Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Search for a Moral Compass

- Foundational Concepts: Defining the Terrain of Moral Inquiry

- The Historical Evolution of Moral Systems

- Morality in the Modern World: Rights, Responsibilities, and Integrated Humanism

- Religion and Morality: Faith, Ethics, and Critical Thinking

- Moral Architecture: Freemasonry and the Science of the Good

- On Character: Insight, Emotion, and the Shaping of the Moral Self

- Game Theory and the Structure of Moral Choice

- Applied Ethics: Science, Community, and the Moral Test of Action

- The Aesthetic and Spiritual Dimensions of the Moral Life

- Conclusion: Toward a Science of Morality

Introduction: The Search for a Moral Compass

In a world of constant change and deep division, many of us find ourselves asking a timeless question: What is the right thing to do? We ask it in quiet moments of reflection, in the face of hard choices, and in response to suffering—our own or others’. We ask it not only as individuals, but as communities, as nations, and as a species. The answers matter.

And yet, too often, we are told that morality is relative, unknowable, or rooted only in faith. But what if there is another way? What if morality could be approached like any other aspect of human life—with curiosity, care, and clarity?

This essay is an invitation to rediscover morality not as a command from above or a whim of culture, but as a living science: one that evolves, adapts, and integrates knowledge from across the human experience. It begins with biology and philosophy, draws from ancient wisdom and modern evidence, and looks toward a future where ethics is not imposed but embodied—lived with honesty, empathy, and shared understanding.

We explore morality through the eyes of reason and the heart of compassion. We trace its path through religion and ritual, governance and game theory, aesthetics and the mind. We look at how people shape character, build community, make difficult choices, and live meaningful lives.

Above all, this is a comforting reminder:

You are not alone in your longing for a better world. The desire to do good—to live well and help others live well—is deeply human. It is not perfect. It is not easy. But it is possible. And it begins with understanding.

Whether you are a scientist or a seeker, a skeptic or a spiritual soul, this journey belongs to you. Let us walk together in pursuit of a morality that is wise, kind, and true.

Foundational Concepts: Defining the Terrain of Moral Inquiry

Before we begin exploring how morality functions and evolves, we must first define the key terms that shape the landscape of moral thought. These definitions provide clarity and consistency in a subject often clouded by cultural differences, philosophical disagreements, and emotional investments.

1. Worldview

A worldview is the overarching lens through which an individual or community interprets the nature of reality. It includes assumptions about existence, human purpose, knowledge, truth, values, and meaning. A worldview shapes not only how people perceive facts but also how they interpret right and wrong, justice and injustice, and the role of humanity in the universe.

2. Morality

Morality refers to a system of principles and judgments based on concepts of right and wrong. These principles guide human behavior, often aiming to minimize harm, promote well-being, uphold justice, and foster cooperation. Moral rules can be internally held or externally imposed, but they imply some form of accountability or obligation.

3. Ethics

Ethics is the philosophical study of morality. While morality often describes the actual codes people follow, ethics seeks to question, critique, and refine those codes. The term originates from the Greek word ethos, meaning “character” or “custom.” The choices we make using ethical reasoning ultimately shape our personal character and influence our shared cultural norms.

The root of the word “ethics” is ethos, signifying ‘character’ or, in the plural, ‘customs.’ The decisions we make with ethical reasoning define our integrity and underpin the moral customs of a society.

4. Moral Philosophy

Moral philosophy is the branch of philosophy concerned with evaluating human conduct through systems of value and duty. It investigates the nature of right and wrong, the justification of moral beliefs, and the criteria for moral judgment.

5. Situational Ethics

Situational ethics holds that the morality of an action depends on the context rather than adherence to absolute rules. It was popularized by Joseph Fletcher in the 20th century and emphasizes love, compassion, and context as moral guides.

6. Secular Morality

Secular morality refers to ethical systems not derived from religious authority. Instead, they are based on reason, empathy, human experience, and shared societal values. Secular moral systems may align with religious principles but are not dependent on them for justification.

7. Secular Humanism

Secular humanism is a worldview and ethical framework that emphasizes reason, scientific inquiry, individual dignity, and cooperative ethics without recourse to the supernatural. It upholds that human beings are capable of morality and self-fulfillment within the bounds of a purely naturalistic worldview.

A Secular Scientific Democratic Humanist Manifesto

The Foundations of Morality

Across history and across cultures, philosophers and scientists have proposed three primary foundations for morality:

1. Biological Foundations

From an evolutionary standpoint, human beings evolved moral instincts—such as empathy, cooperation, and fairness—as survival mechanisms. These behaviors enhanced group cohesion and improved reproductive success. Neuroscience also reveals that parts of the brain (e.g., prefrontal cortex, amygdala) are involved in moral reasoning, suggesting a biological substrate for ethical decision-making.

2. Philosophical Foundations

Philosophers have long debated the rational and normative basis for morality. Through ethical systems such as utilitarianism, deontology, virtue ethics, and care ethics, they explore how humans ought to behave, beyond biological impulse or social conditioning.

3. Societal Foundations

Moral norms are also shaped by culture, tradition, and social consensus. Every society develops rules—both formal (laws) and informal (customs)—that guide behavior, maintain order, and reflect shared ideals. These norms evolve over time, shaped by historical context, religious belief, political structures, and technological changes.

4. Conscience and Its Disorders

The conscience is the inner sense or voice that guides individuals to judge their actions as right or wrong. While most people possess a functional conscience, various psychological disorders can distort or suppress moral reasoning:

- Moral insanity (historical term) referred to individuals with normal intellectual faculties but impaired moral judgment.

- Personality disorders such as psychopathy or narcissistic personality disorder may involve reduced empathy, impulsivity, and disregard for others—traits that undermine ethical behavior.

These cases challenge the assumption that everyone shares the same moral compass and highlight the importance of mental health in ethical agency.

5. Meaning, Virtue, and the Drive to Transcend the Self

Beyond rules and norms, moral living often involves striving for something greater than oneself. Meaning in life emerges when individuals:

- Act with courage, facing their fears with integrity.

- Engage in productive and prosocial action, benefiting both self and others.

- Participate in collective purpose, contributing to communities, nations, or the future of humanity itself.

This pursuit of meaning lies at the heart of many moral and philosophical traditions—from the Confucian junzi (noble person) to the Greek idea of eudaimonia (human flourishing), to modern existential humanism.

The Historical Evolution of Moral Systems

To understand morality as a human phenomenon, we must trace its development from ancient legal-religious codes to the philosophical traditions of Greece, India, and China, and onward to modern secular theories of justice, rights, and dignity. The historical trajectory reveals how moral thought matured alongside human civilization, law, and governance.

1. From Myth to Morality: The Heroic Transformation

One of the earliest recorded moral narratives is found in The Epic of Gilgamesh, a Mesopotamian tale dating to at least 2100 BCE. Gilgamesh begins as a tyrannical figure, acting on selfish impulse, but through friendship, loss, and confrontation with mortality, he is transformed. He learns restraint, compassion, and responsibility—a transition from the raw “natural man” to the civil man guided by wisdom. This theme—the moralizing of the self—is repeated in countless cultural myths and religious stories.

2. Ancient Legal-Moral Codes

Many ancient civilizations encoded moral duties in legal-religious forms:

- Mesopotamia: The Code of Hammurabi (~1750 BCE) was among the earliest formal legal codes. It emphasized justice, retribution, and social order under divine authority.

- Judaism: The Torah presents a moral covenant between God and humanity, laying out commandments (mitzvot) as both ethical and ritual obligations.

- India: The Dharmaśāstras and Buddhist precepts outline duties, nonviolence, compassion, and karma, linking moral behavior to cosmic justice.

- China: Confucianism emphasized ethical self-cultivation, filial piety, ritual propriety (li), and governance by virtue rather than punishment.

- Egypt: Ma’at represented cosmic and ethical order; morality was obedience to this harmony.

- Greece: The Greeks pioneered the use of reason in ethics. The concept of natural law (especially in Stoicism) suggested that moral truths could be discovered through reflection on human nature and reason.

These early traditions demonstrate a blend of divine law, civic duty, and virtue cultivation as foundations for moral systems.

3. The Golden Rule and the Universality of Reciprocity

Nearly every ancient tradition articulated a version of the Golden Rule: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” This simple principle, grounded in empathy and fairness, may be humanity’s earliest ethical algorithm.

Its rational foundation is clear: No mentally healthy person desires to be harmed, enslaved, raped, or tortured. Thus, when individuals such as Christopher Columbus committed acts of violence, slavery, and genocide, these cannot be excused as morally relative—because the victims, like any of us, did not wish such suffering upon themselves. This reveals a universal moral metric: if a deed causes extreme suffering and violates reciprocal dignity, it is immoral, regardless of context.

4. Nobility, Honor, and Moral Identity

In ancient Greek philosophy, a distinction arose between the noble (kalon) and the base (aischron). To be base was to act from cowardice, indulgence, or selfishness. To be noble meant to pursue excellence (aretē), justice, and honor beyond self-interest.

The moral ideal of the noble person eventually evolved into civic archetypes:

- The Confucian gentleman or junzi, who governs himself before he governs others.

- The Greek philosopher-statesman, who rules by reason and cultivates the soul.

- The Roman citizen, loyal to duty and honor.

- The Enlightenment gentleman, educated, rational, and committed to liberty and justice.

Honor, especially in Western tradition, was a moral status tied to truthfulness, integrity, duty, and sacrifice. In the Declaration of Independence, the signers pledged “our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor”—evoking a moral claim more binding than law or profit.

Honor, as classically understood, is the lived expression of internal virtue recognized by the community. It implies integrity in word and deed, a commitment to justice, and a willingness to endure hardship for principle.

5. Socratic Ethics and the Birth of Moral Philosophy

With Socrates, moral inquiry took a dramatic shift from external authority to internal reasoning. Through the Socratic method—questioning assumed truths—Socrates argued that no one does wrong willingly; all wrongdoing stems from ignorance. Morality, he claimed, was the pursuit of self-knowledge and virtue.

Plato extended this with his theory of the soul’s harmony and the Forms (perfect ideals, including Justice and Goodness). Aristotle, in the Nicomachean Ethics, grounded morality in virtue ethics, suggesting that human flourishing (eudaimonia) results from cultivating habits of courage, temperance, and reason.

These thinkers laid the groundwork for normative ethics, influencing Christianity, Islamic philosophy, and the Enlightenment.

6. The Leviathan and the Social Contract

In the wake of brutal wars and collapsing order, Thomas Hobbes proposed a secular moral theory in Leviathan (1651). He argued that in a natural state, life is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” To escape this chaos, people form a social contract, ceding certain freedoms in exchange for security and civil peace.

Later thinkers, such as John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Immanuel Kant, refined this idea:

- Locke emphasized natural rights to life, liberty, and property.

- Rousseau envisioned a general will expressing the moral unity of a community.

- Kant formulated the categorical imperative, insisting that we act only according to principles that could be universal laws.

These Enlightenment theories asserted that morality is rational, secular, and universalizable—and they formed the basis of modern democratic ideals and human rights.

Morality in the Modern World: Rights, Responsibilities, and Integrated Humanism

In the wake of global upheavals—colonialism, revolutions, world wars, and economic transformations—moral philosophy has become increasingly institutionalized in law, policy, and public discourse. The modern era has witnessed the convergence of philosophical ethics, legal codification, and international cooperation. These developments have given rise to a global moral framework grounded in secular principles, universal rights, and shared responsibility.

1. Human Rights and Moral Responsibility

The concept of human rights represents one of the most significant moral achievements of the modern world. Rights such as liberty, equality, freedom from torture, and access to education are now enshrined as universal values that transcend cultural or national differences. Equally important is the recognition that rights are accompanied by responsibilities: the duty to uphold the rights of others, to protect the vulnerable, and to participate constructively in society.

The Evolution of Rights:

- Magna Carta (1215): The English barons forced King John to accept limitations on royal authority, laying a foundation for legal checks and individual liberties.

- Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789): A product of the French Revolution, this declaration emphasized liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression.

- The Age of Reason: Thinkers such as Rousseau, Locke, and Paine advanced the idea that governments derive legitimacy from the consent of the governed, and that individuals possess inalienable rights.

- The American Bill of Rights (1791): Codified core civil liberties such as freedom of speech, religion, assembly, and due process.

These foundational texts informed the later development of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), adopted by the United Nations in 1948. Drafted after the devastation of World War II, the UDHR was a landmark in global moral consensus. It set forth thirty articles affirming the dignity, equality, and freedoms to which all people are entitled.

The UDHR has since inspired:

- The European Convention on Human Rights

- The International Criminal Court

- The World Bank’s development goals

- Numerous global agreements in health, labor, and environmental law

Today, the principles embedded in these charters serve as a global moral compass, albeit imperfectly enforced.

2. Morality and Government: From Sovereignty to Solidarity

The relationship between morality and government is central to any vision of human flourishing. At its best, government embodies shared ethical commitments—justice, equity, security, education, and the common good. Secular democratic institutions are designed to translate ethical ideals into public policy, while safeguarding freedom and pluralism.

The rise of Scientific Humanist Democracy—or Integrated Humanism—proposes a governance model that fuses:

- Evidence-based policy and reason (science)

- Universal dignity and mutual care (humanism)

- Inclusive citizenship beyond religious or national boundaries (secularism and cosmopolitanism)

In this view, governments do not derive authority from divine mandate, but from their ability to foster well-being and protect the rights of all citizens through rational governance and moral accountability.

3. Honor, Duty, and the Moral Citizen

In modern ethical discourse, honor has evolved beyond aristocratic codes to signify moral integrity, public trust, and self-respect. Duty, meanwhile, refers not only to national service but to civic responsibility, environmental stewardship, and global solidarity.

To be an ethical citizen in the 21st century means:

- Acting with integrity even when inconvenient

- Serving one’s community and future generations

- Participating in democratic processes with informed judgment

- Holding leaders and institutions morally accountable

These values reframe patriotism not as blind loyalty to a state, but as commitment to a just and thriving society.

4. Cosmopolitanism, Globalism, and the New Moral Order

Global interconnectedness—economic, digital, cultural—has prompted new debates over identity, loyalty, and morality.

Key concepts:

- Cosmopolitanism: The belief that all humans are part of a single moral community. It originated with Diogenes (“I am a citizen of the world”) and was further developed by Stoics, Enlightenment thinkers like Kant (who proposed a cosmopolitan law for perpetual peace), and modern philosophers of global justice.

- Globalism: Often a neutral term referring to the global scope of interconnected systems; however, it has been co-opted by various ideologies:

- Market globalism promotes deregulated capitalism and transnational markets.

- Jihad globalism refers to transnational religious militarism.

- Liberal institutionalism (e.g., UN, EU, G20, OECD) seeks cooperative global governance.

- Market globalism promotes deregulated capitalism and transnational markets.

- Nationalism vs. Internationalism:

- Nationalism promotes sovereign interests and cultural identity, sometimes at the cost of others.

- Internationalism emphasizes collaboration and common humanity across borders.

- Nationalism promotes sovereign interests and cultural identity, sometimes at the cost of others.

Challenges:

- Neoliberalism, by reducing all values to market logic, has sometimes weakened social cohesion and ethical priorities.

- Populist nationalism has reasserted tribal boundaries, often weaponizing “patriotism” against cosmopolitan ideals.

- Conspiracy theories portray global cooperation as elitist domination, undermining trust in shared institutions.

A Scientific Humanist perspective upholds cosmopolitanism and international cooperation, while demanding democratic transparency and equity. It aims to transcend narrow nationalism without surrendering cultural diversity or civic accountability.

5. Integrated Humanism: A Moral Framework for the Future

As humanity faces complex global challenges—climate change, AI ethics, migration, inequality, authoritarianism—a new moral philosophy is emerging: Integrated Humanism.

This framework synthesizes:

- Scientific understanding: grounding values in what promotes well-being, life, and sustainability.

- Humanist ethics: centering empathy, rights, and the flourishing of conscious beings.

- Democratic structure: ensuring participation, accountability, and justice.

- Global vision: affirming that moral obligation transcends race, religion, and nationality.

Integrated Humanism does not call for a world government, but for a shared moral consciousness—an Earth-wide civic ethic grounded in evidence, compassion, and courage.

Religion and Morality: Faith, Ethics, and Critical Thinking

1. Religion as a Source of Moral Systems

For much of human history, religion has served as the primary framework for moral education, regulation, and ritual discipline. Sacred texts, divine commandments, and the authority of religious leaders have offered communities moral structure and meaning. Yet, the relationship between religious belief and ethical behavior is complex, and it evolves across time, tradition, and interpretation.

Religious ethics may include:

- Categorical rules (e.g. “Thou shalt not kill”)

- Aspirational ideals (e.g. love, compassion, nonviolence)

- Prescriptive rituals that express or reinforce moral identity

- A belief in divine justice or karmic retribution as moral enforcement

At their best, religious traditions inspire virtue, altruism, community service, and reverence for life. However, when tied to dogma or authoritarian structures, religion can inhibit moral autonomy, suppress inquiry, and justify violence or exclusion.

2. Faith and Critical Thinking

The relationship between religion and critical thinking varies widely. Some religious individuals integrate rigorous reasoning with spiritual inquiry, while others hold beliefs immune to examination.

Critical thinking is defined as the ability to evaluate claims, evidence, and arguments through rational reflection. Its goals include truth, clarity, coherence, and usefulness. Yet certain religious modes of thought may discourage or even oppose critical scrutiny—particularly when faith is framed as belief without evidence.

Research Findings:

- Studies suggest that high religiosity is often associated with a preference for intuitive thinking and reduced analytical reasoning, especially when religious beliefs are extrinsically motivated (used for social gain or comfort).

- People may engage in belief perseverance, resisting contrary evidence to preserve existing worldviews.

- Religious dogma, threats of blasphemy, and enforced repetitive rituals can function similarly to mind control, discouraging independent thought and dissent.

That said, some religious educators argue that faith and reason need not be mutually exclusive. In pluralistic classrooms, critical thinking can foster spiritual depth, ethical discernment, and respect for diverse beliefs. A balanced religious education can cultivate intellectual humility alongside moral conviction.

3. Comparative Religious Ethics

Religions across the world articulate rich, diverse moral systems. While differing in cosmology and metaphysics, many converge on shared human values such as compassion, truthfulness, justice, and self-restraint.

Buddhist Ethics: The Path of Sīla

In Buddhism, morality (śīla) is not imposed from above but arises naturally from inner clarity and compassion. It is one of the three pillars of the path to liberation, alongside meditation and wisdom. The Buddha’s ethical teachings emphasize nonviolence, right livelihood, and renunciation of craving. The Five Precepts guide laypeople, while the Sixteen Bodhisattva Precepts provide a nuanced ethical framework for Soto Zen priests—focusing not only on restraint but on benefiting all beings.

Unlike many Western traditions where morality implies duty or obligation, Buddhist ethics is self-reflective and voluntary, aimed at reducing suffering (dukkha) through intentional conduct rooted in insight.

Hindu, Chinese, and Abrahamic Moralities

- Hindu morality is rooted in dharma—duty according to one’s nature and station in life—and emphasizes karma, compassion, and devotion.

- Chinese moral philosophy, particularly in Confucianism, stresses filial piety, ritual decorum, and virtuous leadership. Daoism adds a more spontaneous, naturalistic ethic.

- Jewish ethics draws from the Torah and rabbinic literature, with a strong emphasis on justice (tzedek), law (halakha), and community covenant.

- Christian ethics, especially from the teachings of Jesus, emphasize love, forgiveness, humility, and the Sermon on the Mount as a moral high point. Monastic figures like St. Benedict established moral rules for spiritual life, while various denominations promote differing moral visions.

Across these traditions, ritual, narrative, law, and mysticism all contribute to ethical reflection. However, when insulated from critique, these same systems can justify exclusion, patriarchy, and even violence.

4. The Critique of Religion as a Catalyst for Moral Growth

Historically, critiques of religion have spurred moral progress. Philosophers from the Enlightenment onward have challenged the legitimacy of religious authority over ethics. Figures like Voltaire, Spinoza, Kant, and Nietzsche argued that morality must be grounded in reason, not revelation. Modern humanist movements emphasize empirical evidence, universal dignity, and moral autonomy—especially in secular societies.

Criticism of religious belief does not inherently imply hostility toward religious individuals. Rather, it aims to distinguish ethics from dogma, and to protect individual conscience from coercion.

As shown in Science Abbey’s analyses of Christianity and other traditions, it is often the case that moral insight flourishes when freed from the fear of heresy. Open, critical engagement with religious belief—whether from within or without—can enrich both ethical clarity and spiritual maturity.

5. Beyond “God”: A Scientific Humanist Perspective

The question “Do you believe in God?” is, in many ways, too vague to be meaningful. The term “God” encompasses everything from a personal deity to an abstract force, from mythic figures to pantheistic unity. As such, meaningful dialogue begins with clarification.

From a Scientific Humanist perspective, the real question is not “do you believe?” but:

- What do you observe?

- What do you trust as evidence?

- How do your beliefs impact others?

- Does your worldview support human flourishing and truth?

Many Scientific Humanists affirm a sense of awe, mystery, and unity in the cosmos. They may speak of “faith” not in the supernatural, but in the potential of reason, the value of compassion, and the search for meaning. This approach upholds the Golden Rule—treating others as oneself would wish to be treated—not as a religious edict but as a principle of empathy and reciprocity.

Moral Architecture: Freemasonry and the Science of the Good

1. Freemasonry: A Beautiful System of Morality

Freemasonry is often described, in its own ritual language, as “a beautiful and profound system of morality, veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols.” While neither a religion nor a philosophy in the academic sense, Freemasonry functions as an ethical initiatory tradition that fosters moral development, spiritual symbolism, and civic virtue. It is among the clearest historic expressions of what we might now call secular humanist morality in symbolic form.

Freemasonry teaches that human beings ought to be moral, charitable, upright, and reasonable—regardless of religion or creed. Members are encouraged to fulfill obligations to God (as they understand God), their nation, their fellow humans, and themselves. The framework is universal yet particular, civic yet spiritual.

Core Masonic Symbols and Their Moral Meaning:

- The Three Great Lights: the Book of the Law (scripture), the Square (ethical action), and the Compasses (self-restraint and spiritual aspiration). These represent the harmonious integration of faith, ethics, and discipline.

- Wisdom, Strength, and Beauty: The three moral pillars of the lodge, symbolizing intellectual discernment, moral courage, and the aesthetic harmony of a life well lived.

- Faith, Hope, and Charity: The three principal theological virtues represented on the ladder to Heaven. Charity, in particular, is emphasized as the cornerstone of Masonic morality.

- The Square and Compasses: Representing the balance between the earthly and the celestial, or between civic life and moral restraint.

- The Common Gavel: Symbolic of the moral imperative to shape and refine one’s character by removing the vices and superfluities of life.

- The Checkered Mosaic Pavement: The dual nature of life—joy and sorrow, light and dark—and the ethical responsibility to rise above duality through moral clarity.

In Masonic teaching, every Mason is metaphorically a builder of the spiritual temple—a “house not made with hands, eternal in the heavens.” This process of self-construction is universal and perpetual, and the lodge is a symbolic space for its cultivation. It is a monastery without walls, grounded in fraternity, liberty, equality, and reason.

2. Humanist Religion and the Science of the Good

While traditional religion is often predicated on divine authority and unquestioned doctrine, Scientific Humanism seeks to develop a rational, ethical, and spiritual worldview grounded in observation, reflection, and human well-being. This does not preclude spirituality but reframes it around the search for truth, the cultivation of virtue, and the celebration of life.

At its heart is a guiding moral idea: The Good.

The Structure of the Good:

- The One and the Law – The universal foundation of order, rationality, and harmony.

- The Cosmos – The entirety of space-time and all it contains.

- The Elements – The foundational constituents of reality: energy, matter, form.

- The Sun – Source of light, warmth, and biological life.

- The Earth and Atmosphere – The domain of ecological interdependence.

- Life Itself – The phenomenon of organic being, dynamic and self-aware.

Each level of Good corresponds to a natural order and a moral imperative. To serve the hyperbiosphere—the total integrated living system of Earth—is to serve the Good of oneself and others.

The Good Person:

The Scientific Humanist moral vision moves from the macrocosm to the microcosm through levels of social organization:

- The Good Soul: oriented toward noble ideals.

- The Good Citizen: committed to justice.

- The Good Teammate: marked by integrity.

- The Good Family Member: demonstrating piety and care.

- The Good Individual: cultivating virtue in thought and action.

This hierarchical ethic is not authoritarian—it is aspirational, encouraging the individual to harmonize personal development with collective well-being.

3. The Practice of the Good Religion

Scientific Humanist spirituality is neither supernaturalist nor nihilist. It affirms that:

- Life is finite, and therefore precious.

- The soul is the integrated pattern of one’s actions, thoughts, and relationships—a phenomenon of consciousness arising in the brain but influencing the world beyond the body.

- There is no afterlife as conceived by major religions, only transformation. The energy of life returns to nature, and the ethical residue of one’s deeds lives on in memory, culture, and consequence.

This spirituality finds expression through:

- Contemplation and Meditation – Training the parasympathetic nervous system to align thought and action with the Good.

- Invocation and Worship – Not as supplication, but as celebration and alignment with ideals.

- Goal-setting and Ethical Action – The formulation of personal and communal goals rooted in the pursuit of harmony, health, and happiness.

- Chant and Ritual – The poetic recitation of the Names of the Good—qualities and archetypes that remind practitioners of what is worth living and striving for.

In this way, an Integrated Humanist religion or spiritual path offers a coherent and scientific cosmology, a psychologically integrative worldview, and a spiritually fulfilling ethical system—without requiring supernatural belief.

4. Morality Without Myth: The Soul in Scientific Humanism

The soul, in this framework, is not a ghost or a substance. It is the totality of life as experienced and expressed by an organism. It is:

- Embodied: rooted in biological processes.

- Temporal: beginning at birth, ending at death.

- Ethical: composed of choices, consequences, and awareness.

The ideal soul is the whole cosmos in harmonious form. Each mortal soul reflects a unique fragment of that totality. Human consciousness—through reason, empathy, and discipline—can emulate the divine by aspiring toward this ideal.

“The soul is the entire life of an organism from birth to death… part of the single whole divine, eternal soul which is common to all living things.”

The goal is not personal immortality, but integration: to harmonize the self moment by moment, day by day, with the Good, the community, the biosphere, and the cosmos. To live ethically, rationally, and beautifully is the greatest offering.

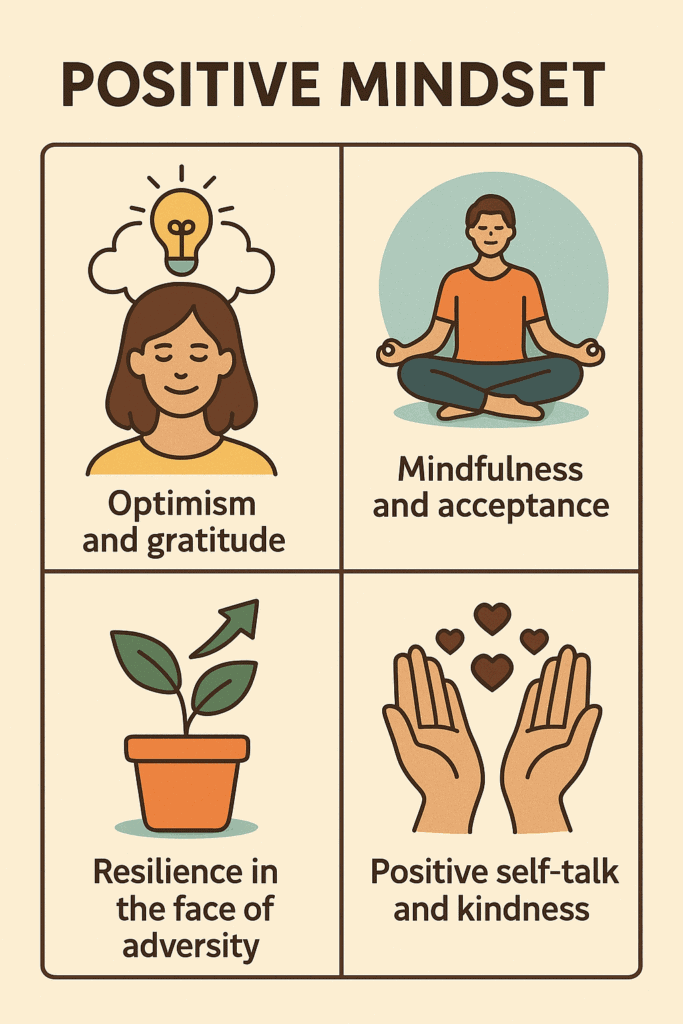

On Character: The Science of Moral Integrity and Ethical Strength

Character is the living bridge between moral ideals and moral action. It is the foundation of our ethical responses, the pattern of our emotional regulation, and the form our dignity takes in the world.

1. The Power of Perspective and the Positive Mind

A positive mindset is not naive optimism—it is the conscious practice of interpreting events through a lens of possibility, resilience, and constructive meaning. In secular moral systems, such as Scientific Humanism, positivity is not about denying suffering but about cultivating the capacity to act ethically even in adverse circumstances. This includes:

- Cognitive reframing

- Cultivation of gratitude and curiosity

- Focus on solutions rather than complaints

- An evidence-based sense of hope

This attitude fuels emotional strength and constructive social behavior.

2. Emotional Intelligence and Maturity

Emotional intelligence (EQ) refers to the ability to recognize, understand, regulate, and constructively use one’s emotions and those of others. Emotional maturity builds on this by including:

- Patience and self-regulation

- Willingness to take responsibility for one’s emotions

- Compassionate communication

- Tolerance for complexity and ambiguity

- Self-awareness without self-centeredness

Emotional maturity is essential in developing moral judgment. A mature individual understands that excessive kindness can sometimes mask fear or insecurity, just as aggression may hide vulnerability. Morality demands context-sensitive responses—not rigid behavior.

3. The Myth of the “Nice Guy” and Gender Stereotypes

Common stereotypes—such as women preferring “bad boys” over “nice guys”—are often oversimplified and culturally biased. While traits such as confidence, assertiveness, and decisiveness are indeed attractive, these can coexist with kindness and emotional maturity. Healthy relationships depend not on dominance but on mutual respect, boundaries, and emotional resilience. The excitement associated with risk-taking should not be confused with moral or psychological strength.

In a Scientific Humanist view, gender stereotypes should be deconstructed through evidence and empathy, not reinforced through anecdote. Real attraction is based on dynamic compatibility, not evolutionary caricatures.

4. Non-Attachment and Relationship Realism

From a Buddhist and scientific humanist lens, love and relationship are not about possession. They are temporary, evolving connections—real, meaningful, and often impermanent. Emotional maturity means:

- Allowing love without control

- Practicing detachment without indifference

- Understanding that loss and conflict are natural

- Resolving disagreement with compassion and honesty

This is the moral strength of acceptance: remaining present, honest, and kind in the face of change.

5. The Ecology of Character: Virtue, Health, and Balance

Scientific Humanism recognizes character as an ecosystem. Good character arises when one’s psychological, physiological, and ethical dimensions are aligned:

- Virtue is ethical coherence.

- Health is physiological and psychological coherence.

- Wisdom is existential coherence—seeing the big picture.

Character, like a tree, grows from root principles—truth, compassion, reason—and flourishes in ethical sunlight. Its fruits are resilience, integrity, and joy.

The alchemical idea of balance—the integration rather than purification of opposing forces—expresses this insight. Character is not about being without anger or desire, but mastering and channeling these forces with wisdom.

6. Practical Wisdom and the Reality of Moral Complexity

Aristotle recognized that moral life often involves conflict among virtues. In real life, virtues such as loyalty, honesty, and courage may compete. A just person may have to break a promise; a kind person may need to speak hard truths.

Scientific Humanism follows this practical wisdom tradition:

- Justice is the highest virtue when survival and happiness conflict.

- Temperance governs passion; courage governs fear.

- Wisdom governs how to prioritize virtues in context.

This is why moral education is a lifelong practice: not rote rule-following, but cultivating character capable of moral discernment.

7. Training the Character: Attention and Discipline

Just as muscle forms through repetition and resistance, so does character. Character grows by:

- Setting goals that align with ethical values

- Practicing emotional regulation and non-reactivity

- Refining one’s world-view through critical reflection

- Cultivating awareness and attention through meditation

Visualization and introspection form mental channels; they shape our attention, memory, emotion, and identity. Character is not fixed—it is formed by habit and honed through effort.

8. Community, Organization, and Moral Evolution

We are not only individuals. Human beings shape and are shaped by communities. Moral development accelerates in ethical, mindful communities. Organizations like Science Abbey offer:

- Shared goals and secular rituals

- Critical discourse and support

- Ethical guidelines rooted in science and reason

- Opportunities for meaningful contribution

Scientific Humanist community emphasizes universal dignity, rational policy, and compassionate interaction. It is a spiritual community without dogma—a moral training ground for character in the modern world.

9. Toward Integrated Human Character

Ultimately, character is the integration of:

- Reason: critical thinking and self-knowledge

- Compassion: connection and care

- Discipline: action aligned with ideals

This integration enables the good life: a life of virtue, happiness, and meaningful contribution. In the language of the Science of Wholeness:

- Survival is the concern of biology

- Happiness is the domain of religion (or spiritual meaning)

- Justice belongs to politics

- Virtue is the subject of ethics

Together, these form the fabric of a life well lived. Character is not inherited—it is cultivated. It is the flowering of the human spirit under the guidance of moral reason, social wisdom, and the pursuit of the Good.

Game Theory and the Structure of Moral Choice

As our understanding of both biology and rational decision-making deepens, a compelling picture has emerged: morality is neither entirely innate nor entirely learned, but emerges through dynamic interactions between nature, nurture, and strategic behavior. One of the most illuminating approaches to this field is game theory—a mathematical framework originally developed to understand competitive and cooperative strategies in economics, but now widely applied to questions of morality, justice, and human cooperation.

1. The Nature and Nurture of Moral Behavior

Modern developmental science rejects the binary of “nature versus nurture” in favor of an interactionist model, where morality is shaped by genetic predispositions, neural development, environmental context, and cultural learning. From infancy, humans demonstrate an intuitive sense of fairness, empathy, and preference for prosocial behavior—yet these capacities are continuously sculpted by experience.

Rather than isolating innate versus acquired moral traits, scientists increasingly focus on developmental pathways: how moral cognition and moral emotions unfold over time through feedback loops between individual behavior, social norms, and ecological conditions【source: Psychology Today, 2022】. Game theory provides the quantitative scaffolding to model these interactions.

2. Game Theory: Modeling Moral Choice

Game theory explores decision-making in strategic contexts—situations where an individual’s outcome depends not only on their own choices but on the choices of others. This is precisely the kind of environment in which morality evolves: social life.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma: Cooperation vs. Self-Interest

In the classic Prisoner’s Dilemma, two players must independently decide whether to cooperate or defect. If both cooperate, they achieve a good outcome. If one defects while the other cooperates, the defector gains more—but if both defect, both suffer.

This dilemma mirrors many real-world moral challenges: whether to tell the truth, share resources, or sacrifice for a group. The key insight from repeated iterations of the game is that cooperation becomes evolutionarily stable when reciprocity and memory are introduced. That is, moral behavior can emerge and persist if individuals remember past interactions and are likely to encounter one another again.

Tit-for-Tat: An Emergent Moral Strategy

The strategy of Tit-for-Tat—cooperate first, then mimic your partner’s previous move—has proven to be remarkably robust in evolutionary simulations. It balances forgiveness with deterrence and rewards cooperation while punishing betrayal. This maps closely to moral systems that value fairness, accountability, and proportional justice.

3. Utilitarian Models: Decision Theory and Moral Trade-Offs

In moral philosophy, utilitarianism aims to maximize well-being or minimize suffering. Mathematically, this is often framed using decision theory and expected utility theory, where agents attempt to select the outcome with the greatest expected value.

- Expected Utility: When deciding between multiple actions, each with potential benefits and harms, we can estimate their expected outcomes weighted by probability and impact. For example, how much good will come from donating to one charity versus another? How much suffering is prevented by one policy compared to another?

- Social Welfare Functions: These models aggregate the preferences or utilities of individuals into a collective decision, aiming to optimize for fairness, equity, or overall well-being. While powerful, these models also reveal philosophical tensions—should we sacrifice a few for the good of the many?

4. Evolutionary Game Theory and Moral Evolution

Extending beyond classical game theory, evolutionary game theory explores how strategies evolve over time under the pressures of natural selection.

- Altruism and Kin Selection: Behavior that appears self-sacrificial can make sense when it benefits relatives who share genetic material. Mathematical models like Hamilton’s Rule show how altruistic traits can spread if the genetic payoff to relatives exceeds the cost to the altruist.

- Group Selection and Reciprocity: Groups that foster cooperation and moral behavior may outperform those that don’t, allowing these traits to persist. This is a plausible evolutionary route for traits like fairness, punishment of cheaters, and empathy to emerge at the societal level.

These models suggest that moral norms are not arbitrary—they are adaptive, especially in social species like humans. The Golden Rule is not just an ethical ideal, but an evolutionarily stable strategy in many social contexts.

5. Probability, Moral Luck, and Risk

Morality often grapples with uncertainty. The concept of moral luck describes how outcomes beyond our control influence moral judgment. Game theory and probability help to clarify such dilemmas.

Consider two drivers with equal recklessness—one causes a fatal accident, the other does not. From a utilitarian viewpoint, the outcomes differ drastically. From a deontological view, the intentions are identical. Mathematical models allow us to evaluate the expected moral risk—how much responsibility a person should bear based on action and probable outcome, not just final results.

This adds nuance to concepts of justice, helping to distinguish culpable negligence from tragic circumstance.

6. Ethical Dilemmas in Mathematical Thought: The Trolley Problem

The famous Trolley Problem—whether to divert a trolley to kill one person rather than five—can be approached using decision theory. Yet, what makes this problem enduring is not the math, but the moral discomfort it evokes.

Should we act to save the many, or refuse to cause harm directly? Models of risk, expected harm, and utilitarian calculus help frame the decision, but they don’t resolve the conflict between rules-based ethics (deontology) and outcome-based ethics (consequentialism).

Such dilemmas highlight the limits of models: ethical decision-making requires both quantitative clarity and qualitative wisdom.

7. Summary: Moral Strategy, Modeled

Mathematics and game theory do not replace moral philosophy, but complement it. They allow us to:

- Simulate outcomes of moral choices.

- Understand the evolution of ethical behavior.

- Predict cooperative strategies that stabilize trust and fairness.

- Quantify moral dilemmas involving risk, utility, and justice.

But the models rely on the values we embed: What outcomes do we prioritize? Whose welfare counts? When does fairness outweigh efficiency?

In the end, game theory and decision models are moral microscopes: tools for exploring complexity, testing scenarios, and refining judgment. They help make morality more conscious, rational, and transparent—but they cannot answer, on their own, the ultimate question: What is the good life, and how shall we live it?

Applied Ethics: Science, Community, and the Moral Test of Action

1. Community and the Ethical Domain

At the heart of any ethical worldview is the concept of community. From families to cities, nations to the human species, and even beyond—to ecosystems and future generations—ethics becomes real only when lived with and among others.

Community may be defined as:

A group of sentient beings sharing space, time, interdependence, and meaning—held together by shared goals, mutual recognition, and a web of moral responsibility.

Ethics emerges from this shared life. It is not only a private matter of conscience, but a public and interpersonal art—the art of living well together. The Integrated Humanist perspective recognizes that morality must be practical, pluralistic, and planetary: it should work in daily life, respect human diversity, and apply to all living systems.

2. The Promise and Pitfalls of Situational Ethics

Situational ethics—popularized by theologian Joseph Fletcher in the 1960s—suggests that love should be the only guiding moral principle, and that rules must bend to fit the context. It prioritizes individual discretion, flexibility, and intentions over law. Fletcher argued that “the most loving thing” is always the right thing, even if it contradicts religious or cultural norms.

Strengths:

- Recognizes the moral complexity of real-world situations.

- Avoids rigid legalism or moral absolutism.

- Values human empathy, intentions, and mercy.

- Provides a framework for case-by-case ethical reasoning.

Critique from an Integrated Humanist Perspective:

While situational ethics values compassion and contextual reasoning, it suffers from several significant limitations:

- Subjectivity and Moral Drift

Without shared standards, situational ethics easily descends into moral relativism. What is “loving” or “right” becomes whatever the actor feels in the moment. This creates a vacuum of accountability and opens the door to justification for unethical actions under the guise of care or context. - Lack of Universality

Morality, especially in pluralistic societies, needs consistent frameworks. Applied ethics must be usable not just by saints or sages, but by flawed, everyday people. Integrated Humanism argues for moral systems that are both context-sensitive and rule-guided—blending flexibility with structure. - Neglect of Consequences and Power

Situational ethics may ignore unintended consequences or the power dynamics that shape perception. What one actor sees as “loving” may be patronizing, coercive, or self-serving from another perspective. - Ethical Inflation

As ethicist Steven Mintz notes in “Situational Ethics Is Killing America” (2021), the rise of subjective, outcome-driven ethics has contributed to erosion in civic trust, increased polarization, and a decline in shared moral norms. Integrated Humanism warns against this atomization of ethics and instead advocates for a shared ethical language grounded in science, empathy, and justice.

3. The Integrated Humanist Approach to Applied Ethics

Integrated Humanism draws from reason, evidence, emotional intelligence, and democratic dialogue to apply ethics across the domains of life. It does not claim to have absolute answers, but insists on moral seriousness—that choices must be examined carefully, openly, and with concern for all affected.

A. Governance and Social Policy

Government is the institutional face of ethics in society. The laws we pass and the systems we maintain express what we collectively value.

- Integrated ethics in governance demands transparency, evidence-based policymaking, accountability, and universal human rights.

- It supports progressive taxation, universal healthcare, gender equality, and environmental justice—not as ideological stances, but as logical responses to human need and planetary limits.

- It opposes systems that benefit the few at the expense of the many, arguing that the legitimacy of any government depends on its capacity to reduce suffering and promote flourishing.

B. Medical and Health Ethics

Medicine is a realm of life, death, and human dignity. Ethical healthcare must balance individual autonomy with public health, economic efficiency with human compassion.

- Integrated Humanist bioethics advocates for:

- Universal access to healthcare.

- Clear consent procedures.

- Respect for bodily autonomy and reproductive rights.

- End-of-life dignity and the right to die under conditions of terminal suffering.

- Universal access to healthcare.

Integrated ethics recognizes the complexity of emerging issues—like genetic engineering, organ allocation, and AI-assisted diagnostics—and insists that scientific progress must serve the common good, not corporate profit or elite control.

C. Environmental and Ecological Ethics

Morality cannot stop at the human species. The biosphere is the foundation of all moral life. Integrated Humanism integrates ecocentric thinking into every ethical system.

- Pollution, climate change, extinction, and overconsumption are not just environmental issues—they are moral failures.

- We must extend our moral circle to include non-human animals, ecosystems, and future generations.

- Ethical decisions must include the long-term consequences of policy, industry, and consumption.

This means acting with planetary foresight: rethinking economics, rewilding ecosystems, promoting plant-based diets, and supporting clean energy as a moral imperative.

D. Artificial Intelligence and Digital Ethics

As algorithms, machine learning, and autonomous systems grow more powerful, new ethical frontiers emerge.

- Who is accountable for an AI’s decision?

- How should data privacy be protected in a surveillance economy?

- Should lethal autonomous weapons be banned?

- How can we prevent AI from amplifying bias and inequality?

Integrated Humanism approaches AI ethics with caution and clarity:

- Human dignity and agency must be preserved.

- AI must be transparent, auditable, and aligned with human values.

- Digital innovation should prioritize access, fairness, and human enhancement, not simply profit or control.

4. Toward a Moral Compass for the Planetary Age

In a world of accelerating change, applied ethics cannot be reactive—it must be principled, adaptive, and global. Integrated Humanism proposes a moral compass that balances:

- Scientific insight (what is real and effective),

- Human empathy (what is just and compassionate),

- Moral consistency (what is fair and coherent),

- and Civic wisdom (what works in diverse communities).

In contrast to situational ethics—which can fragment society into subjective enclaves—Integrated Humanism seeks integrated systems of behavior, thought, and governance.

We are not separate from one another or from the Earth—we are a single evolving system. The health of that system is the truest measure of morality in action.

The Aesthetic and Spiritual Dimensions of the Moral Life

Morality is not merely a calculus of harm and benefit, nor a set of rules to be obeyed out of duty or fear. It is also a path of beauty and meaning, expressed through the way we live, love, create, and contemplate. A full moral life engages not only the intellect and the conscience, but also the heart, the imagination, and the spirit.

Integrated Humanism holds that ethics must be aesthetic and spiritual to be complete—that morality must inspire and uplift, not only restrain or command. This is where the moral intersects with the poetic, the artistic, the transcendent.

1. Aesthetic Morality: The Beauty of the Good

There is a long tradition, from Plato to Confucius to 20th-century thinkers like Iris Murdoch, that links the Good with the Beautiful. This insight is neither sentimental nor abstract. It reflects a real phenomenon: that moral excellence is often experienced as aesthetic excellence—as clarity, harmony, grace, and depth.

- A just action is often beautiful in its courage or simplicity.

- A virtuous life is not just efficient but elegant—shaped like a well-crafted story.

- Artistic expressions—from sacred music to political murals—can embody moral truths that logic alone cannot convey.

Aesthetic engagement awakens empathy, refines perception, and offers a sense of participation in something greater than the self. This, too, is part of moral development.

2. The Moral Power of Ritual and Symbol

Symbols, metaphors, and rituals are not antithetical to science—they are essential to spiritual meaning-making. From the Masonic compasses and square to the Zen calligraphy brush, from the Stoic temple of reason to the symbolic mandala of the universe, rituals of form reflect inner discipline and intentionality.

In Integrated Humanism, rituals are not about pleasing supernatural beings, but about training perception, cultivating presence, and embodying ideals. They serve as moral reminders: tools for memory, mood, and mindfulness.

Examples include:

- Meditative practices that align the mind with compassion and clarity.

- Ceremonies of life transitions that bind community and affirm dignity.

- Artistic creation as a form of service or testimony to truth.

A moral system devoid of symbols or beauty may be efficient—but it is unlikely to be loved, remembered, or lived.

3. Spirituality Without Superstition

Spirituality, in the Integrated Humanist sense, does not require belief in the supernatural. It arises from:

- Wonder at existence

- Awareness of impermanence

- The felt sense of connection to other beings and to the cosmos

To be spiritual is not to escape the world, but to engage it with reverence and perspective.

From the cosmic awe of Carl Sagan to the contemplative silence of a Zen monk, the spiritual impulse is a moral one—it humbles the ego, expands the circle of concern, and calls us to integrity.

This spirituality can be practiced through:

- Silence and solitude

- Music and poetry

- Ethical self-discipline

- Service to others

- Study of the natural world

It replaces fear with curiosity, guilt with responsibility, and dogma with dialogue.

4. Toward an Integrated Spiritual-Moral Practice

A flourishing life is not one of moral compliance alone. It is a life of wholeness, where thought, action, and feeling are aligned with the truth of our interdependence and the beauty of existence.

From this perspective, the science of morality must include the arts of moral living:

- The cultivation of character and temperament

- The aesthetic shaping of daily life

- The symbolic and spiritual practices that link us to one another, to the Earth, and to the ultimate mystery of being

Morality, in its highest form, is not merely doing what is right—it is becoming someone whose life radiates meaning, dignity, and love.

In the words of the philosopher Alain de Botton: “A good life is one lived in the spirit of beauty, truth, and consolation.”

Conclusion: Toward a Science of Morality

The science of morality is not a final answer, but a map of questions: How should we live? What is right? What is good? It is a field where biology, psychology, mathematics, philosophy, and lived experience converge. The integrated approach presented in this essay affirms that morality is not an invention, but a discovery—unfolding within nature, reason, and the human heart.

We have seen that morality emerges from multiple dimensions:

- From the evolutionary roots of empathy and cooperation.

- From the philosophical structures of virtue, justice, and duty.

- From the historical codes and aspirations of religious and secular traditions.

- From the mathematical clarity of game theory and decision models.

- From the ritual, symbolic, and aesthetic practices that embed values into life.

- And from the spiritual insight that sees the self not as a closed ego, but as part of a greater, interconnected whole.

The Moral Compass

At the core of Integrated Humanism is the belief that we can orient ourselves by a moral compass based not on superstition or absolute authority, but on:

- Observation – What is true?

- Empathy – What causes suffering or flourishing?

- Consistency – What rules or principles apply to all?

- Responsibility – What are the consequences of our actions?

- Aspiration – What kind of world do we want to build?

This compass guides not just personal conduct but collective policy. It grounds political systems, educational models, environmental planning, and economic justice in an ethical worldview that is rational, universal, and compassionate.

A Call to Moral Integration

To live morally is not merely to follow rules. It is to harmonize thought, feeling, and action. It is to understand the science of health, life, and cooperation—and to embody this understanding in how we love, labor, vote, teach, create, and rest.

We are moral beings not by creed but by capacity. Each of us, whatever our background, can learn to think more clearly, feel more deeply, and act more wisely. We can train our conscience as we train our muscles or minds. We can build character as we build relationships, slowly and through effort.

Toward a Moral Future

In the age of global interdependence, ecological crisis, and technological transformation, the stakes of moral failure are immense. The survival of human civilization—and the thriving of all life on Earth—now depends on whether we can build a shared ethical culture that transcends division and ignorance.

Science Abbey and similar projects are part of this global awakening. They do not ask us to abandon spiritual longing, but to re-ground it in reality, inquiry, and ethical practice. They ask us to live as science monks—scholars and citizens whose daily path is shaped by mindfulness, humility, and the courage to change.

Let this be our legacy:

Not temples to dogma, but sanctuaries of thought.

Not empires of ideology, but communities of conscience.

Not blind faith, but informed love.

“Do unto others as you would have them do unto you,” not because a deity commands it, but because you have seen the other in yourself.

This is the way of the Good. This is the moral life.