How We Extract, Refine, and Use Earth’s Resources—Responsibly

Table of Contents:

- Introduction – The Human Need for Earth’s Resources

The role of mining in modern civilization and the Integrated Humanist framework for responsible stewardship. - What We Extract – A Catalog of Earth’s Valuable Resources

Overview of metals, minerals, fossil fuels, and their uses in society. - How We Extract – Major Mining Methods

Surface mining, underground mining, in-place mining, dredging, and their variations. - Processing Earth’s Wealth – From Ore to Usable Materials

Step-by-step guide to mineral processing: crushing, grinding, separation, flotation, leaching, and purification. - Impacts of Mining – Environmental, Social, and Economic

Positive and negative effects of extraction and processing on people and planet. - Toward Sustainable Mining – Technology, Policy, and Ethics

Innovations in robotics, cleaner energy, waste reduction, and ethical labor practices. - The Future of Mining – A Vision of Integrated Humanist Stewardship

Balancing development with preservation through science, ethics, and long-term planning. - Conclusion – Responsible Resource Use in the Age of Intelligence

How mining fits into a human future guided by knowledge, compassion, and global cooperation.

1. Introduction – The Human Need for Earth’s Resources

Since the dawn of civilization, humanity has drawn from the Earth’s crust to build, create, and thrive. The stones that shaped our temples, the metals that forged our tools, and the fuels that powered our industries have all come from below our feet. Mining—often unseen and underappreciated—has been essential to nearly every facet of progress, from shelter and sanitation to smartphones and space travel.

But as our capacity to extract has grown, so too have the consequences. Mountains have been leveled, rivers poisoned, air polluted, and communities displaced. At the same time, mining has driven economies, provided livelihoods, and delivered the materials on which healthcare, clean energy, and infrastructure depend.

In an age of global interconnectedness and scientific awareness, the question is no longer whether we mine—but how. How do we extract the Earth’s resources without destroying the very systems that sustain life? How do we build a future that is materially rich, ethically sound, and ecologically viable?

This guide offers an Integrated Humanist perspective on mining—one that recognizes the necessity of resource extraction while demanding responsibility, wisdom, and foresight in how it is carried out. It surveys the key materials we mine, the standard extraction and processing methods, the impacts on the planet and its people, and the technologies and values needed to ensure that mining serves not only our present needs, but our shared human future.

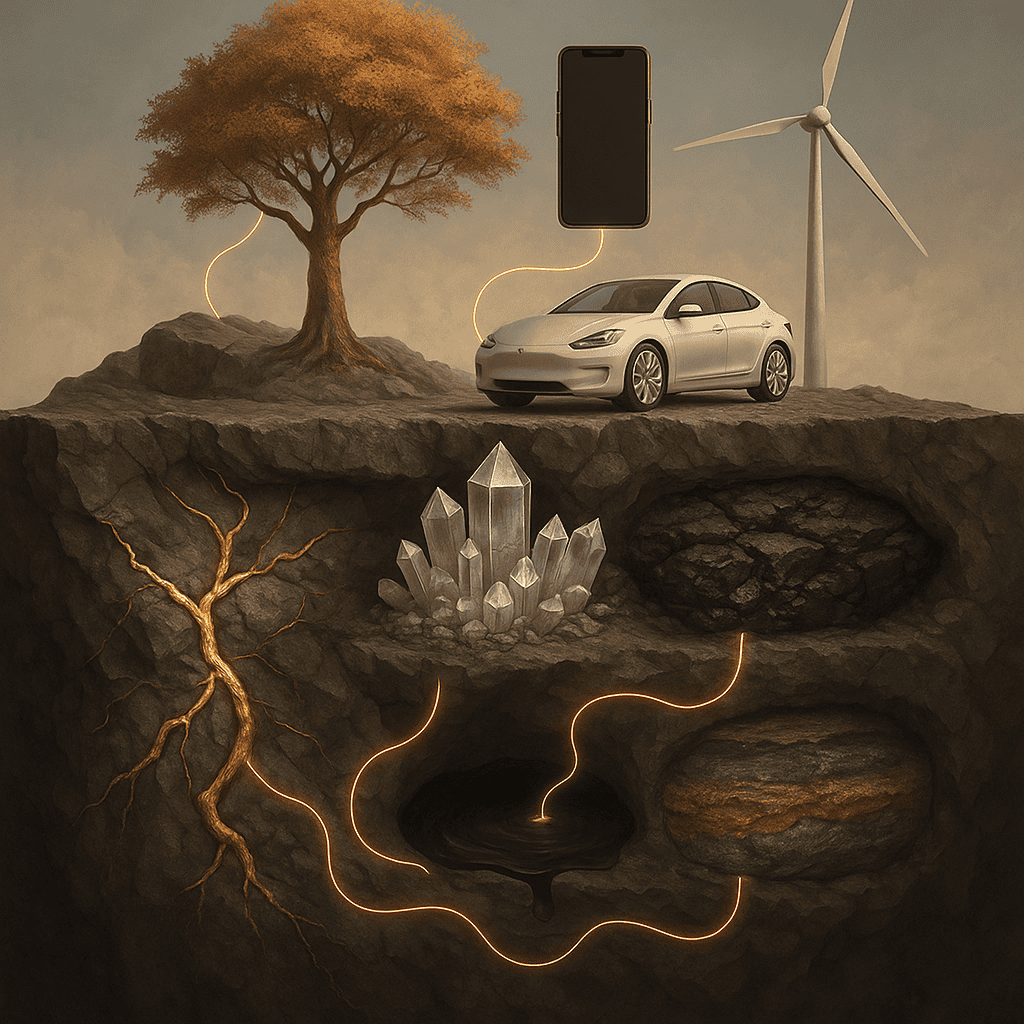

2. What We Extract – A Catalog of Earth’s Valuable Resources

Mining is not limited to gold and coal. The modern world relies on a vast spectrum of materials hidden within the Earth—each serving a critical role in our industries, economies, and daily lives. Understanding what we extract helps clarify why mining persists, and why ethical oversight and sustainable practices are essential.

1. Metals

Metals form the backbone of technology and infrastructure. Many are refined into pure elements; others serve as key alloys or conductors.

- Iron – Foundations, steel structures, vehicles, tools

- Copper – Electrical wiring, electronics, plumbing

- Aluminum – Lightweight structures, packaging, aerospace

- Gold & Silver – Electronics, jewelry, monetary reserves

- Nickel, Chromium, Cobalt, Zinc – Batteries, alloys, corrosion resistance

- Rare Earth Elements – Magnets, lasers, wind turbines, smartphones

2. Non-Metallic Minerals

These minerals are just as vital, though less flashy, supporting agriculture, energy, and construction.

- Limestone – Cement, roads, pH regulation

- Gypsum – Plaster, drywall, fertilizer

- Phosphates – Agricultural fertilizers

- Potash – Fertilizer, soaps, glass

- Clay & Sand – Ceramics, glass, construction materials

- Gemstones – Jewelry, abrasives, technology applications

3. Fossil Fuels

Although their future is contested, fossil fuels remain central to the global economy—for better and worse.

- Coal – Energy production, steel manufacturing

- Crude Oil – Transportation fuels, plastics, chemicals

- Natural Gas – Heating, electricity, fertilizers, hydrogen production

4. Water and Brines (Special Cases)

Though not traditionally “mined,” certain fluids are extracted using mining-like methods.

- Lithium Brines – Rechargeable batteries, electric vehicles

- Salt & Mineral Waters – Industry, food, health products

- Geothermal Fluids – Renewable energy from underground heat

Each resource plays a role in shaping society, from nourishing crops to electrifying homes. But all come with extraction costs—environmental, social, and ethical—that demand thoughtful regulation and sustainable innovation.

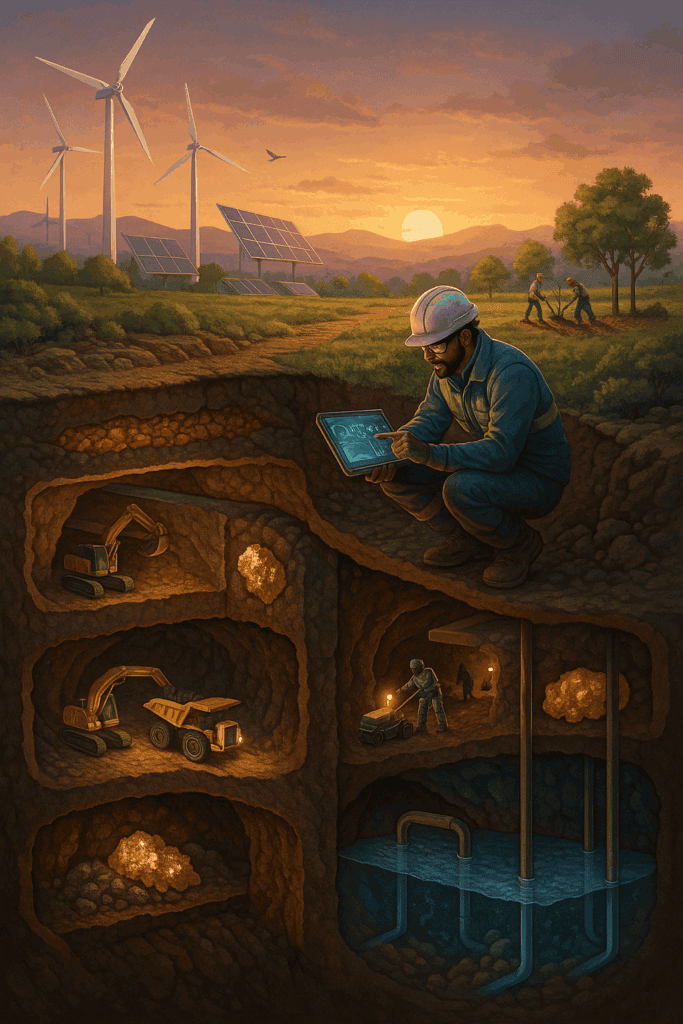

3. How We Extract – Major Mining Methods

The art and science of mining lie in the ability to reach and remove valuable materials from within the Earth. Different materials require different strategies. Extraction methods vary widely depending on geology, depth, environmental conditions, and economic feasibility—but they all involve disrupting natural formations to gain access to what lies beneath.

Below are the principal methods used in modern mining:

1. Surface Mining

This method removes overlying soil and rock (called overburden) to expose mineral deposits close to the surface.

- Open-Pit Mining – A stepped excavation, used for metals like copper and gold. Large-scale, cost-effective, but visually and ecologically destructive.

- Strip Mining – Used for coal and tar sands. Involves stripping large areas of land, often resulting in habitat loss and erosion.

- Mountaintop Removal – A form of strip mining where entire mountain tops are blasted away—highly controversial for its environmental toll.

2. Underground Mining

Used to access deeper mineral veins, this method involves drilling shafts and tunnels below the surface.

- Room and Pillar – Horizontal passages with support pillars, common in coal and salt mining.

- Longwall Mining – A mechanical shearer removes large blocks, while roof supports prevent collapse.

- Block Caving – Allows controlled collapse of ore bodies for efficient mass extraction.

Underground mining has a smaller surface footprint, but often poses higher risks to workers and complex engineering challenges.

3. In-Place Mining (In-Situ Recovery)

Instead of digging, this method extracts minerals by dissolving them underground and pumping the solution to the surface.

- Solution Mining – Common for uranium, lithium, and potash. Minimizes surface disturbance but risks groundwater contamination.

4. Dredging

Used to extract mineral-rich sediments from underwater environments like rivers, lakes, and seafloors.

- Suction Dredging – Draws slurry from riverbeds or ocean floors.

- Bucket Dredging – Mechanically scoops material from underwater deposits.

Dredging is useful for marine mining and gold panning but can severely disrupt aquatic ecosystems.

Each method reflects a balance between technological capability, cost, and environmental impact. In the next section, we’ll see what happens after extraction: the industrial alchemy of transforming raw ore into usable products.

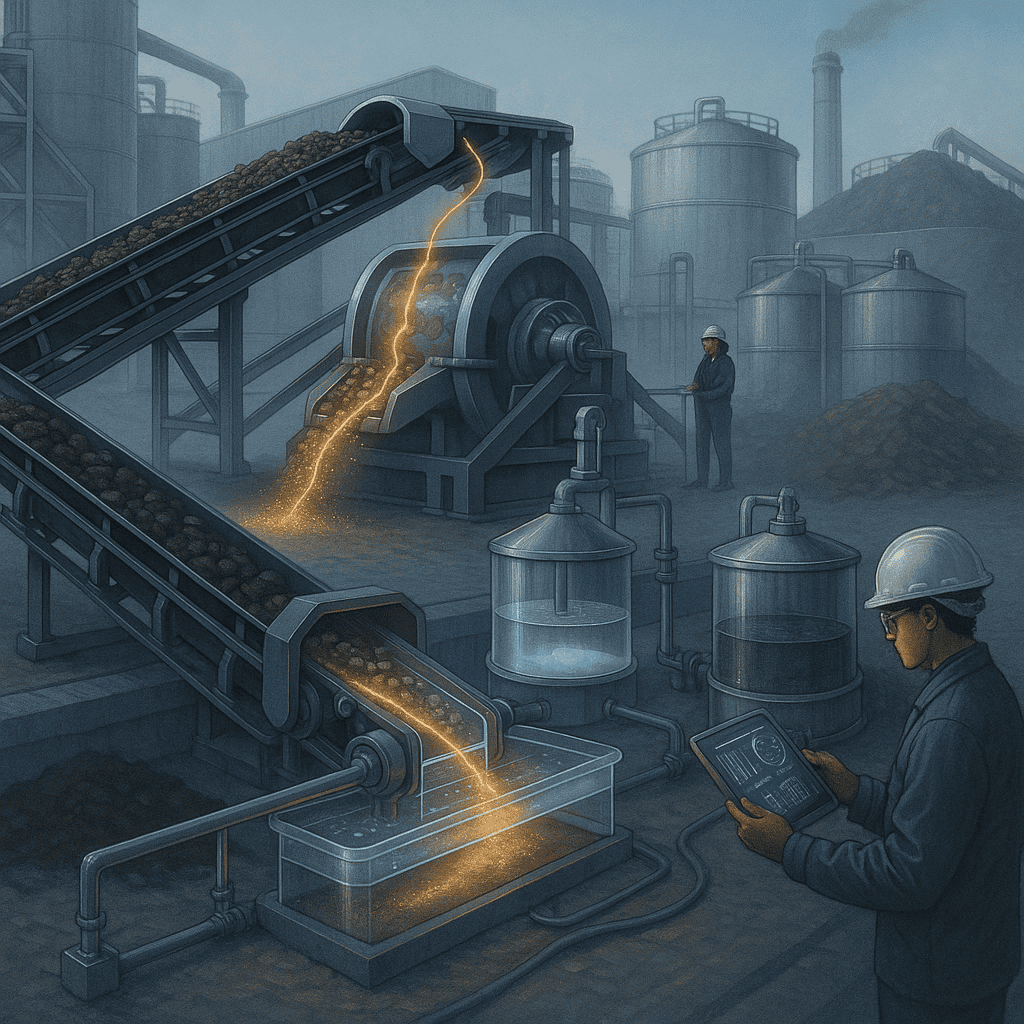

4. Processing Earth’s Wealth – From Ore to Usable Materials

Once extracted, raw ore is far from ready for human use. It must be separated, refined, and sometimes chemically transformed. This is the work of mineral processing, also known as ore dressing—the essential bridge between mining and manufacturing.

The goal: isolate valuable minerals from waste material (called gangue) and prepare them for final purification or industrial use.

Key Concepts

- Ore: A rock or sediment containing a desired mineral.

- Valuable Mineral: The material being targeted—like gold, copper, or lithium.

- Tailings: The waste left after valuable minerals are extracted.

- Concentrate: A higher-purity output of the valuable mineral, ready for final refining.

Stages of Mineral Processing

- Comminution (Crushing and Grinding)

Ore is mechanically broken into smaller pieces using jaw crushers, ball mills, or SAG mills. This increases surface area for further separation. - Screening and Classification

Particles are sorted by size. Larger fragments are recycled back for further crushing; smaller particles continue to separation steps. - Separation Techniques

These vary depending on the physical and chemical properties of the minerals involved:

- Gravity Separation: Uses density differences. Example: gold panning.

- Flotation: Bubbles attract hydrophobic minerals, lifting them to the surface.

- Magnetic Separation: Separates magnetic from non-magnetic particles.

- Electrostatic Separation: Uses charge differences.

- Leaching (Hydrometallurgy): Solvent dissolves minerals (e.g., cyanide for gold, acid for copper).

- Pyrometallurgy: High-temperature extraction (e.g., smelting iron or copper).

- Gravity Separation: Uses density differences. Example: gold panning.

- Dewatering and Drying

Removes water to prepare concentrates for transport and smelting.

Why It Matters

- Efficiency: Processing concentrates the valuable portion, making final purification more economical.

- Environmental Impact: Reduces the volume of material that must be transported or refined.

- Waste Management: Responsible processing reduces tailings and facilitates water recycling, energy savings, and cleaner effluents.

Innovations and Sustainable Practices

- Closed-loop water systems

- Tailings reprocessing

- Energy-efficient comminution

- Green chemistry alternatives for leaching

- AI and sensors for real-time process control

From crushing rocks to recovering micron-sized particles of platinum, mineral processing is a marvel of human engineering—and a focal point for improving sustainability.

5. Impacts of Mining – Environmental, Social, and Economic

Mining is never neutral. While it provides essential resources, it also brings profound consequences—many of which extend far beyond the boundaries of a mine. A truly Integrated Humanist approach requires acknowledging these trade-offs, working to mitigate harm, and ensuring that mining contributes to long-term human and ecological flourishing.

Environmental Impacts

- Habitat Destruction

Forests, wetlands, and fragile ecosystems are cleared for mine sites, causing biodiversity loss and irreversible landscape changes. - Water Pollution

Tailings and chemical runoff (such as cyanide, mercury, and acid mine drainage) can contaminate rivers, groundwater, and oceans. - Air Pollution

Dust, methane, and emissions from heavy machinery contribute to respiratory issues and greenhouse gases. - Soil Degradation

Topsoil removal and erosion leave land infertile and prone to desertification. - Climate Change

Fossil fuel extraction and the energy intensity of mineral processing are significant contributors to carbon emissions.

Social Impacts

- Displacement and Land Rights

Entire communities—often Indigenous or rural—are forced off ancestral lands with little or no compensation. - Health Risks

Workers and nearby populations face increased exposure to dust, toxic chemicals, and contaminated water. - Conflict and Corruption

In some regions, mining operations are linked to human rights abuses, funding of armed groups, and political instability. - Cultural Loss

Sacred sites and historical landscapes are often destroyed in the rush for resources.

Economic Impacts

- Job Creation and Infrastructure

Mining can bring employment, roads, schools, and hospitals—particularly in developing regions. - Boom-Bust Economies

Many mining towns flourish during extraction but collapse when resources run out. - Resource Dependence

Countries rich in minerals may suffer from the “resource curse”: corruption, inequality, and weak economic diversification. - Global Supply Chains

Mining forms the foundation of electronics, energy, and agriculture—but also enables consumerism that drives environmental overshoot.

Mining’s legacy is complex. It has built civilizations—and scarred landscapes. It has lifted people from poverty—and plunged others into exploitation. For Integrated Humanists, the imperative is to ensure mining serves humanity, not just markets; and sustains life, not just profit.

6. Toward Sustainable Mining – Technology, Policy, and Ethics

If mining is to be part of a livable future, it must evolve—radically and responsibly. Sustainability in mining isn’t just about reducing harm; it’s about rethinking how we define value, how we design systems, and how we distribute both risks and rewards. Integrated Humanism calls for a transformation guided by science, justice, and long-term stewardship.

Technological Innovations

- Automation and Robotics

Machines now handle some of the most dangerous tasks: autonomous trucks, tunnel-boring robots, and AI-guided drilling reduce injury and boost efficiency. - Real-Time Sensing and AI Optimization

Smart sensors detect ore composition and environmental conditions, enabling precision mining with minimal waste and energy. - Remote and Modular Mining Systems

Smaller, localized units reduce the need for massive site disruption, making mining feasible with lower ecological impact. - Green Processing Technologies

Innovations include waterless ore beneficiation, bacteria-based bioleaching, and non-toxic chemical solvents replacing cyanide and mercury. - Reclamation and Rewilding

Advanced land restoration, soil engineering, and ecological design help rehabilitate mined lands for farming, forests, or conservation.

Policy and Regulation

- Stronger Environmental Standards

Enforceable global limits on pollution, deforestation, and waste are vital for curbing long-term damage. - Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC)

Indigenous and local communities must have the right to say no—or negotiate fair terms—before mining begins. - Transparency and Anti-Corruption

Initiatives like the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) help fight illicit financial flows and strengthen civic oversight. - Circular Economy Incentives

Tax policies and subsidies should reward recycled materials, waste recovery, and innovation in material efficiency.

Ethical Frameworks and Human Values

- Environmental Justice

Addressing the disproportionate impact of mining on marginalized communities, especially in the Global South. - Intergenerational Equity

Ensuring that future generations inherit viable ecosystems, not toxic legacies and exhausted landscapes. - Holistic Impact Assessments

Mining projects must be evaluated not only for profit but also for effects on health, biodiversity, culture, and long-term wellbeing. - Education and Accountability

Mining companies, governments, and consumers must be informed—and held accountable—for their roles in the resource chain.

In short, sustainable mining demands more than better machines. It requires a new mindset—one that treats Earth not as a resource to be consumed, but as a partner in the human journey. Only through this shift can extraction be reconciled with ethics, ecology, and equity.

7. The Future of Mining – A Vision of Integrated Humanist Stewardship

What does a truly ethical and sustainable mining future look like? Not just cleaner machines or tighter regulations, but a complete reorientation of our relationship with the Earth. Integrated Humanist stewardship envisions a future in which resource extraction is aligned with science, democracy, ecological wisdom, and moral responsibility.

Principles for the Future

- Extract Only What Is Needed

A restrained approach that prioritizes recycling, material efficiency, and long-term planning over short-term profit or unchecked consumption. - Design for Disassembly and Reuse

Products should be built with their end in mind—modular, recyclable, and easily disassembled to reclaim materials. - Global Standards and Local Voices

International frameworks should ensure equity and justice, while local communities must retain the power to say yes, no, or change the terms. - Resource Sovereignty and Fair Trade

Nations and communities must control how their resources are used—reaping fair benefits while avoiding exploitation and dependency. - Earth Systems Science at the Core

Mining must be informed by the latest ecological, geological, and climate science, recognizing planetary boundaries and feedback loops.

Technologies to Watch

- Asteroid and Deep-Sea Mining (With Caution)

Emerging frontiers raise both promise and peril. These must be approached with global oversight and rigorous precaution. - Urban Mining and E-Waste Recovery

The “above-ground mine” of discarded electronics may soon rival traditional ore bodies in value—if we invest in recovery systems. - Artificial Intelligence and Circular Economy Platforms

Smart systems can track, optimize, and minimize resource use across entire supply chains. - Decentralized, Modular Mining

Smaller, local, and community-run mining systems may replace the mega-operations of today, reducing footprint and improving governance.

From Extraction to Stewardship

An Integrated Humanist future doesn’t reject mining. It transforms it—from an exploitative industry into a mindful system of stewardship. It replaces boom-bust greed with long-term wisdom, unregulated extraction with global cooperation, and ecological harm with ecological care.

In this future, mining is no longer a blind force of industrial hunger—but a conscious part of humanity’s evolutionary responsibility. A practice of working with the Earth, rather than just taking from it.

8. Conclusion – Responsible Resource Use in the Age of Intelligence

The ground beneath our feet holds riches that have built civilizations and sustained dreams—but also scars that tell stories of recklessness, violence, and waste. Mining is neither good nor evil. It is a tool. And like all tools, its value depends on how—and why—we use it.

In the Age of Intelligence, where global communication, environmental science, and ethical reasoning are more advanced than ever, we are called to transcend the blind extractionism of the past. We must move from a culture of consumption to one of stewardship. From short-term gains to long-term responsibility. From industrial conquest to Integrated Humanist care.

This means more than technological improvements. It means reimagining our systems of value—so that clean water is worth more than coal, and human dignity more than gold. It means designing policies and products that respect ecological limits and honor cultural heritage. And it means empowering citizens to hold industries and governments accountable, ensuring that mining serves life rather than undermines it.

The future of mining must be guided by science, shaped by ethics, and governed by inclusive dialogue. We must educate ourselves and each other—not only about how to extract and refine, but about when to stop, how to restore, and what truly matters.

This is the promise of Integrated Humanist stewardship: a world in which resource use serves not only industry, but humanity—and all life on Earth.

Bibliography

Bebbington, A., Abdulai, A.-G., Humphreys Bebbington, D., Hinfelaar, M. and Sanborn, C.A., 2018. Governing Extractive Industries: Politics, Histories, Ideas. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bridge, G., 2004. Contested terrain: mining and the environment. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 29(1), pp.205–259.

Gordon, R.B., Bertram, M. and Graedel, T.E., 2006. Metal stocks and sustainability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(5), pp.1209–1214.

Hilson, G., 2002. An overview of land use conflicts in mining communities. Land Use Policy, 19(1), pp.65–73.

International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM), 2022. ICMM 10 Principles: Mining with Principles. [online] Available at: https://www.icmm.com/en-gb/our-principles [Accessed 12 Jun. 2025].

Kinnaird, T.C., Bolle, S., Keenan, D. and Mount, R., 2021. Towards Responsible Mining: Building the ESG Credentials of the Mining Industry. Journal of Sustainable Mining, 20(2), pp.79–86.

Mudd, G.M., 2010. The environmental sustainability of mining in Australia: key mega-trends and looming constraints. Resources Policy, 35(2), pp.98–115.

Natural Resources Canada, 2023. Minerals and Mining in Canada. [online] Available at: https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/mining-materials [Accessed 11 Jun. 2025].

Rosenblum, P. and Maples, S., 2009. Contract Confidential: Ending Secret Deals in the Extractive Industries. Revenue Watch Institute.

Tost, M., Hitch, M., Gondran, N., et al., 2018. The state of environmental sustainability considerations in mining. Journal of Cleaner Production, 182, pp.969–977.

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), 2020. Mineral Resource Governance in the 21st Century: Gearing Extractive Industries Towards Sustainable Development. Nairobi: UNEP.

World Bank, 2019. The Growing Role of Minerals and Metals for a Low Carbon Future. [online] Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/extractiveindustries [Accessed 12 Jun. 2025].