Table of Contents

- Introduction – Living Spaces as Systems of Life and Culture

Defining architecture, landscaping, and city planning as human-environment systems. - A Brief History of Architecture Around the World

From ancient shelters to sacred spaces, monumental works, and modern design. - A History of Gardens and Landscaping

From Mesopotamian orchards to Japanese Zen gardens and urban green spaces. - The Evolution of City Planning

Ancient cities, medieval towns, modern metropolises, and postmodern urban design. - Science and Spirituality in Design: Feng Shui and Other Geomantic Traditions

Rational analyses of energy flow, natural orientation, and environmental harmony. - Principles of Architectural Design and Construction

Function, form, structure, space, materials, light, durability, and beauty. - Principles of Gardening and Landscaping

Soil, water, flora, climate, composition, aesthetics, and ecological function. - Principles of City Planning

Zoning, transportation, density, public spaces, and social equity. - The Science and Technology of Building and Planning

Structural mathematics, materials science, utilities, energy, safety, and infrastructure. - Sustainable and Green Design

Innovations in eco-architecture, permaculture, green roofs, solar cities, and biophilic design. - Economics, Policy, and Governance of Living Spaces

Regulation, financing, class access, housing crises, and land ownership models. - The Influence of King Charles III and Other Visionaries

Traditionalism, environmentalism, and critiques of modernist planning. - Case Study: Jakarta and Nusantara – Capital Planning in the Age of Climate Change

Environmental, social, and design considerations of Indonesia’s new capital. - Nested Systems: From Home and Garden to the Global Ecological Urban Network

Living spaces as interdependent scales in a planetary web of culture and nature. - Conclusion – Designing the Future of Life on Earth

Integrating science, aesthetics, ecology, and social values in built environments.

1. Introduction – Living Spaces as Systems of Life and Culture

Throughout history, the places where we live—our homes, gardens, buildings, and cities—have been more than mere shelters. They are expressions of our values, reflections of our knowledge, and structures that shape how we live, move, and relate to one another and to nature. Architecture, landscaping, and city planning are not simply matters of aesthetics or utility; they are sciences and arts that encode centuries of cultural wisdom, technical innovation, and environmental adaptation.

As human beings evolved from nomadic foragers to agriculturalists, and later into industrial and digital citizens, our living spaces evolved too. Villages became cities; tents gave way to temples, palaces, apartments, and skyscrapers; forests were turned into parks; and roads into digital smart corridors. With each transformation, we have had to reconcile competing needs: shelter and openness, tradition and innovation, economic efficiency and ecological sustainability.

This article explores the deep history and current frontiers of how humans shape the spaces in which they live. We will travel across civilizations and eras—from the mudbrick cities of Mesopotamia to the glass towers of the 21st century, from classical gardens to contemporary ecological landscaping, from ancient citadels to intelligent megacities. Along the way, we will examine the scientific principles, technologies, and environmental systems that make these living spaces possible—and sustainable.

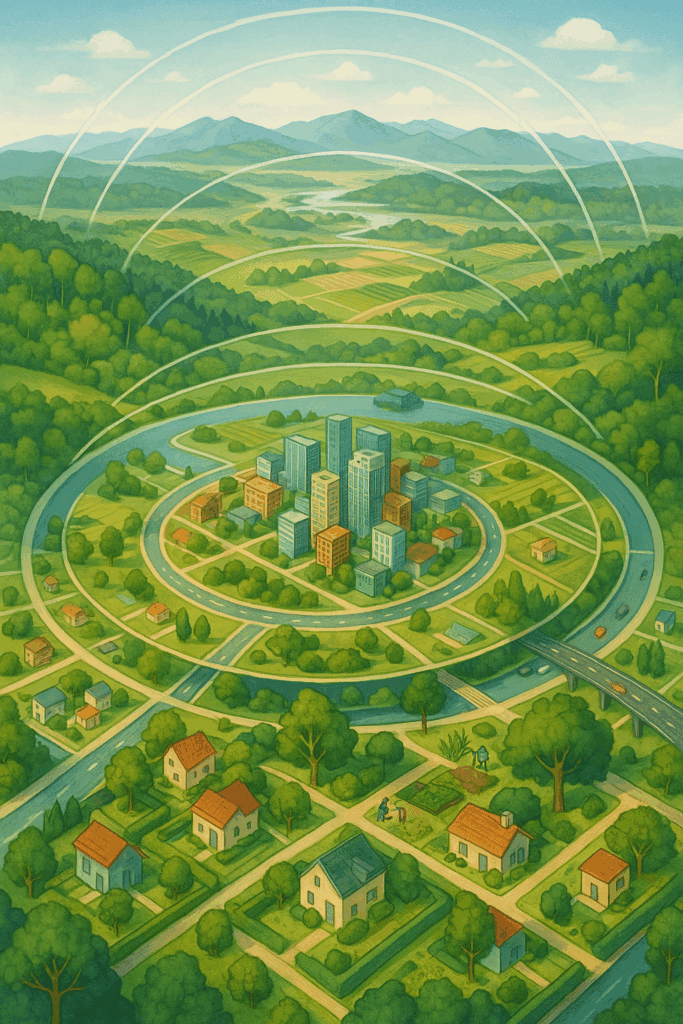

We also consider living spaces as systems nested within other systems. A home operates within a neighborhood, which functions within a city, which interacts with its region and biome, and ultimately contributes to the global ecological and civic landscape. From the smallest courtyard to vast urban ecosystems, each level of planning demands not only design skill, but deep understanding of geology, hydrology, biology, climate, economics, governance, and human behavior.

Today, as humanity confronts climate change, urban crowding, resource scarcity, and rising inequality, the design of living spaces has become a moral and scientific imperative. In reimagining our built environments, we reimagine our relationship with the Earth and with one another. This article aims to provide a comprehensive, interdisciplinary look at the history, science, and future of living spaces—so we can build a world that is not only livable, but flourishing.

2. A Brief History of Architecture Around the World

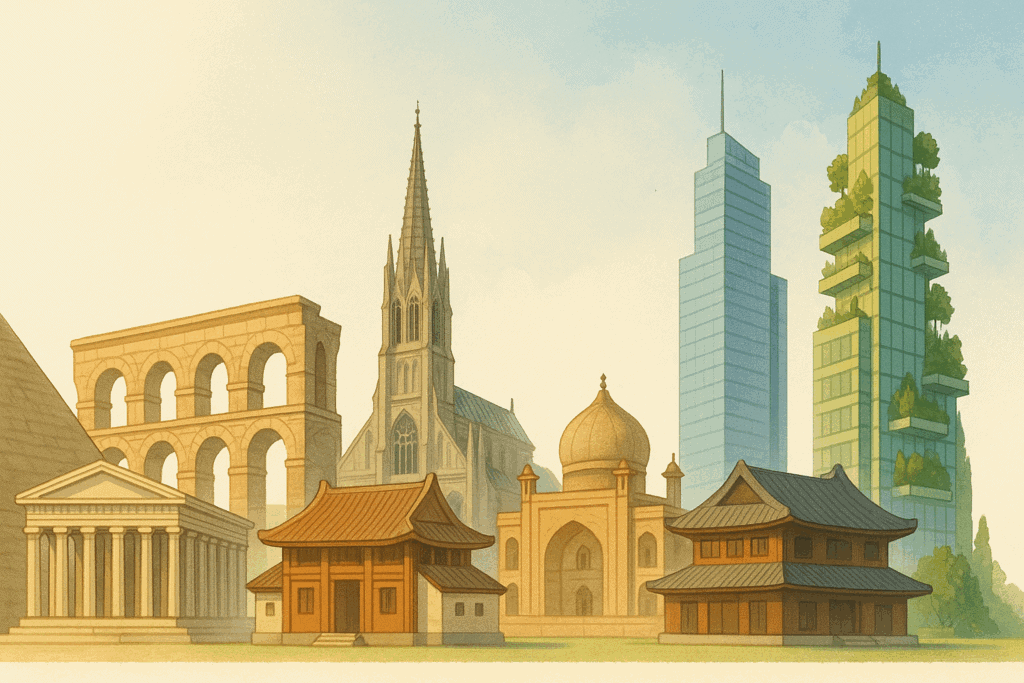

Architecture is one of the oldest forms of human expression—simultaneously artistic, functional, social, and spiritual. Long before recorded history, early humans shaped natural spaces into habitable forms: caves, huts, tents. As societies advanced, architecture developed into a codified discipline reflecting culture, belief, climate, technology, and economy. Across time and geography, architecture has evolved into a vast, diverse record of civilization itself.

2.1 Prehistoric and Ancient Architecture

The earliest known architectural efforts were megalithic structures and communal dwellings. Sites such as Göbekli Tepe (Turkey, 10th millennium BCE) and Stonehenge (Britain, c. 3000 BCE) reveal religious and astronomical dimensions of early construction. Mudbrick and timber structures characterized early agrarian settlements in Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indus Valley, and China.

- Mesopotamia saw the rise of ziggurats—stepped temples made of baked brick, elevated to commune with the divine.

- Ancient Egypt perfected stone masonry with pyramids and temples aligned to solar and cosmic principles.

- The Indus Valley Civilization displayed advanced urban planning: grid layouts, sewage systems, and standardized bricks.

- Early Chinese architecture was wooden, emphasizing symmetry, axial alignment, and integration with landscape.

2.2 Classical and Imperial Architecture

In the ancient Mediterranean, architecture became a language of empire, philosophy, and proportion.

- Greek architecture emphasized harmony, ideal ratios, and public life. Temples like the Parthenon exemplified clarity and mathematical beauty.

- Roman architecture introduced the arch, vault, and concrete, enabling vast public works: aqueducts, amphitheaters, and domes like the Pantheon.

- In Persia and India, monumental palaces, stepped wells, and stupa-temples integrated regional styles with imperial symbolism.

- Pre-Columbian Americas (Maya, Inca, Aztec) built pyramids, ceremonial plazas, and urban complexes aligned to celestial patterns and terrain.

2.3 Medieval and Religious Architecture

The medieval era saw the flourishing of religious architecture: cathedrals, mosques, monasteries, and temples.

- Gothic cathedrals in Europe—like Chartres and Notre-Dame—used pointed arches and flying buttresses to reach toward heaven.

- Islamic architecture spanned from Spain to India, showcasing domes, courtyards, minarets, and intricate arabesques, exemplified in structures like the Alhambra and Taj Mahal.

- East Asian architecture matured into grand wooden complexes, such as the Forbidden City and Kyoto temples, emphasizing hierarchy, nature, and ritual space.

- In Sub-Saharan Africa, unique traditions emerged, such as the mud mosques of Timbuktu and Great Zimbabwe’s stone enclosures.

2.4 Renaissance to Enlightenment: The Rise of the Architect

The Renaissance revived classical ideals with new humanist and scientific vision. Architecture became both a learned profession and an intellectual pursuit.

- Brunelleschi’s dome in Florence and Palladio’s villas in Italy symbolized balance, geometry, and proportion.

- The Baroque style in Catholic Europe emphasized grandeur, emotion, and movement, as in Versailles and St. Peter’s Basilica.

- The Enlightenment introduced neoclassicism: clean lines, civic ideals, and rational structure, reflected in American capitols and European courts.

2.5 Industrial Age and Modernism

The 19th century brought new materials—iron, steel, glass—and urban transformation.

- Train stations, bridges, and exhibition halls—like the Eiffel Tower or Crystal Palace—exhibited industrial aesthetics.

- In the early 20th century, Modernist architects like Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and Frank Lloyd Wright redefined architecture as functional, minimalist, and technologically oriented.

- Movements like Bauhaus and International Style sought universality, rejecting ornament in favor of efficiency and form.

2.6 Postmodernism, Deconstruction, and Beyond

Post-WWII architecture fractured into diverse schools:

- Postmodernism revived symbolism and historical reference with playful, eclectic forms.

- Deconstructivism embraced asymmetry, fragmentation, and conceptual abstraction, as seen in works by Gehry or Hadid.

- In the Global South, vernacular revival and regional modernism emerged—adapting local materials and climate-conscious design to modern needs.

2.7 Contemporary Trends and the Green Revolution

Today, architecture is global, digital, and ecological.

- Parametric design and digital modeling allow complex, fluid forms.

- Biophilic design and green building standards (like LEED) integrate nature, light, and energy efficiency.

- Architects now consider carbon footprints, urban heat islands, social equity, and psychological well-being.

- The shift toward sustainable, human-centered design marks a profound return to architecture as a life-integrating art and science.

3. A History of Gardens and Landscaping

Gardens and landscaped spaces are among humanity’s oldest and most enduring expressions of the desire to live in harmony with nature. More than decoration, gardens are places of meaning—sacred groves, spaces for contemplation, sources of sustenance, and manifestations of order, beauty, and power. Landscaping as an art and science reflects changing relationships between humans and the environment: from taming wildness to mimicking it, from demonstrating wealth to fostering ecological balance.

3.1 Early Horticulture and Sacred Landscapes

In early civilizations, landscaping emerged in tandem with agriculture and religion.

- In Mesopotamia, kings built enclosed gardens with fruit trees, shade, and irrigation—mythologized in the idea of Eden.

- Ancient Egyptian temples and palaces were flanked by symmetrical gardens with date palms, lotus ponds, and canals—linked to rituals and cosmic order.

- In Persia, the chahar bagh (“four-part garden”) design symbolized paradise: a quadrilateral space divided by water channels, shaded and walled—a model that would influence Islamic, Indian, and Western gardens for centuries.

3.2 Classical and Imperial Gardens

- In Greece and Rome, gardens were spaces of leisure and learning. Roman villas featured peristyle gardens, fountains, and statuary—both private retreats and public status symbols.

- Chinese gardens, evolving from as early as the Shang Dynasty, emphasized philosophical naturalism. Rather than geometric precision, they used rockeries, asymmetrical paths, pavilions, and borrowed scenery to evoke harmony with Dao.

- Japanese gardens developed Zen minimalism and symbolic arrangements—sand raked to represent water, stones as mountains—creating contemplative microcosms.

3.3 Monastic and Islamic Garden Traditions

- Christian monasteries in medieval Europe cultivated cloister gardens for both spiritual reflection and medicinal herbs. These were ordered and enclosed, representing spiritual order amid chaos.

- Islamic gardens, from Andalusia to Mughal India, refined the Persian model. The Alhambra’s Generalife and the Taj Mahal’s gardens embody a paradisiacal ideal: water, fragrance, color, and symmetry symbolizing divine balance.

3.4 Renaissance and Baroque Landscaping

- The Italian Renaissance introduced geometrical precision, axial symmetry, and terraces, as seen in the Villa d’Este and Boboli Gardens.

- The French formal garden under André Le Nôtre (e.g., Versailles) became the height of absolutist grandeur—long vistas, parterres, reflecting pools, and mastery over nature.

- In contrast, English landscape gardens (18th century) emphasized pastoral naturalism, inspired by Romanticism and classical paintings. Rolling lawns, artificial ruins, and serpentine lakes replaced rigid geometry.

3.5 Colonial and Botanical Gardens

As European empires expanded, so too did horticultural exploration.

- Botanical gardens, like those at Kew and Calcutta, served as centers of scientific classification, imperial trade, and ecological collection.

- Colonial estates often imposed European landscaping styles on tropical environments, introducing alien species and reshaping local ecologies.

3.6 20th Century to Present: Public Parks and Ecological Design

- The urban parks movement, led by figures like Frederick Law Olmsted (Central Park), democratized green space and integrated landscape into the city.

- The 20th century saw the rise of landscape architecture as a formal profession—balancing art, ecology, and urban planning.

- In recent decades, the field has shifted toward sustainable landscaping, restorative ecology, and permaculture. Xeriscaping, native planting, and green infrastructure (rain gardens, bioswales, green roofs) are now central strategies.

- Contemporary landscape designers often work across disciplines—designing for biodiversity, carbon sequestration, mental health, and community resilience.

From sacred groves to smart parks, landscaping has never been merely ornamental. It is a language by which societies communicate their relationship with nature, health, and one another. As climate pressures mount and urban density rises, the role of gardens and green infrastructure is becoming central to the well-being of both people and planet.

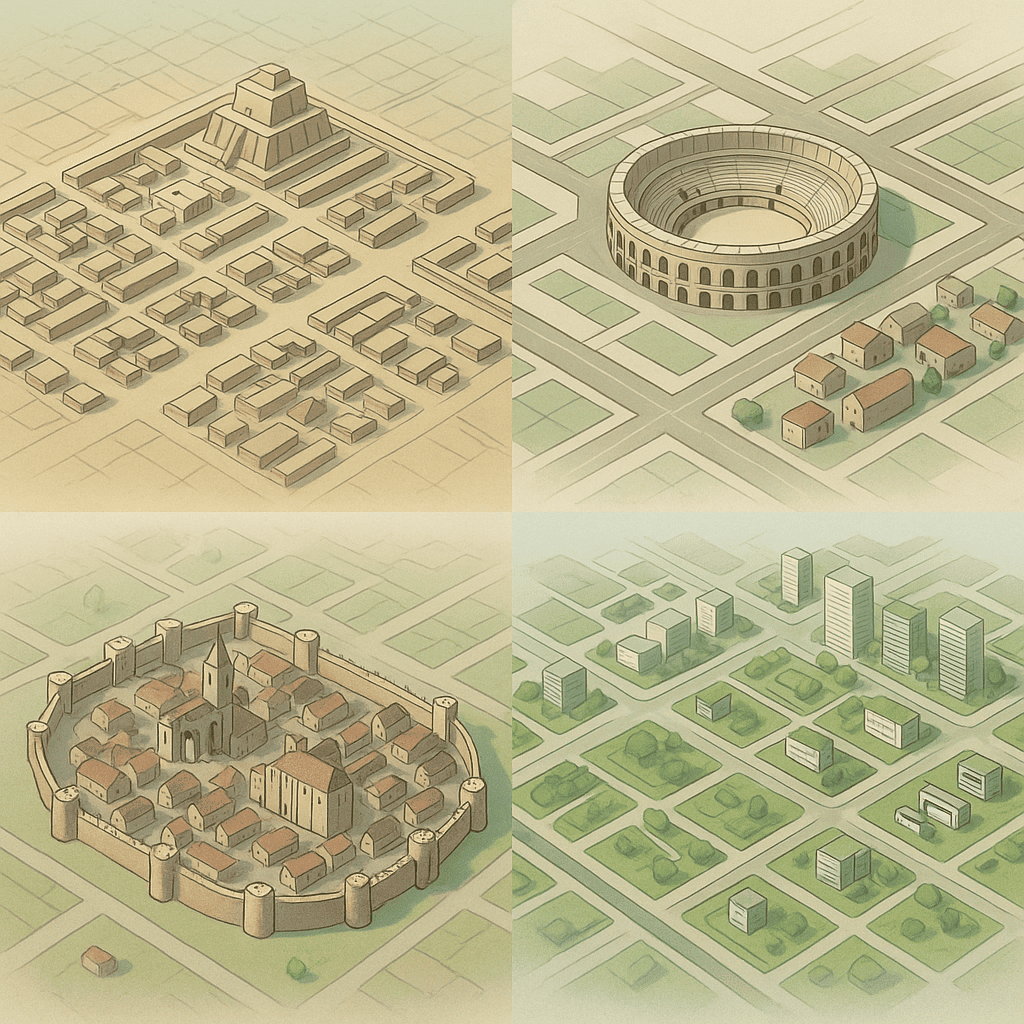

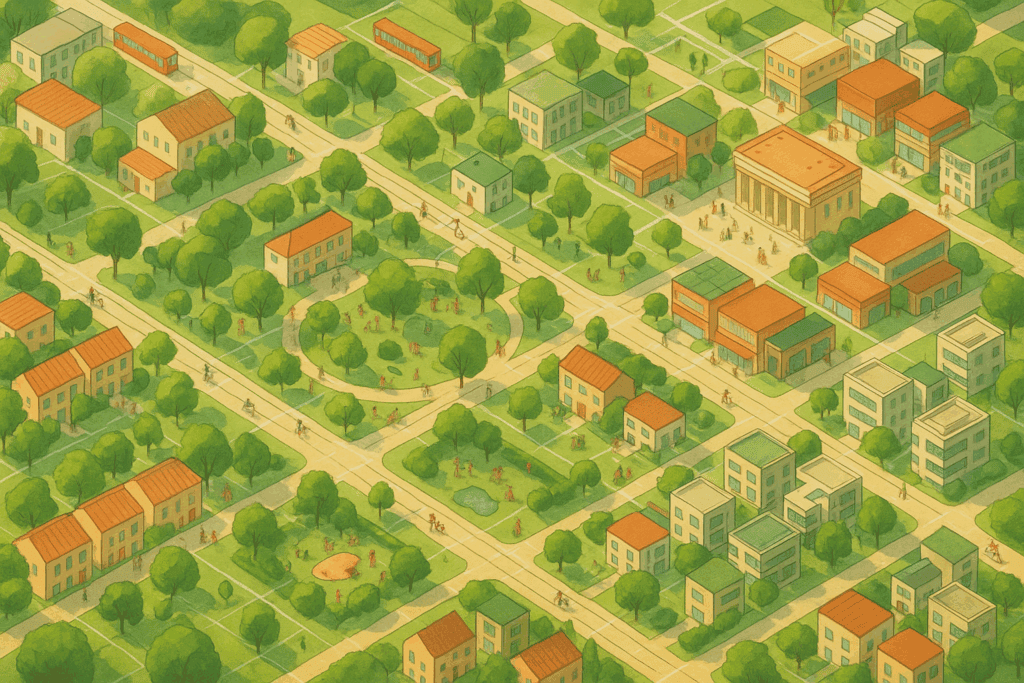

4. The Evolution of City Planning

City planning is the conscious design and organization of urban space—its streets, buildings, infrastructure, and public realms. It shapes how people live, move, work, govern, and relate to one another. At its best, city planning expresses a society’s highest ideals; at its worst, it can enforce segregation, inefficiency, or environmental destruction. The history of city planning is a record of human experimentation in how to live together at scale.

4.1 Early Urbanism: Order and Ritual

The first cities emerged independently in several regions around the world—Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, Egypt, Mesoamerica, and China—each reflecting spiritual, political, and practical aims.

- Mesopotamian cities like Ur were structured around ziggurats and walled precincts, combining temples, granaries, and markets.

- The Indus Valley cities, including Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, had remarkably modern features: gridded streets, drainage systems, standardized construction, and public bathing areas.

- In ancient China, the Zhou and Han dynasties developed walled, rectangular cities with cardinal alignment and hierarchical spatial order.

- In Mesoamerica, cities like Teotihuacan and Tikal featured monumental ceremonial centers oriented to celestial events.

4.2 Classical Cities: Polis and Empire

- Greek city-states (poleis) were built around agora (public squares), temples, and gymnasia. The urban form emphasized civic life, walkability, and human scale.

- Roman urbanism introduced the military grid, paved roads, aqueducts, amphitheaters, and sewers across a vast empire. The Roman cardo and decumanus (main north-south and east-west streets) influenced city layouts for centuries.

- Byzantine and Islamic planners adopted and adapted Roman forms—incorporating mosques, caravanserais, and labyrinthine souqs into compact walled cities.

4.3 Medieval and Renaissance Urban Forms

- Medieval European towns grew organically—winding streets, fortified walls, and feudal precincts. They reflected defense concerns and trade-based evolution rather than central design.

- With the Renaissance, urban design returned to classical principles: symmetry, piazzas, axial streets. Ideal city plans were proposed by theorists like Alberti and Leonardo da Vinci.

- Baroque planning introduced dramatic axes, grand boulevards, and visual focal points—epitomized by Rome’s papal city and Paris under Haussmann.

4.4 Industrialization and the Modern City

The 19th century brought rapid urban growth, often chaotic and unhealthy.

- Cities swelled with migrant labor, leading to overcrowding, pollution, and slums.

- Reformers like Ebenezer Howard proposed the Garden City: small, planned communities integrating nature and industry, aiming for social harmony.

- Haussmann’s redesign of Paris introduced broad avenues, sewer systems, and zoning to tame medieval chaos into modern order.

- In the United States, grid plans (like New York’s 1811 Commissioners’ Plan) became standard, prioritizing efficiency over topography or culture.

4.5 20th Century Planning Theories and Movements

- Le Corbusier envisioned the “Radiant City”: towers in a park, efficient but criticized for alienating human scale and local context.

- Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City countered with decentralized, automobile-based suburbanism.

- Modernist planning often prioritized roads, zoning, and uniformity—leading to functional but sometimes soulless environments.

- The postmodern reaction brought complexity, diversity, and historicism back to planning discourse.

4.6 Contemporary and Future Planning Trends

Today, city planning is a hybrid of disciplines—blending urban design, environmental science, data analytics, sociology, and public policy.

- Smart cities use sensors and algorithms to optimize traffic, energy use, and security.

- New Urbanism promotes walkability, mixed-use zoning, and community-centered design.

- Transit-oriented development (TOD) focuses on reducing car dependence through rail, cycling, and pedestrian infrastructure.

- Resilience planning addresses climate change, flood control, migration, and social equity.

- Participatory planning invites community input and empowerment, especially among historically marginalized groups.

4.7 Nusantara: A Case Study in Planned Futures

Indonesia’s planned new capital, Nusantara, on the island of Borneo, reflects many of these contemporary concerns.

- Purpose: Jakarta, overcrowded and sinking, can no longer serve as an effective capital. Nusantara aims to be sustainable, decentralized, and futuristic.

- Design: The city is envisioned as green, smart, and low-carbon, integrating forests, renewable energy, and indigenous culture into urban space.

- Comparison with Jakarta: Jakarta suffers from traffic, pollution, flooding, and sprawl. Nusantara’s plan seeks to start anew—with better land use, water management, and mobility.

- Global Comparisons: Similar efforts include Brasília (Brazil), Putrajaya (Malaysia), and Naypyidaw (Myanmar). Each has faced challenges in culture, governance, and social integration—offering both warnings and lessons.

From ancient grid cities to AI-driven eco-capitals, city planning reflects both the dreams and dilemmas of civilization. Its evolution reveals a growing understanding: that a city is not just a machine or market, but a living system—of people, places, and planet.

5. Science and Spirituality in Design – Feng Shui and Other Geomantic Traditions

Before modern urban planning and environmental science, ancient cultures around the world developed intuitive systems to understand how landscapes, structures, and cosmic forces interact. These systems, known broadly as geomancy—earth divination—blend environmental observation with spiritual philosophy. Among the most enduring and influential of these is Feng Shui, the Chinese art and science of spatial harmony. Though often misunderstood as superstition, many principles of geomantic traditions reflect sophisticated ecological reasoning and psychophysical insight.

5.1 Origins and Principles of Feng Shui

Feng Shui (風水), literally “wind and water,” is an ancient Chinese practice concerned with the flow of qi (energy) through space. Rooted in Daoist cosmology, Feng Shui seeks to balance the forces of Yin and Yang, and harmonize the Five Elements (Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, Water) within a given site or structure.

Key traditional concepts include:

- Orientation: Aligning buildings with cardinal directions, typically facing south for sunlight and warmth.

- Topography: Favorable sites are backed by mountains (protection), fronted by water (abundance), and open to gentle breezes (vital energy).

- Bagua Map: A symbolic octagonal grid used to analyze spatial energy and guide layout decisions.

- Flow and blockage: Avoiding sharp angles, narrow corridors, and obstructed entrances that can “cut” or stagnate qi.

Historically, Feng Shui was applied in the planning of imperial capitals (e.g., Beijing), tomb sites, temples, and homes. It was practiced by learned consultants with astronomical knowledge and geomantic compasses (luopan), and often required extensive environmental surveys.

5.2 Scientific Perspectives on Feng Shui

Modern interpretations of Feng Shui range from skeptical dismissal to symbolic reinterpretation. Some of its principles overlap with empirical findings in environmental psychology, architecture, and sustainability:

- Orientation and light: The southern exposure recommended by Feng Shui corresponds with optimal passive solar design.

- Natural features and ventilation: Good topography and airflow are essential to comfort, climate control, and disease prevention.

- Clutter and spatial flow: Research on mental health and productivity supports the idea that spatial openness, cleanliness, and intuitive flow enhance well-being.

- Biophilia: The use of water features, natural materials, and plants aligns with the modern concept of biophilic design, which emphasizes human connection with nature.

While the metaphysical framework of qi cannot be empirically measured, the holistic, site-sensitive mindset of Feng Shui offers valuable insight into human-environment interaction.

5.3 Geomantic Traditions Around the World

Other cultures developed comparable practices, often blending cosmology, religion, and ecology:

- Vāstu Shastra (India): An ancient Hindu system of architecture prescribing sacred geometry, orientation, and spatial arrangement based on the movements of planets and deities. Like Feng Shui, it values symmetry, balance, and site-specificity.

- Native American geomancy: Many Indigenous peoples in the Americas oriented homes, sacred structures, and cities according to solar cycles, cardinal directions, and spiritual beliefs. The Ancestral Puebloans’ Chaco Canyon aligns with solstices and equinoxes.

- Islamic urbanism: Islamic cities often aligned their mosques toward Mecca (the qibla) and used geometry to harmonize spiritual and civic space.

- Medieval European orientation: Churches were commonly built with altars facing east (toward the rising sun), symbolizing resurrection and divine light.

5.4 Integrating Ancient Wisdom with Modern Design

Rather than dismissing geomantic traditions as obsolete, contemporary designers increasingly explore their symbolic and environmental value. In sustainable architecture, urban ecology, and therapeutic design, planners often rediscover the importance of:

- Site analysis before construction

- Integration with local climate and natural features

- Orientation to solar and seasonal cycles

- Holistic thinking about space, mind, and community

Some architects and city planners now collaborate with cultural experts or revive traditional spatial languages to reconnect built environments with cultural memory and environmental wisdom.

Conclusion:

While modern science provides powerful tools for measuring and building, ancient geomantic systems remind us that the meaning of place also matters. Design is not just a question of function or efficiency, but of spirit, balance, and relationship with the world. In the convergence of science and spirituality, we find a deeper architecture—one that aims not only to shelter life, but to elevate it.

6. Principles of Architectural Design and Construction

Architecture is where imagination meets engineering, where cultural expression takes physical form. The design and construction of buildings must reconcile the abstract ideals of beauty and function with the concrete demands of physics, climate, materials, and human need. Whether designing a humble house or a grand civic complex, architects and builders work with a shared set of principles that guide the transformation of space into shelter, symbol, and system.

6.1 Vitruvian Foundations: Firmitas, Utilitas, Venustas

The Roman architect Vitruvius, in the 1st century BCE, articulated three enduring principles of good architecture:

- Firmitas – Strength: A building must be structurally sound and durable.

- Utilitas – Utility: It must serve its intended purpose efficiently and comfortably.

- Venustas – Beauty: It should offer aesthetic pleasure and emotional resonance.

These ideals remain foundational, though they are now supplemented by environmental, psychological, and technological considerations.

6.2 Core Principles of Design

Modern architecture balances creative freedom with functional precision through key design elements:

- Function and Program: Every space must suit its use—residential, institutional, commercial, sacred, etc. Function determines layout, flow, and proportion.

- Form and Space: Architects manipulate shape, volume, and void to create harmonious spatial experiences. Negative space (open areas) is as important as walls.

- Light and Shadow: Natural light enhances mood, health, and energy efficiency. Openings, skylights, shading, and orientation are carefully calibrated.

- Materials: The palette of stone, brick, wood, metal, glass, and composites influences not only strength and insulation but emotional tone and cultural meaning.

- Rhythm and Scale: Repetition, variation, and proportion guide how spaces feel—whether monumental or intimate.

- Context and Site: A building must respond to its location—climate, landscape, neighborhood, and history.

6.3 Construction Principles

Building is a multidisciplinary process requiring coordination among architects, engineers, contractors, and tradespeople. Key principles include:

- Structural Systems: Beams, columns, load-bearing walls, and trusses must efficiently distribute forces—gravity, wind, seismic stress—without failure.

- Foundation and Groundwork: Stable foundations depend on soil testing, drainage planning, and site grading. Mistakes here jeopardize everything above.

- Building Envelope: Walls, roofs, doors, and windows protect the interior from the elements while allowing light, ventilation, and insulation.

- Thermal and Moisture Control: Proper sealing, vapor barriers, and insulation are vital for energy efficiency and longevity.

- Mechanical Systems: Plumbing, electricity, HVAC, elevators, and fire safety systems must be integrated without disrupting design integrity.

- Construction Management: Timelines, budgets, materials logistics, workforce coordination, and safety are tightly regulated to ensure project success.

6.4 Architectural Styles and Philosophies

Throughout history, different design philosophies have shaped how these principles are applied:

- Classical and Renaissance architecture emphasized symmetry, order, and ideal proportion.

- Modernism championed minimalism, function, and technological expression.

- Postmodernism reintroduced ornament, irony, and context sensitivity.

- High-tech and parametric architecture use digital modeling to create fluid, futuristic forms.

- Vernacular and regionalist architecture adapt traditional styles to modern contexts using local materials and climate wisdom.

- Green and biophilic design integrates architecture with ecosystems, daylighting, natural ventilation, and plant life.

6.5 The Role of the Architect

An architect today must be both artist and analyst, scientist and storyteller. Responsibilities include:

- Site and user analysis

- Conceptual design and visualization

- Technical drawings and blueprints

- Building code compliance and permitting

- Coordination with engineers and specialists

- Oversight of construction quality

Licensure, ethics, and continuing education are essential to uphold public safety, environmental responsibility, and cultural value.

Conclusion:

Architecture is the most public of the arts and the most personal of the sciences. It must protect life while also giving it form, spirit, and meaning. By mastering principles of structure, aesthetics, context, and sustainability, architecture becomes more than building—it becomes civilization made visible.

7. Principles of Gardening and Landscaping

Gardening and landscaping are the living arts of shaping land, water, flora, and space into environments of beauty, utility, and ecological function. Whether designing a private garden, a public park, or a landscape around a city plaza, the fundamental goal is to harmonize the built and natural worlds. This practice draws from horticulture, aesthetics, soil science, and environmental design, requiring sensitivity to climate, scale, and life itself.

7.1 The Function of Landscapes

Landscaping is not merely decorative—it serves diverse purposes:

- Ecological: Enhances biodiversity, pollination, and soil health; mitigates erosion, flooding, and pollution.

- Aesthetic: Shapes emotional experience, visual rhythm, and seasonal beauty.

- Functional: Defines space for walking, sitting, playing, gardening, and gathering.

- Social and cultural: Conveys identity, tradition, and community values.

- Environmental regulation: Controls microclimate through shade, humidity, wind buffering, and cooling via evapotranspiration.

7.2 Key Principles of Garden and Landscape Design

While styles vary greatly—from formal French gardens to wild prairie meadows—successful designs are grounded in a shared design language:

1. Unity and Harmony

- Design elements—plants, paths, structures—should work together to create a cohesive whole.

- Themes, color palettes, and recurring shapes enhance continuity and mood.

2. Balance and Proportion

- Visual balance can be symmetrical or asymmetrical, but should feel stable and intentional.

- Plants and features should be scaled appropriately to the space and each other.

3. Rhythm and Repetition

- Patterns of planting or placement guide the eye and create movement across the landscape.

- Repeated motifs—rows of trees, matching benches, or flowering beds—foster a sense of order.

4. Focal Points and Flow

- Every landscape needs focal areas: a sculpture, a pond, a vibrant tree. These draw attention and give identity to the space.

- Pathways, sightlines, and terrain guide the flow of visitors and visual attention.

5. Texture and Contrast

- Texture is the tactile and visual feel of foliage, bark, stone, or mulch.

- Contrast between smooth and rough, fine and bold, dark and bright, enlivens the composition.

7.3 The Living Medium: Soil, Water, and Plants

At its heart, landscaping works with living systems. Mastery of plant science and land management is essential.

- Soil: Must be evaluated for structure, drainage, pH, and nutrients. Composting and amending are often necessary.

- Water: Efficient irrigation systems (drip lines, rainwater harvesting) reduce waste. Plant selection must match water availability.

- Climate and Zone: Every plant thrives in a specific temperature and humidity range. Knowledge of hardiness zones and microclimates is key.

- Native and Adaptive Plants: Favoring native or low-maintenance species encourages resilience, reduces chemical use, and supports local ecosystems.

7.4 Sustainable and Ecological Landscaping

The rise of environmental consciousness has redefined best practices:

- Xeriscaping: Low-water landscaping using drought-tolerant plants, rock features, and strategic shade.

- Rain gardens and bioswales: Manage stormwater runoff and filter pollutants.

- Edible landscaping: Integrates fruits, herbs, and vegetables into aesthetic designs.

- Rewilding and pollinator gardens: Restore habitat and biodiversity in urban and suburban spaces.

7.5 The Landscape Designer’s Role

Landscape designers and architects integrate artistry with technical knowledge:

- Site analysis: elevation, drainage, sun and wind patterns

- Design planning and drafting (often using CAD software or hand renderings)

- Knowledge of plant biology and garden maintenance

- Collaboration with urban planners, civil engineers, and horticulturalists

Good landscaping is dynamic—it matures, evolves, and interacts with time. It is a partnership with nature, not just an imprint upon it.

Conclusion:

Gardens and landscapes speak the silent language of living systems shaped by human hands. When guided by thoughtful design and ecological awareness, they become sanctuaries of health, beauty, and connection—links between earth and art, between past and future, between human and habitat.

8. Principles of City Planning

City planning—also known as urban planning—is the art and science of organizing land use, infrastructure, and public life within human settlements. At its best, it creates inclusive, functional, sustainable, and inspiring environments where people can thrive. At its worst, it can reinforce inequality, congestion, and environmental degradation. The principles of effective city planning draw from geography, sociology, architecture, ecology, engineering, economics, and democratic governance.

8.1 Fundamental Goals of City Planning

Every city is a response to a set of core needs:

- Habitability: Provide safe, comfortable housing and public amenities.

- Mobility: Ensure people can move efficiently—by foot, bike, car, or transit.

- Economic vitality: Enable commerce, innovation, and equitable opportunity.

- Cultural identity: Reflect the heritage and values of its inhabitants.

- Environmental stewardship: Work in harmony with natural systems.

- Social equity: Guarantee access to services and participation in planning processes for all citizens.

A well-planned city is not simply efficient; it is just, adaptive, and enriching.

8.2 Core Elements of Urban Design

1. Land Use Planning

- Zoning: Divides land into categories such as residential, commercial, industrial, agricultural, or mixed-use.

- Density: Controls how many people or buildings are allowed in an area; higher density supports walkability and public transit.

- Use mixing: Promotes diversity of functions within close proximity to reduce commute times and foster vibrancy.

2. Transportation and Circulation

- Street hierarchy: Organizes roads by type (arterial, collector, local) to distribute traffic efficiently.

- Transit networks: Includes buses, trains, subways, and emerging mobility services.

- Walkability and bikeability: Sidewalks, crosswalks, bike lanes, and pedestrian-friendly blocks encourage healthier, more connected cities.

- Accessibility: Designs must accommodate children, elderly, and people with disabilities.

3. Infrastructure and Utilities

- Clean water supply, sewage systems, waste management, power grids, and telecommunications are the unseen skeleton of urban life.

- Resilient infrastructure includes redundancy, decentralization, and adaptability to climate change and disasters.

4. Public Space and Community Life

- Parks, plazas, libraries, schools, and markets are the social heart of a city.

- Urban planners aim to create “third places” beyond home and work where people meet and build community.

5. Housing and Affordability

- Balanced housing strategies must include a mix of market-rate, subsidized, and community-owned options to prevent segregation and gentrification.

- Inclusionary zoning and rent controls are tools for equity.

8.3 The Planning Process

City planning typically unfolds in several phases:

- Data Collection and Analysis: Demographics, traffic patterns, land use, environmental studies, and historical context.

- Visioning and Consultation: Stakeholder engagement, public meetings, and participatory design processes.

- Drafting the Plan: Land use maps, development codes, transportation models, and regulatory guidelines.

- Implementation: Phased development, permitting, construction, and investment incentives.

- Review and Revision: Periodic updates to adapt to shifting needs and emerging challenges.

8.4 Models and Theories in Urban Planning

Over the past century, urban planners have proposed various paradigms:

- The Garden City (Ebenezer Howard): Combines urban and rural ideals in self-contained, green-ringed communities.

- The Radiant City (Le Corbusier): Emphasizes towers, efficiency, and separation of functions.

- New Urbanism: Seeks to revive traditional town layouts with walkability, mixed-use cores, and transit focus.

- Transit-Oriented Development (TOD): Builds dense, livable communities around transit hubs to reduce car dependency.

- Smart Growth: Aims to limit sprawl, preserve open space, and redevelop existing urban areas.

- Resilience and Regenerative Planning: Focuses on ecological integration, disaster preparedness, and system feedback.

8.5 Challenges in City Planning

Contemporary cities face mounting complexities:

- Climate change: Rising sea levels, heat waves, and extreme weather demand adaptive urban strategies.

- Resource limits: Water, energy, and food security must be planned at the metropolitan scale.

- Inequality and exclusion: Marginalized communities often face displacement, poor services, and planning neglect.

- Data and surveillance: Smart technologies pose both opportunities for efficiency and risks to privacy and democracy.

Planners must balance competing interests: short-term profits vs. long-term livability, private development vs. public good, innovation vs. tradition.

Conclusion:

City planning is the act of shaping collective destiny in space. It requires foresight, compassion, evidence, and imagination. In building cities, we are not merely arranging streets and utilities—we are deciding how people will live, relate, dream, and grow. The future of humanity is, in large part, a question of how wisely and justly we plan the cities we call home.

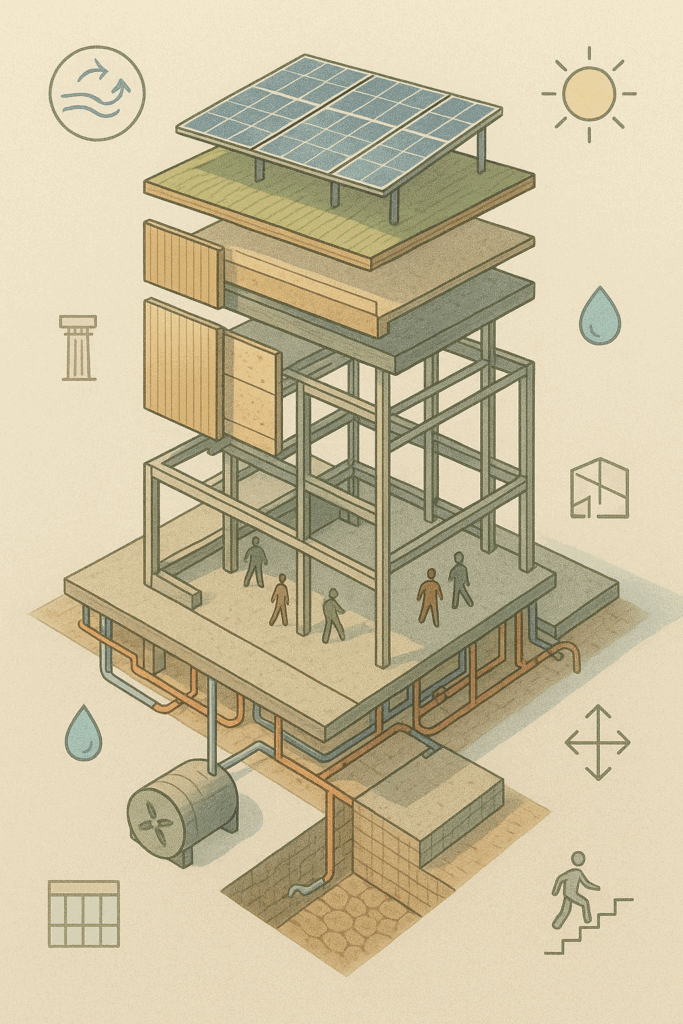

9. The Science and Technology of Building and Planning

Architecture, landscaping, and city planning may begin with vision and art, but they are ultimately realized through science and technology. From foundational physics to cutting-edge digital modeling, successful design depends on the mastery of materials, forces, systems, and data. Every structure, garden, and city is an applied experiment—balancing creativity with constraints, and translating abstract plans into safe, durable, and sustainable environments.

9.1 Structural Mathematics and Engineering Principles

Understanding forces—tension, compression, torsion, and shear—is essential to any construction:

- Statics and dynamics govern how loads (dead loads, live loads, wind, seismic) are distributed across structures.

- Structural systems include post-and-lintel, arches and vaults, trusses, frames, and shell structures.

- Computational modeling now allows real-time stress analysis and optimization, reducing material use while increasing strength.

From the angle of a roof to the depth of a foundation, calculations ensure safety and longevity.

9.2 Material Science and Innovation

Every material has distinct properties of strength, weight, flexibility, insulation, cost, and environmental impact.

- Traditional materials: Wood, stone, brick, clay, lime, and thatch—still valued for local adaptation and carbon sequestration.

- Modern materials: Steel, reinforced concrete, glass, aluminum—allow for bold spans and tall buildings.

- Advanced materials: Cross-laminated timber (CLT), self-healing concrete, phase-change materials, and nanocoatings promise new efficiencies.

- Sustainable materials: Bamboo, rammed earth, recycled composites, and bioplastics reduce environmental costs.

Material choice is also cultural and aesthetic—defining how a space feels and ages.

9.3 Systems Integration in Buildings and Landscapes

The comfort, efficiency, and safety of any built environment depend on the seamless integration of key systems:

- Water systems: Plumbing, graywater recycling, stormwater management, irrigation, and flood resilience.

- Energy systems: Electrical wiring, renewable energy (solar, wind, geothermal), passive heating and cooling, and battery storage.

- HVAC systems: Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning require careful planning for energy efficiency and indoor air quality.

- Lighting systems: Use of LEDs, sensors, daylight harvesting, and programmable interfaces.

- Safety systems: Fire suppression, alarm systems, structural redundancy, and seismic retrofitting.

- Waste systems: Solid waste separation, composting, bioswales, and vacuum waste networks in advanced cities.

In green architecture, these systems are increasingly designed for regenerative performance—producing more energy or clean water than they consume.

9.4 Site Analysis and Environmental Technology

Before any construction, a thorough analysis of the site is essential:

- Topographic surveys and geotechnical analysis determine soil strength, slope, and drainage.

- Climatic data guides orientation, shading, and ventilation strategies.

- GIS (Geographic Information Systems) allow planners to overlay demographic, ecological, and infrastructure data at multiple scales.

- Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) evaluate effects on biodiversity, water, air, and cultural heritage.

New tools include drones for surveying, LiDAR for terrain mapping, and digital twins—virtual city models updated in real time.

9.5 Digital Technologies in Design and Construction

- CAD (Computer-Aided Design) and BIM (Building Information Modeling) enable 3D modeling, structural coordination, and cost estimation.

- Parametric design allows architects to use algorithms to optimize shape, material use, and energy performance.

- 3D printing and modular construction allow for faster, cheaper, and more customized building processes.

- Smart sensors and IoT (Internet of Things) in buildings and cities monitor temperature, traffic, air quality, and user behavior—informing maintenance and policy.

Technology is not only transforming how we build, but how we live in buildings—creating responsive, adaptive, and participatory spaces.

Conclusion:

The science of building and planning is as complex and evolving as the environments we create. Behind every well-designed space is an intricate dance of physics, data, biology, and machines—each decision influencing quality of life and planetary health. Mastery of these systems does not replace artistry; it empowers it. With the right tools, we can design places that are not only structurally sound but socially and ecologically intelligent.

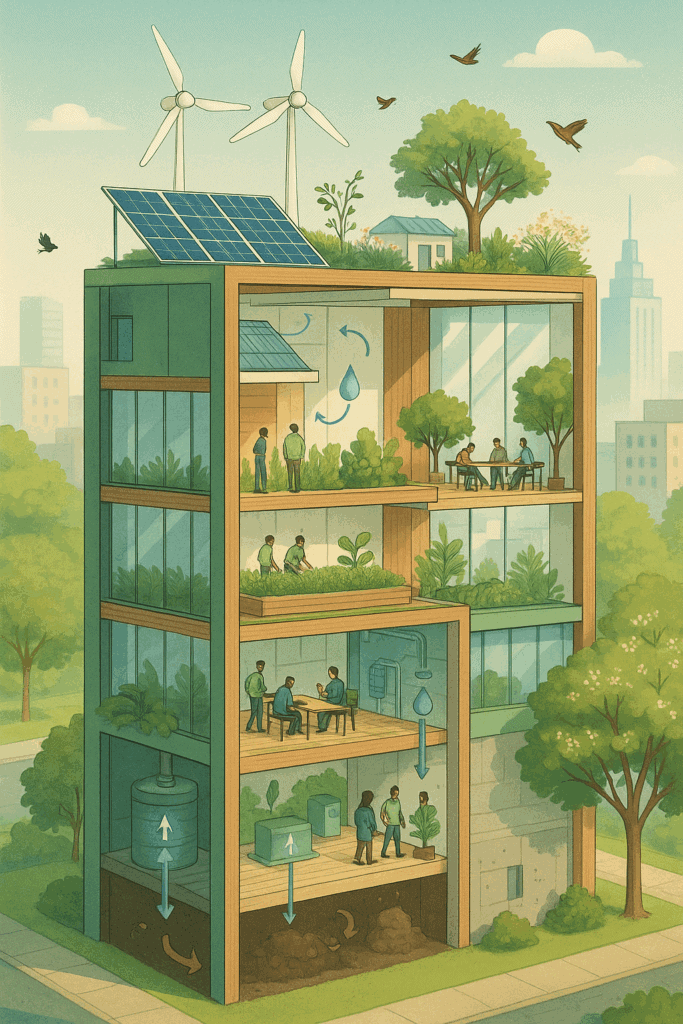

10. Sustainable and Green Design

As humanity confronts the environmental costs of urbanization, construction, and consumption, a new paradigm has emerged: sustainable and green design. No longer an optional add-on, ecological responsibility is now a central pillar of architecture, landscaping, and city planning. The goal is not just to minimize harm, but to design regenerative systems—built environments that support life, conserve resources, and heal the planet.

10.1 The Environmental Cost of the Built World

Globally, the construction and operation of buildings account for:

- Nearly 40% of energy consumption

- Over 30% of CO₂ emissions

- Significant extraction of water, minerals, metals, and timber

Urban heat islands, deforestation, habitat loss, and stormwater runoff are just a few of the unintended consequences of traditional design and planning. Sustainable design addresses these impacts at their source.

10.2 Principles of Sustainable Design

Sustainability begins with core principles:

- Resource Efficiency: Use fewer materials, less energy, and less water throughout a building’s lifecycle.

- Passive Design: Rely on natural ventilation, lighting, and thermal mass to reduce mechanical systems.

- Lifecycle Thinking: Assess environmental impact from construction to demolition—including materials sourcing, transportation, use, and disposal.

- Adaptability and Longevity: Design for future reuse, retrofitting, and evolving needs.

- Biodiversity and Ecology: Incorporate native plants, wildlife corridors, pollinator habitats, and green roofs.

The mantra of green design is: Reduce, Reuse, Regenerate.

10.3 Green Architecture Innovations

Modern architects now integrate sustainability into the very DNA of their designs:

- Green roofs and living walls: Reduce heat, manage stormwater, and insulate buildings.

- Solar orientation and thermal mass: Buildings are aligned and constructed to naturally regulate temperature.

- High-performance glazing and insulation: Improve energy efficiency while allowing natural light.

- Renewable energy integration: Photovoltaics, geothermal systems, wind turbines, and battery storage are increasingly standard.

- Smart controls: Sensors and automation regulate lighting, climate, and water use based on real-time needs.

Certifications such as LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) and BREEAM (Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method) now guide global standards in green building.

10.4 Sustainable Landscaping and Urban Ecology

The principles of ecological design extend into parks, gardens, and entire urban ecosystems:

- Permaculture: Designs landscapes to mimic natural systems—integrating food production, water management, and biodiversity.

- Xeriscaping: Uses drought-tolerant plants and efficient irrigation to minimize water use.

- Bioswales and rain gardens: Channel and purify stormwater while beautifying the landscape.

- Green corridors: Link parks, tree-lined streets, and undeveloped land to preserve urban wildlife and improve air quality.

Urban greening improves not only ecological health but also human well-being—reducing stress, enhancing property values, and cooling cities.

10.5 Sustainable Cities and Planning Models

On a larger scale, sustainability demands rethinking the entire urban organism:

- 15-Minute Cities: Every essential need—work, school, groceries, recreation—is accessible within a short walk or bike ride.

- Transit-Oriented Development (TOD): Reduces car dependency by concentrating development around public transit nodes.

- Eco-cities: Purpose-built sustainable cities such as Masdar City (UAE), Songdo (South Korea), and the planned Nusantara (Indonesia) aim to model climate-conscious futures.

- Circular urbanism: Treats cities like living systems where waste becomes input—closing loops in food, water, and energy systems.

10.6 Human-Centered and Regenerative Design

Green design is not only about metrics—it’s about quality of life:

- Biophilic design: Integrates nature into interiors and public space, supporting mental health and productivity.

- Thermal and acoustic comfort, air quality, daylight exposure, and social interaction are prioritized in human-centered design.

- Regenerative design: Goes beyond reducing harm to actively healing environments—replenishing water tables, restoring topsoil, and increasing carbon capture.

Conclusion:

Green design is the bridge between civilization and ecology. It asks us not just to build better, but to live better—within our means, in cooperation with the Earth, and in recognition that our built world is inseparable from the biosphere. The most sustainable building is not one that harms less, but one that helps more.

11. Economics, Policy, and Governance of Living Spaces

Designing and constructing homes, cities, and landscapes is not just a technical or artistic endeavor—it is fundamentally political and economic. Who decides what gets built, where, for whom, and at what cost? What rules guide these decisions? The economics and governance of living spaces affect everything from access to housing and public services to environmental justice and community identity.

11.1 The Economics of Architecture, Planning, and Landscaping

All built environments are shaped by economic forces:

- Land value and speculation: The cost of land influences density, affordability, and access. Rising values often drive gentrification and displacement.

- Construction costs: Labor, materials, logistics, and regulations determine project feasibility. Sustainable materials may have higher upfront costs but lower lifetime costs.

- Housing markets: Fluctuations in housing supply, interest rates, and investment incentives directly impact affordability and social equity.

- Infrastructure funding: Roads, transit systems, parks, water systems, and green infrastructure require sustained public and private investment.

Real estate development is often driven by profit motives that may conflict with long-term sustainability or public good—highlighting the need for balanced policy frameworks.

11.2 Housing Policy and Social Equity

Affordable, safe, and adequate housing is a universal human right—but in practice, it remains a global challenge. City and national governments use various tools to shape housing markets:

- Zoning and land use regulation: Control density, height, and use categories. Inclusive zoning can mandate affordable units in new developments.

- Rent control and subsidies: Aim to protect low-income tenants but require careful design to avoid disincentivizing construction.

- Public and cooperative housing: Provide alternatives to private ownership and speculative rental markets.

- Land trusts and community ownership models: Ensure long-term affordability by removing land from speculative markets.

Urban policy must also address homelessness, informal settlements, and climate migration, requiring coordination between governments, nonprofits, and communities.

11.3 Environmental Regulation and Green Incentives

Environmental performance is shaped not only by design but by law and incentives:

- Building codes: Mandate safety, energy efficiency, accessibility, and sometimes sustainability (e.g. insulation standards, green roofs, stormwater retention).

- Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA): Required for major projects to assess effects on ecosystems, water, air, and communities.

- Incentives for green building: Tax credits, grants, and expedited permitting for LEED-certified or net-zero buildings.

- Carbon pricing and emissions regulation: Influence material choices, transportation planning, and energy systems in urban development.

Policy can drive innovation—but it must be clear, enforceable, and equitable to be effective.

11.4 Governance and Urban Planning

City planning is an inherently political act—balancing public interest, private profit, and community voice. Governance models vary:

- Top-down planning: Centralized decisions, common in authoritarian or technocratic systems, can enable rapid transformation (e.g. Singapore, Dubai), but risk ignoring local needs.

- Bottom-up planning: Community-led or participatory planning fosters inclusivity and resilience but may lack resources or coherence without broader coordination.

- Public-private partnerships (PPPs): Blend government oversight with private capital, especially in infrastructure and real estate, but require transparency and accountability.

Effective governance requires interdisciplinary coordination, long-term vision, and civic education—ensuring that citizens understand and influence the shaping of their environments.

11.5 The Role of Culture and Leadership

Architecture and planning reflect cultural values, and can be profoundly shaped by the vision of leaders and institutions:

- Monarchs and statesmen throughout history—Ramses, Augustus, Napoleon, Haussmann—used architecture to express political power and cultural identity.

- Today, King Charles III has played a unique role in advocating traditional, human-scaled, and environmentally conscious architecture. His book A Vision of Britain critiques modernist excess and promotes design that respects historical context and community character.

- Indigenous leadership and traditional knowledge systems are increasingly recognized as vital to ecological and social sustainability.

Cultural narratives, rituals, and collective memory also influence how people relate to space and shape its future.

Conclusion:

Living spaces are not just physical environments—they are economic systems, legal domains, and moral choices. They reveal who has power, who has access, and what kind of future we are building. Just as design needs physics and art, it also needs justice and policy. Governance that supports equitable, sustainable, and participatory development is essential to the human dignity of all who dwell in cities, villages, and homes.

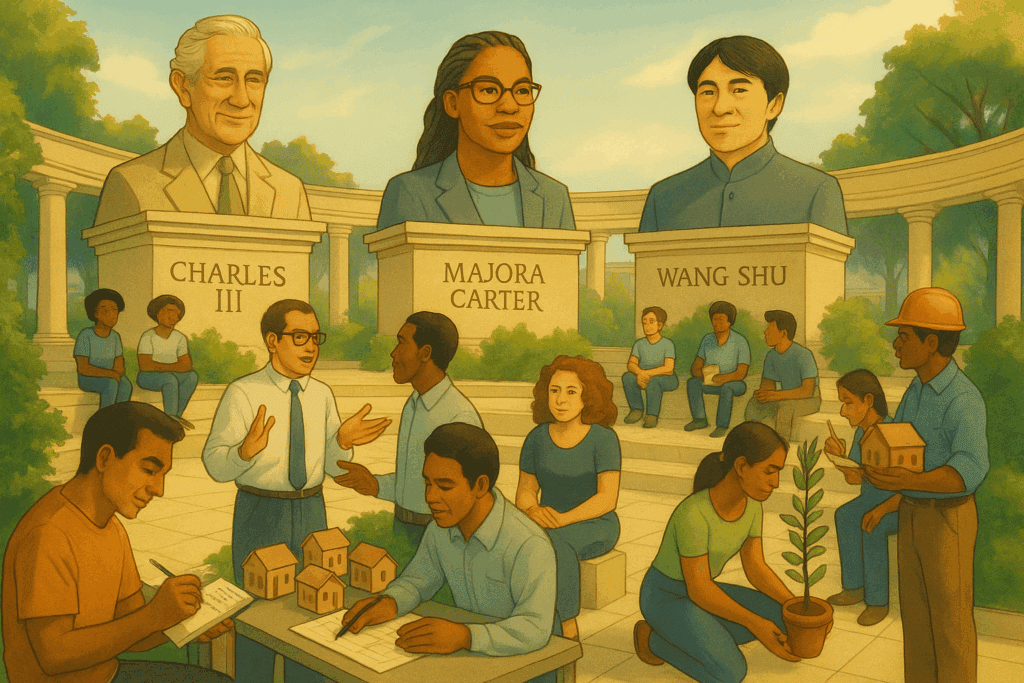

12. The Influence of King Charles III and Other Visionaries

Architecture is not only shaped by engineers, developers, and governments—it is also guided by public thinkers and visionaries who advocate for a more humane, sustainable, and meaningful built environment. Among the most prominent of these is King Charles III, who, long before ascending to the throne, made architecture and urbanism one of his personal crusades. His influence—both praised and contested—stands at the intersection of tradition, ecology, and cultural identity in the modern built world.

12.1 King Charles III: A Traditionalist with a Green Vision

As Prince of Wales, Charles championed what many considered an unfashionable cause: the revival of traditional architecture and urban forms. In 1989, he famously criticized a proposed modernist addition to the National Gallery in London as a “monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend.” This remark sparked a widespread debate about architectural values and cultural memory.

His key contributions include:

- A Vision of Britain (1989): In this book and accompanying documentary, Charles argued for architecture that respects human scale, local context, and classical proportion. He condemned the impersonality of glass-and-steel modernism and promoted craft, community, and heritage.

- The Prince’s Foundation for Building Community: Founded to promote sustainable urbanism and architectural education. It developed model communities like Poundbury in Dorset—a walkable, mixed-use, human-scaled town built according to traditional principles and ecological best practices.

- Environmental advocacy: Charles has been a strong proponent of green building, organic agriculture, and climate resilience—linking architectural beauty with planetary responsibility.

12.2 Architectural Legacy and Debate

Charles’s advocacy has had a tangible impact:

- His foundation’s design guides and community projects have influenced planning codes and sparked interest in vernacular architecture.

- His outspoken criticism of contemporary architecture has inspired both admiration and backlash. Critics argue he romanticizes the past and stifles innovation; supporters claim he restored dignity and purpose to public design.

- His emphasis on “architecture as service”—not self-expression—echoes deep traditions in both classical and sustainable thought.

While not an architect by training, Charles’s cultural authority and philosophical commitment have helped shape a broader discourse on the meaning and future of the built environment.

12.3 Other Global Visionaries in Architecture and Urbanism

Charles is part of a larger lineage of thinkers who have advanced transformative visions for how we build and inhabit space. These include:

- Jane Jacobs (USA): Urban activist and author of The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961). She championed vibrant, walkable neighborhoods, bottom-up planning, and the organic complexity of cities.

- Christopher Alexander (UK/USA): Architect and author of A Pattern Language (1977), which proposed timeless design solutions rooted in human psychology and lived experience.

- Hassan Fathy (Egypt): Advocated for sustainable, locally adapted architecture using traditional methods and materials—especially for the poor. His work integrated Islamic aesthetics with ecological and social concerns.

- Wang Shu (China): Pritzker Prize–winning architect who fuses modern forms with vernacular Chinese techniques and materials, emphasizing cultural memory and craftsmanship.

- Bjarke Ingels (Denmark): A new-generation designer known for integrating play, technology, and ecological thinking into bold urban forms.

- Majora Carter (USA): Urban revitalization strategist and champion of environmental justice, particularly in underserved neighborhoods affected by environmental racism.

- Ken Yeang (Malaysia): A pioneer in bioclimatic skyscrapers and vertical ecosystems—pushing green design into dense urban contexts.

These visionaries represent diverse philosophies, but all share a commitment to more humane, sustainable, and socially responsive environments.

Conclusion:

The built world reflects our values—and those values are shaped not only by laws and markets but by voices of conscience and imagination. Visionaries like King Charles III challenge us to think beyond fashion or efficiency. They ask: What is beauty? What is community? What is the good life? Their legacy is not just buildings—it is a renewed conversation about how we live with one another and the Earth.

13. Case Study – Jakarta and Nusantara: Capital Planning in the Age of Climate Change

As climate change accelerates and megacities strain under environmental and social pressures, governments around the world are being forced to rethink the physical locations of power and population. One of the most ambitious responses is Indonesia’s bold decision to relocate its capital from Jakarta—a rapidly sinking, overcrowded metropolis—to a purpose-built green city called Nusantara, deep in the forests of Borneo. This case offers a rare glimpse into 21st-century capital planning at the nexus of politics, ecology, and futuristic design.

13.1 Why Jakarta Can No Longer Sustain Its Role

Jakarta, with a population exceeding 30 million in its metropolitan region, faces a confluence of existential challenges:

- Land subsidence: The city is sinking at a rate of up to 25 cm per year due to excessive groundwater extraction, poor drainage, and tectonic vulnerability.

- Rising sea levels: Large portions of North Jakarta are already below sea level, threatening millions with displacement by mid-century.

- Overcrowding and congestion: Traffic paralysis and unregulated urban sprawl have made governance and emergency response extremely difficult.

- Environmental degradation: Air and water pollution, plastic waste, flooding, and collapsing infrastructure plague daily life.

Jakarta is not just overburdened—it is unsustainable as a seat of national governance.

13.2 The Vision for Nusantara

In 2019, President Joko Widodo announced the construction of Nusantara (“archipelago”) in East Kalimantan, a region of Borneo rich in biodiversity and natural resources. The city is designed to embody a futuristic, sustainable national vision.

Key Features of Nusantara:

- Decentralization: The city will be built from the ground up to host government institutions, reducing the political and economic hyper-concentration in Jakarta.

- Green infrastructure: The city plan emphasizes walkability, public transit, renewable energy, reforestation, and minimal emissions.

- Smart technology: AI-driven utilities, traffic management, and governance tools will be embedded from the outset.

- Cultural integration: The design aims to honor indigenous traditions and local knowledge, promoting harmony between modernity and heritage.

13.3 Challenges and Criticisms

Despite its ambition, Nusantara faces significant obstacles:

- Environmental impact: While intended to be green, the project will require clearing large tracts of forest—raising concerns about biodiversity loss, carbon emissions, and the displacement of wildlife and Indigenous communities.

- Social justice: Relocating the elite administrative class may deepen inequality unless accompanied by broad-based investment in education, housing, and opportunity.

- Cost and feasibility: The project is projected to cost over $30 billion. Economic uncertainty and political changes could delay or derail it.

- Climate paradox: While it aims to solve Jakarta’s problems, Nusantara itself may one day face climate risks—especially if deforestation continues across Borneo.

13.4 Global Comparisons: Other Planned Capitals

Nusantara joins a lineage of planned capitals designed to symbolize or achieve national transformation:

- Brasília (Brazil): Built in the 1960s to shift development inland, its futuristic architecture was both lauded and criticized for social detachment and inefficiency.

- Canberra (Australia): A compromise between rival cities Sydney and Melbourne, Canberra showcases thoughtful garden-city planning and national symbolism.

- Abuja (Nigeria): Replaced Lagos to reduce congestion and ethnic tensions, but has struggled with infrastructure and equity.

- Naypyidaw (Myanmar): Vast and underpopulated, it was built for military strategy more than civic functionality.

- Putrajaya (Malaysia): Successfully integrates Islamic architecture, digital governance, and green space, though also seen as a government enclave.

These examples illustrate the mixed legacy of capital relocation. Visionary plans often collide with real-world politics, budgets, and human needs.

13.5 Lessons and Futures

Nusantara represents a test case for future capital cities in an era of global ecological transformation:

- Can a nation design sustainability and democracy into its spatial core?

- Can a green city serve not just as a bureaucratic seat, but as a model of planetary ethics and ecological harmony?

- Will it remain a symbol, or become a system of real, daily benefit for its people?

Indonesia’s capital shift is more than a geographic move—it is a bet on the possibility that we can plan our way into a viable future.

Conclusion:

As cities around the world grapple with rising seas, failing infrastructure, and social fragmentation, the story of Nusantara offers a vision of what capital cities—and all cities—might become: nodes of regeneration, balance, and cultural continuity. But vision must meet responsibility. The real test will come not in the skyline, but in the soil, the air, the water—and the lives of those who call the city home.

14. Nested Systems – From Home and Garden to the Global Ecological Urban Network

A home is not an island. Nor is a city a self-contained machine. Every living space—whether a family dwelling, a neighborhood park, or a capital megacity—exists within a broader set of interlocking systems: ecological, economic, infrastructural, and cultural. Understanding architecture, landscaping, and city planning as nested systems is essential for designing resilient environments that function harmoniously at every scale—from the intimate to the planetary.

14.1 The Household as a Microcosm

The smallest scale of the built world is the home—a private space for rest, identity, and daily life. But a well-designed home is not an isolated shelter; it is a node of exchange and influence.

- Gardens and yards serve as ecological buffers, social spaces, and food sources.

- Water, energy, and waste systems in the home connect directly to municipal infrastructure.

- Mental and physical health are shaped by daylight, air quality, acoustics, and spatial comfort.

Designing sustainable homes involves passive solar principles, localized food production, efficient appliances, and adaptable space—all nested within community and climate.

14.2 Neighborhoods and Districts: The Middle Layer

Neighborhoods mediate between the household and the city.

- Walkability, mixed-use zoning, and green space determine quality of life and carbon footprint.

- Schools, clinics, markets, and places of worship provide shared services and social cohesion.

- Local ecosystems—streams, wetlands, tree cover—support biodiversity and climate regulation.

A healthy neighborhood balances density with openness, diversity with cohesion, and technology with tradition.

14.3 The City as an Urban Ecosystem

Cities are complex adaptive systems—social, infrastructural, and ecological.

- Transportation, utilities, and governance define the metabolic flows of energy, matter, and information.

- Parks, greenways, and green roofs create urban “lungs” and corridors for non-human life.

- Economic and cultural exchange make cities engines of innovation—but also centers of inequality and resource demand.

Resilient city planning integrates disaster preparedness, renewable energy, circular waste systems, and inclusive governance to align the built city with living systems.

14.4 The Bioregion and Nation: Landscape as Infrastructure

Cities exist within larger landscapes—forests, rivers, farmland, coastlines—that supply vital resources and services.

- Watersheds bind cities to mountains, wetlands, and coastal estuaries.

- Agricultural belts and food systems link urban tables to rural soil.

- Energy and material supply chains determine ecological footprint and geopolitical stability.

Planning at this level requires bioregional thinking—considering geology, climate, flora and fauna, and indigenous land stewardship in national and regional development.

14.5 The Global Mesh of Settlements and Systems

We now live in a global urban web: cities, towns, and infrastructures linked by supply chains, migration, data, and climate.

- The Anthropocene city is a planetary actor—both cause and victim of climate change.

- International cooperation on emissions, trade, conservation, and design standards is essential.

- Digital technologies and satellite monitoring allow cities to track their energy use, biodiversity, and waste flows in real time.

Projects like the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) aim to align local actions with global ecological and social priorities.

14.6 Design for Nested Resilience

Truly sustainable design operates simultaneously at multiple scales:

- A garden can clean water and feed pollinators.

- A school can harvest rain and teach ecological citizenship.

- A neighborhood can generate solar power and compost food waste.

- A city can sequester carbon and model justice.

- A nation can regulate emissions and protect biodiversity.

- A planet can heal—if its living spaces work together.

Conclusion:

To design well, we must think in systems—interconnected, nested, dynamic. A house is part of a street, which is part of a city, which is part of a watershed, which is part of a climate, which is part of a living planet. When each layer supports the others, we create not just structures, but habitats for flourishing—human and more-than-human alike.

15. Conclusion – Designing the Future of Life on Earth

Every home, garden, building, and city we create is an act of imagination—and responsibility. Architecture, landscaping, and city planning are more than utilitarian disciplines; they are the physical articulation of what we believe life should be. They reflect our values, our relationships with nature, and our aspirations for the future.

In the past, we built to protect ourselves from nature. Then we built to dominate it. Now, we are learning to build with nature—recognizing that the health of our living spaces and the health of our ecosystems are inseparable. As climate change, urban migration, and resource scarcity reshape the 21st century, the need for regenerative, equitable, and visionary design has never been more urgent.

The science of living spaces is no longer just about steel, concrete, or code. It is about systems thinking. It is about understanding the soil beneath our feet and the carbon in our air, the rituals of community and the data of traffic flow, the bird nesting in the roof garden and the child learning under skylit ceilings.

To design the future of life on Earth, we must:

- Integrate disciplines: Fuse architecture, ecology, engineering, public health, economics, and ethics into a single holistic process.

- Empower communities: Ensure all voices—especially the marginalized—are included in decisions about the places they inhabit.

- Think in time: Build not only for present needs but for future generations, with adaptability and resilience.

- Design for beauty and meaning: Recognize that spiritual, cultural, and psychological fulfillment is as vital as structural integrity or environmental metrics.

- Work at all scales: From the composting toilet to the carbon-neutral capital city, every design decision matters.

The city is not the enemy of nature—it is the test of our ability to live wisely within it. The garden is not just a retreat—it is a living classroom and carbon sink. The home is not just a shelter—it is the origin point of civilization.

As we move into an era of ecological limits and technological possibility, we must remember: the spaces we inhabit are also the spaces that shape us. If we wish to create a just, sustainable, and beautiful world, we must begin with the question: How shall we live—and where?

Final Note:

From ancient temples to green skyscrapers, from sacred groves to regenerative neighborhoods, the history and science of living spaces is the history and future of human life itself. Let us build with care. Let us design with wisdom. Let us inhabit the Earth as stewards, not just as settlers.