Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Name Is Misleading

Why “Humanism” may no longer be the best word for the moral vision we hold. - The Evolution of Human Superiority

How religious and psychological beliefs shaped a myth of human exceptionalism. - Recognizing Shared Sentience

The scientific evidence that animals think, feel, and suffer like we do. - Sacredness of Life: Philosophical and Religious Support

Traditions across history that affirmed the moral value of all living beings. - The Moral Truth Beyond Religion

How science reveals real ethical responsibilities without invoking the sacred. - Human-Centered Thinking and the Ego Illusion

Why species-level egocentrism must be outgrown like childhood ego. - A Broader Awakening: From Humanism to Creaturism

Freemasonry, Buddhism, Zen, and science all point toward a wider compassion. - The True Meaning of Humanism

To be truly human is to recognize and embrace the suffering and dignity of all creatures. - Bibliography

I. Introduction: The Name Is Misleading

We call it Humanism—a philosophy rooted in reason, compassion, and a commitment to the well-being of humanity. But that name, inherited from Renaissance thinkers and secular reformers, subtly betrays the limitations of its own origin. It suggests a world in which humans alone matter most, or matter categorically more than other forms of life. The name seems to set the boundaries of moral concern around the species Homo sapiens, as if we exist above or apart from the rest of the living world.

But if we are honest—scientifically honest, ethically honest—this is no longer tenable.

The deeper truth is that the moral vision we hold, if it is truly grounded in compassion and evidence, must go beyond humanity. It must extend its circle of empathy to other creatures—those that feel, fear, grieve, and love. This broader moral stance, while still called “Humanism,” is in fact something more expansive: a form of Creaturism, a worldview in which we recognize the shared condition of all sentient beings, not just humans.

This article reexamines the roots of humanism and reveals what it may one day become. For though we may still call it “Humanism,” this is its true meaning.

II. The Evolution of Human Superiority

The belief that humans are categorically superior to all other forms of life has deep roots in Western civilization. From the ancient Greeks through medieval Christendom and into modern secular thought, a persistent thread has portrayed the human being as the center of moral, spiritual, and intellectual concern.

In the Judeo-Christian tradition, this superiority is enshrined in scripture. The Book of Genesis declares that humans are made in the image of God and are given “dominion over the fish of the sea and the birds of the sky and every living thing that moves on the earth” (Genesis 1:26). Theologians such as Thomas Aquinas reinforced this notion by teaching that animals were created for human use, lacking reason and souls, and thus outside the sphere of moral obligation. In this view, humans possess eternal souls destined for Heaven, while animals are mere earthly bodies destined for decay.

Such beliefs offered comfort: the promise of life beyond death, a sense of being chosen, and the reassurance of a cosmic hierarchy in which humans stand near the top. But these ideas did not emerge from observation or empirical inquiry. They emerged from fear—fear of death, fear of meaninglessness, and fear of insignificance in the face of nature’s vastness. In psychological terms, they are defense mechanisms: symbolic shields against the anxiety of being finite, fragile, and mortal.

Secular scientific thinking, by contrast, begins with skepticism toward such untested assumptions. It questions the narrative that only humans matter because only humans live forever. Evolutionary biology, neuroscience, and psychology have revealed that all living creatures share a common ancestry and many biological capacities. Death is not a curse unique to some and escaped by others. It is a universal condition. What religious doctrines ascribe to divine privilege, the scientific mind recognizes as emotional projection—an understandable but unproven story told by mortal creatures who crave immortality and uniqueness.

As scholars such as Ernest Becker (The Denial of Death), Robert Sapolsky (Behave), and Yuval Harari (Sapiens) have shown, the longing to be special and to live forever is not evidence of truth, but evidence of our evolutionary and cultural psychology.

The myth of human superiority, therefore, is not a rational truth, but a tale born from our ancient fears.

III. Recognizing Shared Sentience

If the myth of human superiority is unscientific, what does science actually tell us about the lives of other creatures?

The answer is both simple and profound: many animals feel. They fear danger. They seek safety. They mourn loss. They experience joy, grief, and even love. These are not poetic projections, but increasingly documented facts grounded in neuroscience, ethology, and behavioral psychology.

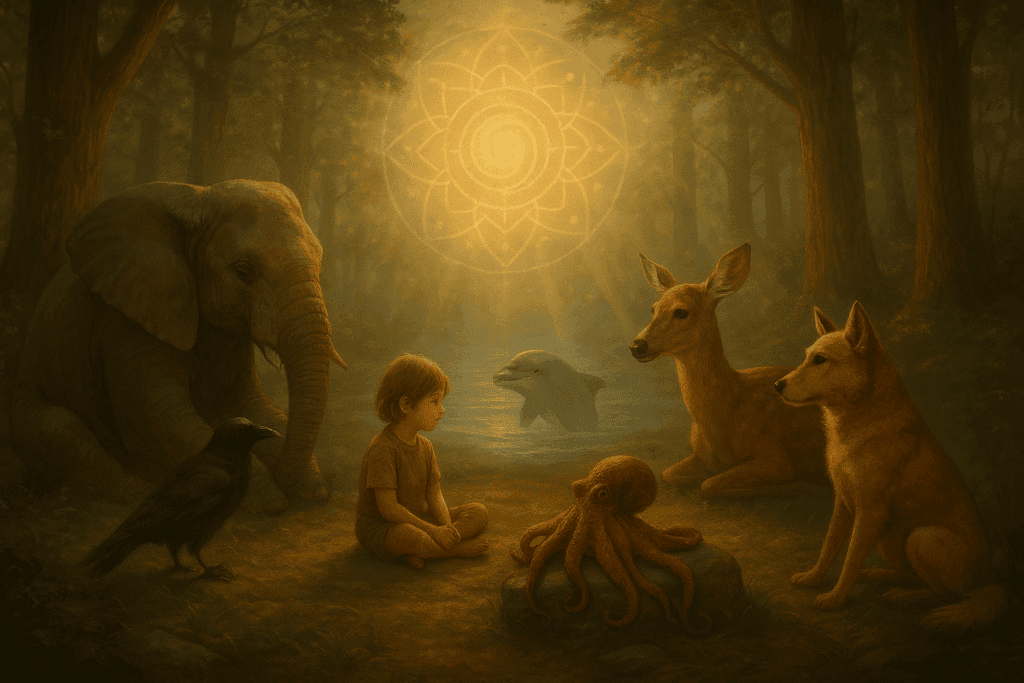

Elephants have been observed standing vigil over the bodies of their dead. Orcas and dolphins have been seen carrying their deceased calves for days. Dogs recognize and grieve the loss of their human companions. Crows hold “funeral-like” gatherings. Octopuses solve puzzles and show unique personalities. Great apes—chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas—display empathy, share food, reconcile after conflict, and learn from one another through imitation.

The traditional criteria we once used to separate ourselves from other species—language, tool use, emotion, planning, mourning—have all been found across a wide range of the animal kingdom.

Studies have confirmed that mammals, birds, and even some invertebrates possess central nervous systems and neurochemical structures that mirror those in humans associated with affective states like fear and pleasure. The hormone oxytocin, for instance—often called the “love hormone”—is found not just in humans but in dogs, rats, and many mammals, where it facilitates social bonding and trust.

Tests such as the “mirror self-recognition test,” while imperfect, have shown that certain animals possess forms of self-awareness. Others communicate in symbolic languages, anticipate future events, and exhibit what appears to be moral behavior—cooperation, altruism, and fairness.

Three leading sources on this subject are:

- Frans de Waal, Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are?

- Carl Safina, Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel

- Temple Grandin, Animals in Translation

From these and other studies, a new moral awareness has begun to emerge. It is no longer tenable to claim that animals are unfeeling automatons, mere background actors in a drama meant only for humans.

If sentience is the ability to experience subjective states such as pain, fear, desire, and joy, then many animals—perhaps most—are sentient. And if sentience is our moral benchmark, then our ethical concern cannot logically stop at the boundaries of our species.

To recognize the sentience of others is to recognize their claim upon our empathy.

IV. Sacredness of Life: Philosophical and Religious Support

Long before science began mapping the nervous systems of animals or measuring their cortisol levels, some thinkers and spiritual traditions intuited a deep moral unity among all living beings. Across cultures and centuries, a thread of thought has consistently challenged the human-centered worldview, insisting that the value of life is not reserved for humans alone.

Pythagoras and the Ancient Philosophers

The early Greek philosopher Pythagoras (6th century BCE) believed in the transmigration of souls, teaching that the same essence that inhabits a human being may dwell in animals as well. He was a proto-vegetarian, arguing that killing and eating animals was a form of spiritual impurity. In his school, abstaining from meat was not merely about health—it was an ethical and metaphysical stance affirming the kinship of all life.

Eastern Religions: Ahimsa and Rebirth

In Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, this kinship became a central doctrine. The Sanskrit word ahimsa—meaning non-violence or non-harming—is one of the oldest moral principles known to humankind. It arises from the belief in karma and rebirth: that every sentient being is subject to suffering, death, and the wheel of existence.

Jain monks and nuns, in particular, have gone to great lengths to avoid harming even the smallest forms of life, sweeping the ground before them to avoid stepping on insects, and wearing cloth masks to avoid inhaling unseen creatures. This may seem extreme, but it reflects a worldview in which the boundary between human and non-human is ethically irrelevant.

Buddhism, especially in its Mahayana and Zen forms, teaches that all sentient beings are capable of enlightenment, and that compassion toward all life is an essential aspect of liberation.

Western Mysticism and Christian Saints

While dominant Western theologies emphasized human dominion, dissenting voices occasionally emerged. Saint Francis of Assisi (1181–1226) preached to birds and befriended wolves, referring to the sun and moon as his siblings, the animals as his companions. In his Canticle of the Creatures, Francis expressed a cosmic humility rare in medieval Christianity.

Mystical strains of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam also carry elements of reverence for all life, although these have rarely shaped mainstream doctrine.

The Rise of Ethical Vegetarianism and Veganism

In more recent centuries, the moral case for animal welfare has found new footing in secular ethics. The 19th-century utilitarian Jeremy Bentham wrote:

“The question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?”

Building on that logic, modern ethicists like Peter Singer (Animal Liberation, 1975) and Tom Regan (The Case for Animal Rights, 1983) have argued that causing unnecessary suffering to sentient beings—regardless of species—is morally indefensible.

Vegetarians, vegans, animal rights activists, and many ordinary people today participate in this philosophical lineage, whether consciously or not. Their practices reflect a broadening circle of empathy, rooted in the ancient recognition that we are not alone in our capacity to suffer or to love.

These ethical traditions—religious and secular alike—point toward a profound insight: life matters, not because it is human, but because it is alive and aware.

V. The Moral Truth Beyond Religion

Religious traditions often anchor morality in the will of a god or the authority of sacred texts. But from a scientific humanist perspective, morality does not require divine decree. It emerges naturally from the lived experience of sentient beings.

A scientific worldview may not affirm the existence of sacredness in any absolute or supernatural sense. To science, no atom is holier than another, no species inherently more “divine.” However, science does observe the capacity for pain, fear, empathy, and flourishing across many forms of life. From this observation arises a powerful moral conclusion: unnecessary harm is real, and preventing it is good.

The moral truth science helps us uncover is not dictated from above—it is grounded in biology, psychology, and the evolutionary logic of empathy.

Pain is measurable. Suffering is observable. Cruelty has consequences not just for its victims but for the social fabric of any group that permits it. Compassion and cooperation, by contrast, support the flourishing of communities—human and non-human alike.

We do not need to claim that life is sacred in a metaphysical sense to believe that causing unnecessary suffering is wrong. As The Moral Compass, the Science Abbey article, articulates:

Morality is not a divine command, but an empirical reality: when sentient creatures suffer unnecessarily, there is harm—and harm is a condition we are capable of alleviating.

Neuroscience shows that animals and humans share key structures for processing pain (like the amygdala, insula, and anterior cingulate cortex) and emotions. Mirror neurons and emotional contagion suggest that empathy is not unique to humans. Rats will forgo chocolate to free a trapped companion. Dogs comfort crying humans. Elephants return to the bones of their dead.

From these facts, we can derive principles. One of the clearest is this:

Causing unnecessary suffering is cruel, and cruelty is wrong.

This isn’t a commandment from the heavens. It’s a truth revealed in the shared vulnerability of living creatures and the mutual benefit of compassion.

So while sacredness may remain a religious term, the imperative to treat sentient beings with kindness is not religious. It is rational. It is observable. And it is binding, not because a god says so—but because reality does.

VI. Human-Centered Thinking and the Ego Illusion

From the beginning of recorded thought, humans have placed themselves at the center of the cosmos. This egocentrism—philosophical, cultural, and psychological—has been one of the defining features of our species.

The Legacy of Anthropocentrism

We once believed that the Earth stood still while the Sun, Moon, and stars revolved around it. The geocentric model wasn’t just an astronomical claim; it was a moral one. It affirmed our centrality, our specialness, our proximity to divine intention.

Even after Copernicus and Galileo overturned that model, anthropocentrism endured. Enlightenment humanism, while a triumph of secular morality, still often operated within a framework that prioritized human reason, human progress, and human sovereignty above all else.

In modern times, this centering of ourselves persists:

- Eurocentrism declared European culture the pinnacle of civilization.

- Sino-centrism placed China at the heart of the world order.

- Nationalism, tribalism, and exceptionalism reflect a similar logic: we are special, and others are less so.

At the individual level, this pattern emerges in childhood. Developmental psychologist Jean Piaget showed that young children are naturally egocentric—not selfish, but cognitively unable to take another’s perspective. As we mature, we learn that others have minds like ours. This realization is the foundation of empathy.

Civilizations, like individuals, must undergo the same transformation. If we wish to be moral adults on a planetary scale, we must grow out of species-level egocentrism.

The Ego and Its Shadows

Psychologically, the human ego is a necessary tool for navigating the world. But it can become a prison. Narcissism and psychopathy are extreme expressions of the human-centered mind: a near-total absence of empathy, a view of others as means rather than ends.

When cultures reflect this psychology—when profit matters more than ecosystems, or comfort more than justice—they embody the same pathology at scale.

Even well-meaning humanism can fall into this trap. By calling ourselves the measure of all things, we risk excluding the majority of sentient life from moral concern.

The Illusion of Separateness

Many spiritual and philosophical traditions have attempted to transcend the ego. Buddhism, in particular, teaches that the self is an illusion—a constantly changing stream of sensations, perceptions, and consciousness. To cling to a fixed self is to suffer.

Zen Buddhism goes further still. Soto Zen, as taught by Dogen Zenji, emphasizes the interpenetration of self and world. In Genjokoan, Dogen writes,

“To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be enlightened by all things.”

In this view, there is no fixed line between “I” and “other.” There is only reality, arising together. Sentient and nonsentient, organic and inorganic, being and non-being—these dualities dissolve.

The scientific humanist can arrive at a similar conclusion through different means. Modern ecology, systems theory, and neuroscience all suggest that what we call “self” is an emergent phenomenon—real, but contingent. We are networks of relationships, patterns of energy and matter sustained by a world we do not control.

To extend moral concern only to “ourselves” is to misunderstand what we are.

VII. A Broader Awakening: From Humanism to Creaturism

Humanism was a noble awakening—one that affirmed reason over superstition, ethics over dogma, and human dignity over authoritarian power. But in a world where scientific understanding, ecological awareness, and moral empathy continue to evolve, humanism must itself awaken to something larger: a broader, deeper compassion for all sentient beings.

We might call this evolution Creaturism—not a new religion or ideology, but a recognition of kinship. A kinship grounded not in myth, but in the shared conditions of life: to live, to feel, to love, to suffer, and to die.

From Anthropocentric to Biospheric Ethics

The expansion from a human-centered ethic to a life-centered one is not unprecedented. It echoes a trajectory already visible in philosophy, spirituality, and science:

- Freemasonry, in its Enlightenment form, referred to a Supreme Being or Great Architect of the Universe, a metaphor for the higher order beyond human understanding. Yet this framework still anthropomorphized the cosmos—envisioning an intentional creator in the image of man.

- Buddhism, particularly Mahayana and Zen, goes further. It speaks not of a creator, but of interbeing—where all things are mutually dependent, co-arising, and equally empty of fixed identity. It does not stop at human concerns, but seeks the liberation of all sentient beings.

- Soto Zen, with its radical non-duality, transcends even the distinction between sentient and insentient. Mountains, rivers, and stars participate in awakening. Everything speaks the dharma.

- Scientific Humanism, in this light, may also continue its journey. It begins with rational ethics rooted in human welfare, but it can—and must—expand to embrace the welfare of life itself.

The Creaturist Outlook

A Creaturist humanism recognizes that suffering is not species-specific. It understands that pain is pain, love is love, fear is fear—whether in a child, a dog, a crow, or an elephant. It does not demand we equate all lives, but that we acknowledge their realness.

Such an outlook:

- Extends empathy to all beings that feel, especially those with demonstrable consciousness, awareness, and affect.

- Accepts death as a natural part of life, without needing to believe in immortal souls.

- Grounds moral responsibility not in divine command, but in scientific understanding and the lived experience of compassion.

- Upholds our unique human responsibilities—precisely because we are the ones most capable of recognizing and responding to suffering in others.

To awaken into Creaturism is not to renounce humanity—it is to fulfill it.

VIII. The True Meaning of Humanism

So what, then, is the true meaning of Humanism?

It is not merely a philosophy that exalts humanity above all else. Nor is it a secular replacement for religion built on the altar of rational self-regard. True humanism—if we allow it to fulfill its deepest potential—is an open door. A threshold. A bridge between our species-specific concerns and a more expansive ethic that honors life in all its complexity and kinship.

It is a moral stance rooted in evidence, empathy, and responsibility. It recognizes that human beings are not the center of the universe, but rather one expression of its vast, creative unfolding. That our capacity for reason, language, and culture does not entitle us to domination, but obliges us to stewardship and care.

This is not the end of Humanism, but its next chapter—a chapter we might one day call Creaturism. For now, we keep the name Humanism, out of continuity and convenience. But we must never forget its deeper implications.

When we say human, we must mean creature—feeling being, mortal being, relational being. When we speak of dignity, we must remember that dignity is not exclusive to us. And when we live out the values of compassion, justice, and freedom, we must do so not just for ourselves, but for all beings who suffer and strive, breathe and bleed, love and perish.

To be truly human is to stand in solidarity with all creatures.

To be truly wise is to see beyond the mirror of our own face.

To be truly good is to live as if all life mattered—because it does.

So let us continue to call our philosophy Humanism, if we must. But let us live it as something more. Let us remember that we, too, are creatures. And let our actions speak to a vision that embraces the world, not just our species.

Let us be humanists, in truth.

Let us be Creaturists, in heart.

Bibliography

Books and Articles

- Becker, Ernest. The Denial of Death. Free Press, 1973.

- Bentham, Jeremy. An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. 1789.

- Dogen, Eihei. Shobogenzo (esp. “Genjokoan” and “Busshō”). Various translations.

- de Waal, Frans. Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are? W. W. Norton, 2016.

- Grandin, Temple, and Catherine Johnson. Animals in Translation. Scribner, 2005.

- Harari, Yuval Noah. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Harper, 2015.

- Piaget, Jean. The Moral Judgment of the Child. Free Press, 1932.

- Regan, Tom. The Case for Animal Rights. University of California Press, 1983.

- Safina, Carl. Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel. Henry Holt, 2015.

- Sapolsky, Robert M. Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst. Penguin, 2017.

- Singer, Peter. Animal Liberation. New York Review Books, 1975.

Religious and Philosophical Texts

- The Bible, Genesis 1:26 (New Revised Standard Version or equivalent)

- The Dhammapada (various translations)

- The Bhagavad Gita, esp. chapters on karma and ahimsa

- Teachings of Mahavira (Jain scriptures)

- Canticle of the Creatures, St. Francis of Assisi

- The Moral Compass. Science Abbey, 2025. www.scienceabbey.com

Scientific Studies and Reports

- Panksepp, Jaak. “Affective Neuroscience of the Emotional BrainMind.” American Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 160, no. 5, 2003.

- Reiss, Diana, and Lori Marino. “Mirror Self-Recognition in the Bottlenose Dolphin.” PNAS, 2001.

- Bartal, Inbal Ben-Ami et al. “Empathy and Pro-Social Behavior in Rats.” Science, vol. 334, 2011.

Institutional and Ethical Resources

- The Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education (CCARE), Stanford University

- The Nonhuman Rights Project: www.nonhumanrights.org

- Jain Vegan Initiative: www.jainvegan.org