From the forests of India to the streets of São Paulo, the journey of the Dharma across continents and cultures

Table of Contents

- The Spread of Buddhism in Asia

From the Buddha’s enlightenment to the formation of distinct Asian traditions

The Arrival of Buddhism in Europe

From classical curiosity to modern communities - Pioneers of the Dharma in the West

Schopenhauer, Ananda Metteyya, U Dhammaloka, and the first Western Buddhists - Post-War Institutions and Teachers in Europe

Tibetan lamas, Zen masters, and the Western sanghas they inspired - The Spread of Buddhism in Africa

Temples, immigrant communities, and emerging local practice - The Spread of Buddhism in the Americas

From immigrant temples to countercultural Zen and mindful modernity - The Spread of Buddhism in Australia and Oceania

From gold-rush temples to thriving, diverse modern sanghas - Conclusion: A Global Dharma

The Buddha’s legacy as a planetary possibility

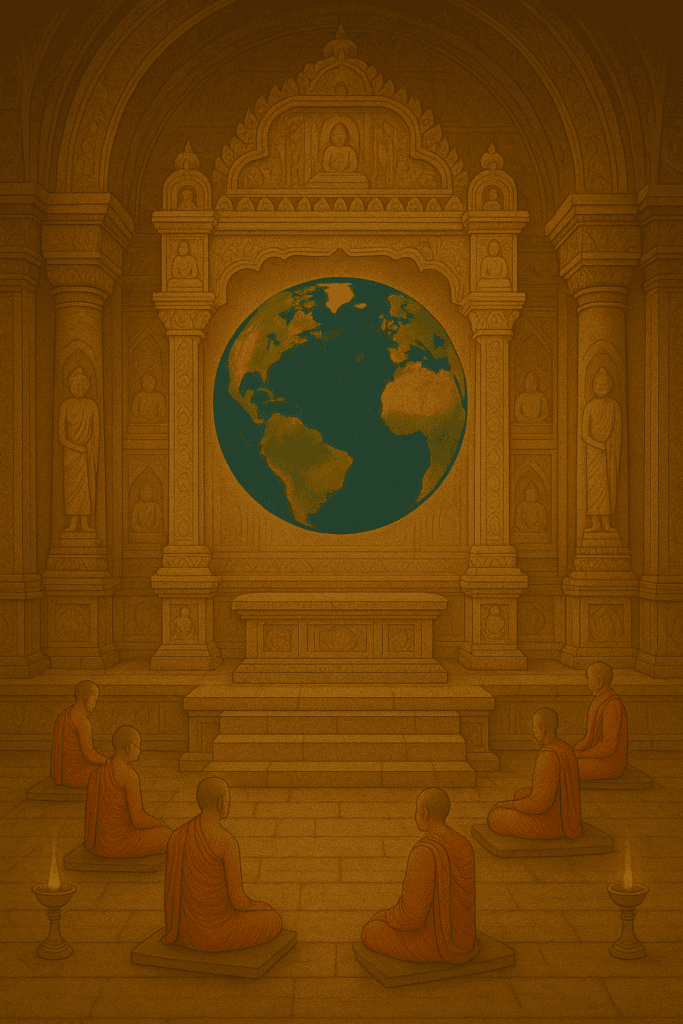

Introduction: The Movement of Stillness

Buddhism began not with a conquest, but with a quiet. One man, seated in meditation beneath a fig tree, touched the Earth and awakened—not to a new religion, but to a timeless truth: that suffering exists, that its causes can be understood, and that there is a path to freedom.

From that stillness, movement began. Not political expansion or missionary fervor, but the movement of minds, hearts, and conversations. Over two and a half millennia, the teachings of the Buddha—rooted in impermanence, interdependence, and compassion—have journeyed with merchants, monks, refugees, artists, scientists, and seekers across every continent on Earth.

What makes this story remarkable is not just the geographic spread of Buddhism, but its capacity to adapt without losing its essence. Whether expressed in ancient Pāli chants or in modern psychological language, the Dharma has retained its “one taste”—the taste of liberation. In every land it enters, Buddhism has learned the local tongue, woven itself into native customs, and transformed those who practice it without requiring rigid conformity.

This article traces that global journey, beginning with the Buddha’s lifetime and spreading outward across Asia, Europe, Africa, the Americas, and Oceania. Along the way, we will meet monks and philosophers, poets and political exiles, scientists and mystics—each carrying a piece of the Dharma and leaving a unique imprint in return.

What emerges is not a map of expansion, but a mandala of human transformation—a testament to the power of an idea whose time never seems to pass.

The Spread of Buddhism in Asia

Buddhism originated in the northeastern Indian subcontinent during the 5th to 4th century BCE with the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, known as the Buddha. From its earliest days, the Buddhist tradition emphasized the transmission of teachings through community, dialogue, and patronage, allowing it to spread rapidly beyond its birthplace.

India and the Mauryan Empire: The initial spread occurred through the establishment of monastic communities (sanghas) and the oral transmission of teachings. The most significant early expansion came under Emperor Ashoka of the Mauryan Empire in the 3rd century BCE.

After converting to Buddhism, Ashoka actively promoted the faith across his realm and beyond. He sent missions to regions such as Sri Lanka, Gandhara, and Central Asia, and inscribed Buddhist edicts across the subcontinent.

Sri Lanka and South Asia: Mahinda, traditionally considered Ashoka’s son, led a mission to Sri Lanka, where Buddhism took deep root, eventually becoming the dominant religion. From there, it expanded to the Maldives and Southeast Asia. Over centuries, Sri Lanka developed into a major center for Theravāda Buddhism, preserving early scriptures and monastic codes.

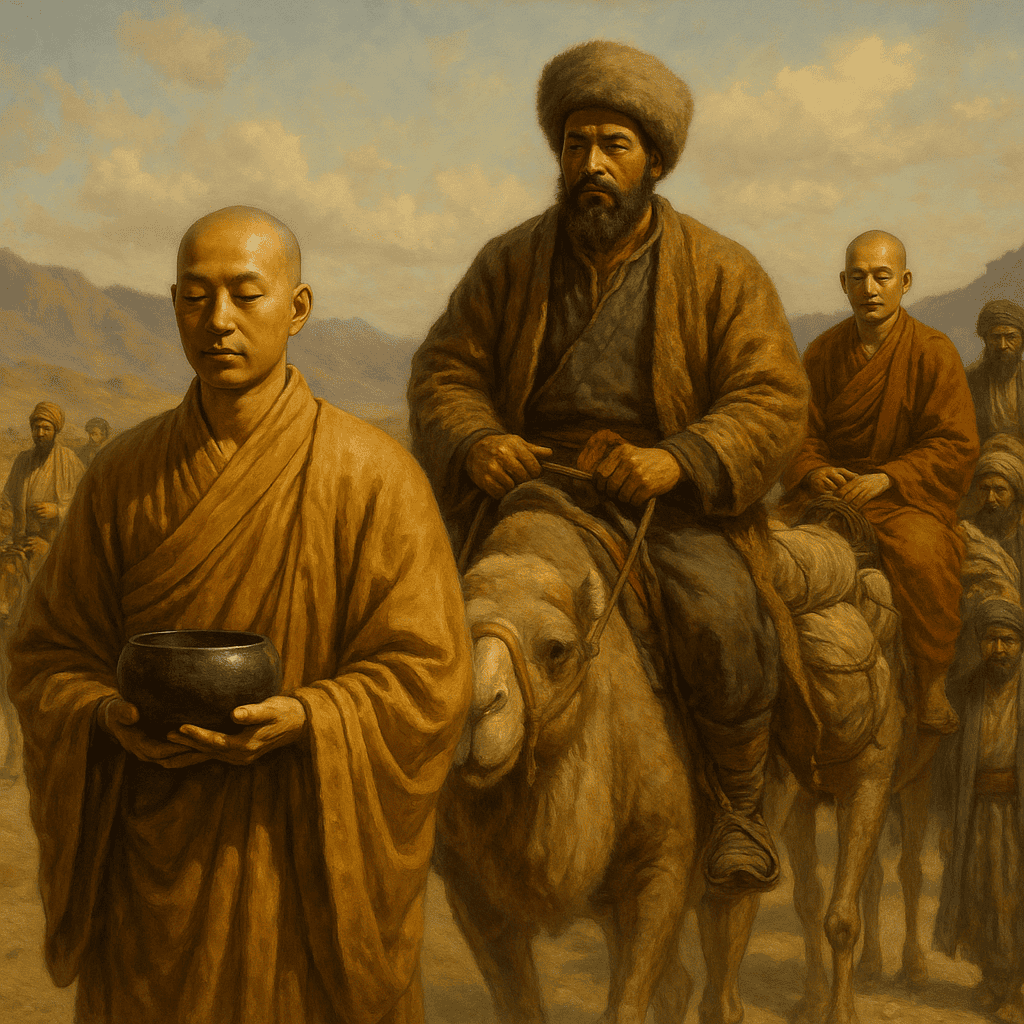

Central Asia and the Silk Road: As trade flourished along the Silk Road, Buddhist monks and merchants carried the teachings through Central Asia. By the 1st century CE, Buddhist communities had been established in Bactria, Sogdia, and other key caravan cities. These regions became vibrant centers of Buddhist translation, art, and intercultural exchange.

China: Buddhism entered China via the Silk Road around the 1st to 2nd century CE. Initially interpreted through Daoist and Confucian lenses, it evolved into diverse schools, including Tiantai, Huayan, Pure Land, and Chan (Zen). Chinese monks like Xuanzang made pilgrimages to India to collect texts and return them for translation and teaching, facilitating a profound integration into Chinese religious life.

Korea and Japan: From China, Buddhism was introduced to Korea by the 4th century CE, where it was adopted by royal courts and aristocratic elites. Korean monks contributed significantly to the development of East Asian Buddhism. By the mid-6th century, Buddhism had reached Japan, becoming a cornerstone of court culture, ritual, and monastic organization. Over time, Zen, Pure Land, and esoteric forms of Buddhism flourished in Japan.

Tibet and the Himalayan Regions: In the 7th century, Buddhism began to take hold in Tibet, blending with indigenous Bon traditions. Tibetan Buddhism developed unique philosophical, ritual, and institutional features, becoming a powerful cultural and political force across the plateau and in neighboring regions like Bhutan, Nepal, and Mongolia.

By the close of the first millennium CE, Buddhism had established deep roots across much of Asia, shaping cultures, literatures, statecraft, and spiritual life. It would take many more centuries—and significant modern transformations—for it to spread across the globe.

The Arrival of Buddhism in Europe

Though Buddhism was known to some in the ancient Greco-Roman world through distant trade and limited philosophical contact, it was not until the modern era that it gained real presence in Europe. The spread to Europe unfolded in stages—first through intellectual curiosity and academic scholarship, then through practice and community formation.

Early Encounters and Classical Curiosity: As early as the 3rd century BCE, following the campaigns of Alexander the Great in Central Asia, limited contact between Hellenistic and Buddhist cultures occurred. Greek-influenced Buddhist art in Gandhara and philosophical syncretism, such as between Greek skepticism and Buddhist thought, suggest mutual awareness, though not widespread influence.

Renaissance and Enlightenment Europe: European awareness of Buddhism began to expand in the 17th and 18th centuries, when Jesuit missionaries returning from Asia and Enlightenment thinkers began to study Asian religions. Buddhist doctrines were often misunderstood or framed through Christian or classical lenses, portrayed as either nihilistic or atheistic.

19th-Century Orientalism and Scholarship: The 19th century saw a surge in European interest in Buddhism, driven by colonial encounters in South and Southeast Asia. German, French, and British scholars translated Pali and Sanskrit texts, founding the academic discipline of Buddhist Studies. Figures such as Eugène Burnouf in France and T.W. Rhys Davids in Britain shaped early European interpretations, often emphasizing a rational, ethical core over ritual and devotion.

Pioneers of the Dharma in the West

Philosophical Forebears: Arthur Schopenhauer

One of the earliest and most influential European thinkers to engage with Buddhist philosophy was German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860). Deeply influenced by translations of Indian texts and concepts of suffering, impermanence, and detachment, Schopenhauer praised Buddhism as a rational and ethical religion.

While he never formally converted, his metaphysics, especially the idea of the “will” and his bleak view of existence, drew comparisons with Buddhist ideas of dukkha (suffering) and nirvāṇa (release). Schopenhauer’s esteem for Buddhism helped spark 19th-century philosophical interest in the East.

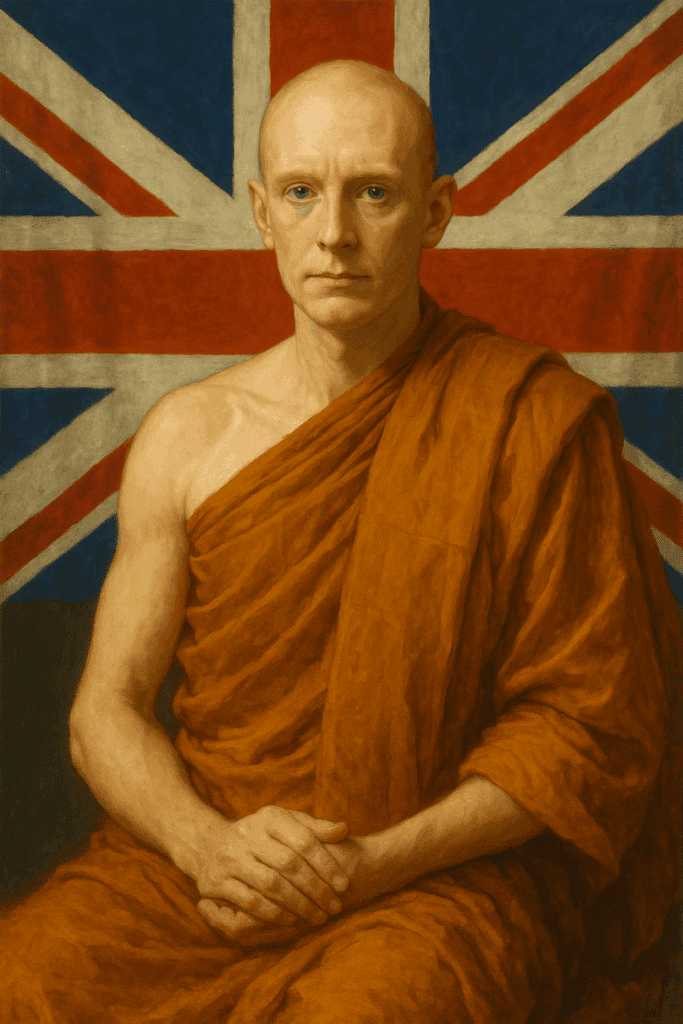

The First European Buddhist Monk: Charles Henry Allan Bennett (Ananda Metteyya)

Charles Henry Allan Bennett (1872–1923), a British-born mystic and member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, became one of the first Westerners to ordain as a Theravāda Buddhist monk. Taking the name Ananda Metteyya, he traveled to Burma in the early 1900s and studied deeply in the monastic tradition.

In 1908, he returned to Britain as part of a Buddhist mission, founding the British Buddhist Society and publishing The Buddhist Review, the first Buddhist journal in Europe. His work marked the beginning of organized Buddhist activity in the UK and inspired further Western interest in Buddhist practice and ethics.

A Radical Pioneer: U Dhammaloka (Laurence Carroll)

Among the most colorful early European Buddhists was U Dhammaloka, born Laurence Carroll in Ireland or the U.S. in the 1850s. A working-class migrant and atheist, he was ordained as a monk in Burma in the 1880s or 1890s, becoming one of the first Westerners to do so.

U Dhammaloka became known for his radical anti-colonial sermons and public debates with Christian missionaries, advocating Buddhism as a religion of reason, ethics, and cultural resistance. He traveled widely in Asia, including India and Japan, and represents an early form of socially engaged Western Buddhism.

Theosophists and Buddhist Romanticism

In parallel with these more committed figures, the late 19th-century Theosophical Society—founded by Helena Blavatsky and Henry Steel Olcott—championed a romanticized and syncretic vision of Buddhism.

While their interpretation often blended Buddhist terms with esoteric Western metaphysics, Olcott in particular worked closely with Sinhalese Buddhists and helped design the Buddhist flag. Their public support for Buddhism during colonial times contributed to its growing legitimacy in the West.

These early European Buddhists helped catalyze Western awareness of Buddhist thought, whether through philosophical admiration, spiritual commitment, or political action. Their lives marked the transition from academic curiosity to embodied practice—laying the groundwork for later waves of Buddhist interest, community-building, and institutional presence in Europe.

20th-Century Immigration and Conversion: The 20th century brought Buddhist immigrants from China, Japan, Vietnam, and Tibet to Europe, particularly after World War II and following geopolitical upheavals such as the Chinese invasion of Tibet.

These communities established temples and centers, especially in the UK, France, and Germany. Simultaneously, interest in meditation and Zen among European intellectuals and artists led to the formation of Euro-American convert communities.

Post-War Buddhist Institutions and Teachers in Europe

Following World War II, Europe experienced a quiet but significant Buddhist renaissance. The devastation of the war, the questioning of traditional religious structures, and the influx of Asian migrants and exiled teachers created fertile ground for the establishment of new Buddhist institutions.

These post-war decades saw the emergence of both immigrant and convert communities, new monastic centers, lay networks, and influential teachers who reshaped Buddhism for European contexts.

Tibetan Diaspora and Vajrayāna Foundations

After the 1959 Chinese annexation of Tibet, many lamas fled into exile. Some, like the 16th Karmapa and later the Dalai Lama himself, made visits to Europe, establishing Buddhist centers and teaching Vajrayāna to Western students.

In Switzerland, France, and the UK, early Tibetan centers were founded with the help of figures like Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche, and organizations such as the Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition (FPMT) began to train European practitioners in Tantric and Mahāyāna practice.

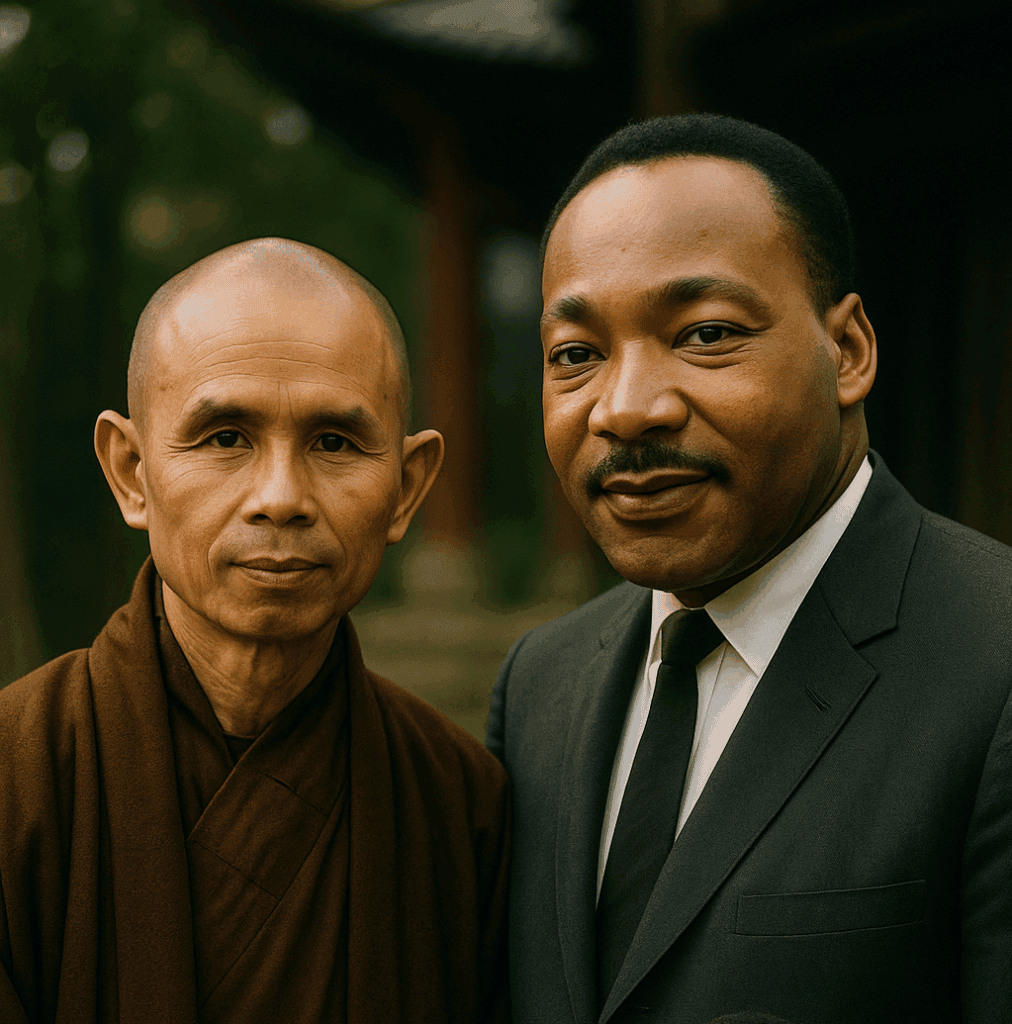

Thich Nhat Hanh and Engaged Buddhism in France

In the 1980s, Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh, exiled due to his peace activism during the Vietnam War, established Plum Village in southern France. This became one of the most influential Buddhist centers in Europe. Thich Nhat Hanh’s approach—deeply rooted in Vietnamese Zen and the concept of “engaged Buddhism”—emphasized mindfulness in daily life, ethical living, and compassionate action.

Plum Village became a model for lay practice, hosting thousands of international visitors annually, and his books and teachings had a profound impact on mindfulness and socially engaged spiritual life across the continent.

Zen and the Rise of European Dojos

Japanese Zen also gained strong traction in Europe after the war, especially through teachers such as Taisen Deshimaru, a Soto Zen monk who moved to France in 1967. He founded the Association Zen Internationale and numerous dojos, including a monastic training center at La Gendronnière.

His emphasis on rigorous zazen (seated meditation) attracted both spiritual seekers and existentially inclined Europeans. Other Japanese Zen teachers, such as Shunryu Suzuki’s successors, made similar inroads in Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands.

The Friends of the Western Buddhist Order (FWBO)

Founded in London in 1967 by Sangharakshita (Dennis Lingwood), the FWBO—now known as the Triratna Buddhist Community—was one of the first attempts to create a distinctly Western form of Buddhism.

Drawing on Theravāda, Mahāyāna, and Vajrayāna traditions, it emphasized lay commitment, ethical development, and artistic expression. While later controversies clouded its legacy, the FWBO played a key role in establishing a European-born sangha that did not rely on Asian cultural frameworks.

Theravāda Monasticism in the West

In the UK, Theravāda Buddhism became more visible through the work of Ajahn Chah’s Western disciples. Ajahn Sumedho, an American-born monk, founded Amaravati Monastery and other branch monasteries under the Thai Forest Tradition.

These institutions offered monastic training and lay retreats, emphasizing meditation, Vinaya (discipline), and mindfulness in daily life. Their success inspired the spread of Theravāda temples and meditation centers across the UK and continental Europe.

Secular and Psychological Adaptations

By the late 20th century, Buddhism in Europe also began evolving into secular and therapeutic forms. The rise of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), pioneered by Jon Kabat-Zinn in the U.S., found eager audiences in Europe’s health and education sectors. Teachers like Stephen Batchelor, who advocated for a secular, agnostic approach to Buddhist philosophy, helped frame Buddhism as a practical life philosophy compatible with science and humanism.

The post-war period marked a turning point for Buddhism in Europe, transforming it from a scholarly curiosity or immigrant faith into a living, multifaceted spiritual tradition. While still a minority religion, it now comprises a wide spectrum of institutions—from traditional monasteries to mindfulness schools—and continues to shape Europe’s spiritual and cultural landscape.

Modern Practice and Institutional Presence: Today, Buddhism in Europe includes both immigrant and convert communities. Notable traditions represented include Theravāda (especially in the UK and Italy), Zen (France, Germany), Tibetan Vajrayāna (especially popular in Switzerland, the UK, and Scandinavia), and secular mindfulness-based practices derived from Buddhist meditation.

While Buddhism remains a minority religion in Europe, its philosophical and meditative practices have significantly influenced European thought, psychology, and secular spirituality.

The Spread of Buddhism in Africa

Compared to Asia, Europe, or the Americas, the spread of Buddhism in Africa has been relatively modest and recent. Nonetheless, the tradition has established a visible and growing presence across parts of the continent, shaped by immigration, transnational networks, and local engagement. From cosmopolitan centers to rural retreat spaces, Buddhism in Africa reflects both global movements and regional particularities.

Colonial-Era Awareness and Early Contact

Although Buddhist ideas were known to European colonial administrators and missionaries stationed in Africa, there is no evidence of active Buddhist communities on the continent during the colonial period. Buddhism was generally viewed through orientalist or comparative religious lenses, studied more as an academic curiosity than practiced as a faith. It was only in the mid-20th century that actual Buddhist presence began to take root.

Asian Diaspora and the Foundation of Temples

The most significant factor in Buddhism’s arrival in Africa has been Asian immigration, particularly to eastern and southern Africa. In countries like South Africa, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, and Mauritius, communities of Chinese, Thai, Burmese, Sri Lankan, and Indian origin established small temples and centers to serve immigrant populations. These often focused on Theravāda or Mahāyāna traditions, and served both religious and cultural functions.

In South Africa, where the largest and most diverse Buddhist communities have developed, Chinese Mahāyāna and Sri Lankan Theravāda temples were among the first to be founded. Today, cities like Johannesburg, Durban, and Cape Town host temples, meditation centers, and interfaith dialogues with Christian, Hindu, and Muslim communities.

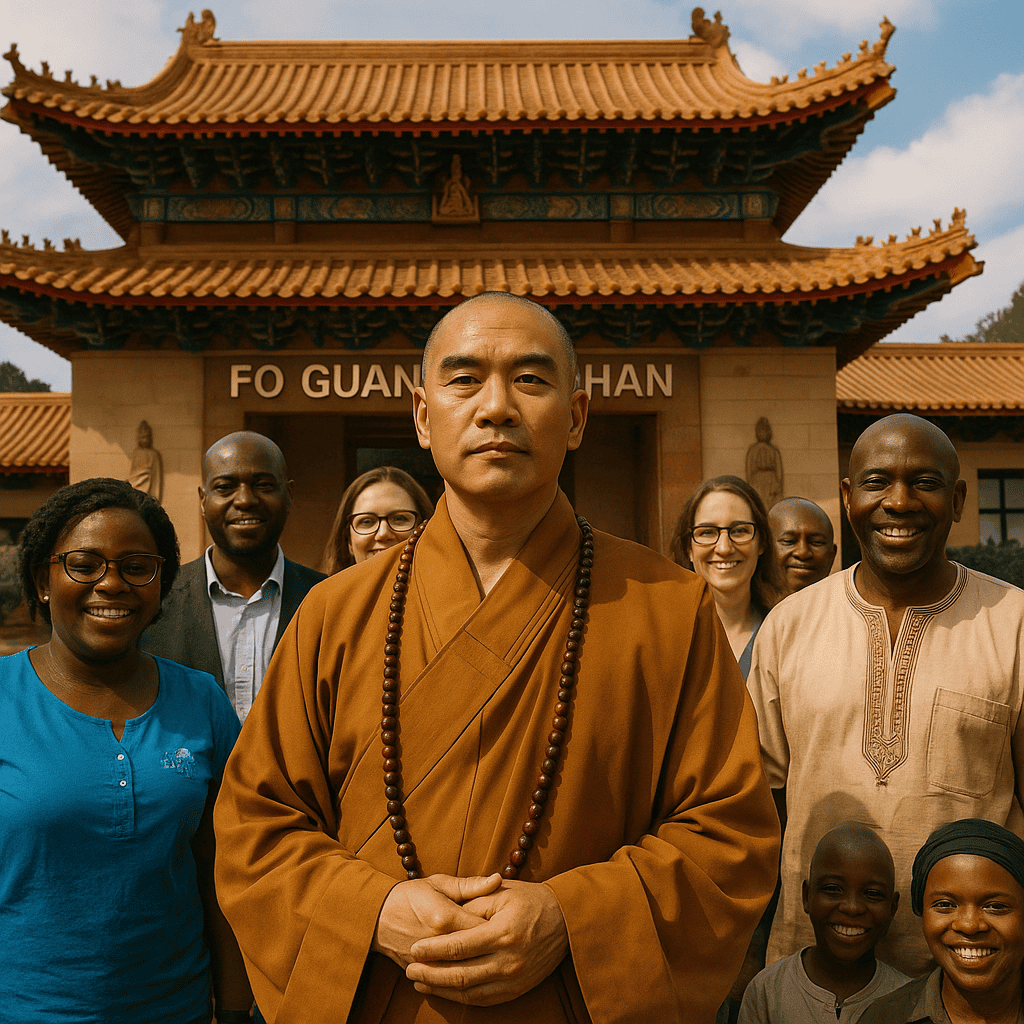

The Fo Guang Shan Movement

One of the most visible institutional presences in Africa has come from the Taiwanese Humanistic Buddhist organization Fo Guang Shan. They have established temples and outreach centers in countries such as South Africa, Malawi, and Botswana. Their approach emphasizes education, social service, and cultural activities, helping integrate Buddhism into civic life while promoting interreligious cooperation.

Convert Communities and Meditation Centers

Since the 1990s, a small but growing number of Africans have converted to Buddhism, especially through meditation-based approaches. Vipassanā centers following the lineage of S.N. Goenka have hosted silent retreats in South Africa and Kenya, attracting diverse participants. Western-trained teachers and African practitioners have begun offering local Dharma talks, often framed in secular or interfaith terms to resonate with broader audiences.

Social Engagement and Interfaith Work

In some African contexts, Buddhism has taken on a socially engaged form, addressing issues such as poverty, education, gender equality, and trauma recovery. Buddhist communities have participated in interfaith peacebuilding efforts in post-apartheid South Africa and have supported refugee aid and mindfulness programs for youth.

Challenges and Opportunities

Buddhism in Africa remains a minority religion, often overshadowed by Christianity, Islam, and indigenous traditions. It faces challenges of language, accessibility, and cultural resonance. However, the universal appeal of mindfulness, compassion, and nonviolence has created opportunities for dialogue and growth.

As African societies navigate rapid modernization, ecological concerns, and interreligious tensions, Buddhism’s emphasis on inner transformation and ethical living may find increasing relevance.

The Spread of Buddhism in the Americas

The transmission of Buddhism to the Americas, like in Europe, followed a dual path: first through Asian immigrant communities and later through Western converts inspired by its philosophy, meditation practices, and ethical values. Over the 20th century, the Americas became home to a wide array of Buddhist traditions, adapting dynamically to diverse social and cultural landscapes.

Early Asian Immigration and the Foundation of Temples

The first significant wave of Buddhism in the Americas came with the immigration of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean laborers in the 19th century. Many settled on the western coast of North and South America, especially in the United States, Canada, Peru, and Brazil.

In the U.S., Japanese immigrants established some of the first Buddhist temples, particularly Jōdo Shinshū (Pure Land) communities, in California and Hawaii. The Buddhist Churches of America, founded in 1899, served as both religious and cultural institutions for Japanese Americans. Similar Chinese and Japanese Buddhist temples appeared in Lima, Peru, and São Paulo, Brazil, often blending Mahāyāna practices with ancestral veneration and community support.

Zen, Beat Poets, and Countercultural Appeal

In the mid-20th century, Buddhism began attracting non-Asian converts, particularly through the influence of Zen. Japanese teachers such as D.T. Suzuki, Shunryu Suzuki, and Philip Kapleau introduced Zen philosophy and meditation to a generation of Western readers and seekers.

In North America, the Beat poets—figures like Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac—popularized Zen themes in literature and culture, presenting it as an alternative to materialism and institutional religion. The 1960s and 70s counterculture movements, particularly in California and New York, embraced Buddhism as part of a broader search for spiritual authenticity, simplicity, and ecological awareness.

Tibetan Buddhism and the Dalai Lama’s Influence

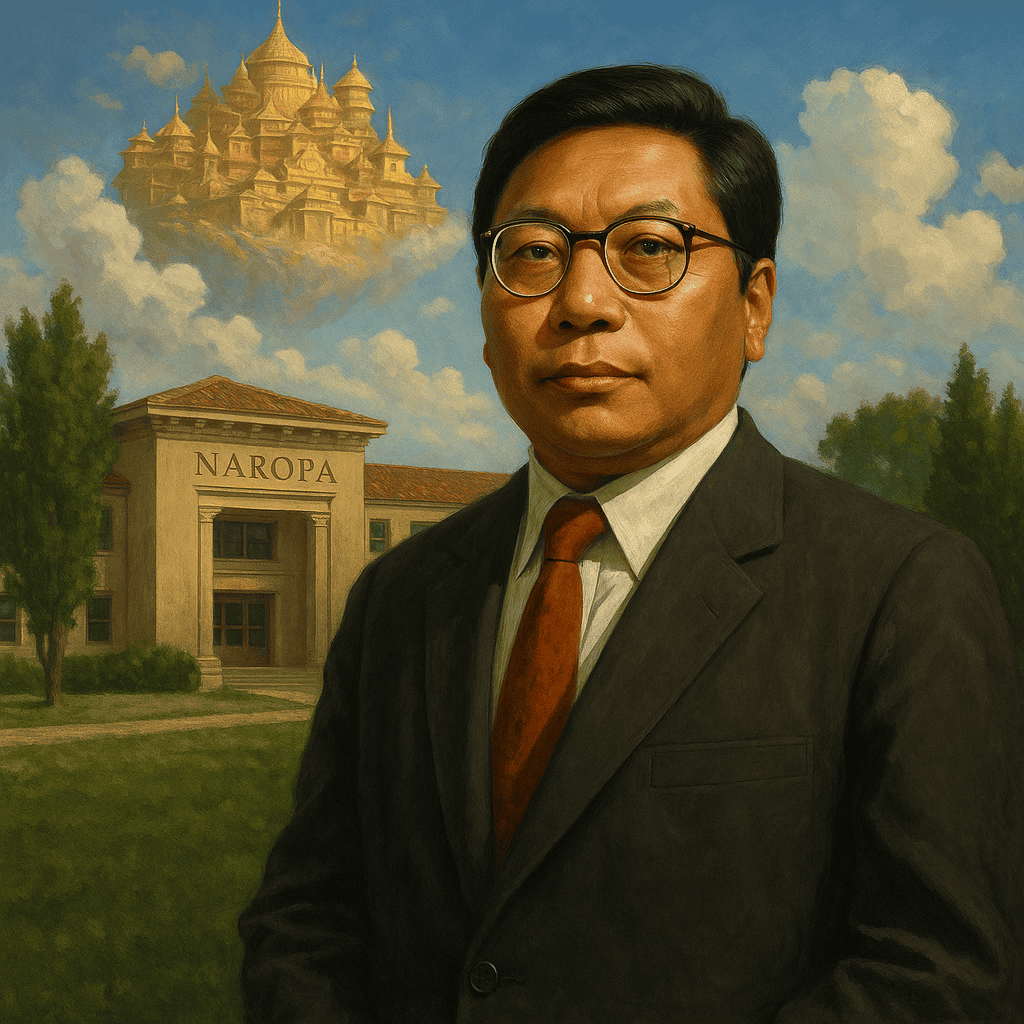

The Tibetan diaspora after 1959 led to the spread of Vajrayāna Buddhism across the Americas. The Dalai Lama’s visits, teachings, and Nobel Peace Prize in 1989 significantly raised the global profile of Tibetan Buddhism.

Teachers such as Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, who founded Naropa University in Colorado, and other Tibetan lamas established retreat centers and sanghas in the U.S., Canada, and parts of Latin America. Organizations like FPMT, Rigpa, and the Nyingma and Karma Kagyu networks developed devoted followings among Westerners.

Theravāda in the West

Theravāda Buddhism, particularly through the Thai Forest Tradition, also found a foothold in the Americas. Monasteries such as Abhayagiri in California and centers associated with Ajahn Chah’s lineage offer residential training for monastics and laypeople. Vipassanā meditation, especially the tradition of S.N. Goenka, spread rapidly across North and South America via ten-day silent retreats and a focus on universal, non-sectarian ethics and mindfulness.

Latin American Developments

In Latin America, Buddhism’s growth has been steady but less widespread. Brazil hosts large Japanese Buddhist communities, especially in São Paulo, alongside Zen, Tibetan, and modern mindfulness groups. Argentina, Chile, and Mexico have growing convert communities, often centered on meditation practice and Tibetan teachings. Language translation, interreligious dialogue, and cultural integration remain ongoing challenges.

Mindfulness and Secular Dharma

By the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the American embrace of mindfulness—as taught by Jon Kabat-Zinn and others—made Buddhist meditation accessible in secular, therapeutic contexts. Programs in hospitals, prisons, and schools brought Buddhist-derived practices into mainstream culture, often without explicit religious affiliation.

Diversity and Innovation

Buddhism in the Americas is now characterized by pluralism and innovation. It includes immigrant temples, convert sanghas, online communities, secular mindfulness programs, and socially engaged groups addressing race, ecology, trauma, and inequality. Teachers of color, women, and LGBTQ+ leaders are increasingly reshaping the narrative of what American Buddhism can be.

The Spread of Buddhism in Australia and Oceania

Buddhism arrived relatively late to Australia and Oceania, but it has grown steadily since the mid-20th century, becoming one of the most prominent non-Christian religions in the region. Shaped by patterns of immigration, global Buddhist networks, and a growing interest in meditation and mindfulness, Buddhism in Australia and neighboring Pacific countries reflects both traditional continuity and modern adaptation.

Early Contacts and Immigration

Buddhist contact with Australia began in the 19th century with Chinese laborers who arrived during the gold rush era of the 1850s. Though most were eventually repatriated or assimilated, they left traces of Buddhist belief and practice in rural areas and among early immigrant communities.

A more enduring Buddhist presence began to emerge in the mid-20th century with post-war migration from Southeast Asia and Sri Lanka. Later, refugees and immigrants from Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, China, and Tibet added to the growing diversity of Buddhist traditions represented across the continent.

Institutional Growth and Diversity

Today, Australia is home to a wide range of Buddhist traditions. Theravāda temples, especially those associated with Thai, Sri Lankan, and Burmese communities, are found throughout major cities. Vietnamese Mahāyāna temples are also prominent, serving large diaspora populations. Tibetan centers, particularly those connected to the Dalai Lama and organizations like FPMT, have flourished as well.

Multicultural urban centers such as Sydney and Melbourne now host temples, monasteries, and retreat centers from nearly every major Buddhist lineage. The Buddha’s Birthday is celebrated as a major cultural event in several cities, drawing interfaith and civic participation.

Convert Communities and Monastic Establishments

Australia has developed its own convert communities and institutions, often led by Western-born monks and lay teachers. A prominent example is Bodhinyana Monastery near Perth, founded by Ajahn Brahm, a British-born Theravāda monk in the Thai Forest Tradition. Known for his accessible teachings and advocacy for bhikkhunī ordination (female monastics), Ajahn Brahm has gained a global following.

Zen groups, Insight Meditation circles, and secular mindfulness communities also thrive across the country. Lay-led organizations like the Buddhist Council of New South Wales and the Buddhist Society of Victoria coordinate events, education, and dialogue between traditions.

Mindfulness and Secular Integration

As elsewhere, Buddhist meditation practices have entered secular domains in Australia, especially through psychology, education, and healthcare. Mindfulness programs are integrated into schools and therapeutic settings, often inspired by Buddhist principles but presented in non-religious language. This has increased public familiarity with Buddhist ideas even among non-adherents.

Buddhism in Oceania

In the Pacific Islands, Buddhism has a far smaller footprint, limited largely to expatriate communities and a few scattered temples. Fiji has small Chinese and Japanese Buddhist communities, while New Zealand has experienced growth patterns similar to Australia, albeit on a smaller scale. In New Zealand, Buddhist temples, retreat centers, and interfaith dialogue initiatives are present in Auckland, Wellington, and Christchurch.

Challenges and Future Directions

While Buddhism continues to grow in Oceania, challenges include maintaining cultural relevance for second-generation migrants, translating teachings into local contexts, and overcoming geographic isolation. However, the region’s openness to multiculturalism, environmental concern, and interest in mental well-being make it fertile ground for future expansion.

Conclusion: A Global Dharma

From its humble beginnings under the Bodhi tree in ancient India, the teachings of the Buddha have traversed deserts, mountains, and oceans. Carried by merchants, monks, pilgrims, exiles, scholars, and seekers, Buddhism has taken root on every continent. It has adapted to countless languages, cultures, and historical circumstances, yet retained its core commitment to awakening, ethical conduct, and the alleviation of suffering.

What might Siddhartha Gautama have said, had he known that his teachings would one day be practiced by people in Africa, Europe, the Americas, and Oceania—long after his death and far beyond the borders of ancient Magadha?

He might have smiled, not with pride, but with compassion. For the Buddha did not seek fame or conquest; he walked away from a palace, not toward one. He taught for the benefit of beings, not the building of institutions.

His only ambition was that others realize for themselves the freedom from suffering that he had discovered. Whether that freedom was realized in a bamboo grove in Rajgir or a meditation hall in Rio de Janeiro would have mattered little—only that the Dharma was known, practiced, and lived.

The Buddha once said, “As the great ocean has one taste, the taste of salt, so too does my teaching have one taste: the taste of liberation.” Today, that taste is being discovered anew in classrooms in Cape Town, retreats in British Columbia, temples in Berlin, and mindfulness programs in Sydney.

Buddhism’s global journey is not a story of religious dominance, but of resilient relevance—a path that continues to unfold wherever there are people willing to sit still, breathe deeply, and turn inward with honest attention.

In a fragmented world facing ecological crisis, social unrest, and existential anxiety, the gentle revolution of the Dharma offers a counter-current: simplicity over consumption, awareness over distraction, and compassion over fear. If the Buddha were to walk among us today, he would likely remind us that the real miracle is not that his name is known across the Earth, but that anyone—anywhere—can realize the end of suffering through their own mind.

The spread of Buddhism across the globe is not the triumph of a religion, but the quiet flowering of a human possibility: the awakening of wisdom and compassion in the hearts of all beings.

From the Dhammapada, Verse 183

To avoid all evil,

To cultivate good,

To purify the mind—

This is the teaching of all Buddhas.