executives to evaluate and improve their governance performance on an ongoing basis.

Our aim is to equip nonprofit leaders to govern with clarity, confidence, and conscience—to serve not only their mission, but the public good.

1. Historical Context: History of Nonprofit Organizations

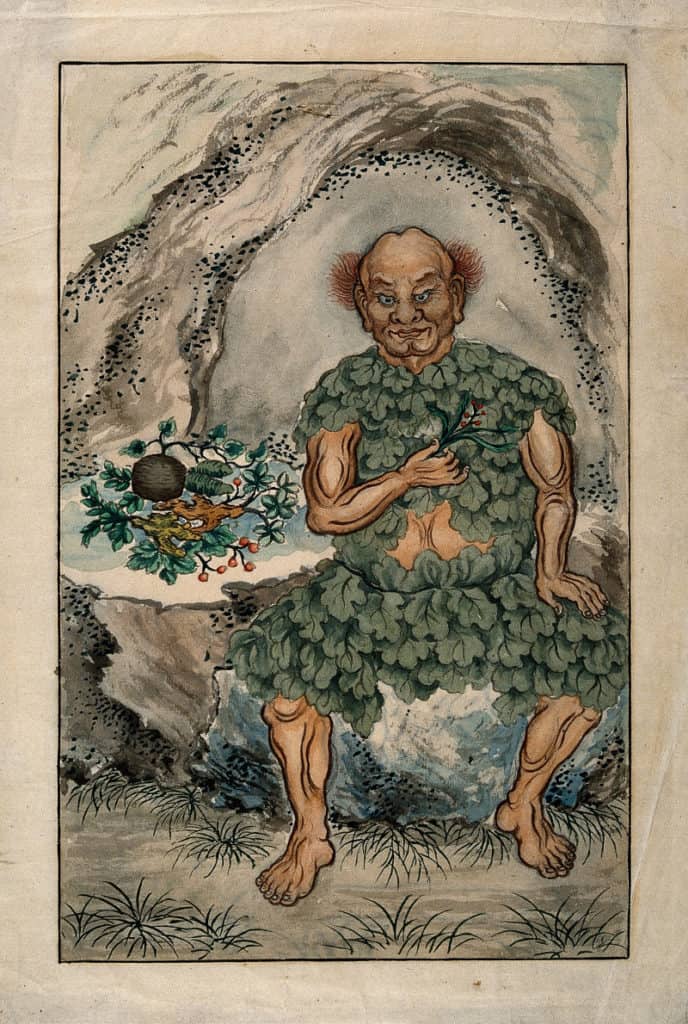

Nonprofit organizations have existed for as long as human societies have recognized the need for collective action beyond the scope of individual or family responsibility. In ancient civilizations, temples, guilds, and charitable trusts served functions remarkably similar to modern nonprofits—managing resources for the benefit of communities, education, public works, or the relief of the poor. Ancient Egypt’s temple granaries, Athens’ religious festivals funded by citizen “liturgies,” and the Confucian academies of China all represent early forms of mission-driven, noncommercial governance.

During the Middle Ages, religious orders, monastic communities, and charitable confraternities expanded the nonprofit role. In Europe, the Catholic Church administered hospitals, schools, and alms for the poor, often funded by bequests and endowments. In the Islamic world, the waqf (charitable trust) served similar purposes, protecting assets for perpetual public benefit. These institutions operated with governance systems—sometimes formal, sometimes customary—that ensured continuity of mission and stewardship of resources across generations.

The modern legal framework for nonprofits emerged in the 18th and 19th centuries, shaped by Enlightenment ideals, industrialization, and the growth of civil society. Voluntary associations and charitable trusts became vehicles for education reform, scientific advancement, abolitionist campaigns, and public health initiatives. In Britain, the Charitable Uses Act of 1601 and subsequent case law defined the purposes eligible for charitable status, a tradition carried into many common-law systems.

In the United States, the philanthropic model was transformed by figures like Andrew Carnegie, whose Gospel of Wealth (1889) argued that the wealthy had a moral obligation to distribute their fortunes for public good. Carnegie and contemporaries like John D. Rockefeller established large-scale foundations with professional governance structures—pioneering the combination of private wealth, public purpose, and formalized oversight.

The 20th century saw nonprofits expand into nearly every sphere of public life. Humanitarian organizations such as the Red Cross, cultural institutions like the Smithsonian, and advocacy groups from Amnesty International to Greenpeace began to operate with global reach. Legal systems adapted, offering tax exemptions to organizations serving recognized public purposes, and requiring varying degrees of reporting, transparency, and fiduciary duty.

In the early 21st century, nonprofit governance faces both unprecedented opportunity and complexity. Digital technology has enabled small organizations to operate globally, while the rise of “megafoundations” has concentrated enormous influence in a handful of private entities. Public scrutiny has intensified, with stakeholders demanding not only efficiency and accountability, but also diversity, equity, environmental responsibility, and measurable impact.

Understanding this historical arc is essential for today’s nonprofit leaders. It reveals that governance is not a static administrative task, but a living tradition—continuously adapting to political, cultural, and technological change. Nonprofit governance has always been about aligning mission with stewardship, and in the Age of Intelligence, that alignment must incorporate global connectivity, data-driven decision-making, and AI-assisted oversight without losing the human values at its core.

2. Relational Context: Influential Nonprofits Across Sectors

To understand the practice of nonprofit governance, it is instructive to examine those organizations that have set the tone—by virtue of their longevity, wealth, scope, or influence—for entire sectors. These institutions have not only advanced their missions but also shaped public expectations and governance standards for nonprofits worldwide.

Educational Institutions

The oldest universities, such as the University of Bologna (1088), Oxford (1096), and Harvard (1636), began as nonprofit corporations long before the term existed in modern law. Their governance models—boards of trustees, endowed funds, and statutes defining purpose—have become templates for educational institutions across the globe. Harvard’s multi-tiered governance, involving both a Corporation and a Board of Overseers, is a case study in balancing fiduciary oversight with academic freedom.

Global Humanitarian Organizations

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), founded in 1863, pioneered global humanitarian governance. Its neutrality, independence, and commitment to international law have been maintained through a governance structure that emphasizes both operational autonomy and strict adherence to its mission. The Red Cross model demonstrates how governance can safeguard credibility in politically charged environments.

Philanthropic Foundations

The Rockefeller Foundation (1913) and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (2000) illustrate the influence of private philanthropy on public health, education, and development. With assets in the tens of billions, these foundations operate with corporate-like governance systems: professional boards, strategic planning processes, rigorous grant evaluation, and transparent reporting. Yet they also face criticism for wielding disproportionate influence without electoral accountability—highlighting the importance of checks and balances even in privately funded nonprofits.

Advocacy and Civil Rights Organizations

The NAACP (1909) and Amnesty International (1961) have used governance to sustain long-term advocacy campaigns under shifting political conditions. Their boards balance fundraising imperatives with policy integrity, ensuring that strategic positions remain consistent with founding principles while adapting to contemporary challenges.

Cultural and Scientific Institutions

Institutions like the Smithsonian (1846) and the British Museum (1753) illustrate governance in organizations holding vast collections in trust for the public. Trustees in such contexts face unique challenges: balancing scholarly priorities, public engagement, ethical stewardship of artifacts, and the politics of cultural restitution.

Faith-Based Networks

The Catholic Church, global Protestant denominations, and Islamic charitable networks such as waqf-based institutions have complex, multi-layered governance systems blending theological authority with financial oversight. In the modern era, accreditation bodies like the Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability (ECFA) provide governance benchmarks for religious nonprofits, reinforcing trust among donors and members.

Critiques and Power Dynamics

The concept of the Nonprofit Industrial Complex captures a critical perspective: that powerful nonprofits can become intertwined with political and economic systems in ways that perpetuate the status quo rather than challenging it. This critique reminds governance leaders that independence, transparency, and mission fidelity are not automatically preserved by size or prestige—they require intentional protection.

Key Insight:

Studying influential nonprofits across sectors reveals that effective governance is not a single template but a series of tailored architectures—each shaped by mission, resources, and public expectations. Yet a common thread runs through the most successful: clear fiduciary duties, operational transparency, strong stakeholder engagement, and a governance culture that can survive leadership transitions.

3. Formal and Informal Instruction

Nonprofit governance is learned through a combination of formal education, professional development, and the gradual accumulation of practical wisdom. The most effective leaders cultivate both—the formal knowledge that provides structure and legitimacy, and the informal skills that make governance work in real, often unpredictable, settings.

Formal Instruction

Formal governance education provides nonprofit leaders with the frameworks, terminology, and legal grounding to fulfill their duties effectively. Graduate-level courses in nonprofit management, executive leadership programs, and sector-specific certifications offer structured learning in governance law, fiduciary duties, financial oversight, strategic planning, and ethics.

- University Programs: Many business and public policy schools offer concentrations or certificates in nonprofit management. Programs at institutions like Harvard Kennedy School, Stanford Graduate School of Business, and the University of Oxford’s Saïd Business School integrate nonprofit governance into broader leadership studies.

- Professional Certifications: Organizations like BoardSource and the National Council of Nonprofits offer governance training and resources. For a more general governance credential, nonprofit leaders may pursue corporate governance certifications such as the Corporate Governance Institute’s Professional Certificate or Society for Corporate Governance’s CCGP, adapting lessons from for-profit contexts to nonprofit realities.

- Continuing Legal Education (CLE): Attorneys serving nonprofit boards often maintain CLE credits in nonprofit law and governance, ensuring they stay current with regulatory changes.

Informal Instruction

Informal learning happens through mentorship, peer networks, and direct experience. Many nonprofit leaders refine their governance skills through:

- Board Service Across Organizations: Serving on multiple boards exposes leaders to different governance cultures and problem-solving approaches.

- Peer Exchanges and Roundtables: Regular discussions with peers provide practical insights into challenges like managing board politics, engaging donors, or responding to crises.

- On-the-Job Learning: For founders and executives, much of nonprofit governance is learned by doing—chairing meetings, navigating bylaws in real disputes, and responding to stakeholder needs in real time.

Parliamentary Procedure

The backbone of orderly nonprofit governance is a shared method of decision-making. Robert’s Rules of Order remains the most widely used parliamentary authority in the English-speaking nonprofit world. Even organizations that use a simplified form of parliamentary procedure benefit from its principles: clear agendas, recognized speakers, structured motions, and formal voting processes.

- Why It Matters: Parliamentary procedure protects minority voices, ensures transparency in decision-making, and provides a neutral structure for debate.

- Adaptation: Some nonprofits adopt customized rules of order to streamline small-board meetings while retaining procedural fairness.

Linking to Corporate Governance Education

While nonprofit and corporate governance differ in purpose and revenue models, they share common principles: fiduciary duties, strategic oversight, risk management, and accountability. The Science Abbey Corporate Governance in the Age of Intelligence framework provides a theoretical foundation that nonprofit leaders can adapt—particularly in areas like board composition, AI oversight, ESG integration, and stakeholder engagement.

Key Insight:

Formal instruction gives nonprofit leaders the architecture; informal instruction gives them the adaptability. A governance culture that values both is better prepared to meet mission goals while navigating legal, financial, and human complexities.

4. Forming a Nonprofit Organization

Establishing a nonprofit is as much an act of legal architecture as it is a declaration of mission. A strong foundation—built on precise documentation, compliance with jurisdictional laws, and a governance framework—ensures the organization can operate effectively, attract funding, and earn the trust of stakeholders from the very beginning.

Step 1: Defining Mission and Structure

Before filing a single document, founders must articulate the mission in clear, actionable terms. This mission statement should serve as a touchstone for all decisions, from governance structure to program design. Early decisions include:

- Membership Model vs. Self-Perpetuating Board: Will members elect the board (membership model) or will the board select its own successors (self-perpetuating)? Each has implications for accountability and agility.

- Scope of Operations: Local, national, or international? This affects jurisdictional compliance and strategic planning.

Step 2: Articles of Incorporation

The Articles of Incorporation establish the nonprofit as a legal entity with the state or national authority. These must typically include:

- Legal name and address

- Statement of nonprofit purpose aligned with charitable categories recognized by law

- Provisions for dissolution (how remaining assets will be distributed if the organization closes)

- Initial registered agent and incorporators

Tip: If applying for U.S. 501(c)(3) status, include specific IRS-required language in the purpose and dissolution clauses to avoid delays.

Step 3: Constitution and Bylaws

- Constitution: Outlines the organization’s foundational principles and objectives. It is often shorter and more enduring than the bylaws, serving as a philosophical compass.

- Bylaws: Provide the operational rules—how the board is structured, how officers are elected, how meetings are conducted, quorum requirements, and the authority of committees.

Bylaws should strike a balance between flexibility and clarity, allowing adaptation without sacrificing transparency.

Step 4: Registering and Applying for Tax-Exempt Status

In the U.S., most nonprofits seek federal tax exemption under IRS Section 501(c). Similar provisions exist in other jurisdictions. The process requires:

- Filing Form 1023 or 1023-EZ (for 501(c)(3) charities) or other appropriate forms for different classifications

- Providing a narrative of planned activities, budget projections, and governance structures

- Paying required filing fees and responding to any agency inquiries

Step 5: Governance Kickoff

- Appoint the Initial Board: Choose individuals who bring a mix of skills—finance, legal, fundraising, subject-matter expertise—and a demonstrated commitment to the mission.

- Adopt Bylaws and Policies: Ratify bylaws in the first board meeting and approve key governance policies (conflict of interest, whistleblower protection, financial controls).

- Set the Calendar: Establish the schedule for board and committee meetings, key reporting deadlines, and major organizational milestones.

Step 6: Operational Infrastructure

- Banking: Open organizational accounts, requiring dual signatures or equivalent controls for disbursements.

- Insurance: Secure directors’ and officers’ liability insurance, general liability coverage, and any sector-specific policies (e.g., event or volunteer insurance).

- Technology: Implement record-keeping systems for minutes, finances, and member data; consider secure cloud-based platforms for accessibility and compliance.

Key Insight:

A nonprofit’s earliest governance decisions often have the longest-lasting consequences. Clear mission language, robust bylaws, and well-chosen initial board members are not just formalities—they are the DNA of the organization’s governance culture.

5. Duties of Officers and Governance Bodies

A nonprofit’s governance framework comes alive through the people who occupy its leadership roles. Each officer and governance body carries distinct legal duties, practical responsibilities, and moral obligations. The effectiveness of the board and its committees depends on a clear understanding of these roles and the disciplined execution of their responsibilities.

Legal Duties: The Fiduciary Triad

All officers and board members are bound by three core fiduciary duties:

- Duty of Care – Act with the same prudence an ordinarily careful person would in a similar position, informed by adequate inquiry and preparation.

- Duty of Loyalty – Place the interests of the organization above personal or professional gain; avoid conflicts of interest.

- Duty of Obedience – Remain faithful to the organization’s mission and comply with applicable laws, governing documents, and policies.

Board Officers

Chair (President)

- Presides over board meetings, ensuring adherence to bylaws and parliamentary procedure.

- Sets agendas in collaboration with the executive director or CEO.

- Serves as the primary liaison between the board and executive leadership.

- Represents the organization in public and donor-facing events.

- Ensures committees are functioning effectively and reporting back to the board.

Vice Chair (Vice President)

- Supports the chair and assumes their duties in their absence.

- Often tasked with special projects or oversight of a particular committee.

- Prepares to step into the chair role in future leadership succession.

Secretary

- Maintains accurate minutes of meetings, preserving them as part of the organization’s official records.

- Manages notices of meetings and board communications.

- Oversees the safekeeping of corporate documents: bylaws, articles, policies, and historical records.

Treasurer

- Oversees the organization’s financial affairs, ensuring accurate reporting and compliance with accounting standards.

- Presents regular financial statements to the board and explains variances.

- Chairs the finance committee, if applicable, and liaises with auditors.

- Works with staff to develop budgets, monitor cash flow, and safeguard assets.

Other Officers

- Depending on size and mission, organizations may have roles such as Assistant Treasurer, Parliamentarian (to advise on procedural matters), or Chief Technology Officer (for tech-dependent missions).

Committees

Executive Committee

- Typically composed of board officers and sometimes key committee chairs.

- Acts on behalf of the full board between regular meetings, within limits set by the bylaws.

- Handles urgent matters and prepares the agenda for board meetings.

Standing Committees

- Finance/Audit Committee: Oversees budgets, audits, and fiscal policies.

- Governance/Nominating Committee: Manages board recruitment, orientation, and evaluation.

- Development/Fundraising Committee: Plans and coordinates donor relations and campaigns.

- Program Committee: Oversees program development, monitoring, and evaluation.

Ad Hoc Committees

- Created for specific projects or temporary needs, such as strategic planning or event coordination.

- Disbanded upon completion of their mandate.

Board as a Whole

- Approves strategic plans, budgets, and major policies.

- Monitors performance against mission and goals.

- Ensures legal and ethical compliance.

- Serves as ambassadors for the organization within their networks.

Key Insight:

Clarity of role prevents both overlap and neglect. When officers, committees, and the board as a whole understand their distinct yet interlocking functions, governance becomes efficient, transparent, and mission-focused.

6. Strategic & Operational Management

While governance defines the structure of nonprofit leadership, strategic and operational management ensure that structure translates into mission-driven action. Effective boards move fluidly between the “big picture” of long-term planning and the daily realities that keep an organization running smoothly.

Strategic Management

Strategic management is the discipline of aligning resources, programs, and policies with the nonprofit’s mission over time.

- Strategic Planning: Boards should lead or guide multi-year strategic planning processes, setting measurable goals and identifying key priorities.

- Environmental Scanning: Regularly assess political, economic, technological, and social factors that may affect the mission.

- Performance Measurement: Use program evaluations and impact assessments to guide resource allocation.

- Adaptive Strategy: Remain open to revising goals in response to new challenges or opportunities—without drifting from the core mission.

Meeting Preparation and Execution

Meetings are the board’s primary venue for governance action, and their effectiveness shapes the organization’s direction.

- Preparation: Distribute agendas and background materials at least a week in advance.

- Agenda Discipline: Structure meetings to prioritize strategic discussion over operational minutiae.

- Documentation: Accurate minutes capture decisions, assign responsibilities, and provide an official record for legal compliance.

- Follow-Up: Assign clear deadlines and accountability for action items.

Communication

Clear, consistent communication—between the board, executive leadership, staff, donors, and beneficiaries—prevents misunderstandings and builds trust.

- Internal: Use secure platforms for board communication; maintain open lines between officers and the executive director.

- External: Ensure public communications align with the mission and strategic plan. Board members should be able to articulate key messages when representing the organization.

Board Politics

Every board has its politics—informal alliances, differences of opinion, and sometimes tensions over authority.

- Managing Disagreements: Encourage respectful debate and avoid personalizing conflict.

- Chair’s Role: Facilitate inclusivity in discussions and prevent dominance by a few voices.

- Governance Culture: Establish norms of professionalism, confidentiality, and commitment to the mission over personal agendas.

Beneficiary Engagement

Beneficiaries are not just recipients of service—they are stakeholders whose perspectives can improve programs and governance.

- Direct Feedback: Include mechanisms for beneficiary input, such as surveys, advisory councils, or focus groups.

- Representation: Consider appointing beneficiary representatives to the board where appropriate.

Membership

In membership-based nonprofits, the member body often has formal powers, such as electing board members or approving bylaw changes.

- Engagement: Keep members informed of governance developments and invite participation in events and campaigns.

- Recruitment: Align membership recruitment with mission outreach, ensuring diversity and inclusivity.

Campaigns: Membership, Donations, and Advocacy

Campaigns require coordinated governance and operational execution.

- Fundraising Campaigns: Board members should lead by example in giving and in soliciting donations.

- Membership Drives: Pair with public education efforts to broaden the base of support.

- Advocacy Initiatives: Ensure compliance with lobbying laws and maintain alignment with mission and values.

Key Insight:

Strategic management is not separate from day-to-day operations; it is embedded in them. A nonprofit whose governance actively shapes meetings, communication, and stakeholder engagement will navigate both long-term goals and immediate challenges with greater coherence and impact.

7. Financial Management and Legal Compliance

Financial stewardship is at the heart of nonprofit governance. Every dollar entrusted to a nonprofit carries both opportunity and obligation: the opportunity to advance the mission, and the obligation to ensure that funds are managed with transparency, accountability, and legal integrity. The board’s role is not to handle every transaction, but to oversee systems, policies, and controls that safeguard the organization’s resources.

Income Streams

Nonprofits typically draw revenue from a mix of sources:

- Donations: Individual contributions, major gifts, bequests.

- Grants: Government contracts, foundation grants, competitive funding.

- Earned Income: Fees for service, ticket sales, educational programs, publications.

- Membership Dues: Recurring payments tied to benefits and engagement.

- Investment Income: Endowment earnings, interest, dividends.

Governance Implication: Boards must ensure diversification to reduce reliance on a single source, and adopt gift acceptance policies to avoid ethical or reputational risks.

Expenses and Unforeseen Costs

- Operating Costs: Salaries, facilities, program delivery, administration.

- Capital Expenditures: Technology upgrades, building repairs, major equipment.

- Contingencies: Legal disputes, emergency program funding, disaster response.

Best Practice: Maintain an operating reserve fund equal to at least three to six months of expenses.

For-Profit Ventures and Taxes

Some nonprofits operate revenue-generating businesses to support their mission.

- Unrelated Business Income Tax (UBIT): In the U.S., income from activities not substantially related to the mission may be taxable.

- Governance Oversight: Boards must monitor business ventures for mission alignment, financial sustainability, and compliance with applicable tax laws.

Legal Compliance

Compliance is not optional—it is the framework that allows the nonprofit to operate with legitimacy.

- Regulatory Filings: Annual reports to state regulators, IRS Form 990 (or international equivalents), corporate renewals.

- Employment Law: Adhering to wage, benefits, and safety standards for staff and volunteers.

- Fundraising Regulation: Compliance with charitable solicitation laws across jurisdictions.

- Privacy & Data Protection: Safeguarding donor and beneficiary information, especially in the age of GDPR and similar laws.

Insurance

- Directors & Officers (D&O) Liability Insurance: Protects board members against personal liability for decisions made in their official capacity.

- General Liability: Covers bodily injury or property damage claims.

- Specialized Coverage: Event insurance, professional liability, cyber liability.

Banking and Financial Controls

- Require dual authorization for disbursements above a set threshold.

- Reconcile accounts monthly and review financial statements at every board meeting.

- Conduct annual independent audits or financial reviews, depending on legal requirements and organizational size.

Key Insight:

The credibility of a nonprofit’s governance is inseparable from its financial integrity. Transparent reporting, prudent reserves, diversified income, and rigorous compliance systems are not just best practices—they are the conditions under which public trust and mission effectiveness flourish.

8. Practical Operations and Technology

The governance of a nonprofit does not end at the board table. Day-to-day operations—the administrative backbone, technological infrastructure, and physical environment—are where strategic decisions are implemented and tested. A board’s role is to ensure that these operations are well-resourced, efficiently managed, and aligned with mission priorities.

Administrative Foundations

- Record Keeping: Maintain secure, organized records of minutes, financial reports, contracts, and key correspondence. Cloud-based systems with appropriate permissions allow secure access for authorized board members and staff.

- Scheduling: Use centralized calendars for board, committee, and program activities to avoid conflicts and ensure full participation.

- Policy Manual: Maintain a living document that consolidates bylaws, governance policies, personnel rules, and operational guidelines.

Technology Integration

Technology is no longer just an operational tool; it is a governance asset.

- Email Systems: Use professional domains to maintain credibility and protect communications.

- Video Conferencing: Platforms like Zoom or Microsoft Teams enable inclusive participation, especially for geographically dispersed boards.

- Document Collaboration: Secure platforms such as SharePoint, Google Workspace, or BoardEffect support document sharing and version control.

- AI Tools: Deploy AI for donor data analysis, grant research, and compliance monitoring—while maintaining human oversight to guard against bias, privacy breaches, or misinterpretation of results.

Facilities, Maintenance, and Grounds

- Rental Management: For nonprofits owning property, establish fair, transparent policies for renting space to other organizations or the public.

- Maintenance Plans: Schedule preventive maintenance for facilities to avoid costly emergency repairs.

- Districting Considerations: For nonprofits with multiple locations, assign clear regional responsibilities and reporting structures.

Safety and Risk Management

- Physical Safety: Adhere to fire, health, and building safety codes; provide emergency preparedness training for staff and volunteers.

- Cybersecurity: Implement password protocols, data encryption, and regular security audits.

- Volunteer Safety: Establish guidelines for safe conduct during events and fieldwork.

Environmental Impact and Sustainability

Nonprofits have an opportunity—and often a moral imperative—to reduce their environmental footprint.

- Energy Efficiency: Upgrade to energy-saving lighting, HVAC systems, and appliances.

- Sustainable Procurement: Source materials from ethical, environmentally responsible suppliers.

- Waste Reduction: Implement recycling programs and reduce paper use through digital solutions.

Key Insight:

Practical operations are the proving ground for governance decisions. An organization that invests in sound administrative systems, modern technology, safe and sustainable facilities, and risk management not only functions more smoothly but also enhances its credibility with donors, regulators, and the communities it serves.

9. Continuous Learning & Governance Best Practices

Governance is not a static skill—it is a discipline that must adapt to new legal requirements, societal expectations, technological shifts, and organizational challenges. The best nonprofit boards cultivate a culture of continuous learning, where governance excellence is not only achieved but actively maintained.

Board Education

- Orientation: New board members should undergo structured onboarding that covers the mission, bylaws, fiduciary duties, current strategic plan, and financial position.

- Ongoing Training: Provide workshops, webinars, and reading lists on emerging topics such as AI in governance, diversity and inclusion, ESG reporting, and new regulatory requirements.

- Cross-Sector Exposure: Encourage board members to study governance models in other nonprofit sectors or even in the corporate sphere to bring in fresh perspectives.

Evaluation and Self-Assessment

- Board Assessments: Conduct annual evaluations of the board as a whole, assessing performance against goals and best practices.

- Individual Assessments: Invite members to reflect on their contributions, skills, and areas for growth.

- Committee Reviews: Periodically evaluate whether standing committees are fulfilling their mandates and contributing to strategic priorities.

Best Practice Frameworks

- Transparency: Publish annual reports, impact assessments, and audited financial statements.

- Stakeholder Engagement: Create open channels for feedback from donors, beneficiaries, and partners.

- Diversity and Inclusion: Actively recruit board members with varied backgrounds, skills, and lived experiences to ensure representative decision-making.

- Ethical Standards: Adopt and enforce clear policies on conflicts of interest, whistleblower protections, and responsible fundraising.

Learning from Others

- Peer Networks: Participate in national and regional nonprofit associations for shared learning and advocacy.

- Case Study Analysis: Review real-world examples of governance successes and failures to identify transferable lessons.

- External Advisors: Engage governance consultants or legal counsel for periodic reviews of bylaws, policies, and procedures.

Adaptation in the Age of Intelligence

Nonprofits in the current era must integrate new competencies into governance:

- Digital Literacy: Understanding the opportunities and risks of technology in operations and oversight.

- Scenario Planning: Preparing for rapid changes in funding, regulation, or public perception.

- Evidence-Based Decision-Making: Using data analytics to evaluate program impact and guide strategy.

Key Insight:

A nonprofit’s ability to learn is a leading indicator of its ability to thrive. Governance best practices are not a checklist to be completed—they are a continuous cycle of assessment, refinement, and renewal. Boards that embrace this ethos are better equipped to uphold their mission and adapt to the evolving environment in which they operate.

Conclusion

Nonprofit governance is a complex and dynamic discipline—rooted in centuries of civic tradition, yet constantly reshaped by social change, legal reform, and technological innovation. From ancient charitable trusts to modern global foundations, governance has always served as the bridge between mission and execution, ensuring that the resources entrusted to an organization are used ethically, effectively, and in alignment with its purpose.

The most effective nonprofit boards understand that governance is not simply an administrative obligation, nor a ceremonial function. It is an active practice of stewardship: setting direction, safeguarding resources, and holding the organization accountable to its mission and stakeholders. This requires clarity of role, strong systems, robust oversight, and a willingness to engage in both strategic foresight and operational detail.

In the Age of Intelligence, nonprofit governance faces new imperatives. Digital technologies and AI offer unprecedented tools for analysis, outreach, and efficiency—but they also bring risks of bias, security breaches, and over-reliance on automated systems. The governance task is to integrate these tools wisely, ensuring they serve human judgment and mission integrity rather than replace them.

Equally, the public expectations placed on nonprofits have expanded. Today’s stakeholders demand not only transparency and compliance, but measurable impact, diversity of leadership, environmental responsibility, and ethical fundraising. Meeting these expectations requires boards to be adaptable learners—engaging in continuous education, self-assessment, and a culture of improvement.

For the graduate student entering nonprofit leadership, and for the seasoned professional seeking to refine their governance practice, the lesson is the same: effective governance is a living discipline. It draws on history but is not bound by it; it respects tradition but is unafraid to innovate. It is both principled and pragmatic—grounded in fiduciary duties, yet responsive to the evolving needs of the communities it serves.

In the Science Abbey view, to govern a nonprofit well is to participate in a broader human project: creating institutions that channel collective resources toward the common good, sustain public trust, and adapt to the changing world without losing sight of their mission. This is the essence of nonprofit governance—and it is both an art and a science worthy of lifelong study and practice.

Appendix

Assessment Tools for Nonprofit Boards

These tools are designed to help boards evaluate their own performance, identify strengths and weaknesses, and set priorities for improvement. They can be used annually, during board retreats, or as part of orientation for new members.

1. Board Self-Assessment Checklist

Rate each item on a scale of 1 (Needs Improvement) to 5 (Excellent):

Mission and Strategy

- The board has a clear and concise mission statement.

- The board reviews and updates the strategic plan regularly.

- Strategic decisions are aligned with mission and long-term goals.

Governance and Leadership

- Roles and responsibilities of board members and officers are clearly defined.

- The board meets quorum requirements and follows bylaws consistently.

- There is a process for recruiting, onboarding, and evaluating board members.

Financial Oversight

- The board reviews accurate financial reports at each meeting.

- The organization maintains adequate reserves.

- There is a clear policy for gift acceptance and donor stewardship.

Compliance and Ethics

- The organization meets all filing and reporting requirements.

- Conflict-of-interest and whistleblower policies are in place and followed.

- The board promotes an ethical organizational culture.

Board Dynamics

- Meetings are well-organized and focus on strategic issues.

- Board members participate actively and constructively.

- Differences of opinion are handled respectfully and productively.

2. Officer and Committee Performance Review

Officer Evaluation

- Chair facilitates effective meetings and ensures follow-up on decisions.

- Treasurer provides accurate and comprehensible financial reports.

- Secretary maintains thorough, accessible records.

Committee Evaluation

- Each committee has a clear charter and meets regularly.

- Committees report progress to the full board in a timely manner.

- Committees’ work advances the organization’s strategic goals.

3. Governance Culture Survey

Use anonymous surveys to capture honest feedback from board members:

- How confident are you in the board’s decision-making process?

- Do you feel your contributions are valued and utilized?

- Does the board foster an inclusive and respectful environment?

- How well does the board hold itself accountable to its mission and stakeholders?

4. Meeting Effectiveness Rubric

Score each meeting on:

- Preparation: Were materials distributed in advance?

- Participation: Did all members have the opportunity to contribute?

- Focus: Did the meeting stay on agenda and on time?

- Outcomes: Were clear decisions made with assigned responsibilities?

5. Annual Governance Goals Worksheet

At the start of each year, set measurable goals in the following areas:

- Board development (training, recruitment, succession)

- Strategic plan milestones

- Fundraising targets and diversification of income

- Improvements to operations or technology

- Strengthening of community relationships

Key Insight:

Regular, structured assessment is not about fault-finding—it is about building a culture of continuous improvement. Boards that use these tools as part of their annual rhythm will strengthen their ability to lead with integrity, adapt to challenges, and deliver on their mission.