Table of Contents:

- Introduction – The Age of the Screen

From Paper to Pixels: How screens became the lens through which we see the world. - A Short History of Screens and Human Attention

- The silent film and black-and-white television era

- Color TV and the golden age of broadcasting

- Video cassettes, cable, and the home entertainment revolution

- The digital age: DVDs, video games, digital clocks

- The internet explosion: desktop computing and early mobile devices

- Smartphones, tablets, and 24/7 access

- Streaming, binge-watching, and ambient screen use

- The silent film and black-and-white television era

- The Many Faces of the Screen

- Television

- Desktop computers

- Laptops

- Smartphones

- Tablets and eReaders

- Public and wearable screens: ATMs, watches, glasses, signage

- Television

- Health and the Human Body in the Screen Era

- Eye strain, blue light, and screen distance

- Circadian rhythm disruption and sleep problems

- Posture, movement, and physical health

- Children and developmental concerns

- Digital detox and screen hygiene

- Eye strain, blue light, and screen distance

- The Mind and Emotions Behind the Glass

- Dopamine and digital stimulation

- Screen addiction and attentional shifts

- Anxiety, depression, and social comparison

- The power of storytelling, art, and shared experience

- Screens as emotional regulators (comfort, escape, habit)

- Dopamine and digital stimulation

- Content is King: What Screens Are Showing Us

- From MTV to TikTok: entertainment and identity

- Video games: interactivity, learning, and immersion

- News and information: trust, overload, and manipulation

- Music and visual art in the digital world

- The paradox of connection: social media and alienation

- From MTV to TikTok: entertainment and identity

- Children, Screens, and Learning

- Screens in education and early development

- Parental guidance, screen limits, and digital literacy

- Gaming and attention span debates

- Emerging research on e-learning vs. traditional methods

- Screens in education and early development

- Screen Time and Society

- Work, life, and remote culture

- Screens and civic participation (or disengagement)

- Inequality of access and the digital divide

- Global screen culture and cultural homogenization

- AI, algorithmic curation, and our future vision

- Work, life, and remote culture

- Conclusion – Toward a Balanced Screen Life

What science, ethics, and human well-being tell us about how to manage screen time wisely in the 21st century.

Introduction – The Age of the Screen

From Paper to Pixels: How screens became the lens through which we see the world.

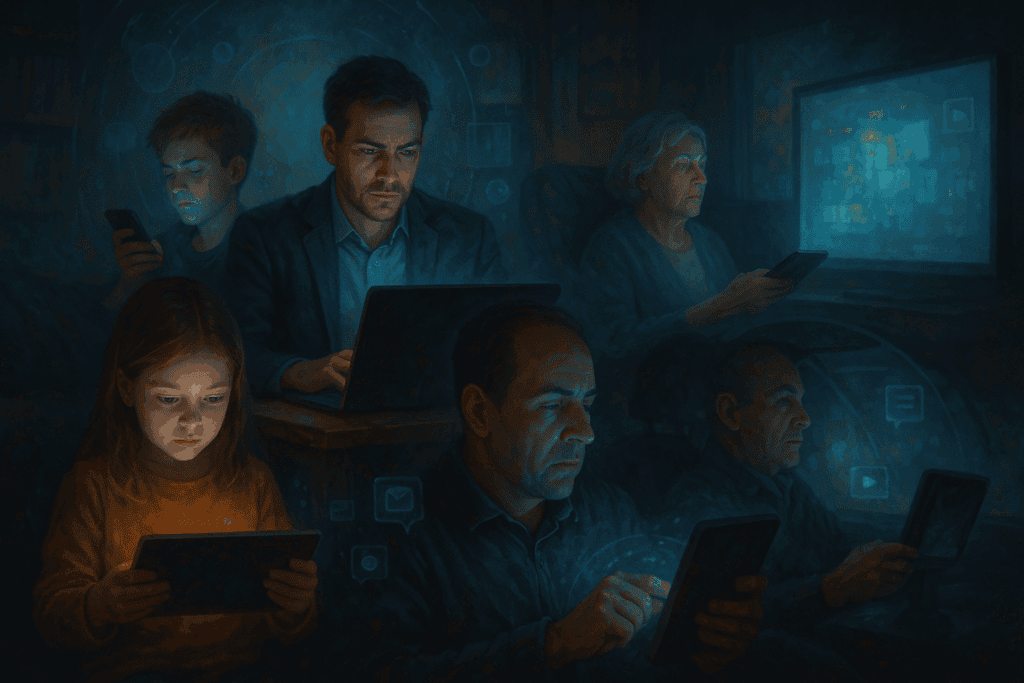

Once, the human gaze turned toward the horizon, the stars, a face, or a printed page. Now, it is most often drawn to a screen. From the grainy monochrome of early cinema to the glowing omnipresence of smartphones, the screen has evolved into humanity’s most dominant medium of interaction, entertainment, work, and even thought. Our modern lives are not just mediated by screens—they are shaped, structured, and sometimes even confined by them.

Screen time has become a defining metric of our era. It marks not only how we spend our hours but also how we process reality: the way we learn, communicate, relax, and express ourselves. Whether it’s a child tapping on a tablet, a teenager scrolling through TikTok, a professional toggling between Zoom and email, or an elder watching cable news, screens have transformed how we engage with time, space, and one another.

But this transformation is not without its consequences. Beneath the surface of convenience and connectivity lie questions of health, psychology, culture, and control. Are screens making us more informed or more distracted? More connected or more isolated? How do the messages and content they deliver affect our behavior, beliefs, and well-being?

This article explores the history, science, and impact of screen time in all its forms—television, computers, smartphones, tablets, and more. We’ll trace the evolution of screen technology, examine the physiological and mental effects of screen exposure, assess the content we consume, and consider the societal implications of living in a world where almost everything comes to us through a glowing rectangle.

This is the story of the screen—and what it means for a healthy, meaningful human life in the digital age.

2. A Short History of Screens and Human Attention

From flickering film to portable pixels: the evolution of our screen-filled world.

The story of screen time begins long before smartphones and streaming platforms. It begins in the theaters of the early 20th century, where the first moving images lit up the silver screen and transformed passive spectators into enthralled audiences. The cinema—black and white, silent, flickering—was our first portal into a new kind of mediated experience.

By the 1950s, television sets entered homes en masse, bringing family entertainment into the living room. These black-and-white boxes soon gave way to color TV, and later to cable networks offering round-the-clock programming. Attention, once shared communally in theaters, began to segment and specialize—Saturday morning cartoons for children, nightly news for adults, sitcoms and soap operas for everyone. The screen became a fixture of domestic life, its glow a steady presence.

The 1980s and 1990s saw a rapid expansion of screen-based media. VCRs let viewers control time itself, recording and replaying their favorite shows. Video game consoles like Atari and Nintendo introduced interactive screens, turning passive watching into active engagement. Arcades were packed with pixelated adventures, igniting a cultural shift toward gamified experiences.

As computing entered the home and workplace, desktop monitors became essential. The screen was no longer just for watching—it became a workspace. By the early 2000s, laptops and digital devices accelerated this transformation, enabling screen-based productivity and entertainment on the go. Then came the true game-changer: the smartphone. With the launch of the iPhone in 2007 and the rise of Android, the internet, once tethered to a wall, now fit in our pockets.

Tablets, smartwatches, and e-readers followed, each creating new forms of screen engagement. Streaming services replaced physical media. Notifications replaced waiting. Always-on became the norm.

And with this constant screen access came a new kind of attention economy. Time, focus, and even identity became shaped by what we saw, shared, and consumed on screens. Whether it was the passive viewership of TV or the immersive entanglement of social media, human attention became a commodity—and the screen became its marketplace.

Today, whether through a child’s eyes locked on a YouTube video or an adult toggling between apps and meetings, we live in an era of mediated experience. To understand modern life, we must understand the screen—not only its form, but its function, its content, and its consequences.

3. The Many Faces of the Screen

From the living room wall to the palm of your hand: the physical diversity of digital life.

Not all screens are created equal. While their luminous surfaces may appear similar, the devices that house them shape our behavior, posture, attention span, and emotional response in profoundly different ways. Each screen comes with its own rituals of use, its own relationship to space, time, and human purpose.

Television

The original household screen, television remains a communal medium. It encourages collective viewing, often in a fixed place and on a large display. Television’s influence peaked in the late 20th century, creating shared cultural moments—from moon landings to sitcom finales. Though partially eclipsed by personal devices, it still dominates live events, sports, and news consumption.

Desktop Computers

Designed for stationary work, desktops introduced the age of multitasking, windows, and web browsing. With mouse and keyboard interfaces, they allowed deep engagement with tasks and ushered in the information age. Despite being less mobile, desktops still dominate office spaces and professional environments requiring processing power, precision, or extended work time.

Laptops

The evolution of computing mobility. Laptops blurred the line between office and home, work and leisure. Their portability expanded screen use into coffee shops, classrooms, bedrooms, and flights. They became both tool and companion, enabling everything from spreadsheets to Netflix binges.

Smartphones

The most intimate screen—carried in pockets, touched hundreds of times per day. Smartphones are portals to communication, entertainment, news, productivity, and self-expression. But they are also interruptive, demanding attention with constant notifications and fostering habits of micro-engagement that fragment focus.

Tablets and eReaders

Larger than phones, more tactile than laptops, tablets offer a hybrid experience—good for reading, drawing, streaming, and education. eReaders like the Kindle introduced screen-based reading with minimal eye strain, while tablets became popular in classrooms and medical fields for their ease of interaction.

Public and Wearable Screens

Screens are now embedded into the environment: from airport kiosks and car dashboards to digital billboards and wearable tech like smartwatches and AR glasses. These ambient screens don’t always ask for full attention—they subtly alter how we navigate space, time, and decision-making.

Each of these screens influences not only what we see but how we see—and how we behave. Television encourages longer, more passive viewing. Smartphones favor short bursts of interaction and instant gratification. Laptops and desktops demand sustained attention and productivity. Tablets float somewhere in between.

Understanding screen time, then, is not simply a matter of measuring hours. It’s about recognizing how different screens structure our relationships—with information, with others, and with ourselves.

4. Health and the Human Body in the Screen Era

The physical costs of digital life—from tired eyes to disrupted sleep.

As screens have proliferated, so too have questions about their impact on human health. Though they promise convenience and connection, excessive or poorly managed screen time can take a toll on our bodies—especially on our eyes, posture, sleep cycles, and overall well-being. What was once a temporary strain from watching a movie has become a chronic condition for millions living in front of glowing rectangles.

Eyes and Vision: Strain, Distance, and Blue Light

One of the most common effects of prolonged screen use is digital eye strain, also known as computer vision syndrome. Symptoms include dry eyes, blurred vision, headaches, and difficulty focusing. Staring at a screen reduces the natural blink rate, leading to eye dryness and fatigue.

Compounding this is screen distance. Phones are often held too close, causing eye muscles to work harder than they would when reading printed material or looking at a distant object. Prolonged focus on close-up screens—especially in children—has been linked to a global rise in myopia (nearsightedness).

Blue light emitted by screens also interferes with the body’s natural production of melatonin, the hormone responsible for regulating sleep. Exposure to screens late at night can delay sleep onset, reduce sleep quality, and disrupt circadian rhythms, especially in children and teenagers whose brains are still developing.

Posture, Movement, and Musculoskeletal Health

The sedentary nature of screen-based work and entertainment has led to increased reports of “tech neck,” back pain, and carpal tunnel syndrome. Slouching over laptops, craning over smartphones, and long hours seated at desks all contribute to chronic musculoskeletal issues.

Children and teens may be especially vulnerable, as habits formed during development can shape their posture for life. Physical inactivity tied to excessive screen time also raises risks of obesity, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes.

Screen Time and Children’s Development

The effects of screen exposure on young children are a subject of ongoing study and concern. Excessive screen time, especially passive watching, may impair the development of attention span, language, and social interaction. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends limited and carefully curated screen time for children under 5, emphasizing face-to-face interaction and physical play instead.

Mental and Emotional Effects Linked to the Body

The physical experience of screen time is often entangled with emotional responses—racing hearts during an intense video game, restless legs during a Netflix binge, or shallow breathing from doomscrolling. These bodily cues are subtle but real, tying the digital world to our nervous system in powerful ways.

Digital Hygiene and Healthy Practices

Solutions exist, and they begin with awareness. Following the 20-20-20 rule (every 20 minutes, look at something 20 feet away for 20 seconds), setting screen curfews before bedtime, using blue light filters, maintaining ergonomic workstations, and integrating screen-free activities throughout the day can reduce harm.

The screen itself is not inherently dangerous—but unchecked, unbalanced use can quietly wear down the body. In this era of omnipresent technology, understanding how to live with screens—not under them—is essential for maintaining physical health and long-term vitality.

5. The Mind and Emotions Behind the Glass

Inside the screen: how digital life rewires thought, emotion, and identity.

While screens alter the posture of our bodies, they also reshape the posture of our minds. What we look at—and how we look at it—profoundly influences cognition, mood, emotional resilience, and mental health. In the screen age, the human brain is not simply a spectator. It is constantly adapting, rewiring itself to meet the demands and stimuli of the digital environment.

Stimulation, Dopamine, and the Pull of the Screen

Many digital experiences are engineered to trigger brief, pleasurable neurochemical rewards—primarily through dopamine. Likes, messages, achievements, and content scrolls offer intermittent reinforcement, similar to the mechanisms of gambling. This turns casual browsing into compulsive checking, especially on smartphones and social media platforms.

The result? A global rise in behaviors often described as “screen addiction”—not a formal diagnosis, but a real phenomenon characterized by anxiety when disconnected, compulsive checking, and difficulty focusing without stimulation.

Attention Fragmentation and the Loss of Deep Focus

Screens, especially those connected to the internet, fragment attention. Push notifications, multitasking tabs, algorithmic content feeds—these features reward rapid engagement and penalize sustained focus. Over time, this shifts the mind toward a state of hyper-reactivity and shallow cognition, undermining long-form thought, creativity, and introspection.

Mental Health and Emotional Well-Being

Mounting research links excessive screen use—especially social media—to higher rates of anxiety, depression, loneliness, and low self-esteem, particularly among adolescents. The curated lives and filtered faces of others can distort one’s self-image, leading to comparison, inadequacy, and digital social pressure.

At the same time, screens also serve as emotional crutches. In moments of stress, boredom, or sadness, many turn to screens for comfort or escape. This can lead to emotional suppression or avoidance, rather than resolution and growth.

Screens as Tools for Emotional Connection

Yet the picture is not entirely bleak. Screens have also enabled unprecedented emotional connectivity: video calls with distant loved ones, support groups, therapy apps, and creative outlets for self-expression. For many marginalized or isolated individuals, digital communities provide life-affirming spaces that may not exist in their physical surroundings.

The screen is both mirror and mask. It can reflect our feelings back to us with clarity—or distort them beyond recognition. It can open the door to understanding—or trap us in echo chambers of emotion and belief.

The Power of Narrative, Art, and Beauty

Importantly, screens also deliver stories, music, poetry, and art. A single film or documentary can stir empathy, change minds, and open hearts. A video game can foster agency and collaboration. A livestreamed performance can bring awe to a living room.

Whether harm or healing arises depends on how, why, and for what purpose we use screens—and whether we remain aware of their silent influence on our inner world.

In the end, the challenge is not to reject screens, but to reclaim sovereignty over how they affect the mind. To use them consciously. To look not just at the screen—but through it, and beyond it.

6. Content is King: What Screens Are Showing Us

The medium is powerful—but the message still matters.

Screens are vessels. What fills them—whether uplifting or destructive, enlightening or numbing—shapes our minds and cultures just as much as the devices themselves. While debates about screen time often focus on quantity, an equally urgent question is quality: What are we consuming? Who controls the message? And how does content shape us?

From MTV to TikTok: Entertainment and Identity

Music Television (MTV) in the 1980s revolutionized how young people related to image, identity, and sound. Fast-forward to today, and TikTok, YouTube Shorts, and Instagram Reels offer endless streams of hyper-curated entertainment and social trends. These platforms shape not just taste—but self-presentation, language, humor, and even moral behavior. Culture is now not only watched—it is performed through the screen, remixable and viral.

Video Games: Interactivity, Agency, and Escapism

Video games evolved from arcades and consoles to massive, online, immersive worlds. They offer not just entertainment but interaction, narrative, and mastery. Games can cultivate problem-solving, cooperation, and spatial reasoning—but also addiction, aggression (in some genres), and a detachment from physical reality. The key is balance and critical literacy: understanding both the benefits and pitfalls of digital play.

News and Information: Truth, Overload, and Manipulation

Screens have replaced newspapers and radios as the primary delivery mechanism for news. But with speed and access comes chaos. Fake news, clickbait, algorithmic bubbles, and deepfakes now compete with serious journalism for attention. The screen no longer just informs—it provokes, entertains, and often polarizes.

At the same time, responsible digital media and independent platforms have democratized information, giving voice to those previously unheard. The screen is both battlefield and town square.

Music and Visual Art in the Digital World

Streaming platforms have made music globally accessible, transforming how artists reach audiences. Visual artists now share their work on Instagram or NFTs, bypassing traditional gatekeepers. Screens have expanded access to art—but also commodified it, often rewarding quick consumption over depth and originality.

The Paradox of Connection: Social Media and Alienation

Social media promised connection—and delivered comparison, surveillance, distraction, and performative intimacy. Studies show that passive scrolling increases feelings of loneliness and envy, while meaningful digital interaction (messaging, video calls, collaborative projects) can deepen relationships.

Ultimately, the impact of screen content is not neutral. Every clip, tweet, video, or post conveys a worldview. Cumulative exposure shapes values, self-image, desires, and even perception of truth. To be literate in the screen age is to become a discerning consumer and creator of content—not only absorbing media, but evaluating its origin, intent, and effect.

In a world where content is infinite and attention is finite, what we choose to watch, play, follow, and believe becomes a moral and psychological act. The screen gives us power—but it also asks us who we are.

7. Children, Screens, and Learning

Growing up in the glow: screens and the developing mind.

For today’s children, the screen is not a novelty—it is a constant. From animated shows and educational games to online classrooms and social media, children are immersed in screen environments from a remarkably early age. Parents, educators, and scientists now face the complex task of understanding how this digital immersion affects cognitive, emotional, and social development.

Screens in Early Childhood Development

The earliest years of life are a critical period for sensory, linguistic, and social growth. During this time, real-world interaction—touch, eye contact, play, and conversation—is essential. Excessive screen use, especially passive viewing of fast-paced or overstimulating content, has been linked to delays in speech, reduced attention span, and behavioral challenges in young children.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends no screen time (other than video chatting) for children under 18 months, and limited, high-quality content for toddlers and preschoolers, ideally co-viewed with an adult. The screen itself isn’t the issue—it’s the loss of responsive, real-world engagement that matters most.

Education and E-Learning: Opportunities and Trade-offs

In older children, screens become learning tools. Educational apps, digital classrooms, and multimedia resources offer interactive, individualized, and often engaging ways to absorb information. During the COVID-19 pandemic, screens became essential to maintaining academic continuity. They allowed for remote instruction, digital collaboration, and access to resources beyond physical classrooms.

However, e-learning also revealed serious challenges: screen fatigue, limited social interaction, inequities in device access, and difficulty maintaining motivation without in-person guidance. A well-designed digital curriculum can be powerful—but it must be carefully integrated with real-world learning experiences, especially in subjects that rely on social cues or hands-on activity.

The Debate Around Gaming and Attention

Video games, often demonized, can actually enhance certain cognitive skills—especially spatial reasoning, memory, and problem-solving. Yet concerns persist about violent content, overstimulation, and time displacement from physical play or reading. The issue is not gaming itself but moderation, content type, and the presence (or absence) of parental guidance and emotional support.

Parental Guidance and Digital Literacy

The most effective approach is not total restriction but guided exposure. Children need help interpreting what they see—whether that’s distinguishing ads from content, understanding online risks, or learning to regulate their emotions in response to overstimulating media.

Teaching digital literacy—how to analyze, question, and contextualize screen content—should be a central aim of 21st-century parenting and education. It’s not just about limiting screen time; it’s about shaping screen time into a healthy, empowering experience.

The Future of Learning in a Digital World

As artificial intelligence and augmented reality enter classrooms, the future of education will be even more screen-integrated. This offers profound opportunities for personalization, access, and creativity—but also demands a new philosophy of child development: one that combines ancient wisdom about play, movement, and imagination with modern tools for growth.

The goal is not to raise children without screens, but to raise children with screens—wisely, intentionally, and with the whole child in mind.

8. Screen Time and Society

From individual habits to collective transformation: how screens shape civilization.

Screens have changed not only how we think and feel—but how we live together. They have transformed the fabric of society: how we work, relate, learn, consume, protest, vote, and dream. Their influence now extends far beyond the personal, into the deepest structures of culture, economy, and power.

Work, Life, and the Remote Revolution

For decades, screens were associated with leisure—TV, movies, games. Today, they are equally tools of labor. Emails, spreadsheets, video conferences, virtual desktops—screens now dominate the modern workplace. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated a profound shift: millions began working from home, blurring the boundary between personal and professional life.

This shift has advantages—flexibility, less commuting, expanded access to global opportunities. But it also raises issues of burnout, digital surveillance, and the erosion of boundaries. “Logging off” is no longer a given. The screen follows us from morning alarm to midnight scroll.

Civic Life and Political Engagement

Screens have become key battlegrounds of democracy. Social media platforms spread news, organize protests, amplify voices—and also sow misinformation, tribalism, and distrust. A tweet can spark a movement—or a riot. A livestream can expose injustice—or fabricate it.

The promise of digital democracy lies in accessibility: anyone with a screen can speak, organize, and participate. But the peril lies in manipulation—algorithms, bots, echo chambers, and attention-hacking strategies that distort the public sphere. Citizens must now learn not only how to vote—but how to think critically in a digital world saturated with noise and narrative.

Inequality and the Digital Divide

Not everyone experiences screens equally. Around the world, billions still lack reliable internet, modern devices, or digital literacy. This “digital divide” reinforces and deepens existing inequalities in education, health care, and economic opportunity.

Even within developed nations, disparities persist: low-income families may share one device among many children, while others grow up in smart homes and cloud-connected classrooms. As society digitizes, access to screens—and the skills to use them wisely—becomes a form of power.

Global Screen Culture and Cultural Homogenization

Screens carry not just pixels but values. Hollywood, TikTok trends, Netflix narratives, and global influencers often override local traditions, languages, and identities. A teenager in Kenya, Brazil, or Thailand may spend more time immersed in Western content than in their own cultural heritage.

This creates both risk and potential. It can dilute cultural diversity—or it can foster global solidarity. The screen can flatten the world—or weave it together more closely than ever before.

AI, Algorithms, and the Future of the Screen

Increasingly, what we see on screens is not chosen by us—but for us. Algorithms predict, recommend, and curate, often invisibly. Artificial intelligence is now creating content—articles, music, images, even faces. These technologies may enhance convenience and creativity, but they also raise critical ethical questions about manipulation, bias, and human agency.

Who controls the screen controls the story. And in an algorithm-driven world, we must ask: who writes the code?

Screens are no longer just tools or distractions. They are environments. They shape our norms, institutions, identities, and relationships. To shape a healthy society in the screen age, we must design systems and cultures that place truth, equity, empathy, and human dignity at the center of our digital lives.

Only then can screens serve society—rather than the other way around.

9. Conclusion – Toward a Balanced Screen Life

Living with screens, not under them.

We are the first generation in history to live the majority of our waking hours in front of glowing rectangles. From work to play, communication to contemplation, the screen has become an extension of the self—a second skin, a second mind. It is both window and mirror, amplifier and filter. But it is not, and never should be, a master.

This article has traced the arc of screen time across human history: from the black-and-white flicker of early film to the portable, personalized portals of today’s smartphones and tablets. We’ve seen how screens have changed the body, the brain, the culture, and the social order—both elevating and diminishing aspects of what it means to be human.

The truth is not that screens are evil or redemptive. They are tools. And like all tools, they magnify intent. They reflect the values of those who build them—and those who use them.

To live well in the screen age requires more than moderation. It demands conscious engagement. This means:

- Choosing quality over quantity in content consumption

- Designing screen spaces that nourish creativity, empathy, and learning

- Teaching children not just to use devices, but to question them

- Building cultural and political systems that defend truth and access

- Taking seriously the signals of the body, the emotions of the mind, and the ethics of attention

It also means remembering what came before the screen: the book, the face, the walk, the sky. It means making space for boredom, silence, reflection, and wonder.

The screen is not going away. But neither is the soul.

We stand at a turning point—not of technology, but of choice. Will we continue down the path of passive consumption, fragmentation, and addiction? Or will we reclaim the screen as a servant of humanity, not its master?

The answer lies not in the screen, but in the one looking through it.

And that, still, is us.