Table of Contents

Introduction – What Holds Civilization Together?

How infrastructure underpins modern life and reflects the values of society.

1. What Is Civil Engineering? – The Art and Science of Constructing Society

Definition, subdisciplines, and the evolving role of civil engineers in shaping the world.

2. Infrastructure – The Skeleton of Civilization

Categories of infrastructure (hard, soft, digital, green), their functions, and societal impact.

3. Scientific Foundations – Physics, Materials, Hydrology, and Beyond

The scientific disciplines that inform infrastructure design and engineering decisions.

4. Tools of the Trade – From Surveying to Simulation

Traditional and cutting-edge tools, including CAD, BIM, GIS, IoT, drones, and digital twins.

5. Infrastructure and Society – Urban, National, and Global Development

Infrastructure as a driver of human development across city, national, and international scales.

6. Education and Industry – Who Builds the World?

Training, licensing, top institutions, and the professional landscape of civil engineering.

7. Infrastructure and the Economy – Cost, Value, and Equity

How infrastructure investment shapes productivity, inequality, and development outcomes.

8. Infrastructure for the Future – Climate, AI, and Sustainability

Smart systems, climate resilience, circular design, and emerging green technologies.

9. Integrated Humanism and the Development Imperative

A values-based framework for equitable, sustainable infrastructure in a global context.

Conclusion – Foundations for a Wiser World

A call to build with wisdom, foresight, and a shared sense of responsibility for humanity’s future.

Introduction – What Holds Civilization Together?

We rarely stop to consider the quiet miracle of infrastructure. The road beneath our feet, the water in our taps, the lights that flicker on at night, the hospitals we rely on in crisis, and the networks that connect us across the globe—these are the hidden systems that sustain modern life. Beneath the apparent complexity of cities and nations lies a more fundamental architecture: civil engineering, the science and art of designing the physical frameworks of civilization.

Civil engineering is one of humanity’s oldest and most essential disciplines. It traces its roots to the first irrigation canals of Mesopotamia, the Roman aqueducts, the Great Wall of China, and the cathedrals of Europe. And it lives on in today’s skyscrapers, bridges, highways, flood defenses, tunnels, power grids, and data networks. While often overlooked, civil engineers are the stewards of society’s long-term functionality and safety.

Infrastructure, broadly defined, includes all the foundational systems that support economic activity, human health, and quality of life—from hard physical structures like roads and sewage systems to soft services like education, healthcare, and digital access. These systems do not exist in isolation; they intersect, evolve, and depend on each other. And without careful planning, maintenance, and innovation, they can collapse—sometimes literally.

Today, the world faces new challenges and opportunities. Climate change, urbanization, population growth, digital transformation, and widening inequality all demand a rethinking of how we build. But these are not merely technical issues—they are deeply human ones. Our infrastructures reflect our values, our priorities, and our ability to cooperate. In this way, civil engineering becomes more than a technical profession—it becomes a moral and civilizational task.

This article explores the full scope of civil engineering and infrastructure in the 21st century: the sciences and tools that make it possible, the industries and institutions that deliver it, the global challenges that shape it, and the emerging paradigm of Integrated Humanism—a philosophy that places reason, equity, sustainability, and human dignity at the heart of development.

As we look to the future, one thing is clear: to build a better world, we must first understand the one that holds us up.

Section 1: What Is Civil Engineering? – The Art and Science of Constructing Society

Civil engineering is the discipline responsible for designing, building, and maintaining the infrastructure that underpins all human civilization. It is one of the oldest branches of engineering, and one of the most expansive—covering everything from bridges and highways to dams, buildings, ports, and sanitation systems. Wherever people gather in large numbers, civil engineering is present: silently shaping the world we move through, depend on, and inhabit.

At its core, civil engineering is a synthesis of science and design. It uses physics, geology, hydrology, materials science, and mathematics to create structures that are not only functional and efficient, but safe, resilient, and durable. Civil engineers must think in decades, often centuries. Their work influences how societies evolve over generations.

A Legacy of Civilization

The origins of civil engineering are inseparable from the birth of complex societies. Ancient engineers built irrigation systems in Mesopotamia, pyramids in Egypt, road networks across the Roman Empire, and suspension bridges in Inca territories. These feats were not only marvels of ingenuity but vital to social cohesion, trade, governance, and cultural identity.

Modern civil engineering continues that legacy but faces new complexity. Today’s engineers must integrate traditional knowledge with advanced computing, sustainability metrics, digital modeling, and social impact assessments. They must build not only to last, but to adapt—to rising seas, shifting populations, and new technologies.

Core Subdisciplines of Civil Engineering

The field is typically divided into several core subdisciplines, including:

- Structural Engineering – Design and analysis of buildings, towers, bridges, and other load-bearing structures.

- Geotechnical Engineering – Understanding soils, rocks, and foundations to ensure ground stability and safety.

- Transportation Engineering – Planning and optimizing transport networks: roads, rails, airports, and public transit.

- Water Resources Engineering – Management of water through dams, canals, stormwater systems, and flood control.

- Environmental Engineering – Addressing waste, pollution, and sustainable systems for clean air and water.

- Construction Engineering and Management – The logistics, budgeting, and coordination of building projects.

- Urban and Regional Planning (in collaboration) – Designing entire cityscapes and long-term development zones.

These subfields often overlap and cooperate across scales—from neighborhood housing developments to national infrastructure strategies and global megaprojects.

The Civil Engineer’s Role Today

Civil engineers are more than technical problem-solvers. They are public servants, system designers, risk assessors, communicators, and ethical stewards. Whether working in governments, private firms, humanitarian organizations, or global partnerships, civil engineers must balance cost, time, safety, sustainability, and long-term societal value. Their choices shape how resources are distributed, how people live and move, and whether the built environment contributes to equity or exclusion.

In a rapidly changing world, civil engineers are not just building for today’s needs—they are laying the foundations for the future of humanity. Their work is measured not just in concrete and steel, but in opportunity, resilience, and hope.

Section 2: Infrastructure – The Skeleton of Civilization

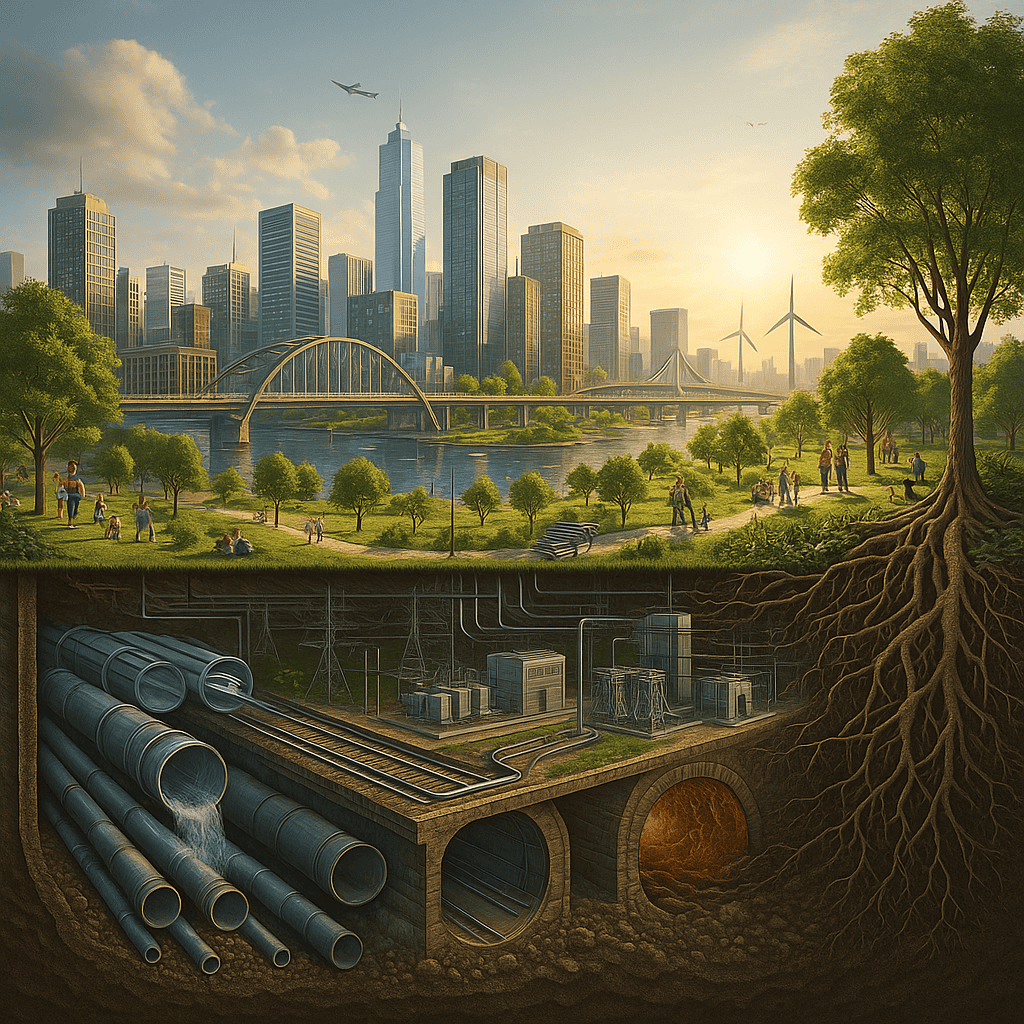

Infrastructure is the collective name for the systems and structures that allow a society to function. It is not always visible, but it is always vital—woven through every aspect of modern life. From the moment we wake and turn on the tap to the moment we ride an elevator, send a message, or cross a bridge, we are relying on infrastructure. It is the physical and organizational foundation upon which civilization stands.

Where civil engineering is the discipline that designs and maintains these structures, infrastructure is the outcome—the built reality that enables movement, communication, sanitation, power, safety, and social life.

Types of Infrastructure

To understand the full scope of infrastructure, it is helpful to categorize it into broad types:

1. Hard Infrastructure – The Physical Framework

This includes the engineered systems that transport people, materials, water, energy, and information. Examples:

- Transportation: Roads, highways, railways, subways, bridges, tunnels, airports, seaports

- Energy: Power plants, electric grids, transmission towers, oil and gas pipelines, wind and solar farms

- Water and Sewage: Reservoirs, water treatment plants, sewer systems, stormwater drains

- Telecommunications: Fiber optic cables, broadband networks, satellites, cell towers

- Waste Management: Landfills, recycling centers, incinerators, hazardous waste facilities

2. Soft Infrastructure – The Social Support Systems

This refers to the institutions and facilities that support education, health, culture, governance, and finance. Often built environments support these soft systems.

- Education: Schools, universities, research centers, vocational training institutes

- Healthcare: Hospitals, clinics, labs, emergency response systems

- Social Services: Government offices, community centers, post offices, libraries

- Financial Services: Banks, credit unions, ATMs, payment networks

- Recreation: Parks, sports complexes, theaters, museums

3. Emerging and Overlapping Types

As technology and environmental awareness evolve, so does our understanding of infrastructure:

- Digital Infrastructure: Data centers, cloud computing networks, IoT platforms, cybersecurity systems

- Green Infrastructure: Urban forests, wetlands, green roofs, bioswales—natural systems designed to provide ecological services

- Critical Infrastructure: Systems whose failure would paralyze society (e.g., power grids, hospitals, communications)

- Aviation and Space Infrastructure: Air traffic control, launchpads, runways, and satellite platforms

Why Infrastructure Matters

Infrastructure determines much more than convenience. It shapes:

- Economic productivity: enabling commerce, trade, and supply chains

- Health and sanitation: preventing disease and ensuring clean water

- Education and equity: connecting communities to opportunity

- Resilience: preparing for disasters, adapting to climate change, protecting populations

- National security and independence: safeguarding essential systems from foreign or cyber threats

But infrastructure also reflects values. Who gets clean water? Who has access to fast internet or safe public transit? Where are resources prioritized—or neglected? Infrastructure is a mirror of social justice, economic planning, and political intent.

Building and Maintaining the Skeleton

Designing infrastructure is only the beginning. Maintenance, upgrading, and strategic investment are constant needs. Decaying bridges, leaking pipes, and digital deserts are not signs of technological limits—they are signs of neglect, underfunding, or inequality.

As the global population grows and urban centers swell, infrastructure must be reimagined—smarter, greener, more inclusive, and more integrated. The challenge is not only to build more, but to build better.

Section 3: Scientific Foundations – Physics, Materials, Hydrology, and Beyond

Civil engineering is not merely a matter of drawing blueprints and pouring concrete. It is grounded in a vast and evolving body of scientific knowledge. Every road, dam, tunnel, or skyscraper stands because engineers have mastered the forces of nature and learned to work with—rather than against—the laws of the physical world.

Behind the physical elegance of great infrastructure lies a disciplined application of physics, chemistry, geology, environmental science, and mathematics. This section explores the scientific pillars that civil engineering stands on.

1. Physics – Forces, Loads, and Motion

Physics is the heart of structural and mechanical design:

- Statics and dynamics govern how structures bear weight and react to motion or vibration.

- Newtonian mechanics is essential for modeling how buildings and bridges respond to loads—dead loads (their own weight), live loads (traffic, people), and dynamic loads (wind, seismic forces).

- Fluid dynamics shapes the design of water systems, drainage, ventilation, and even aerodynamic structures like bridges and towers.

- Thermodynamics is critical in energy systems, heating/cooling design, and climate-adaptive infrastructure.

2. Materials Science – Strength, Durability, and Innovation

Every element of infrastructure must be built from the right materials for its function, environment, and lifespan. This science ensures safety and sustainability:

- Concrete, steel, asphalt, composites, and reinforced polymers are studied for properties like tensile strength, elasticity, corrosion resistance, and thermal behavior.

- Innovations in self-healing materials, geopolymers, and carbon-sequestering concrete promise greener, longer-lasting structures.

- Lifecycle analysis helps engineers understand the environmental and economic costs of materials from extraction to end-of-life.

3. Geotechnical and Earth Sciences – Building on the Ground

Civil engineers must understand the terrain they build on:

- Soil mechanics and rock physics are essential for evaluating how ground materials behave under pressure and in response to water.

- Seismic studies ensure buildings can withstand earthquakes.

- Slope stability, land subsidence, and frost heaving all influence infrastructure design in different climates and terrains.

- Hydrology helps predict flooding, manage water runoff, and design effective drainage and retention systems.

4. Environmental and Climate Sciences – Working with the Planet

Sustainability is now central to civil engineering. Engineers must consider how infrastructure interacts with ecosystems, air, water, and climate:

- Pollution control in air, soil, and water systems

- Climate modeling to design flood-resilient, heat-tolerant, and storm-ready infrastructure

- Greenhouse gas accounting for infrastructure-related emissions

- Ecosystem services provided by natural systems (like wetlands or forests) that can complement built solutions

5. Systems Science and Modeling – Complexity, Interdependence, and Planning

Modern infrastructure systems are deeply interconnected and dynamic. Engineers use:

- Mathematical modeling and computational simulation to forecast traffic patterns, structural stress, fluid flows, and population growth

- Systems thinking to design infrastructure that is resilient, adaptive, and integrated with other systems (e.g., transportation + energy + housing)

- Resilience engineering to anticipate failure modes and create redundancies

Civil engineering science is not static. It grows with every new material, climate pattern, population shift, and urban challenge. To practice infrastructure design today is to engage in a deeply interdisciplinary and forward-looking scientific endeavor—one that holds the future of civilization in its hands.

Section 4: Tools of the Trade – From Surveying to Simulation

From ancient rope-and-plumb-line techniques to today’s AI-assisted simulations, civil engineering has always advanced in step with the tools it uses. These tools are not simply instruments—they are extensions of the engineer’s mind, allowing for precision, foresight, and imagination in the design and management of the world’s infrastructure.

This section outlines the essential and emerging tools that civil engineers use at every stage of a project—from planning and design to construction, monitoring, and maintenance.

1. Traditional Tools – Still the Backbone

Many foundational tasks in civil engineering continue to rely on proven tools, especially in the field:

- Surveying Instruments: Theodolites, total stations, levels, and GPS equipment are used to measure distances, angles, and elevations with high accuracy.

- Construction Equipment: Cranes, bulldozers, pile drivers, concrete mixers, and paving machines remain essential for turning plans into physical reality.

- Material Testing Devices: Instruments like slump cones, compression testers, and soil shear boxes ensure the strength and stability of materials and foundations.

These tools provide the tactile, hands-on engagement with the built environment that remains crucial to the engineer’s role.

2. Digital Design – Modeling the World Before It Exists

Digital modeling has revolutionized civil engineering, enabling complex projects to be designed, tested, and revised in virtual environments:

- CAD (Computer-Aided Design): Allows engineers to draft detailed 2D and 3D models of structures, layouts, and systems.

- BIM (Building Information Modeling): Goes beyond CAD to integrate spatial, functional, cost, and lifecycle data into unified, interactive 3D models. BIM enables collaboration across disciplines and enhances long-term asset management.

- GIS (Geographic Information Systems): Essential for mapping, analyzing, and visualizing geospatial data—used in transportation planning, land development, disaster response, and environmental analysis.

These tools support scenario testing, coordination, and optimization, saving time, cost, and environmental impact.

3. Smart Infrastructure and Sensing Technology

Modern infrastructure doesn’t just sit still—it collects data and reports back:

- Embedded Sensors: Placed in bridges, roads, buildings, and pipelines to monitor stress, strain, temperature, vibration, and flow.

- IoT (Internet of Things): Networks of smart sensors allow for real-time monitoring of infrastructure health, energy use, and traffic.

- Drones and Robotics: Used for site inspection, surveying difficult terrain, or monitoring construction progress and post-disaster damage.

- Remote Sensing and LiDAR: High-resolution scanning tools provide detailed topography and surface data for planning and modeling.

These technologies help engineers detect failures before they happen, extend lifespans, and ensure safety in a rapidly changing world.

4. Project Management and Workflow Systems

A successful project depends as much on coordination and logistics as on design:

- Scheduling Software: Tools like Primavera and Microsoft Project manage timelines, milestones, and workforce allocation.

- Cost Estimation and BIM Integration: Platforms that combine design and finance streamline budgeting and procurement.

- Digital Collaboration Suites: Real-time platforms allow architects, engineers, contractors, and stakeholders to communicate and make joint decisions.

5. Emerging Frontiers – Simulation, AI, and the Digital Twin

Civil engineering is on the edge of a technological leap:

- Digital Twins: Virtual replicas of real infrastructure that integrate live data to simulate performance, test upgrades, and anticipate failures.

- AI and Machine Learning: Used to optimize traffic flow, predict material fatigue, model climate impacts, and automate design processes.

- Augmented Reality (AR): Engineers can overlay digital models onto real-world sites for planning, inspection, or training.

- Autonomous Equipment: Self-driving excavators and drones can perform repetitive or dangerous tasks with precision.

These advances are not just novelties—they are helping engineers build faster, cheaper, safer, and more sustainably.

In civil engineering, tools are more than equipment—they are expressions of our collective capacity to measure, model, and modify the world. As our challenges grow more complex and our ambitions more planetary, the tools of the trade will shape not just what we build, but how wisely we build it.

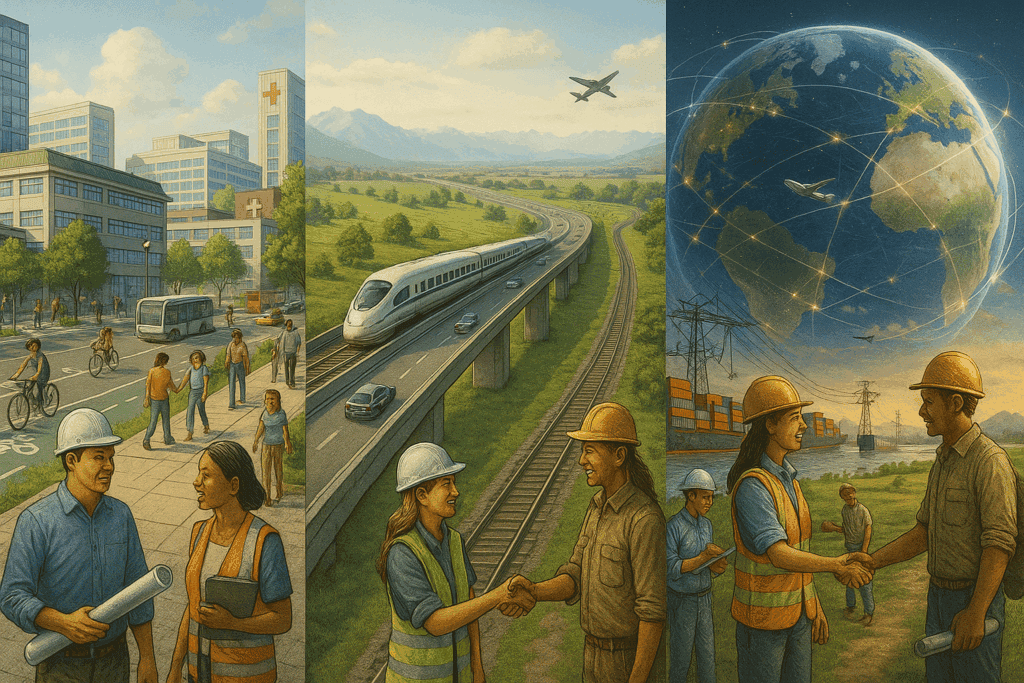

Section 5: Infrastructure and Society – Urban, National, and Global Development

Infrastructure is more than concrete and steel—it is a reflection of who we are and what we value. It shapes the daily lives of individuals, the productivity of nations, and the trajectory of global civilization. From the layout of a city block to the reach of a transcontinental railway, infrastructure is both a consequence and a catalyst of social development.

Civil engineers do not simply build in space—they build in society. This section explores how infrastructure operates at different levels: local, national, and planetary.

1. The Urban Scale – Cities as Engines of Civilization

Cities are where infrastructure is most concentrated—and most visible. Roads, transit, sewers, power lines, data cables, housing, and parks form the nervous system of urban life.

Civil engineers and urban planners work together to ensure:

- Mobility and connectivity through integrated transportation networks

- Water and waste management that can scale with population

- Affordable housing and equitable land use

- Public spaces that foster social cohesion and mental health

- Resilient infrastructure that can endure heatwaves, floods, and other climate impacts

The rise of “smart cities”—which use data and automation to improve services—is transforming urban infrastructure. But technology alone cannot solve issues of inequality, segregation, or neglect. People-centered design remains the foundation.

2. The National Scale – Infrastructure as Strategy

At the national level, infrastructure becomes a strategic asset:

- National highways and rail networks bind regions together.

- Energy grids and water systems power homes, farms, and factories.

- Airports, ports, and communication systems enable commerce and global integration.

- Public institutions—schools, hospitals, courts—require safe, accessible buildings and networks.

Governments must weigh long-term investment against short-term politics. The best national infrastructure policies:

- Prioritize regional equity, not just major cities

- Plan for intergenerational sustainability

- Encourage public-private partnerships while safeguarding public interests

- Integrate climate adaptation into every plan and budget

Infrastructure failure—from collapsed bridges to water crises—can cripple economies and erode public trust. Conversely, well-planned investment creates jobs, boosts GDP, and supports national resilience.

3. The Global Scale – Infrastructure in the Age of Interconnection

No nation builds in isolation. Infrastructure is now a global story, with enormous implications:

- International trade corridors like China’s Belt and Road Initiative reshape global supply chains

- Subsea internet cables and satellite constellations form a digital backbone for all modern economies

- Cross-border power grids and pipelines share resources and risks

- Development finance institutions like the World Bank fund infrastructure in lower-income nations

- Humanitarian engineering brings clean water, shelter, and mobility to refugee camps and disaster zones

Global infrastructure also raises ethical and environmental questions. Will new projects destroy ecosystems or protect them? Will they empower local communities or create dependency? Who benefits—and who pays?

The future demands a planetary perspective. Infrastructure must respond not just to national priorities, but to global needs: climate security, biodiversity protection, fair access to technology, and the rise of megacities across the Global South.

Infrastructure as a Social Contract

Ultimately, infrastructure is about trust. People must trust that the bridges they cross are safe, that the water they drink is clean, that their city will not flood, that their digital connections will not fail. Infrastructure is society made tangible—and its quality reflects our commitment to one another.

As cities grow, climates shift, and populations migrate, the challenge is not only to expand infrastructure, but to rethink it: not as a patchwork of projects, but as a living system of relationships, responsibilities, and shared destiny.

Section 6: Education and Industry – Who Builds the World?

Behind every bridge, building, pipeline, and port is a network of people: engineers, surveyors, architects, technicians, and managers—trained minds and capable hands who make civilization possible. Civil engineering is not just a body of knowledge or a set of tools; it is a living profession, carried forward by education, ethics, and industry.

This section explores how civil engineers are trained, certified, employed, and organized around the world, and how the profession evolves to meet the changing demands of society.

1. Educating the Engineer – From Foundations to Frontiers

A civil engineer’s journey begins with a strong foundation in mathematics, physics, and design. Undergraduate and graduate programs offer courses in:

- Structural analysis and design

- Fluid mechanics and hydrology

- Geotechnical and environmental engineering

- Materials science

- Construction management

- Systems engineering and sustainability

- Software and simulation (e.g., CAD, BIM, GIS)

The best programs balance classroom learning with fieldwork, lab testing, and capstone projects. Increasingly, they also incorporate climate resilience, social equity, and global ethics as core competencies.

Notable Schools for Civil Engineering (Global Perspective):

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) – USA

- ETH Zurich – Switzerland

- University of Cambridge – UK

- Tsinghua University – China

- National University of Singapore (NUS) – Singapore

- IIT Bombay / Delhi – India

- Delft University of Technology (TU Delft) – Netherlands

- University of Tokyo – Japan

- University of Melbourne – Australia

In the Global South, regional engineering schools are increasingly influential in shaping infrastructure development in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia.

2. Professional Certification and Ethics

Civil engineers carry heavy responsibilities. To safeguard the public, most countries require:

- Licensing or registration (e.g., PE in the US, CEng in the UK)

- Codes of ethics enforced by professional bodies

- Continuing education to stay updated on best practices and emerging risks

Ethical dilemmas in infrastructure—over budget allocation, safety margins, corruption, environmental impact—are not uncommon. Professional integrity is non-negotiable.

Major engineering institutions include:

- Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) – UK

- American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) – USA

- World Federation of Engineering Organizations (WFEO) – global coordination

- Engineers Australia, Engineering Council of India, and many national bodies

3. The Infrastructure Industry – Global Builders

The civil engineering sector is vast and global, spanning:

- Consulting Firms: Design, planning, and project management (e.g., Arup, AECOM, WSP)

- Construction Giants: Large-scale project execution (e.g., Bechtel, Vinci, China Communications Construction Company)

- Public Infrastructure Agencies: National transport, utilities, housing, and disaster response

- Development Organizations: NGOs and international bodies like UN-Habitat and Engineers Without Borders

The best companies invest in R&D, diversity, environmental stewardship, and international collaboration. As infrastructure becomes smarter and greener, they are hiring not only engineers, but also data scientists, environmental specialists, and AI developers.

4. Labor, Diversity, and Inclusion

Engineering has long struggled with diversity—especially gender, race, and class inclusion. Change is underway:

- Scholarships, mentorships, and outreach programs target underrepresented groups.

- Inclusive workplace design (e.g., for fieldwork safety and flexibility) is improving retention.

- Cross-cultural training supports global teamwork in multinational projects.

The future of infrastructure depends on attracting the brightest minds—from all communities, and with a shared commitment to justice and sustainability.

Civil engineering education and industry must evolve with the challenges of our time. A new generation of engineers is emerging—one that is globally aware, technologically fluent, ethically grounded, and passionately committed to building a better world.

Section 7: Infrastructure and the Economy – Cost, Value, and Equity

Infrastructure is often measured in kilometers, megawatts, or tons of concrete—but its true value is economic, social, and long-term. Civil infrastructure is not only an expense; it is an investment. It enables commerce, creates jobs, unlocks opportunity, and lays the foundation for prosperity. Yet without strategic planning and equitable access, infrastructure can just as easily entrench inequality or waste public funds.

This section examines how infrastructure influences the economy—from the balance sheet to the social contract.

1. Infrastructure as Economic Engine

Investing in infrastructure stimulates economic activity in multiple ways:

- Direct employment during construction and maintenance

- Supply chain stimulation for materials, machinery, and services

- Increased productivity from reduced travel times, energy losses, or service disruptions

- Improved connectivity leading to stronger regional and global trade

- Urban growth through higher land values and better real estate development

For every dollar spent, studies estimate that well-planned infrastructure can return 1.5 to 3 times its value in GDP growth—especially in emerging economies where basic systems are underdeveloped.

2. Public vs. Private Infrastructure – Who Builds and Pays?

Infrastructure is traditionally seen as a public good, financed and maintained by governments. But rising costs and shrinking public budgets have led to:

- Public-private partnerships (PPPs): Joint ventures where private firms finance, build, and sometimes operate public infrastructure

- User-fee models: Tolls, fares, or service charges that recoup costs from beneficiaries

- Privatization of utilities or transport systems in some countries

- Sovereign infrastructure funds and bonds for long-term investment

While these models can increase efficiency and leverage private capital, they must be carefully managed to avoid inequality, overpricing, or neglect of non-profitable (but essential) projects like rural water or low-income housing.

3. Maintenance, Renewal, and the Cost of Neglect

Building is only the beginning. Without ongoing maintenance, infrastructure decays:

- In the U.S. alone, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) has estimated that delayed infrastructure repair could cost the economy trillions by 2040 in lost productivity, vehicle damage, and reduced competitiveness.

- Developing countries face even greater risks when rapid urbanization outpaces system capacity.

Deferred maintenance is politically convenient but economically disastrous. Infrastructure investment must include life-cycle planning, with transparent accounting for future repair, resilience upgrades, and decommissioning.

4. Infrastructure Inequality – Who Gets What?

Not all communities benefit equally. Infrastructure often favors:

- Wealthier urban centers over rural or underserved areas

- Private vehicle users over public transit riders

- Commercial zones over residential neighborhoods

- Majority populations over marginalized groups

This spatial and social inequality affects:

- Access to jobs, schools, and healthcare

- Exposure to environmental risks (e.g., poor flood defenses, waste sites)

- Digital divides and the uneven reach of broadband and cellular networks

Inclusive infrastructure design must center equity as a planning principle, not an afterthought.

5. Global Disparities and Development Priorities

Globally, infrastructure gaps remain a major barrier to development:

- Over 2 billion people lack safely managed drinking water

- Nearly 800 million lack reliable electricity

- Hundreds of millions live without safe roads, schools, or hospitals

The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) call for massive investment in clean energy, transport, sanitation, and digital infrastructure—especially in Africa, South Asia, and underserved urban regions.

Infrastructure investment is not charity—it is the economic foundation for a fairer global future.

Infrastructure is not merely about what we build, but for whom, with what values, and at what long-term cost. It is a mirror of economic policy, and a lever for inclusive prosperity—or continued disparity.

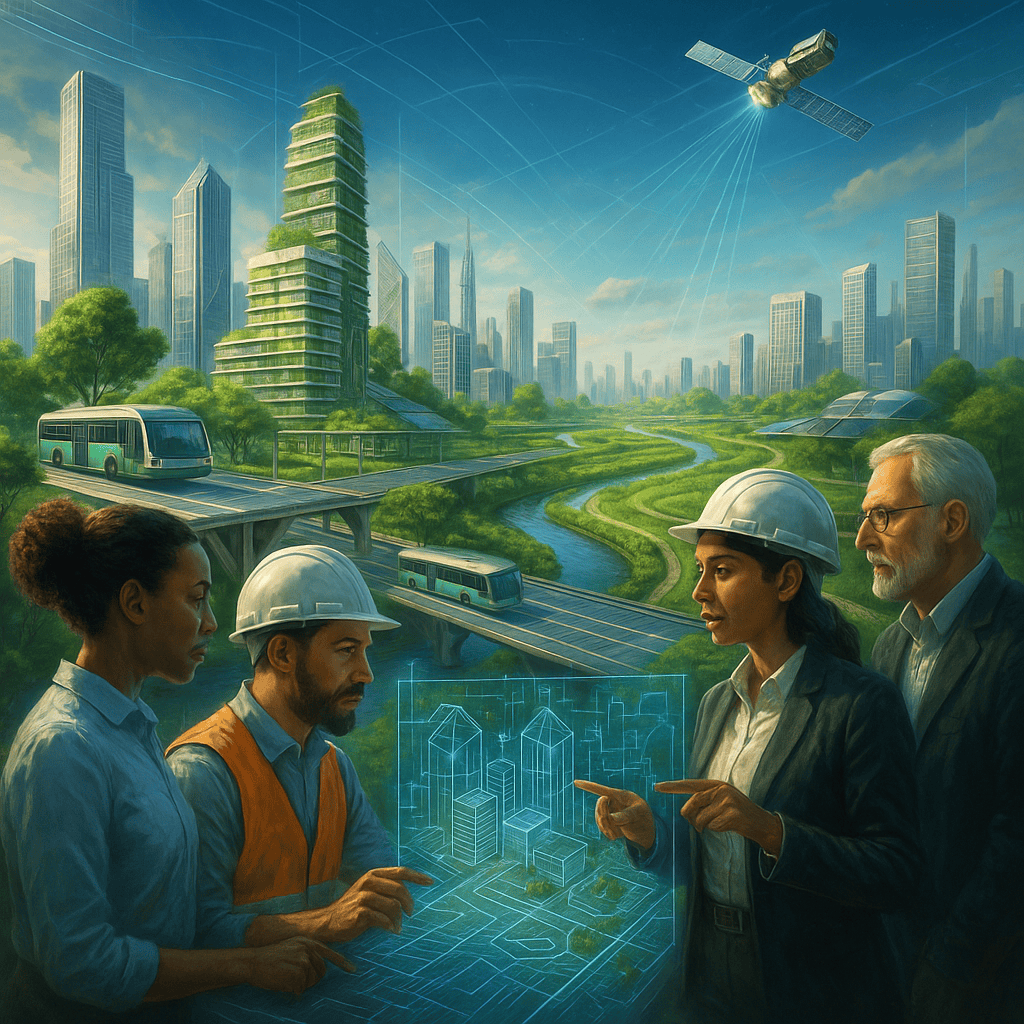

Section 8: Infrastructure for the Future – Climate, AI, and Sustainability

As the 21st century unfolds, infrastructure is being tested by forces unprecedented in human history—climate volatility, technological disruption, mass urbanization, and ecological collapse. The civil engineering profession now stands at a crossroads: to repeat the patterns of the industrial age, or to pioneer a new era of sustainable, intelligent infrastructure that serves both people and planet.

This section examines how future infrastructure must evolve—scientifically, technologically, and morally.

1. Climate-Resilient Infrastructure – Adapting to a Changing Planet

The climate crisis is already reshaping infrastructure needs:

- Flood defenses in low-lying cities

- Cooling systems for heatwave-prone regions

- Storm- and fire-resistant buildings

- Flexible energy grids to handle renewable surges and outages

- Migration-ready urban design to accommodate displaced populations

Climate-resilient infrastructure must be designed not just to endure past weather patterns, but to anticipate instability. This includes using dynamic modeling, future climate scenarios, and nature-based solutions like wetlands and permeable pavements.

2. Decarbonization and Circular Design

The built environment accounts for an estimated 40% of global CO₂ emissions, including emissions from:

- Cement and steel production

- Construction logistics and machinery

- Energy usage in buildings and facilities

Solutions include:

- Low-carbon concrete and alternative materials

- Modular and prefabricated construction to reduce waste

- Circular infrastructure that designs for reuse, disassembly, and material recovery

- Passive design for energy efficiency in buildings

Tomorrow’s infrastructure must not only withstand climate change—it must help prevent it.

3. Smart Infrastructure – Data-Driven, Automated, Responsive

Digital intelligence is now embedded in physical infrastructure:

- Sensor arrays monitor real-time stress, energy use, and water levels

- AI algorithms optimize traffic flow, structural maintenance, and energy distribution

- Digital twins provide living simulations of bridges, neighborhoods, and transit networks

- Autonomous machines perform inspections, repairs, and construction

Smart systems offer efficiency—but they also raise new challenges of privacy, cybersecurity, algorithmic bias, and dependency. Responsible design and public oversight are critical.

4. The Fusion of Nature and Technology – Green-Blue Infrastructure

The future is not only concrete and silicon. It is also soil, water, and trees:

- Urban forests and green roofs cool cities and reduce runoff

- Blue infrastructure—rivers, lakes, and wetlands—provides flood resilience and biodiversity

- Eco-bridges reconnect wildlife corridors

- Biomimicry inspires infrastructure modeled on nature’s time-tested patterns

Civil engineering is embracing a deeper ecological intelligence, seeing cities as part of a living system.

5. Global Cooperation and Ethical Futures

To build a just and sustainable world, future infrastructure must be:

- Globally coordinated, not just nationally competitive

- Ethically governed, with transparency, justice, and long-term vision

- Accessible to all, especially underserved populations and regions

- Designed with humility, recognizing that every structure alters ecosystems, cultures, and futures

The infrastructure of the future must serve not only human progress, but the survival of life itself.

In a time of converging crises and accelerating change, the infrastructure we build today is the legacy we leave for the next century. Civil engineers, planners, scientists, and citizens must come together to imagine and realize a resilient, low-carbon, intelligent, and compassionate civilization.

Section 9: Integrated Humanism and the Development Imperative

At the deepest level, infrastructure is a moral choice. Every road, bridge, school, and sewer reflects a decision about who deserves access, what kind of society we want, and how we relate to the Earth. In this way, civil engineering is not only a technical discipline—it is a form of applied ethics, a material expression of our values.

Integrated Humanism offers a framework for infrastructure that prioritizes the long-term flourishing of all people and the planet. It is a secular, science-based, and democratic worldview that places human dignity, equity, and sustainability at the center of development.

1. Infrastructure as a Human Right

In a just world, no one should live without clean water, safe shelter, transportation, healthcare access, or digital connection. Integrated Humanism argues that basic infrastructure is a birthright, not a luxury:

- Clean drinking water

- Sanitation and waste management

- Electrification and internet access

- Schools and clinics within reach

- Climate-resilient housing and transit

These are not utopian dreams. They are achievable goals—if backed by political will, inclusive planning, and equitable resource allocation.

2. Democratic Planning and Public Participation

Top-down megaprojects often overlook the needs of the communities they are meant to serve. Integrated Humanist development calls for:

- Participatory infrastructure design

- Community consultation and feedback mechanisms

- Open data on budgets, contracts, and performance

- Transparency and accountability in both public and private sectors

Democracy in development means not just voting, but co-creating the world we live in.

3. Evidence-Based, Science-Led Design

Every aspect of infrastructure—location, materials, systems, maintenance—should be guided by the best available science:

- Climate models and ecological studies

- Epidemiology and public health

- Traffic analytics and behavioral data

- Economic modeling and risk forecasting

Science is not an obstacle to development—it is the foundation of responsible development. Integrated Humanism insists on decisions rooted in data, not dogma or short-term profit.

4. Ethical Engineering and the Global Common Good

Engineers working within this paradigm are not merely builders, but stewards of:

- Social equity

- Intergenerational justice

- Environmental sustainability

- Global solidarity

Whether building a school in Nairobi, a wind farm in Norway, or a metro in São Paulo, the underlying goal is the same: to contribute to a global civic infrastructure where every person has a fair chance to live well.

5. The Development Imperative – Building Toward Human Maturity

Civilization is not static—it evolves. Infrastructure shapes that evolution. Integrated Humanism envisions a planetary future in which:

- Cities are carbon-neutral, green, and livable

- Villages are connected and dignified, not left behind

- Infrastructure is resilient to climate, conflict, and displacement

- The built environment enhances human potential, not just economic output

The question is not whether we will build—but how, and for whom. And whether we will build with wisdom enough to match the stakes of our age.

In this light, civil engineering becomes not only a profession, but a civic duty and a philosophical calling. It asks each generation: What kind of world will you leave behind?

Conclusion – Foundations for a Wiser World

Civilization is not built in a day—and never by accident. Behind every functioning society lies a foundation of deliberate design: roads that carry us, structures that shelter us, systems that nourish, protect, and connect us. Civil engineering and infrastructure are not just technical feats—they are the backbone of human progress.

Yet in this century of rising temperatures, swelling cities, and shifting global power, that backbone is under stress. Old systems are crumbling. New demands are emerging. And with them comes a once-in-a-generation opportunity—not merely to repair the past, but to reinvent the future.

This article has explored how civil engineering shapes cities, nations, and the planet. It is rooted in physics and data, constructed with machines and materials, guided by education and ethics. But more than that, it is driven by purpose. And that purpose must now evolve—from expansion to integration, from exploitation to stewardship, from short-term growth to long-term wisdom.

Integrated Humanism offers a compass: to build sustainably, to plan justly, to engineer with compassion and foresight. It calls for a global architecture of dignity—where infrastructure is not a battleground of profit, but a shared framework for human flourishing.

To build that world requires more than money or machines. It requires courage. Collaboration. Vision. And an unwavering commitment to the idea that every person, everywhere, deserves access to the systems that make life safe, meaningful, and free.

The next century will not be judged by how much we built—but by how wisely we built it.