Table of Contents

- The Mountain Path: Sōtō Zen and Its Living Tradition

- Sōtō Zen Monasticism: Origins and Foundations

- Eihei Dōgen: Early Life and Formation

- Dōgen’s Return to Japan and Early Teachings

- The Founding of Eihei-ji and Dōgen’s Final Years

- Early Sōtō Zen Monasticism After Dōgen

- Keizan Jōkin and the Expansion of Sōtō Zen

- The Structure and Daily Life of Early Sōtō Zen Monasteries

- The Sōtō School During the Muromachi Period

- Sōtō Zen in the Edo Period

- Sōtō Zen in the Meiji Period and Modern Era

- Koan and Shikantaza

- Origins of Shikantaza

- Interpreting Shikantaza

- Conclusion: The Living Tradition of Sōtō Zen

The Mountain Path: Sōtō Zen and Its Living Tradition

In the stillness before dawn, when the world lies silent and unseen, there is a place where monks sit facing a blank wall, seeking nothing, grasping nothing, becoming one with the breath of existence. This is the heart of Sōtō Zen — a tradition that has journeyed across centuries and oceans, carrying the quiet lamp of awakening through times of upheaval, simplicity, and change.

Sōtō Zen was born from a deep current of wisdom that flows from India through China to Japan, shaped not by conquest or proclamation, but by the gentle, steadfast practice of sitting in silence. It is a path where the ordinary becomes sacred, where each step, each meal, each breath is itself the unfolding of the Buddha Way.

In the mountains of Echizen, where Eihei Dōgen founded Eihei-ji, and in countless villages and cities thereafter, Sōtō Zen took root — not through spectacle, but through the cultivation of everyday awareness and the humble transmission of teachings from teacher to student, heart to heart.

This article traces the life of Sōtō Zen from its beginnings in medieval Japan to its flourishing in the modern world, following the enduring spirit of those who found enlightenment not in grand visions, but in the deep stillness of things as they are.

Sōtō Zen Monasticism: Origins and Foundations

Zen Buddhism entered Japan after a long process of transmission and development across Asia. Originating in India, Buddhist teachings spread through Central Asia to China, where they were adapted and refined into the school of meditation known as Chan.

Chan Buddhism later traveled to Korea, where it became Soen, and eventually reached Japan, where it was known as Zen. Among the three traditional schools of Zen in Japan—Rinzai, Sōtō, and Ōbaku—the Sōtō school (曹洞宗, Sōtō-shū) would become the largest and most widely practiced.

Sōtō Zen traces its roots to the Chinese Cáodòng lineage, developed during the Tang dynasty by the Chan masters Dongshan Liangjie (807–869) and Caoshan Benji (840–901). The name of the school itself derives from the first characters of their names. The Cáodòng tradition emphasized silent meditation (mo zhao chan) and the direct realization of the unity of practice and enlightenment.

Buddhism first entered Japan from Korea in the sixth century and became firmly established under imperial patronage during the Nara and Heian periods. Early Japanese Buddhism was dominated by esoteric and scholastic traditions such as Tendai and Shingon. Zen, with its emphasis on meditation over ritual and scripture, did not take root in Japan until the late twelfth century, during a period of political and cultural transition.

Among the earliest promoters of Zen practice was Myōan Eisai (1141–1215). Originally ordained in the Tendai school, Eisai traveled to China, where he studied in the Linji lineage of Chan. Returning to Japan in 1191, he founded Hōon-ji in Kyushu, and later Kennin-ji in Kyoto in 1202, considered Japan’s first Zen temple. Eisai introduced not only Zen teachings but also tea culture, bringing tea seeds from China and promoting the health and spiritual benefits of tea drinking.

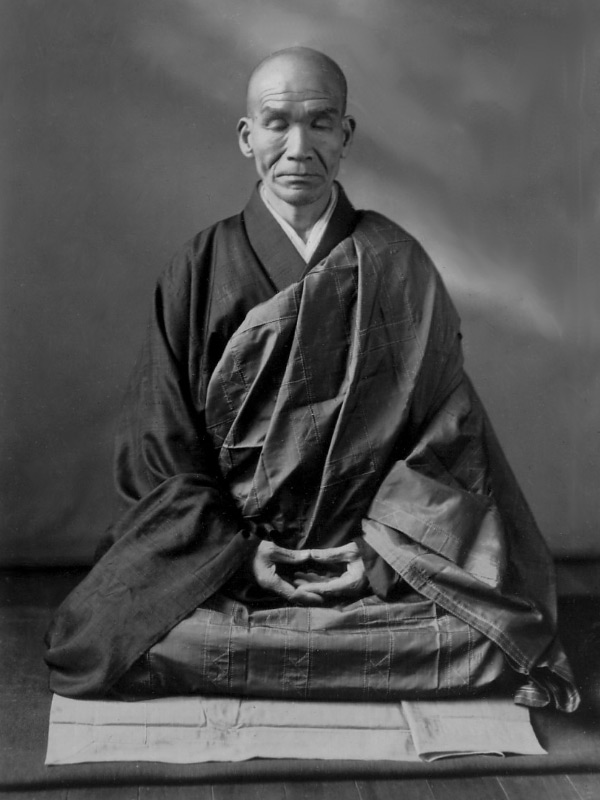

Following in Eisai’s footsteps, Eihei Dōgen (1200–1253) sought a deeper understanding of Buddhist practice. Ordained as a Tendai monk, Dōgen traveled to China in 1223 and studied at several Chan monasteries. He eventually received Dharma transmission from Tiantong Rujing (1163–1228), abbot of Tiantong Monastery and a master of the Cáodòng lineage. Dōgen returned to Japan with a strong conviction in the primacy of zazen, or seated meditation, as the heart of Buddhist practice.

Dōgen initially taught at Kennin-ji but later withdrew from Kyoto to establish a monastic community in the remote mountains of Echizen Province. In 1244, he founded Eihei-ji, a training monastery dedicated to the practice of zazen and strict monastic discipline.

Dōgen composed several foundational texts, including the Fukanzazengi (Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen), which introduced zazen to Japanese practitioners, and the Eihei Shingi (Pure Standards for the Zen Community), a monastic code inspired by earlier Chinese regulations such as the Chanyuan Qinggui.

The consolidation and expansion of the Sōtō school were later carried forward by Keizan Jōkin (1268–1325), often referred to as the second founder of Sōtō Zen. Keizan, whose family had deep connections to Dōgen’s lineage, trained at Eihei-ji from an early age. He worked to broaden the reach of Sōtō Zen beyond the cloistered monastic setting, founding temples such as Yōkō-ji and Sōji-ji, and making the teachings accessible to lay communities.

Through the efforts of Dōgen and Keizan, Sōtō Zen established itself as a major tradition within Japanese Buddhism. Its monasteries emphasized simplicity, meditation, and communal living, preserving the spirit of the original Chan teachings while adapting to the religious and social landscape of medieval Japan. Over the centuries, Sōtō Zen developed a distinctive monastic culture that continues to thrive in Japan and around the world today.

Eihei Dōgen: Early Life and Formation

Eihei Dōgen (1200–1253) was born into a distinguished family during the late Heian period, a time of political decline and social unrest. His father was believed to have been a high-ranking government official, possibly connected to the powerful Fujiwara clan, and his mother is remembered for her deep religious devotion.

Despite his aristocratic background, Dōgen’s early life was marked by profound personal loss. By the time he was eight years old, both of his parents had passed away. This early experience of impermanence left a deep and lasting impression on him, shaping his later religious outlook.

At the age of thirteen, Dōgen entered monastic life at Enryaku-ji, the headquarters of the Tendai school, located on Mount Hiei near Kyoto. Enryaku-ji was at that time the foremost Buddhist institution in Japan, preserving a rich but increasingly complex and scholastic tradition.

As a novice, Dōgen received a classical Buddhist education, studying sutras, doctrinal commentaries, and the intricate teachings of the Tendai school. However, he soon grew troubled by a fundamental question: if all beings are inherently endowed with Buddha-nature, why must one engage in arduous practices to attain enlightenment?

This question remained unresolved during his early years of training. Although he continued his studies with earnest dedication, Dōgen became increasingly dissatisfied with the doctrinal debates and the political entanglements of the Tendai establishment.

Seeking a more direct and authentic expression of the Buddha’s teachings, he left Mount Hiei and entered the smaller Tendai-affiliated temple of Kennin-ji in Kyoto, founded by Myōan Eisai. Kennin-ji maintained a closer connection to Chinese Chan practice and offered a new model of Zen training that emphasized meditation.

Under the guidance of the monk Myōzen (1184–1225), a senior disciple of Eisai, Dōgen deepened his practice of zazen and prepared for a journey of further spiritual seeking. In 1223, at the age of twenty-three, he accompanied Myōzen and a group of monks on a perilous voyage across the sea to Song Dynasty China. Their aim was to visit the great monasteries and teachers of Chan Buddhism, where Dōgen hoped to find answers that had eluded him in Japan.

During his two years in China, Dōgen visited several major monasteries but remained cautious of schools that appeared overly focused on ritual or intellectual study. His decisive encounter came at Tiantong Monastery, where he trained under the strict discipline of the Caodong master Tiantong Rujing. Under Rujing’s firm guidance, Dōgen experienced a profound spiritual awakening, a realization of the unity of practice and enlightenment through the simple act of seated meditation.

Having received Dharma transmission from Rujing, Dōgen returned to Japan in 1227 at the age of twenty-seven. He brought with him not only the formal seal of a lineage but also a clear vision of the path he would dedicate his life to: the wholehearted practice of zazen, free from sectarian entanglements and worldly ambition.

His first major act on returning was the composition of the Fukanzazengi, a concise and universal set of instructions for meditation practice, marking the beginning of his life’s work to establish an independent Zen tradition in Japan.

Dōgen’s Return to Japan and Early Teachings

Upon his return to Japan in 1227, Eihei Dōgen did not seek to establish a new sect or gather a large following. Instead, he focused on transmitting the essence of what he had realized in China: the practice of zazen as the full embodiment of the Buddha’s teaching.

Initially, he resumed residence at Kennin-ji in Kyoto, where he quietly taught a small group of students and composed the Fukanzazengi (“Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen”), his first written work. In this concise treatise, Dōgen emphasized that zazen is not a means to an end but the direct manifestation of enlightenment itself.

At Kennin-ji, Dōgen’s approach to Zen soon distinguished itself from the prevailing styles of Buddhist practice in Kyoto. While other teachers sought imperial patronage or participated in sectarian competition, Dōgen advocated for a return to the simplicity of seated meditation, free from elaborate rituals or public displays. His teachings were initially met with limited support, and the political and religious tensions of Kyoto made it difficult for him to establish a stable monastic community.

In 1230, Dōgen moved to a small temple called An’yō-in, located on the outskirts of Kyoto. There he continued to attract a modest number of dedicated disciples, among them Koun Ejō (1198–1280), who would later become his chief successor.

During this period, Dōgen began to expand his teaching activities and composed several important works, including the early fascicles of the Shōbōgenzō (“Treasury of the True Dharma Eye”), a collection of sermons and essays that would become the cornerstone of Sōtō Zen thought.

Dōgen’s teachings during these years emphasized the unity of practice and enlightenment (修証一等, shushō ittō) and the idea that daily actions — eating, working, sitting, and even sleeping — could become full expressions of the awakened mind if approached with mindful attention. He criticized reliance on ritual merit-making, scholastic debates, and institutional power, urging practitioners instead to enter directly into the Way through wholehearted practice.

By 1233, Dōgen established a more permanent center for his community by founding the Kōshōhōrin-ji temple in Fukakusa, just south of Kyoto. This small monastery offered a space dedicated entirely to zazen and monastic discipline, in contrast to the larger temples still shaped by Heian-period religious culture.

At Kōshōhōrin-ji, Dōgen formally organized the first training monastery for Sōtō Zen in Japan, setting in motion a new model of Buddhist practice focused on rigorous training, simplicity, and self-cultivation.

Despite these successes, Dōgen remained wary of the growing political pressures and the entanglement of religion with secular authority in the capital. Seeking to protect the integrity of his teaching and to provide a setting more suited to intensive training, he would soon make a decisive move — leaving the Kyoto region entirely to establish a monastery in the remote mountains of Echizen Province, where his vision of Zen monasticism could be realized without compromise.

The Founding of Eihei-ji and Dōgen’s Final Years

In 1243, seeking a location where monastic training could be pursued without interference from the secular and religious authorities of Kyoto, Dōgen accepted an invitation from a lay supporter, the samurai lord Hatano Yoshishige. With Hatano’s assistance, Dōgen and his small community relocated to Echizen Province, in the remote mountains of present-day Fukui Prefecture.

There, in the forests of the Gifu region, Dōgen established a new monastery originally called Daibutsu-ji (“Great Buddha Temple”), soon renamed Eihei-ji (“Temple of Eternal Peace”). The founding of Eihei-ji marked the realization of Dōgen’s vision: a secluded, self-sufficient monastic community where the practice of zazen, monastic discipline, and everyday activity were all integrated into the life of the sangha.

At Eihei-ji, Dōgen composed some of his most important writings, including the later fascicles of the Shōbōgenzō and the Eihei Shingi (“Pure Standards for the Zen Community”), a set of regulations that outlined the daily conduct of monastics, inspired by earlier Chinese Chan monastic codes but adapted to the Japanese context. These writings emphasized not only meditation but also the manner in which meals were taken, robes were worn, and work was carried out — every action seen as an opportunity for awakening.

Dōgen’s teaching at Eihei-ji was marked by an insistence on sincerity and diligence. He rejected the idea that enlightenment could be obtained through special experiences or secret teachings, affirming instead that practice itself was enlightenment. In his view, the true Way could only be realized by thoroughly embodying it moment by moment, without striving for attainment.

Although Eihei-ji remained relatively small during Dōgen’s lifetime, it laid the foundation for the future spread of Sōtō Zen across Japan. His community at Eihei-ji maintained a strict schedule of zazen, chanting, ritual observances, and manual labor, creating a model of monastic life that would endure for centuries.

In 1252, after nearly a decade of leading the community at Eihei-ji, Dōgen’s health began to decline. He entrusted the care of the monastery to his disciple Koun Ejō and traveled to Kyoto to seek medical treatment. There, at the residence of a lay supporter, Dōgen continued to teach until the end of his life.

Eihei Dōgen passed away on the 28th day of the 8th month of 1253, at the age of fifty-three. His final instructions to his disciples emphasized the importance of preserving the spirit of sincere practice. Though his death passed quietly, without the recognition afforded to more prominent religious figures of his time, Dōgen’s legacy would steadily grow through the efforts of his successors.

Today, Eihei-ji remains one of the two principal temples of the Sōtō Zen school, alongside Sōji-ji, founded later by Keizan Jōkin. Dōgen’s teachings, particularly as preserved in the Shōbōgenzō, continue to be regarded as among the most profound expressions of Zen thought, embodying a vision of Buddhist practice grounded in simplicity, mindfulness, and the unity of practice and awakening.

Timeline of Eihei Dōgen (1200–1253)

- 1200 – Birth of Dōgen into an aristocratic family in Kyoto.

- c. 1208 – Orphaned at a young age; early encounter with the Buddhist teaching of impermanence.

- 1213 – Ordained as a novice monk at Enryaku-ji, headquarters of the Tendai school.

- 1217–1223 – Studies at Kennin-ji under Myōzen, deepening his meditation practice.

- 1223 – Travels to China with Myōzen; visits major Chan monasteries.

- 1225 – Trains under Tiantong Rujing at Tiantong Monastery; receives Dharma transmission.

- 1227 – Returns to Japan; composes the Fukanzazengi and teaches at Kennin-ji.

- 1230 – Moves to An’yō-in temple to establish a smaller, independent community.

- 1233 – Founds Kōshōhōrin-ji in Fukakusa, south of Kyoto; begins formal Sōtō monastic training.

- 1243 – Relocates to Echizen Province with disciples; prepares to establish a new monastery.

- 1244 – Founds Eihei-ji, “Temple of Eternal Peace,” in the mountains of Echizen.

- 1252 – Health declines; entrusts Eihei-ji’s leadership to Koun Ejō.

- 1253 – Death of Dōgen in Kyoto at the age of fifty-three.

Major Works of Eihei Dōgen

- Fukanzazengi (普勧坐禅儀)

“Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen” (1227)

A concise guide to the practice of seated meditation (zazen), emphasizing that zazen itself is the complete expression of enlightenment. - Shōbōgenzō (正法眼蔵)

“Treasury of the True Dharma Eye” (written 1231–1253)

A collection of essays and sermons exploring the nature of practice, realization, time, language, and the Buddha’s teaching, considered Dōgen’s central philosophical work. - Eihei Shingi (永平清規)

“Pure Standards for the Zen Community” (1249)

A set of monastic regulations outlining daily life, conduct, rituals, and communal practices at Eihei-ji, based on Chinese Chan precedents but adapted for Japan. - Bendōwa (弁道話)

“A Talk on Wholehearted Practice of the Way” (1231)

A dialogue-format treatise elaborating on the importance of zazen and addressing common questions about Zen practice. - Tenzo Kyōkun (典座教訓)

“Instructions for the Cook” (1237)

A manual for the monastery cook (tenzo), emphasizing mindfulness and devotion in even the most ordinary tasks, reflecting Dōgen’s teaching that practice permeates all activities.

Main Disciples of Eihei Dōgen

- Koun Ejō (1200–1280)

Dōgen’s chief disciple and successor at Eihei-ji; editor of Dōgen’s recorded sayings and the second abbot of Eihei-ji. - Tettsū Gikai (1219–1309)

A senior disciple who later served as abbot of Eihei-ji; instrumental in transmitting Sōtō Zen practices to wider regions. - Jakuen (c. 1207–c. 1299)

A Chinese monk and close attendant of Dōgen; later founded Hōkyō-ji, preserving Dōgen’s strict style of monastic training. - Kangan Giin (1217–1300)

Disciple who helped establish Sōtō Zen temples in Kyushu; emphasized Dōgen’s teachings in new regions. - Gien (dates unknown)

Disciple active in supporting the early spread of Sōtō Zen and maintaining Dōgen’s lineage during times of transition.

Following Dōgen’s death in 1253, leadership of Eihei-ji passed to his senior disciple Koun Ejō. Under Ejō’s careful stewardship, Dōgen’s vision of rigorous meditation-centered monastic life was preserved and gradually expanded. Although the early Sōtō community remained small and faced internal challenges, the foundations laid by Dōgen would endure.

Over the following generations, through the efforts of Ejō, Tettsū Gikai, Jakuen, and others, Sōtō Zen would grow beyond its initial mountain refuges, establishing a network of training monasteries and temples that carried forward the spirit of Dōgen’s teaching into the medieval Japanese world.

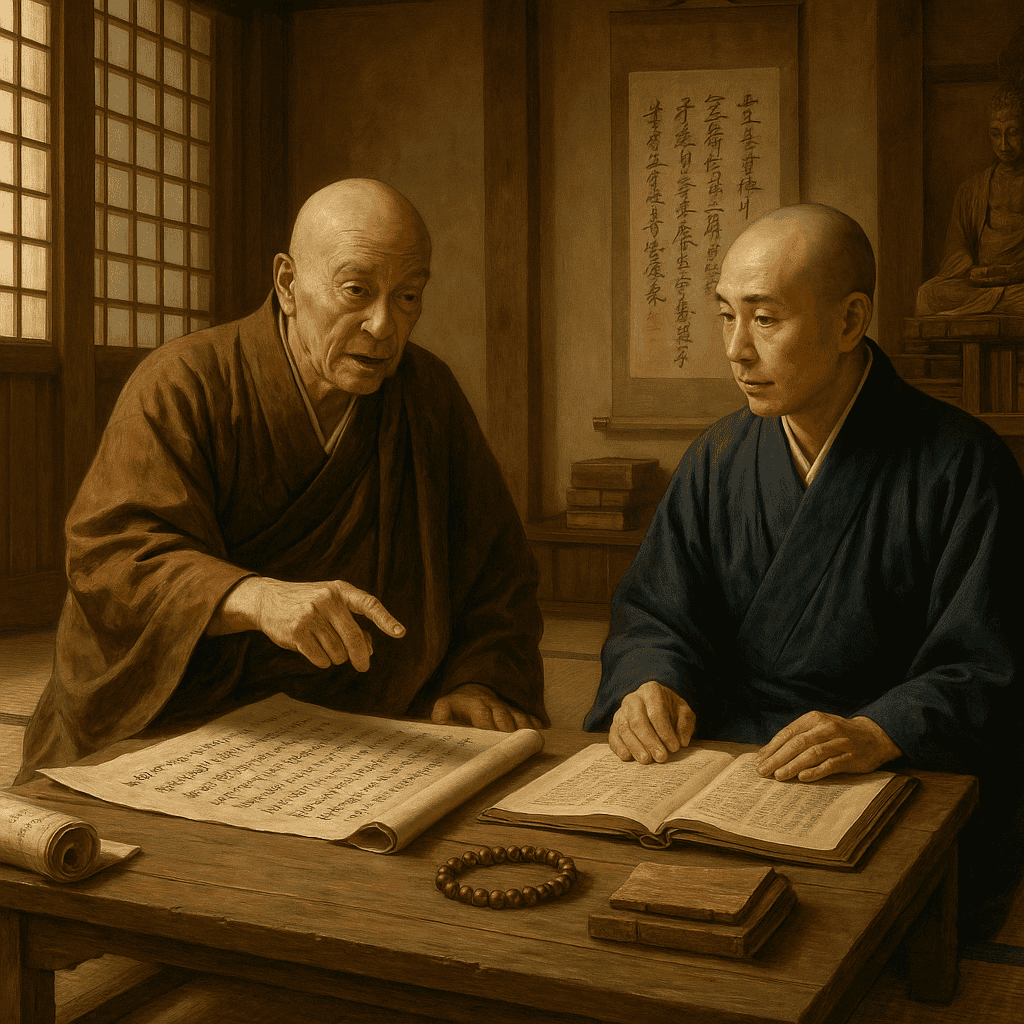

Early Sōtō Zen Monasticism After Dōgen

After Dōgen’s death in 1253, the fledgling Sōtō Zen community entered a period of consolidation and transition. Leadership of Eihei-ji passed to Koun Ejō (1200–1280), Dōgen’s closest disciple, who had trained under him for more than two decades. Ejō’s primary concern was to maintain the integrity of Dōgen’s teaching and to ensure the survival of the monastic community in a time of political uncertainty and religious competition.

Under Ejō’s guidance, Eihei-ji continued to follow the monastic standards set forth in the Eihei Shingi. Daily life centered around zazen, the observance of monastic discipline, work practice (samu), and the ritual forms inherited from Dōgen’s adaptations of Chinese Chan customs.

Ejō also undertook the important task of recording and preserving Dōgen’s oral teachings, compiling the Shōbōgenzō zuimonki (“Record of Things Heard”), a valuable collection of Dōgen’s informal talks and practical instructions.

However, the early Sōtō community was not without difficulties. Internal disagreements arose concerning the strictness of monastic practice and the relationship between the monastic community and lay society.

Tettsū Gikai (1219–1309), a disciple of both Dōgen and Ejō, advocated for broader reforms that would allow Sōtō Zen to adapt to the realities of rural Japan. Gikai envisioned a model of temple life that could accommodate lay patrons and village communities, ensuring the material support necessary for monastic survival.

This tension between preserving the original purity of Dōgen’s vision and adapting to the practical needs of expansion would shape the development of Sōtō Zen for generations. Although some purists feared the dilution of strict practice, Gikai’s initiatives ultimately helped Sōtō Zen take root outside the isolated mountain monasteries and spread throughout provincial Japan.

Meanwhile, other disciples of Dōgen, such as Jakuen and Kangan Giin, established their own communities, each reflecting aspects of Dōgen’s teaching. Jakuen, who had trained alongside Dōgen in China and later served as his attendant at Eihei-ji, founded Hōkyō-ji in Echizen Province, a monastery dedicated to maintaining a more austere and secluded form of practice. Giin traveled to Kyushu, where he founded temples and spread Dōgen’s teachings among local samurai and village communities.

Throughout the late Kamakura period (1185–1333), the Sōtō school gradually expanded its network of temples, many of which were small, rural, and closely tied to the agricultural life of the countryside. Unlike the Rinzai school, which remained closely associated with the military and aristocratic elites of Kyoto and Kamakura, Sōtō Zen developed strong ties with local clans and commoners. This decentralized, community-based model allowed Sōtō Zen to grow steadily, if quietly, across Japan.

By the early fourteenth century, through the efforts of figures such as Keizan Jōkin (1268–1325), Sōtō Zen would enter a new phase of institutional expansion and popularization. Keizan’s approach, building upon the foundations laid by Ejō and Gikai, would transform Sōtō Zen from a small monastic community into one of the major Buddhist traditions of medieval Japan.

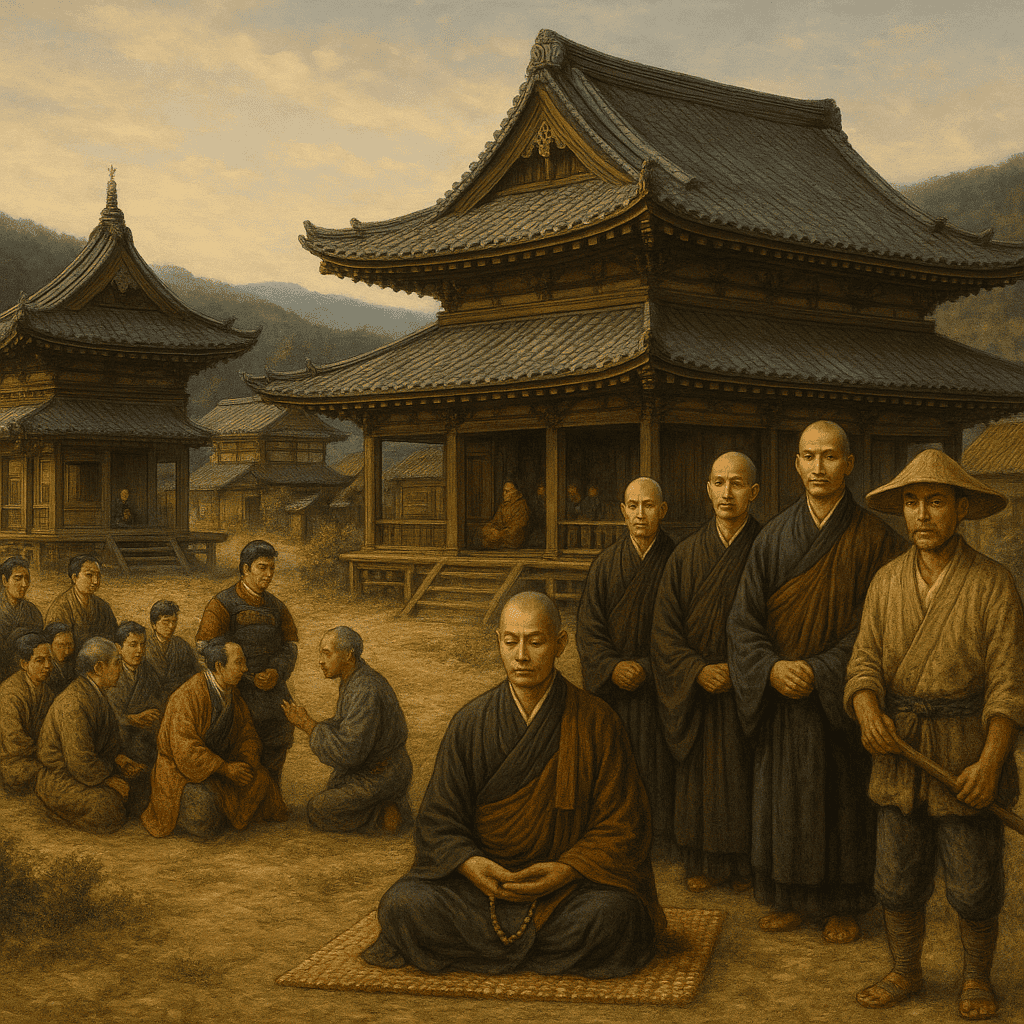

Keizan Jōkin and the Expansion of Sōtō Zen

The further establishment and popularization of Sōtō Zen in Japan owes much to the work of Keizan Jōkin (1268–1325), often referred to as the “second founder” of the school. Born into a family already sympathetic to Dōgen’s teachings—his grandmother was a disciple of Dōgen and his mother an abbess—Keizan entered monastic life at an early age. He trained at Eihei-ji and later under several leading figures of the early Sōtō community, including Tettsū Gikai and Jakuen.

Keizan’s vision for Sōtō Zen built upon the foundations laid by Dōgen, Ejō, and Gikai, but with an important new emphasis: the accommodation of lay practitioners alongside the maintenance of strict monastic training. Recognizing the realities of medieval Japanese society, Keizan worked to establish temples that could serve not only monks but also local communities, samurai patrons, and farming villages.

In 1294, Keizan founded Yōkō-ji in the mountains of Kanazawa. Later, in 1321, he assumed leadership of Sōji-ji, a temple that would become, alongside Eihei-ji, one of the two principal head temples of the Sōtō school. Through these institutions, Keizan formalized a model of temple organization that allowed for broader social engagement while preserving the essential practices of zazen, ritual observance, and ethical conduct.

Keizan also encouraged the system of temple branching (matsuji seido), wherein head temples would oversee a network of subordinate temples across the provinces. This strategy helped Sōtō Zen spread widely beyond its original mountain monasteries, creating a lasting institutional structure that supported both monastic and lay religious life.

In addition to his organizational work, Keizan composed important texts to support the training of monks and lay followers alike. His Transmission of the Light (Denkōroku), a collection of sermons recounting the lineage from Śākyamuni Buddha through Dōgen and beyond, provided a narrative framework that linked the Japanese Sōtō school directly to the ancient tradition of Chan masters in China.

By the time of Keizan’s death in 1325, Sōtō Zen had grown from a small and relatively isolated group into a vibrant network of temples and communities spread throughout Japan. His work ensured that Dōgen’s original spirit of practice could flourish across different social and regional contexts, laying the groundwork for Sōtō Zen’s enduring presence in Japanese religious life.

Key Early Sōtō Zen Monasteries

- Eihei-ji (永平寺)

Founded 1244 by Dōgen in Echizen Province; the original center of Sōtō monastic training. - Kōshōhōrin-ji (興聖法林寺)

Founded 1233 near Kyoto by Dōgen; an early attempt to establish an independent Zen community. - Hōkyō-ji (宝慶寺)

Founded c. 1261 by Jakuen in Echizen; a center preserving Dōgen’s strict style of monastic discipline. - Yōkō-ji (永光寺)

Founded 1294 by Keizan in Kanazawa; a key site for the training of monks and lay engagement. - Sōji-ji (總持寺)

Reestablished under Keizan’s leadership in 1321; became one of the two main head temples of the Sōtō school.

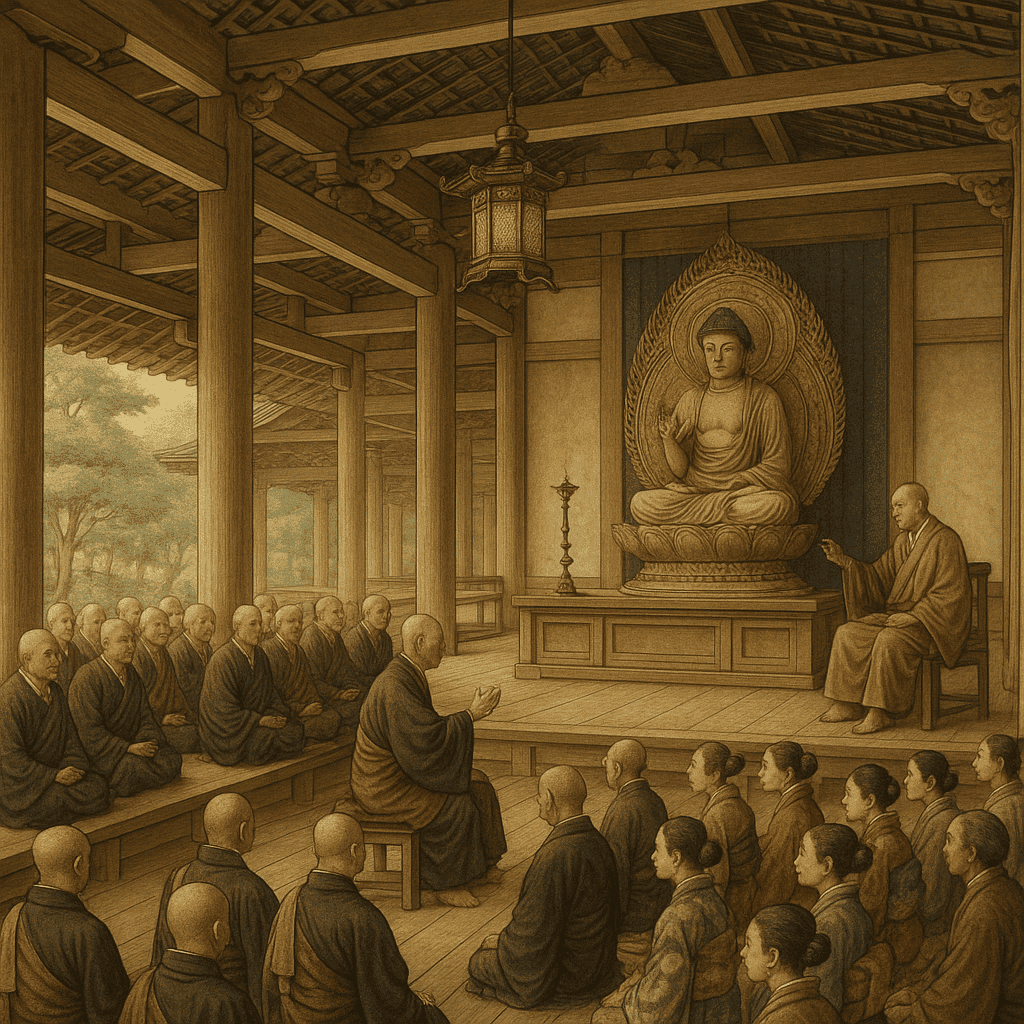

The Structure and Daily Life of Early Sōtō Zen Monasteries

Following the models established by Dōgen and Keizan, early Sōtō Zen monasteries developed a distinct organizational structure and daily rhythm centered on zazen, communal living, and mindful engagement with ordinary tasks. Drawing inspiration from Chinese Chan monastic codes, particularly the Chanyuan Qinggui, and adapting them to Japanese needs, Sōtō Zen monasteries emphasized simplicity, self-sufficiency, and the integration of practice into every aspect of life.

Monastic Organization

Monasteries were organized around a clear hierarchy of roles, each essential to the smooth functioning of the community. The abbot (jushoku) served as the spiritual and administrative head, responsible for guiding the sangha and maintaining the purity of practice.

Supporting the abbot were senior officers such as the prior (shuso), head cook (tenzo), work leader (ino), and chant leader (kansu). Each office carried not only practical responsibilities but also served as a form of spiritual training, emphasizing attentiveness, humility, and service.

Training monasteries maintained strict standards for admission. Novices entered after a period of probation, during which they demonstrated sincerity and a willingness to adapt to communal life. Full ordination followed, often accompanied by a formal ceremony of receiving the precepts (jukai).

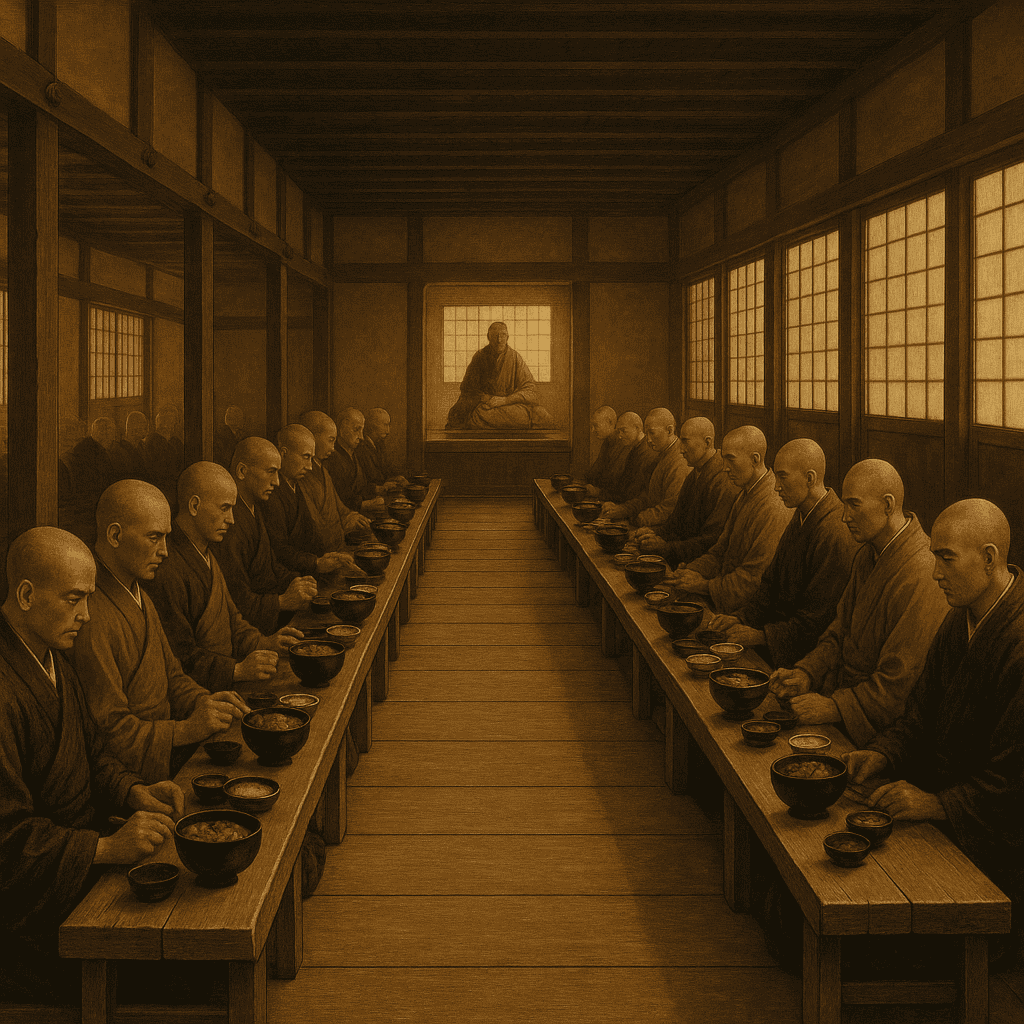

The Daily Schedule

The daily routine in early Sōtō monasteries was carefully structured to support continuous practice. Monks rose before dawn, gathering in the meditation hall (zendō) for the first session of zazen. Morning meditation was followed by chanting services, breakfast, and work practice. Manual labor (samu) — such as gardening, cooking, cleaning, or repairing buildings — was regarded as no less important than formal sitting meditation.

Midday included another period of meditation and a formal meal taken in the traditional oryoki style, emphasizing mindfulness and gratitude. Afternoons were often devoted to study, sutra copying, or further work duties, followed by evening chanting, meditation, and rest. Every action, from eating to walking to sleeping, was approached with the same mindful awareness cultivated in zazen.

The Meditation Hall

The meditation hall (zendō) formed the spiritual heart of the monastery. Monks each had an assigned seat (tan), a simple platform with a mat and cushion for seated meditation. In keeping with the spirit of equality and humility, seats were assigned without regard for social status, and monks maintained their space with care and simplicity. Silence was strictly observed in the zendō, reinforcing the monastery’s atmosphere of concentration and serenity.

Monastic retreats (sesshin) were held periodically, during which daily activities were pared down to intensive periods of zazen, broken only by brief rest, chanting, and meals. During these retreats, practitioners deepened their absorption and stabilized their minds through continuous sitting.

Temple Architecture

Sōtō monastery layouts followed Chinese Chan models but were often adapted to local conditions. A typical early Sōtō temple included the Butsuden (Buddha Hall) for ceremonies, the zendō (meditation hall), the kuri (kitchen complex), the bathhouse, and the guest hall. Buildings were usually simple wooden structures harmonizing with the natural environment, emphasizing the monastic ideals of modesty, harmony, and discipline.

Care was taken in the placement and construction of temple complexes, often situated near mountains, forests, or rivers. The surrounding natural setting was seen as an extension of the practice environment, encouraging contemplation of impermanence and interdependence.

Sample Daily Schedule in an Early Sōtō Monastery

- 3:30 AM — Wake-up bell (shōmyō)

- 4:00 AM — Early zazen (seated meditation)

- 5:30 AM — Morning chanting service (chōka)

- 6:00 AM — Breakfast (formal oryoki meal)

- 7:00 AM — Work practice (samu)

- 10:30 AM — Midday zazen session

- 11:30 AM — Main meal (formal oryoki lunch)

- 12:30 PM — Rest period or sutra study

- 2:00 PM — Work practice or personal practice (study, chanting, cleaning)

- 4:30 PM — Evening zazen session

- 6:00 PM — Light evening meal (optional in some monasteries)

- 7:00 PM — Evening chanting service

- 8:00 PM — Final zazen session or informal meditation

- 9:00 PM — Lights out and rest

This reflects a standard day based on Dōgen’s Eihei Shingi and early Sōtō customs — simple, rhythmic, and balanced between zazen, communal work, meals, study, and chanting.

The Sōtō School During the Muromachi Period

During the Muromachi period (1336–1573), Sōtō Zen underwent a period of steady growth and institutional stabilization. Building on the foundations laid by Dōgen, Keizan, and their immediate successors, the school expanded its network of temples across the Japanese archipelago, reaching deep into rural provinces and establishing itself among both warrior and farming communities.

One of the most significant developments during this era was the formalization of the head temple–branch temple system (honmatsu seido). Major centers such as Eihei-ji and Sōji-ji became official head temples (honzan), each overseeing a network of smaller branch temples (matsuji). This system provided a structure for regulating ordination, training, and the transmission of Dharma lineage, helping to maintain a degree of coherence across the expanding school.

The growth of Sōtō Zen during the Muromachi period was also closely tied to the patronage of local lords (daimyō) and influential village leaders. Unlike the Rinzai school, which was often associated with the cultural elite and the Ashikaga shogunate, Sōtō Zen found its base among provincial rulers and common people. Temples often served as centers of community life, offering not only religious services but also education, dispute mediation, and agricultural rites.

In adapting to regional needs, Sōtō Zen temples sometimes took on responsibilities beyond the strict bounds of monastic life. Many monks performed funerary rituals, ancestral memorial services, and other ceremonies important to the social and religious fabric of rural Japan. This practical engagement with everyday life enabled the school to sustain itself even as political instability and local warfare disrupted the established order.

During this period, Sōtō Zen maintained its emphasis on zazen and the everyday embodiment of the Dharma. While some adaptations were made to meet the needs of lay communities, leading monks and abbots continued to stress the centrality of meditation and ethical discipline in the training of priests.

The Muromachi period also saw the compilation of monastic codes and ritual manuals to ensure the uniformity of practice across temples. Documents such as the Shingi (rules of purity) were revised and circulated, providing clear standards for temple governance, monk conduct, and religious ceremonies.

By the end of the Muromachi period, Sōtō Zen had established itself as one of the largest and most geographically widespread Buddhist schools in Japan. Its combination of rigorous meditation practice, flexible adaptation to lay society, and decentralized organizational structure allowed it to weather the social upheavals of the era and to prepare for further growth in the centuries to come.

Key Developments of Sōtō Zen During the Muromachi Period

- Head Temple–Branch Temple System

Formal organization of Eihei-ji and Sōji-ji as head temples overseeing networks of branch temples across Japan. - Provincial Expansion

Growth of Sōtō temples into rural regions, supported by local lords (daimyō) and farming communities. - Lay Ritual Services

Performance of funerary rites, ancestral memorials, and community ceremonies by Sōtō priests, strengthening ties with local society. - Revision of Monastic Codes

Circulation of standardized Shingi (rules of purity) to regulate monastic conduct and ritual practices across the expanding network. - Enduring Emphasis on Zazen

Continued prioritization of seated meditation and ethical discipline despite broader engagement with lay religious life.

Sōtō Zen in the Edo Period

The Edo period (1603–1868) marked a time of profound transformation for Sōtō Zen, as it did for all of Japanese Buddhism. Under the centralized rule of the Tokugawa shogunate, Buddhism became deeply intertwined with the administration of the state. While this new relationship brought stability and support, it also reshaped the role of Sōtō Zen within Japanese society.

One of the most important policies affecting the Buddhist world during this time was the danka system (檀家制度). Under this system, every family in Japan was required to register with a Buddhist temple, which acted as both a religious center and a means of social control.

Temples were tasked with keeping records of births, deaths, and marriages, and with certifying the religious affiliation of the populace. In this context, Sōtō temples, with their strong local roots and experience in lay rituals, were well positioned to serve village communities across the country.

The danka system led to a massive expansion of Sōtō Zen’s reach. Thousands of small temples were founded or formalized, each serving a local network of lay families. Priests became community leaders as well as ritual specialists, responsible for performing funerals, memorial services, and other rites that were now integral to everyday social and religious life. In many cases, the performance of ritual services for lay patrons became the primary focus of temple life.

At the same time, monastic practice itself became increasingly regulated and systematized. Training monasteries (sōdō) were established where young monks underwent rigorous education in chanting, ritual forms, and etiquette, alongside the traditional practice of zazen. The head temples Eihei-ji and Sōji-ji maintained authority over ordination and certification, ensuring that priests met the standards required to serve their communities.

Philosophical study and commentary on Dōgen’s writings also flourished during the Edo period. Scholars such as Manzan Dōhaku (1636–1715) and Menzan Zuihō (1683–1769) worked to revive and clarify Dōgen’s original teachings, reaffirming the importance of zazen and reintroducing stricter interpretations of monastic discipline. Their efforts helped to counterbalance the increasingly ritualized character of everyday temple life.

Despite these reforms, the Edo period saw a gradual shift in emphasis within Sōtō Zen. For the majority of temples, the primary activities revolved around serving the laity through rites of passage and community festivals. While monastic training remained vital at major centers, the image of Sōtō Zen as a tradition rooted in everyday village life became firmly established.

By the end of the Edo period, Sōtō Zen had grown into the largest Buddhist school in Japan in terms of the number of temples and priests. Its ability to adapt to changing social conditions, while preserving its essential practices at core training centers, ensured its survival into the modern era.

Key Features of Sōtō Zen During the Edo Period

- Danka System (檀家制度)

Every family was required to register with a Buddhist temple, integrating temples into the administrative structure of the Tokugawa state. - Expansion of Local Temples

Thousands of Sōtō temples served rural and village communities, performing funerary and memorial rites. - Monastic Training Centers

Formal training monasteries (sōdō) were established, systematizing the education of priests in ritual, etiquette, and zazen. - Revival of Dōgen Studies

Scholars such as Manzan Dōhaku and Menzan Zuihō emphasized the return to Dōgen’s original teachings and stricter monastic standards. - Shift Toward Lay Ritual Focus

Daily life in many temples centered on serving the laity, while formal zazen training continued primarily at designated monasteries.

Sōtō Zen in the Meiji Period and Modern Era

The transition from the Edo to the Meiji period (1868–1912) brought profound upheaval to Japanese Buddhism. With the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate and the restoration of imperial rule, Japan embarked on a rapid program of modernization and Westernization.

As part of this transformation, the new government promoted Shinto as the state religion and launched a policy of separating Shinto and Buddhism (shinbutsu bunri), followed by widespread anti-Buddhist sentiment known as haibutsu kishaku (“abolish Buddhism and destroy Shākyamuni”).

Many Buddhist temples were closed, landholdings confiscated, and monks forced to return to secular life. Sōtō Zen, like all Buddhist schools, suffered heavy losses. Numerous rural temples disappeared, and the authority of head temples such as Eihei-ji and Sōji-ji was weakened. At the same time, the government redefined the role of Buddhist clergy, encouraging monks to marry, eat meat, and participate fully in secular society — a dramatic break from centuries of celibate, monastic tradition.

Faced with these challenges, the Sōtō school undertook reforms to adapt to the new realities of Meiji Japan. Efforts were made to modernize education for monks, establish lay organizations, and redefine the role of temples within society. Sōtō Zen leaders worked to present Buddhism as compatible with the values of a modern nation-state, emphasizing moral education, social harmony, and national loyalty.

Despite initial setbacks, Sōtō Zen gradually stabilized during the late Meiji period and early twentieth century. Lay organizations grew in importance, and temples once again became centers of local community life. Meanwhile, formal monastic training continued at major centers such as Eihei-ji and Sōji-ji, preserving the essential practices of zazen, ritual observance, and communal living.

The twentieth century also witnessed the spread of Sōtō Zen beyond Japan. Following World War II, Sōtō teachers began to establish temples and meditation centers in the West. Figures such as Shunryū Suzuki (1904–1971), founder of the San Francisco Zen Center, introduced traditional Sōtō practices to new audiences, emphasizing zazen as the heart of Zen training. Other teachers, such as Taisen Deshimaru in Europe and Dainin Katagiri in the United States, helped to build international Sōtō communities.

In contemporary Japan, Sōtō Zen remains one of the largest Buddhist schools, with more than 14,000 temples nationwide. While many temples serve primarily as centers for funerary rites and memorial services, a strong tradition of meditation practice and monastic training endures. Eihei-ji and Sōji-ji continue to function as central training monasteries, upholding the spirit of Dōgen’s original vision.

Globally, Sōtō Zen has taken root in diverse cultural contexts, adapting its traditional forms while maintaining the central emphasis on zazen, mindful living, and the unity of practice and realization. Through cycles of upheaval and renewal, Sōtō Zen remains a living tradition, bearing witness to the enduring relevance of Dōgen’s teaching in the modern world.

Key Modern Developments in Sōtō Zen

- Haibutsu Kishaku (廃仏毀釈)

Anti-Buddhist persecution during the early Meiji period; loss of temples, land, and traditional monastic privileges. - Clergy Reforms

Monks permitted to marry and eat meat; shift from celibate monastic ideal to clerical participation in lay society. - Modernization of Education

Establishment of Buddhist seminaries and schools to train priests in both traditional teachings and modern disciplines. - Growth of Lay Organizations

Expansion of lay groups supporting temple activities and social services, strengthening community ties. - International Spread

Establishment of Sōtō Zen centers in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere after World War II, bringing zazen practice to a global audience. - Preservation of Monastic Practice

Continued maintenance of formal training monasteries at Eihei-ji and Sōji-ji, upholding Dōgen’s emphasis on zazen and communal discipline.

Shikantaza and Kōan Practice: Two Approaches to Zen Training

Within the various streams of Zen Buddhism, two primary approaches to meditation have developed: shikantaza (“just sitting”) and kōan practice (contemplation of paradoxical dialogues or questions). Although both methods aim at awakening to one’s true nature, their methods and emphases differ, reflecting the unique spirit of each lineage.

Shikantaza: The Practice of “Just Sitting”

Shikantaza (只管打坐) — a central practice in the Sōtō Zen tradition — was most clearly articulated by Eihei Dōgen. In shikantaza, the practitioner engages in seated meditation without the use of objects, anchors, mantras, or philosophical inquiry. There is no striving for realization, no conceptual focus, no solving of riddles. Instead, the practitioner sits upright in stillness, allowing thoughts, sensations, and emotions to arise and fall away naturally, without attachment or aversion.

Dōgen emphasized that shikantaza is not a method to attain enlightenment but the actualization of enlightenment itself. Sitting is not preparation for awakening; it is the direct embodiment of awakening, here and now. In Dōgen’s words, “Practice and realization are not two.” Shikantaza invites the practitioner to trust deeply in the inherent completeness of the present moment, abandoning all subtle seeking and resting fully in “being-time” (有時, uji).

This practice embodies the character of Sōtō Zen — patient, understated, and quietly radical — a way of living in profound accord with the impermanent, flowing nature of existence.

Kōan Practice: The Way of Inquiry and Penetration

In contrast, kōan practice developed most strongly within the Rinzai Zen tradition, though it has roots in the earlier Chinese Chan tradition shared by all Zen schools. A kōan (公案) is a brief story, dialogue, or question, often paradoxical, intended to cut through rational thought and provoke a direct experience of awakening.

In kōan practice, a student typically works intensively with a teacher, meditating on a single kōan — such as “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” or “What was your original face before your parents were born?” Through sustained concentration and repeated encounters with the teacher, the practitioner is pressed to break through habitual thinking patterns and experience reality directly.

Kōan practice is dynamic and often intense, designed to challenge the ego’s tendency to grasp, interpret, and seek control. It emphasizes sudden insight (kenshō) and may involve hundreds of kōans in progressive stages of training.

Two Complementary Paths

Although often seen in contrast, shikantaza and kōan practice ultimately point toward the same truth: the awakening beyond conceptual thought, the realization of the Buddha-nature inherent in all beings. Both traditions recognize that intellectual understanding alone cannot lead to liberation; only direct, embodied realization can.

In historical Japan, the distinction between the two approaches became institutionalized, with Sōtō Zen focusing on the quiet stability of shikantaza and Rinzai Zen emphasizing the dynamic confrontation of kōan inquiry. Yet in practice, many Zen teachers have encouraged flexibility, recognizing that different dispositions and circumstances may call for different methods.

At its heart, whether through the open stillness of shikantaza or the fierce penetration of kōan practice, Zen calls the practitioner to return fully to the reality of this moment — empty, vivid, and complete.

Origins of Shikantaza

In the Chan Buddhist tradition descending from Gautama Buddha, Bodhidharma, and Huineng, the practice known as Silent Illumination (mozhao chan) does not involve the suppression of thought, the extinguishing of emotion, or the arresting of the mind’s natural functions. It is not a visualization of emptiness, a contemplation of cosmic principles, nor a rejection of enlightenment as a goal or cultivation as a means.

Silent Illumination is simply calm, non-reactive awareness, allowing thoughts and sensations to arise and pass away naturally. The deliberate effort of concentration and intentional striving is replaced by the non-effort of a purposeless, open mind.

Silent Illumination and Hongzhi Zhengjue

One of the most refined expressions of Chinese Chan meditation to emerge during the Song dynasty was the practice of Silent Illumination (默照禪, mozhao chan). This contemplative method emphasizes non-conceptual awareness and the merging of stillness (mo, silence) with clarity (zhao, illumination). It is a meditation of natural, non-interfering presence, free from striving, in which the practitioner rests in undivided awareness of all phenomena—neither clinging nor rejecting.

The foremost exponent of this practice was Hongzhi Zhengjue (宏智正覺, 1091–1157), a revered Chan master of the Caodong (Sōtō) lineage. Hongzhi served as abbot of Jingde Monastery on Mount Tiantong, located in Ming Province (modern-day Zhejiang). This same monastery would later be led by Tiantong Rujing (1163–1228), the teacher of Dōgen Zenji, founder of the Japanese Sōtō school.

Hongzhi’s teachings, preserved in texts such as “Cultivating the Empty Field”, describe a meditation of luminous openness—resembling the still mirror or the vast sky—where clarity arises naturally from the still ground of mind. This view would profoundly influence both Rujing and Dōgen. Although Dōgen would later emphasize the term shikantaza (“just sitting”) to distinguish his teaching, Silent Illumination remains one of the deepest roots of his approach to practice.

The abbot Tiantong Rujing (1163–1228), under whom Dōgen trained in China, coined the phrase shikan-taza (只管打坐) — meaning “nothing but just sitting” — to describe the distilled essence of this practice. In shikantaza, there is no deliberate thought, no visualization, no contemplation of kōans, and no counting of the breath. It is a direct re-enactment of the Buddha’s own sitting beneath the Bodhi tree, embodying the spirit of awakening without seeking or striving.

For Dōgen, there was no separation between the practice of shikantaza and the realization of enlightenment. Practice and awakening are one (shushō ittō). Shikantaza is not a method to achieve Buddhahood; it is the actualization of the Buddha-nature already present. When sincerely practiced, it is the dropping away of body and mind (shinjin datsuraku), the natural revealing of one’s original, awakened nature.

Dōgen’s teaching of shikantaza reflects the spirit of Huineng’s “sudden enlightenment” school, where awakening is immediate and complete. There is no gradual cultivation of ethics, meditation, or wisdom to acquire something external; rather, these qualities are already fully present in one’s essential nature. In Dōgen’s view, the beginner and the adept alike, when sitting zazen with sincerity, equally embody the awakened mind.

Keizan Jōkin, in his Zazen Yōjinki (“Notes on What to Be Aware of in Zazen”), echoed this principle, referring to the realization of one’s Original Face and Original Nature — a formless, ineffable observer that transcends bodily senses, moral discrimination, and even the dualities of enlightenment and delusion.

The philosophical background of Dōgen’s meditation training also includes the influence of Zhiyi (538–597), founder of the Tiantai school in China (Tendai in Japan). Zhiyi’s Lesser Treatise on Concentration and Insight (Xiao Zhiguan) and Great Treatise on Concentration and Insight (Mohe Zhiguan) systematized Buddhist meditation by integrating samatha (calm abiding) and vipassana (insight).

His methods often involved contemplations on emptiness and the gradual suppression of deluded thoughts, closely paralleling the Vipassanā tradition of early Buddhism.

In contrast, the Zuochan Yi (“Principles of Seated Meditation”) attributed to Changlu Zongze (d. c. 1107), which strongly influenced Dōgen, arose from the East Mountain teachings of Daoxin and Hongren in seventh-century Chan. While these teachings retained elements of object-focused meditation, Zongze emphasized a passive, lucid awareness — allowing thoughts to arise and dissolve naturally without judgment, eventually forgetting all mental objects and entering unity of mind.

Where Zhiyi’s Tiantai system cultivated deliberate contemplation, Zongze’s approach moved closer to the effortless mindfulness that would come to define shikantaza. In this, it shares much in spirit with the Daoist ideal of wu-wei (“non-action”), where the practitioner rests in the natural unfolding of mind and phenomena, untouched by grasping or resistance.

Thus, shikantaza emerged as the refined expression of centuries of Chinese Buddhist meditation development, embodying a return to the original simplicity of silent sitting — a practice neither seeking realization nor abandoning it, but abiding calmly in the very ground of awakening itself.

Interpreting Shikantaza

In the Eihei Kōroku, Eihei Dōgen discusses the role of the breath in meditation. He records that his Chinese teacher, Tiantong Rujing, taught that the breath arises from and returns to the cinnabar field (dantian) — the energy center in the lower abdomen recognized in Chinese internal practices.

However, Dōgen specifically dismisses meditation techniques such as counting the breath or focusing on its length and quality. Instead, he emphasizes a more natural approach, consistent with the teachings of Zongze: with steady concentration, “objects are forgotten” and the mind “becomes unified.” The aim is to foster a state of relaxed awareness and quiet joy, sustaining this lucid, effortless presence throughout all activities of the day.

One of Dōgen’s most frequently referenced examples appears in the Zazen Shin chapter of the Shōbōgenzō, drawing from a story about the Tang dynasty Chan master Yaoshan Weiyan (Japanese: Yakusan Igen):

A monk asked, “What are you thinking of, sitting there so still?”

Yaoshan replied, “I am thinking of not thinking.”

The monk pressed, “How do you think of not thinking?”

Yaoshan answered, “Non-thinking.”

Here, Yaoshan’s reply points not to the content of thought, nor to its suppression, but to a state of pure, open awareness — what Dōgen would later characterize as hishiryō (“non-thinking”). Thoughts and feelings naturally arise and dissolve within an open field of mindfulness, without deliberate effort or judgment. Volition and attention are lightly but steadily maintained, forming a state of clear, expansive consciousness.

In his final revision of the Fukanzazengi, Dōgen refines this understanding further. Earlier instructions to “forget objects” give way to the language of “non-thinking” — an even more subtle and immediate expression of the attitude in zazen. Dōgen’s terminology distinguishes:

- Shiryō (思量) — “thinking”

- Fushiryō (不思量) — “not thinking”

- Hishiryō (非思量) — “non-thinking”

The negating prefixes (fu and hi) suggest different shades of meaning, but in practice, Dōgen points beyond linguistic distinctions. Non-thinking is neither conscious intellectual effort nor unconscious passivity. It is an alert, non-grasping presence that neither clings to nor suppresses the movements of mind.

In shikantaza, thoughts arise and pass without conscious direction. This natural state of mind is the ground for what Dōgen describes in Shōbōgenzō Zanmai ō Zanmai as the sloughing off of body and mind (shinjin datsuraku), a letting-go that reveals one’s inherent Buddha-nature. Practice and enlightenment are unified — not as cause and effect, but as one undivided reality. Thus, shikantaza is not a means to an end; it is simply the expression of awakened being itself.

Yet shikantaza does not imply a lack of intention, concentration, or mindfulness. The intention is to realize the cessation of suffering by embodying the Buddha Way. It reflects adherence to the Eightfold Path, particularly Right Concentration and Right Mindfulness.

Dōgen’s teaching that one should “act as a Buddha” means that the state of shikantaza is not limited to formal sitting; it can be actualized in every activity, every moment. In Dōgen’s view, this transmission of the awakened mind has continued face-to-face from Śākyamuni Buddha through the unbroken Zen lineage.

Shikantaza may also be compared to the state known as no-mind (wuxin 無心 in Chinese, mushin 無心 in Japanese) — an effortless awareness free from clinging and conceptual elaboration. In embodying perfect enlightenment, shikantaza directly expedites the realization of awakening. Just as sleep is approached by “pretending to be asleep,” awakening is approached by sitting as if already awakened, entering the field of non-striving.

Dōgen’s Fukanzazengi thus reads less as a technical manual and more as a poetic invocation, firmly rooted in the Silent Illumination tradition but uniquely expressed through Dōgen’s language and vision. His teaching preserves the heart of Buddhism’s ancient path: the union of ethics (śīla), wisdom (prajñā), and meditation (dhyāna).

Like Zhiyi, Zongze, and the early Indian Buddhists, Dōgen affirms that the purpose of meditation is the realization of samādhi — the deep absorption beyond deluded thinking — as the gateway to true enlightenment.

At its core, the practice of shikantaza is an enduring form of Illumination meditation, a path validated not only by ancient wisdom but increasingly recognized by modern science under the name of mindfulness: the cultivation of conscious, compassionate presence in the unfolding moment.

The Living Tradition of Soto Zen

From its beginnings as a small monastic community in the remote mountains of medieval Japan, Sōtō Zen has grown into one of the most enduring and widespread forms of Japanese Buddhism. Guided by the teachings of Eihei Dōgen and the organizational vision of Keizan Jōkin, Sōtō Zen preserved the central practice of zazen while adapting to the needs of different historical eras — from the decentralized villages of the Kamakura period to the complex social structures of modern Japan and the global community beyond.

Throughout these transformations, the heart of Sōtō Zen has remained the same: the realization that awakening is not apart from daily life, but found within it — in sitting quietly, in working diligently, in living with mindfulness and humility. The simplicity and depth of this teaching continue to offer a path of practice for those who seek a direct, authentic experience of the Buddha’s Way.

Today, from the mountain temples of Eihei-ji and Sōji-ji to meditation halls across the world, the quiet spirit of Sōtō Zen endures, carrying forward a lineage of practice that speaks across centuries to the human longing for clarity, compassion, and peace.

D. B. Smith

Curator · Freemason · Zen Practitioner · Founder of Science Abbey

D. B. Smith is an American historian, curator, and author whose life bridges the contemplative practices of East and West. A Master Mason and 32° Scottish Rite Freemason, he served as Librarian and Curator at the George Washington Masonic National Memorial in Alexandria, Virginia, where he managed rare Masonic archives and artifacts linked to George Washington himself. His work included collaboration with leading fraternal scholars and global Masonic leaders.

Smith was initiated into the Lodge of the Nine Muses No. 1776, an elite esoteric lodge in Washington, D.C., founded by past masters of George Washington’s own lodge. He has enjoyed ritual and fellowship in both national and international Masonic circles.

In parallel with his Western initiatic training, Smith received the Dharma name “Wu Yi,” or “Mui,” (“Depends on Nothing”) from a Korean Jogye Order monk in 2004. Today he is a lay practitioner in Soto Zen Buddhism, training under lineages rooted in Eihei Dogen Zenji and Dainin Katagiri Roshi, including participation in the Iowa City Zen Center and the Ryumonji Zen Monastery in the American Midwest.

He is the founder of Science Abbey, an independent research and educational platform that explores the intersection of mysticism, science, ritual, and philosophy. His work encourages a modern contemplative life grounded in historical wisdom traditions, transdisciplinary learning, and global spiritual citizenship.