Table of Contents

Introduction

What Holds Us Together

Part I. The Roots of Community

- Biological and Evolutionary Foundations

Cooperation, empathy, and the origins of belonging - Anthropological Origins — From Tribe to Civilization

How early societies turned survival into culture

Part II. Types and Scales of Community

- The Local and the Global

From neighborhood to planet: the expanding circle of belonging - Functional Communities — Political, Religious, Economic, and Digital Systems of Belonging

The intersecting networks that form the structure of society

Part III. Dynamics and Psychology of Belonging

- How Communities Form, Flourish, and Fail

The science of trust, communication, and renewal - The Individual and the Collective

Balancing freedom and fellowship in human society

Part IV. Building and Sustaining Communities

- The Science of Community Development

Participation, education, and the conscious design of belonging - The Ethics and Aesthetics of Belonging

Justice, beauty, and the moral imagination of community

Part V. The Future of Community

- The Global Village and Beyond

Toward planetary consciousness and civic cooperation - The Integrated Humanist Community

The next stage of civilization: reason, compassion, and unity

Introduction: What Holds Us Together

Community is the invisible architecture of human life.

Long before there were nations, cities, or religions, there was the circle—the small ring of faces gathered around a fire, sharing warmth, food, and stories. In that circle lay the origins of language, empathy, and civilization itself. The instinct to gather, to belong, to make meaning together is older than reason and deeper than law. It is the thread that connects the first villages to the global networks of today.

The word community descends from the Latin communitas, meaning “shared spirit” or “togetherness.” It implies something more than mere proximity; it suggests a union of purpose and feeling. In its truest form, community is not just about where we live, but how we live—with one another. It is the science of interdependence: the dynamic, evolving system through which individuals cooperate, compete, and co-create the conditions of their collective life.

In biology, a community is a web of species whose fates intertwine through the exchange of energy and matter. In sociology, it is a network of people connected by shared norms, trust, and identity. In philosophy, it is the ethical question of we: how should we live together? These perspectives converge on one truth—that all forms of community, from an ant colony to a democratic nation, are expressions of an ancient natural principle: life organizes itself through relationship.

And yet, the modern age is marked by a paradox. We are more connected than any generation in history, and yet we suffer unprecedented loneliness. The digital web has shrunk the planet but fragmented our attention. The idea of “community” has become both overused and under-lived: invoked in marketing campaigns, yet missing from many neighborhoods and hearts. We scroll endlessly through virtual networks, longing for real ones.

To understand the crisis of belonging that defines our century, we must return to first principles—not only to what community is, but to why it exists. The science of community seeks to uncover the biological, psychological, and cultural laws that govern how human groups form, flourish, and fail. It asks how social cohesion arises from individual minds, how trust can be measured, and how collective intelligence can evolve beyond the sum of its parts.

The Science Abbey approaches this inquiry through an Integrated Humanist lens. We see community as both a fact of nature and an art of the spirit. A healthy community is not a crowd, but a living organism—one that grows through communication, empathy, and shared purpose. It requires science to understand its structure and ethics to guide its soul. It begins in the village and culminates in the vision of a planetary society: a civilization aware of its interdependence with all life on Earth.

In what follows, we will trace the evolution of community from its biological roots to its digital frontiers. We will study how it binds and divides, how it empowers and deceives, how it mirrors the human psyche itself. And we will ask a final question—the one that may define the future of our species:

Can humanity build a community vast enough to include the world, yet intimate enough to feel like home?

Part I. The Roots of Community

1. Biological and Evolutionary Foundations

Before community was a human idea, it was a biological reality. Life itself began as cooperation—cells joining in mutual survival, forming colonies, tissues, and eventually complex organisms. Long before human societies, the principle of community shaped the natural world. It is written into the genetic code of existence: to live, life must relate.

The Origins of Cooperation

Evolution is not merely a struggle for dominance; it is also a story of alliance. The symbiotic partnership between cells gave rise to the first eukaryotes. Coral reefs, beehives, wolf packs, and rainforests—all are living examples of cooperative systems sustained by communication, reciprocity, and specialization. Nature thrives through balance between competition and collaboration; survival is rarely a solo act.

In humans, this instinct deepened into culture. The evolutionary biologists Peter Kropotkin and E. O. Wilson both observed that cooperation, not aggression, is the more enduring engine of survival. Our ancestors who shared food, defended one another, and raised children collectively passed on the genes of empathy. In evolutionary terms, kindness was adaptive. The village was not just a social convenience—it was the biological cradle of our species.

The Brain and the Bond

Neuroscience confirms what our ancestors practiced intuitively: community is wired into the brain. Mirror neurons allow us to feel what others feel. Oxytocin and dopamine reward trust, generosity, and shared ritual. Our nervous systems synchronize during group music, prayer, or laughter. Even the heartbeat adjusts to collective rhythm—an ancient echo of the campfire circle.

Modern studies in social neuroscience reveal that isolation activates the same pain centers as physical injury. Loneliness, therefore, is not simply emotional distress but biological alarm: the body signaling the danger of disconnection. We are creatures built for belonging.

From Kinship to Culture

For early humans, community began with kin—family groups bound by blood. But as tribes grew and intermarried, a new form of belonging emerged: symbolic kinship. Language, ritual, and myth became the connective tissue of larger groups. Shared stories and customs transformed genetic ties into cultural bonds. Fire, feast, and song became technologies of trust.

This expansion of social networks enabled cooperation among strangers, allowing for trade, agriculture, and the birth of civilization. Each new layer of social complexity—clans, tribes, villages, nations—extended the reach of empathy and identity, but also tested their limits. The same instincts that held people together could turn against outsiders. Every “we” implied a “they.”

Community as Evolutionary Intelligence

Seen from the lens of science, community is a higher-order intelligence system. Like neurons forming a brain, individuals form societies that process information, adapt, and self-organize. Communication—verbal or chemical—is the lifeblood of this collective intelligence. Communities learn, evolve, and transmit knowledge across generations, ensuring cultural continuity long after individuals perish.

When we study the rise of human civilization through this evolutionary lens, community appears not as an optional social form, but as the central mechanism of survival. The human being is the universe’s experiment in conscious cooperation. Each of us is both cell and system: a self within a greater self.

2. Anthropological Origins — From Tribe to Civilization

Community, as lived by early humanity, was neither abstract nor optional. It was immediate, tangible, and often the difference between life and death. The anthropological story of community is the story of human beings learning to survive together not merely by instinct, but by imagination.

The First Circles

Archaeologists studying Paleolithic sites find more than tools and bones—they find evidence of cooperation. Fire pits shared by many hands, coordinated hunts, burial sites that suggest collective ritual. These remnants show that humans did not just inhabit the same spaces; they inhabited one another’s lives. In the rhythm of shared labor, song, and ceremony, they forged bonds that became as binding as blood.

The earliest communities were built around kinship, geography, and necessity. Food, protection, and reproduction drew people together, but over time, language and meaning transformed survival into society. Speech allowed planning; myth gave purpose; memory created identity. A tribe was not merely a group—it was a living narrative.

Ritual and the Birth of Culture

Ritual became the architecture of early community. Around fires and altars, human beings enacted their unity through dance, drumming, and symbolic exchange. Each rite was a rehearsal of belonging. To participate was to affirm one’s place in the world.

Anthropologist Victor Turner called this state communitas—a sacred moment of shared equality and purpose that transcended ordinary social roles. In festivals, initiations, and communal gatherings, people entered into a direct experience of unity that reminded them why they lived together at all. Even today, the echo of communitas can be felt at concerts, protests, and moments of collective mourning or celebration. It is the pulse of the human spirit remembering itself.

From Village to City

As agriculture took root, the shape of community changed. The move from nomadic bands to settled villages transformed human relationships. Land became a shared inheritance; surplus demanded systems of storage, trade, and governance. Temples arose beside granaries. Writing evolved to record debts, laws, and stories. The first cities—Uruk, Mohenjo-Daro, Thebes, Xi’an—were not just economic hubs but centers of meaning.

Civilization was, in essence, the scaling up of community. But with scale came hierarchy and inequality. The organic reciprocity of the small group gave way to stratified systems of power. Kings replaced councils, priests interpreted the will of the gods, and armies enforced order. The warmth of the tribal hearth expanded into the grandeur of empires—and the distance between ruler and ruled widened.

Community and the Commons

Despite the rise of centralized authority, the spirit of shared life endured in the commons—the village well, the market square, the festival, the cooperative field. These spaces embodied the social contract: resources held in trust for the benefit of all. When commons thrived, societies flourished; when they were enclosed or exploited, social fabric frayed.

Anthropologist Elinor Ostrom would later demonstrate that self-governing communities often manage shared resources more sustainably than external authorities. Her research confirmed what ancient villages already knew: cooperation is not naïve—it is intelligent.

The Expansion of “We”

From kin groups to kingdoms, from city-states to nations, the meaning of “community” expanded with each stage of civilization. The question that guided this evolution was constant: How far can empathy stretch before it snaps?

Religion, trade, and philosophy each attempted to widen the circle. The Stoics spoke of cosmopolis—the city of humankind. Buddhism envisioned sangha as a universal fellowship. The Enlightenment imagined a “republic of reason” linking all rational beings.

Anthropology shows that community is not static; it is a living experiment in inclusion. Across millennia, humanity has struggled to balance intimacy and scale—to preserve the depth of belonging while embracing the breadth of diversity.

The Lesson of Origins

What began as the need to share food became the capacity to share meaning. The first hunters around a fire and the citizens of a global city are separated by epochs, but joined by the same invisible thread: the will to belong, and to make life together more than the sum of its parts.

Community, in this view, is not a relic of the past—it is the prototype of the future.

Every civilization begins with the circle. The question for ours is whether that circle can now include the whole Earth.

Part II. Types and Scales of Community

3. The Local and the Global

A community begins with proximity, but it does not end there. The place we share—our home, our street, our town—shapes the way we see the world. Yet, as human networks expand, the meaning of community stretches beyond geography into shared values, causes, and consciousness. From local neighborhoods to global alliances, humanity now lives across overlapping circles of belonging: the personal, the civic, the planetary.

The Local Community: Geography of the Heart

A local community is the oldest and most tangible form of human association. It is where daily life unfolds—where we meet the eyes of neighbors, hear the same church bells or call to prayer, and walk the same familiar roads.

Here, place is not merely physical but emotional. The historian Yi-Fu Tuan called this “topophilia”—the love of place. It explains why cities develop distinct cultures, dialects, cuisines, and senses of humor. Geography shapes character, and character, in turn, shapes community.

In the village, empathy arises through familiarity. In the city, it must adapt to diversity. The modern metropolis, with its anonymity and scale, often challenges the sense of belonging that smaller communities once provided. Yet even in vast urban centers, sub-communities emerge organically—through local markets, schools, shared interests, and civic spaces. The café, the park, and the library become secular temples of connection.

Healthy local communities share certain measurable traits: trust, reciprocity, participation, and communication. Sociologist Robert Putnam’s famous phrase “social capital” describes this invisible currency of cooperation. When neighbors know one another’s names, when people feel heard in town meetings, when streets are safe because citizens care—these are signs of a living social fabric. When they vanish, decline soon follows.

The National and International Community

As societies evolved, the sense of “we” expanded from the local to the national. Nations, though imagined rather than face-to-face, became vast moral communities linked by shared language, history, and identity. Benedict Anderson described them as “imagined communities”—real in their emotional power, yet sustained by symbols, myths, and collective memory rather than personal acquaintance.

At their best, nations unite people across regions and classes, binding millions in a project of common destiny. At their worst, nationalism divides the human species into rivals. The national community has therefore always carried a paradox: it generates solidarity within its borders but suspicion beyond them.

Beyond the nation lies the concept of the international community—the web of nations bound by treaties, global organizations, and moral consensus. This idea gained force after two world wars and the founding of the United Nations, when humanity began to see itself not merely as citizens of states, but as stewards of a shared planet. Climate agreements, human rights declarations, and scientific collaborations are all expressions of a slowly awakening global consciousness—a new, fragile layer of human community.

The Virtual Community

In the digital age, geography is no longer destiny. Communities now form in virtual spaces, transcending borders and time zones. A gamer in Tokyo and an activist in Nairobi can share goals, laughter, and creative work in real time. The Internet, at its most ideal, promised a new kind of community—open, decentralized, democratic.

And yet, virtual communities also magnify the challenges of belonging. Without physical presence or shared risk, trust becomes harder to build and easier to betray. Digital tribes can form around misinformation as easily as around truth. The same algorithms that connect also isolate, enclosing users in echo chambers that mimic community but lack its depth.

The task ahead is not to reject virtual life, but to humanize it—to restore empathy, accountability, and shared purpose to our online interactions.

The Global Village

The phrase “global village,” coined by media theorist Marshall McLuhan, predicted the current fusion of technology and culture. Our species now shares one planetary nervous system, instantly aware of events across continents. Natural disasters, social movements, and scientific discoveries ripple across humanity within seconds.

We have achieved global connection—but not yet global community.

To make the global village real, humanity must evolve from passive connectivity to active cooperation. This requires new forms of civic education, ethics, and planetary governance—a shift from competition to collective stewardship. In ecological terms, Earth itself is our ultimate community: a biosphere of interdependence in which the health of one part affects the whole.

Toward a Planetary Sense of Place

It is a strange truth of modern life that we can feel both rooted and rootless—attached to our hometown and adrift in the vastness of the world. But perhaps this tension is itself the growing pain of evolution.

For the first time in history, the circle of belonging has the potential to encompass all of humanity and the living Earth. The task before us is to cultivate a planetary sense of place: to feel at home not only in our neighborhood, but in our species.

In this way, the local and the global cease to be opposites. They become reflections of one another—nested rings of community that extend from the doorstep to the stars.

4. Functional Communities — Political, Religious, Economic, and Digital Systems of Belonging

Human beings do not live in a single community but in many overlapping ones. Each fulfills a distinct function: to govern, to worship, to create, to trade, to defend, to learn, to play. The pattern of civilization is woven from these intersecting circles—each with its own laws, rituals, and language of belonging. Together, they form the living mosaic of society.

Political and Civic Communities: The Architecture of Cooperation

Politics is, in essence, the management of community at scale. It transforms the primal need for coordination into the organized system of governance. From the Athenian polis to modern democracies, political communities exist to translate the will and welfare of many into a common direction.

At the smallest level, civic communities thrive where citizens feel ownership. Town councils, volunteer groups, local boards, and public forums embody democracy in miniature. Participation, rather than policy alone, gives civic life its vitality.

When citizens withdraw, community weakens; when they engage, the system renews itself.

At national and international levels, the same principle expands outward. The idea of the “body politic” implies that a society, like a living organism, functions through the cooperation of its parts. Justice is its immune system, communication its nervous system, education its circulatory system. The challenge is to sustain coherence without uniformity—to build a civic order capable of managing diversity without erasing it.

Integrated Humanism envisions the scientific study of governance not as cold technocracy but as civic ecology—the understanding that good government grows from the health of its communities.

Religious and Spiritual Communities: The Communion of Meaning

Where political communities organize behavior, spiritual communities organize consciousness. They address humanity’s most enduring questions: Who are we? Why are we here? What is good? From ancient temples to modern sanghas and churches, these communities cultivate shared myths, rituals, and moral frameworks that orient human life toward transcendence and service.

Religion, at its best, offers a structure for belonging that extends beyond blood and nation. It binds through shared practice rather than lineage, creating fellowship among strangers. At its worst, it can become a wall instead of a bridge—a system of exclusion rather than connection. The measure of any spiritual community lies in whether it deepens compassion or hardens identity.

In an age of pluralism, the global challenge is not to erase religions, but to evolve them—to discover the universal ethics that underlie them all. The Science Abbey vision regards this as the work of Scientific Humanist spirituality: a community of inquiry grounded in reason and reverence alike, seeking understanding without dogma and service without division.

Economic and Professional Communities: The Networks of Production

Where meaning drives the spiritual life, exchange drives the material. Economic communities form wherever people collaborate to create, trade, or sustain livelihoods. From ancient guilds to modern industries, from farmer cooperatives to open-source software networks, these communities transform individual skill into collective power.

The Industrial Revolution gave birth to new professional identities—engineers, factory workers, financiers—each forming its own tribe with codes, hierarchies, and ethics. Today’s knowledge economy multiplies these micro-communities: scientific fields, creative industries, and global corporations, all bound by shared language and practice rather than shared geography.

Yet the market alone cannot substitute for community. When economic identity eclipses civic or moral belonging, society risks becoming a marketplace without a soul. The growing field of social entrepreneurship and ethical business represents an effort to restore balance—where profit aligns with purpose, and work becomes a vehicle of human flourishing rather than alienation.

Intellectual and Artistic Communities: The Fellowship of Ideas

Ideas, like genes, evolve through exchange. From Plato’s Academy to modern universities, from salons to scientific journals, intellectual communities have driven humanity’s ascent. They thrive on curiosity, debate, and peer review—the disciplined conversation of the species with itself.

Artistic communities, meanwhile, translate collective experience into emotion and image. The guilds of the Renaissance, the literary circles of Paris, the avant-garde collectives of the twentieth century—all demonstrate how art can become the heartbeat of culture, revealing what societies feel before they can articulate it. When artists and thinkers collaborate, culture advances; when they are silenced or starved, community loses its capacity for reflection and renewal.

The Science Abbey itself stands as such a community of thought—a modern fellowship of science, art, and conscience—where knowledge and creativity are seen not as separate pursuits but as twin expressions of the same human longing to understand and to uplift.

Digital and Virtual Communities: The New Commons

The Internet has redefined community more radically than any invention since the printing press. Virtual spaces now host vast societies of conversation, collaboration, and identity. Wikipedia, open-source projects, online support groups, and creative networks demonstrate the immense potential of digital cooperation. Yet social media also reveals the dangers of unmoored belonging—tribalism without accountability, outrage without empathy, connection without communion.

Digital community is still in its infancy, its ethics unformed. The next stage of civilization will depend on whether humanity can transform its online networks into genuine commons: spaces of dialogue, learning, and empathy rather than division and noise. The principles of clarity, integrity, and humanity—the NAVI triad—are as essential in virtual life as in physical society.

Interdependence of Systems

No community exists in isolation. The political depends on the economic; the spiritual depends on the civic; the digital reflects the psychological. Like ecosystems, these systems of belonging overlap and evolve together. When one sickens, all are affected. To study the science of community is to study the ecology of civilization itself.

The human task, then, is not to choose among these communities, but to harmonize them—to weave a coherent life from the many circles to which we belong. Only then can humanity advance from fragmented functions to a living, integrated whole.

Part III. Dynamics and Psychology of Belonging

5. How Communities Form, Flourish, and Fail

The Birth of Belonging

Community is both an art and a science. It forms wherever individuals align around shared values, needs, or goals. Yet the mechanisms that sustain or destroy it are often invisible—operating in the subtleties of trust, communication, and identity. Understanding these forces is essential for building resilient societies in a world of rapid change.

At its simplest, a community begins with recognition. One person sees another as part of their circle of meaning—someone to cooperate with rather than compete against. Through repeated interaction, trust emerges; through shared action, identity forms. Over time, norms and rituals arise that stabilize expectations. What began as mutual benefit evolves into moral obligation: an unwritten agreement that “we belong to one another.”

The Science of Trust

Trust is the lifeblood of community. Without it, no contract, institution, or network can hold. Sociologists distinguish between “bonding” trust—ties among similar people—and “bridging” trust—ties across difference. Healthy communities balance both: they nurture intimacy within while maintaining openness without. When bonding dominates, a community may become insular or tribal. When bridging dominates without bonding, it may become abstract and rootless. Sustainability lies in the dynamic equilibrium between the two.

Trust is not an emotion but a measurable social resource. It can be built through transparency, fairness, and shared success, and destroyed through secrecy, corruption, or neglect. It accumulates slowly and evaporates suddenly. Every level of society—from families to governments—depends on its steady maintenance.

Communication and Connection

Communication is the structural glue of belonging. Words, symbols, and gestures allow individuals to align their perceptions of reality. Miscommunication or censorship weakens cohesion; honest dialogue strengthens it. In this sense, free speech is not merely a political right but a biological necessity for social systems that learn and adapt. A silent community stagnates; a speaking one evolves.

Language itself is a kind of social technology, evolving to sustain larger and more complex groups. Shared narratives and metaphors act as cultural software that coordinates behavior. When communication channels are open, diverse minds can converge on common goals. When they are closed, misunderstanding becomes inevitable.

Values and Moral Frameworks

Shared values and moral codes define the ethical boundaries of community. These are expressed in customs, taboos, and laws that guide behavior and mediate conflict. The anthropologist Mary Douglas observed that every community maintains its own notion of purity and danger—what is acceptable and what threatens its identity. The more coherent the moral framework, the stronger the community’s internal trust. But when that framework becomes rigid, it can suffocate diversity and innovation.

The vitality of a community depends on its moral adaptability. Healthy societies evolve their ethics as new knowledge emerges. The ability to question authority, reinterpret tradition, and include previously excluded voices is a sign not of moral decay, but of moral maturity.

Stability, Flexibility, and Renewal

Communities flourish when they achieve balance between stability and flexibility. Too much change leads to chaos; too little leads to stagnation. The most enduring groups—religious orders, scientific societies, long-lived cities—cultivate traditions while allowing periodic reform. Renewal rituals, elections, and open debate serve as evolutionary mechanisms that prevent decay. Decline often begins when leaders suppress dissent or when members lose faith in the system’s fairness.

Failure can take many forms. Communities collapse through conflict, corruption, inequality, or simple apathy. When individuals feel unseen or unheard, they disengage, and the social fabric frays. Polarization erodes empathy; excessive conformity erodes creativity. Some communities dissolve violently; others fade quietly into indifference. In both cases, the cause is the same: the loss of trust and shared meaning.

The Ecology of Belonging

The science of belonging mirrors the laws of ecology. Diversity strengthens resilience; communication enables adaptation; mutual aid sustains life. Communities that honor these principles endure, even through crisis. Those that deny them, however powerful they appear, eventually fragment.

The task of the modern age is to study and apply these principles consciously. In an era of global interdependence and digital disconnection, we must learn again how to form human circles of trust—local, civic, and planetary—that can thrive amid complexity. Only then can community evolve from instinct into intelligence, from survival strategy into shared wisdom.

Part III. Dynamics and Psychology of Belonging

6. The Individual and the Collective

The Paradox of Self and Society

Every community begins with individuals, yet no individual exists apart from community. Human identity forms through relationship: we discover who we are by seeing ourselves reflected in others. This interdependence creates the central paradox of social life—how to balance autonomy and belonging. Too much individualism dissolves cohesion; too much conformity erases freedom. Civilization depends on the artful negotiation between the two.

The philosopher Aristotle called humans zoon politikon—political animals—because the full development of our nature occurs only in community. But the Enlightenment reasserted the primacy of the individual, defining rights and freedoms as protections against collective power. Modern society oscillates between these poles: the call to self-expression and the need for solidarity. A mature community honors both—it safeguards personal conscience while nurturing shared purpose.

Roles, Leadership, and Responsibility

Within every group, roles emerge to organize action and meaning. Some lead, others follow, but leadership in its healthiest form is service rather than domination. Communities thrive when leadership circulates according to competence, character, and context rather than hierarchy alone. The anthropologist Margaret Mead observed that small societies sustain equality by rotating authority and encouraging communal participation. The same principle applies to modern institutions: authority must remain accountable to the group that grants it.

Followers also bear responsibility. A community of passive dependence weakens itself. Healthy membership means active engagement—questioning, contributing, and caring for the whole. Leadership and followership, properly understood, are two expressions of the same moral duty: to serve the common good.

The Psychology of Group Identity

Belonging satisfies one of the deepest psychological needs. It provides safety, recognition, and purpose. Yet it also creates boundaries—distinctions between “us” and “them.” Social identity theory explains how individuals derive self-esteem from group membership, often leading to favoritism toward the in-group and bias against outsiders. This mechanism once ensured survival but now fuels many of the world’s divisions.

Communities must therefore cultivate conscious inclusion. The more secure people feel in their identity, the more open they can be to difference. Rituals of hospitality, public dialogue, and shared projects reduce psychological distance. The Integrated Humanist approach emphasizes empathy as the bridge between individual identity and collective awareness—a practice of seeing the self in others without erasing difference.

Conformity, Creativity, and Dissent

Social belonging exerts powerful pressure to conform. In moderation, conformity fosters harmony; in excess, it suppresses truth. Every great reform or discovery began as dissent. Societies that honor creative independence renew themselves through innovation. Those that punish dissent stagnate.

The challenge is not to eliminate conflict but to elevate it—to channel disagreement into dialogue. Science, democracy, and art all depend on this principle. Constructive dissent keeps communities honest. When individuals feel safe to voice minority views, collective intelligence expands. Freedom of thought is therefore not a privilege but an ecological requirement for any adaptive society.

Empathy and the Ethics of Relation

At the emotional core of community lies empathy—the capacity to understand and share another’s experience. Neuroscience shows that empathy arises from mirror neuron systems that link perception and emotion. Ethics transforms that biological impulse into conscious choice: compassion as practiced intelligence. The health of a community can often be measured by its empathy—by how it treats the vulnerable, the dissenting, and the unseen.

Empathy must be balanced by integrity. Unchecked emotional contagion can distort judgment, while detached rationality can dehumanize. The Integrated Humanist perspective seeks their synthesis: clear reason guided by compassionate awareness. Through this balance, individuals mature, and communities evolve toward wisdom.

Integration and Wholeness

The individual and the collective are not opposites but two halves of a single process. The individual is the cell; the community, the organism. When the cell thrives, the body flourishes; when the body is healthy, the cell finds purpose within it. The mature society recognizes this reciprocity and designs its systems—education, governance, economy—to support both personal development and collective well-being.

In this view, community becomes the arena of self-realization. We learn who we are through the responsibilities we assume and the contributions we make. To live well together is to become fully human. The science of community thus becomes the science of the self writ large: the study of how consciousness, multiplied and connected, learns to care for its own reflection in others.

Part IV. Building and Sustaining Communities

7. The Science of Community Development

From Spontaneity to Design

Communities often begin spontaneously—through geography, kinship, or shared interest—but their long-term success depends on conscious cultivation. Community development is the science and art of guiding that process. It studies how people organize, cooperate, and create systems that meet collective needs while respecting individual freedom. In its modern form, it combines sociology, economics, education, and design thinking with ethics and empathy.

Traditional societies sustained community through custom and continuity; modern societies must sustain it through knowledge and participation. Industrialization, urban migration, and digital life have dissolved many of the natural bonds that once held groups together. Rebuilding connection now requires intentional effort—planning that is both structural and spiritual. The goal is not merely growth, but belonging.

Principles of Sustainable Development

Strong communities emerge from four foundational principles: participation, inclusion, transparency, and adaptability. Participation ensures that members have agency in shaping their shared life. Inclusion guarantees that diversity becomes a source of strength rather than division. Transparency builds trust by making decision-making visible. Adaptability allows a community to respond creatively to change.

Development guided by these principles resists both authoritarian control and passive dependency. It empowers people to act as co-creators of their environment. Urban planners, educators, and social scientists increasingly view communities as living systems—networks of relationships that require feedback, renewal, and care. Whether the context is a rural village or a virtual network, the pattern is the same: a community flourishes when people feel both responsible for and supported by one another.

The Role of Education and Knowledge

Education is the most reliable catalyst of community growth. It transmits values, skills, and shared narratives that allow individuals to contribute meaningfully. Schools, libraries, and universities function as social infrastructure, forming the intellectual commons where dialogue replaces dogma. Community-based learning—citizen science, adult education, local workshops—extends this mission beyond formal institutions. Knowledge empowers participation; ignorance isolates.

Integrated Humanism regards education not only as a means to employment or progress but as an act of social stewardship. To teach is to weave the social fabric; to learn is to join it. The Global Civic Curriculum and similar initiatives represent this new frontier of education—where the classroom becomes a training ground for democracy and global citizenship.

Technology and the New Commons

Digital tools have transformed the landscape of community development. Online platforms enable crowdfunding, civic mapping, local problem-solving, and global collaboration. Open-data initiatives let citizens track budgets, environmental indicators, or neighborhood safety. Social networks can amplify cooperation as easily as they can amplify division. The difference lies in design and intent.

The challenge is to use technology to enhance human connection rather than replace it. A healthy digital commons functions like a public square—open, respectful, and governed by shared norms. Ethical design, data literacy, and civic moderation are the new cornerstones of modern community development. When aligned with transparency and empathy, technology can help reweave the social fabric that industrial modernity once frayed.

Case Studies in Cooperation

Examples of community development appear in every culture and era. The cooperative movements of 19th-century Europe, the kibbutzim of Israel, the community land trusts of the United States, and the participatory budgeting experiments of Latin America each demonstrate different approaches to shared governance and resource management. In the 21st century, sustainable eco-villages and urban regeneration projects apply similar principles with environmental awareness.

In all cases, the pattern repeats: when people share responsibility, they generate resilience. When outsiders impose systems without participation, failure follows. The principle of subsidiarity—solving problems at the most local effective level—remains one of the surest foundations for civic health.

Science, Art, and the Human Spirit

The science of community development studies measurable outcomes—income, education, health, and engagement—but it also depends on an immeasurable element: spirit. Festivals, art, and shared rituals bind people through joy as much as necessity. Music, design, and storytelling make belonging visible. A city with murals, gardens, and public art projects radiates connection; one stripped of culture becomes a machine of isolation.

Development, therefore, must serve both body and soul. The aim is not merely to build housing, roads, or digital platforms, but to build meaning. The most advanced societies will be those that combine scientific planning with aesthetic sensitivity and moral imagination—a harmony of structure and spirit.

Toward Conscious Community Building

To build community is to participate in evolution itself. It is the deliberate continuation of the same cooperative process that shaped life from the first cell. The science of community development teaches us that progress is not measured by growth alone, but by the depth of relationship and the quality of shared life.

The next phase of civilization will depend on communities capable of self-organization, empathy, and continuous learning. These will be the laboratories of the future—living systems where reason and compassion meet in practice. Every neighborhood, every network, every circle of friends has the potential to become such a site of transformation: a small, luminous example of humanity learning how to live together wisely.

Part IV. Building and Sustaining Communities

8. The Ethics and Aesthetics of Belonging

The Moral Dimension of Community

A community is more than a collection of people; it is a living expression of shared ethics. Its strength depends not only on the efficiency of its institutions but on the moral imagination of its members. Ethics defines the “why” of community—the sense of purpose that makes belonging meaningful. Without ethical coherence, even the most advanced society becomes an empty shell of rules without spirit.

At the heart of ethical community lies the principle of mutual respect. Each person is recognized as both contributor and beneficiary of the common good. Justice and fairness sustain trust, while compassion transforms cooperation into kinship. From ancient villages to modern democracies, communities endure when they embody this equilibrium—balancing responsibility with care, rights with duties, liberty with empathy.

The Integrated Humanist view understands ethics not as abstract philosophy but as lived practice. Morality is enacted in daily life—in how we listen, forgive, share, and protect. Every interaction, no matter how small, contributes to the moral climate of the whole.

The Beauty of the Social World

Where ethics governs behavior, aesthetics shapes perception. The physical and emotional beauty of a community influences how its members feel and act. Architecture, nature, music, and ritual all affect the sense of harmony or alienation within a place. A neighborhood lined with trees invites cooperation; one stripped of color and silence breeds detachment. Beauty is not a luxury—it is a social necessity.

Throughout history, great civilizations have expressed their communal values through art and design. Greek agoras, Daoist and Confucian courtyards, Gothic cathedrals, and Japanese gardens each reflect the idea that beauty can teach virtue. Modern urban planners increasingly recognize that aesthetics are not peripheral to social health: walkable streets, public parks, and shared creative spaces correlate strongly with civic engagement and mental well-being.

Aesthetic belonging also extends beyond the visual. The rhythm of community life—the sound of languages, bells, laughter, and birdsong—constitutes its living music. When a community is healthy, its atmosphere feels alive. When it decays, silence or noise replaces melody. The task of civic design is therefore not only to build structures, but to compose harmony.

Inclusion and Human Dignity

Ethical and aesthetic integrity both depend on inclusion. A beautiful city that excludes the poor or discriminates against minorities is ethically hollow. Likewise, a tolerant community that neglects its environment is spiritually incomplete. True belonging must extend to all—across class, race, gender, ability, and belief. Diversity is not a problem to be managed but a reality to be embraced.

Social science confirms that inclusive communities are more innovative, stable, and prosperous. But beyond data lies a deeper truth: inclusion is an expression of human dignity. Every person has something to contribute, and the recognition of that potential is the foundation of moral order. The human right to belong is therefore the cornerstone of any ethical civilization.

Justice, Stewardship, and the Common Good

The health of community can be measured by how it treats the least powerful. Justice—economic, social, and ecological—is the maintenance of right relationship among people and between people and planet. Stewardship extends that principle to future generations, reminding us that the community of today is the inheritance of tomorrow.

In practical terms, justice requires transparent governance, equitable access to opportunity, and protection from exploitation. But it also requires empathy in power—the willingness of leaders to serve rather than dominate. A just community is not one without conflict, but one that resolves conflict through fairness and compassion.

Ethical stewardship further demands environmental awareness. A society that destroys its land and water cannot sustain its people. Ecology and ethics converge in the recognition that care for the Earth is care for ourselves.

The Aesthetics of Relationship

The beauty of belonging is not found only in art or architecture, but in the texture of human interaction. Courtesy, attentiveness, humor, and generosity are aesthetic acts—forms of grace that elevate everyday life. When people relate with dignity, the atmosphere of the community changes. Harmony becomes palpable.

Anthropologists often note that ritualized politeness and hospitality are universal social arts. They transform survival into civilization. To greet a stranger kindly, to share a meal, to listen without interruption—these gestures are the choreography of moral beauty. Their absence signals decline not only of manners, but of meaning.

Toward a Culture of Wholeness

The future of community depends on the fusion of ethics and aesthetics—a culture of wholeness where moral purpose and sensory harmony reinforce one another. Such a society would measure progress not only by wealth or technology, but by beauty, justice, and kindness.

Integrated Humanism envisions this synthesis as the next stage of civilization. A city, an organization, or a digital platform designed with both compassion and elegance becomes more than a structure; it becomes a sanctuary of the human spirit. When science and art unite under the guidance of conscience, community becomes not merely sustainable, but luminous.

The work of building such communities begins where we stand: in our conversations, our neighborhoods, and our shared imagination. Belonging is both a gift and a responsibility—one that, if cultivated wisely, can transform the human condition from coexistence to communion.

Part V. The Future of Community

9. The Global Village and Beyond

The Age of Connection

Humanity now lives in an era of unprecedented interconnection. Communications networks link nearly every inhabited region of the Earth; trade, travel, and technology have woven humanity into a single planetary system. The phrase “global village,” coined by Marshall McLuhan in the 1960s, foresaw this transformation. It described a world where distance collapses and the affairs of one part of the planet become the concern of all.

Yet connection does not guarantee communion. The global village is real in infrastructure but incomplete in spirit. We share information faster than ever, but we do not yet share understanding. The challenge of the twenty-first century is to convert connectivity into solidarity—to cultivate a sense of planetary belonging that matches our technological reach.

Globalization and Fragmentation

Globalization has created vast exchanges of goods, ideas, and cultures, lifting millions from poverty and fostering scientific cooperation. But it has also disrupted traditional ways of life, widened economic inequality, and intensified competition for identity. Many communities feel diminished or displaced by the same forces that connect them. The digital world, once expected to unite humanity, has instead revealed its divisions in high resolution.

Sociologists describe this duality as “glocalization”—the simultaneous pull toward global integration and local differentiation. A healthy future will require reconciling these forces. Communities must learn to remain rooted while reaching outward—to preserve their heritage without rejecting the shared destiny of the species.

The Rise of Planetary Awareness

Despite conflict and fragmentation, a new consciousness is emerging. Climate change, pandemics, and technological interdependence remind us that no nation stands alone. The biosphere itself functions as a single community of life, and humanity is its self-aware member. This recognition marks a profound shift in worldview: from competition for survival to cooperation for sustainability.

Movements for environmental stewardship, global health, and social justice are early expressions of this planetary awareness. International collaborations in science—such as climate research, space exploration, and vaccine development—demonstrate how shared knowledge can transcend borders. The future community will not be defined by territory, but by responsibility.

Technology and the Commons of Mind

Digital technology, for all its hazards, offers tools for the construction of global community. Platforms for open education, decentralized governance, and cross-cultural dialogue have begun to appear. Artificial intelligence and data science can map social needs, optimize resource distribution, and facilitate cooperative decision-making—if guided by ethics and transparency.

The danger lies in centralization and manipulation. A planetary community governed by algorithms alone would not be human; it would be mechanical order without moral compass. To build a true commons of mind, humanity must pair technological intelligence with ethical intelligence. The science of community must evolve into the science of conscience.

Global Citizenship and Civic Education

The concept of global citizenship provides the moral framework for this new era. It affirms that every person carries both rights and duties beyond national borders: to uphold human dignity, protect the Earth, and contribute to collective progress. Education is the primary vehicle of this consciousness. Schools and media must teach not only history and science but empathy and critical thinking—the skills that make cooperation possible.

The Global Civic Curriculum of Science Abbey represents one model of such education. It unites logic, ethics, science, and culture into a coherent foundation for planetary life. The goal is not to erase cultural diversity, but to give it a shared language of reason and respect. Through civic education, humanity can transform its diversity from friction into synergy.

Challenges of the Global Era

The path to global community will not be easy. Nationalism, economic inequality, and information warfare threaten collective trust. Climate refugees, digital surveillance, and resource scarcity test our moral capacity. The transition from a world of nations to a world of neighbors requires new institutions, new ethics, and new forms of leadership.

But history shows that crises often catalyze evolution. The same global pressures that endanger civilization also compel innovation. When human intelligence is guided by conscience, adversity becomes the engine of moral progress. The future community will not arise from utopian design, but from the patient accumulation of trust across cultures.

Beyond the Global Village

The next stage of human evolution may be called the planetary society—a civilization conscious of itself as one organism within a living Earth. Its citizens will not only exchange goods and data, but also meaning. Science will serve compassion; technology will serve transparency; and culture will serve wisdom. Such a community would be the culmination of millennia of social experiment—the flowering of the tribal circle into a global mandala.

To reach that state, humanity must outgrow the idea of “us” and “them.” The future will not be built by nations alone, but by networks of conscience—scientific, artistic, and humanitarian communities that transcend borders while honoring local roots. The measure of progress will be simple: not how much power we wield, but how well we care for one another and the planet we share.

The Evolution of Belonging

Community began as a means of survival. It has become the mirror of our collective soul. Each expansion of belonging—from family to tribe, from city to nation, from humanity to Earth—reflects a growing circle of empathy. The next leap is not merely technological but spiritual: to recognize that the universe itself is a communion of relationships, and that our role is to live in harmony within it.

The global village is not the end of history but the beginning of awareness. What lies beyond is the work of civilization itself: to turn connection into compassion, and compassion into wisdom.

Part V. The Future of Community

10. The Integrated Humanist Community

The Next Step in Human Evolution

Every age defines itself by how it understands community. The tribal era valued kinship; the agricultural era valued land; the industrial era valued production; the digital era values connection. The coming era—the Age of Intelligence—will value integration: the conscious harmonization of reason, empathy, and shared purpose.

The Integrated Humanist Community represents this next evolutionary stage. It is not confined to a nation, religion, or ideology, but arises wherever people unite around truth, compassion, and responsibility. It seeks to build a civilization that is rational without being cold, spiritual without being dogmatic, and communal without suppressing individuality. It is humanity’s experiment in mature cooperation.

Science and Spirit in Balance

Integrated Humanism begins from the scientific understanding that all life is interconnected. Physics, biology, and ecology converge on the same principle: nothing exists in isolation. Yet knowledge alone cannot sustain belonging. The human heart demands meaning, beauty, and moral orientation. The challenge is not to choose between science and spirit, but to reconcile them—to let evidence and empathy guide one another.

This balance transforms the idea of community into a conscious practice. Inquiry replaces ideology; compassion replaces coercion. A community that unites scientific literacy with moral imagination becomes capable of solving complex global problems while honoring human dignity. It turns reason into a form of love.

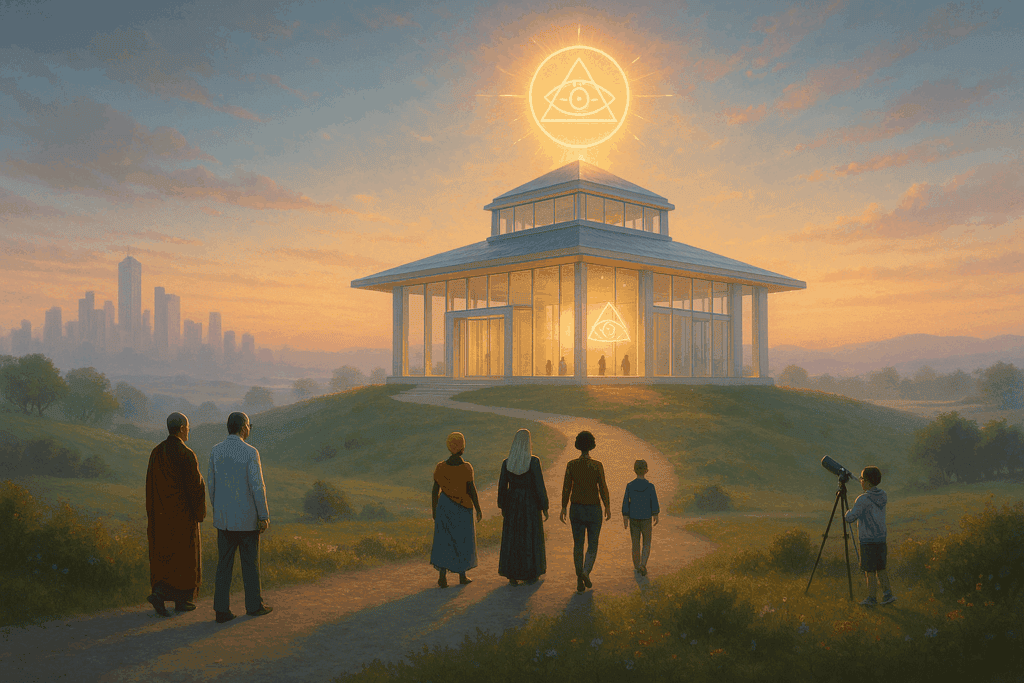

The Temple Without Walls

Science Abbey envisions the Integrated Humanist Community as a “monastery without walls”—a global fellowship of thinkers, creators, teachers, and citizens devoted to understanding and uplifting the human condition. Its work is secular yet sacred: the pursuit of truth through study, dialogue, and service.

Such a community need not share uniform belief; it shares a method—a disciplined way of thinking, feeling, and acting grounded in evidence and empathy. It values clarity over certainty, collaboration over competition, and wisdom over power. It is open to all who seek to learn and to contribute.

Through initiatives like the Global Civic Curriculum, the Neutral Analytical Vigilance Institute (NAVI), and the Human Maturity Initiative, this vision translates philosophy into action. Each program strengthens one dimension of belonging—education, intelligence, and personal development—within a coherent ethical framework.

The Ethics of Intelligent Belonging

In the Integrated Humanist model, belonging is redefined as an act of consciousness. To belong is not merely to be accepted by others, but to accept responsibility for the whole. Membership becomes a moral relationship, not a social label. The citizen of the future must learn to think globally, act locally, and feel universally.

This ethic calls for humility in knowledge and courage in compassion. It requires that we replace competition with collaboration, domination with dialogue, and prejudice with curiosity. Science and technology must serve human maturity, not the other way around. The community of the future will not be measured by its size or wealth, but by the depth of its understanding and the sincerity of its care.

A Global Fellowship of Purpose

The Integrated Humanist Community envisions a planetary network of individuals and organizations dedicated to learning, peace, and progress. It bridges cultures and disciplines: scientists with philosophers, artists with engineers, educators with citizens. Together they form a new civic order grounded in the unity of truth and goodness.

This fellowship will operate across physical and digital realms—laboratories, classrooms, sanctuaries, and online platforms—each a node in the same web of awareness. Its emblem is the circle: equal, inclusive, and luminous. Its method is dialogue; its currency is knowledge; its power is integrity.

Such a community does not replace nations, religions, or families—it renews them. It offers a framework through which all can coexist within a shared planetary ethic. It is not a utopia but a practice: the ongoing experiment of civilization learning to think and feel as one organism of consciousness.

From Civilization to Communion

The ultimate goal of community is not merely survival or organization, but communion—the realization that our separateness is an illusion sustained by fear and habit. When the boundaries of identity dissolve into empathy, and empathy matures into understanding, humanity approaches its next threshold: global wisdom.

The Integrated Humanist Community embodies this transition. It invites individuals to cultivate inner maturity while participating in collective transformation. It sees in every person the reflection of the whole and in the whole the expression of each person’s highest potential. To build such a society is to continue the great experiment of life itself: evolving from instinct to insight, from tribe to humanity, from humanity to harmony.

The Circle Returns

Community is the oldest human invention and the newest human frontier. It was born when the first people shared a fire, and it evolves still whenever strangers find common purpose across the expanse of the world. Its form changes—village, city, network, planet—but its essence remains the same: life becoming aware of its interdependence.

The Science of Community reminds us that belonging is not a social luxury; it is the structure of survival and the foundation of meaning. Every advance in civilization, from language to democracy to digital communication, has been an experiment in enlarging the circle of “we.” Today, that circle can finally encompass the Earth itself.

To participate in this evolution is to act consciously—to live as both individual and whole, as student and steward, as scientist and neighbor. Each time we build trust, share knowledge, or create beauty together, we renew the oldest law of life: that existence flourishes through relationship.

The future of humanity will not be decided by algorithms or borders, but by how deeply we learn to belong—to one another, to the planet, and to the truth we share. In that belonging lies not only our continuity, but our awakening.

The circle is unbroken. It widens still.

The Science Abbey Vision

The Science Abbey stands as both symbol and seed of this vision—a living experiment in the evolution of community. It gathers minds and hearts around the experience of enlightenment through knowledge, art, and service. It affirms that the destiny of civilization lies not in domination, but in understanding; not in conquest, but in communion.

The age of isolation is ending. A new civilization is dawning—scientific in method, humanist in purpose, spiritual in character. Its foundation is community; its medium is consciousness; its aim is wisdom.

The task before us is simple and immense: to build a world where reason and compassion coexist, where truth serves peace, and where belonging extends to all life.

This is the science of community.

Of course, it begins with us.

Bibliography

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Revised Edition. London: Verso, 2006.

Aristotle. Politics. Translated by Benjamin Jowett. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1885.

Bauman, Zygmunt. Community: Seeking Safety in an Insecure World. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2001.

Douglas, Mary. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge, 1966.

Durkheim, Émile. The Division of Labor in Society. Translated by W. D. Halls. New York: Free Press, 1997.

Kropotkin, Peter. Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution. London: McClure, Phillips & Co., 1902.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994.

Mead, Margaret. Culture and Commitment: A Study of the Generation Gap. Garden City, NY: Natural History Press, 1970.

Ostrom, Elinor. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Putnam, Robert D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000.

Tönnies, Ferdinand. Community and Society (Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft). Translated and edited by Charles P. Loomis. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1957.

Tuan, Yi-Fu. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1977.

Turner, Victor. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Chicago: Aldine Publishing, 1969.

Wilber, Ken. A Brief History of Everything. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2000.

Wilson, Edward O. The Social Conquest of Earth. New York: Liveright Publishing, 2012.