Table of Contents

- Preface: Why Philosophy Matters Today

- Chapter 1: From Myth to Philosophy – The Origins of Worldview

- Chapter 2: The Axial Age – Awakening the Philosophical Mind

- Chapter 3: Greek and Hellenistic Wisdom – Logos and the Soul

- Chapter 4: Mysticism, Metaphysics, and the World Beyond

- Chapter 5: Philosophy Across Faiths – Jewish, Christian, and Islamic Thought

- Chapter 6: Indian and Chinese Philosophical Traditions

- Chapter 7: The Renaissance and the Rebirth of Human Dignity

- Chapter 8: Reason and Revolution – Early Modern Thought

- Chapter 9: Enlightenment, Kant, and the Critique of Reason

- Chapter 10: 19th Century Visions – Will, History, and Liberation

- Chapter 11: 20th Century Thought – Crisis, Freedom, and Structure

- Chapter 12: East Meets West – Toward a Global Philosophy

- Chapter 13: Philosophy in the Age of Intelligence

- Epilogue: Integrated Humanism – A Philosophy for the Planetary Future

Preface: Why Philosophy Matters Today

Philosophy is not an academic luxury—it is a vital human activity. In every civilization, at every time, people have asked: What is real? What is right? What is meaningful? What should I do? These questions are not peripheral—they are foundational. They shape how we govern, educate, heal, and coexist.

Today, the world faces challenges that are as philosophical as they are political, scientific, or economic:

How do we define truth in the age of information? What are our obligations to the planet, to future generations, and to one another? Can technology enhance or erode our humanity? What moral framework can sustain freedom and justice in a pluralistic world?

This work is a response to these questions. It is a chronologically and thematically organized journey through the world’s philosophical traditions—Eastern and Western, ancient and modern, spiritual and secular. It reveals not a single unified system but a great dialogue—a shared human effort to understand reality and live wisely within it.

The hope is not to reduce all traditions to one or to choose a winner among them, but to illuminate their depth, beauty, and interconnection. We aim to recover the philosophical impulse: the courage to think, the discipline to question, and the imagination to envision a better world.

This is a story not just of philosophers, but of philosophy itself—as a companion, a mirror, and a guide to our collective becoming.

Chapter 1: From Myth to Philosophy – The Origins of Worldview

Introduction

Before there were philosophers, there were storytellers. Long before reasoned argument, formal logic, or dialectical inquiry, human beings sought to understand their place in the cosmos through myth, ritual, and symbol. These early efforts were not irrational; they were symbolically ordered, deeply intuitive attempts to harmonize life with the forces of nature, death, and the divine.

The emergence of philosophy as a distinct human endeavor did not arise in opposition to myth, but rather through its transformation. Philosophy begins when we move from “what is the story we belong to?” to “what is the nature of reality, and how can we know it?” This chapter explores how myth gave rise to philosophy, and how early civilizations—especially in Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, China, and the ancient Mediterranean—laid the symbolic and conceptual groundwork for humanity’s long philosophical journey.

I. Mythic Consciousness: The First Worldviews

1. The Purpose of Myth

In pre-literate and early literate cultures, myth was not fiction—it was a living system of explanation, encoding cosmic origins, social roles, moral rules, and spiritual meaning. Myths taught how the world began, why suffering exists, and what the gods demand. They offered answers to humanity’s most urgent questions: Who are we? Why do we die? What does the universe want from us?

“In the beginning…” is not just the start of a story—it is the beginning of metaphysics.

2. Mythic Traditions Around the World

• Mesopotamia:

The Epic of Gilgamesh (c. 2100 BCE) stands as the world’s oldest epic poem—and a proto-philosophical meditation on mortality, friendship, and the quest for eternal life. It dramatizes the first known literary confrontation with death as the boundary of human meaning.

• Ancient Egypt:

Egyptian texts such as the Book of the Dead and Pyramid Texts describe a highly structured afterlife, where the soul is judged by truth (Ma’at). Egyptian worldview was cosmic, moral, and ritualistic—centered on alignment with eternal order.

• Zoroastrian Persia:

In the Gāthās of Zoroaster, we find one of the earliest clear expressions of moral dualism—a cosmic battle between truth (asha) and falsehood (druj), with humanity participating through ethical choice.

• The Hebrew Prophetic Tradition:

The Tanakh, especially in books like Genesis, Ecclesiastes, and Job, introduced a moral monotheism that emphasized justice, covenant, and the mystery of divine will. Though religious, it engaged in existential questioning: What is suffering? What is righteousness?

• Indian Mythic Frameworks:

The Rig Veda, Mahabharata, and Ramayana blend myth, cosmology, and dharma (moral duty). These vast epics provided the basis for later systematic metaphysics in the Upanishads and schools of Indian philosophy.

• Chinese Cosmological Order:

Early Chinese worldview, seen in the I Ching (Book of Changes), expressed a philosophy of dynamic balance: yin and yang, the five elements, and cosmic cycles. Human ethics and nature’s rhythms were seen as intertwined.

II. The Threshold: From Myth to Philosophy

1. Logos Emerges from Mythos

In the 6th century BCE, thinkers in multiple regions began offering explanations of reality based not on mythic genealogy but on rational principles. This shift—from mythos (story) to logos (reasoned word)—did not erase the sacred, but sought to understand it through questioning, observation, and debate.

The earliest philosophers were still religious in spirit, but they dared to ask:

- What is the origin of all things?

- Can we know reality through reason?

- What is virtue and how should one live?

2. The Birth of Systematic Inquiry

• In India, the Upanishads (c. 700–500 BCE) began questioning ritualism, asserting that the essence of the self (ātman) is identical to the ultimate reality (Brahman). This non-dualistic insight birthed Vedanta and shaped Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist thought for millennia.

• In China, Confucius (c. 551–479 BCE) emphasized ethical life and social harmony grounded in the cultivation of virtue (ren, li), while Laozi and Zhuangzi pointed toward the Dao—the nameless way of nature and spontaneity. These paths, although divergent, shared an underlying concern with order and authenticity.

• In Greece, early thinkers like Thales, Heraclitus, and Pythagoras began replacing divine genealogies with abstract principles (water, fire, number, logos). Socrates (470–399 BCE), through his relentless questioning, made philosophy inseparable from the ethical examination of life.

III. Philosophy as the Inheritance of Myth

Philosophy did not destroy myth—it inherited, transformed, and internalized it. The gods became archetypes; rituals became meditations; epics became metaphors for the soul’s journey. In cultures across the globe, philosophers emerged not in spite of religion and myth but through them, asking deeper questions of the stories their ancestors told.

Thus, philosophy was born not merely as a rejection of the sacred, but as a more conscious engagement with it—a new way of relating to truth, to self, and to the cosmos.

Conclusion: The Ongoing Awakening

The turn from myth to philosophy was not a one-time event—it is a recurring threshold. In every age, and in every culture, there are those who ask deeper questions of the stories they inherit. They seek not just belief, but understanding. Not just tradition, but truth.

Philosophy begins wherever a human being wonders deeply, questions honestly, and seeks wisdom with courage. That spirit—first lit in the ancient world—continues to burn.

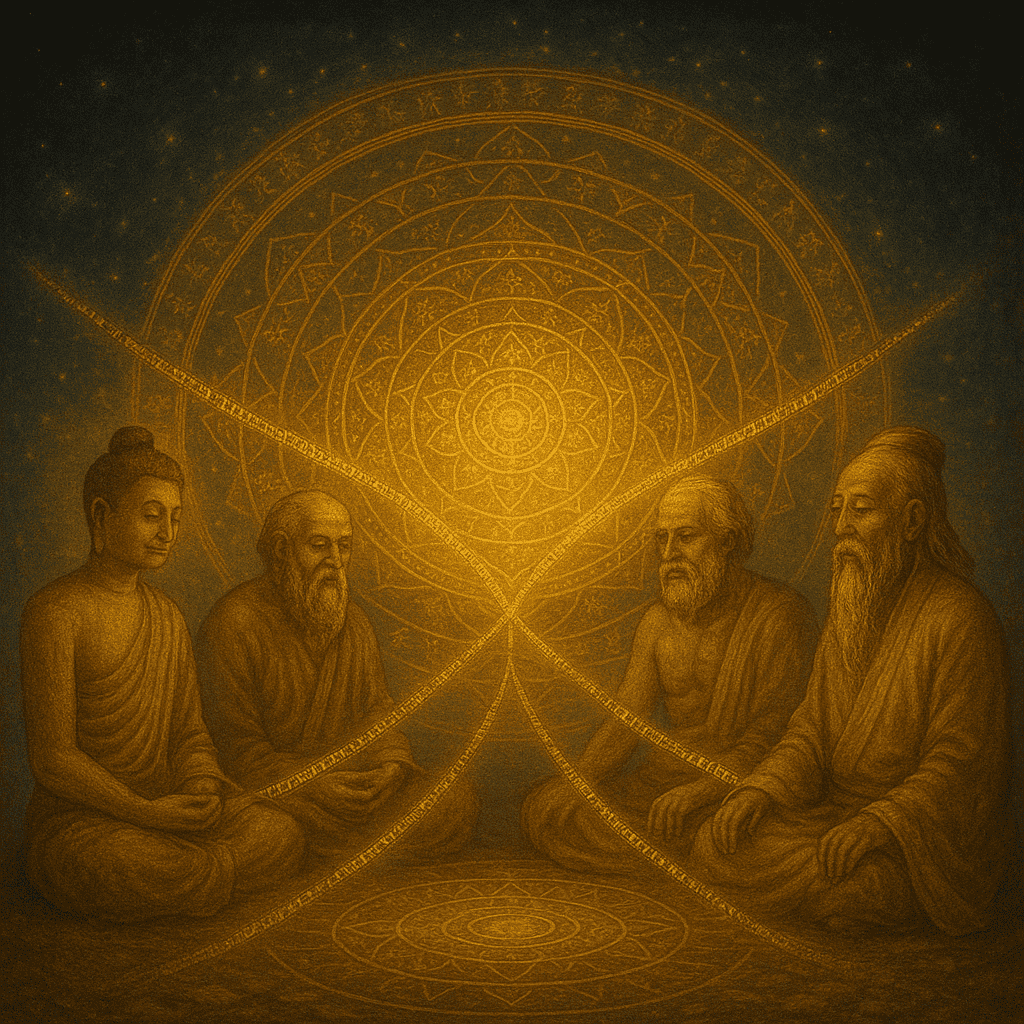

Chapter 2: The Axial Age – Awakening the Philosophical Mind

Introduction

Around the first millennium BCE, human history experienced a seismic cultural shift. Across regions as diverse as India, China, Persia, Greece, and the Levant, a new type of thought emerged—one that questioned inherited myths, scrutinized ethical life, and sought universal truths through reflection and reason. This period, later called the Axial Age by German philosopher Karl Jaspers, marked the awakening of what we now call philosophy.

The Axial Age (c. 800–200 BCE) did not produce a single worldview, but a plurality of world-transforming insights. Its thinkers were not content with local tribal deities or ritual repetition; they sought the eternal, the transcendent, the just, and the true. Whether through reason, introspection, meditation, or ethical cultivation, these figures challenged humanity to rise to a new level of consciousness.

I. The Concept of the Axial Age

1. Karl Jaspers’ Thesis

In The Origin and Goal of History (1949), Jaspers proposed that the Axial Age represents the first conscious reflection of humanity upon itself:

“The spiritual foundations of humanity were laid simultaneously and independently… and these are the foundations upon which humanity still subsists today.”

Jaspers noted that in this era:

- The self became distinct from the cosmos.

- Moral universals replaced tribal codes.

- Rational critique emerged alongside mystical insight.

- Human beings discovered conscience, transcendence, and individual interiority.

This transformation did not occur uniformly, but it echoed across civilizations in deeply resonant ways.

II. India: The Inner Cosmos and the Path of Liberation

1. The Upanishads and Non-Dualism

The Upanishads, composed between 700–500 BCE, mark the shift from ritual-based Vedic religion to metaphysical introspection. These texts explore the nature of the self (ātman) and its unity with the ultimate reality (Brahman).

Key themes include:

- The illusion (māyā) of separateness

- The transmigration of the soul (samsāra)

- Liberation (moksha) through knowledge and detachment

This interiorized metaphysics laid the groundwork for Vedanta and other classical Indian systems.

2. The Buddha and the Middle Way

Siddhartha Gautama, the historical Buddha (c. 563–483 BCE), rejected both Vedic ritualism and extreme asceticism. Through direct insight, he articulated:

- The Four Noble Truths

- The Eightfold Path

- The doctrine of dependent origination

- The concept of non-self (anattā)

Buddhism emphasized impermanence, compassion, and the cessation of suffering through ethical action and meditative discipline.

3. Mahavira and Jainism

Contemporary to the Buddha, Mahavira (c. 599–527 BCE) founded Jainism, a path of radical non-violence (ahimsa) and self-liberation through strict ethical purity, asceticism, and the metaphysics of the soul (jīva).

III. China: Virtue, Harmony, and the Way

1. Confucius and Ethical Humanism

Confucius (Kongzi, 551–479 BCE) sought to restore order in a time of political chaos. Rather than look to heaven for miracles, he grounded virtue in human relationships, tradition, and moral cultivation.

Core concepts:

- Ren: humaneness or benevolence

- Li: ritual propriety and social harmony

- Xiao: filial piety

- Junzi: the ideal noble person

His teaching emphasized self-improvement, respect, and ethical leadership—ideas that became central to East Asian civilization.

2. Laozi and the Dao

Attributed to Laozi, the Daodejing offers a contrasting vision: harmony with the Dao (Way), which cannot be grasped or named. Daoism teaches:

- Wu wei: effortless action

- Ziran: naturalness or spontaneity

- The paradox of opposites: soft > hard, still > forceful

Daoism does not argue or analyze—it points to a deeper wisdom through poetic paradox and surrender to the rhythms of nature.

3. Zhuangzi and the Liberation of Perspective

Zhuangzi (c. 369–286 BCE) playfully dismantles the notion of fixed reality or absolute knowledge. Through dreamlike parables, he questions:

- Whether the self is permanent

- Whether values are universal

- Whether distinctions are real or conventional

His work celebrates freedom, relativism, and joyful detachment.

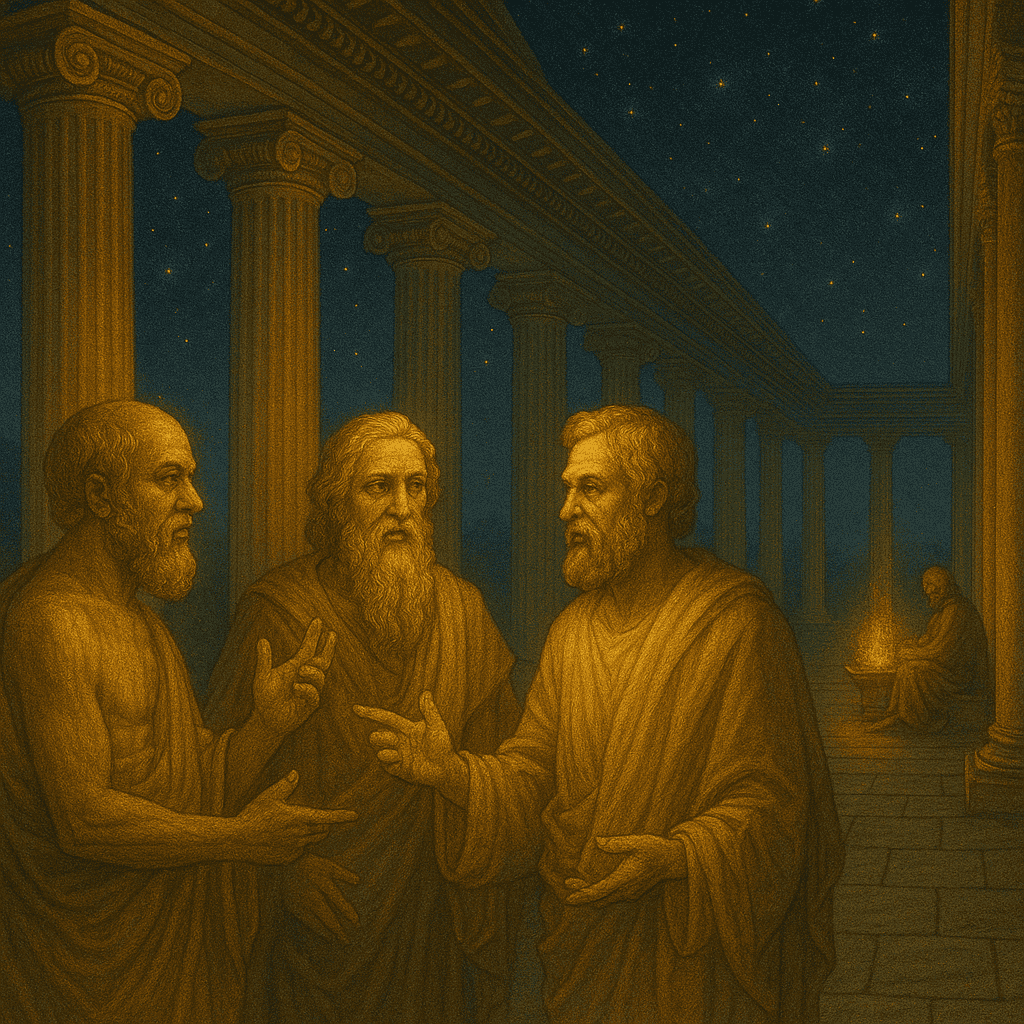

IV. Greece: Reason, Ethics, and the Love of Wisdom

1. The Presocratics

Before Socrates, Greek thinkers turned from myth to natural principles:

- Thales: all is water

- Heraclitus: change is the fundamental reality (panta rhei)

- Pythagoras: number and harmony underlie the cosmos

- Parmenides: change is an illusion; being is one

These thinkers set the stage for cosmology, logic, and metaphysics.

2. Socrates and the Examined Life

Socrates (470–399 BCE) never wrote a word, but transformed philosophy through conversation. He taught that:

- Wisdom begins in knowing one’s ignorance

- The unexamined life is not worth living

- Virtue is knowledge, and wrongdoing is ignorance

His method of relentless questioning (elenchus) became the foundation of critical thinking.

3. Plato and the World of Forms

Plato (427–347 BCE) systematized Socratic thought in dialogues exploring:

- The world of Forms: eternal, perfect realities

- The tripartite soul and its virtues

- The ideal philosopher-king and just society

- Dialectic as the method of ascent to truth

He fused ethics, politics, metaphysics, and mysticism into a unified vision.

4. Aristotle and the Systematization of Knowledge

Aristotle (384–322 BCE), Plato’s student, grounded philosophy in empirical observation and logic:

- Developed formal logic

- Defined categories of being

- Outlined ethical life as the pursuit of eudaimonia (flourishing)

- Linked ethics, politics, biology, and metaphysics into a coherent system

His influence on both Western and Islamic thought would be monumental.

V. Common Themes Across Civilizations

Despite profound cultural differences, Axial Age thinkers converged on several ideas:

- Self-reflection as a path to transformation

- Universal moral principles beyond tribal boundaries

- Transcendence of the physical or social order

- A search for truth, harmony, and justice

- Emphasis on wisdom as a life practice, not mere theory

These developments represent a global turning point in human consciousness: the moment when humanity, across civilizations, began to question not just how to survive, but how to live wisely.

Conclusion: The Birth of Philosophy as a Global Phenomenon

The Axial Age gave rise to the world’s enduring philosophical traditions—Hindu Vedanta, Jainism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Daoism, and Western philosophy. Each system asked in its own way:

What is the nature of reality? What is the good life? What is the self?

These questions would echo through the centuries, giving birth to the vast, diverse, and interwoven tapestry of global philosophy.

Chapter 3: Greek and Hellenistic Wisdom – Logos and the Soul

Introduction

If the Axial Age opened the door to philosophical consciousness, it was classical Greece that walked boldly through it. Nowhere in the ancient world was reason elevated with such intensity as in the Greek world of the 5th to 3rd centuries BCE. Here, philosophy not only asked what is real and what is good—it became a disciplined method of rational inquiry, logical argument, and public discourse.

The Greeks gave us many of the central categories of philosophy still in use today: metaphysics, ethics, logic, epistemology, and political theory. But they also grappled deeply with the mysteries of the soul, cosmos, and the meaning of life. This chapter traces the rise of classical Greek philosophy through Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, and follows its transformation through the Hellenistic schools, which made philosophy into a way of life.

I. The Pre-Socratics: Wonder and the World

The earliest Greek thinkers—known collectively as the Pre-Socratics—rejected mythic explanations in favor of cosmic principles. They were the first to ask not “who made the world?” but “what is it made of?”

1. Milesian Naturalists

- Thales (c. 624–546 BCE): posited water as the first principle of all things

- Anaximander: introduced the apeiron, the boundless, as the origin of existence

- Anaximenes: proposed air as the foundational substance

2. Pythagorean Harmony

- Pythagoras (c. 570–495 BCE): saw number as the ultimate structure of reality

- Introduced ideas of metempsychosis (reincarnation) and moral purification through mathematics, music, and contemplation

3. Change and Permanence

- Heraclitus (c. 535–475 BCE): taught that all is flux (panta rhei) and that logos, the rational principle, underlies all change

- Parmenides (c. 515–450 BCE): argued that change is illusion, and that only being truly is

- Empedocles, Anaxagoras, Democritus: developed early theories of pluralism, mind, and atomism

These thinkers planted the seeds of both natural science and metaphysical speculation.

II. Socrates: The Turn Inward

1. The Philosopher of Virtue

Socrates (470–399 BCE), though he wrote nothing, became the iconic figure of Western philosophy. Known through the works of Plato and Xenophon, Socrates shifted the philosophical gaze from cosmology to ethics and the human soul.

- His motto: “The unexamined life is not worth living.”

- He used elenchus—the method of questioning—to expose contradictions in people’s beliefs

- Believed that virtue is knowledge, and wrongdoing results from ignorance

- His death by hemlock for “corrupting the youth” made him a martyr of free thought

2. Philosophy as Dialogue

Socrates’ legacy is not a system, but a method: a model of dialogical inquiry and ethical courage.

III. Plato: Reality and the World of Forms

Plato (c. 427–347 BCE), Socrates’ student, created the first true philosophical system in the West. Through dramatic dialogues, he explored nearly every domain of philosophy.

1. The Theory of Forms

Plato distinguished between:

- The changing world of appearances

- The unchanging world of Forms (Ideas), such as Justice, Beauty, Goodness

Knowledge, for Plato, is not empirical—it is recollection of eternal truths known by the soul before birth.

2. The Soul and Its Ascent

- The soul has three parts: rational, spirited, and desiring

- Justice occurs when these are in harmony

- In the Phaedrus and Republic, the soul’s journey is likened to a charioteer guiding two horses, aspiring to the realm of Forms

3. Political Philosophy

In The Republic, Plato describes:

- The ideal city, ruled by philosopher-kings

- A tripartite class system mirroring the soul

- Education as the soul’s turning toward the Good

Plato fused metaphysics, ethics, politics, and epistemology into a powerful philosophical vision.

IV. Aristotle: The Science of Being

Aristotle (384–322 BCE), Plato’s student, rejected the Theory of Forms in favor of empirical realism. He systematized knowledge into disciplines still taught today.

1. Logic and Categories

- Founded formal logic through syllogisms and deductive reasoning

- Defined ten categories of being (substance, quality, quantity, etc.)

2. Metaphysics and Substance

- Reality is composed of substances, each with form and matter

- Change is explained by potentiality and actuality

- The ultimate cause of motion is the Unmoved Mover, pure actuality

3. Ethics and the Good Life

- Happiness (eudaimonia) is the goal of life

- Achieved through the cultivation of virtue (aretē) via moderation (the golden mean)

- Ethics is practical, aimed at flourishing in community

4. Politics and Society

- Humans are political animals

- The best state supports moral development

- Advocated constitutional government as the most stable form

Aristotle’s influence extended across centuries, shaping Islamic, Christian, and modern Western thought.

V. The Hellenistic Schools: Philosophy as Therapy

After Alexander the Great’s conquests, Greek philosophy spread across the Mediterranean and Near East. As political instability grew, philosophy turned inward again—becoming a spiritual practice and way of life.

1. Stoicism

- Founded by Zeno of Citium; later developed by Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius

- The universe is rationally ordered by logos

- Live in accordance with nature and reason

- Practice apathy (apatheia): freedom from destructive emotions

- Emphasis on duty, resilience, and moral clarity

2. Epicureanism

- Founded by Epicurus

- The goal is pleasure, defined as the absence of pain and fear

- Rejects superstition and divine punishment

- Advocates for friendship, moderation, and tranquility

3. Skepticism

- Pyrrho and later Sextus Empiricus taught suspension of judgment (epochē)

- True peace comes from realizing that certainty is impossible

4. Cynicism

- Inspired by Diogenes of Sinope

- Advocated for radical simplicity, shamelessness, and rejection of material values

- Satirized social conventions to reveal hypocrisy

These schools focused on personal transformation, anticipating later religious and spiritual movements.

Conclusion: Logos and the Legacy of the Soul

Greek and Hellenistic philosophy brought reason, dialogue, and the pursuit of inner harmony to the forefront of human thought. Through Plato’s Forms, Aristotle’s categories, and the Stoic logos, the Greeks developed a language of universal truth, grounded in both the order of the cosmos and the formation of character.

Their questions remain our questions:

- What is justice?

- What is the soul?

- How should one live?

In the next chapter, we will see how these ideas would be absorbed, transformed, and transfigured by the mystical, religious, and metaphysical traditions of late antiquity and beyond.

Chapter 4: Mysticism, Metaphysics, and the World Beyond

Introduction

As the classical Greek world gave way to the Hellenistic and Roman empires, a profound transformation overtook the philosophical landscape. In the face of cultural upheaval, political decline, and spiritual longing, many thinkers turned away from rational dialectic alone and toward the inner mysteries of being. The result was an era of deep metaphysical speculation, mystical ascent, and the synthesis of philosophical inquiry with sacred tradition.

This period gave rise to powerful traditions such as Neoplatonism, Hermeticism, and Gnosticism. Far from being mere esoteric curiosities, these movements carried forward some of the most profound and enduring philosophical themes: the nature of the divine, the hierarchy of reality, the soul’s journey, and the meaning of inner transformation.

I. Neoplatonism: From the One to the Soul’s Return

1. Plotinus and the Hierarchy of Being

The greatest philosophical system of late antiquity was articulated by Plotinus (c. 204–270 CE), whose teachings were compiled by his student Porphyry in the Enneads.

At the heart of Neoplatonism lies a triadic metaphysics:

- The One (to hen): the source of all being, beyond being and intellect

- Nous: the divine intellect, containing the eternal Forms

- Psyche: the world soul, linking spirit and matter

All things emanate from the One through processes of overflow (emanation), and the goal of human life is to return to the source through contemplation, purification, and inner ascent.

“The One is not a being, but the source of being—it is beyond all categories.” – Plotinus

2. Porphyry, Iamblichus, and the Theurgic Path

- Porphyry (c. 234–305) defended philosophical monotheism and ethical vegetarianism

- Iamblichus (c. 245–325) added the element of theurgy—ritual practices meant to unite the soul with divine forces

- Emphasized the role of divine intermediaries (gods, daemons, angels)

Neoplatonism became the dominant intellectual framework of late antiquity, influencing Christian, Islamic, and Jewish philosophy for centuries.

II. Hermeticism: Wisdom from the Divine Mind

1. The Corpus Hermeticum

Ascribed to Hermes Trismegistus—a syncretic fusion of the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth—the Corpus Hermeticum is a series of mystical-philosophical dialogues written between the 1st and 4th centuries CE.

Key themes:

- The cosmos as a living, divine organism

- Humanity as a microcosm reflecting the macrocosm

- Ascent of the soul through stages of purification and knowledge

- The goal: gnosis—inner, transformative knowledge of the divine

Hermeticism fused Platonic metaphysics, Stoic cosmology, Egyptian ritual, and Hellenistic mysticism, and would later deeply influence Renaissance philosophy, alchemy, and early science.

2. Alchemical Symbolism and Inner Transformation

- Alchemy in the Hermetic tradition was not merely proto-chemistry—it was a symbolic language of inner change

- Zosimos of Panopolis (3rd–4th century) described the alchemical process as a metaphor for the death and resurrection of the soul

“Knowledge of self is the beginning of divine knowledge.” – Hermetic maxim

III. Gnosticism: Knowledge and Liberation

1. The Gnostic Vision

Gnosticism was a diverse set of religious-philosophical movements that emerged in the early Christian era. It taught that the world is flawed or fallen, created by an ignorant or malevolent being (the Demiurge), and that the divine spark within humans must be awakened through gnosis.

Central ideas:

- Radical dualism between spirit and matter

- The soul as an exiled fragment of the divine

- Salvation through knowledge, not faith or obedience

- Mythic cosmologies of aeons, emanations, and cosmic descent

2. Key Texts and Sources

- The Gospel of Thomas, The Gospel of Truth, Pistis Sophia

- The Nag Hammadi Library, discovered in 1945, brought many lost Gnostic texts to light

While often declared heretical by orthodox Christian authorities, Gnosticism represents a distinct philosophical voice: one of cosmic alienation, interior revelation, and spiritual rebellion.

IV. Philosophical Religion: The Integration of Reason and Revelation

1. Philo of Alexandria

Philo (c. 20 BCE–50 CE) was a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher who fused Platonic metaphysics with Jewish theology. He introduced the concept of the Logos as the divine intermediary between God and creation, a notion that would later be central to Christian theology.

2. Early Christian Thinkers

Early Christian philosophers drew heavily from Platonism:

- Origen (c. 184–253): emphasized pre-existent souls and the allegorical interpretation of scripture

- Augustine (354–430): combined Platonic introspection with Christian doctrine

- Explored the nature of time, will, memory, and the inner path to God

- Asserted that truth resides within the soul, guided by divine illumination

- Explored the nature of time, will, memory, and the inner path to God

“You were within me, but I was outside myself… and in my unloveliness I fell upon lovely things.” – Augustine, Confessions

V. The Legacy of Mystical Metaphysics

This era gave philosophy a vertical dimension—a vision of ascent, return, illumination, and unity. It transformed reason from an abstract faculty into a spiritual instrument for transcending ordinary consciousness. Whether in Neoplatonic contemplation, Hermetic gnosis, or Gnostic rebellion, late antiquity insisted that philosophy is not only about thinking—it is about becoming.

Themes that endured include:

- Hierarchies of being: from matter to spirit, soul to source

- The soul’s divine origin and journey of return

- The interplay of knowledge, purification, and liberation

- The cosmic dignity of the human being as mediator between worlds

Conclusion: The Ladder Between Heaven and Earth

In late antiquity, philosophy was not merely a discourse—it was a path. These mystical-metaphysical systems provided humanity with some of its most profound symbols of transformation. They taught that truth is not merely known, but lived—that we do not just think our way to wisdom, we must become it.

In the coming chapters, we will explore how these traditions shaped the great religious and philosophical systems of the Middle Ages, as the inheritance of Greek reason met the revelations of monotheistic faiths, transforming world philosophy once again.

Chapter 5: Philosophy Across Faiths – Jewish, Christian, and Islamic Thought

Introduction

As the Roman world fragmented and transformed, philosophy did not disappear. It migrated—eastward, southward, inward, and upward. With the rise of monotheistic religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—philosophy entered into a new and complex relationship with revelation, tradition, and divine law.

Rather than abandoning reason, many of the greatest religious thinkers of the medieval world sought to unite rational inquiry with revealed truth. Drawing heavily on Plato, Aristotle, Plotinus, and other classical thinkers, these philosophers shaped theological doctrines, legal systems, ethical ideals, and metaphysical visions that still influence billions today.

This chapter explores the shared and divergent paths of Jewish, Christian, and Islamic philosophy from the early centuries of the Common Era through the high Middle Ages.

I. Jewish Philosophy – Law, Reason, and the Hidden Light

1. Early Developments

Jewish thinkers in the Greco-Roman world, especially Philo of Alexandria (c. 20 BCE – 50 CE), laid early foundations by combining Platonic metaphysics with Jewish theology. He introduced the Logos as the intermediary between God and creation—a concept later echoed in Christian theology.

2. Medieval Jewish Rationalism

• Saadia Gaon (882–942)

- Defended monotheism and divine justice against dualist sects

- Argued that reason and revelation must ultimately agree

- Affirmed creation ex nihilo and the immortality of the soul

• Solomon Ibn Gabirol (c. 1021–1058)

- Influenced both Jewish and Christian thought

- Argued that divine will and matter are intermediary substances in creation

• Maimonides (Moses ben Maimon) (1138–1204)

- Author of Guide for the Perplexed, one of the greatest works of Jewish philosophy

- Synthesized Aristotle and rabbinic law

- Described God as pure intellect, beyond human categories

- Advocated negative theology: we can only say what God is not

- Stressed ethical rationalism, and the gradual perfection of the human soul

Jewish philosophy was deeply concerned with the tension between law and reason, particularism and universality, and the hidden, transcendent nature of the divine.

II. Christian Philosophy – Logos and Divine Order

1. Church Fathers and Early Synthesis

Early Christian theology absorbed and adapted Platonic and Stoic ideas:

- Justin Martyr, Clement of Alexandria, and Origen emphasized the Logos as the rational ordering principle of the universe

- Augustine of Hippo (354–430), a former Neoplatonist, brought Christian theology to philosophical maturity

• Augustine’s Key Contributions:

- God as timeless being, source of all truth

- Evil as privation, not substance

- The soul’s inner journey toward divine illumination

- Deep reflections on memory, time, and selfhood (Confessions)

2. Scholasticism and the Rise of Christian Rationalism

By the 12th century, Christian thinkers had access to Aristotle through Islamic translations. This gave rise to scholasticism: a method of systematic theology rooted in dialectical logic.

• Anselm of Canterbury (1033–1109)

- Formulated the ontological argument for God’s existence

• Peter Abelard (1079–1142)

- Promoted dialectical method and ethical intentionalism

• Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274)

- Synthesized Aristotle and Christian doctrine in the Summa Theologica

- Defined natural law, analogical language, and the five ways to prove God’s existence

- Separated faith and reason without contradiction: reason leads us to truth; revelation completes it

“Grace does not destroy nature, but perfects it.” – Aquinas

Christian philosophy emphasized that reason, faith, and love are not adversaries, but lenses through which divine truth is progressively revealed.

III. Islamic Philosophy – Falsafa and Illumination

1. The Translation Movement and the Birth of Islamic Philosophy

With the expansion of the Islamic world after the 7th century, the caliphates became custodians of the ancient world’s wisdom. During the 9th–10th centuries, the House of Wisdom in Baghdad and other centers translated Greek texts—especially Aristotle and Plotinus—into Arabic.

This led to the emergence of falsafa: a school of rational philosophy conducted within an Islamic framework.

2. Key Figures of Falsafa

• Al-Kindi (c. 801–873)

- Known as the “First Philosopher of the Arabs”

- Integrated Greek thought into Islamic theology

- Argued for God as a simple, necessary being beyond time and matter

• Al-Farabi (c. 872–950)

- Synthesized Plato and Aristotle

- Described the ideal state as one governed by a philosopher-prophet

- Emphasized emanation and the importance of intellectual virtue

• Avicenna (Ibn Sina) (980–1037)

- Created a vast system of metaphysics, logic, psychology, and medicine

- Defined God as necessary existence

- Proposed the “flying man” thought experiment to show the soul’s independence from the body

- His ideas dominated Islamic, Jewish, and Christian scholasticism for centuries

• Al-Ghazali (1058–1111)

- Criticized Avicennian metaphysics in The Incoherence of the Philosophers

- Argued that divine will, not necessity, governs the cosmos

- Revived Sufi spirituality, emphasizing direct experience of God over speculative reason

• Averroes (Ibn Rushd) (1126–1198)

- Reaffirmed Aristotelian rationalism

- Wrote commentaries on Aristotle that shaped Latin Christian philosophy

- Advocated the “double truth” theory: religion for the masses, reason for philosophers

3. Illuminationist and Mystical Philosophers

• Suhrawardi (1154–1191)

- Founded the school of Illuminationism (Ishrāq)

- Blended Neoplatonic metaphysics with Persian mysticism

- Emphasized light as the metaphysical principle of being

Islamic philosophy was thus a cosmic and rational tradition, spanning metaphysics, ethics, law, and mysticism—unified by the quest to harmonize the eternal truths of reason with the revelations of the Qur’an.

IV. Shared Themes and Enduring Questions

Though differing in language, doctrine, and metaphysics, Islamic, Jewish, and Christian philosophy shared certain core concerns:

- How can finite minds approach infinite truth?

- Is reason subordinate to revelation, or are they complementary?

- What is the nature of God, and can we know it?

- What is the moral purpose of the human soul?

Each tradition maintained its theological boundaries while also fostering deep philosophical inquiry, legal reasoning, ethical systems, and cosmic metaphysics. These faith-informed philosophies prepared the ground for modern science, political theory, and secular ethics—even as they continue to shape religious thought today.

Conclusion: Between Faith and Reason

Medieval philosophy was not a retreat from rationality—it was an expansion of reason into the realms of eternity, law, and revelation. It took the insights of Greek metaphysics and asked: What if the world is not just rational, but also sacred? What if truth must be sought both in the mind’s light and in the light that transcends it?

In the next chapter, we turn east once more—to examine how the great systems of Indian and Chinese philosophy evolved in dialogue with spirituality, ethics, and inner liberation.

Chapter 6: Indian and Chinese Philosophical Traditions

Introduction

While the Western world developed philosophy through a trajectory of rationalism, metaphysics, and theological synthesis, the Indian and Chinese traditions cultivated parallel but distinct systems grounded in contemplation, moral cultivation, social harmony, and liberation. These were not merely philosophical disciplines in the academic sense—they were systems of life, deeply woven into culture, ritual, and spiritual practice.

From the metaphysical subtleties of the Upanishads to the disciplined realism of Confucian statecraft, these traditions offered powerful and coherent responses to the central philosophical questions of the human condition:

What is real? How should we live? What is the nature of the self? What is liberation?

I. Indian Philosophy: The Science of Liberation

1. The Six Classical Darśanas (Viewpoints)

Indian philosophy matured into six major orthodox schools, each with its own answers to metaphysical, epistemological, and ethical questions. These schools accepted the authority of the Vedas but interpreted them differently.

• Nyāya – Logic and Epistemology

- Developed rigorous systems of inference, debate, and proof

- Defined valid knowledge (pramāṇa) as perception, inference, comparison, and testimony

• Vaiśeṣika – Atomism and Metaphysical Realism

- Proposed that reality is composed of indivisible atoms and categories like substance, quality, action

• Sāṃkhya – Dualism and Cosmology

- Divided reality into Purusha (consciousness) and Prakriti (matter)

- Liberation comes from discriminating knowledge between the two

• Yoga (Patañjali) – Discipline of Liberation

- Outlined the Eight Limbs of Yoga, including ethics (yama), meditation (dhyāna), and absorption (samādhi)

- Emphasized control of the mind to transcend suffering

• Pūrva Mīmāṃsā – Ritual and Dharma

- Focused on the ritual authority of the Vedas

- Ethical action (karma) upholds cosmic order

• Vedānta – Ultimate Unity

- Most influential of the six schools

- Teaches that Ātman (self) is identical with Brahman (absolute reality)

- Major branches include:

- Advaita Vedānta (non-dualism – Śaṅkara): world is illusion (māyā), only Brahman is real

- Viśiṣṭādvaita (qualified non-dualism – Rāmānuja): Brahman includes diversity within unity

- Dvaita (dualism – Madhva): God and soul are eternally distinct

- Advaita Vedānta (non-dualism – Śaṅkara): world is illusion (māyā), only Brahman is real

2. Buddhism: Impermanence, Emptiness, and Compassion

Though often seen as non-theistic, Buddhism evolved into one of the world’s most sophisticated philosophical systems, with major branches including Theravāda, Māhāyāna, and Vajrayāna.

• Core Concepts:

- Anicca (impermanence), Dukkha (suffering), Anattā (non-self)

- The Four Noble Truths and Eightfold Path

- Karma and rebirth without eternal soul

• Mahāyāna Philosophy:

- Nāgārjuna (c. 150–250 CE): founder of Madhyamaka school

- All phenomena are empty (śūnyatā) of inherent existence

- Ultimate truth is beyond all concepts

- All phenomena are empty (śūnyatā) of inherent existence

- Vasubandhu, Asaṅga: founders of Yogācāra (“Mind-Only”)

- Reality is constructed by consciousness

- Liberation involves purifying the mind-stream

- Reality is constructed by consciousness

- Dignāga, Dharmakīrti: advanced Buddhist epistemology and logic

• Zen and Vajrayāna:

- Zen (Chan in China) emphasizes direct experience, meditation, and the spontaneity of insight

- Vajrayāna (Tibetan Buddhism) adds ritual, mantra, and visualization as paths to realization

II. Chinese Philosophy: Harmony, Order, and the Way

1. Confucianism: Ethics as Social Order

Founded by Confucius (551–479 BCE), Confucianism shaped the moral, political, and educational foundations of China and East Asia.

• Core Principles:

- Ren (benevolence): love and compassion expressed in action

- Li (ritual): propriety, etiquette, and respect for tradition

- Xiao (filial piety): honoring one’s parents and ancestors

- Junzi: the “noble person” who leads by moral example

Confucianism views morality as relational and hierarchical, focused on self-cultivation, harmony, and the rectification of names (calling things and roles what they truly are).

2. Daoism: Flowing with the Way

Daoism, attributed to Laozi (Daodejing) and developed by Zhuangzi, offers a mystical-philosophical path of non-action (wúwéi), spontaneity, and harmony with nature’s rhythms.

• Core Insights:

- The Dao is the ineffable source of all reality

- Human suffering comes from contrivance and interference

- The sage is like water: flexible, yielding, and unstoppable

Daoism values non-duality, natural simplicity, and a playful freedom from artificial structures. It provides a counterpoint to Confucian structure—yet both are seen as complementary in Chinese tradition.

3. Legalism and Mohism: Practical Alternatives

- Legalism (Han Feizi): believed human nature is selfish; society must be controlled by law, punishment, and reward

- Mohism (Mozi): promoted universal love, meritocracy, and anti-ritualism

Though overshadowed by Confucian orthodoxy, these schools offered pragmatic and utilitarian approaches to social governance.

III. Chinese Buddhism and the Synthesis of Traditions

1. The Arrival and Transformation of Buddhism

Buddhism arrived in China during the Han Dynasty and merged with native philosophies to form distinct Chinese schools.

• Major Chinese Schools:

- Tiantai: emphasized the Lotus Sutra, universal Buddha-nature

- Huayan: metaphysics of interpenetration—“one in all, all in one”

- Chan (Zen): meditation-centered, iconoclastic, direct pointing to the mind

Chinese Buddhism developed a unique metaphysical and ethical flavor, blending Indian ideas with Daoist intuition and Confucian moralism.

2. The Rise of Neo-Confucianism

By the Song Dynasty (960–1279), thinkers like Zhu Xi and Wang Yangming rearticulated Confucianism by integrating:

- Buddhist introspection

- Daoist cosmology

- Metaphysical moral principles (the li, or principle, and qi, vital energy)

Neo-Confucianism became the dominant intellectual framework in East Asia for centuries.

IV. Shared Themes and Philosophical Insights

Despite their diversity, Indian and Chinese traditions converge on several profound themes:

- Ethics as inner cultivation: Virtue is a practice, not a rulebook

- Reality as dynamic and interdependent: Everything is process, relation, and transformation

- The self as fluid or illusory: Liberation often requires transcending the ego

- Philosophy as soteriology: Wisdom is a path to freedom, not just an explanation

Whereas Western philosophy often privileged truth as proposition, these traditions focus on truth as realization.

Conclusion: The Way of Harmony and Liberation

Indian and Chinese philosophies offer humanity some of its oldest, richest, and most sophisticated visions of wisdom. They do not ask merely what is true, but how to live, how to perceive, and how to be free.

In the next chapter, we return to the West—where the Renaissance and early modern thinkers sought to reclaim ancient sources, revive human dignity, and usher in a new era of reason, exploration, and individualism.

Chapter 7: The Renaissance and the Rebirth of Human Dignity

Introduction

The Renaissance—from the Italian rinascita, meaning rebirth—was more than an artistic flowering. It was a philosophical awakening. In the ruins of medieval scholasticism and amid the new vitality of urban centers, thinkers across Europe began to recover and reinterpret the texts of antiquity, rediscovering not only the forms of classical art and science but the ideals of human reason, dignity, and potential.

From the 14th to the 16th century, this movement expanded from Italy to the rest of Europe, blending Christian theology, Platonic metaphysics, Civic virtue, and Hermetic mystery into a powerful affirmation of human worth and intellectual freedom. In this chapter, we explore the humanist ethos, the revival of ancient wisdom, and the emergence of the modern self.

I. Humanism and the Revival of Classical Learning

1. Petrarch and the Birth of Humanism

Francesco Petrarch (1304–1374) is often called the “Father of Humanism.” A passionate reader of Cicero, he championed:

- A return to the studia humanitatis—grammar, rhetoric, poetry, history, and moral philosophy

- The value of the individual conscience and interiority

- A break with scholastic logic in favor of personal reflection and ethical living

For Petrarch, philosophy was not a theological exercise but a mode of self-cultivation.

2. Civic Humanism and Political Ethics

Later thinkers such as Leonardo Bruni, Coluccio Salutati, and Niccolò Machiavelli extended humanism into the sphere of politics. Civic virtue was grounded in:

- Engagement with public life

- The idea of the active citizen

- Revival of Roman ideals of liberty, prudence, and strength

While Petrarch looked inward, Civic Humanists looked outward—to cities, republics, and human institutions as the proper arena of virtue.

II. The Renaissance Synthesis: Philosophy, Art, and Spirit

1. Pico della Mirandola and the Dignity of Man

In 1486, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494) wrote his Oration on the Dignity of Man, often called the “Manifesto of the Renaissance.”

He argued:

- That human beings have no fixed nature, but are endowed with the freedom to become like beasts or gods

- That philosophy should synthesize Plato and Aristotle, Moses and Zoroaster, Hermes and Christ

- That true wisdom transcends sectarian boundaries

Pico’s 900 theses aimed to reconcile all systems of thought—Greek, Hebrew, Christian, Arabic—into a universal vision of divine-human potential.

2. Erasmus and Christian Humanism

Desiderius Erasmus (1466–1536) brought humanist scholarship into dialogue with Christian reform:

- Translated and edited the New Testament with philological precision

- Advocated for inner piety over ritual and reasoned faith over dogma

- Critiqued church corruption in In Praise of Folly, blending satire with moral seriousness

Erasmus exemplified the Renaissance ideal: a scholar of antiquity, a reformer of religion, and a friend to both faith and reason.

III. The Hermetic and Esoteric Renaissance

1. Marsilio Ficino and the Revival of Platonism

Marsilio Ficino (1433–1499), under the patronage of the Medici in Florence, translated:

- The complete works of Plato

- The Corpus Hermeticum, ancient mystical texts attributed to Hermes Trismegistus

- Plotinus’s Enneads and other Neoplatonist works

Ficino’s Platonic Theology affirmed:

- The immortality of the soul

- The hierarchical cosmos as a ladder of ascent to the divine

- Love (eros) as a metaphysical force uniting all things

He combined Christian devotion with Platonic mysticism, helping to inaugurate a Platonic-Christian synthesis.

2. Hermetic Philosophy and Cosmic Magic

Hermeticism, as revived in the Renaissance, held that:

- The human microcosm mirrors the cosmic macrocosm

- Through gnosis, symbol, and ritual, the soul may ascend toward the divine source

- Nature is alive with divine correspondences—stars, metals, herbs, and words participate in a universal language

Key figures:

- Giovanni Pico della Mirandola: linked Kabbalah with Christian-Platonism

- Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa (Three Books of Occult Philosophy): detailed magical correspondences and occult science

- Paracelsus: developed a Hermetic approach to medicine, alchemy, and the spirit of matter

This esoteric current would influence not only mystics and alchemists, but also the scientific imagination in the coming centuries.

IV. The Crisis of Authority and the Seeds of Reform

The Renaissance also planted the seeds of religious and political reform:

- Individual conscience was elevated over dogmatic submission

- Access to ancient texts challenged scholastic orthodoxy

- The invention of the printing press (c. 1440) enabled widespread dissemination of radical and transformative ideas

Thinkers such as Thomas More (Utopia) questioned both the church and the emerging nation-state, imagining alternative social and political orders based on philosophical principles.

V. Themes and Legacies of the Renaissance

The Renaissance did not produce a single school of thought, but rather a new attitude toward knowledge, self, and society. Its core philosophical themes include:

- Human dignity and potential: the human being as a free, rational, and creative agent

- Synthesis over sectarianism: truth as universal and multifaceted

- Harmony between reason and faith: neither blindly dogmatic nor purely secular

- Recovery of ancient wisdom: Platonism, Neoplatonism, Hermeticism, Stoicism

- Emergence of modern individuality: interiority, authorship, self-invention

These themes shaped the trajectory of modern science, politics, ethics, and the very concept of human freedom.

Conclusion: From the Soul’s Likeness to the Cosmos to the Sovereignty of Thought

The Renaissance was not just a return to antiquity—it was a creative resurrection. By reviving the ancient sources of wisdom and reframing them through the lens of Christian spirituality and human autonomy, Renaissance thinkers redefined what it means to be human.

In the next chapter, we will see how these currents—reason, liberty, individuality—would lay the groundwork for the early modern world, as philosophers sought to construct new systems of knowledge, metaphysics, ethics, and political order on the foundation of rational inquiry and empirical observation.

Chapter 8: Reason and Revolution – Early Modern Thought

Introduction

The early modern period witnessed one of the most profound intellectual revolutions in human history. In the wake of the Renaissance and the upheavals of the Reformation, European thinkers began to reimagine the foundations of knowledge, power, society, and self. The collapse of medieval certainty, combined with the rise of empirical science and political instability, gave birth to a new philosophical worldview—one grounded in human reason, natural law, and the pursuit of autonomy.

This chapter explores the transformation from Renaissance synthesis to the Age of Reason. It traces the emergence of rationalism and empiricism, the birth of modern science, and the foundations of modern political and economic theory.

I. The Rationalist Tradition: Mind as the Key to Reality

1. René Descartes (1596–1650): Method and Certainty

Often regarded as the “Father of Modern Philosophy,” Descartes sought certainty in an age of doubt. In his Discourse on Method and Meditations on First Philosophy, he introduced a radical new approach:

- Cogito, ergo sum (“I think, therefore I am”): self-awareness as the foundation of knowledge

- Methodic doubt: systematically doubting all beliefs to find indubitable truth

- Dualism: mind (res cogitans) and body (res extensa) as distinct substances

- Emphasis on clear and distinct ideas as criteria for truth

Descartes launched the epistemological turn—focusing philosophy on how we know, rather than what we inherit.

2. Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677): Monism and Immanence

In his Ethics, Spinoza offered a bold, geometric vision of reality:

- God and Nature are one (Deus sive Natura)

- Everything is determined; free will is understanding necessity

- Ethical life arises through understanding the unity of all things

Spinoza’s pantheistic monism and radical critique of anthropomorphic religion made him a foundational figure of secular humanism and Enlightenment ethics.

3. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716): Harmony and Reason

Leibniz saw the universe as composed of monads—spiritual units of perception:

- The universe is governed by a pre-established harmony

- God chose the “best of all possible worlds”

- Reason and logic are the keys to metaphysics, mathematics, and ethics

Together, Descartes, Spinoza, and Leibniz formed the rationalist school, asserting that reason alone can discover the structure of reality.

II. The Empiricist Revolution: Knowledge from Experience

1. Francis Bacon (1561–1626): The New Science

Bacon rejected scholasticism and laid the foundations for empirical science in Novum Organum:

- Proposed the inductive method: gathering data to form general laws

- Critiqued the “idols of the mind”—biases that distort reasoning

- Called for the advancement of learning for the benefit of humanity

Bacon’s vision of science as a cooperative, experimental endeavor reshaped the modern world.

2. Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679): Mechanism and Authority

In Leviathan, Hobbes argued:

- Human nature is self-interested, competitive, and fearful

- Without a sovereign authority, life would be “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short”

- Just government arises from a social contract to ensure peace

Hobbes replaced divine right with political realism, founding modern secular political theory.

3. John Locke (1632–1704): Experience and Liberty

Locke countered both Descartes and Hobbes:

- In Essay Concerning Human Understanding, argued the mind is a tabula rasa (blank slate)

- All knowledge comes through experience and reflection

- In Two Treatises of Government, defended natural rights—life, liberty, property

Locke’s influence extended to education, science, and liberal democracy.

4. George Berkeley and David Hume

- Berkeley (1685–1753): asserted that reality is composed of perceptions in the mind of God

- Hume (1711–1776): skeptical empiricist who argued:

- Causality, self, and morality are not provable but habitual

- Reason is the slave of the passions

- Critiqued miracles and natural religion

- Causality, self, and morality are not provable but habitual

Hume’s radical empiricism laid the groundwork for modern skepticism and analytical philosophy.

III. The Scientific Revolution: Nature as Law and Language

This period saw the emergence of a new cosmology—mechanistic, lawful, and mathematical.

1. Key Figures:

- Nicolaus Copernicus: heliocentric universe

- Johannes Kepler: laws of planetary motion

- Galileo Galilei: telescopic observations, scientific method

- Isaac Newton: Principia Mathematica, universal gravitation, optics

2. Philosophical Significance:

- The universe is rational, intelligible, and mathematically structured

- Knowledge is gained through experiment, observation, and measurement

- Human beings are not at the center, but capable of understanding the whole

The Scientific Revolution inspired a vision of philosophy as a natural philosophy—integrating science, ethics, and metaphysics into a unified rational system.

IV. Political and Economic Philosophy in the Age of Reason

1. Rousseau and the General Will

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) critiqued the Enlightenment’s rationalism:

- Society corrupts natural innocence

- True freedom is obedience to a law one gives oneself

- Introduced the General Will: collective moral sovereignty

His ideas influenced both democracy and totalitarianism, and he remains central to debates on freedom, equality, and authenticity.

2. Montesquieu and Constitutional Liberty

Montesquieu (1689–1755), in The Spirit of the Laws:

- Advocated for separation of powers

- Compared legal systems to show how culture shapes law

- Argued that liberty requires checks and balances

3. Adam Smith and the Ethics of Capitalism

Adam Smith (1723–1790), in The Wealth of Nations:

- Proposed the invisible hand of the market

- Founded modern economics as a moral science

- In The Theory of Moral Sentiments, emphasized sympathy and virtue

Smith’s work helped define liberal political economy, merging ethics with market logic.

4. American Political Philosophy

The Enlightenment inspired revolutions:

- Jefferson, Madison, Hamilton: the U.S. Constitution as a product of Enlightenment reason

- Benjamin Franklin: rational moralism and practical wisdom

V. Themes and Transformations

The early modern period redefined philosophy by:

- Making reason, not authority, the basis of truth

- Shifting focus from God’s cosmos to human understanding

- Replacing final causes with efficient and mathematical laws

- Grounding politics in natural rights, not divine order

- Merging science and metaphysics into a unified worldview

Conclusion: Toward Enlightenment and Its Shadows

Early modern philosophy gave birth to the Enlightenment ideal: that humanity could understand the world, perfect society, and elevate the human condition through rational freedom.

Yet this same age also sowed the seeds of skepticism, alienation, and mechanical determinism—challenges that would confront 19th and 20th century thinkers in new and urgent ways.

In the next chapter, we follow the Enlightenment to its height and breaking point, as Immanuel Kant, Romantics, Idealists, and existential rebels wrestled with freedom, morality, reason, and the self.

Chapter 9: Enlightenment, Kant, and the Critique of Reason

Introduction

The 18th century Enlightenment represented the culmination of centuries of intellectual evolution. Fueled by the achievements of the Scientific Revolution, the confidence of humanism, and the political aspirations of liberal revolutions, Enlightenment thinkers believed that reason could illuminate every domain of human life—nature, society, religion, and morality.

Yet this unbounded faith in reason would also provoke its own reckoning. Immanuel Kant, perhaps the most influential philosopher of modernity, launched a powerful critique of pure reason—seeking to preserve rational inquiry by placing it within carefully defined limits. Through his synthesis of empiricism and rationalism, and his defense of moral autonomy, Kant ushered in a new era of critical philosophy that still defines many philosophical debates today.

I. The Enlightenment Project

1. Philosophical Optimism

Enlightenment thinkers across Europe championed:

- Universal reason as the foundation of truth

- Secular ethics based on natural law and human rights

- Progress through education, science, and reform

- Tolerance and the critique of superstition

2. Central Figures

• Voltaire (1694–1778)

- Master of satire and critique of religious intolerance

- Defended civil liberties, free speech, and human dignity

• Denis Diderot (1713–1784)

- Editor of the Encyclopédie, a monument to Enlightenment knowledge

- Promoted materialism, atheism, and intellectual freedom

• Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778)

- Critic of Enlightenment rationalism

- Argued that reason corrupts natural goodness

- Advocated freedom, equality, and a return to simplicity

• David Hume (1711–1776)

- Challenged rationalist certainty

- Questioned causality, selfhood, and religious belief

- Paved the way for Kant’s critical turn

3. Enlightenment and Revolution

- Inspired the American (1776) and French (1789) revolutions

- Articulated ideals of democracy, liberty, and secular governance

- Spread through salons, pamphlets, universities, and scientific academies

Despite its optimism, Enlightenment thought faced growing tensions:

- Between freedom and social control

- Between reason and feeling

- Between universal ideals and cultural difference

II. Immanuel Kant: Limits and Liberation

1. Kant’s “Copernican Revolution”

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) transformed modern philosophy by asking:

What are the conditions that make knowledge possible?

In his Critique of Pure Reason (1781), Kant argued:

- The mind does not passively receive the world; it actively structures experience

- Space, time, and causality are a priori forms through which we perceive phenomena

- We can never know the thing-in-itself (noumenon)—only its appearance (phenomenon)

This epistemological shift is called Kant’s “Copernican revolution”—instead of the mind revolving around objects, objects revolve around the mind’s structuring capacities.

2. The Moral Law Within

In Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals (1785) and Critique of Practical Reason (1788), Kant grounded ethics in autonomy:

- Morality arises from the rational will, not consequences or divine command

- The categorical imperative commands: “Act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.”

- Humans must be treated as ends in themselves, never as means

For Kant, true freedom is obedience to the moral law one gives oneself—the foundation of human dignity and moral duty.

3. The Critique of Judgment

In his Critique of Judgment (1790), Kant extended his philosophy to:

- Aesthetics: beauty as a free play of imagination and understanding

- Teleology: interpreting nature as if it had purposes (without assuming it does)

- Bridging the gap between the empirical world and moral reason

III. Key Contributions and Enduring Ideas

Kant synthesized and transformed:

- Rationalism (Descartes, Leibniz): knowledge from reason

- Empiricism (Locke, Hume): knowledge from experience

He created a new critical philosophy that:

- Limited metaphysical speculation to make room for freedom and faith

- Established human autonomy as the basis of ethics

- Laid the groundwork for modern liberal, secular morality

- Balanced science and freedom, determinism and moral choice

Kant’s thought deeply influenced:

- German Idealism (Fichte, Schelling, Hegel)

- Existentialism, phenomenology, and deontological ethics

- The development of modern liberal democracy, human rights, and education

IV. The Crisis and Promise of Enlightenment

1. The Limits of Reason

Despite its triumphs, Enlightenment philosophy began to reveal cracks:

- Rationalism could not fully account for emotion, art, or mysticism

- Scientific progress led to new alienation and mechanization

- Universal ideals often masked Eurocentrism and colonial ambition

Thinkers like Rousseau and later Romantics pushed back, arguing for:

- The value of nature, emotion, and individuality

- A deeper appreciation of historical context and cultural difference

2. The Dual Legacy

The Enlightenment left a dual legacy:

- It advanced science, secularism, liberty, and education

- But it also paved the way for technocracy, bureaucratic control, and moral abstraction

Kant’s work remains the pivot point—a balance of reason and humility, of universal ethics and epistemological restraint.

Conclusion: The Awakening of the Modern Mind

With Kant, philosophy reaches a new maturity: a recognition of both its power and its limits. The Enlightenment dream of reason survives, but only through self-critique. It becomes a philosophy not of dogma, but of discernment—a tool for freedom, not domination.

In the next chapter, we will see how 19th-century thinkers inherited, transformed, and often rebelled against Enlightenment ideals—as they wrestled with history, suffering, will, revolution, and the birth of the modern self.

Chapter 10: 19th Century Visions – Will, History, and Liberation

Introduction

The 19th century witnessed the emergence of philosophy’s modern face: critical, historical, psychological, and often defiant. While the Enlightenment had sought order in reason, the thinkers of this period confronted chaos, conflict, and contradiction.

Philosophy was no longer simply about truth and certainty—it became a battleground over history, will, freedom, alienation, and power. New systems of thought emerged in response to the Industrial Revolution, social upheaval, and scientific progress. The questions became existential, political, and deeply personal:

What does it mean to be free? What is consciousness? What is history’s purpose? What happens when God is no longer the anchor of meaning?

I. German Idealism – Spirit, History, and Absolute Freedom

1. Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762–1814)

- Expanded Kant’s notion of the self into a creative, self-positing “I”

- The ego confronts a non-ego (world) to define itself through struggle

- Philosophy as the unfolding of self-conscious freedom

2. Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (1775–1854)

- Proposed a philosophy of nature: nature as visible spirit, spirit as invisible nature

- Bridged science, aesthetics, and metaphysics

- Emphasized art as the ultimate revelation of the Absolute

3. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831)

- Developed the most ambitious system of dialectical philosophy in history

- Reality is a historical process of Spirit (Geist) coming to know itself

- Each stage of history represents a moment of consciousness unfolding

- Introduced the dialectic: thesis → antithesis → synthesis

- In Phenomenology of Spirit, explores alienation, recognition, and self-realization

- In Philosophy of Right, outlines the modern state as the rational embodiment of freedom

“The real is the rational, and the rational is the real.” – Hegel

II. Romanticism and the Revolt Against Reason

While Hegel saw history as orderly progression, others saw suffering, tragedy, and spiritual longing. The Romantics reacted against mechanistic rationalism, emphasizing:

- Emotion, intuition, and awe

- The sublime in nature and the individual soul

- The mystical and artistic dimensions of truth

This ethos would shape the rise of existentialism, depth psychology, and religious personalism.

III. Arthur Schopenhauer – Will and Suffering

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860) turned Hegel on his head:

- Argued that the Will, not reason, is the ultimate reality

- Human existence is driven by blind striving, resulting in suffering

- Aesthetic contemplation and compassion offer temporary escape

- Influenced Nietzsche, Freud, Wagner, and Buddhist philosophy in Europe

His The World as Will and Representation remains a landmark in pessimistic metaphysics.

IV. Søren Kierkegaard – Faith, Subjectivity, and the Leap

Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855), the “father of existentialism,” rejected both Hegelian system-building and abstract reason.

- Emphasized individual existence, anxiety, and authentic choice

- Saw truth as subjective, rooted in personal commitment

- In Fear and Trembling, explored the leap of faith as a paradox beyond ethics

- Critiqued Christendom for reducing faith to cultural conformity

Kierkegaard’s Christian existentialism influenced 20th-century theology and philosophy profoundly.

V. Karl Marx – Alienation and Historical Materialism

Karl Marx (1818–1883), in collaboration with Friedrich Engels, transformed Hegel’s dialectic into a critique of capitalist society.

- Introduced historical materialism: history as the struggle between classes

- Argued that human essence is expressed through labor

- In capitalism, workers become alienated from their labor, products, and self

- Predicted a revolution leading to a classless, communist society

Key works:

- The Communist Manifesto (1848)

- Das Kapital (1867)

Marx combined philosophy, economics, and politics into a revolutionary system of praxis.

VI. John Stuart Mill and the Ethics of Liberty

John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) advanced utilitarian ethics, social reform, and liberal individualism.

- In Utilitarianism, argued for the greatest happiness principle

- In On Liberty, defended freedom of speech, expression, and thought

- Advocated for women’s rights, education, and social equality

Mill helped establish modern frameworks of secular ethics, progressive politics, and human rights.

VII. Friedrich Nietzsche – Beyond Good and Evil

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) is perhaps the most provocative philosopher of the 19th century.

- Declared the “death of God” as the collapse of traditional values

- Critiqued Christian morality as a “slave morality” of resentment

- Promoted the Übermensch (Overman) as the creator of new values

- Introduced eternal recurrence: the challenge to affirm one’s life eternally

- Explored the will to power as the fundamental drive of life

Major works:

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra

- Beyond Good and Evil

- The Genealogy of Morals

Nietzsche rejected metaphysics, embraced art and affirmation, and laid the groundwork for existentialism, postmodernism, and cultural critique.

VIII. Shared Themes of 19th Century Philosophy

Across these varied thinkers, we find common themes:

- The centrality of the self, freedom, and inward struggle

- A focus on history, not as backdrop, but as a force shaping consciousness

- The critique of abstraction, systems, and dehumanizing institutions

- A shift from truth as system to truth as life

This was a century of visionary synthesis and rupture, preparing the way for psychoanalysis, existentialism, phenomenology, and critical theory in the 20th century.

Conclusion: Toward the Abyss and the Future

The 19th century gave philosophy its modern tensions:

- Between freedom and determinism

- Between reason and the unconscious

- Between morality and nihilism

It also gave birth to the modern individual—burdened with responsibility, longing for authenticity, and faced with a world no longer ordered by divine command.

In the next chapter, we will enter the 20th century, where existentialists, phenomenologists, analysts, and postmodernists grapple with a fragmented world—and attempt to rebuild meaning, language, and community on the edge of modernity.

Chapter 11: 20th Century Thought – Crisis, Freedom, and Structure

Introduction

The 20th century opened under the shadow of tremendous contradiction. Human reason, so celebrated in the Enlightenment, now produced both the atomic bomb and modern medicine, totalitarian states and universal human rights. Two world wars, global colonization and decolonization, and the rise of industrial, digital, and post-industrial economies forced philosophers to reconsider the foundations of knowledge, ethics, politics, and meaning.

In this fractured century, philosophy split into multiple traditions:

- Continental philosophers explored being, existence, language, and history

- Analytic philosophers sharpened logical precision and epistemic inquiry

- Others launched deep critiques of power, ideology, and identity

This chapter surveys the key movements and thinkers of this transformative century.

I. Phenomenology and Existentialism: Consciousness and Being

1. Edmund Husserl (1859–1938): Founder of Phenomenology

- Sought to describe conscious experience as it appears, without metaphysical assumptions

- Called for a “return to the things themselves”

- Introduced the method of bracketing (epoché) to suspend judgment about the external world

- Distinguished between noesis (act of consciousness) and noema (object as experienced)

Phenomenology became the basis for later existential, hermeneutic, and post-structuralist developments.

2. Martin Heidegger (1889–1976): Being and Time

- Critiqued the forgetting of Being in Western metaphysics

- Described human existence (Dasein) as being-toward-death

- Emphasized authenticity, temporality, and historicity

- Language is the “house of Being”—truth is not fixed but disclosed

Heidegger’s influence stretched across existentialism, theology, and postmodernism—despite controversies over his Nazi affiliations.

3. Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980): Existence and Freedom

- Declared that existence precedes essence: humans are not defined by nature but by action

- In Being and Nothingness, analyzed consciousness as lack, freedom, and responsibility

- Advocated radical freedom and moral commitment

- Defined bad faith as lying to oneself to avoid responsibility

4. Simone de Beauvoir (1908–1986): Gender and Liberation

- In The Second Sex, argued that “one is not born, but becomes, a woman”

- Critiqued patriarchal essentialism and argued for existential freedom for women

- Influenced feminist theory and ethics of care

5. Albert Camus (1913–1960): The Absurd and Revolt

- Explored the “absurd” condition: the clash between human meaning-seeking and a silent universe

- Advocated for lucid rebellion—engagement without metaphysical illusions

- In The Myth of Sisyphus, described life as meaningful in spite of its futility

II. Analytic Philosophy: Language, Logic, and Knowledge

1. Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) and G.E. Moore

- Sought to ground philosophy in logic and analysis of language

- Rejected Hegelian idealism

- Advocated for clear, commonsense reasoning

2. Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951)

• Early Wittgenstein (Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus):

- Language mirrors reality through logical form

- What can be said clearly can be said at all; “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent”

• Later Wittgenstein (Philosophical Investigations):

- Language is a social practice, embedded in “language games”

- Meaning arises from use, not reference

Wittgenstein’s shift helped move philosophy from logical atomism to ordinary language analysis.

3. Logical Positivism and Its Decline

- A.J. Ayer, Rudolf Carnap, and the Vienna Circle emphasized:

- Verificationism: a statement is meaningful only if it is empirically verifiable or logically necessary

- Rejected metaphysics, ethics, and religion as non-cognitive

- Verificationism: a statement is meaningful only if it is empirically verifiable or logically necessary

- Eventually critiqued for being too narrow, collapsing under its own criteria

4. Willard Van Orman Quine and Beyond

- Criticized the analytic/synthetic distinction

- Emphasized the holism of language and knowledge

- Helped shape naturalized epistemology—philosophy as continuous with science

III. Hermeneutics, Structuralism, and Post-Structuralism

1. Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900–2002): Truth and Dialogue

- In Truth and Method, argued that understanding is always interpretive and historical

- Truth arises through dialogue and the fusion of horizons

2. Structuralism

- Claude Lévi-Strauss applied linguistic structures to myth and culture

- Belief that underlying structures shape language, culture, and mind

3. Post-Structuralism and Deconstruction

• Michel Foucault (1926–1984):

- Analyzed the relationship between knowledge and power

- In Discipline and Punish and The History of Sexuality, showed how institutions shape the self

- Introduced “biopolitics”, surveillance, and discursive regimes

• Jacques Derrida (1930–2004):

- Developed deconstruction: meaning is never fixed; “there is no outside-text”

- Critiqued metaphysical binaries (presence/absence, speech/writing)

- Emphasized difference (différance) as the play of meaning

IV. Critical Theory and Liberation Philosophies

1. The Frankfurt School

- Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Herbert Marcuse, Jürgen Habermas

- Critiqued mass culture, instrumental reason, and technocratic domination

- Emphasized emancipatory reason, aesthetic experience, and communicative action

2. Feminist and Postcolonial Thought

- bell hooks, Iris Marion Young, Angela Davis, Gayatri Spivak questioned:

- Patriarchy and systemic inequality

- Eurocentrism and colonial epistemology

- The intersections of gender, race, class, and language

- Patriarchy and systemic inequality

V. Major Themes of 20th Century Philosophy

- Subjectivity and the limits of self-knowledge

- The fragmentation of meaning and truth

- The politics of identity, language, and power

- The collapse of grand narratives (Lyotard’s “incredulity toward metanarratives”)

- Efforts to reimagine ethics, freedom, and community

20th-century philosophy reflected the tragedies and aspirations of its time. It bore witness to both existential despair and the search for liberation in a fractured world.

Conclusion: Thinking After the End of Certainty

The 20th century taught philosophy to live without guarantees. Certainty was replaced by interrogation, unity by pluralism, and authority by dialogue. Amid war, technology, and systemic injustice, philosophers became not merely seekers of abstract truth but critics, healers, and interpreters of culture.

In the next chapter, we turn to the 21st century, where philosophy confronts the digital age, global crises, and the need for a renewed planetary ethic.

Chapter 12: East Meets West – Toward a Global Philosophy

Introduction