Table of Contents

- Cosmic Time – Observing the Heavens

How the stars, sun, and moon gave rise to the first rhythms of human time - Early Calendars of Civilization

Agricultural cycles, religious observances, and the birth of civil order - The Gregorian Revolution

Reforming the calendar to align with the solar year and ecclesiastical authority - Religious and Cultural Calendars

A world of sacred time: diversity, tradition, and temporal pluralism - The Invention of the Clock

From sundials and water clocks to pendulums and personal timepieces - The Standardization of Time

Railroads, telegraphs, and the emergence of global time zones - Atomic Time and Coordinated Universal Time (UTC)

The quantum foundation of precision time in the modern world - Modern Proposals for a Universal Calendar

Reimagining the year: symmetry, simplicity, and scientific neutrality - A Scientific and Secular Approach to Global Time

Designing a time system for a planetary civilization - Toward a Universal Solution

Principles, prototypes, and pathways to reforming world timekeeping - Conclusion – Time as a Shared Inheritance

Honoring the past, synchronizing the present, and preparing for the future

Introduction

“Time is the wisest counselor of all.” — Pericles

Time is not only the medium through which all life unfolds—it is also a system humanity has sought to understand, measure, and master. From the movement of the stars to the ticking of atomic clocks, the history of timekeeping mirrors the evolution of human civilization itself.

Our ancestors gazed at the heavens to mark the passing of seasons and sow their crops. Over millennia, they refined these observations into calendars and clocks—tools that would come to structure societies, rituals, economies, and empires. With the rise of science and global communication, humanity confronted a new challenge: how to reconcile diverse cultural systems of time with the need for universal coordination in an interconnected world.

Today, we live by Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), navigate a map of time zones, and refer to a Gregorian calendar rooted in Christian tradition. Yet, discrepancies persist. Religious calendars differ by months and years. Leap seconds disrupt atomic precision. The very labels of our calendar—BC and AD—carry theological implications in an age striving for secular, inclusive norms.

This article explores the full arc of the history of timekeeping: from ancient sundials and sacred calendars to atomic clocks and contemporary proposals for global synchronization. Along the way, it considers the philosophical and political dimensions of how we reckon time and what it might mean to construct a truly universal system.

As humanity ventures beyond Earth and into a digital, planetary civilization, the question of timekeeping becomes more than a technical curiosity. It becomes a matter of shared reality.

1. Cosmic Time – Observing the Heavens

Long before mechanical clocks and coordinated calendars, humans looked upward to the sky to find order in the chaos of time. The motion of the sun, moon, and stars provided the first and most enduring reference points for measuring time. These celestial patterns were not only practical—they were imbued with spiritual and philosophical meaning, binding human life to the cosmos.

The Solar Cycle and the Birth of the Day

The most immediate experience of time came with the daily rising and setting of the sun. Early humans marked days by the passage of light and shadow, which gave rise to sundials and other primitive tools to track solar motion. The apparent movement of the sun across the sky divided the day into morning, noon, and night, leading to the earliest divisions of time.

Lunar Rhythms and the Month

The moon’s cycle of waxing and waning became the basis for the “month”—a natural time unit shorter than the solar year. Many ancient calendars, such as the Hebrew, Islamic, and Chinese systems, are rooted in lunar or lunisolar patterns. The phases of the moon were readily visible and culturally resonant, often tied to fertility, agriculture, and ritual.

The Year: Solstices and Equinoxes

The annual cycle—marking the progression of seasons—was essential for agriculture and survival. People tracked the sun’s changing position on the horizon, leading to awareness of the winter and summer solstices (the shortest and longest days) and the equinoxes (when day and night are equal). Megalithic structures such as Stonehenge in England, Nabta Playa in Egypt, and Chaco Canyon in the American Southwest are aligned to these seasonal events, suggesting calendrical and ceremonial purposes.

Stellar Timekeeping and the Zodiac

The fixed stars and constellations also played a critical role. The appearance or disappearance of certain stars at dawn or dusk marked seasonal transitions. Ancient Egyptians, for instance, timed the flooding of the Nile with the heliacal rising of Sirius. Over time, this stellar tracking evolved into systems like the Babylonian zodiac, which divided the sky into twelve signs through which the sun appears to travel over the course of a year.

Celestial Spheres and Philosophical Time

The Greeks elevated these observations into cosmic theories. Plato, Aristotle, and later Ptolemy conceptualized time as a function of celestial motion—cyclical, eternal, and divinely ordered. In many ancient cultures, the heavens were thought to reflect a metaphysical order, with time seen not merely as a measure of change but as a sacred geometry of the universe.

From Observers to Astronomers

What began as practical sky-watching gradually became systematic observation. By the first millennium BCE, civilizations such as the Babylonians, Chinese, and Mayans developed astronomical records with extraordinary accuracy. These records informed calendar reform, navigation, agriculture, and early sciences. The sky became not just a clock but a scientific archive—a cosmic ledger etched in light.

2. Early Calendars of Civilization

As human societies evolved from nomadic tribes to settled agricultural civilizations, the need for consistent, shared systems of timekeeping became critical. Calendars—structured frameworks for measuring time—emerged as tools not only for farming, but for organizing festivals, religious observances, taxation, governance, and social cohesion. These early systems reveal humanity’s attempt to bring cosmic rhythms into daily order.

The Sumerian and Babylonian Calendars

The Sumerians of Mesopotamia were among the first to record time in systematic fashion. They developed a lunisolar calendar based on 12 lunar months, periodically adjusted with intercalary months to stay aligned with the solar year. The Babylonians inherited and refined this model, introducing a 19-year cycle (the Metonic cycle) to harmonize lunar and solar calendars. Their innovations—such as the seven-day week tied to planetary deities—would profoundly influence later Jewish, Islamic, and Christian timekeeping systems.

Ancient Egyptian Solar Precision

The ancient Egyptians based their calendar on the solar year. They observed that the Nile’s annual flooding coincided with the heliacal rising of Sirius, prompting the development of a 365-day calendar composed of 12 months of 30 days, plus five festival days. Though lacking leap years, it was remarkably accurate over short spans. Their solar calendar would later influence the Julian and Gregorian reforms.

The Chinese Lunisolar Calendar

The Chinese developed a complex lunisolar calendar by the Shang dynasty (c. 1600 BCE). It combined lunar months with solar terms (known as jieqi) to track the agricultural cycle and celestial phenomena. This calendar was closely linked to dynastic power—each emperor inaugurated a new era with calendar reforms, asserting harmony with the cosmos. Chinese calendar-making included eclipse prediction, star cataloguing, and rigorous mathematical astronomy.

The Hindu Calendar Systems

Indian civilization produced multiple calendrical systems based on sidereal (star-based) rather than tropical (season-based) astronomy. The Vedic texts and later Hindu astronomical treatises like the Surya Siddhanta developed detailed schemes for intercalation, lunar phases, and planetary motion. Hindu calendars remain diverse, with both lunar and solar variants used regionally for religious festivals and daily life.

The Mayan Calendar Complex

In the Americas, the Mayans devised one of the most sophisticated ancient calendrical systems. Their calendar included three interlocking cycles: the 260-day ritual Tzolk’in, the 365-day solar Haab’, and the Long Count, a linear system used to track vast spans of history. Their calculations were so precise that they could predict solar eclipses and planetary alignments with near-modern accuracy.

The Roman Calendar and Julian Reform

The Roman calendar underwent several transformations, beginning with a lunar system attributed to Romulus and reformed by Numa Pompilius. By the late Republic, political manipulation had rendered the calendar chaotic. Julius Caesar, with the help of Alexandrian astronomers, instituted the Julian calendar in 46 BCE—a solar calendar with 365 days and a leap year every four years. It remained in widespread use for over 1,600 years.

These early systems—though regionally distinct—demonstrate humanity’s shared ambition to align daily life with the great cycles of the cosmos. The calendar, once a sacred and civic instrument, became a mark of sovereignty, science, and civilization.

3. The Gregorian Revolution

By the late Middle Ages, Europe’s calendar no longer accurately matched the seasons. Over centuries, the small annual misalignment in the Julian calendar—a discrepancy of approximately 11 minutes per year—had accumulated to a full ten days. This misalignment posed both practical and theological problems, especially for calculating the date of Easter. The solution would require the most significant calendar reform in Western history.

The Julian Legacy and Its Drift

The Julian calendar, introduced by Julius Caesar in 46 BCE, assumed a solar year of 365.25 days. It added a leap day every four years to correct for the fractional day. While this was a major improvement over earlier Roman systems, the true solar year is closer to 365.2422 days. That seemingly negligible difference caused the calendar to drift roughly one day every 128 years. By the 16th century, the spring equinox was occurring around March 11 rather than March 21, throwing off the liturgical calendar.

The Problem of Easter

The calculation of Easter—a moveable feast based on the vernal equinox and the full moon—had become increasingly inaccurate. Church authorities feared this temporal error undermined both the precision and the authority of the Christian liturgical year. Calendar reform became a theological imperative.

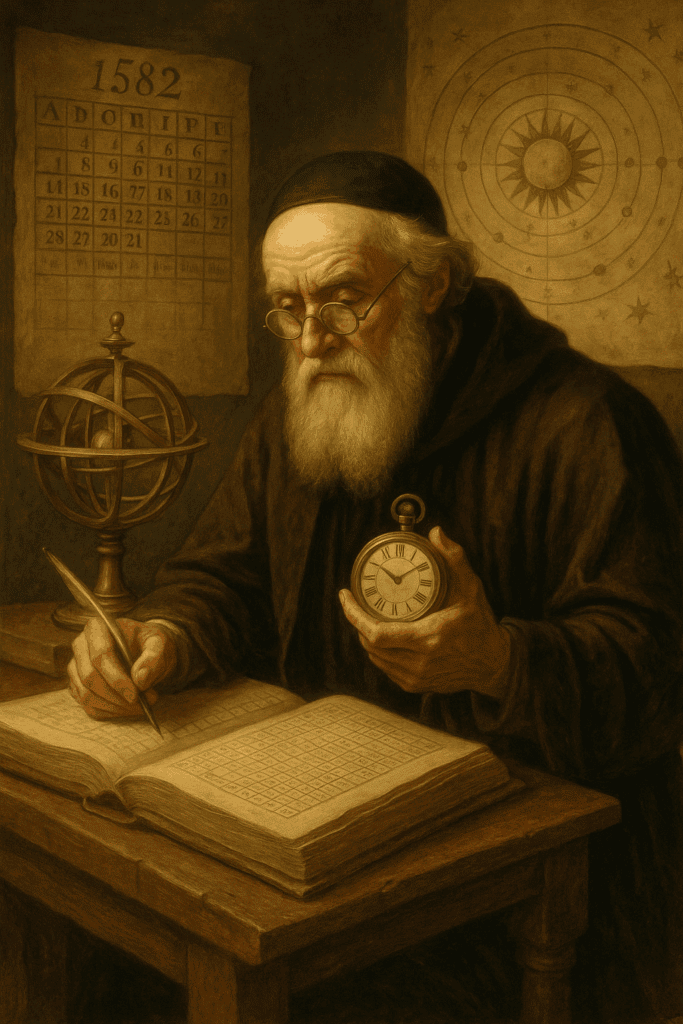

Pope Gregory XIII and the 1582 Reform

In response, Pope Gregory XIII convened a commission of astronomers and mathematicians, including the Jesuit Christopher Clavius. They proposed a calendar reform that would realign the calendar with the solar year and prevent future drift. The key changes included:

- Dropping 10 days to realign the equinox (October 4, 1582 was followed by October 15)

- Modifying leap year rules: years divisible by 100 would not be leap years unless also divisible by 400 (e.g., 1600 and 2000 are leap years, but 1700, 1800, and 1900 are not)

This new system, now known as the Gregorian calendar, approximates the solar year to within 26 seconds—resulting in a drift of just one day every 3,300 years.

Slow and Controversial Adoption

While Catholic countries adopted the new calendar almost immediately (Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Poland in 1582), Protestant and Orthodox countries were slower to comply, viewing the reform with suspicion. Britain and its colonies did not adopt the Gregorian calendar until 1752, at which point they had to correct by 11 days. Russia held to the Julian calendar until the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. Even today, some Orthodox churches continue to use the Julian calendar for religious observances.

A New Global Standard

Despite its religious origins, the Gregorian calendar gradually became the civil standard across much of the world due to colonial expansion, scientific necessity, and global coordination. It is now the de facto international calendar, used in diplomacy, commerce, and technological systems—even in many cultures that maintain separate religious calendars for spiritual life.

The Gregorian reform was not merely a correction of celestial error—it was a powerful statement of authority by the Catholic Church, a feat of astronomical precision, and a harbinger of global synchronization. It laid the foundation for a new era of timekeeping: one that increasingly demanded accuracy, consistency, and universal agreement.

Excellent. Here’s the draft for:

4. Religious and Cultural Calendars

While the Gregorian calendar has become the dominant civil timekeeping system worldwide, it is by no means the only one in use. Across the globe, diverse cultures maintain traditional calendars rooted in religious, agricultural, and philosophical worldviews. These calendars do more than track time—they shape identity, ritual, and cosmology. The coexistence of multiple calendar systems highlights the complex relationship between culture and chronology.

The Jewish Calendar

The Hebrew calendar is a lunisolar system used primarily for religious observances. Months begin with the new moon, but the calendar is periodically adjusted with a leap month (Adar II) to keep festivals aligned with the solar year. Passover, for example, must fall in spring. The calendar counts years from the traditional date of creation (currently year 5785 in 2025 CE) and is essential for determining dates for holidays, Torah readings, and rituals. Its complexity reflects deep theological and astronomical considerations.

The Islamic (Hijri) Calendar

In contrast to the lunisolar Jewish system, the Islamic calendar is purely lunar. Each year consists of 12 lunar months, totaling approximately 354 or 355 days. There is no intercalation, so Islamic months shift through the solar year. As a result, Ramadan, the sacred month of fasting, can occur in any season. The calendar begins with the Hijra—Muhammad’s migration from Mecca to Medina in 622 CE—and is used across the Muslim world for religious purposes, even in countries that use the Gregorian calendar for civil affairs.

The Hindu Calendars

India’s calendrical diversity is vast, with multiple regional systems. Most are lunisolar, based on sidereal (star-relative) astronomy. The Panchangam, or Hindu almanac, provides detailed daily information on lunar phases, planetary conjunctions, and auspicious times. The calendar is essential for religious festivals such as Diwali and Holi, and for determining the timing of rites and pilgrimages. The calendar’s regional flexibility reflects the pluralistic structure of Hindu civilization.

The Buddhist Calendars

Buddhist countries often use their own calendars for religious observances. In Theravāda Buddhist traditions (e.g., Thailand, Sri Lanka), calendars are often lunisolar and count years from the Buddha’s parinirvana, traditionally dated to 543 BCE. The Tibetan Buddhist calendar combines Indian lunisolar elements with Chinese astrological features, resulting in a highly complex and symbolic system. These calendars determine the timing of monastic ceremonies, public festivals, and astrological rituals.

East Asian Calendars

In China, Korea, and Japan, traditional lunisolar calendars continue to influence culture. The traditional Chinese calendar is dated from 2637 BCE, with the reign of the Yellow Emperor, Huang Di. The Chinese calendar determines the timing of Lunar New Year and other traditional festivals. It incorporates solar terms, lunar months, and a 60-year cycle based on combinations of celestial stems and terrestrial branches. Although China officially adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1912 for civil use, the traditional calendar still guides cultural life.

The Cultural Challenge of Global Synchronization

Despite the practical need for a unified global calendar, cultural and religious calendars persist because they encode meaning, memory, and belonging. Attempts to replace or homogenize them have often met resistance—not only because of theology, but because time itself is a symbol of heritage. The Gregorian calendar, though universal in commerce, is not truly global in spirit.

Religious and cultural calendars reflect humanity’s plural relationship with time. While science seeks precision and universality, tradition seeks meaning and connection. Any future effort toward a universal calendar must reckon not only with astronomical accuracy, but with the human need for identity and ritual embedded in time itself.

5. The Invention of the Clock

While calendars allowed civilizations to measure time on the scale of days, months, and years, the invention of the clock enabled humans to divide the day itself into ever smaller, more manageable units. This leap in timekeeping—from celestial to mechanical—transformed not only technology, but the human experience of life, labor, and ritual.

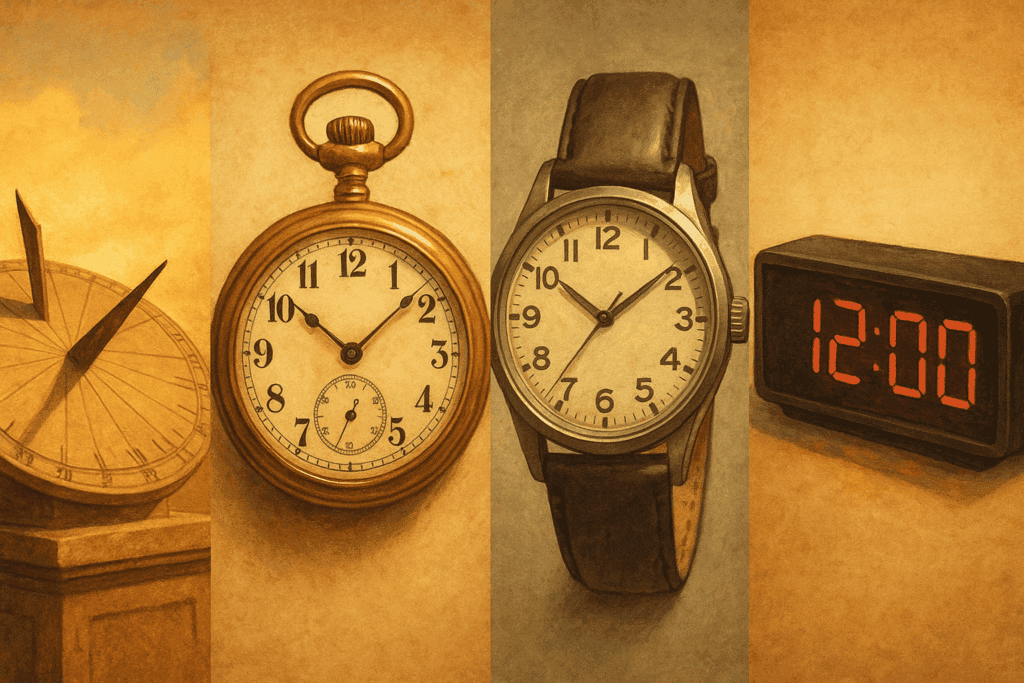

Sundials and Water Clocks

The earliest devices for measuring parts of the day relied on natural elements. Sundials, found in ancient Egypt, Babylon, China, and Greece, used the shadow cast by a gnomon to mark the sun’s passage through the sky. These instruments could divide daylight into hours, but they were limited to sunny days and varied by season and latitude.

Water clocks (clepsydrae) offered a more consistent alternative. In these devices, time was measured by the regulated flow of water into or out of a container. Used in ancient Egypt, India, and especially Greece, water clocks allowed for timekeeping at night or indoors. Greek engineers developed elaborate versions with gears and escapements, foreshadowing the mechanical clock.

Medieval Innovations: Monastic Time

In Christian Europe, monastic life demanded strict scheduling of prayers, rituals, and labor. This need drove innovation. By the 10th century, bell towers regulated communal time with the ringing of hours. Mechanical weight-driven clocks began to appear in the 13th century, using a verge escapement mechanism to regulate the release of energy. These clocks were monumental public devices, installed in town squares and cathedral towers to symbolize civic and ecclesiastical authority.

The Rise of Precision: Pendulum and Spring

The 17th century marked a turning point. In 1656, Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens invented the pendulum clock, dramatically improving accuracy. Shortly afterward, spring-driven mechanisms enabled the creation of pocket watches, making personal timekeeping portable.

These innovations reflected a changing worldview: time was no longer the province of nature or ritual alone—it became a quantifiable, uniform resource. The mechanization of time paralleled the rise of modern science, capitalism, and industrial labor.

The Wristwatch and Democratization of Time

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, watches became increasingly miniaturized, affordable, and widespread. The wristwatch, once considered feminine, was popularized among soldiers during World War I for its practicality in combat. By the mid-20th century, wristwatches had become everyday items—symbols of punctuality, professionalism, and technological progress.

Quartz Revolution and the Digital Era

The next great leap came with the quartz clock in the 1920s, which used the regular vibrations of a quartz crystal under electrical current to keep time with unprecedented accuracy. In 1969, Seiko released the first quartz wristwatch, ushering in the digital era of timekeeping. Digital clocks, atomic synchronization, and networked systems would soon reshape everything from global finance to daily alarms.

The invention of the clock was not a single moment, but a long and layered evolution—from elemental tools to precision instruments, from sacred rhythms to the regulated pulse of the modern world. As clocks became smaller and more accurate, so too did humanity’s awareness of time’s passing—and its value.

6. The Standardization of Time

With the rise of industrial society, the invention of mechanical clocks, and the spread of railroads and telegraphs, a new challenge emerged: coordination. Local solar time, which had served communities well for centuries, became a barrier in a rapidly shrinking world. Timekeeping needed not just accuracy—but standardization.

Local Time and the Confusion of Clocks

Before the 19th century, each city kept its own local time based on the sun’s position at noon. Noon in Paris was different from noon in London or Rome. This posed little problem for agrarian societies or even early travelers. But with the expansion of railway networks, which operated on precise timetables across long distances, the variation in local time became a source of confusion, missed trains, and economic inefficiency.

The Railway Clock and “Railway Time”

Britain was the first to confront this issue. In the 1840s, railway companies began using Greenwich Mean Time (GMT)—the mean solar time at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich—as the standard for all schedules, regardless of local solar noon. Station clocks were set to this new “railway time,” and passengers had to adjust. By the 1850s, GMT was increasingly adopted across Britain, setting a precedent for national and international time coordination.

Telegraphs and the Speed of Time

The telegraph, introduced in the mid-19th century, added new urgency to synchronizing clocks. Messages could now travel faster than people, but only if sender and receiver agreed on the same time. The logic of commerce, communication, and coordination demanded a global system.

The International Meridian Conference (1884)

Recognizing the need for worldwide standardization, 25 nations convened in Washington, D.C., in 1884. The outcome was a landmark agreement:

- The Greenwich Meridian was declared the prime meridian (0° longitude)

- The globe was divided into 24 standard time zones, each roughly 15° of longitude apart

- Universal Time (UT), based on GMT, was adopted as the baseline for world time

While not every country immediately implemented time zones, this conference laid the foundation for global timekeeping—a geopolitical as well as scientific achievement.

Time Zones and National Control

Countries gradually adopted time zones and established national time standards. Some created unique offsets (like India’s +5:30 or Nepal’s +5:45) for political or practical reasons. Daylight Saving Time (DST) was later introduced in many regions to adjust daylight hours seasonally, though it remains controversial and inconsistently applied.

From GMT to UTC

As science progressed, so too did the precision of time. In 1972, Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) replaced GMT as the world’s official time standard. UTC is based on atomic clocks rather than Earth’s rotation and is occasionally adjusted with leap seconds to remain aligned with astronomical time. It governs everything from GPS satellites to internet servers and international broadcasts.

The standardization of time was one of the most transformative steps in modern history. It unified the clocks of the world, enabling synchronized travel, communication, trade, and science. It turned time into a shared, planetary framework—an invisible architecture underpinning the machinery of global civilization.

7. Atomic Time and Coordinated Universal Time (UTC)

As human activity extended into realms where microseconds matter—spaceflight, high-frequency trading, GPS navigation—the limitations of astronomical timekeeping became evident. Earth’s rotation, while broadly reliable, is irregular at fine scales. To meet the demands of modern science and technology, a new foundation for timekeeping was needed—one rooted not in the skies, but in the atoms themselves.

The Invention of the Atomic Clock

The idea of atomic time emerged in the early 20th century, building on quantum theory. In 1949, the U.S. National Bureau of Standards (now NIST) developed the first atomic clock using ammonia molecules. But it was in 1955 that British physicists Louis Essen and Jack Parry unveiled the first caesium-133 atomic clock at the National Physical Laboratory in the UK. This device measured time based on the frequency of radiation emitted when electrons in caesium atoms change energy levels—a phenomenon constant across time and space.

One second was redefined in 1967 by the International System of Units (SI) as:

“the duration of 9,192,631,770 periods of the radiation corresponding to the transition between two hyperfine levels of the ground state of the caesium-133 atom.”

This marked a radical shift: time was no longer based on Earth’s motion, but on quantum phenomena.

The Rise of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC)

To manage this new precision, the global community established Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) in 1972. UTC combines the regularity of International Atomic Time (TAI) with occasional adjustments—leap seconds—to keep it aligned with Universal Time 1 (UT1), which is based on Earth’s rotation.

- TAI: Pure atomic time, without any corrections for Earth’s rotation.

- UTC: Atomic time + leap seconds to stay within 0.9 seconds of UT1.

- UT1: Mean solar time, tracked by astronomical observations.

Leap seconds are added (or theoretically subtracted) at the end of June or December to account for irregularities in Earth’s spin. These adjustments are decided by the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS).

Why Atomic Time Matters

Atomic time underpins nearly every major global technology:

- GPS and satellite systems use atomic clocks onboard to triangulate precise locations.

- Internet networks rely on synchronized time protocols (like NTP) for data integrity.

- Scientific experiments in particle physics, astronomy, and quantum computing demand nanosecond accuracy.

- Financial systems timestamp transactions for global markets, compliance, and security.

The growing reliance on precision time has made atomic clocks the heartbeat of modern civilization.

Controversy Over Leap Seconds

While necessary to align human time with the Earth, leap seconds cause problems. They can crash software, disrupt GPS, and create ambiguity in time-sensitive systems. For these reasons, a global consensus is forming to eliminate leap seconds in the future, letting atomic time diverge slowly from Earth time. By 2022, the ITU and other international bodies proposed suspending leap seconds after 2035.

Atomic time marks a profound philosophical and scientific shift—from the rhythms of the cosmos to the constants of matter. It offers a level of precision unimaginable to ancient astronomers, yet it raises new questions about the nature of time itself. Are we measuring reality, or constructing it anew?

8. Modern Proposals for a Universal Calendar

While Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) has become a global standard for precise clock time, the Gregorian calendar—rooted in 16th-century Christian Europe—remains the dominant civil calendar. Yet many thinkers, scientists, and reformers have proposed alternative calendars better suited to a secular, global, and rational age. These proposals aim to simplify timekeeping, eliminate irregularities, and create a truly universal system for humanity.

Problems with the Gregorian Calendar

Though elegant in its leap year corrections, the Gregorian calendar is:

- Irregular: Months vary in length from 28 to 31 days, making calculations complex.

- Asymmetrical: The year cannot be evenly divided into quarters, weeks, or consistent intervals.

- Culturally specific: It retains religious references (e.g., BC/AD) that do not reflect a global, multicultural society.

- Non-repeating: Each year starts on a different weekday, complicating long-term planning.

These limitations inspired a series of proposals in the 19th and 20th centuries for more rational, standardized calendars.

1. The International Fixed Calendar (IFC)

Proposed by Moses Cotsworth in 1902, the IFC consists of:

- 13 months, each with 28 days (exactly 4 weeks)

- A total of 364 days, with one additional “Year Day” outside the week cycle

- A leap year adds an extra “Leap Day” after June 28

This calendar repeats the same format every year, making planning easier. It was adopted by George Eastman of Kodak for internal business use for decades, but never achieved global traction due to religious and cultural objections—especially to altering the seven-day week cycle.

2. The World Calendar

Developed by Elisabeth Achelis in the 1930s, this calendar preserves the 12-month structure but makes each quarter identical:

- Each quarter has 91 days (two months of 30 days, one of 31)

- Total: 364 days + 1 “World Day” (not part of any week)

- Leap years add a second extra day, “Leap Day,” every four years

The World Calendar is more compatible with Gregorian months but still requires breaking the seven-day week—a key reason why religious groups (especially Christians and Jews) opposed it.

3. The Holocene Calendar

Proposed by scientist Cesare Emiliani in 1993, the Holocene Calendar shifts the Gregorian calendar forward by 10,000 years to reflect the start of the Holocene epoch—the geological age of modern humanity. Year 1 HE = 10,000 BCE. For example, 2025 CE becomes 12025 HE.

Its advantages:

- A neutral epoch not based on any religious figure

- A continuous timeline of human civilization, starting with agriculture and the first cities

This reform doesn’t alter the structure of the calendar, only its year numbering, making it easy to implement in scientific contexts.

4. The Symmetry454 Calendar

A modern proposal that:

- Keeps 12 months

- Arranges months into 4-5-4 week patterns per quarter

- Uses leap weeks rather than leap days

- Ensures that every date falls on the same weekday each year

It preserves the seven-day week and avoids “blank days,” aiming for minimal disruption to religious rhythms while providing perfect calendar symmetry.

Challenges to Reform

Despite their logical elegance, universal calendar reforms face several obstacles:

- Religious tradition: Breaking the weekly cycle or modifying holy days is widely resisted

- Institutional inertia: Government, legal, educational, and financial systems are deeply rooted in Gregorian timekeeping

- Global coordination: No international body has the authority or consensus to impose calendar change

The dream of a universal calendar reflects a deeper aspiration: to create a common temporal language for a global civilization. But that dream must contend with the power of tradition, the rhythm of ritual, and the complexity of collective change.

9. A Scientific and Secular Approach to Global Time

In an age of space travel, artificial intelligence, and instantaneous global communication, the patchwork of religious, cultural, and national calendars stands in contrast to our increasingly interconnected reality. The need for a timekeeping system that is neutral, rational, and universal—yet respectful of diversity—is more pressing than ever. Can we create a framework of global time that unites scientific precision with human inclusivity?

Time Without Theocracy

Most dominant calendar systems today, including the Gregorian, Hijri, Hebrew, and Buddhist calendars, are tied to religious narratives or sacred histories. While these serve vital cultural roles, they are not universally shared. A secular global calendar would:

- Avoid the privileging of any one religion or culture

- Use a scientific epoch, such as the Holocene or Common Era

- Allow for interoperability with existing religious calendars for ceremonial use

Such an approach mirrors the move from religious to scientific explanations in medicine, governance, and ethics—offering neutrality without erasure.

The Astronomical Foundations

A scientifically grounded time system would be based on stable, observable phenomena:

- The solar year (365.2422 days) defines the orbit of Earth

- The lunar month (29.53 days) remains culturally relevant, even if not ideal for calendars

- Atomic time offers unmatched precision, with accuracy down to billionths of a second

Blending these layers would allow a multi-tiered timekeeping system: daily, seasonal, and universal, anchored in both astronomy and physics.

Global Consistency for Civil Use

A secular calendar and time standard would enable:

- Simplified scheduling across nations, corporations, and institutions

- Easier historical comparison and scientific data logging

- A framework for interplanetary timekeeping as humanity ventures beyond Earth

Rather than replacing all religious and cultural calendars, a layered system could emerge:

- Universal Calendar for international civil and scientific use

- Local Calendars for cultural and religious observances

Such a framework mirrors the structure of language: English is the global lingua franca of science and diplomacy, yet local languages continue to thrive.

The Psychological and Philosophical Challenge

Time is not just a tool—it is a story. Any change to how we keep it must acknowledge:

- The human need for ritual and familiarity

- The existential comfort found in seasonal cycles, sacred dates, and ancestral traditions

- The perception of time not only as linear (scientific) but cyclical (spiritual, ecological)

To move forward, we must construct not only a rational system, but a meaningful one—one that balances logic with lived experience.

As global challenges—from climate change to space exploration—demand coordinated action, our fragmented timekeeping practices stand as a relic of pre-global society. A scientific and secular approach offers not just efficiency, but a vision of temporal unity worthy of a planetary civilization.

10. Toward a Universal Solution

The journey from watching stars to programming satellites has revealed a central truth: time is a shared foundation. Yet the systems we use to track it remain fragmented—religious, cultural, political, and technical legacies layered atop one another. In this final section, we imagine what a truly universal solution to timekeeping might look like: one that honors both scientific precision and human diversity.

Principles for a Global Timekeeping System

A universally adopted system should be:

- Scientifically Accurate: Rooted in the solar year and atomic time, not in myth or arbitrary tradition.

- Culturally Respectful: Flexible enough to coexist with religious and regional calendars.

- Practical and Predictable: Regular months, fixed weeks, and uniform dates across years.

- Technologically Compatible: Aligned with UTC and ready for future digital, quantum, and space-based systems.

- Philosophically Neutral: Avoiding era names tied to particular civilizations or faiths.

Layered Time: A Coexisting Model

Rather than impose a single calendar, a viable model may use layered timekeeping:

- Global Standard Time (UTC): Used in digital systems, science, navigation, and trade.

- Universal Civil Calendar: A reformed calendar (e.g. Symmetry454 or Holocene) for global use in business, international law, and secular institutions.

- Cultural Calendars: Maintained independently for festivals, liturgy, identity, and local heritage.

This layered approach allows for standardization without cultural erasure, much like metric units coexist with imperial ones in everyday life.

Prototype: A Rational Calendar-Year

Imagine a Universal Calendar with:

- 12 equal months of 30 days

- 5–6 festival or “world days” outside the week cycle

- Each year starts on the same weekday

- Leap years add an intercalary day every 4 years

- Year counted from a scientifically neutral epoch (e.g. 10,000 BCE = 1 HE)

Such a structure would make scheduling, accounting, and international cooperation vastly simpler.

Governance and Adoption

To implement such a solution, global cooperation would be essential:

- A United Nations agency or scientific consortium could steward reform

- Educational institutions could pilot dual-calendar systems

- Open-source, interoperable software could provide daily calendar conversion and visualization

Gradual, voluntary adoption—especially in scientific, educational, and technological fields—could pave the way for broader consensus.

Time for the Space Age

A universal time system must also look beyond Earth:

- Mars has a day 39 minutes longer than Earth’s—how will Martian time be coordinated with Earth time?

- Lunar colonies, satellites, and interplanetary missions will need a space-time framework

- A universal calendar can be the first cultural artifact of a multi-planetary species

To move toward a universal solution is not simply to create a better tool—but to declare a shared destiny. In time, as in science and human rights, the future belongs not to one culture or continent, but to all of us. The reform of timekeeping may one day symbolize our emergence as a planetary civilization, united not only by space, but by the rhythms of reason.

Conclusion – Time as a Shared Inheritance

Time is both universal and deeply personal. It is the pulse of the cosmos and the cadence of our days; the measure of eternity and the rhythm of a heartbeat. Across the arc of civilization, we have sought to tame time—first with shadow and star, then with clock and code. Each advance in timekeeping reflects a step in our shared journey toward understanding nature, organizing society, and envisioning the future.

From the sacred calendars of ancient peoples to the precise frequencies of atomic clocks, the history of timekeeping is also a history of our aspirations: to plant, to pray, to build, to explore, to connect. But now, in an era of global interdependence and interplanetary ambition, our old divisions in how we count time stand in tension with the realities of our world.

The Gregorian calendar and Coordinated Universal Time have served us well—but they are not the final word. As we step further into a digital, data-driven, and spacefaring future, the need for a scientifically grounded, culturally inclusive, and globally adopted system of timekeeping becomes not just a convenience, but a necessity.

To reform how we keep time is not to erase the past, but to carry it forward into coherence—a recognition that time, like language, evolves. It is the ultimate commons: invisible, invaluable, and inescapably shared.

Let us then take the measure of our moment—and design a system of time that reflects who we are, how far we’ve come, and what we aspire to become. In doing so, we do not merely mark time. We make it.