Table of Contents

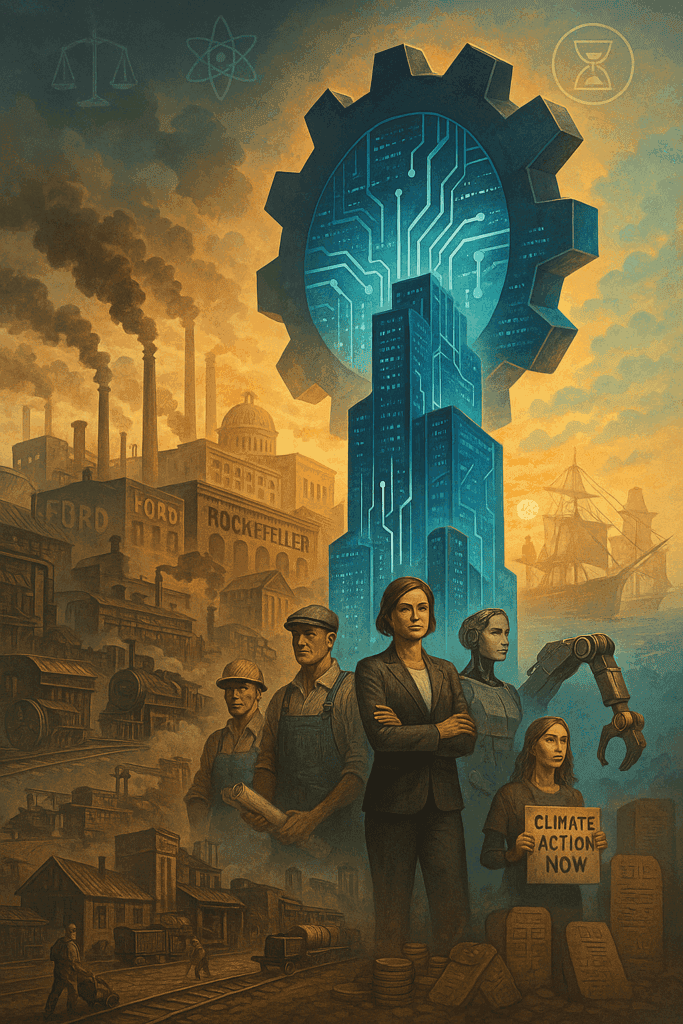

1. Introduction – The Engine of Civilization

How production and corporations became the defining institutions of the modern world.

2. Philosophies of Production and Economic Theory

From Adam Smith to degrowth: the ideas that shape economic life.

3. Evolution of Corporate Structures

The rise of firms—from chartered companies to platform giants.

4. Business Leaders and Theorists Who Changed the World

Thinkers and entrepreneurs who redefined economics, industry, and society.

5. Corporate Organization and the Science of Management

Finance, governance, data systems, and the internal mechanics of modern firms.

6. The Global Corporate Landscape Today

An overview of the largest firms, industries, and regional models of business power.

7. Corporate Power and Political Influence

How firms shape policy, evade taxes, and influence democracy.

8. Financial Institutions and Oversight Mechanisms

Stock markets, watchdogs, Islamic finance, and the architecture of accountability.

9. Challenges in Business Today

Inequality, automation, ESG, surveillance, and reputational risk.

10. Integrated Humanist Corporate Principles

A blueprint for ethical, sustainable, and accountable enterprise.

11. Conclusion – Corporations and the Human Future

Reimagining corporate purpose in an age of planetary and social urgency.

1. Introduction – The Engine of Civilization

No invention has shaped modern civilization quite like the corporation. From textile mills in 18th-century Britain to the algorithm-driven platforms of Silicon Valley, the machinery of production—industrial, financial, and digital—has grown in scale, scope, and consequence. Corporations have become not only engines of economic growth but key actors in geopolitics, technology, and public life.

At its core, production is the conversion of inputs into outputs. But as societies evolved, so too did their means of organising this transformation. Trade guilds gave way to joint-stock companies; factories to global supply chains; clerks to cloud-based data models. Today’s multinationals—some with budgets exceeding those of sovereign states—coordinate labour and capital across continents with the precision of code and the opacity of law.

None of this emerged in a vacuum. The intellectual scaffolding was laid by economic thinkers—Smith, Marx, Keynes—whose theories were tested, distorted, or embraced by successive waves of industrialists, from Carnegie to Jobs. The corporation, for all its abstraction, remains a deeply human creation, subject to ambition, ideology, and error.

The present landscape is both remarkable and fraught. Technology firms dominate capital markets. Fossil-fuel giants hedge into renewables. Luxury brands and pharmaceutical firms compete for influence in developing economies. Meanwhile, questions multiply: Who truly benefits from growth? What constitutes corporate responsibility? Can shareholders, stakeholders, and the planet coexist peacefully?

This article traces the evolution of production and corporations, from philosophical foundations to present-day structures of power. It examines the science behind corporate organisation—finance, management, information systems—and the politics surrounding taxation, regulation, and influence. It surveys the world’s major corporate powers by region and sector, and concludes with a look ahead: toward a model of corporate life that aligns profit with purpose.

If the corporation is the defining institution of the modern world, then understanding it—its logic, limits, and potential—is not just useful. It is imperative.

2. Philosophies of Production and Economic Theory

Production is not merely a technical activity—it is a political and philosophical one. Every economic system, from slave economies to platform capitalism, rests on ideas about what people value, how resources should be distributed, and who deserves a share of the surplus. Theories of production, once the preserve of moral philosophers, now underpin everything from taxation regimes to central bank policy.

The Classical Tradition: Wealth and the Invisible Hand

In 1776, Adam Smith set the tone for modern economic thought. In The Wealth of Nations, he proposed that individuals, by pursuing their own gain, could unintentionally contribute to the good of all. This so-called “invisible hand” became a guiding metaphor for market economies. Smith favoured competition and the division of labour, but he was no radical libertarian: he saw a role for state intervention in public goods and education.

The classical school—Smith, Ricardo, Malthus—laid the foundation for thinking about productivity, capital accumulation, and comparative advantage. Their influence endures in arguments for free trade and lean government.

Karl Marx and the Industrial Backlash

The Industrial Revolution did not produce only coal smoke and railways—it also generated discontent. Karl Marx, writing in the mid-19th century, offered a full-throated critique of capitalism. For Marx, production was not neutral: it was the terrain of class conflict. He argued that workers, alienated from the fruits of their labour, were exploited for surplus value by the owners of capital.

While the prescriptions of Marxism fared poorly in most real-world implementations, the critique of inequality and exploitation remains relevant. In periods of crisis—from the Gilded Age to the gig economy—Marx’s voice tends to echo louder.

Keynes, Friedman, and the Modern State

The 20th century saw a sharp divergence in economic thought. In the wake of the Great Depression, John Maynard Keynes rejected the notion that markets are self-correcting. His remedy: counter-cyclical government spending to stabilise demand. Keynesianism dominated post-war economic policy in much of the West and underpinned the welfare state.

Later, in the inflation-plagued 1970s, a counter-revolution emerged. Milton Friedman and the Chicago School revived faith in market discipline, central bank independence, and monetarism. Deregulation, privatisation, and tax cuts followed, ushering in the neoliberal era. Proponents credit these policies with restoring growth; critics blame them for rising inequality and financial instability.

Behavioural Economics and the Human Mind

Classical economics, for all its elegance, assumed rational actors. Reality proved messier. The late 20th and early 21st centuries have witnessed the rise of behavioural economics, which draws from psychology to explain why people often act against their own best interest. Concepts like loss aversion, bounded rationality, and “nudges” have found their way into policymaking and corporate strategy alike.

Behavioural insights complicate the tidy diagrams of neoclassical models. They also challenge the assumption that consumers and investors are always best left alone.

Beyond Growth: Sustainability and Degrowth

As ecological limits loom larger, a new generation of thinkers has begun to question growth itself. Post-growth and degrowth theorists argue that constant expansion is incompatible with planetary boundaries. They advocate for metrics beyond GDP—well-being, resilience, ecological balance—and for economic systems that prioritise long-term survival over short-term profits.

These views remain on the margins of mainstream economics but are gaining traction in climate policy circles and among younger economists wary of business as usual.

3. Evolution of Corporate Structures

Corporations, like cities or states, are inventions designed to solve problems of scale. At their best, they enable humans to coordinate production, investment, and risk across time and distance. At their worst, they become unaccountable behemoths, insulated by legal fictions and driven by short-term returns. Their evolution reflects shifting balances of power—between state and market, capital and labour, innovation and regulation.

From Guilds to Charters

In the medieval world, production was organised at the local level. Guilds regulated trades, maintained standards, and often limited competition. These were not corporations in the modern sense but early forms of collective economic governance.

The true precursors of today’s corporations were the chartered companies of early modern Europe. Entities like the British East India Company and the Dutch VOC were granted monopolies and legal rights by the state in exchange for expanding imperial trade. These organisations wielded private armies, issued shares, and—in some cases—governed entire territories. They demonstrated both the power and the peril of corporate autonomy.

The Rise of the Joint-Stock Company

By the 19th century, the joint-stock company had become a common instrument of industrial capitalism. Ownership was divided into transferable shares, risk was dispersed, and capital could be raised at scale. The corporate form allowed enterprises to survive beyond their founders and operate with legal personhood.

Limited liability, formalised in Britain in 1855, made investing less risky and accelerated corporate growth. Railways, steelworks, and textile mills expanded into regional and national monopolies. Shareholders profited; workers, often, did not.

Managerial Capitalism and the Technostructure

In the 20th century, as corporations grew ever larger, ownership and control began to diverge. Shareholders became dispersed, and professional managers took the reins. Theorists like Alfred Chandler and John Kenneth Galbraith observed the rise of a “technostructure”—an internal bureaucracy of experts, engineers, and executives wielding de facto power.

This was the golden age of the vertically integrated firm. Giants like General Motors, IBM, and AT&T managed everything from production to marketing in-house. Lifetime employment and generous benefits became common in some countries, particularly Japan and post-war America.

Globalisation and the Rise of the Multinational

By the late 20th century, advances in transport, communications, and trade liberalisation enabled corporations to become global. Manufacturing dispersed to low-cost regions; headquarters remained in financial centres. Supply chains grew longer, and tax strategies more intricate.

Multinational corporations (MNCs) became both engines of development and lightning rods for criticism. Accused of undermining labour rights, avoiding taxes, and hollowing out domestic industries, MNCs also provided jobs, introduced technology, and spurred investment. Their power now rivals that of many governments.

The Platform Era and Beyond

In the 21st century, a new type of corporate entity has emerged: the platform firm. Companies like Amazon, Google, Alibaba, and Meta do not just produce goods—they organise markets. They act as digital infrastructure, extract data, and mediate transactions between billions of users.

Their value lies less in tangible assets and more in algorithms, ecosystems, and attention. The platform model has created new dependencies, blurred regulatory boundaries, and raised urgent questions about monopoly, privacy, and democratic oversight.

4. Business Leaders and Theorists Who Changed the World

The evolution of production and corporations has been shaped not just by systems but by individuals—some economists, others industrialists, a few cultural icons. These figures have introduced the theories, methods, and enterprises that define how the modern world works. Their influence stretches across boardrooms and factory floors, policy papers and popular imagination.

4.1 Philosophers of the Economic Order

Adam Smith

The Scottish moral philosopher laid the intellectual foundation for market economies in The Wealth of Nations (1776). Smith argued that self-interest, channelled through competition and specialisation, leads to collective prosperity. Though often cited by laissez-faire advocates, he also acknowledged the need for state involvement in education, infrastructure, and public goods.

Karl Marx

A rival to Smith in influence, if not in popularity among capitalists, Marx cast production as a battleground of class struggle. In Das Kapital, he introduced the concept of surplus value and portrayed capitalism as inherently exploitative and crisis-prone. While his solutions proved politically volatile, his critique still animates debates on inequality and labour rights.

John Maynard Keynes

Keynes revolutionised macroeconomics by arguing that governments must step in to stabilise economies during downturns. His ideas reshaped post-war policy, underpinning the welfare state and full-employment economics. Though eclipsed by free-market orthodoxy in the late 20th century, Keynesianism returned to favour after the global financial crisis.

Milton Friedman

A leader of the Chicago School, Friedman championed monetarism and minimal government. He was instrumental in the neoliberal turn of the 1980s, advocating for deregulation, privatisation, and the primacy of shareholder value. For better or worse, many central banks now operate within a framework shaped by his ideas.

4.2 Industrial Titans and Empire Builders

Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller

Both rose from modest origins to dominate American steel and oil, respectively. Carnegie championed vertical integration and philanthropy; Rockefeller, standardisation and scale. Their empires spurred antitrust legislation, but their business methods—efficiency, consolidation, and hard bargaining—remain textbook lessons in industrial strategy.

Henry Ford

Ford’s innovations in assembly-line production and wage policy made mass production viable and workers into consumers. His $5-a-day wage was both a marketing tool and a social experiment. Fordism became a byword for 20th-century industrial capitalism: productive, hierarchical, and durable.

Warren Buffett

The “Oracle of Omaha” built Berkshire Hathaway into a sprawling conglomerate with a cult-like following. Buffett’s investment philosophy—value-oriented, long-term, and understated—stands in contrast to the volatility of modern finance. His shareholder letters are studied like scripture in business schools.

4.3 Entrepreneurs of the Digital Age

Steve Jobs and Bill Gates

Jobs brought design, branding, and technological intuition together to reinvent consumer electronics. Gates scaled Microsoft into a near-monopoly on PC software. Both helped define the personal computing era—Jobs with flair, Gates with ubiquity. Their influence transcends commerce and touches on how people learn, work, and communicate.

Jeff Bezos and Satya Nadella

Bezos redefined retail through Amazon, turning logistics into a competitive weapon and cloud computing into a growth engine. Nadella, meanwhile, is credited with revitalising Microsoft—shifting its focus from software licensing to cloud services, AI, and enterprise tools. Both exemplify the modern executive: global in scope, data-driven, and algorithmically inclined.

4.4 Toward a New Ethic of Business

Oprah Winfrey

Though not a theorist or industrialist, Winfrey built a media empire through personal branding, narrative control, and emotional intelligence. Her career reflects the growing convergence of celebrity, entrepreneurship, and identity in modern capitalism.

Modern ESG and Behavioural Thinkers

A new cohort of thinkers—among them Cass Sunstein, Richard Thaler, and Rebecca Henderson—are reframing corporate purpose. Behavioural economists highlight cognitive biases and the limits of rational choice; ESG advocates push for environmental, social, and governance standards that go beyond profit maximisation.

This emerging synthesis suggests a subtle shift in corporate philosophy—from pure shareholder primacy to a more complex calculus of risk, reputation, and responsibility.

5. Corporate Organization and the Science of Management

Behind every successful enterprise lies an architecture of decisions—how to allocate capital, structure teams, manage risk, and adapt to change. While founders and CEOs receive public attention, the internal machinery of the corporation is often more decisive. Over time, managing firms has become not only an art, but a science—one shaped by disciplines as diverse as accounting, psychology, computer science, and systems engineering.

5.1 Corporate Governance and Leadership Structures

The modern corporation typically features a board of directors overseeing management on behalf of shareholders. But models vary: American firms often separate the roles of CEO and chairman (in theory, if not always in practice), while German companies implement codetermination, requiring worker representation on supervisory boards. In Japan, consensus and seniority still dominate, though reforms are nudging boards toward independence.

Leadership remains a contested domain. Some favour charismatic founders with sweeping control; others advocate for decentralised, data-driven decision-making. The “imperial CEO” model has not vanished, but it faces new checks—from activist investors, regulators, and sometimes employees.

5.2 Accounting, Finance, and Auditing

Double-entry bookkeeping, developed in Renaissance Italy, still underpins corporate accounting. But the modern finance department is a far cry from dusty ledgers. Today’s CFO oversees complex valuation models, tax strategies, risk assessments, and regulatory disclosures. International standards—like IFRS and GAAP—govern financial reporting, while auditors act as third-party validators.

Scandals—from Enron to Wirecard—have exposed the limits of self-regulation. Calls for greater transparency and independent oversight continue to shape the profession, especially as investors demand more data on non-financial risks such as climate exposure.

5.3 The Role of Information Technology

Once relegated to back-office operations, IT is now central to corporate life. Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems coordinate procurement, finance, HR, and logistics. Customer relationship management (CRM) platforms turn data into marketing leverage. Cybersecurity, cloud migration, and digital transformation are now board-level concerns.

Increasingly, companies view themselves not just as producers of goods or services, but as platforms for information flows. This shift is particularly visible in finance, logistics, and e-commerce, where real-time data enables just-in-time delivery and hyper-targeted pricing.

5.4 Artificial Intelligence and Business Intelligence

AI is reshaping corporate operations. Machine learning algorithms predict consumer behaviour, optimise supply chains, detect fraud, and screen job candidates. Natural language processing powers chatbots and virtual assistants. Predictive analytics enables dynamic pricing and demand forecasting.

Yet AI also introduces new risks—algorithmic bias, black-box decision-making, and regulatory uncertainty. Firms that fail to understand the ethical and legal implications may find short-term gains offset by long-term liability.

5.5 Organisational Psychology and Systems Thinking

The human side of management remains vital. How employees are motivated, how teams collaborate, and how culture evolves inside a firm can determine success as much as capital and code. Insights from behavioural science—on incentive structures, cognitive biases, and group dynamics—are increasingly used to refine corporate strategy.

Systems thinking, meanwhile, offers a broader lens. It encourages leaders to consider feedback loops, interdependencies, and long-term consequences—particularly relevant in large, complex organisations navigating volatile environments.

6. The Global Corporate Landscape Today

Corporations today are not merely economic actors—they are geopolitical forces, cultural icons, and sometimes, political gatekeepers. A handful of firms control vast swathes of global trade, communications, logistics, and data. They shape not only what consumers buy, but how societies think, vote, and govern. While their formal structures differ across jurisdictions, their reach is increasingly planetary.

6.1 The World’s Largest Corporations

Measured by revenue, market capitalisation, or brand value, the same names recur. In 2025, firms like Apple, Saudi Aramco, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, and Tencent dominate global rankings. Some control networks of users (Alphabet, Meta); others command physical supply chains (Walmart, Shell); still others, like BlackRock and Vanguard, operate from the shadows—controlling trillions in passive investment funds and holding stakes in most public companies.

The global top 500, as tracked by Fortune, reveals a familiar pattern: concentration of corporate power in a handful of sectors—tech, finance, energy, healthcare, and manufacturing—and a gradual shift toward Asia, especially China.

6.2 Industry Breakdown: Key Sectors

- Technology: Dominated by U.S. and Chinese firms. The U.S. leads in consumer tech and semiconductors; China in digital infrastructure and super apps. Europe remains a regulatory superpower but a commercial laggard. India is emerging as a global hub for software services and digital payments.

- Finance: Global finance is shaped by a small cohort of banks (JPMorgan Chase, ICBC, HSBC), asset managers (BlackRock, State Street), and insurers (Allianz, Ping An). Cryptocurrencies and fintech firms are challenging legacy models, but systemic control remains with regulated giants.

- Energy and Resources: Oil majors (ExxonMobil, Aramco, Sinopec) still top revenue lists, though they now invest heavily in renewables. Mining conglomerates like BHP and Rio Tinto underpin the energy transition through rare earth extraction. ESG pressure is growing—but patchily enforced.

- Consumer Goods and Retail: From Unilever to Procter & Gamble, global brands now coexist with direct-to-consumer challengers. Amazon and Alibaba dominate e-commerce. Fast fashion and fast food remain highly profitable, and highly scrutinised.

- Healthcare and Pharma: Firms like Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, and Roche wield both scientific and political influence. The COVID-19 pandemic expanded their prominence—and their profit margins. Debates over pricing, access, and patents remain unresolved.

6.3 Ownership Structures and Legal Forms

Corporations vary by ownership and governance. Publicly traded firms dominate headlines, but private equity, state-owned enterprises, family-run conglomerates, and cooperatives remain influential. The rise of B-Corps and benefit corporations reflects growing demand for mission-driven alternatives.

In China, most “private” firms operate under state direction. In Europe, family firms retain influence (e.g., Bosch, Heineken). In the U.S., the venture-backed startup-to-IPO pipeline continues, though consolidation is rising. Hybrid forms are multiplying, as firms experiment with dual-class shares, stakeholder trusts, and embedded social goals.

6.4 Regional Profiles

- United States: Home to the most valuable firms and the deepest capital markets. American corporations benefit from scale, weak antitrust enforcement, and deep integration with global finance. The tech sector, in particular, wields considerable lobbying power.

- China: A distinct hybrid. Firms like Huawei and Tencent are nominally private but operate within strict state parameters. The CCP’s influence is explicit, and the corporate sector is tightly aligned with national goals—from AI dominance to supply-chain resilience.

- European Union: Regulatory sophistication, but commercial fragmentation. The EU excels in antitrust enforcement, privacy regulation, and green finance—but struggles to foster global champions. Family businesses and SMEs remain the backbone of the continental economy.

- India: Rapidly expanding digital economy, anchored by service firms like Infosys and Tata Consultancy. Government initiatives (e.g., Digital India, Atmanirbhar Bharat) aim to elevate manufacturing and tech sovereignty.

- United Kingdom: Post-Brexit, the UK is repositioning itself as a nimble financial centre and biotech hub. London remains a key node for global finance, though regulatory divergence from the EU introduces uncertainty.

- ASEAN: A diverse bloc. Singapore leads in finance and logistics; Indonesia and Vietnam are rising manufacturing powers. Regional integration remains partial, but intra-ASEAN investment is growing.

- Islamic Finance Regions: Sharia-compliant finance offers an alternative logic—avoiding interest, favouring profit-sharing. Gulf states and Malaysia have built parallel financial architectures, including sukuk (Islamic bonds) and zakat-linked corporate responsibility schemes.

7. Corporate Power and Political Influence

Corporations do not merely operate within political systems—they help shape them. Through campaign finance, lobbying, legal engineering, and strategic hiring, large firms influence the policies that govern markets, labour, taxation, and even democracy itself. In many countries, the line between public and private power is increasingly porous.

7.1 Campaign Finance and Lobbying

In the United States, political contributions are a well-established feature of corporate strategy. Since the Supreme Court’s Citizens United ruling in 2010, companies (and their proxies) have gained expansive rights to fund political campaigns. Super PACs and dark money groups now funnel billions into elections, often without full transparency. Industries from fossil fuels to pharmaceuticals deploy lobbying budgets that dwarf the spending of many public-interest organisations.

Europe maintains stricter controls, though lobbying remains robust in Brussels. In emerging economies—India, Brazil, South Africa—corporate influence often flows through opaque networks of patronage, regulatory leniency, and media ownership.

In China, the mechanism is reversed: firms gain power through alignment with the Communist Party. Party committees are embedded in many large corporations. Influence is real but state-mediated.

7.2 The Revolving Door

The practice of officials moving between government and industry—often with generous compensation—has become routine. Former regulators become corporate advisors; ex-ministers join boards; central bankers pivot to asset management firms. While defenders cite the value of experience, critics point to regulatory capture and conflicts of interest.

This “revolving door” phenomenon is especially visible in finance, pharmaceuticals, defence, and tech—sectors where insider knowledge is both lucrative and difficult to regulate.

7.3 Taxation and Global Avoidance

Corporate tax avoidance is not a loophole—it is a global industry. Multinationals shift profits through shell companies, transfer pricing, and intra-firm loans. Intellectual property rights are routinely parked in low-tax jurisdictions like Ireland, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Singapore, or island territories.

Efforts to curtail such practices are ongoing. The OECD’s “Base Erosion and Profit Shifting” (BEPS) initiative, and the G20-backed global minimum tax framework, aim to impose baseline tax rates on global profits. Yet enforcement is inconsistent, and political will varies by country.

Public frustration is growing. When trillion-dollar firms pay lower effective tax rates than small domestic businesses, legitimacy erodes.

7.4 Public Disclosure and Accountability

Listed companies are subject to mandatory disclosures—annual reports, quarterly filings, and, in some jurisdictions, ESG-related data. But opacity remains common, particularly in private equity, family holdings, and supply chains.

“White sheets” and 10-K filings offer technical data, but often fail to capture off-balance-sheet risks, tax strategies, lobbying expenditures, or social impacts. Shareholder activism, whistleblowers, and investigative journalism continue to fill the gaps—but often only after damage is done.

7.5 Case Studies in Influence

- Big Tech in the U.S.: Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, and Apple spend heavily in Washington and Brussels. Their lobbying touches antitrust, privacy, labour rights, and AI regulation.

- Energy and Fossil Fuels: ExxonMobil and Shell, once climate skeptics, now position themselves as transition leaders—while quietly funding think tanks opposed to emissions regulation.

- Pharma and Patents: During the COVID-19 pandemic, vaccine makers resisted calls to waive IP protections, despite receiving billions in public subsidies.

- Media and Influence: In many markets, media ownership by conglomerates introduces subtle—or overt—bias into coverage of business and regulation.

8. Financial Institutions and Oversight Mechanisms

Behind the visible world of corporations lies a scaffolding of institutions—stock exchanges, rating agencies, development banks, Islamic finance bodies, and watchdog organisations—each playing a role in maintaining (or manipulating) economic order. These institutions determine the rules of engagement, enforce compliance—when they can—and increasingly, shape the moral vocabulary of global business.

8.1 Securities Markets and Public Disclosure

Stock exchanges remain the gateway to capital for large firms. New York, London, Tokyo, Hong Kong, and Shanghai host the world’s most active stock markets, facilitating trillions in daily transactions. Listing requirements vary, but generally include audited financials, governance standards, and periodic reporting. Exchanges serve not only as platforms for raising capital, but as instruments of national prestige and geopolitical rivalry.

Market confidence depends on transparency, but that confidence is fragile. The 2008 global financial crisis and high-profile frauds (e.g., Enron, Wirecard, Luckin Coffee) revealed the limits of self-policing. In response, regulators have demanded greater detail in annual reports—particularly regarding ESG risks and climate exposure—but enforcement lags aspiration.

8.2 Multilateral Institutions: From IMF to WEF

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank play dual roles: as stabilisers of national economies and as conduits for global corporate penetration. Their structural adjustment programmes have long attracted criticism for prioritising deregulation and privatisation—often favouring foreign investors at the expense of domestic industries.

The World Economic Forum (WEF), best known for its annual Davos meeting, operates more as an elite networking node than a regulatory force. It promotes stakeholder capitalism, digital innovation, and public-private partnerships, but critics see it as a talking shop for the global elite—more spectacle than substance.

The OECD, WTO, and BIS contribute more quietly, coordinating tax policy, trade rules, and central banking standards. They shape the architecture in which corporations operate—even if their democratic legitimacy is often questioned.

8.3 Islamic Financial Systems

Islamic finance, grounded in Sharia law, forbids interest (riba), promotes ethical investment, and encourages profit-sharing over debt. Institutions such as the Islamic Development Bank, AAOIFI, and regional financial centres in Bahrain, Dubai, and Kuala Lumpur oversee a growing array of instruments—sukuk (Islamic bonds), halal funds, and zakat-linked corporate responsibility frameworks.

Though still a minority within global finance, Islamic models appeal to investors seeking value-aligned portfolios and to governments in Muslim-majority countries seeking financial sovereignty. Some Western banks now offer Sharia-compliant products to access these markets.

8.4 Labour Unions and Worker Representation

Once a counterweight to corporate power, labour unions have been weakened in much of the developed world. In the U.S., union membership in the private sector has dropped below 7%. In the UK and parts of Europe, collective bargaining persists, but varies by sector. In Germany and Scandinavia, co-determination and works councils give workers a formal role in governance.

Globally, informal labour dominates—especially in emerging markets. The International Labour Organization (ILO) pushes for fair labour standards, but enforcement is left to national governments and voluntary corporate pledges. Gig economy workers remain largely unrepresented.

New efforts—such as platform cooperatives, employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs), and transnational union alliances—aim to reconfigure worker agency in the digital age.

8.5 Consumer Protection and Corporate Watchdogs

Consumer protection varies widely. In the EU, strict regulations cover product safety, digital rights, and data privacy (notably the GDPR). The U.S. offers more fragmented protections, with agencies like the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) pursuing litigation more than regulation.

Watchdog NGOs—such as Transparency International, Tax Justice Network, and Corporate Accountability—monitor corruption, tax avoidance, and greenwashing. While their influence is limited, their reports often inform journalists, activist investors, and regulatory agendas.

Credit rating agencies (S&P, Moody’s, Fitch), ESG score providers, and financial data firms (Bloomberg, MSCI) wield enormous influence but face criticism for opacity, conflicts of interest, and inconsistent methodologies.

9. Challenges in Business Today

Modern corporations operate in a world of unprecedented complexity. Global supply chains, digital platforms, political volatility, and ecological limits have expanded the responsibilities—and the liabilities—of business. Public expectations have shifted from mere compliance to active leadership on social and environmental issues. Yet the incentives that drive corporate behaviour remain stubbornly anchored to short-term profitability.

9.1 ESG: Rhetoric and Reality

Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria have moved from fringe concern to boardroom agenda. Large firms now issue sustainability reports, hire chief sustainability officers, and integrate ESG metrics into investor communications. Asset managers like BlackRock publicly embrace ESG frameworks.

Yet greenwashing remains endemic. Many firms tout climate pledges while continuing high-emissions operations. ESG ratings are inconsistent, often based on self-reported data. Some critics accuse ESG of being less a moral framework than a marketing strategy, designed to placate regulators and attract capital without fundamentally altering business models.

9.2 Automation, AI, and Inequality

Advances in automation and artificial intelligence promise efficiency but threaten widespread job displacement. Routine work—clerical, logistical, manufacturing—is increasingly done by machines. White-collar professions are next, with generative AI encroaching on legal, journalistic, and even managerial roles.

While firms benefit from lower costs and higher productivity, the societal costs—underemployment, reskilling gaps, wage stagnation—are externalised. The risk is a widening chasm between capital and labour, exacerbated by declining union power and rising returns to intellectual property.

9.3 Supply Chain Vulnerability and Ethics

COVID-19, climate disasters, and geopolitical tensions have exposed the fragility of global supply chains. Just-in-time models, while lean, are brittle. Disruptions in a single port or region can cascade across continents.

Moreover, supply chains are riddled with ethical hazards—from child labour in cobalt mines to forced labour in textiles. Transparency initiatives and blockchain traceability tools have emerged, but uptake remains uneven and accountability diffuse.

9.4 Corporate Surveillance and Data Misuse

In the digital economy, data is the new currency—and the new frontier of abuse. Tech giants harvest, monetise, and sometimes lose vast quantities of personal information. Targeted advertising, algorithmic discrimination, and opaque moderation policies raise difficult questions about privacy, autonomy, and corporate responsibility.

Regulators have begun to respond—through GDPR, California’s CCPA, and pending AI legislation in the EU—but enforcement is patchy and firms remain several steps ahead.

9.5 Reputational Risk and Activist Pressure

Corporations today are vulnerable not just to regulators, but to public backlash. Boycotts, viral scandals, and employee revolts can damage brands and derail leadership. Stakeholders now include not only investors and consumers, but NGOs, journalists, and increasingly, the firm’s own workforce.

Brand values, corporate purpose, and political positioning are no longer optional. They are strategic choices with financial consequences. Silence, too, can be interpreted as a stance.

10. Integrated Humanist Corporate Principles

If corporations are to remain legitimate in the 21st century, they must evolve beyond narrow shareholder primacy and embrace a broader social mandate. Integrated Humanism—a philosophy that unites scientific rationality with ethical responsibility—offers a foundation for this evolution. It envisions corporations not simply as profit engines, but as institutions of public trust, sustainability, and human development.

10.1 From Shareholder to Stakeholder

The Integrated Humanist view rejects the idea that corporations exist solely to maximise shareholder value. Instead, it promotes a multi-stakeholder model: shareholders, yes, but also employees, consumers, local communities, suppliers, ecosystems, and future generations.

This model requires embedding responsibility into the design of the firm. Boards must reflect diverse interests. Incentives should align long-term purpose with short-term performance. Public benefit must be measurable, not rhetorical.

10.2 Open Governance and Transparency

Opacity breeds corruption. Integrated Humanism demands open accounting: not only financial results, but social, environmental, and governance impacts—audited and accessible. Algorithmic decision-making, especially in finance, insurance, and hiring, must be explainable and accountable.

Supply chains should be traceable. Tax strategies should be public. Political contributions should be disclosed. Privacy should be a right, not a cost-benefit variable.

Technology can aid this transparency: distributed ledgers for traceability, real-time dashboards for emissions, and open-source ESG standards. But political will and institutional culture matter more.

10.3 Ethical Production and Environmental Stewardship

An Integrated Humanist corporation cannot externalise environmental costs. It must internalise planetary boundaries, operate within a carbon budget, and design for circularity. Planned obsolescence is an ethical failure; regenerative design is the future.

Resource use should be efficient, equitable, and future-conscious. Biodiversity, water, air, and soil—often ignored in corporate spreadsheets—must be valued as essential capital.

10.4 Labour Dignity and Participatory Structures

Work is not a cost centre—it is a human endeavour. Fair wages, humane scheduling, safe environments, and lifelong learning are minimum obligations. Firms must also provide voice: through unions, co-determination, cooperatives, or new forms of worker representation.

Integrated Humanism promotes “shared leadership”—structures where decision-making is distributed, and strategic intelligence flows both upward and downward. In a world of automation, the role of work must be reimagined as a path to purpose, not merely survival.

10.5 Regulation as Partnership, Not Opposition

Corporations often treat regulation as an obstacle. An Integrated Humanist perspective sees government as a co-steward of public welfare. Smart regulation can level playing fields, prevent race-to-the-bottom dynamics, and safeguard common goods.

Rather than lobbying for exemptions, corporations should participate in policy innovation—co-developing frameworks for carbon accounting, digital ethics, tax justice, and labour standards. Voluntary codes of conduct are not enough.

11. Conclusion – Corporations and the Human Future

For better or worse, the corporation is the most powerful institutional form of the modern era. More nimble than states, more permanent than parties, more resourced than most NGOs, corporations shape how people work, live, consume, and even vote. Their actions reverberate through supply chains, markets, ecosystems, and cultures.

Historically, corporations have delivered staggering progress: life-saving drugs, global communications, mass access to consumer goods, and technological marvels once confined to science fiction. But they have also deepened inequality, degraded the environment, manipulated politics, and undermined trust. Their legacy is mixed—and unfinished.

The next chapter depends not on the abolition of corporations, but on their transformation. Governance models must be revised to reflect broader accountability. Production systems must shift from extraction to regeneration. Profit must remain a goal—but never the sole purpose.

An Integrated Humanist vision insists that corporations, like any social institution, must serve human flourishing and planetary health. This means designing incentives that reward long-term thinking; embedding ethics into technology; giving workers voice, consumers choice, and communities a stake.

In an age of AI, climate disruption, and geopolitical tension, the question is not whether business can be ethical—but whether it can afford not to be.

The corporation of the future will not be defined merely by market share or innovation. It will be judged by what it builds—and what it preserves.