Table of Contents

- The Biology of Eating: How the Human Body Uses Food

The Science of Digestion, Energy, and Nutrient Processing - Diet and Mental Health

How What We Eat Affects How We Think and Feel - Food, Disease, and Longevity

Nutrition as Medicine - Diets Around the World

Diversity, Tradition, and Globalization - The Environmental Impact of What We Eat

Agriculture, Emissions, and the Climate Crisis - Ethical and Spiritual Dimensions of Diet

Compassion, Consciousness, and the Plate - The Politics and Economics of Diet

Big Food, Subsidies, and the Power to Choose - Future Diets and Technological Innovation

Feeding 10 Billion Humans Sustainably - The Integrated Humanist Diet

A Philosophy for Personal and Planetary Well-Being - Conclusion: Food as a Path to Wholeness

Eating for the Body, the Earth, and the Human Future

Introduction

Why What We Eat Matters — to Ourselves and the World

What we eat has never been just about calories and nutrients. Food is survival, yes—but it’s also memory, identity, medicine, celebration, and power. In every culture, the act of eating has carried meanings far beyond biology, shaping how we live, how we think, and how we treat one another. Today, in an era of climate instability, chronic disease, and economic disparity, our daily food choices have become moral and political acts—whether we acknowledge them or not.

The human diet stands at a crossroads. On one hand, we’ve never had more access to scientific knowledge about health and nutrition, nor more diversity and abundance in our food supply. On the other hand, we’re facing mounting global crises tied directly to what and how we eat: rising rates of obesity and malnutrition, the depletion of soil and freshwater, greenhouse gas emissions from industrial agriculture, and profound inequalities in access to wholesome food.

This article explores the human diet not just as a matter of personal health, but as a multidimensional system that touches the body, mind, society, and planet. We’ll look at how food shapes brain chemistry and mood, how traditional diets evolved and what we can learn from them, how agriculture and climate change are intertwined, and how technology and philosophy might shape the diets of the future.

Ultimately, we ask: What would it look like to eat not only for our own well-being, but for the well-being of the Earth and all who live upon it? Can we nourish ourselves without doing harm? Can we create a food culture based on truth, empathy, and sustainability?

In the pages that follow, we offer a science-based, Integrated Humanist view of eating—one that affirms our deep biological needs, celebrates our cultural wisdom, and rises to meet the challenges of a shared planetary future.

1. The Biology of Eating: How the Human Body Uses Food

The Science of Digestion, Energy, and Nutrient Processing

Every bite we take is a complex biochemical transaction. Food enters our bodies as substance—and becomes energy, structure, thought, and motion. This transformation relies on a finely tuned system of digestion, nutrient absorption, metabolic regulation, and cellular repair—shaped over millions of years of evolution.

At the most basic level, we eat to gain energy and building blocks. Energy is measured in calories, which our bodies convert into heat, movement, and biological activity. The raw materials for this come from three primary macronutrients: carbohydrates, fats, and proteins.

Carbohydrates are the body’s most immediate fuel source—especially for the brain. Simple sugars deliver rapid energy, while complex carbohydrates from whole grains, vegetables, and legumes offer slower, more sustained release. They also carry vital dietary fiber, which supports digestion and stabilizes blood sugar.

Fats serve many essential functions: they provide long-term energy storage, insulate our organs, and form part of every cell membrane. Certain fats—like omega-3 fatty acids from seeds, nuts, and fish—also support brain and heart health. However, industrial trans fats and excessive refined oils are linked to inflammation and chronic disease.

Proteins are broken down into amino acids, the body’s structural and functional toolkit. These amino acids build muscle, enzymes, immune cells, and even neurotransmitters. Without sufficient protein, the body cannot grow, repair, or maintain itself.

Alongside macronutrients, we require micronutrients—vitamins and minerals. Though they don’t supply calories, they enable countless biological processes:

- Iron helps transport oxygen in the blood.

- Vitamin D modulates immune response and calcium absorption.

- Zinc, magnesium, B-vitamins, and others are essential for nerve signaling, metabolism, and cellular repair.

And beneath it all, we depend on water—the foundation of life. It enables digestion, detoxification, temperature regulation, and mental clarity. Without adequate hydration, nothing works as it should.

Equally important is the gut microbiome—a teeming ecosystem of bacteria and microbes that live in our digestive tract. These microbes aid digestion, synthesize nutrients, reduce inflammation, and communicate directly with the brain through the gut-brain axis. An imbalanced microbiome has been linked to obesity, anxiety, depression, and autoimmune conditions.

Unfortunately, many modern diets—high in sugar, additives, and ultra-processed foods—disrupt this intricate biological symphony. But when we eat real, nutrient-dense, plant-forward foods in harmony with our body’s needs, we restore our natural equilibrium.

The human body is not merely a machine—it is an intelligent, responsive organism. What we eat becomes what we are. And when we eat wisely, the body knows how to thrive.

2. Diet and Mental Health

How What We Eat Affects How We Think and Feel

We often separate the mind from the body, but biology doesn’t. Our brains are physical organs—nourished, energized, and influenced by the food we eat every day. What we consume doesn’t just shape our waistline or our energy levels. It plays a powerful role in shaping our mood, mental clarity, memory, and even our resilience against anxiety and depression.

At the heart of this connection lies the gut-brain axis—a complex communication network linking the central nervous system with the enteric nervous system, which governs the digestive tract. This bidirectional feedback loop is mediated by neurotransmitters, immune signals, and the gut microbiome, the colony of trillions of bacteria that help digest our food and influence brain chemistry.

Many of the neurotransmitters that affect our mood—like serotonin, dopamine, and GABA—are either produced in the gut or regulated by microbial activity. In fact, about 90% of the body’s serotonin is synthesized in the digestive system. When we eat in ways that support a healthy microbiome—through fiber-rich, plant-based, minimally processed foods—we promote mental stability and emotional resilience.

On the flip side, diets high in sugar, refined grains, and ultra-processed foods have been strongly associated with increased rates of depression, anxiety, irritability, and cognitive decline. These foods tend to spike blood sugar levels, trigger systemic inflammation, and degrade the integrity of the gut lining—disrupting both physical and mental balance.

Emerging research in nutritional psychiatry supports a strong link between dietary patterns and mental health outcomes:

- Mediterranean diets, rich in olive oil, nuts, vegetables, legumes, and fish, are associated with reduced risk of depression.

- Fermented foods like yogurt, kimchi, and sauerkraut supply beneficial probiotics that support gut health and emotional regulation.

- Omega-3 fatty acids, especially from flaxseed, walnuts, and fish, are anti-inflammatory and crucial for brain function.

- Vitamin B12, folate, magnesium, and zinc are all essential for cognitive health and nervous system repair.

In addition, practices like intermittent fasting, ketogenic eating, and low-glycemic diets are being studied for their potential to enhance neuroplasticity, support mental clarity, and even reduce the risk of neurodegenerative diseases.

None of this means food alone can cure mental illness—but it can create the conditions for a more stable, resilient mind. Just as sleep, exercise, and social connection shape our inner world, so too does the food on our plate.

A healthy mind begins in a healthy gut. By feeding ourselves thoughtfully, we don’t just nourish the body—we cultivate the mental clarity, calm, and emotional strength we need to meet life with integrity and grace.

3. Food, Disease, and Longevity

Nutrition as Medicine

The human body is remarkably adaptive. It can survive for decades on an imperfect diet, compensating for deficiencies, metabolizing toxins, and repairing damage as best it can. But survival is not the same as health. Over time, poor nutrition quietly undermines the body’s systems, accelerating aging and increasing vulnerability to chronic disease.

The modern epidemic of preventable illness—obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, stroke, certain cancers, autoimmune disorders—is closely linked to what we eat. These conditions are not simply the result of genetics or bad luck. They are often the cumulative outcome of everyday choices made in a food system designed for convenience, profit, and hyper-palatability rather than nourishment.

Ultra-processed foods, laden with added sugars, seed oils, artificial additives, and refined flours, flood the body with empty calories while starving it of essential nutrients. These foods disrupt hormonal regulation, damage the gut microbiome, fuel systemic inflammation, and stress the cardiovascular system. Over time, they can trigger or worsen conditions like metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and chronic fatigue.

In contrast, whole-food, nutrient-dense diets—rich in vegetables, legumes, fruits, nuts, whole grains, healthy fats, and lean proteins—support the body’s natural ability to prevent, manage, and even reverse many diseases. Nutrition is not just a protective factor; it is therapeutic.

This is evident in research on dietary interventions:

- The Mediterranean diet reduces risk of heart disease and cognitive decline.

- Plant-based diets have shown potential to reverse plaque buildup in arteries and reduce the need for medication in diabetic patients.

- Anti-inflammatory diets can reduce pain and improve outcomes in autoimmune conditions like rheumatoid arthritis.

- Diets emphasizing fiber and polyphenols are associated with lower cancer risk and improved digestive health.

Perhaps the most compelling evidence comes from the so-called Blue Zones—regions of the world where people live significantly longer, healthier lives. In Okinawa, Japan; Ikaria, Greece; Sardinia, Italy; Nicoya, Costa Rica; and Loma Linda, California, centenarians consistently eat minimally processed, mostly plant-based diets. They consume moderate portions, eat slowly, and often prepare food communally. Longevity, it seems, is not a miracle but a lifestyle—grounded in the wisdom of balance.

Importantly, food is not just about preventing disease—it is about cultivating vitality. A nourishing diet enhances immune function, supports graceful aging, protects brain health, maintains muscle and bone density, and fosters the energy needed to engage fully with life.

In the 21st century, we must move beyond the reactive model of medicine and toward a culture of nutritional literacy. Diet is not a footnote to health—it is one of its most powerful determinants. To live well and long, we must return to food that feeds not only the appetite, but the body’s deep intelligence and the rhythms of life itself.

4. Diets Around the World

Diversity, Tradition, and Globalization

Human beings have always adapted their diets to the land around them. From the steppes of Central Asia to the rainforests of the Amazon, traditional food cultures emerged through a combination of necessity, creativity, and accumulated wisdom. These diets—shaped by geography, climate, seasonality, and ritual—reflect not only what was available, but what was meaningful.

The Mediterranean diet—with its emphasis on olive oil, fresh vegetables, legumes, seafood, and modest portions of wine—is often cited as a model of heart-healthy eating. In Japan, especially Okinawa, meals are traditionally centered around sweet potatoes, rice, tofu, seaweed, fish, and green tea, with small portions and mindful eating practices. In India, plant-based meals rich in lentils, spices, whole grains, and fermented foods have long been central, many based on Ayurvedic principles tailored to individual constitutions.

Other traditional diets are equally diverse:

- In Mexico, corn, beans, squash, and chili peppers form a “three sisters” agricultural and culinary foundation.

- In the Middle East, diets include hummus, olive oil, bulgur, dates, and herbs.

- West African cuisines feature yams, millet, okra, leafy greens, and spicy stews.

- Indigenous peoples across the Americas and Australasia often centered their diets on foraged plants, roots, nuts, wild fish, and game—foods rich in fiber and micronutrients.

These dietary traditions were typically seasonal, plant-forward, minimally processed, and eaten in community. They provided a diverse range of nutrients and promoted longevity, strength, and social cohesion.

But in the last century, globalization and industrialization have dramatically changed how people eat. The spread of processed foods, fast food chains, packaged snacks, and sugary beverages—marketed aggressively across the developing world—has led to a convergence toward what some researchers call the “Western diet”: high in fat, sugar, sodium, animal products, and synthetic additives, and low in fiber and micronutrients.

This shift has triggered a double burden in many countries: malnutrition and micronutrient deficiency coexisting with rising obesity and chronic illness. As food production becomes more centralized and corporate-controlled, local food systems, culinary traditions, and agricultural diversity are being eroded.

Yet there is hope in the growing global food sovereignty movement: communities reclaiming their traditional foodways, protecting local seeds and crops, and revitalizing indigenous knowledge. There’s also a rising interest in culinary anthropology, ethical gastronomy, and the idea of slow food—valuing not just what we eat, but how we grow, prepare, and share it.

In honoring the world’s dietary diversity, we rediscover something essential: food is not just a personal fuel source. It is a social, cultural, and ecological act. When we lose touch with our culinary roots, we lose part of what it means to be human. And when we reclaim them, we nourish not just our bodies, but our place in the living fabric of the Earth.

5. The Environmental Impact of What We Eat

Agriculture, Emissions, and the Climate Crisis

Every meal we eat leaves an ecological footprint. From the water used to grow crops to the fuel burned in transportation and refrigeration, the global food system is one of the largest drivers of environmental degradation—and one of the most overlooked levers for planetary change.

Modern industrial agriculture is incredibly productive, but also resource-intensive and ecologically disruptive. It consumes nearly 70% of global freshwater, occupies over a third of the Earth’s land surface, and contributes between 20–30% of greenhouse gas emissions—more than all the world’s planes, trains, and automobiles combined.

A significant portion of that impact comes from animal agriculture, particularly cattle and dairy production. Cows emit large amounts of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, while their feed crops require vast quantities of land, fertilizer, and water. Deforestation in the Amazon and other tropical regions is often driven by the expansion of soy plantations—not for tofu or edamame, but for livestock feed.

Meanwhile, monoculture farming—the large-scale planting of a single crop like corn, wheat, or soy—strips the soil of nutrients, encourages pesticide overuse, reduces biodiversity, and leaves ecosystems vulnerable to collapse. These systems often rely heavily on synthetic nitrogen fertilizers, which produce nitrous oxide (another powerful greenhouse gas) and contribute to oceanic “dead zones” through runoff.

The environmental cost of our food is further amplified by global supply chains and food waste. Packaging, refrigeration, processing, and transportation add emissions at every stage. And yet nearly one-third of all food produced globally is wasted, much of it in wealthy countries—squandering not just food, but all the energy, water, and labor it took to produce it.

There is, however, a growing movement to reimagine how we eat—for the sake of the Earth. Plant-based and flexitarian diets have been shown to significantly reduce carbon emissions, land use, and water consumption. Transitioning even a portion of the population away from heavy meat consumption could yield massive climate benefits.

So too could adopting regenerative agriculture practices: rotating crops, composting, avoiding synthetic chemicals, restoring soil health, and integrating animals into land stewardship systems that enhance carbon sequestration. Agroecology, permaculture, and indigenous farming traditions offer models of food production that align with ecological balance.

Our food choices are not just about nutrition—they are about ecological citizenship. Every bite carries consequences that ripple outward: across forests and rivers, through the atmosphere, into the climate and the lives of future generations.

To feed ourselves sustainably, we must begin to ask: Where did this food come from? How was it grown? Who or what paid the price? And most importantly: What kind of world do we want to nourish?

6. Ethical and Spiritual Dimensions of Diet

Compassion, Consciousness, and the Plate

Beyond biology, beyond culture, food is also an expression of ethics—a daily, intimate encounter with the question of how we ought to live. Eating is not a neutral act. It reflects our values, our awareness, and our relationship with other living beings. What we consume, and how it is produced, tells a story about how we see the world and our place within it.

For many people, this awareness leads to a moral reconsideration of animal consumption. Philosophical traditions such as ahimsa in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism advocate non-harm toward all sentient beings. The rise of vegetarianism and veganism, though often rooted in health concerns, is increasingly tied to concerns about animal suffering, factory farming, and environmental destruction.

In the world’s spiritual traditions, food often occupies a sacred space.

- In Buddhism, monks eat only what is offered, cultivating gratitude and non-attachment.

- In Christianity, fasting is a practice of purification and self-restraint; the Eucharist transforms food into divine symbol.

- Judaism and Islam observe dietary laws that elevate consciousness and ethical responsibility—what is kosher, what is halal, and why.

- In Indigenous traditions, hunting and gathering are often accompanied by prayers, rituals of respect, and reciprocal offerings to the natural world.

Across these traditions, a core insight emerges: to eat mindfully is to recognize interdependence—the reality that our life is sustained by countless others, both human and nonhuman.

In modern secular contexts, this principle is being revived through ethical eating movements:

- Fair trade ensures workers are paid justly.

- Organic and biodynamic farming avoids chemicals harmful to people and ecosystems.

- Local food systems reduce environmental impact and strengthen community resilience.

- Food justice advocates fight for equitable access to healthy, affordable food, particularly in marginalized communities.

Even for those without religious affiliation, there is something deeply spiritual about the act of eating—especially when it is done with presence. To cook for others is to serve. To share a meal is to participate in a moment of trust and unity. To savor food with gratitude is to remember that we are both humble and blessed.

At its highest, a conscious diet becomes a practice of compassion in action: compassion for animals, for farmers, for the Earth, for ourselves. It asks us to move beyond convenience, beyond craving, and into an ethic of care.

In this way, eating becomes not just an act of consumption, but an act of participation in the sacred web of life. And each meal becomes an opportunity to live according to the world we believe is possible.

7. The Politics and Economics of Diet

Big Food, Subsidies, and the Power to Choose

Food may seem like a personal choice—but in reality, what ends up on our plates is shaped by vast systems of power, profit, and policy. From agricultural subsidies to advertising strategies, the politics and economics of food deeply influence what we eat, how much it costs, and who can access it.

In many countries, especially the United States, government subsidies heavily favor the production of commodity crops like corn, soy, wheat, and rice. These crops are used to manufacture cheap, calorie-dense processed foods—sugary snacks, fast food, and industrial animal feed—while fruits, vegetables, and sustainable farming practices receive comparatively little support. The result is a marketplace where the least healthy foods are often the most affordable and widely available.

This economic architecture is no accident. It has been built by decades of lobbying from the agribusiness industry, major food corporations, and industrial meat producers—collectively known as “Big Food.” These powerful entities influence dietary guidelines, market research, school lunch programs, and even scientific research. Their marketing budgets far outstrip those of public health organizations, targeting children and low-income communities with irresistible campaigns for foods high in sugar, salt, and fat.

Meanwhile, small-scale farmers, especially those growing diverse, organic, or culturally specific crops, struggle to compete. The consolidation of food production into fewer and fewer corporate hands has reduced biodiversity, displaced local economies, and widened the gap between consumers and the sources of their food.

Access is also a matter of equity. Millions of people around the world live in food deserts—urban or rural areas without reliable access to fresh, healthy, and affordable food. Others live in food swamps, inundated with convenience stores and fast-food outlets but lacking nutritious options. These disparities are often racialized and tied to broader systems of poverty and structural discrimination.

And yet, choice is not entirely an illusion. Around the world, communities are organizing to reclaim power over their food systems:

- Community-supported agriculture (CSA) links eaters directly to local farmers.

- Food co-ops and urban gardens restore agency and self-reliance.

- Public policy advocates fight for better labeling laws, limits on junk food marketing, and fair wages for food workers.

- Movements for universal basic nutrition seek to treat food not as a commodity, but as a human right.

The economic and political dimensions of diet reveal a hard truth: not all diets are created equal in access, quality, or consequence. To create a world where everyone can eat well, we must challenge the systems that profit from poor health and environmental damage—and design new ones grounded in justice, transparency, and long-term thinking.

In the end, the food system is not just an industry—it is a mirror. And what it reflects is the kind of society we are willing to accept.

8. Future Diets and Technological Innovation

Feeding 10 Billion Humans Sustainably

The 21st century faces a challenge no previous era has encountered: how to feed a projected 10 billion people by the year 2100, within the limits of a planet already straining under the weight of climate change, soil depletion, and collapsing biodiversity.

Meeting this challenge requires more than tweaking current systems. It demands a reimagining of what food is, how it’s made, and how it serves both human and planetary health. Fortunately, technology and science are already offering bold—and sometimes surprising—solutions.

One of the most talked-about innovations is lab-grown meat (also known as cultured or cultivated meat). Produced by growing animal cells in controlled environments without raising or slaughtering animals, this technology could dramatically reduce land use, water consumption, and methane emissions while addressing ethical concerns. Though still expensive and emerging, lab-grown meat is progressing rapidly, with pilot products already approved for sale in some countries.

Other protein alternatives include insect-based foods, such as cricket flour or mealworm protein bars, which are highly efficient to produce and rich in nutrients. In many cultures, entomophagy is traditional and sustainable. The barrier is not nutritional—it’s psychological.

Meanwhile, vertical farming and hydroponic systems are transforming agriculture by growing food in stacked layers indoors, using LED lights and recirculated water. These technologies drastically reduce the need for arable land and pesticides, and can bring food production closer to urban populations, reducing transport emissions.

Precision fermentation—the use of microbes to produce proteins and fats once only found in animals—is another frontier. It’s already being used to create dairy-free milk proteins, egg substitutes, and even realistic cheeses, without a single cow or chicken involved.

Technology also plays a role in personalized nutrition. DNA analysis, microbiome testing, and metabolic tracking are enabling individuals to tailor their diets to their own biology. Smart apps, AI-driven meal planners, and wearable nutrient monitors may one day guide us toward optimal eating in real time.

Still, innovation alone is not enough. Without ethical frameworks and democratic oversight, high-tech solutions can become tools of exploitation—concentrated in the hands of a few, inaccessible to the many, or driven by profit over justice. A sustainable future requires that innovation be aligned with the principles of equity, transparency, and planetary stewardship.

In the coming decades, we will likely see a hybrid landscape: high-tech urban food labs coexisting with regenerative rural farms; synthetic proteins alongside ancient grains; data-driven diet plans paired with traditional cooking practices. The key will be integration—blending modern ingenuity with timeless wisdom.

If we rise to the occasion, the future of food could be one of abundance, justice, and resilience. Not just survival—but a new harmony between humanity and the Earth.

9. The Integrated Humanist Diet

A Philosophy for Personal and Planetary Well-Being

In an age of ecological crisis, chronic illness, social division, and digital distraction, the question of what to eat can feel overwhelming. Fads rise and fall. Guidelines shift. Algorithms compete for our attention. Yet beneath all the noise, a deeper question endures: How can we eat in a way that honors both our own humanity and the interconnected life of the Earth?

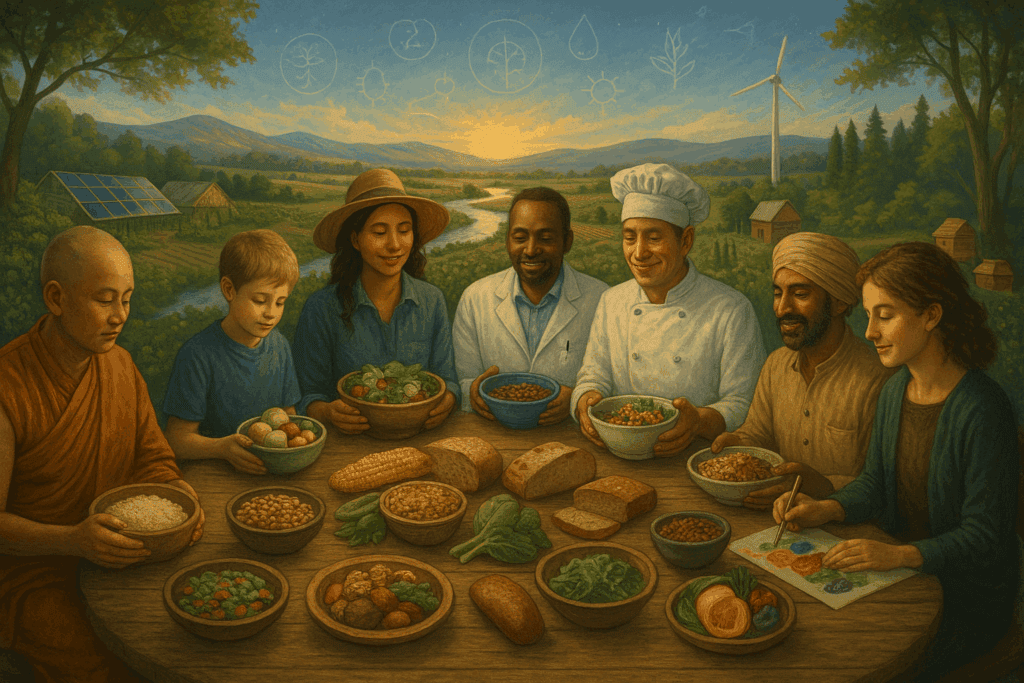

The Integrated Humanist Diet is not a rigid plan or prescriptive list—it is a philosophy. It recognizes that food is more than fuel. It is culture, ethics, ecology, science, memory, and meaning. It affirms that eating should nourish the whole person—mind, body, and conscience—while respecting the well-being of other people, other species, and future generations.

Rooted in science, informed by reason, guided by compassion, and elevated by shared human values, the Integrated Humanist approach to food emphasizes:

1. Health and Evidence-Based Nutrition

Eat a wide variety of whole, minimally processed foods—rich in fiber, color, and nutrients. Avoid excess sugar, synthetic additives, and ultraprocessed meals. Trust science, but don’t idolize industry.

2. Mindful Eating and Gratitude

Eat slowly. Be present. Listen to the body’s signals. Express thanks for what was grown, harvested, and prepared—for the unseen labor and natural cycles that make every meal possible.

3. Justice and Accessibility

Support food systems that are fair, democratic, and inclusive. Advocate for policies that ensure everyone—regardless of wealth or geography—has access to clean, nourishing food.

4. Ecological Integrity

Choose foods with low environmental impact. Favor plants. Reduce waste. Consider the water, soil, and energy behind each product. Eat not just for taste or tradition, but for the world you want to protect.

5. Cultural Wisdom and Culinary Diversity

Honor ancestral diets, local ingredients, and regional cooking practices. Resist monoculture and standardization. Let food be a celebration of pluralism and story.

6. Empathy and Ethical Awareness

Consider the lives of animals. Respect sentience. If you eat meat or animal products, do so with restraint and reverence—preferably from sources committed to humane and regenerative practices.

7. Community and Connection

Eat together. Cook with others. Share meals across generational and cultural lines. Food is a bridge—between strangers, between past and future, between self and planet.

At its heart, the Integrated Humanist Diet is not about restriction. It is about liberation—freeing ourselves from compulsive consumption, disconnection, and disinformation. It is a return to balance, dignity, and thoughtful pleasure.

In this vision, food becomes a daily ritual of alignment: with health, with knowledge, with compassion, with the Earth.

Conclusion: Food as a Path to Wholeness

Eating for the Body, the Earth, and the Human Future

In a world fragmented by crises—health, climate, inequality, and meaning—our relationship with food offers both a mirror and a compass. It reveals our habits, our assumptions, and our entanglement with systems we often do not see. But it also shows us a way forward: a daily, grounded opportunity to live with greater integrity, intelligence, and care.

Food is one of the few things that touches every human life, every day. It connects us across cultures and centuries. It links soil to cell, farmer to philosopher, climate to kitchen. And because it is so universal, food has the power to transform not just bodies—but societies.

We cannot solve the world’s problems through diet alone. But we can use diet as a starting point—for awareness, for solidarity, for healing. The simple act of choosing what to eat becomes a chance to vote for health, for justice, for compassion, and for the regeneration of our ecosystems.

This is the path of the Integrated Humanist, who does not eat blindly or selfishly, but consciously—honoring both science and spirit, both data and dignity.

To eat well is not to follow a trend. It is to remember who we are, where we come from, and what kind of world we want to leave behind.

Let us eat not just to survive, but to affirm life.

Let us nourish not just ourselves, but each other.

Let us grow a food culture worthy of the human future.