“To all teachers, known and unknown, who continue the endless transmission of the Buddha Way”

Inside Monastic Culture Series Part XII

Table of Contents

Introduction

- The Light of Zen: From Siddhartha to the Great Bright Pearl

Part I: Zen Crosses the Sea

- Zen Encounters the West: Early Contact and European Reception

- Zen Buddhism in the West

- Sidebar: Early Milestones of Zen in the West

Part II: Zen in America

- American Zen Institutions: The Founding of New Centers

- Key Japanese Masters Behind American Zen: Nishiari, Oka, Kishizawa

- Sidebar: Lineage Tree from Nishiari Bokusan to American Zen Centers

- A Circle of Transmission: Relationships Among Key Teachers

- Sidebar: Web of Soto Zen Lineage

- The Lay Movement: Sawaki Kōdō, Kōshō Uchiyama, Gudō Wafu Nishijima

- Emerging American Teachers: Katagiri, Kobun Chino, and Okumura

- Builders of American Zen: Daido Loori, Bernie Glassman, Joan Halifax

- Everyday Zen Leaders: Norman Fischer and Sojun Mel Weitsman

- Zen and the Arts: Tanahashi Kazuaki

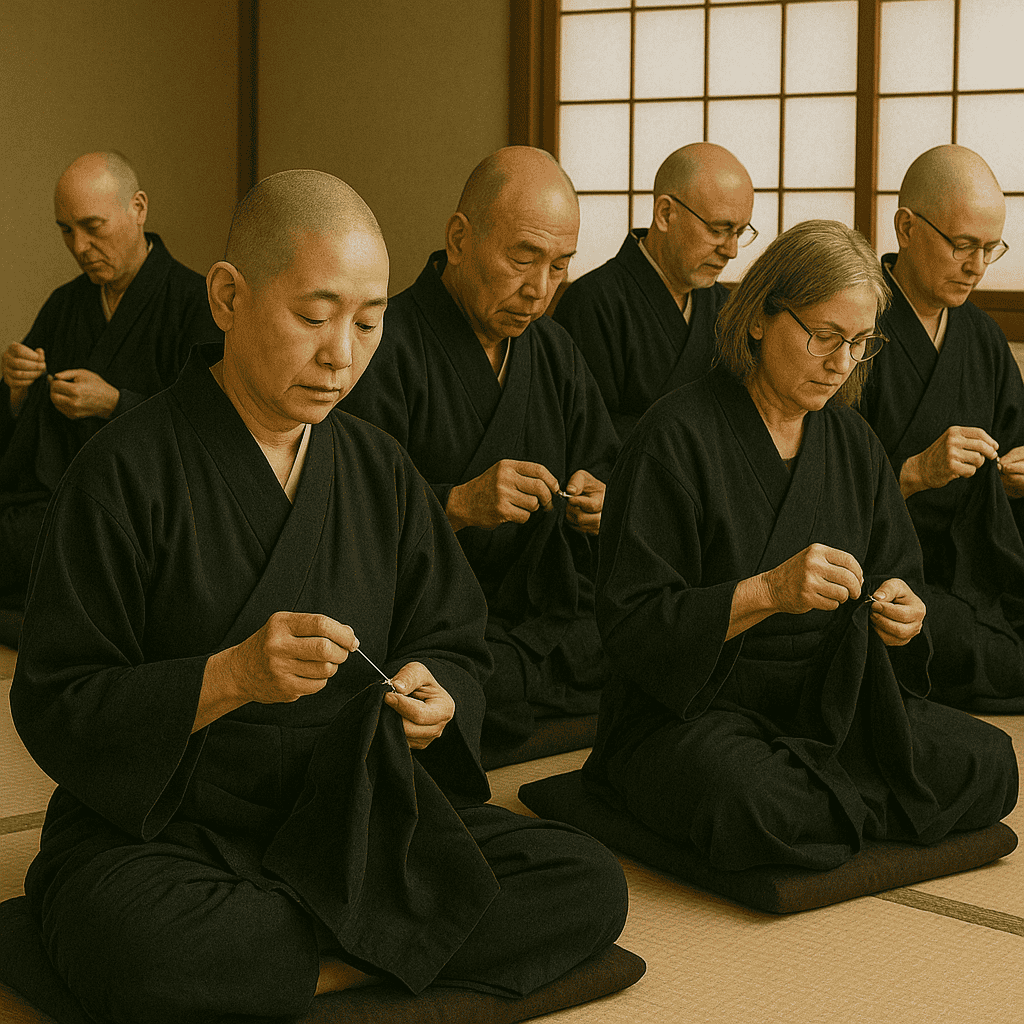

- Sewing the Buddha’s Robe: Tomoe Katagiri, Angie Boissevain, Yuko Okumura, Judy Putnam

- Sidebar: Symbolism of Robe Sewing

Part III: Zen’s Broader Harmonies

- Zen’s Relationships with Other Buddhist Traditions (Chan, Seon, Thiền, Tibetan, Thai Buddhism)

- Sidebar: Common Principles Across Buddhist Traditions

Part IV: Zen in Practice: Buildings, Life, and Transmission

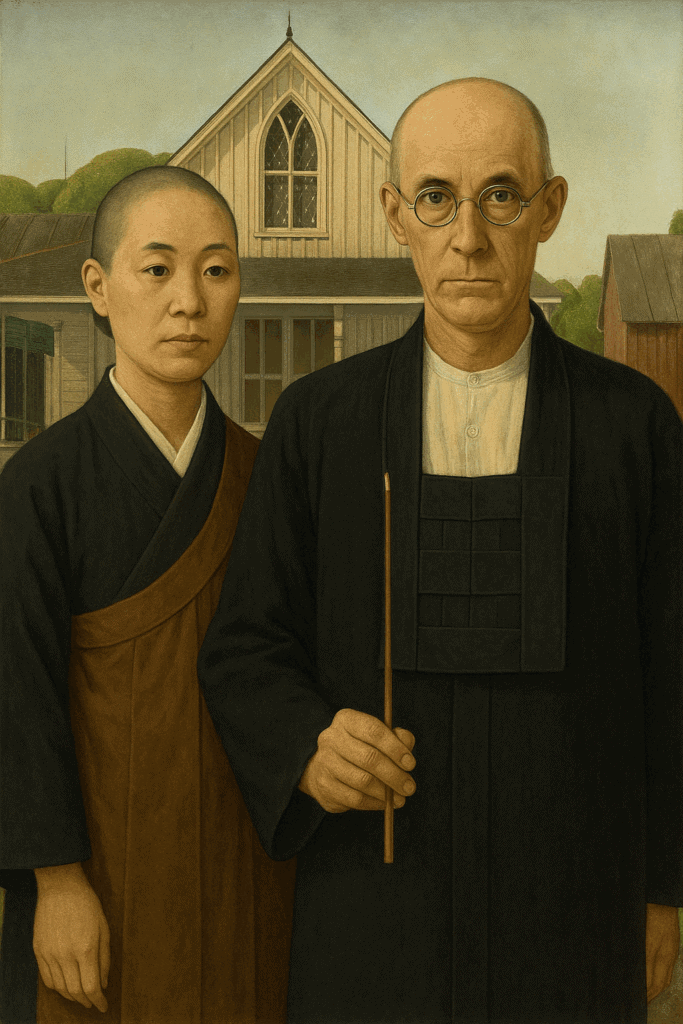

- American Zen Architecture and Temple Life

- Sidebar: Traditional Features of Zen Temples

- A Day in the Life of an American Soto Zen Priest

- Priesthood and the Path of Ordination

- Sidebar: Stages of Soto Zen Priest Training

Part V: Facing the Future

- Challenges and Adaptations: Zen in American Culture (Ethics, Lay Life, Psychotherapy, Tradition vs. Innovation)

- Sidebar: Key Challenges and Adaptations in American Zen

Conclusion and Reflection

- Conclusion: The Great Bright Pearl

- Epilogue: Carrying the Bright Pearl Forward

Introduction

The Light of Zen: From Siddhartha to the Great Bright Pearl

More than 2,500 years ago, in the shade of a fig tree on the banks of the Nerañjara River, a solitary seeker named Siddhartha Gautama sat down with a simple vow:

to awaken and to liberate all beings from suffering.

Through nights of fierce meditation and luminous clarity, he realized the profound truth of this existence: that life is fleeting, that all phenomena are without fixed self, and that liberation is possible through direct, compassionate understanding of reality itself.

This awakening gave rise to what we now call Buddhism — not merely a philosophy or a religion, but a living, evolving way of life rooted in stillness, inquiry, and compassion.

Centuries later, the flame of Siddhartha’s awakening crossed mountains and deserts, carried by the early Mahāyāna monks and mystics into China, where it merged with the spirit of Taoism to give birth to Chan.

From Chan arose the rugged, austere transmission of Zen — a tradition grounded not in scriptures or rituals alone, but in direct experience and wordless realization.

Bodhidharma, the First Ancestor of Zen in China, taught “a special transmission outside the scriptures, pointing directly to the human heart.”

Dongshan Liangjie, one of the great Chinese masters, spoke of the “Great Bright Pearl” — the shimmering, indivisible totality of life itself, ever-present but rarely seen.

In thirteenth-century Japan, the monk Eihei Dōgen crossed the stormy seas to China to retrieve the living mind of Zen and bring it home.

He taught that practice and enlightenment are one, and that to sit in meditation, wholeheartedly and without striving, is already to express the Buddha’s realization.

After him, Keizan Jōkin spread the Way among common people, ensuring that Zen’s light would not be confined to temples but would illuminate the lives of all who sought the truth.

Now, across oceans, generations, and countless moments of devotion and inquiry, the light of Zen shines in a new land.

American Zen, growing from these ancient roots, stands as both a continuation and a renewal: preserving the essential forms of practice while responding to the realities of a modern, diverse, dynamic world.

This article traces that journey — from Siddhartha’s quiet awakening, to Bodhidharma’s fierce resolve, to Dōgen’s sublime teachings, to the mountain monasteries, urban zendos, and quiet homes where Zen practitioners in America continue to sit, bow, breathe, and live the Buddha Way.

The light has never faded.

The Great Bright Pearl still shines — within you, within me, and within the ceaseless flow of all things.

Zen Encounters the West: Early Contact and European Reception

The introduction of Zen Buddhism to the Western world was a gradual and complex process, shaped by centuries of indirect encounters, scholarly curiosity, and cultural adaptation. For much of history, Western awareness of Zen and Buddhism more broadly remained fragmentary, filtered through the reports of missionaries, explorers, and colonial administrators.

The first glimpses of Buddhism reached Europe during the medieval period, carried by travelers such as Marco Polo, Jesuit missionaries like Francis Xavier, and scholars such as Matteo Ricci. Yet their understandings were often colored by Christian categories, interpreting Buddhist practices as forms of idolatry or exotic superstition.

A curious result of this early contact was the legend of Barlaam and Josaphat, a Christianized retelling of the Buddha’s life that led to the Buddha being canonized as a Christian saint in medieval Europe.

Sustained scholarly engagement with Asian religions began in the colonial period, particularly through the efforts of the British Empire in India. In 1784, Sir William Jones founded the Asiatic Society in Calcutta, establishing the first serious European study of Sanskrit texts.

This initiative inspired Oriental studies across Europe, influencing later movements such as Theosophy and American Transcendentalism, and setting the stage for deeper exploration of Buddhist philosophy.

In the nineteenth century, Buddhism slowly began to capture the Western imagination. Early European scholars such as Max Müller in Germany contributed to the broader study of Asian religions through monumental works like the Sacred Books of the East.

In France, Léon de Rosny studied and introduced Japanese Buddhism, while in Britain, diplomats and scholars including Ernest Satow and Arthur Waley expanded public knowledge of East Asian cultures, albeit with limited focus on Zen specifically.

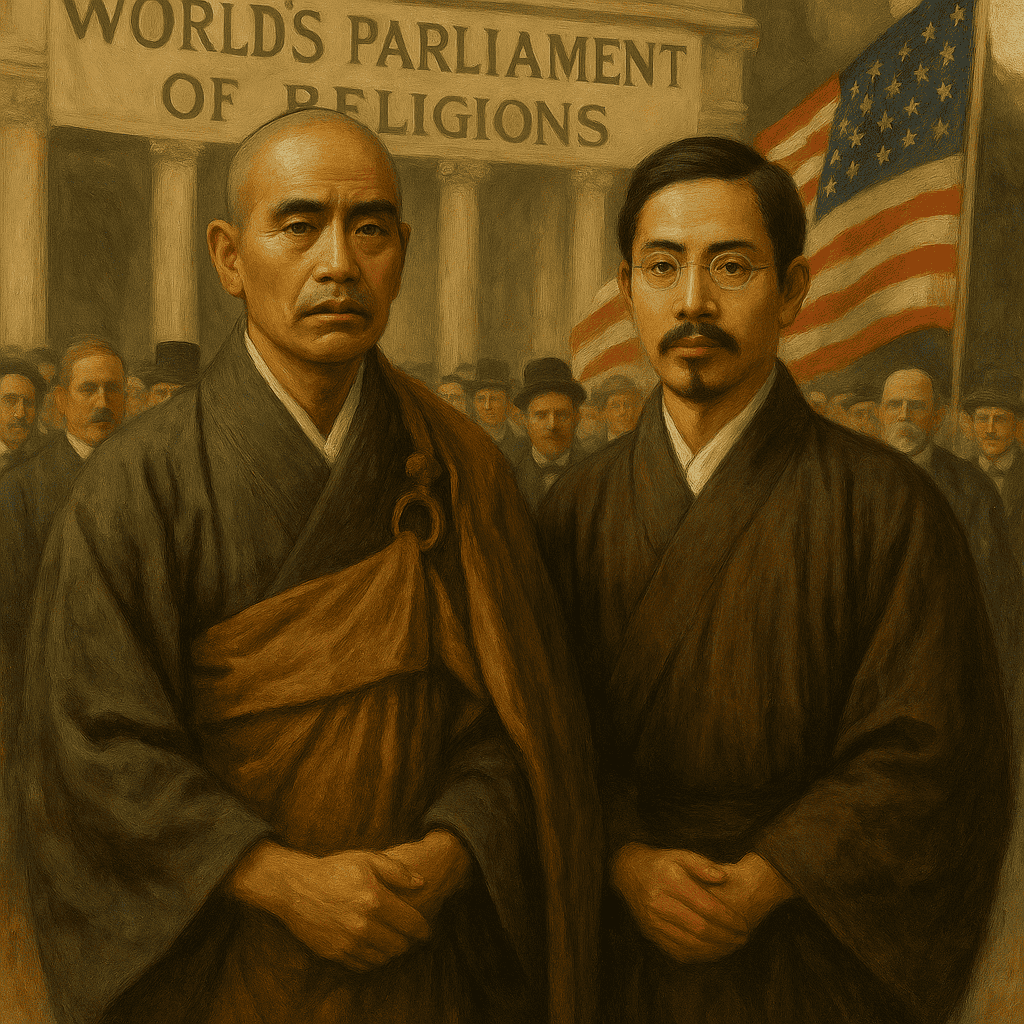

The first formal public presentation of Zen Buddhism in America occurred at the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893. Soyen Shaku, a Japanese Rinzai Zen master, addressed the assembly, accompanied by his disciple and translator, D. T. Suzuki. Although initially modest, this encounter planted seeds that would later flourish.

Following this event, important Buddhist texts became available in English:

- Paul Carus published The Gospel of Buddha (1894), a compilation intended for Western readers.

- W.Y. Evans-Wentz offered creative translations such as The Tibetan Book of the Dead (1927).

- Dwight Goddard compiled The Buddhist Bible (1932), introducing a broad American readership to Buddhist teachings.

D. T. Suzuki emerged as the most influential figure in shaping Western conceptions of Zen. Through works like Essays in Zen Buddhism (1927–1934), he presented Zen as an experiential, non-dogmatic spiritual path, compatible with modern individualism and democratic ideals.

Living at Engaku-ji monastery in Kamakura, Suzuki himself minimized many ritual elements of Zen in his presentation to Western audiences, focusing instead on meditation, kōan study, and direct transmission between master and disciple. This framing resonated with English-speaking readers but simplified the richer liturgical and communal aspects of traditional Zen practice.

In Britain, the first wave of Western Buddhist monastics also emerged. Charles Henry Allan Bennett (1872–1923), a former member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, traveled to Burma, where he was ordained as Ananda Metteyya in 1901. He founded the International Buddhist Society in London in 1903, promoting Theravāda teachings. In 1907, the Buddhist Society of Great Britain and Ireland was established, forming the first English Theravāda monastic sangha.

Christmas Humphreys (1901–1983), initially associated with the Theosophical Society, founded the Buddhist Lodge in London in 1924. It restructured as the independent Buddhist Society in 1943 and remains one of the oldest and largest Buddhist organizations in the West. Humphreys’ popular writings, such as Buddhism (1951), helped spread Buddhist thought to a general British audience.

In the United States, Zen’s influence expanded through figures like R. H. Blyth, who explored Zen aesthetics in Zen in English Literature and Oriental Classics (1942), and Alan Watts, whose charismatic teachings popularized Zen among American audiences during the 1950s and 60s.

Zen Buddhism in the West

While intellectual interest in Zen grew, deeper aspects of Zen monastic life remained largely unknown to early Western audiences. Suzuki’s portrayal of “pure Zen” emphasized meditation, kōan practice, and existential insight, while downplaying the extensive ritual practices embedded in Japanese monastic communities: daily and monthly memorial services, offerings to ancestors, ritual feeding of hungry ghosts, belief in spirits, karma, and the afterlife. In actual Zen monasteries, a monk’s life was as much structured by ritual form, etiquette, and collective labor as by meditation alone.

Following World War II, the American occupation of Japan and the broader opening of Japanese society to the world created new opportunities for exchange. Japanese Zen masters began traveling to Europe and North America, responding to a growing interest in direct, experiential spiritual practice.

Among the most influential were Shunryū Suzuki, who founded the San Francisco Zen Center and authored Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind (1970); Taizan Maezumi, founder of the Zen Center of Los Angeles; and Hakuun Yasutani, who trained a generation of American and European students.

Robert Aitken and Philip Kapleau, among Yasutani’s Western disciples, became the first recognized American Zen teachers. Kapleau’s The Three Pillars of Zen (1965) offered the first detailed English-language guide to the practice of zazen (seated meditation), making authentic Zen practice accessible to non-Japanese practitioners for the first time.

Zen’s influence extended beyond religious communities into the broader culture. The Beat Generation — writers such as Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg — embraced Zen as a philosophy of spiritual rebellion against conformity and materialism. However, their idealized image of Zen often overlooked the strict discipline and social restraint that characterized Japanese monastic life.

As Zen spread through literature, art, psychology, and popular spirituality, it adapted to the American context: emphasizing personal insight, egalitarian practice, and direct experience over hierarchical structures and ritual orthodoxy. This transformation reflects Zen’s historical resilience — its ability to evolve across cultures while preserving its essential spirit.

Today, Zen Buddhist monasticism in the West continues to grow and evolve. Rooted in ancient practice, yet responsive to modern sensibilities, it stands as a living bridge between East and West, tradition and innovation.

Milestones in the Early Western Encounter with Zen

| Year | Event | Key Figures |

| 1784 | Founding of the Asiatic Society | Sir William Jones |

| 1893 | World’s Parliament of Religions, Chicago | Anagarika Dharmapala, Soyen Shaku, D.T. Suzuki |

| 1901 | First British Buddhist monk ordained | Charles Henry Allan Bennett (Ananda Metteyya) |

| 1924 | Founding of the Buddhist Lodge, London | Christmas Humphreys |

| 1932 | Publication of The Buddhist Bible | Dwight Goddard |

| 1950s–60s | Rise of Zen in American counterculture | Alan Watts, Robert Aitken, Philip Kapleau |

The Founding of American Zen Centers: Establishing Lineages in the United States

The spread of Zen Buddhism in America after World War II was not merely a cultural phenomenon — it involved the deliberate establishment of formal Zen institutions, grounded in authentic monastic training and traditional Dharma transmission. This period witnessed the transplanting of established Japanese lineages, particularly those of the Sōtō and Rinzai schools, into American soil, alongside newer reform movements such as the Sanbō Kyōdan.

Shunryū Suzuki and the San Francisco Zen Center

One of the most influential figures in the establishment of Zen practice in America was Shunryū Suzuki (1904–1971), a Sōtō Zen priest trained at Eihei-ji, the head temple founded by Eihei Dōgen in the thirteenth century. Arriving in San Francisco in 1959 to serve a Japanese-American congregation, Suzuki quickly recognized the spiritual hunger of American seekers beyond the immigrant community.

In 1962, Suzuki formally founded the San Francisco Zen Center (SFZC), which soon became a central hub for American Zen practice. Under his guidance, the SFZC emphasized zazen (seated meditation) as the heart of training, adapted the traditional monastic schedule for lay practitioners, and established formal practice periods and sesshin (intensive retreats).

Suzuki’s writings, especially Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind (1970), became foundational texts for Western Zen practitioners. His quiet, patient transmission of Sōtō Zen helped establish a lineage that continues to thrive, with affiliated practice centers such as Tassajara Zen Mountain Center (the first Zen training monastery outside Asia, founded in 1967) and Green Gulch Farm.

Taizan Maezumi and the Zen Center of Los Angeles

Another major figure was Taizan Maezumi (1931–1995), a Sōtō priest also trained at Eihei-ji, who additionally received inka (formal recognition) in the Rinzai and Sanbō Kyōdan lineages. Maezumi arrived in Los Angeles in 1956 and initially served the Japanese-American community, but soon began teaching Western students.

In 1967, he founded the Zen Center of Los Angeles (ZCLA), establishing a rigorous training program that combined Sōtō zazen practice with kōan study — an innovative blending of traditional methods across lineages. Through his many Dharma heirs, Maezumi’s influence expanded nationally and internationally, founding what came to be known as the White Plum Asanga network of Zen teachers.

Maezumi’s adaptation of the monastic training environment to urban lay life set a model for many later Zen centers across the United States.

Hakuun Yasutani and the Sanbō Kyōdan Lineage

A distinct contribution to American Zen came through Hakuun Yasutani (1885–1973), founder of the Sanbō Kyōdan (Harada-Yasutani school). A reformer within Sōtō Zen, Yasutani emphasized the combination of rigorous kōan training with the foundations of shikantaza (“just sitting”) practice. His approach was intended to cut through the complacency he perceived in institutionalized Japanese Zen.

Yasutani’s influence in America came through his students, notably Philip Kapleau and Robert Aitken:

- Philip Kapleau (1912–2004) trained intensively with Yasutani and compiled The Three Pillars of Zen (1965), the first major practical manual of Zen meditation in English.

- Robert Aitken (1917–2010) founded the Diamond Sangha in Hawaii and authored many accessible works on Zen practice.

Sanbō Kyōdan-trained teachers helped establish small, independent Zen centers across North America, emphasizing direct experience, accessible instruction, and integration into lay life.

Rinzai Zen in America

While Sōtō Zen gained the largest presence, Rinzai Zen also established a foothold. Early Rinzai teachers such as Eido Tai Shimano (1932–2018), founder of the New York Zendo Shobo-ji (1968), and Omori Sogen Roshi (1904–1994), who influenced martial arts and calligraphy circles, brought traditional Rinzai training methods to American practitioners.

Rinzai practice, with its focus on intensive kōan study and strong master-disciple dynamics, appealed to those drawn to a more structured and confrontational path. However, the growth of Rinzai institutions in America remained more limited compared to the wider spread of Sōtō and hybrid lineages.

A New Landscape for Zen

By the 1970s, Zen centers and affiliated practice communities had appeared across the United States — in California, New York, Hawaii, and beyond. Some, like the San Francisco Zen Center, developed into large residential communities with monastic training tracks; others remained small urban temples or rural retreats.

Zen Buddhism in America thus evolved not as a replication of Japanese monastic life, but as an adaptation — maintaining the essential disciplines of meditation, mindfulness, and ethical living, while responding creatively to the conditions of American culture.

Through patient effort, formal transmission, and cultural adaptation, Zen found firm roots in the West — establishing living lineages that continue to grow, flourish, and evolve.

Founders of the Modern Soto Tradition: Japanese Zen Teachers Who Shaped American Zen

The flourishing of Zen Buddhism in the West, particularly in America, rests not only on the efforts of pioneering teachers abroad but also on the deep foundations laid by modern Japanese Soto Zen masters. During the Meiji period (1868–1912) and into the early twentieth century, a remarkable generation of scholars and practitioners revitalized the Soto tradition, clarified the teachings of Eihei Dōgen, and transmitted a living spirit of practice that would eventually find new soil in the Western world.

Among the most important of these figures are Nishiari Bokusan, Oka Sōtan, and Kishizawa Ian — teachers whose influence shaped the education of later masters such as Shunryū Suzuki, and through him, the early development of Zen in America.

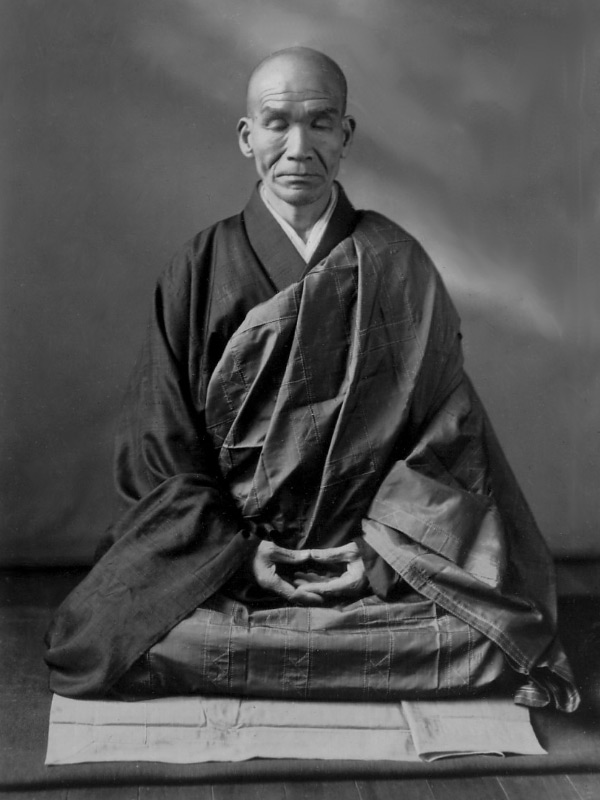

Nishiari Bokusan (1821–1910)

Nishiari Bokusan stands as a towering figure in the revival of Soto Zen during the Meiji period. At a time when Buddhism in Japan faced severe government suppression and internal fragmentation, Nishiari rose to prominence as a scholar, administrator, and teacher. He served as abbot of Sōji-ji, one of Soto Zen’s two head temples, and for a period as chief abbot (kanchō) of the entire Soto school.

Nishiari is best remembered for his scholarship on Dōgen’s Shōbōgenzō (“Treasury of the True Dharma Eye”), a work that had fallen into relative neglect. Through his lectures, writings, and commentaries — particularly the influential Shōbōgenzō Keiteki — he reestablished the centrality of Dōgen’s vision in Soto Zen thought and training.

Beyond scholarship, Nishiari’s true legacy lay in his students. Among them were Oka Sōtan and Kishizawa Ian, both of whom carried his revitalized spirit into the twentieth century and helped lay the groundwork for Soto Zen’s transmission to the West.

Oka Sōtan (1860–1921)

Oka Sōtan was a direct disciple of Nishiari Bokusan and one of the most respected Soto Zen teachers of his time. He became the first abbot of Antai-ji, a temple originally founded in 1923 as a scholarly monastery for the study of the Shōbōgenzō.

As a teacher, Oka Sōtan emphasized both scholarship and sincere zazen practice. He trained many figures who would shape modern Zen, including Kishizawa Ian, Kōdō Sawaki, Harada Sōgaku, and Gyokujun Sō-on — the latter being the teacher of Shunryū Suzuki.

Shunryū Suzuki later praised Oka Sōtan’s influence, regarding him as a “source of power” for many of the senior priests whom he respected. Through his emphasis on a grounded, integrated practice of study and meditation, Oka Sōtan helped preserve the living tradition of Soto Zen through a period of rapid modernization and societal change.

Kishizawa Ian (1865–1955)

Perhaps the leading interpreter of the Shōbōgenzō in the early twentieth century, Kishizawa Ian inherited the scholarly and spiritual lineage of both Nishiari and Oka Sōtan. Initially trained as a secular schoolteacher, Kishizawa entered monastic life in his thirties under Nishiari Bokusan, receiving dharma transmission at age thirty-six.

Kishizawa served as the third abbot of Antai-ji and as an official lecturer on the Shōbōgenzō at Eihei-ji, Dōgen’s original monastery. He was renowned for his intensive public lectures on Dōgen’s work, and over decades he published a monumental twenty-four-volume commentary entitled Shōbōgenzō Zenko — still one of the most extensive commentaries ever produced.

In the 1930s, Shunryū Suzuki became Kishizawa’s attendant at Eihei-ji, beginning a long association that profoundly shaped Suzuki’s understanding of Zen. Even after Suzuki returned to his family temple, he continued to commute regularly to study with Kishizawa until the latter’s death in 1955 — just a few years before Suzuki himself departed for America.

Through his scholarship and teaching, Kishizawa helped ensure that Dōgen’s profound but difficult writings remained at the heart of Soto Zen education. His students and dharma heirs, among them Kōdō Sawaki and Eko Hashimoto, would become key figures in the later global spread of Zen.

Legacy

The combined efforts of Nishiari Bokusan, Oka Sōtan, and Kishizawa Ian revitalized Soto Zen during a critical period of its history and provided the doctrinal clarity and living transmission that enabled later teachers, such as Shunryū Suzuki, to bring an authentic Zen practice to the West.

Their influence remains quietly present in every Zen center that emphasizes sincere zazen, the study of the Buddha Way, and the deep trust that realization is found not elsewhere but in the direct experience of everyday life.

Lineages from Nishiari Bokusan to the San Francisco Zen Center

- Nishiari Bokusan (1821–1910)

↳ Revitalized Soto Zen doctrine and Shōbōgenzō scholarship during the Meiji period. - Oka Sōtan (1860–1921)

↳ Disciple of Nishiari; emphasized study and zazen practice; first abbot of Antai-ji. - Kishizawa Ian (1865–1955)

↳ Disciple of Oka and Nishiari; leading interpreter of Dōgen’s Shōbōgenzō; teacher of Shunryū Suzuki. - Shunryū Suzuki (1904–1971)

↳ Disciple of Gyokujun Sō-on and long-time student of Kishizawa Ian; founder of the San Francisco Zen Center (Founded 1962).

The Tree:

- Nishiari Bokusan is the common root of all these figures.

- Oka Sōtan passed on a practical and scholar-practitioner Zen.

- Kishizawa Ian passed on a scholarly, deeply Dōgen-centered Zen, influencing Suzuki.

- Sawaki and Hashimoto, through Uchiyama, Nishijima, and others, created modern lay-focused Zen.

- Harada and Yasutani initiated the cross-style blending of shikantaza and kōan training.

- Shunryū Suzuki, Dainin Katagiri, Taizan Maezumi, and Kobun Chino spread Soto Zen formally and creatively across America.

The Lay Movement in Modern Zen: Sawaki, Uchiyama, and Nishijima

While many early twentieth-century Zen teachers worked within traditional temple structures, a distinctive movement also emerged — a return to pure zazen, accessible beyond the monastic walls. Three figures in particular shaped this lay-centered revitalization: Kōdō Sawaki, Kōshō Uchiyama, and Gudō Wafu Nishijima. Their lives and teachings helped to redefine Soto Zen practice for modern practitioners, both in Japan and abroad.

Kōdō Sawaki (1880–1965)

Kōdō Sawaki is remembered as one of the most influential Zen masters of the modern era. Often called “Kōdō the Homeless” because he refused to settle as abbot of any one temple, Sawaki traveled across Japan teaching shikantaza — “just sitting” — to monks, laypeople, workers, and students alike.

A dharma heir in the lineage of Oka Sōtan, Sawaki emphasized a return to the heart of Dōgen’s teaching: sitting meditation without attachment to rituals, titles, or hierarchies. Although he taught within the Soto Sect, his spirit was independent, and he critiqued the complacency and bureaucratic tendencies of institutionalized Zen. His bold, direct style made a lasting impression on generations of practitioners.

Sawaki never sought fame, yet he left a profound legacy through his students, especially Kōshō Uchiyama and through his influence on figures like Gudō Wafu Nishijima and Taisen Deshimaru.

Kōshō Uchiyama (1912–1998)

Kōshō Uchiyama, Sawaki’s closest disciple and dharma heir, further developed and clarified the spirit of lay-centered zazen practice. Originally a scholar of Western philosophy and a writer of poetry, Uchiyama ordained under Sawaki after feeling deeply drawn to the simplicity and universality of Zen.

After Sawaki’s death in 1965, Uchiyama became abbot of Antai-ji, transforming it into a center of rigorous zazen training. He is best known for his articulate, accessible teachings, which brought Dōgen’s principles to a broad audience without dilution. His important works, such as Opening the Hand of Thought and How to Cook Your Life, emphasize zazen as the wholehearted practice of opening, letting go, and living with compassion and clarity.

Through his disciple Shohaku Okumura and others, Uchiyama’s approach to Zen has reached practitioners across the globe, especially in North America.

Gudō Wafu Nishijima (1919–2014)

Gudō Wafu Nishijima represents another vital thread in the modern lay Zen movement. Originally trained as a lawyer and bureaucrat, Nishijima began serious zazen practice under the influence of Kōdō Sawaki and eventually received dharma transmission from Rempo Niwa, the 77th abbot of Eihei-ji.

Nishijima was particularly concerned with articulating Dōgen’s teachings in clear, philosophical terms. He interpreted Dōgen’s zazen not as mystical or religious, but as a direct practice of maintaining balance in body and mind — what he called “action in reality.” Nishijima emphasized the importance of bending the spine upright during sitting and considered zazen the source of authentic clarity, ethics, and wisdom.

Nishijima also produced English translations of Dōgen’s major works, including Shōbōgenzō, and mentored a generation of Western students, promoting independent Zen communities outside formal temple systems.

Legacy

Through the pioneering efforts of Sawaki, Uchiyama, and Nishijima, Soto Zen in the modern world rediscovered its original simplicity: a life grounded in direct sitting, without attachment to status, ritual, or metaphysical speculation. Their influence remains alive in the many Western Zen communities today that emphasize everyday practice, openness, and non-clinging as the living heart of the Buddha Way.

Bridging the Ocean: Katagiri, Kobun, and Okumura in American Zen

As the seeds of Soto Zen took root in American soil during the mid-twentieth century, a new generation of Japanese teachers arrived to guide its growth. Building on the deep practice of their own teachers — and adapting skillfully to the conditions of Western life — figures such as Dainin Katagiri, Kobun Chino Otogawa, and Shohaku Okumura have played crucial roles in the establishment of a distinctly American Zen.

Dainin Katagiri (1928–1990)

Dainin Katagiri, a disciple and dharma brother of Shunryū Suzuki, was one of the first Japanese Zen masters to settle permanently in the United States. Originally trained at Eihei-ji and through the traditional Soto monastery system, Katagiri first assisted Suzuki at the San Francisco Zen Center before founding his own community in Minnesota.

In 1972, Katagiri established the Minnesota Zen Meditation Center in Minneapolis, creating one of the first major Zen centers outside the West Coast. Later, he also founded Hokyoji Zen Practice Community in rural Minnesota, emphasizing a monastic-style training environment.

Katagiri’s teachings, collected in books such as Returning to Silence and Each Moment Is the Universe, focus on the simple, earnest practice of Zen in daily life. With great humility and gentleness, Katagiri helped show that the true spirit of Zen could thrive far from its Japanese roots — even amid the snows of the American Midwest.

Kobun Chino Otogawa (1938–2002)

Kobun Chino Otogawa was a unique and beloved figure in the transmission of Zen to the West. Born into a family with strong Buddhist and Shugendo traditions, Kobun trained at Eihei-ji and under several prominent teachers before moving to the United States in the 1960s at the request of Shunryū Suzuki.

Unlike more formal instructors, Kobun’s style was poetic, intuitive, and often spontaneous. He resonated especially with artists, musicians, and seekers of the American counterculture, becoming a spiritual advisor to communities in California and Colorado. Among his many contributions, Kobun helped found Haiku Zendo (which later became Jikoji Zen Center) and Haiku-ji.

Kobun’s influence also extended unexpectedly into the world of technology and creativity. He served for a time as spiritual teacher to Steve Jobs, founder of Apple Inc., exemplifying how Zen’s quiet presence found new expression in modern innovation.

Kobun’s teachings emphasized openness, compassion, and trust in the living moment. His tragic death in 2002, while attempting to save his daughter from drowning, was mourned by spiritual communities across the world — a testament to his profound impact.

Shohaku Okumura (b. 1948)

Shohaku Okumura, one of the leading living Soto Zen teachers in the world, trained under Kōshō Uchiyama at Antai-ji. Deeply influenced by Uchiyama’s clear and uncompromising presentation of shikantaza (“just sitting”), Okumura has dedicated his life to transmitting the heart of Dōgen’s teachings to an international audience.

After ordination, Okumura moved to the United States, where he co-founded the Minnesota Zen Meditation Center alongside Dainin Katagiri and later founded the Sanshin Zen Community in Bloomington, Indiana. His translations and commentaries, including Realizing Genjokoan and Living by Vow, have become essential guides for English-speaking practitioners.

Okumura is known for his careful, faithful translation of Dōgen’s difficult writings and his emphasis on zazen not as a tool for attainment but as the complete expression of the Buddha Way itself.

Legacy

Dainin Katagiri, Kobun Chino and Shohaku Okumura, among others, have helped weave Soto Zen into the fabric of American life — bringing both faithful transmission and creative adaptation, and ensuring that Dōgen’s vision of practice-realization would continue to unfold across continents and generations.

The Builders of American Zen Institutions: John Daido Loori, Bernie Glassman, and Joan Halifax

The maturation of Zen in America was carried forward by a new generation of practitioners — students of the early Japanese masters — who built institutions, reinterpreted practice for American life, and brought Zen into dialogue with art, activism, and psychology.

John Daido Loori (1931–2009)

John Daido Loori was a student of Taizan Maezumi and a pivotal figure in the establishment of Zen monasticism in America. Originally a professional photographer, Loori came to Zen through a deep appreciation for the expressive, non-conceptual nature of artistic creation.

He received dharma transmission from Maezumi and founded Zen Mountain Monastery (ZMM) in Mount Tremper, New York, in 1980 — creating a full residential training monastery modeled after traditional Japanese Zen temples. Loori integrated the arts, ethics, and environmental stewardship into monastic life, believing that the creative act was itself an expression of the Buddha Way. His works, such as The Eight Gates of Zen and The Zen of Creativity, continue to inspire practitioners.

Genzan Quennell, one of the senior successors of Loori’s lineage, continues to carry forward this spirit of integrated practice, ensuring that formal Zen training remains vibrant and accessible.

Bernie Glassman (1939–2018)

Bernie Glassman, another senior dharma heir of Maezumi, transformed the landscape of American Zen through his radical emphasis on engaged Buddhism. After receiving transmission, Glassman founded the Zen Peacemaker Order, combining traditional Zen training with social action, interfaith dialogue, and humanitarian work.

He pioneered “street retreats” — practicing Zen among the homeless — and established innovative projects such as the Greyston Bakery in New York, providing employment to marginalized communities. Glassman’s view that true Zen must meet the world with compassion and creativity helped redefine American Soto Zen in the late twentieth century.

Joan Halifax (b. 1942)

Roshi Joan Halifax, initially a student of Glassman, is a dharma heir and one of the foremost figures in contemporary engaged Buddhism. Founder and abbess of Upaya Zen Center in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Halifax integrates Zen training with end-of-life care, neuroscience, and social service.

Her teachings emphasize compassionate action, mindful death and dying, and the interconnection of all beings. Through her work, she has brought Zen into fields such as hospice care, activism, and medical ethics — expanding the bodhisattva vow into modern professional and personal spheres.

Living the Practice: Zoketsu Norman Fischer and Sojun Mel Weitsman

As American Zen matured, many students of Shunryū Suzuki and his lineage took up leadership, weaving traditional practice with a distinctly American voice — emphasizing lay life, community, and inclusivity.

Sojun Mel Weitsman (1929–2021)

Sojun Mel Weitsman was a close student of Shunryū Suzuki, who ordained him as a priest and entrusted him with helping establish Zen practice on the West Coast. Weitsman founded the Berkeley Zen Center in 1967, one of the oldest continuously operating lay-oriented Zen centers in America.

Known for his humility, steadiness, and deep devotion to simple practice, Weitsman embodied a spirit of Zen that prioritized ordinary mind — the cultivation of awakening through everyday life, community work, and sincere zazen. His leadership quietly shaped generations of practitioners in the Suzuki Roshi tradition.

Zoketsu Norman Fischer (b. 1946)

Norman Fischer, a former abbot of the San Francisco Zen Center, represents a generation of American-born Zen priests who skillfully adapted Zen practice to contemporary needs. Trained under Suzuki Roshi’s successors, Fischer emphasized the integration of Zen into family life, poetry, education, and social activism.

Fischer is the founder of the Everyday Zen Foundation, which promotes lay practice and socially engaged Buddhism. He is widely known for his accessible teachings and poetry, with works such as Training in Compassion and The World Could Be Otherwise, blending traditional Zen with practical mindfulness for daily life.

The Art of Zen: Tanahashi Kazuaki

While many teachers brought Soto Zen into institutional and social forms, others carried it into the arts — embodying Zen through creativity and aesthetics.

Tanahashi Kazuaki (b. 1933)

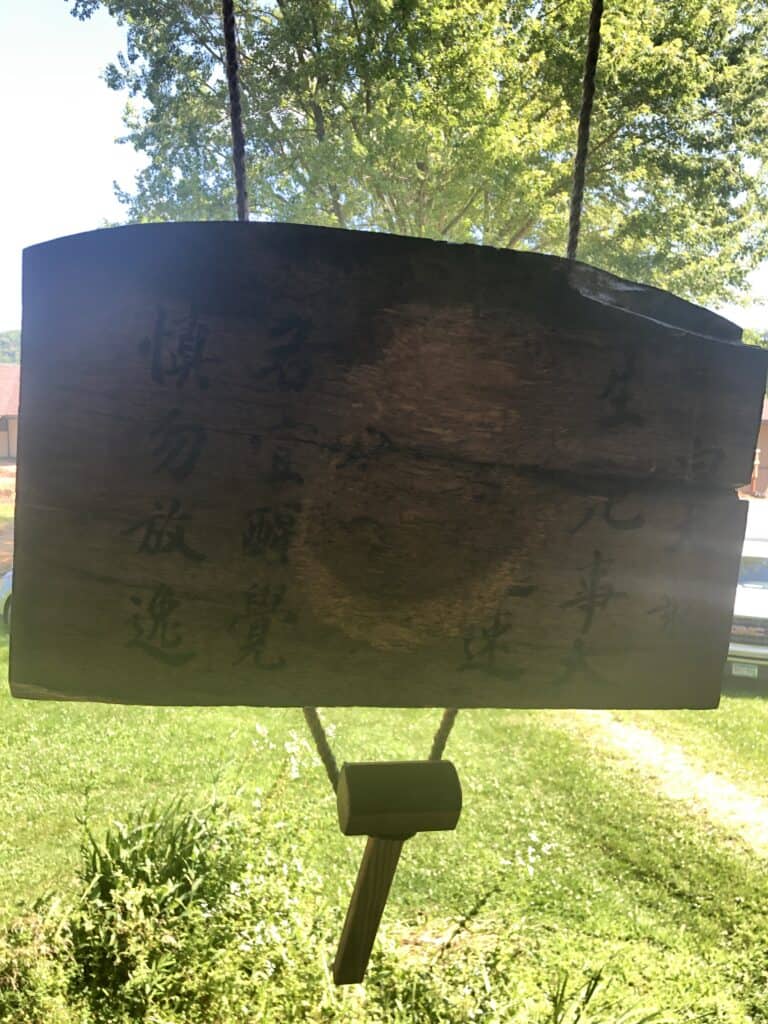

Kazuaki Tanahashi is a renowned calligrapher, translator, and artist who has been instrumental in bringing Dōgen’s writings and Zen aesthetics to a Western audience. Born in Japan and trained in classical East Asian arts, Tanahashi moved to the United States in the 1970s, where he became a bridge between cultures.

He is best known for his vivid “one-stroke” calligraphy, a dynamic expression of the Zen spirit of immediacy and freedom. As a scholar, Tanahashi produced major translations of Dōgen’s works, including Moon in a Dewdrop and Treasury of the True Dharma Eye, helping make these complex teachings accessible to English readers.

Through his art, translations, and teaching, Tanahashi preserves the living beauty of Zen while expressing it freshly for a global culture — a dynamic reminder that Zen is not confined to monasteries but flows through all aspects of life and creativity.

Legacy

Together, the work of Daido Loori, Bernie Glassman, Joan Halifax, Norman Fischer, Mel Weitsman, and Kazuaki Tanahashi demonstrates the many vibrant streams of Soto Zen in America: artistic, institutional, engaged, lay, monastic, scholarly, and creative.

Their contributions form the living tapestry of contemporary Zen, a dynamic unfolding of Dōgen’s ancient Way into the heart of modern life.

Sewing the Buddha’s Robe: Tomoe Katagiri, Angie Boissevain, Yuko Okumura, and Judy Putnam

In Soto Zen tradition, sewing the Buddha’s robe — whether a full okesa or a lay rakusu — is a profound ritual of devotion and mindfulness. The process is itself a practice of patience, humility, and gratitude, a literal stitching together of one’s aspiration to embody the Dharma.

As Zen took root in America, the art and practice of robe sewing were carefully preserved and transmitted by dedicated teachers, many of them women who wove together tradition and innovation with great care. Among them, Tomoe Katagiri, Angie Boissevain, Yuko Okumura, and Judy Putnam have played essential roles in nurturing this living lineage.

Tomoe Katagiri (b. 1935)

Tomoe Katagiri arrived in the United States with her husband, Dainin Katagiri, in the 1960s, first supporting his work at the San Francisco Zen Center and later co-founding the Minnesota Zen Meditation Center.

While Dainin Katagiri taught formal Zen practice, Tomoe quietly and powerfully transmitted the traditional arts of sewing, ritual, and daily life practice. She trained many students in the precise and heartfelt methods of sewing rakusu and okesa, preserving the forms passed down through Japanese Soto Zen monasteries.

Her teaching emphasized that sewing is not a craft but a practice of realization, mirroring the slow stitching of awakening itself — one stitch, one breath, one life.

Angie Boissevain (b. 1936)

Angie Boissevain, a dharma heir of Kobun Chino Otogawa, has become a prominent Zen teacher and sewing master in the American Soto tradition.

Ordained and receiving transmission in Kobun’s lineage, Boissevain leads Floating Zendo in San Jose, California. She is especially known for her sangha-centered approach to Zen, and for teaching rakusu and okesa sewing as a deep practice of humility, devotion, and attention.

In her instruction, Boissevain carries forward the spirit of Kobun’s warmth and creativity, inviting each student to find the thread of their own awakening in the quiet, deliberate act of sewing the Buddha’s robe.

Yuko Okumura (b. 1960s)

Yuko Okumura, sister of Shohaku Okumura, is a key figure in maintaining the ceremonial arts and sewing traditions at the Sanshin Zen Community in Bloomington, Indiana.

Working alongside her brother, Yuko has dedicated herself to preserving the precise forms of traditional Soto Zen robe sewing and supporting the practice life of the community. Through workshops, mentoring, and one-on-one guidance, she ensures that the transmission of sewing continues with care and fidelity.

Her gentle, steady presence embodies the spirit of service and quiet dedication that has always been the heart of Zen practice, reminding students that the robe is not merely cloth but the visible body of the Way.

Kaaren Wiken and Judith Putnam

Judith Putnam studied robe sewing closely under Kaaren Wiken, the senior student of Tomoe Katagiri. Wiken and Putnam have both continued to teach and support students in rakusu and okesa sewing, carrying forward the detailed techniques, traditional patterns, and devotional spirit they inherited.

Through patient instruction and encouragement, Wiken, Putnam, and others have helped generations of Western practitioners enter into the intimate, transformative practice of robe sewing — ensuring that this vital aspect of Soto Zen monastic and lay training remains vibrant in American practice communities.

Legacy

Through the dedicated work of Tomoe Katagiri, Angie Boissevain, Yuko Okumura, Kaaren Wiken, Judith Putnam, and others, the art and practice of sewing the Buddha’s robe have been carefully nurtured and transmitted in the West.

Each stitch embodies the vow to live the Buddha’s Way — a living thread connecting the earliest sanghas of India to the present moment.

In these simple acts of sewing, patience, and devotion, the timeless spirit of Zen continues to be woven anew.

The Symbolism of Sewing in Zen Practice

- Rakusu

A small rectangular robe worn around the neck, symbolizing the full Buddha robe (okesa). Traditionally sewn by hand by lay practitioners or monks upon ordination, jukai (lay vow ceremony), or priest ordination. - Okesa

The full monastic robe, worn draped over the left shoulder. The okesa represents the Buddha’s robe and is a direct symbol of renunciation, humility, and the vow to embody the Dharma. - Sewing Practice (Nuihō)

Sewing the rakusu or okesa is a formal Zen practice, emphasizing mindfulness, patience, and devotion. Each stitch embodies the practitioner’s vow to uphold the precepts and live according to the Buddha Way. - Sewing as Realization

In Soto Zen, sewing is not merely a practical task but a form of meditation itself — a realization of no-self and a physical expression of the inseparability of practice and enlightenment. - Transmission through Fabric

Just as Dharma is transmitted from teacher to student, so too the knowledge of sewing the Buddha’s robe is passed hand-to-hand, stitch-by-stitch, preserving the living tradition across generations.

Zen Scholars and Stewards of the Dharma: Leighton, Foulk, Bodiford, and Yifa

While Zen in the West has flourished through living communities of practice, it has also been enriched and sustained by careful scholarship. Translators, historians, and academic teachers have deepened understanding of Zen’s historical roots, doctrinal evolution, and cultural context — helping ensure that American Zen grows not only in spirit, but in wisdom.

Among the most influential scholar-practitioners are Taigen Dan Leighton, T. Griffith Foulk, William Bodiford, and Venerable Yifa — each contributing essential perspectives to the transmission of Zen’s living tradition.

Taigen Dan Leighton (b. 1950)

Taigen Dan Leighton is a Soto Zen priest, translator, and scholar known for his outstanding work in bringing Dōgen’s teachings to Western audiences. A dharma heir of Reb Anderson at the San Francisco Zen Center, Leighton has trained extensively in both Japan and the United States.

His translations and commentaries, particularly in collaboration with Shohaku Okumura, have made core Zen texts accessible to English readers — including Dōgen’s Extensive Record and Eihei Dōgen: Mystical Realist. In addition to his scholarship, Leighton has been deeply involved in engaged Buddhism and social justice, emphasizing that study and practice must inform one another.

Today, Leighton teaches through Ancient Dragon Zen Gate in Chicago, continuing to transmit both the spirit and the words of Soto Zen.

T. Griffith Foulk (b. 1950)

T. Griffith Foulk is one of the foremost Western scholars of Zen institutional history, known for clarifying the complex development of Zen schools in China and Japan. His research has been instrumental in dispelling myths about Zen’s origins, particularly the romanticized image of sudden, iconoclastic enlightenment.

Foulk’s translations and essays — such as “The Form and Function of Koan Literature” — have helped Western readers understand the ritual, educational, and sectarian realities behind the koan collections and Zen histories. He has also contributed to major collaborative works like The Zen Canon.

Through his scholarship, Foulk has illuminated the real historical evolution of Zen practice, balancing the inspiring ideals of the Zen tradition with careful academic precision.

William Bodiford (b. 1955)

William Bodiford is a Soto Zen priest and a professor at UCLA specializing in Japanese Buddhism, especially Soto Zen’s history and monastic practices. His landmark book, Sōtō Zen in Medieval Japan, is one of the definitive studies of how Dōgen’s tradition evolved after his death.

Bodiford has shown how Soto Zen became integrated into the Japanese countryside, blending formal practice with local customs, and how monastic codes such as Eihei Shingi shaped everyday life in Zen temples. His scholarship grounds Western Soto practitioners in a realistic understanding of their tradition’s roots — not as an unchanging ideal, but as a flexible, living organism responsive to time and place.

Through both academic teaching and temple work, Bodiford continues to build bridges between historical research and contemporary practice.

Venerable Yifa (b. 1959)

Venerable Yifa is a Taiwanese Buddhist nun, scholar, and translator whose work spans East Asian Buddhist studies, ethics, and human rights. Although more closely affiliated with Chinese Mahāyāna traditions, Venerable Yifa’s broad historical scholarship and interfaith work have greatly enriched understanding of Buddhism’s transmission across cultures, including Zen.

A graduate of Yale University’s Ph.D. program in Religious Studies, she has written on Buddhist precepts, monastic life, and Buddhist law. Her work encourages deeper reflection on the ethics and communal forms that underlie Zen practice, especially in a global, modern context.

Yifa’s projects also include major translation efforts, including work on the Fo Guang Buddhist Canon, making vast resources of Chinese Buddhist thought accessible to an international audience.

Honoring Sangha Leaders: Zuiko Redding (1949–2020)

A mention here must also be made of Zuiko Redding, a Soto Zen priest and founder of Cedar Rapids Zen Center in Iowa. A student of Daiji Tsugen Narasaki, Redding represented a bridge between Soto Zen scholarship and everyday practice, emphasizing careful study, deep sitting, and community service.

Her leadership, quiet strength, and simple practice have left a lasting impact on Zen communities across the American Midwest.

Legacy

Through the efforts of scholars and teachers like Taigen Dan Leighton, T. Griffith Foulk, William Bodiford, Venerable Yifa, and dedicated practitioners like Zuiko Redding, Zen in the West has become a tradition rooted not only in experience but in deep understanding.

Their work reminds us that Zen, while lived moment-to-moment, also carries a precious and intricate history — a living treasury that must be studied, appreciated, and passed on with care.

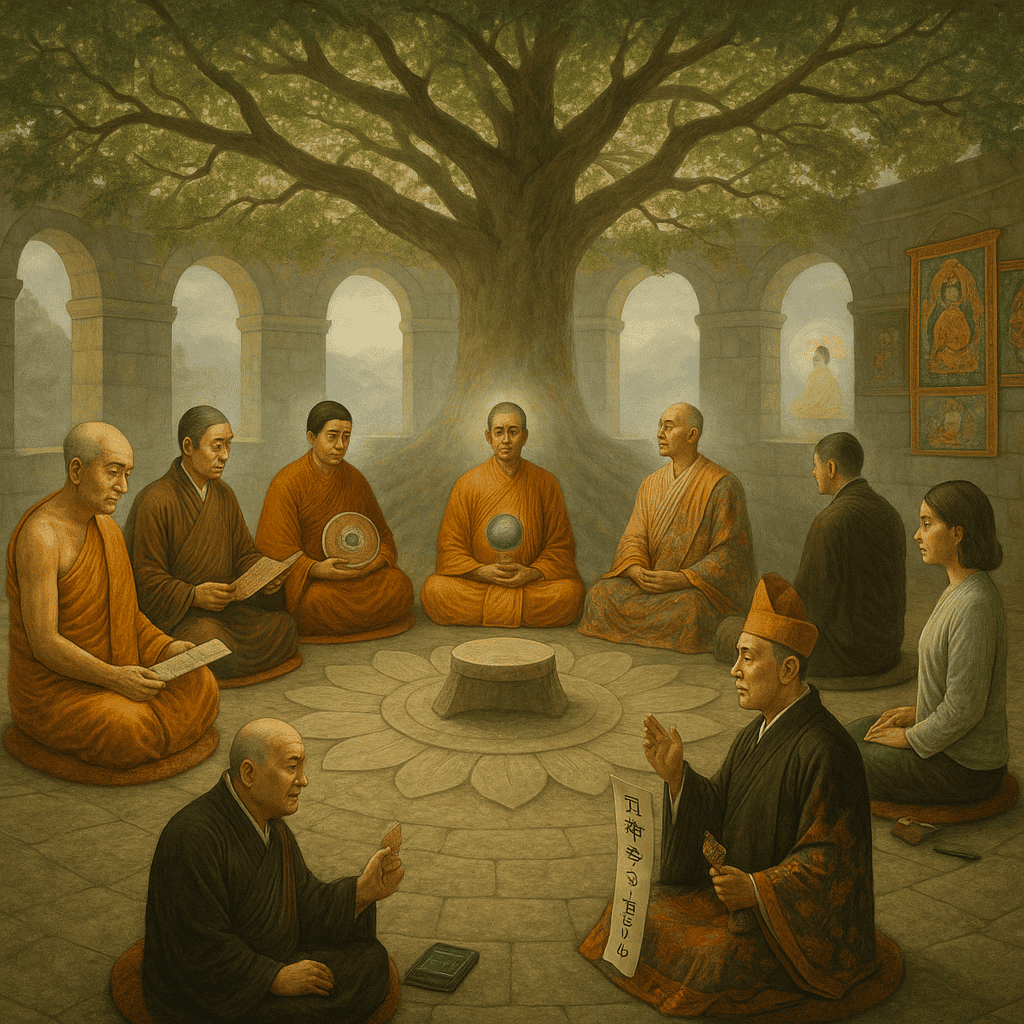

One Dharma: Soto Zen’s Relationship with Other Buddhist Traditions

While Soto Zen has developed a distinctive style of practice and community in the West, it has also maintained a spirit of openness and mutual respect toward other Buddhist traditions.

Throughout its history, Soto Zen has emphasized that beneath the many cultural forms, ritual expressions, and philosophical frameworks, there is ultimately one Buddha Way — the same transmission of wisdom and compassion flowing through all schools of Buddhism.

In contemporary practice, Soto Zen communities have forged warm and fruitful relationships with a wide range of Buddhist traditions — reaffirming that the true spirit of Buddhism transcends sectarian boundaries.

Chinese Chan: Dharma Drum Mountain

Soto Zen shares direct ancestry with Chinese Chan Buddhism, from which it originally emerged through Dōgen’s training under the Caodong (Sōtō) school in the thirteenth century.

In modern times, Soto Zen practitioners have engaged deeply with Chinese Chan teachers such as Master Sheng Yen (1930–2009), founder of Dharma Drum Mountain.

Master Sheng Yen emphasized a Chan practice of Silent Illumination (mozhao), which resonates profoundly with Soto Zen’s shikantaza.

Dialogue between Soto Zen and Dharma Drum communities has reaffirmed that stillness, clarity, and compassion are universal marks of true practice.

Korean Seon: Shared Roots of Meditation

Korean Seon Buddhism (from the same root as Chinese Chan) has also found natural affinity with Soto Zen.

Seon, which includes both hwadu (kōan-like questioning) and silent sitting, shares the Soto emphasis on meditative inquiry without attachment to concepts.

Many Soto Zen practitioners have engaged in respectful dialogue and collaboration with Korean Seon teachers, recognizing that Seon and Zen are siblings — sharing a profound commitment to direct, wordless realization.

Vietnamese Thiền: Thich Nhat Hanh

Perhaps the warmest and most influential relationship has been with the Thiền tradition of Vietnam, represented most famously by Thich Nhat Hanh (1926–2022).

A master of Zen, poet, and peace activist, Thich Nhat Hanh’s teachings on mindfulness, compassion, and interbeing have had a profound impact on Soto Zen practitioners worldwide.

His simple yet profound instructions on mindful breathing, walking, and living resonate closely with the Soto ideal of everyday practice. Soto Zen teachers and communities have often cited Thich Nhat Hanh’s work as a natural extension and complement to their own.

Tibetan Buddhism: Chögyam Trungpa and the Dalai Lama

Even across the traditional division between Zen and Tibetan Vajrayāna Buddhism, dialogue has flourished.

Figures like Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche (1939–1987) — founder of Shambhala and Naropa University — found common cause with Zen teachers in bringing direct meditative awareness into modern Western life.

The 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, has also expressed great respect for Zen practice, recognizing it as an authentic and vital branch of the Mahāyāna tradition.

In return, Soto Zen teachers have honored Tibetan Buddhism’s contributions to compassion, scholarship, and disciplined practice.

Thai Buddhism: Mindfulness and Simplicity

American Soto Zen practitioners have also found inspiration in Thai Theravāda Buddhism, particularly the Thai Forest Tradition.

The emphasis on mindfulness, simplicity, ethical living, and direct insight resonates with Soto values, even across historical and doctrinal differences.

Practitioners such as Ajahn Chah and Ajahn Sumedho have offered models of humble, practical, embodied Dharma that complement the Soto approach to zazen as awakening itself.

One Buddhism

Across these many expressions — Chan, Seon, Thiền, Vajrayāna, Theravāda — Soto Zen practitioners recognize a simple truth:

There are not many Buddhisms, but one Buddha Dharma, adapting itself across cultures and languages while remaining one unbroken reality.

At its heart, all Buddhist traditions teach:

- Ethical living (śīla)

- Concentration and meditation (samādhi)

- Wisdom and insight (prajñā)

Different methods, different metaphors — but the same liberation.

Soto Zen in America thus stands not as an isolated sect, but as a living participant in the great, unfolding body of the Buddha’s Way — walking together with all who seek to realize the truth of compassion, emptiness, and awakening.

Places of Stillness: American Zen Monasteries and Temples

As Zen Buddhism took root in the United States, practitioners sought not only to transmit the teachings and rituals of the tradition, but also to create spaces that embodied the spirit of Zen.

Across mountains, forests, prairies, and cities, American Zen temples and monasteries grew — shaped by traditional Japanese influences, yet deeply attuned to the landscape, climate, and culture of their new home.

These sacred spaces reflect the essence of Soto Zen: simplicity, harmony with nature, quiet dignity, and daily mindfulness.

Architectural Style: Simplicity and Integration

American Zen architecture preserves the core qualities of traditional Japanese Zen spaces:

- Minimalism — clean lines, natural materials, subdued colors.

- Environmental harmony — buildings nestled into forests, mountainsides, or farmland rather than dominating the landscape.

- Practicality — designs adapted to local climates and materials, rather than rigidly copying Japanese forms.

Though some centers include formal features like meditation gardens, gate arches, or pagoda-like structures, most American Zen monasteries and temples favor unpretentious, functional spaces that quietly invite practice.

The Zendo: Heart of Practice

The zendo (meditation hall) remains the central feature of all Zen monasteries and temples:

- Tatami mats, wooden floors, or simple platforms (tan) for seated meditation.

- Altars featuring a Buddha statue, candles, incense, and offerings.

- Symmetrical rows of cushions (zafu) and mats (zabuton), emphasizing equality and community.

Zendo architecture fosters an atmosphere of stillness and focus.

From formal monasteries like Zen Mountain Monastery (New York) to rural centers like Ryumonji Monastery (Iowa), the structure of the zendo embodies the seamless unity of practice and environment.

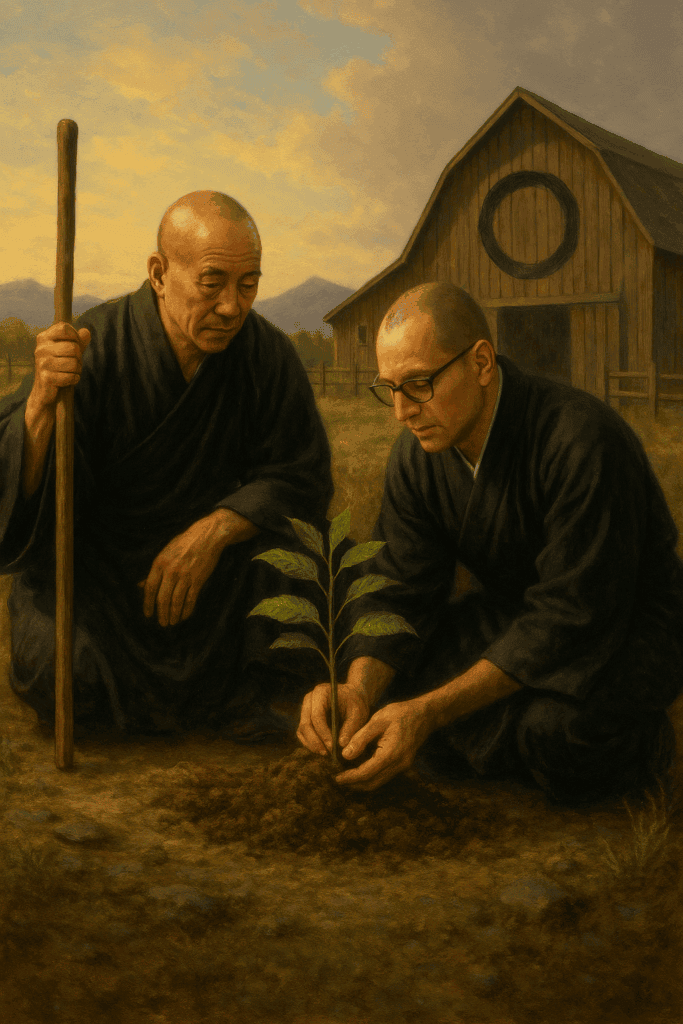

Ryumonji Zen Monastery: A Midwestern Expression

One of the most remarkable examples of American Zen monastic architecture is Ryumonji Zen Monastery, located in the rolling hills of Dorchester, Iowa.

Founded by Shōken Winecoff Roshi, a dharma heir in the lineage of Dainin Katagiri, Ryumonji represents a faithful yet creative expression of traditional Soto Zen monastic life in the American Midwest.

Built through years of community effort and devotion, Ryumonji features:

- A traditional zendo, with simple wood construction, natural light, and space for both seated meditation and ceremonies.

- Residential quarters for monastics and lay trainees, emphasizing communal living and daily practice.

- Gardens, forests, and open fields surrounding the monastery, reinforcing a sense of interconnection with the earth.

- Seasonal practice periods (ango) modeled on Japanese monastic training, yet adapted for the rhythms of American life.

Ryumonji exemplifies how Soto Zen practice can flourish in new environments, honoring tradition while growing organically from the American landscape.

Temple Interiors: Ritual and Daily Life

Inside American Zen temples and monasteries, the interiors are designed to support both formal practice and daily community life:

- Altars for offering incense, flowers, and food to the Buddha and the ancestors.

- Dharma halls or teaching rooms for lectures, discussion, and ceremonies.

- Dining halls (jikidō) where silent meals or oryoki practice meals are held.

- Residential spaces designed for simplicity, shared responsibility, and mindful living.

Furniture remains minimal:

- Low wooden altars, bell stands, offering tables, and floor cushions predominate.

- Screens and sliding doors sometimes separate spaces without fully enclosing them, maintaining an open flow.

- Where needed, American adaptations (such as accessibility features, climate insulation, or radiant heating) are incorporated with care.

Spirit of Place

Whether in the mountain wilderness of Tassajara, the forests of upstate New York, the prairies of Iowa, or suburban temples nestled among neighborhoods, American Zen architecture expresses a profound truth:

Zen practice is not limited to Japan, nor to any one style — it grows wherever sincerity, stillness, and mindfulness take root.

Each temple, zendo, and monastery becomes a field of practice, cultivating the seeds of awakening through the ordinary acts of sitting, bowing, working, cooking, sewing, and living together.

Legacy

The physical spaces of American Zen — from simple zendos in converted houses to full monastic complexes like Ryumonji — are not merely buildings.

They are living vessels of the Buddha’s teaching, expressions of silence made visible, spaces where the mind may settle, the heart may open, and the Dharma may be encountered without words.

Through simplicity, harmony, and careful attention, these sacred spaces continue to nourish the unfolding of Zen in the Western world.

A Day in the Life of an American Soto Zen Priest

In Soto Zen Buddhism, priesthood is not a clerical profession in the Western sense, but a life of vow and practice.

A Soto Zen priest lives not to preach doctrines, but to embody the Buddha Way in everyday actions — in meditation, in ritual, in community service, and in silent presence.

Whether in a monastery, temple, urban zendo, or rural retreat, the daily life of an American Soto Zen priest is grounded in the same rhythms of mindfulness, humility, and service that have guided monastics for centuries.

Daily Schedule

Though variations exist depending on the temple or sangha, a typical day in the life of a Soto Zen priest includes:

- 4:30–5:00 AM: Wake Up

Early rising symbolizes the commitment to living each day fully awake. Silence and mindfulness are practiced from the first moments of the day. - 5:00–6:30 AM: Morning Zazen and Service

Priests and lay practitioners sit zazen (seated meditation), often followed by chanting services dedicating merit to the Buddha, ancestors, and all beings. - 7:00 AM: Breakfast

At monasteries, this may involve oryoki — a formal, silent, ritualized meal. In urban centers, breakfast is often simpler but still mindful. - 8:00 AM–12:00 PM: Work Practice (Samu)

Cleaning, gardening, cooking, administration, teaching — all work is done with full attention, blurring the distinction between “practice” and “life.” - 12:00 PM: Lunch

Another opportunity for oryoki or mindful communal eating. - 1:00–4:00 PM: Study, Teaching, or Administration

Priests engage in scriptural study, translation work, preparing talks (teisho), counseling sangha members, or managing temple affairs. - 4:00–5:00 PM: Afternoon Zazen

Another period of meditation to settle the mind amidst daily busyness. - 5:30 PM: Dinner

Often a light, informal meal. - 7:00–8:30 PM: Evening Practice

Evening zazen, service, chanting, or Dharma study with the community. - 9:00 PM: Lights Out

Rest is itself a practice — a preparation for another day of vow and mindfulness.

The Path of Priesthood: Ordination and Progression

Becoming a Soto Zen priest involves lifelong training and progression through traditional stages, blending personal commitment, ritual recognition, and deep practice realization.

1. Lay Ordination (Zaike Tokudo)

Many practitioners begin with lay ordination — taking the Sixteen Bodhisattva Precepts in a jukai ceremony.

Receiving a rakusu (small Buddha robe) and a Buddhist name, lay practitioners formally enter the Buddhist path, committing to ethical living and mindfulness within everyday life.

2. Priest Ordination (Shukke Tokudo)

Those called to full religious life receive shukke tokudo — “leaving home and ordaining.”

In this ceremony, the aspirant:

- Shaves their head (symbol of renunciation).

- Receives priest’s robes (okesa).

- Takes the Bodhisattva Precepts again, this time with the intention of lifelong service to the sangha and the Buddha Way.

The new priest is considered a novice (unsui, “clouds and water”), and enters a period of intensive training under the guidance of a teacher.

3. Novice Priest Training (Unsui Period)

In this stage, the priest-in-training:

- Lives in a monastery or practice center, engaging in daily zazen, chanting, work practice, and ceremonies.

- Learns liturgy, ritual forms, administrative responsibilities, and teaching skills.

- Continues formal study of Buddhist texts, Dōgen’s writings, and Zen history.

- Serves the sangha through acts of daily support, humility, and devotion.

This period may last for several years, often culminating in priest ordination ceremonies or reaffirmations.

4. Full Priest Recognition (Denkai and Dharma Entrustment)

Through mutual recognition between teacher and student, a novice may receive Denkai — transmission of the precepts — symbolizing the internalization of ethical conduct.

In time, the teacher may offer Dharma Entrustment (Shihō), formally recognizing the student as an independent priest authorized to teach and guide others.

This transmission reflects not only ritual readiness but the maturing of character, compassion, and insight.

5. Dharma Transmission (Shiho) and Dharma Heir (Denbo)

Shiho — dharma transmission — is the formal acknowledgment that the priest has fully received the lineage teachings.

They become a Dharma Heir (denbo-sha), carrying the living transmission of their teacher and the Soto lineage back to Shakyamuni Buddha.

Dharma transmission includes:

- Receiving formal documents.

- Authorization to ordain others and teach independently.

- An obligation to protect and nurture the sangha, not for personal fame, but as an act of gratitude and service.

6. Inka Shomei (Seal of Certification)

Rare among Soto priests but sometimes conferred, Inka Shomei (“Seal of Approval”) is an additional certification recognizing deep realization and mature leadership.

Inka is typically reserved for those who have demonstrated unwavering devotion, realization, and leadership over many years.

It symbolizes responsibility to uphold the tradition with integrity, wisdom, and compassion — and often accompanies responsibilities such as abbacy or training master roles.

A Life of Vow

To be a Soto Zen priest is to live a life woven with silence, service, ritual, and humility — where every breath, every bow, every step expresses the vow to liberate all beings.

It is not a career or a social title, but a continuous act of devotion, a daily sewing together of practice and realization in the fabric of ordinary life.

In America, Soto Zen priests strive to uphold the ancient forms while adapting to the needs of modern sanghas, embodying the timeless truth that Buddhahood is found not elsewhere, but here and now, in the midst of everyday life.

Challenges and Adaptations: Zen in American Culture

The transplantation of Soto Zen to American soil has been a profound success — a flowering of practice, understanding, and community across diverse regions and generations.

Yet like any living tradition, American Zen has faced real challenges and growing pains as it adapts to a new cultural, social, and historical environment.

Rather than undermining the tradition, these challenges have often catalyzed self-reflection, reform, and maturation, helping American Zen evolve toward a more grounded, inclusive, and ethical expression of the Buddha Way.

Teacher Scandals and the Evolution of Ethical Standards

One of the most painful challenges in the history of American Zen has been the occurrence of teacher scandals — involving issues of sexual misconduct, financial impropriety, and abuses of power.

Early pioneers, including charismatic Japanese and Western teachers, often operated without clear oversight, formal ethics guidelines, or cultural awareness of the expectations and protections necessary in American religious communities.

Scandals in several prominent centers shook faith in institutional Zen and forced sanghas to confront questions of authority, accountability, and ethics.

In response, most major Zen organizations in America have since adopted:

- Clear ethical guidelines for teachers and students.

- Grievance procedures for addressing misconduct.

- Shared leadership models to prevent unchecked authority.

- Ongoing ethics training for ordained priests and lay leaders.

These reforms reflect a maturing of the sangha — a recognition that spiritual depth must be matched by ethical transparency and integrity.

The Lay-Monastic Balance

Another challenge has been navigating the lay-monastic divide in a culture where lifelong monasticism is rare.

Unlike in Japan, where a priestly caste often runs temples while married with families, and where centuries-old traditions support monastic life, American Zen communities needed to develop new models suited to a predominantly lay society.

Today, American Soto Zen includes:

- Full monastic training centers (e.g., Tassajara, Zen Mountain Monastery).

- Lay-based urban centers (e.g., Berkeley Zen Center, Everyday Zen Foundation).

- Hybrid models, where priests live “in the world” but maintain deep commitment to practice.

This flexibility has allowed Zen practice to thrive among householders, working professionals, and retirees, without losing the heart of zazen, ethical conduct, and compassionate action.

At the same time, maintaining serious training opportunities for those called to priesthood remains an ongoing priority — ensuring that the depth of Zen is preserved even as its forms adapt.

Psychotherapy and the Mindfulness Movement

The integration of Zen principles into Western psychotherapy has been both a tremendous strength and a subtle challenge.

On one hand, the insights of Zen — into mindfulness, emotional regulation, and the nature of the self — have enriched clinical psychology, giving rise to practices such as:

- Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR).

- Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT).

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT).

Teachers like Jon Kabat-Zinn and others have drawn explicitly on Zen principles to help millions cope with suffering.

However, there is an ongoing tension:

- Mindfulness practices, when separated from the ethical and philosophical roots of Buddhism, risk becoming commodified, diluted, or superficial.

- True Zen practice is not merely stress reduction but a profound encounter with impermanence, non-self, and the vow to liberate all beings.

Many Soto Zen teachers continue to engage with the broader mindfulness movement, while also reminding practitioners that mindfulness is a doorway, not the goal — a practice inseparable from compassion, ethics, and deep realization.

Tradition and Innovation: The Tension of Growth

As American Zen has evolved, it has also wrestled with the balance between preserving traditional forms and adapting to contemporary needs.

Tensions include:

- Ritual forms: How much Japanese liturgy, chanting, and ceremonial precision should be maintained? When should English adaptations or new rituals be created?

- Leadership roles: How can women, BIPOC, LGBTQ+, and younger practitioners find authentic expression and leadership within a tradition historically bound to hierarchical, male-dominated structures?

- Social engagement: How can Zen remain committed to inner transformation while addressing urgent social and ecological issues?

The answers vary across sanghas, reflecting a dynamic, decentralized, and pluralistic approach.

Rather than seeing these tensions as signs of decline, many practitioners view them as the natural process of a living Dharma — testing, refining, and expressing the timeless truths of Buddhism in a new world.

A Living Dharma

American Soto Zen today is not a perfect replica of Japanese monastic life — nor should it be.

It is a living, breathing practice: rooted in the profound stillness of zazen, tested by cultural challenges, and adapted with courage, humility, and creativity.

The heart of Soto Zen — the direct realization of the Buddha Way through everyday life — continues to shine through:

in zendos and monasteries, in homes and workplaces, in the quiet determination of those who sit, who bow, who serve, and who vow to wake up for the sake of all beings.

Through every challenge and every adaptation, the thread of the Dharma remains unbroken.

Conclusion: The Great Bright Pearl

Long ago, under the cool shade of a bodhi tree, Siddhartha Gautama sat down and vowed not to rise until he had realized the truth of this life.

Through fierce dedication and deep stillness, he awakened — not to another world, but to the vivid, luminous reality of this very one: impermanent, empty, interdependent, and shining beyond all comprehension.

Centuries later, in a distant foreign land, a wandering monk named Bodhidharma carried this same realization across the mountains and rivers of China.

There he spoke of “directly pointing to the mind” — a teaching without reliance on words or letters, transmitted heart to heart.

From this transmission arose the river of Chan, where in time Dongshan Liangjie taught of the “Great Bright Pearl” — the image of existence itself, shining with undivided brilliance, each moment complete, each being inseparable from awakening.

In thirteenth-century Japan, a young seeker named Eihei Dōgen brought this vision even further, after crossing stormy seas to study with the heirs of Dongshan’s school.

He returned not merely with words, but with the living marrow of the Way: that practice and realization are one, and that to sit down in stillness is to immediately, fully express the Buddha’s enlightenment.

After Dōgen’s death, his disciple Keizan Jōkin spread the Dharma into the countryside, into the lives of ordinary farmers and townspeople — ensuring that the Great Bright Pearl was not locked away in monasteries, but could shine in every kitchen, every rice field, every breath.

And now, in the twenty-first century, on distant shores Dōgen never knew, in valleys, mountains, cities, and small towns across America, the Great Bright Pearl continues to shine.

It shines in zendos where seekers sit silently through the long hours of dawn.

It shines in lay teachers and householders balancing families and zazen.

It shines in gardens and kitchens, in sewing rakusus, in chanting services, in the hard work of ethical reform, social engagement, and cultural adaptation.

This Zen, now American, is not a replica, but a living descendant — shaped by vast migrations, painful reckonings, fierce devotion, and boundless creativity.

The vow made by Siddhartha under the bodhi tree lives on — stitched into robes, bowed into altars, breathed into the silence of early mornings.

There is no East or West in the Great Bright Pearl.

There is only practice.

There is only realization.

There is only this wondrous, luminous, impermanent life — yours, mine, and all beings’, shining without end.

Gasshō.

Epilogue: Carrying the Bright Pearl Forward

The Great Bright Pearl is not hidden in distant monasteries or lost to ancient time.

It is here, in the breath you are breathing, in the ground beneath your feet, in the rising and falling of your own heart.

You do not need to cross oceans, climb mountains, or master ceremonies to find it.

You need only sit down, be still, and listen.

The lineage of Siddhartha, Bodhidharma, Dongshan, Dōgen, and Keizan lives not in statues or scrolls, but in the living practice of ordinary people who vow — again and again — to meet this very life with patience, compassion, and unwavering attention.

Whether in a monastery, a temple, a home, a city, or a quiet room, the invitation remains the same:

Sit. Breathe. Bow. Awaken. Serve.

Each step forward is a continuation of the Way.

Each act of mindfulness, each kindness offered to another, is another stitch in the endless robe of awakening.

The Great Bright Pearl is already shining.

It waits only for you to realize it, and to carry its light forward

— for the benefit of all beings.

Author’s Note

This work is offered in gratitude to the endless stream of teachers, practitioners, scholars, and unseen laborers who have preserved and transmitted the Buddha Way across continents, centuries, and cultures.

It is dedicated especially to those who sit in quiet zendos, bow in hidden temples, and walk mindfully through everyday life — carrying the light of the Great Bright Pearl in their hands, their hearts, and their breath.

May these words serve as a lantern, however small, along the vast and boundless path of practice.

Gasshō.

Inside Monastic Culture Series

Virgins and Philosophers: Early Proto-Monasticism

From Hermits to Orders: The Solitary Roots of Monastic Culture

The First Monks Rise in the East: The Birth of Monasticism

Christian Monasticism, University, and Lectio Divina Meditation

Monks of War: The Military Orders

The Confucian Monastic Tradition

The Evolution of Japanese Monastic Life

Soto Zen from India to America

AUTHOR

D. B. Smith is an independent historian, ritualist, and comparative religion scholar specializing in the intersections of Western esotericism, Freemasonry, and Eastern contemplative traditions. He formerly served as Librarian and Curator at the George Washington Masonic National Memorial, overseeing historically significant artifacts and manuscripts, including those connected to George Washington’s personal life.

Initiated into The Lodge of the Nine Muses No. 1776, a philosophically focused lodge in Washington, D.C., Smith studied under influential figures in the Anglo-American Masonic tradition. His work has been featured in national and international Masonic publications, and his efforts have helped inform exhibits, lectures, and a televised documentary on the history and symbolism of Freemasonry.

Smith’s parallel study and practice of Soto Zen Buddhism—including ordination as a lay practitioner in the Katagiri-Winecoff lineage—has led him to investigate convergences between ritual, mindfulness, symbolic systems, and the evolving role of spiritual practice in secular societies. He is the founder of Science Abbey, a platform for interdisciplinary inquiry across religion, philosophy, science, and cultural history.