Table of Contents

Introduction:

- Why maps matter: understanding space, power, and perspective

- Overview of cartography’s journey from myth to machine

1. The Dawn of Mapping – Sacred Space and Symbolic Earth

- Mesopotamian clay tablets (e.g. Babylonian World Map, c. 600 BCE)

- Ancient Egyptian and Chinese maps

- Greek innovations: Anaximander, Ptolemy’s Geographia, and Eratosthenes’ measurement of the Earth

- Indigenous worldviews and cognitive cartography

2. Medieval and Religious Maps – Cosmology and Empire

- T and O maps, Mappa Mundi

- Islamic Golden Age geographers: Al-Idrisi’s world map (12th century)

- Chinese mapmaking: Song Dynasty cartography and naval charts

- Pilgrimage maps and early global contact

3. Renaissance and Age of Exploration – Mapping the Planet

- Mercator projection (1569) and its lasting influence

- Portolan charts and nautical innovations

- Colonialism, conquest, and cartographic propaganda

- First global atlases and printing revolution

4. Scientific Cartography and National Mapping Projects

- Triangulation, topographic surveys, and land measurement

- Ordnance Survey (UK), Cassini maps (France), USGS

- Geological, meteorological, and astronomical mapping

- Mapping for war and empire: Napoleonic and World War maps

5. The Digital Turn – Satellites, GPS, and Remote Sensing

- The launch of Sputnik (1957) and the space-based mapping revolution

- Landsat, NASA missions, and satellite imaging

- GPS development and military origins

- GIS (Geographic Information Systems) and spatial databases

6. Everyday Mapping – From GPS to Google Earth

- The rise of consumer GPS (Garmin, TomTom)

- Google Maps, Street View, and real-time navigation

- Crowdsourced mapping (OpenStreetMap, crisis response maps)

- Social mapping: data layers, reviews, and behavior tracking

7. The Intelligence of Space – Geospatial Analytics and Surveillance

- Government use: NGA, NSA, and geospatial warfare

- Corporate geointelligence and smart cities

- AI and predictive mapping

- Ethical implications: privacy, power, and misinformation

8. The Future of Mapping – Augmented Earth to Cosmic Charts

- Augmented reality and wearable maps

- Mapping oceans, DNA, and digital metaverses

- Deep space cartography: James Webb and beyond

- A unified map of the Known Universe

Conclusion: Mapping Meaning – Humanity’s Evolving Mirror

- Maps as tools, metaphors, and visions

- The moral geography of future worldmaking

Introduction: Mapping Our Place in the Cosmos

Since the dawn of civilization, humans have sought to understand the world around them by drawing it. From sacred etchings on clay tablets to digital atlases accessible with a tap of the finger, maps have served not only as navigational tools, but as mirrors of human understanding, imagination, and power.

They chart the known and speculate on the unknown. They guide armies and pilgrims, explorers and algorithms. In every era, maps have revealed as much about the people who made them as the lands they aimed to represent.

At their core, maps are answers to timeless questions: Where am I? What’s around me? How do I get there? Yet the tools we’ve used to answer these questions have evolved radically—driven by revolutions in science, technology, and geopolitics.

Early maps described cosmological visions rather than geographic precision. Later, maps became instruments of empire and trade. In the modern era, they became scientific and statistical, and today they are increasingly intelligent, interactive, and omnipresent.

This article traces the remarkable arc of cartographic history—from mythic river-worlds and hand-drawn portolan charts to AI-generated maps of global behavior and interstellar cartography. Along the way, it explores how advances in measurement, mathematics, printing, optics, satellite imaging, GPS, and data science have transformed mapmaking from a craft of speculation into a science of geospatial intelligence.

We now live in a world where maps don’t just show us where we are—they anticipate where we might go. They optimize travel, predict floods, track epidemics, and even influence how cities are built. And as humanity turns its gaze beyond Earth, we are beginning to map planets, moons, and the farthest reaches of the observable universe.

To understand maps, then, is to understand how humans make meaning of space, power, and possibility. It is to chart not just the Earth, but the evolution of our minds and civilizations.

Let us begin at the beginning: when the world was small, sacred, and only partially drawn.

1. The Dawn of Mapping – Sacred Space and Symbolic Earth

Long before the age of precision instruments and satellite imagery, early humans began shaping their understanding of the world with the most available tools: memory, myth, and symbol. The first maps were not empirical records of geographic fact but deeply symbolic representations of space and meaning. They depicted not just landscapes, but cosmologies—blending physical topography with spiritual, social, and political significance.

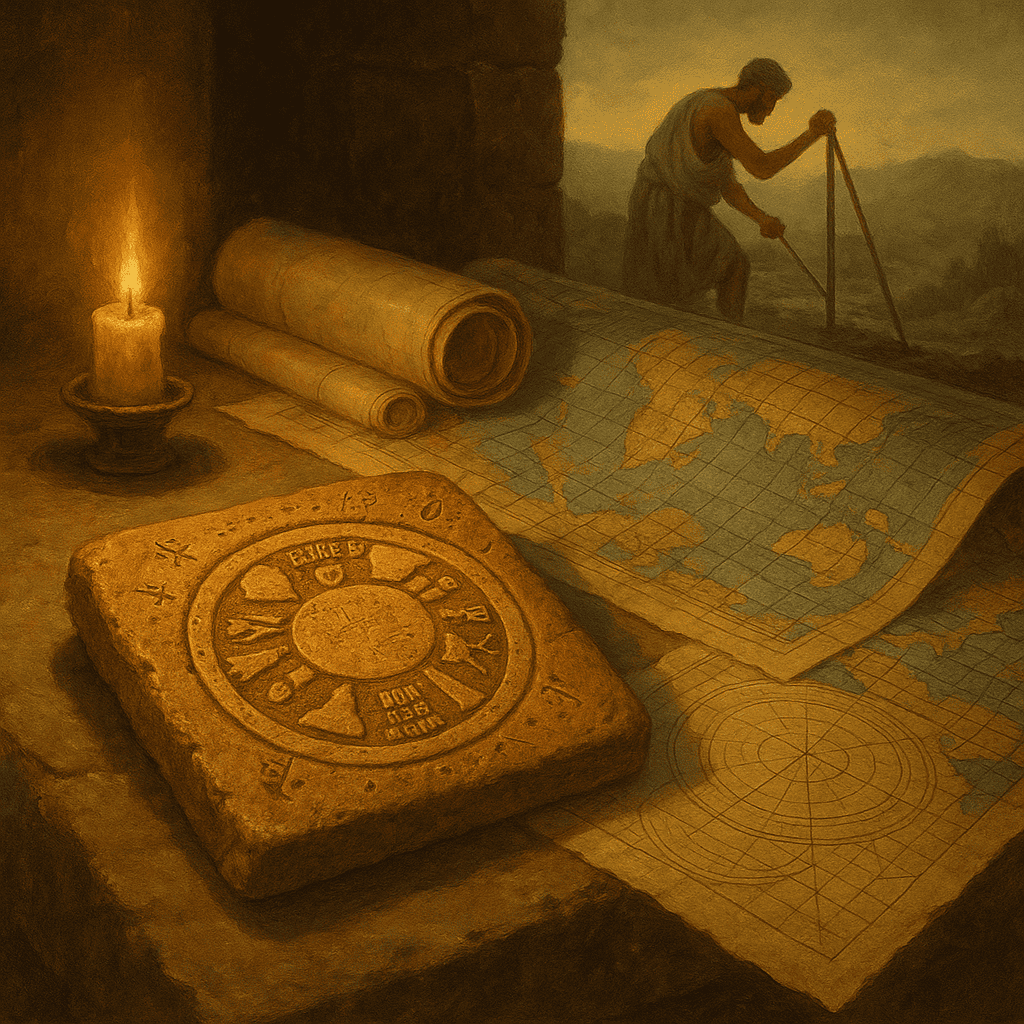

1.1. Mesopotamian Maps – The Earliest Cartographic Artifacts

The oldest known map in the world is the Imago Mundi, a clay tablet from Babylon dated to around 600 BCE. Discovered near the ancient city of Sippar in modern Iraq, the map depicts a circular world with Babylon at the center, surrounded by a ring of water labeled the “Bitter River” (likely the ocean). Beyond this ring lie mysterious “regions” or islands described with mythic overtones.

This early attempt at world-mapping reveals how ancient cultures fused geography with theology and imperial ideology. Babylon, as the political and spiritual center of the world, was placed at the heart of the cosmos—a motif echoed in many early cultures.

1.2. Egyptian and Chinese Mapping Traditions

In ancient Egypt, mapmaking was used for practical and religious purposes. Papyrus maps, such as the Turin Papyrus Map (c. 1160 BCE), show detailed representations of mining regions and topographical features, including hills, valleys, and roads. These maps supported both resource extraction and funerary planning, blending utility with cosmological alignment.

Meanwhile, early Chinese cartography, dating back to the Warring States period (5th–3rd centuries BCE), emphasized political geography and administrative control. Wooden block maps and silk scrolls showed regions in stylized detail. The Chinese tradition also introduced systematic grid-based representations and early use of scale—a significant step toward scientific cartography. The philosopher Mozi and later scholars like Zhang Heng explored celestial and terrestrial mapping in increasingly mathematical ways.

1.3. Greek Innovations – Measuring and Mapping the Earth

The Greek world marked a turning point in cartographic history by introducing measurement and abstract reasoning. Anaximander (6th century BCE), often credited as the first Greek cartographer, created a world map centered on the Aegean, surrounded by oceans and encircled by a ring of fire. Though mostly speculative, it signaled a shift from mythic geography to rational abstraction.

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (276–194 BCE), head librarian at the Library of Alexandria, took the next great leap: using geometry and solar angles, he calculated the circumference of the Earth with astonishing accuracy. He also invented the concept of latitude and longitude. Ptolemy (2nd century CE), in his Geographia, compiled a gazetteer of over 8,000 place names with coordinates—a monumental synthesis of Roman and Greek knowledge that shaped Islamic and European cartography for over a millennium.

1.4. Indigenous Maps and Cognitive Cartography

While ancient empires left behind durable maps on stone and parchment, Indigenous peoples around the world developed sophisticated, often ephemeral mapping systems rooted in oral tradition, symbolic knowledge, and kinesthetic memory. Polynesian navigators used stick charts made of wood and shell to model ocean swells and island positions. Aboriginal Australian songlines functioned as memory-maps encoded in mythic storytelling, guiding individuals across vast landscapes through ancestral narratives.

These systems reveal an alternate form of cartographic intelligence—one not reliant on visual scale or fixed coordinates, but deeply embedded in ecological perception, ritual, and the rhythms of life.

Early Map Functions

| Culture | Key Feature | Function |

| Babylonian | Centralized sacred geography | Imperial and cosmological |

| Egyptian | Topographical mining maps | Economic and ritual |

| Chinese | Scaled administrative scrolls | Bureaucratic control |

| Greek | Latitude/longitude systems | Scientific theorization |

| Indigenous | Embodied oral-visual maps | Environmental navigation |

Thus, the first maps were not merely attempts to locate terrain—they were acts of worldview creation. They placed human beings in relation to gods, kings, rivers, and stars. They defined centers and edges, ordered chaos into cosmos, and laid the groundwork for the spatial imagination that would shape the future of civilization.

2. Medieval and Religious Maps – Cosmology and Empire

As ancient empires fell and new religious civilizations rose, the art and science of mapping transformed once again. In the medieval period, maps became less about measurement and more about meaning. They illustrated divine order, spiritual geography, and sacred history. The world was not charted as an objective surface to be navigated, but as a symbolic stage upon which divine and human dramas unfolded. In both Christian and Islamic worlds, cartography served theological, political, and educational purposes—reinforcing cosmologies of power, faith, and civilization.

2.1. Christian Mappa Mundi – Sacred History in Space

One of the most iconic medieval map types in Europe is the Mappa Mundi (“map of the world”). These were not navigational instruments but religious artworks—visual sermons that conveyed Christian cosmology and history. The most famous is the Hereford Mappa Mundi (c. 1300), which places Jerusalem at the center of a circular world, with east (Eden and Paradise) at the top.

The three known continents—Asia, Europe, and Africa—are shown in stylized form, populated with biblical events, monstrous races, and legendary creatures. These maps taught moral lessons and situated Christendom at the metaphysical heart of creation. Orientation and scale were subordinate to spiritual symbolism.

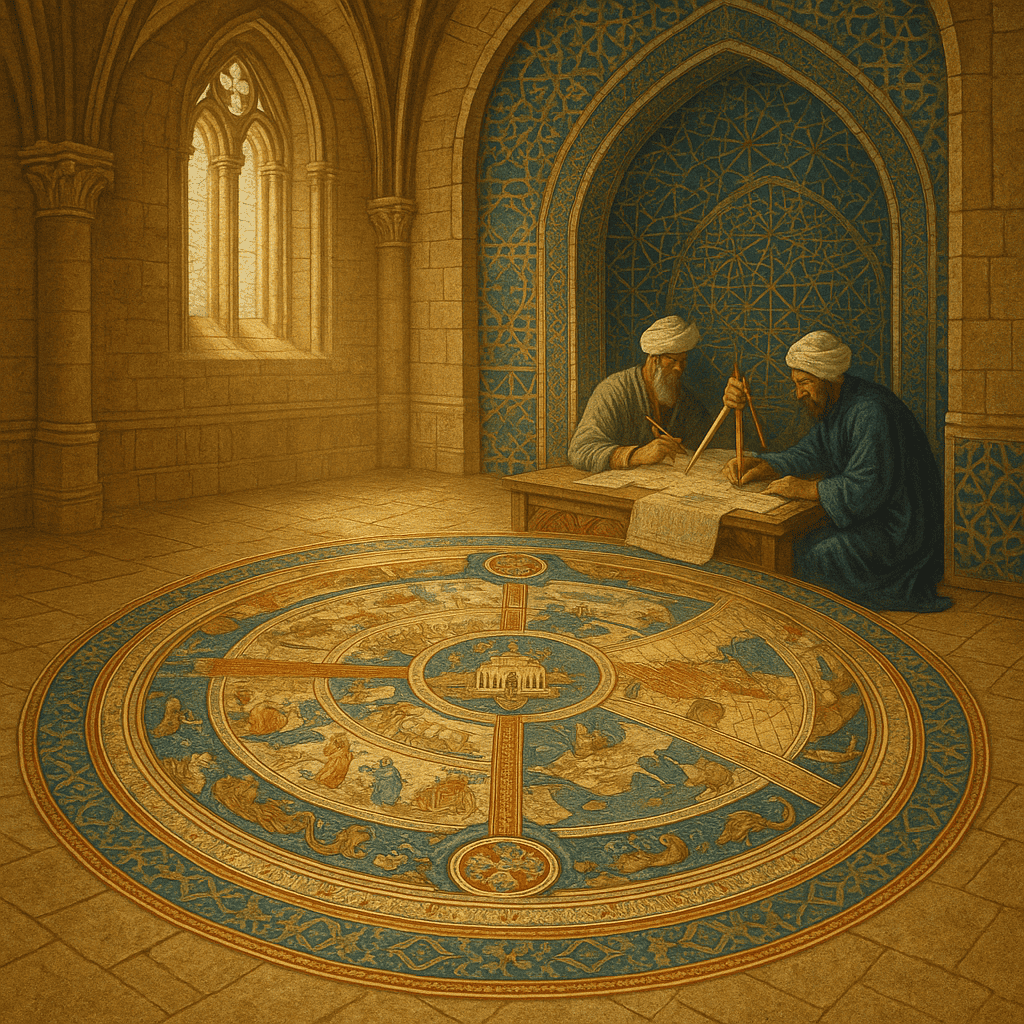

2.2. Islamic Cartography – Geometry and the Global Ummah

In the Islamic Golden Age (8th–14th centuries), Muslim scholars synthesized Greek, Persian, and Indian geographical knowledge into sophisticated cartographic works. Unlike their Christian counterparts, Islamic geographers were often concerned with empirical observation and navigational accuracy, especially to support pilgrimage (hajj), trade, and statecraft.

Al-Khwārizmī (9th century) produced one of the first comprehensive atlases of the known world, revising Ptolemaic coordinates and correcting misconceptions. Later, al-Idrīsī (1100–1165), working in Sicily, compiled the Tabula Rogeriana for King Roger II—a remarkably accurate and detailed map of Eurasia and North Africa, south-oriented, accompanied by systematic geographic texts.

Islamic maps were typically oriented with south at the top and often structured according to mathematical grids. They reflect a blend of scientific ambition and theological framing, including depictions of Mecca as a fixed spiritual pole.

2.3. Chinese Cartography – Empire and Order

During the Tang and Song Dynasties (7th–13th centuries), China produced some of the most advanced maps in the world. Emperors commissioned large-scale maps for military planning, river control, taxation, and governance. Chinese cartographers employed grid systems, compasses, and measured distances—well before their widespread use in the West.

The Yu Ji Tu (Map of the Tracks of Yu), engraved in 1137 on stone, depicts China’s rivers, mountains, and administrative divisions in meticulous relief using a rectangular coordinate grid. It shows an early commitment to spatial rationalism that reflected Confucian ideals of harmony and statecraft.

2.4. Pilgrimage, Trade, and Cross-Cultural Maps

Medieval cartography was also shaped by human movement: pilgrims walking sacred paths, merchants crossing the Silk Road, and sailors tracing monsoon winds. Pilgrimage maps such as the Ebstorf Mappa Mundi and Christian itinerary guides offered spiritual direction rather than geographic precision.

In East Asia, Japanese Gyōki-type maps combined Buddhist cosmology with imperial geography. In India, temple cartography linked sacred topography to mythic cosmology. Cross-cultural maps appeared in cosmopolitan centers like Cairo, Baghdad, and Constantinople—where Jewish, Christian, and Muslim cartographers exchanged ideas.

2.5. Power and Persuasion in the Medieval Map

Across regions, medieval maps were tools of persuasion. They asserted divine order, legitimized political authority, and framed the unknown as morally charged or spiritually dangerous. Cartographic space was not empty and neutral—it was filled with purpose, boundaries, and significance.

Mapping the Medieval Mind

| Culture | Map Type | Center of the World | Key Purpose |

| Christian Europe | Mappa Mundi | Jerusalem | Teach sacred history |

| Islamic World | Mathematical Atlases | Mecca | Navigate and unify the Ummah |

| China | Grid Maps (Fangzhen) | Imperial Capital | Govern vast territory |

| Japan & India | Pilgrimage Cosmograms | Sacred mountains or shrines | Embody spiritual journey |

In the medieval imagination, maps were not merely instruments of location, but windows into divine design. They reflected a world in which space, time, and truth were interpreted through sacred texts and imperial ideologies. But as the Age of Exploration dawned, the need to cross oceans and measure coastlines would give rise to a new cartographic paradigm—one driven by instruments, conquest, and global ambition.

3. Renaissance and Age of Exploration – Mapping the Planet

The Renaissance era ignited a profound transformation in human understanding of the world—intellectually, artistically, and geographically. It was a time when the medieval worldview collided with new discoveries, instruments, and ambitions. Fueled by maritime exploration, scientific inquiry, and printing technology, cartography evolved into a practical science and a strategic tool for empire-building.

Maps began to resemble the Earth more closely than the heavens. They were no longer drawn primarily to honor the divine but to guide ships, divide continents, and project imperial power. Cartographers became geographers, technicians, and sometimes propagandists, shaping the way the world would be seen, owned, and controlled.

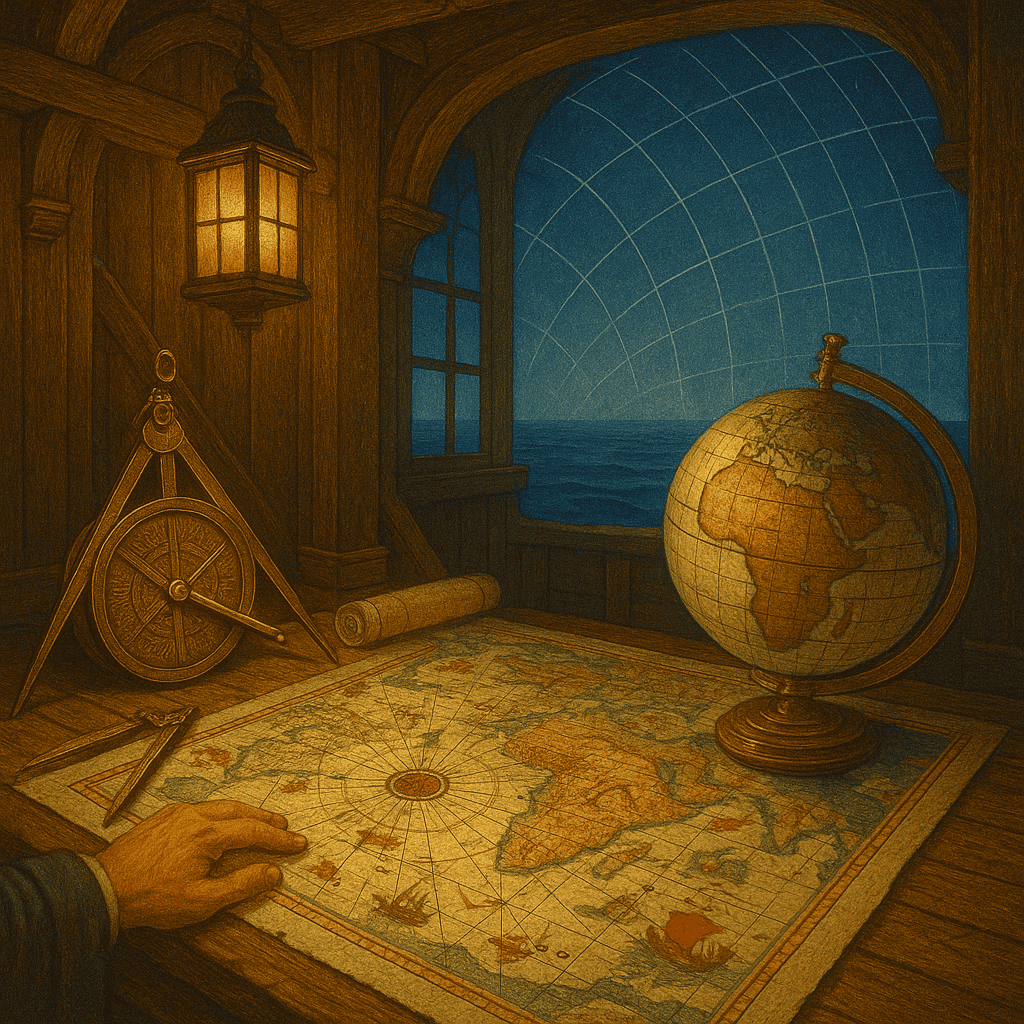

3.1. Portolan Charts – Precision at Sea

One of the most significant innovations of this period was the portolan chart, first appearing in the 13th century and flourishing during the 14th–16th centuries. These maps, drawn on vellum, showed coastlines with striking accuracy, incorporating compass roses and rhumb lines radiating in all directions. Used by Mediterranean sailors, they prioritized practical knowledge of ports, currents, and wind patterns over landmass detail.

Unlike symbolic medieval maps, portolans were based on real observations and measurements. They marked the beginning of empirically grounded cartography—maps meant to be used, not just contemplated.

3.2. Mercator and the Projection Problem

Perhaps no name is more synonymous with Renaissance cartography than Gerardus Mercator (1512–1594). In 1569, he introduced the Mercator projection, a cylindrical map projection that preserved angular direction, making it invaluable for navigation. Although it distorted size—especially near the poles—it allowed for straight-line compass bearings on a flat surface.

Mercator’s projection shaped Western conceptions of geography for centuries. It privileged European and northern regions in scale, reinforcing imperial viewpoints. The map was a mathematical marvel—and a political statement.

3.3. The Atlas is Born – Ortelius and Global Compilation

Abraham Ortelius’s Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (1570) is considered the first modern atlas—a systematically compiled, published collection of uniform world maps. It reflected a new drive toward geographic knowledge as a public good, not just the secret of merchants or monarchs.

Atlases like Ortelius’s became intellectual commodities, tools of diplomacy, education, and commerce. They spread geographic literacy and fueled curiosity about foreign lands and peoples—though often filtered through European eyes.

3.4. Maps as Tools of Conquest

During the Age of Exploration, maps became instruments of colonial expansion. As European empires reached Africa, the Americas, Asia, and the Pacific, they produced increasingly detailed and extractive maps of conquered lands—often before full territorial control was established.

Cartographers accompanied explorers, missionaries, and merchants, translating unfamiliar terrain into surveyed lines, resource zones, and imperial claims. The map was not just a record of what had been found—it was a declaration of intent. To name a place on a map was to stake a claim to it.

Meanwhile, Indigenous mapping traditions were often ignored, overwritten, or incorporated without credit. The cartographic gaze became an extension of imperial vision: to see was to dominate.

3.5. Printing, Reproduction, and Cartographic Standardization

The invention of the printing press revolutionized the dissemination of maps. Woodcuts and copperplate engravings allowed maps to be duplicated with fidelity and distributed widely. Standardization improved. Errors could be corrected across editions. For the first time, the general public—at least in literate societies—could access visual representations of the world beyond their immediate experience.

By the 17th century, mapmaking had become a respected professional discipline in many European capitals. National academies, naval offices, and colonial companies employed teams of geographers to chart trade routes, resources, and borders. Cartography was now fully enmeshed in statecraft and science.

Renaissance Map Milestones

| Date | Innovation | Significance |

| 1325 | Portolan Charts | Coastal accuracy for navigation |

| 1569 | Mercator Projection | Angular fidelity for ocean travel |

| 1570 | Ortelius Atlas | First standardized global atlas |

| 1595 | Posthumous maps by Mercator | Division of the world into detailed regional sheets |

| 1600s | Dutch Golden Age cartography | Peak of aesthetic and scientific European mapmaking |

The Renaissance remade the world—and its maps. No longer merely theological diagrams or symbolic scripts, maps became instruments of expansion, exploitation, and scientific curiosity. They gave shape to empires, fueled the voyages of Columbus and Magellan, and brought the known and unknown into a single, flattened view.

But even as maps grew more accurate, their power to influence perceptions—of self, other, and world—only deepened. The next stage of cartography would see the Earth measured in ever finer detail by theodolites and telescopes, stitched together by triangulation, and classified by landform and layer: the birth of scientific cartography.

4. Scientific Cartography and National Mapping Projects

By the 18th and 19th centuries, cartography was no longer the domain of navigators and mystics alone. It became a fully scientific enterprise, grounded in mathematics, instrumentation, and systematic data collection. Across Europe, the Americas, and parts of Asia, governments began to sponsor massive national mapping efforts—motivated by military strategy, taxation, infrastructure, and territorial administration.

This period saw the transformation of maps from handcrafted artworks or exploration journals into precise, replicable documents of measurement and surveillance. Cartographers became surveyors, engineers, and civil servants. The world was not just described—it was dissected, standardized, and indexed.

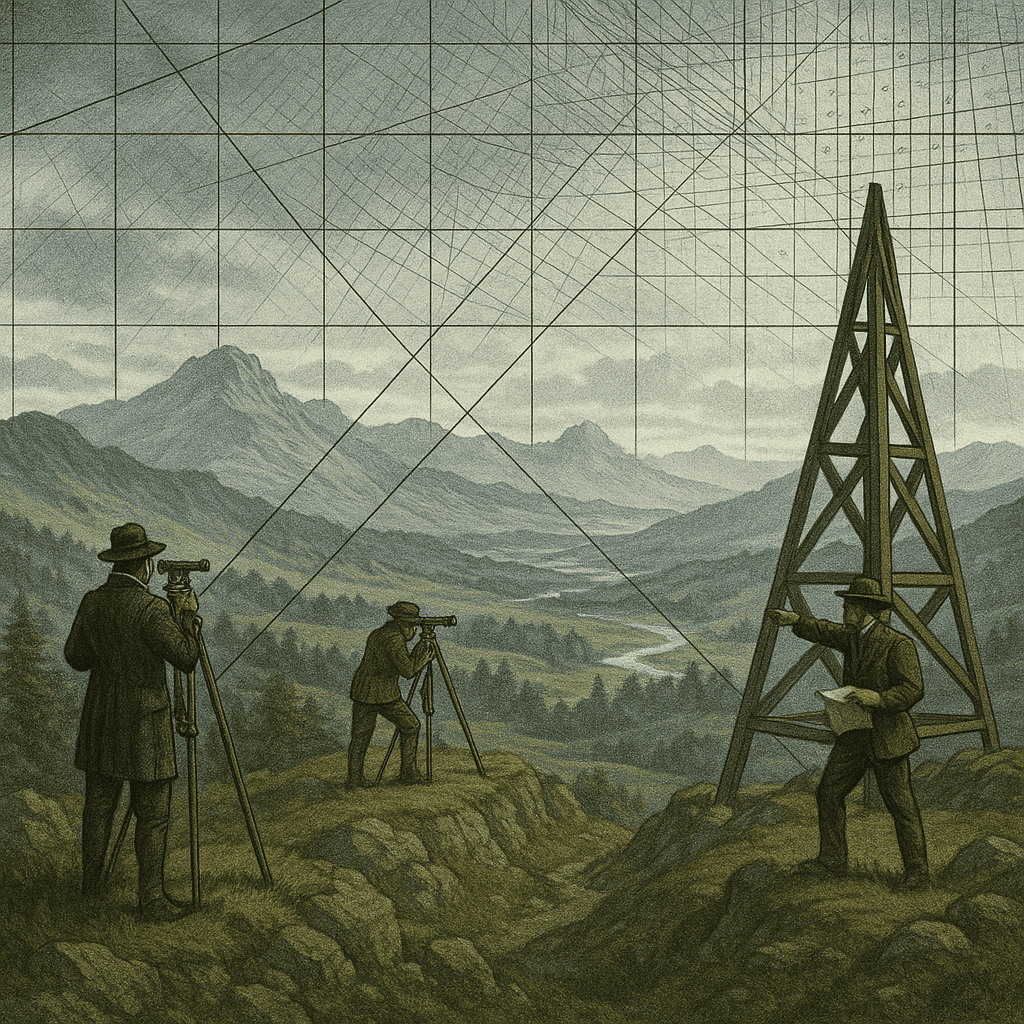

4.1. Triangulation and the Measurement of the Earth

One of the defining technologies of scientific cartography was triangulation—the use of geometry to determine distances and locations based on angles between fixed points. This method allowed for unprecedented accuracy in large-scale surveys.

Jean Picard’s 17th-century work in France laid the groundwork for measuring degrees of latitude, and in the 18th century, the French Geodesic Mission attempted to measure the shape of the Earth (flattened at the poles) by triangulating arcs near the equator and in Lapland.

The result was a new understanding of the Earth as a geometric object: a spheroid that could be mathematically modeled and charted with precision.

4.2. The Rise of National Survey Agencies

Governments across Europe began to formalize mapping institutions:

- France: The Cassini family produced the first systematic topographic map of France (Carte de Cassini, 18th century) using a nationwide triangulation network.

- United Kingdom: The Ordnance Survey (founded 1791) mapped Britain with military precision following fears of French invasion. Its detailed maps became a model for national cartographic excellence.

- United States: The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS, founded 1879) combined topographic, geological, and resource mapping—tying cartography to westward expansion and land use planning.

These projects required not only technical skill but bureaucratic will. They institutionalized mapping as a function of the modern state—connecting geography to sovereignty, development, and science.

4.3. Geological, Meteorological, and Astronomical Mapping

In the 19th century, cartography expanded into other scientific disciplines. Geologists used maps to chart mineral deposits, fault lines, and mountain formations—tools essential for mining, railroads, and engineering. Meteorologists mapped weather systems, storm paths, and climate zones. Astronomers produced celestial maps of the heavens with increasing precision.

The boundaries between disciplines began to blur. Maps became multi-layered representations of physical, chemical, and atmospheric phenomena. With the invention of contour lines, elevation and depth could now be visualized—bringing topography to life.

4.4. Maps of War and Empire

Scientific maps were also tools of conflict. Napoleon’s campaigns were supported by the Bureau Topographique, which produced detailed military maps. In the American Civil War, cartographic intelligence influenced troop movements. Colonial powers mapped their new holdings to facilitate extraction, pacification, and administrative control.

Cartography became an essential branch of the modern military. Knowing the terrain meant knowing how to dominate it.

4.5. Standardization and the Global Grid

International conventions began to emerge to standardize map formats, symbols, and coordinates. The 1884 International Meridian Conference established the Greenwich Meridian as the global prime meridian, paving the way for global time zones and international navigation standards.

With longitude and latitude fully systematized, the Earth was now a grid—a continuous surface that could be charted, coded, and divided. It set the stage for future developments in aerial mapping, photography, and, eventually, satellite geolocation.

The Age of Scientific Mapping

| Project | Nation | Focus | Legacy |

| Carte de Cassini | France | Triangulated topographic mapping | First national-scale survey |

| Ordnance Survey | UK | Military and civil mapping | Gold standard for detailed accuracy |

| US Geological Survey | USA | Topography and natural resources | Linked mapping to public land use |

| International Meridian Conference | Global | Coordinate standardization | Established Greenwich as 0° longitude |

In this era, the map became a machine-readable reality—a coded surface on which science, governance, and ambition converged. It reflected not just territory, but order; not just land, but law. But even this rational cartographic regime would be transformed again—when the view from above, from aircraft and satellites, would render the entire planet visible in near-real time.

5. The Digital Turn – Satellites, GPS, and Remote Sensing

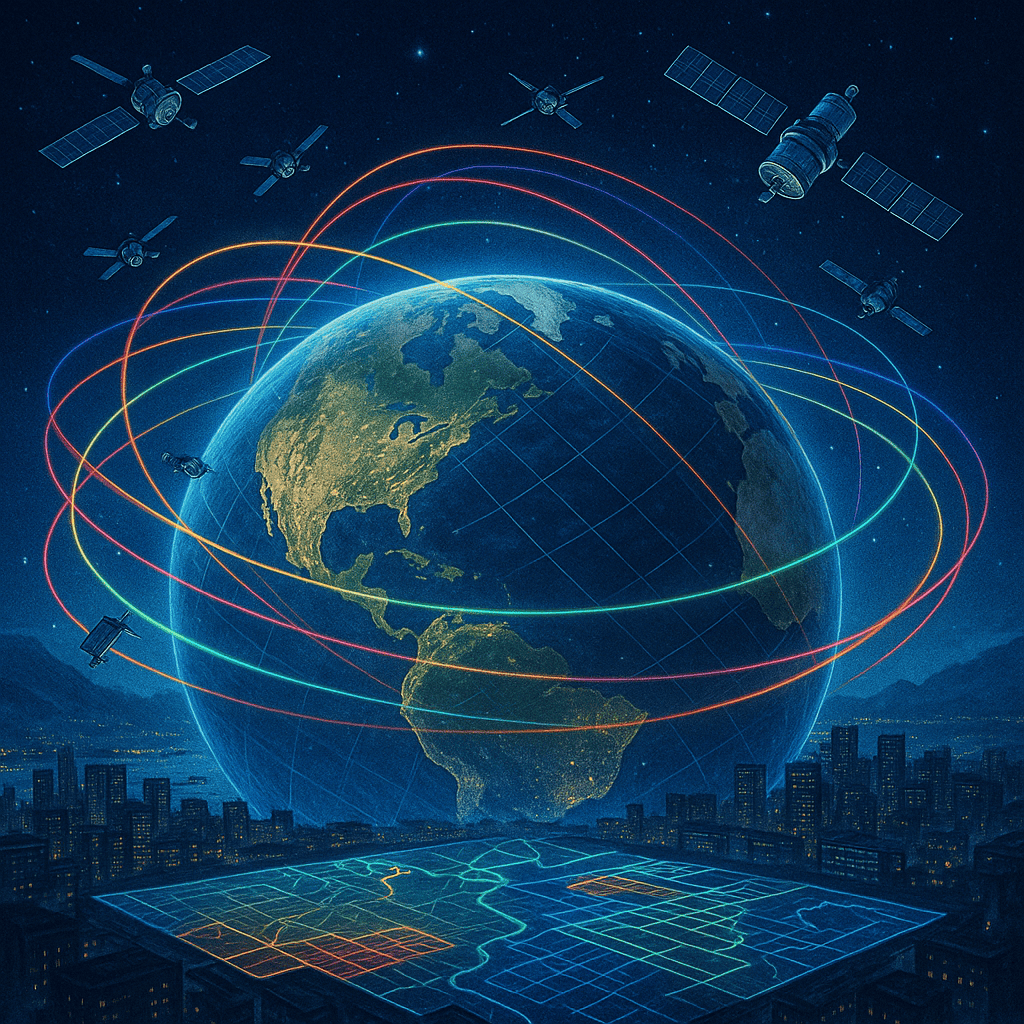

The mid-20th century ushered in the most radical transformation in cartographic history since the invention of printing. With the advent of rocketry, orbital satellites, and computer technology, the map was no longer confined to hand-drawn representations or terrestrial measurement. For the first time, humanity could see the Earth from above—and map it from space.

This shift gave rise to digital cartography and remote sensing, transforming maps into dynamic, data-driven systems. It made possible real-time navigation, environmental monitoring, and an entirely new field: geospatial intelligence.

5.1. The Space Age and Earth Observation

The launch of Sputnik 1 by the Soviet Union in 1957 marked the dawn of space-based observation. In the 1960s and 1970s, NASA launched Earth-observing satellites such as Landsat, which continuously photographed and scanned the planet’s surface. These satellites offered data on forests, agriculture, urban growth, and water cycles—opening the way for planetary-scale environmental science.

Multispectral and infrared imaging allowed researchers to “see” beyond the visible spectrum—detecting heat signatures, pollution, and geological formations with extraordinary precision.

5.2. Global Positioning System (GPS)

Developed by the United States Department of Defense and operational by the 1990s, the Global Positioning System revolutionized navigation. By using a constellation of satellites and ground stations, GPS enabled users to pinpoint their location anywhere on Earth with remarkable accuracy.

What began as a military tool quickly became a public utility. From airplanes and cargo ships to smartphones and wristwatches, GPS embedded geolocation into daily life. It allowed for live tracking, route optimization, and even time synchronization across global systems.

5.3. Geographic Information Systems (GIS)

Another pivotal technology was the Geographic Information System—a software framework that allows data to be stored, analyzed, and visualized in spatial layers. Developed in the 1960s and commercialized in the 1980s and 90s, GIS turned maps into analytical tools.

Using GIS, researchers and policymakers could overlay layers such as population density, rainfall, election results, and traffic patterns—revealing correlations and guiding decisions. GIS is used in fields as diverse as epidemiology, urban planning, agriculture, logistics, conservation, and disaster response.

5.4. From Pixels to Patterns – Big Data Mapping

With the rise of satellites and sensors, the world became saturated with geospatial data. Algorithms and artificial intelligence began to analyze patterns invisible to the human eye—identifying deforestation, predicting disease outbreaks, monitoring climate change, and detecting illegal mining or conflict zones.

Maps ceased to be static snapshots and became dynamic, predictive tools—refreshed in near-real time. The line between map and model blurred.

5.5. Open Data and Global Participation

The digital revolution also democratized mapping. Open-source platforms like OpenStreetMap allowed anyone to contribute data, especially in regions poorly mapped by governments or corporations. In natural disasters and humanitarian crises, crowdsourced maps have become lifelines—updated by volunteers using satellite images and reports from the ground.

Mapping shifted from top-down control to bottom-up collaboration, giving rise to a new kind of citizen geographer.

Key Technologies of the Digital Cartographic Age

| Technology | Launch | Function | Impact |

| Landsat Program | 1972–present | Earth imaging via satellite | Longest continuous record of Earth’s surface |

| GPS | 1978–95 | Satellite-based navigation | Universal geolocation for military and civilian use |

| GIS | 1960s–present | Layered spatial data analysis | Enabled data-driven mapping in all major fields |

| Remote Sensing | Ongoing | Imaging with radar, LiDAR, infrared | Multispectral Earth observation |

| OpenStreetMap | 2004 | Crowdsourced cartography | Empowered local mapping and crisis response |

In the digital age, maps are no longer just representations—they are systems. They breathe, update, calculate, and learn. They respond to movement, integrate with sensors, and interact with users in real time. The Earth itself has become a mapped interface—readable, searchable, and analyzable on a planetary scale.

And yet, the digital turn is not the end. It is a threshold. In the next phase, maps would not only guide individuals and governments, but shape how global societies behave, predict how ecosystems evolve, and explore what lies far beyond Earth.

6. Everyday Mapping – From GPS to Google Earth

By the early 21st century, digital cartography had leapt from the realms of scientific and military application into the pockets and homes of billions. What was once the purview of governments, corporations, and universities is now embedded in our phones, cars, watches—even augmented glasses. Mapping is no longer occasional—it is continuous, ambient, and personalized.

The convergence of GPS, internet connectivity, and mobile computing produced a cultural revolution: the era of everyday mapping. Today, maps do not merely reflect geography—they shape behavior, commerce, memory, and even identity.

6.1. The Rise of Consumer GPS

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, consumer-grade GPS devices exploded in popularity. Brands like Garmin, TomTom, and Magellan offered standalone devices for cars, hikers, and boaters. For the first time, individuals could access real-time directions, location tracking, and speed data without the need for paper maps.

This development shifted the average person’s spatial awareness—people began to rely on satellites instead of memory or printed guides. Navigation became automated, turning drivers into passive participants in digital systems of orientation.

6.2. Google Maps and the Digital Earth

Launched in 2005, Google Maps was the watershed moment for public digital mapping. Combining street-level data, satellite imagery, turn-by-turn navigation, and later crowdsourced updates, it became the most used mapping platform in history.

In tandem, Google Earth gave users a dynamic 3D globe—allowing them to “fly” anywhere on the planet, explore terrain, and view time-lapse changes in landscapes. This transformed geography education and public understanding of global environments.

These tools integrated with search engines, calendars, contacts, and advertising—creating a unified platform where spatial behavior was not only supported, but analyzed and monetized.

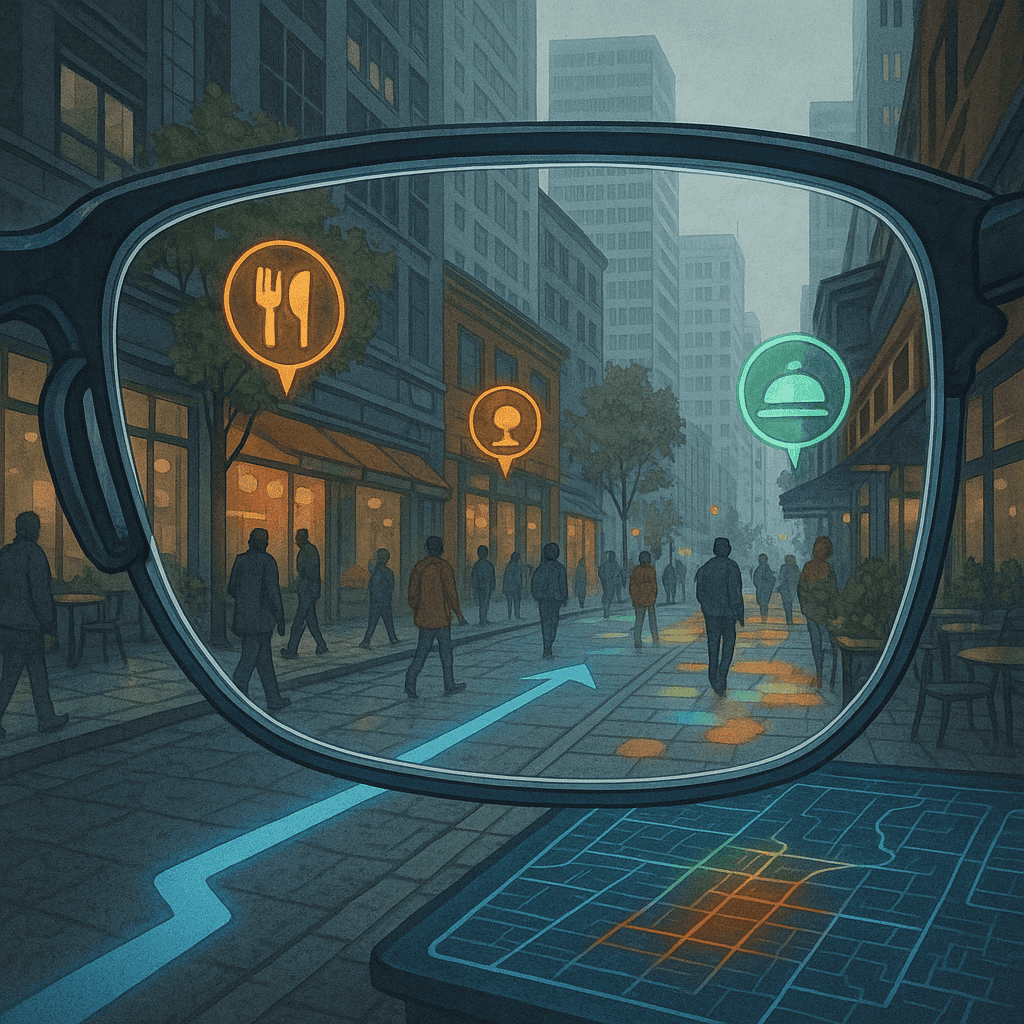

6.3. Street View, AR, and Visual Navigation

With Street View (2007), mapping took a dramatic leap toward immersion. Mounted cameras captured panoramic imagery of cities, streets, and landmarks across the globe. Users could virtually walk neighborhoods, explore real estate, or revisit places from the past.

Soon after, augmented reality (AR) navigation was introduced. Apps like Google Live View and Apple Maps AR overlay directional arrows and place markers onto live camera feeds, guiding users in real time through urban environments.

The boundary between the map and the world began to dissolve.

6.4. Crowdsourcing and Live Data Layers

Platforms like Waze and OpenStreetMap harnessed collective intelligence, allowing users to report traffic, hazards, construction, and errors. Real-time traffic data now informs routing decisions, with algorithms optimizing commutes minute-by-minute.

Layered data visualizations—such as bike lanes, restaurant reviews, air quality, and transit schedules—have turned maps into decision platforms, not just orientation tools.

Mapping has become context-sensitive and predictive: Where should I go? When should I leave? What’s the best option?

6.5. The Social and Ethical Dimensions of Mapping

Everyday mapping brings unprecedented convenience—but also raises concerns. Tech companies now collect vast geolocation data tied to user identities. This information is used to target ads, monitor behavior, influence consumption, and optimize services.

Digital maps are also mirrors of power: neighborhoods with higher digital activity receive more detailed updates, while underserved areas remain blank or outdated. Maps shape perception—and what is omitted can be as significant as what is shown.

Moreover, dependence on GPS and visual navigation can degrade innate spatial memory and cognitive mapping skills.

Milestones in Everyday Mapping

| Year | Platform/Technology | Innovation | Impact |

| ~2000 | Garmin/TomTom GPS | Turn-by-turn consumer navigation | Transformed daily travel behavior |

| 2005 | Google Maps | Web-based interactive maps | Ubiquitous mapping platform |

| 2007 | Street View | Immersive ground-level imagery | Changed real estate, tourism, and privacy debates |

| 2008 | OpenStreetMap | User-edited maps | Democratized cartography |

| 2010s | Waze, AR maps | Real-time crowdsourced routing | Behavior-driven optimization of urban mobility |

Today’s maps are active companions. They anticipate needs, correct errors, suggest restaurants, track fitness, and locate friends. They no longer just describe space—they engineer experience. They follow us, learn from us, and, in subtle ways, guide our steps.

Yet these same tools open up deep philosophical and ethical questions about autonomy, privacy, and spatial justice. As we become ever more reliant on intelligent maps, we must ask: Who draws them? Who controls them? And what invisible lines are shaping the paths we walk?

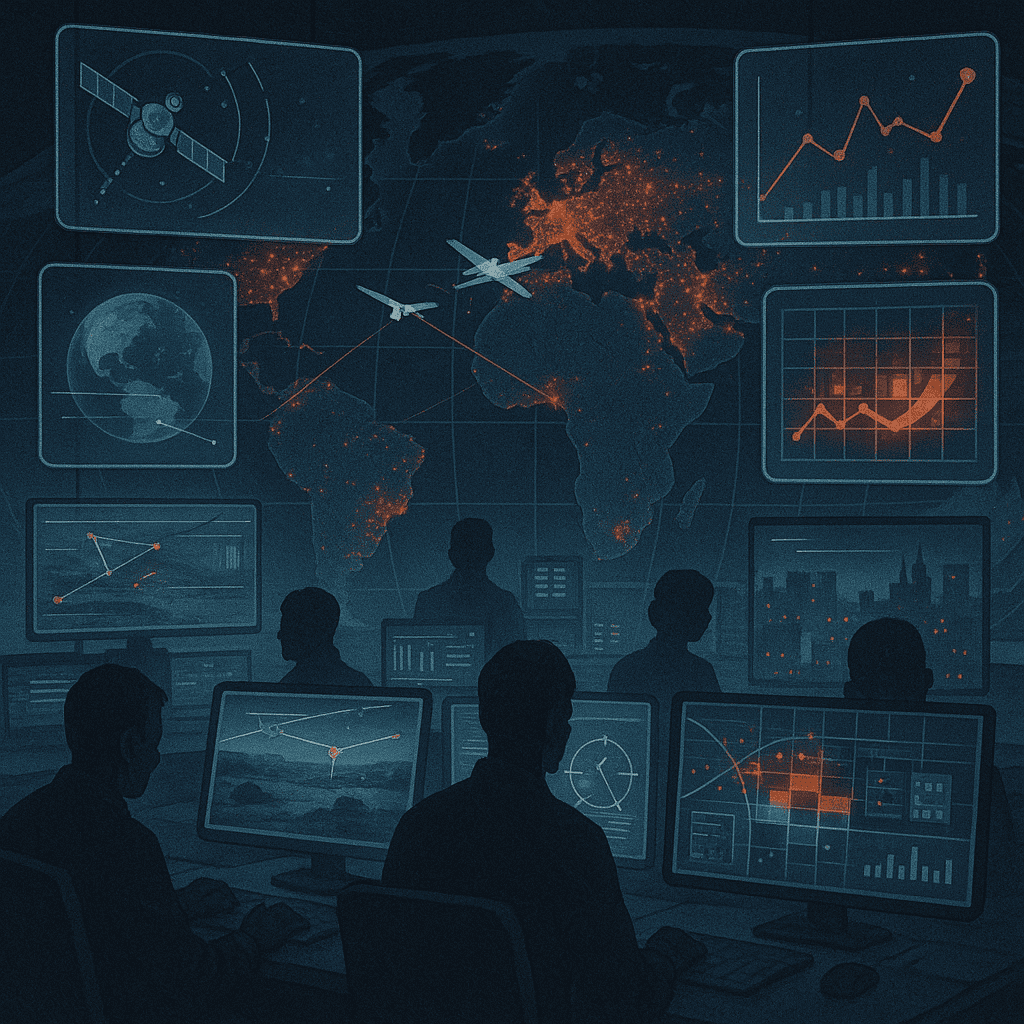

7. The Intelligence of Space – Geospatial Analytics and Surveillance

In the 21st century, mapping has moved beyond orientation and navigation. It has become a form of intelligence—a strategic resource as critical as energy or information. As billions of sensors, satellites, and smartphones continuously gather geospatial data, the resulting maps are no longer passive records of geography but real-time mirrors of global activity.

This new phase is defined by geospatial analytics: the ability to analyze spatial data to predict behavior, monitor environments, and exert influence across domains ranging from defense and agriculture to marketing and policing. Mapping has become surveillance, strategy, and simulation.

7.1. Government and Military Geointelligence

Modern militaries and intelligence agencies rely on highly advanced mapping systems to monitor terrain, track movement, and anticipate threats. Agencies like the U.S. National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), China’s Beidou Program, and the EU’s Copernicus Programme provide strategic decision-makers with continuous situational awareness.

Using synthetic aperture radar (SAR), hyperspectral imaging, and high-resolution satellite feeds, governments can observe vehicle patterns, identify crop failures, track wildfires, detect missile launches, or analyze troop deployments—even through cloud cover or at night.

This form of geospatial intelligence (GEOINT) has become an essential pillar of national security.

7.2. Corporate Mapping and Behavioral Targeting

Private corporations now wield geospatial power at planetary scale. Tech giants like Google, Apple, Amazon, and Facebook collect immense quantities of location-based data to optimize delivery routes, target ads, and analyze consumer behavior.

Retailers study foot traffic to plan store locations. Urban planners simulate pedestrian flow. Insurance companies assess flood risk. Delivery platforms calculate optimal timing and logistics. Data-driven maps are no longer just about space—they’re about economy, emotion, and intent.

This type of predictive cartography links location to psychology, transforming the map into a behavioral crystal ball.

7.3. Smart Cities and Urban Sensing

In “smart cities,” geospatial systems are embedded in the infrastructure itself. Street cameras, vehicle sensors, traffic lights, mobile apps, and environmental monitors all feed into urban dashboards that track everything from pollution to parking.

Mapping here becomes a real-time control system. It optimizes energy use, manages traffic congestion, predicts accidents, and automates public transport.

But this centralization of geospatial control raises critical issues around governance, equity, and autonomy. Who owns the city’s map? Who decides what gets mapped, and who remains invisible?

7.4. Crisis Mapping and Humanitarian Response

Geospatial intelligence is also a powerful tool for disaster response and humanitarian aid. Organizations like the UN, Red Cross, and Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT) use satellite imagery and on-the-ground reports to map earthquake zones, refugee camps, flood areas, and epidemic outbreaks.

Machine learning models can now detect building damage, predict migration flows, or locate vulnerable populations. In crises, maps become lifelines—prioritizing aid and saving lives.

7.5. Ethical Dilemmas and the Right to Be Unmapped

The increasing precision and ubiquity of mapping technology pose major ethical challenges. Mass surveillance, predictive policing, border enforcement, and facial recognition systems are all spatially driven. Protesters, dissidents, and marginalized communities may be tracked in real time.

There is growing concern over what scholars call the “weaponization of geography”—where the map becomes an instrument of domination rather than liberation. As mapping becomes ever more automated and opaque, the human right to privacy, movement, and spatial self-determination hangs in the balance.

Mapping Intelligence in the 21st Century

| Domain | Example | Function | Ethical Concern |

| Military | NGA satellite surveillance | Monitor enemy movements | Escalation and secrecy |

| Corporate | Google/Meta ad targeting | Behavioral prediction | Consent and profiling |

| Urban | Smart city dashboards | Optimize city services | Centralized control |

| Humanitarian | HOT Crisis Mapping | Disaster response | Accuracy, prioritization |

| Policing | Predictive crime maps | Resource allocation | Bias, civil liberties |

Today, the map is no longer merely a tool for humans—it is increasingly built by and for algorithms. It shapes markets, manages populations, influences elections, and programs daily life. Its intelligence can liberate or control, heal or harm.

As we move forward, the question is not just how to map the world—but how to do so ethically, equitably, and transparently. For in a world shaped by spatial data, the lines we draw—and the lines we choose not to draw—will define the future of freedom.

8. The Future of Mapping – Augmented Earth to Cosmic Charts

As cartography enters the next frontier, the boundaries of what a “map” is—and what it can do—are dissolving. No longer limited to two-dimensional depictions of physical terrain, maps are evolving into living, interactive, and intelligent platforms that encompass digital, biological, and cosmic spaces. We are moving beyond Earthbound geographies toward an era of augmented Earth, planetary modeling, and universal cartography.

Mapping the future means mapping the invisible, the dynamic, and the infinite.

8.1. Augmented Reality and the Spatial Web

With the development of augmented reality (AR) and mixed reality (MR) technologies, maps are breaking out of screens and entering physical space. Navigation apps now project directional arrows directly onto the world through smart glasses or phone cameras. Construction crews use AR overlays for underground infrastructure. Tourists receive real-time historical or cultural annotations as they walk.

Soon, digital layers of information—location-specific, personalized, and contextual—will exist everywhere, forming a “Spatial Web” that integrates cyberspace with the physical world. Maps will be interactive environments, not separate objects.

8.2. Living Maps – Ecosystems, Genomes, and Minds

The concept of mapping has expanded to include biological, cognitive, and systemic dimensions. Scientists now map genetic sequences (genomic cartography), neural connections (the connectome), and ecological networks. AI models help visualize the dynamic interactions of forests, oceans, and climate systems as living maps of Earth’s biosphere.

These maps are not static—they are processual, capturing change over time, predicting evolution, and revealing invisible interdependencies.

Maps of the future may model not just space but complex systems: pandemics, supply chains, food webs, and emotional flows.

8.3. Digital Twins and Planetary Simulation

Advances in computing power and sensor networks are enabling the creation of digital twins—virtual models of cities, factories, or even entire ecosystems that simulate conditions in real time. Projects like Destination Earth (DestinE) by the European Union aim to model the entire planet with unprecedented resolution for climate prediction and policy planning.

These simulations are effectively 4D maps—tracking not only location but change over time and projecting future scenarios. They offer new ways of steering collective decisions about sustainability, resilience, and survival.

8.4. Space Mapping and Cosmic Cartography

As humanity expands its presence beyond Earth, we are building the first true maps of the solar system and beyond. NASA, ESA, and other space agencies are mapping Mars, the Moon, asteroids, and exoplanets in high resolution. The James Webb Space Telescope is assembling the most detailed map of the early universe ever created—capturing light that has traveled for billions of years.

Cosmic cartography is redefining the scale of human inquiry. The “map of the known universe” is now a real scientific artifact, not a poetic metaphor.

Eventually, autonomous probes and AI explorers may chart the topography of exomoons, black hole accretion disks, or entire galactic clusters. The map, once centered on the sacred city or the imperial capital, will stretch across dimensions beyond human reach.

8.5. Ethical Futures – Mapping as Moral Design

As maps gain power and intelligence, the ethical stakes of cartography will rise. Future maps will not be neutral—they will embody values, priorities, and worldviews. They will influence climate action, resource distribution, disaster preparedness, and migration.

Thus, we must ask: who will design the maps of tomorrow? Will they reflect human dignity, environmental justice, and global cooperation? Or will they serve narrow interests and deepen inequalities?

A humanist cartography of the future must be transparent, participatory, and inclusive—drawing not just borders and roads, but paths to a shared and sustainable destiny.

Horizons of Future Mapping

| Domain | Technology | Map Type | Purpose |

| Urban Life | AR & Spatial Web | Immersive live overlays | Navigation, learning, accessibility |

| Bioscience | Genomics, Connectomics | Maps of life and mind | Medical & evolutionary insight |

| Earth Systems | Digital Twins | Planet-scale simulation | Climate resilience, policy planning |

| Space | Satellite telescopes, rovers | Cosmic and planetary maps | Exploration and research |

| Ethics | Participatory mapping platforms | Moral and political geographies | Justice and collective action |

Tomorrow’s maps will not just tell us where we are. They will help us decide who we want to be. They will guide not only our journeys, but our judgments.

In mapping the cosmos, we may ultimately rediscover our place within it—not as masters of all space, but as stewards of a fragile world in a vast and luminous universe.

Conclusion: Mapping Meaning – Humanity’s Evolving Mirror

From etched clay tablets to immersive augmented realities, the history of mapping is the history of how human beings make sense of space, power, and existence. Every map ever drawn is a mirror—reflecting not only terrain and topology, but the values, fears, hopes, and worldviews of those who made it.

Maps began as sacred symbols, aligning societies with the cosmos and the gods. They evolved into tools of navigation, conquest, science, and commerce. In the modern era, they became living data streams—shaping decisions, influencing behavior, and simulating futures. Today’s maps tell us what to eat, where to turn, who to trust, when to evacuate, and where we are most likely to thrive—or perish.

And yet, beneath all these transformations, the central function of the map remains: to locate us. In geography. In history. In relationship. In responsibility.

We now inhabit a planet whose every mountain, street, and forest has been charted, but whose moral and ecological boundaries remain perilously undefined. We have mapped the Moon and Mars, yet struggle to chart a sustainable future here on Earth. We navigate cities in seconds, yet often fail to see the invisible architectures of inequality, bias, or exclusion embedded in the digital maps we depend on.

The future of mapping will not be defined solely by new tools, but by new ethics. We must ask: What kinds of worlds are we building through the maps we design? Are they inclusive, transparent, and democratic? Or are they extractive, surveillant, and divisive?

A truly integrated, humanist cartography must marry precision with wisdom. It must guide without coercing, reveal without violating, and connect without controlling. It must honor not only the physical contours of the Earth, but the complex, living systems—natural and cultural—that give our world meaning.

In the end, the most important territory to map may not be land, sky, or sea, but the shifting frontiers of human consciousness, collaboration, and care. For to know our place in the universe is not merely to chart the stars—but to trace the paths we must take, together, toward a just and flourishing planet.