Revised 2025

Read The Solitaries: Inside Monastic Culture Part 1

Virgins and Philosophers: Early Proto-Monasticism

Inside Monastic Culture Series Part 2

Table of Contents

- Introduction – Before the Cloister, the Flame

- Roman Religious Colleges

- High Priests

- The Vestal Virgins

- Greek Philosophers

- Conclusion – From Sacred Orders to Monastic Origins

Introduction – Before the Cloister, the Flame

Long before stone cloisters echoed with whispered chants, and long before parchment carried the quiet labor of monks, the yearning for a higher life stirred in the ancient world.

In the shadows of temples and under the wide sky of the agora, men and women began to withdraw from the distractions of everyday power and pleasure—not into deserts or mountaintop caves, but into sacred houses, philosophical schools, and inner disciplines. They sought not only to worship or to learn, but to live a life shaped by purity, purpose, and something eternal.

This is the world of the proto-monastics: of Vestal Virgins, whose sacred flame burned at the heart of Rome; of Pythagoreans, who measured the cosmos with silence and number; of Cynics, who wandered the streets with empty bowls and scornful truths. Their houses were not monasteries in name—but in spirit, they anticipated what the monastic life would become.

This article explores those earliest seekers—virgins and philosophers—whose lives foreshadowed the great monastic traditions to come. It is a journey to the threshold of the cloister, where sacred fire and philosophical clarity first began to illuminate the path of renunciation and wisdom.

Roman Religious Colleges

Long before Christian monasteries emerged, ancient Rome developed institutions that resembled monastic life in surprising ways. Among the earliest were the Vestal Virgins, a group of priestesses established in the seventh century BCE.

They lived communally in the Atrium Vestae—the House of the Vestal Virgins—making it arguably the world’s first known proto-monastic residence. As members of the College of Pontiffs, the highest-ranking religious body in Rome, the Vestals played a key role in maintaining the sacred traditions of the Roman state.

To understand the Vestals, it’s essential to see them in the broader context of Rome’s official religious structure. Religious and social life in ancient Rome was deeply intertwined with legally recognized associations called collegia (Latin for “joined together”), which functioned as religious guilds, professional unions, or social clubs.

These groups mirrored the structure of the Roman Senate and operated with considerable influence—unless deemed politically or morally subversive, in which case they were banned. At various points, this included the Collegium Bacchus and even the early Christian Church.

Collegia existed for almost every trade and social function imaginable. There were colleges of actors, gladiators, gardeners, woodworkers, bakers, wine merchants, shoe makers, brothel keepers, and more. They served both practical and ceremonial roles, providing mutual support, funeral services, and shared rituals for their members.

At the top of the hierarchy were four major religious colleges:

- The Augurs, who interpreted the will of the gods through signs and omens.

- The Quindecimviri Sacris Faciundis, a board of fifteen priests who guarded sacred books and oversaw foreign cults.

- The Epulones, who organized public religious feasts and games.

- And most prestigious of all, the College of Pontiffs, which included the Vestal Virgins and supervised the entire state religion.

These colleges were dominated by the patrician elite—the wealthy ruling class—who used religious authority to reinforce their political power. Until the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE, these priestly bodies often served as influential advisory councils in Roman governance.

List of Ancient Roman Collegia

From the Via Labicana, circa 20 BCE, on display in the Capitoline Museum, Rome.

High Priests

In the highly structured world of Roman religion, the hierarchy of priests was visibly expressed even in the seating arrangements at sacrificial feasts. These priests—called sacerdotes—followed the strict order of the ordo sacerdotum, or priestly ranking system. Members of the College of Pontiffs occupied most of these seats, though the Vestal Virgins, despite their importance, were not part of this hierarchy.

At the symbolic head of the table—nearest to the gods—sat the Rex Sacrorum, or “King of Sacred Rites.” Following him were the three most prominent flamines maiores, or major priests:

- The Flamen Dialis, dedicated to Jupiter, king of the gods

- The Flamen Martialis, priest of Mars, god of war

- The Flamen Quirinalis, who served Quirinus—a deified version of Romulus, legendary founder of Rome

At the far end sat the Pontifex Maximus, the chief high priest and supreme authority in Roman religious affairs. Though seated farthest from the divine, his influence in the human world was unmatched.

Originally, Rome’s kings served as the city’s highest religious authorities. But after the monarchy was overthrown, this role was passed to the pontifices—a council of high priests led by the Pontifex Maximus. Their headquarters, the Regia (meaning “royal house”), was built along the Sacra Via, or “Sacred Road,” the main ceremonial street of ancient Rome. The Regia stood near the Roman Forum, forming a sacred triangle with the Temple of Vesta, the Temple of Caesar, and the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina.

In 12 BCE, Augustus Caesar assumed the title of Pontifex Maximus, and from that point on, it was held by the reigning emperor—blending religious and political power into a single office.

Roman religion had fifteen flamines (priests), each responsible for a specific deity and its cult. These were divided into two classes:

- The flamines maiores (major priests) served the most ancient and powerful gods of Rome’s Archaic Triad: Jupiter, Mars, and Quirinus. These posts were reserved for patricians.

- The flamines minores (lesser priests) served twelve minor deities such as Ceres and Vulcan. Unlike the major flamines, these roles could be held by plebeians (commoners).

Though the Rex Sacrorum held a title that echoed the kings of old, his role was mostly ceremonial. He was barred from military or political office, and his duties centered on conducting regular sacrifices and leading traditional rites in the Comitium—the public assembly space in the Forum.

His wife, the Regina Sacrorum (“Queen of Sacred Rites”), also held an important role. She performed monthly public sacrifices to the goddess Juno, adding a rare female presence to the male-dominated priesthoods of Rome.

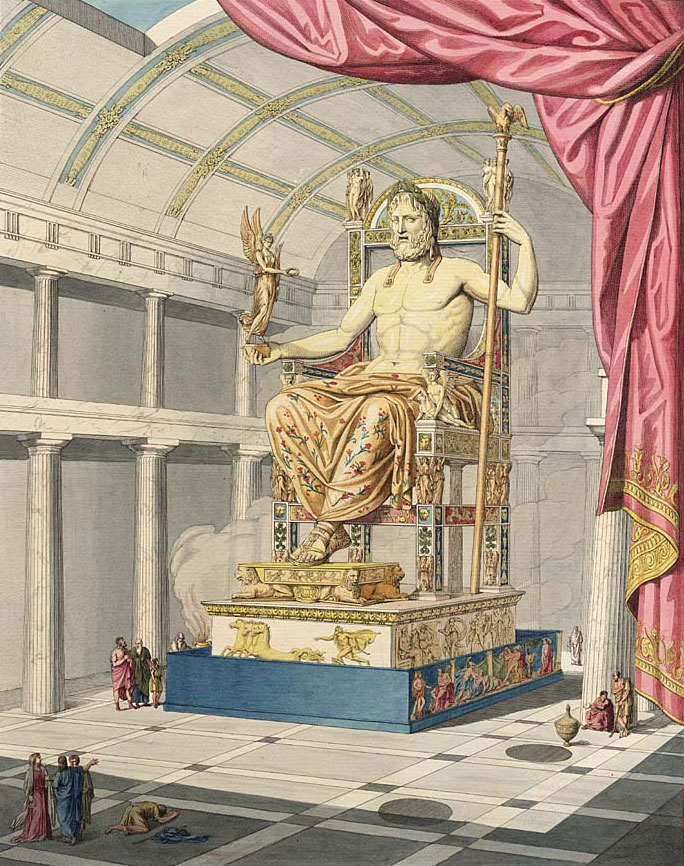

The Vestal Virgins

The Vestal Virgins were among the most revered religious figures in ancient Rome—and arguably the world’s first nuns. According to the Roman historians Livy and Plutarch, the order was established by King Numa Pompilius, Rome’s second king, who reigned from 717 to 673 BCE. These priestesses were dedicated to Vesta, the goddess of the hearth, and were charged with maintaining the sacred fire that symbolically protected the city. So long as the flame remained lit, Rome was believed to be safe.

The Vestals performed both public and private religious rites, safeguarded important state documents and wills of public figures, and served as living symbols of Roman virtue. Their white robes, modeled on those of Roman brides and matrons, emphasized purity and the sacred domestic order they embodied.

Membership in the order was limited to six girls at a time. Candidates were chosen by lot from among patrician families and had to be physically and mentally sound, with an unblemished reputation.

New Vestals were selected between the ages of six and ten and pledged thirty years of celibacy and service: ten years in training, ten in active duty, and ten as mentors to younger Vestals. After completing their service, they were often married off with honors and provided with a generous pension—an exceptional life path for women in ancient Rome.

The head of the order was the Virgo Vestalis Maxima, or Vestalium Maxima—the “greatest of the Vestals”—who also held a seat in the College of Pontiffs, the highest religious council in Rome.

Their home, the Atrium Vestae (House of the Vestal Virgins), was the first known proto-nunnery. It stood at the foot of the Palatine Hill, next to the Regia and the Temple of Vesta, in the heart of the Roman Forum.

The three-story palace was surrounded by a sacred grove and included over fifty rooms, a central atrium with twin pools, and statues of past Vestals and King Numa. It was a place of discipline, ceremony, and relative privilege, offering Roman women a unique space of power in an otherwise patriarchal society.

The order came to an end in 394 CE, when Emperor Theodosius I made Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire and banned pagan practices. The sacred flame was extinguished, the ancient rites discontinued, and the House of the Vestals was converted into a private residence—closing a remarkable chapter in religious history.

House of the Vestals Photos – Plan a Visit

Greek Philosophers: Lovers of Wisdom

The concept of a “lover of wisdom”—philosophos in Greek—was first associated with the ancient thinker Pythagoras in the sixth century BCE. Best known today for his contributions to mathematics, Pythagoras also founded one of the earliest philosophical communities. These early Pythagorean groups were not religious or monastic in the traditional sense, but they laid important groundwork for later communal and ascetic traditions.

Pythagorean communities were unusual for their time: they admitted both men and women, including Pythagoras’s own mother, wife, and daughter. His teachings blended mysticism, ethical discipline, and mathematics, which eventually led to the formation of two distinct schools:

- The Akousmatikoi (“Listeners”) followed the mystical and ceremonial aspects of his teachings. They emphasized secrecy, rituals, and a reverent lifestyle.

- The Mathēmatikoi (“Teachers”) focused on scientific inquiry, numbers, and logic—more closely resembling what we now think of as classical philosophy.

Both branches dissolved before the fifth century BCE. The mystical Akousmatikoi were gradually replaced by the more radical Cynics, while the rationalist Mathēmatikoi were absorbed into Plato’s Academy.

The Cynics, founded by Antisthenes (c. 445–365 BCE), a student of Socrates, and epitomized by Diogenes of Sinope (c. 404–323 BCE), carried forward the Pythagorean tradition of living simply—but with a sharper edge. They were mendicant philosophers, living in extreme poverty and practicing an austere lifestyle. They rejected conventional desires for wealth, status, and comfort, believing that true virtue came from living in harmony with nature and shedding material attachments.

Cynicism was deeply individualistic and often confrontational. Cynics were political radicals, dismissive of democracy and skeptical of egalitarian ideals, yet they advocated personal integrity, direct speech, and charitable action. Their goal was to provoke and awaken society, not to organize it.

Eventually, many of their core ideas—particularly their emphasis on self-discipline and inner freedom—were absorbed into Stoicism, a more structured and civic-minded philosophy suited to life in cities and empires. As a result, formal Cynic schools faded, though the movement experienced a modest revival in the early Roman Empire before vanishing entirely by the fifth century CE.

Yet the legacy of Cynicism, especially its ascetic lifestyle and public preaching, lived on. These ideals strongly influenced the development of Christian monasticism—where, as we’ll see, the followers of Jesus of Nazareth went on to form enduring spiritual communities of their own.

Conclusion: From Sacred Orders to Monastic Origins

Long before the emergence of formal monasteries, both the Roman and Greek worlds developed institutions that laid the foundation for communal, ascetic, and spiritually focused ways of life. In ancient Rome, the Vestal Virgins served as sacred guardians of the state religion—living communally under vows of chastity and discipline in what may be the earliest known nunnery. Their role was deeply embedded in the political and ceremonial fabric of the empire, blending the sacred with the civic.

Meanwhile in Greece, early philosophical communities such as those founded by Pythagoras, Antisthenes, and Diogenes offered alternative models of disciplined living. Though not religious in a formal sense, these groups practiced rigorous self-cultivation, communal living, and a rejection of worldly distractions—principles that would deeply influence later ascetic and monastic traditions. From the structured teachings of the Mathēmatikoi to the radical simplicity of the Cynics, these early seekers helped define the contours of a life devoted to something higher than the self.

Together, these ancient proto-monastic paths—Roman, Greek, civic, and philosophical—prepared the cultural ground for the rise of monasticism as a distinct and enduring institution. They reveal that the impulse to withdraw from the distractions of the world, to live with purpose, and to seek a higher truth is far older than any single religious tradition.

In the next article, we will turn to the birth of true monasticism: beginning with early Christian ascetics and the desert fathers, and tracing how small communities of prayer, solitude, and discipline evolved into the great monastic orders that would shape world religions for centuries to come.