Table of Contents

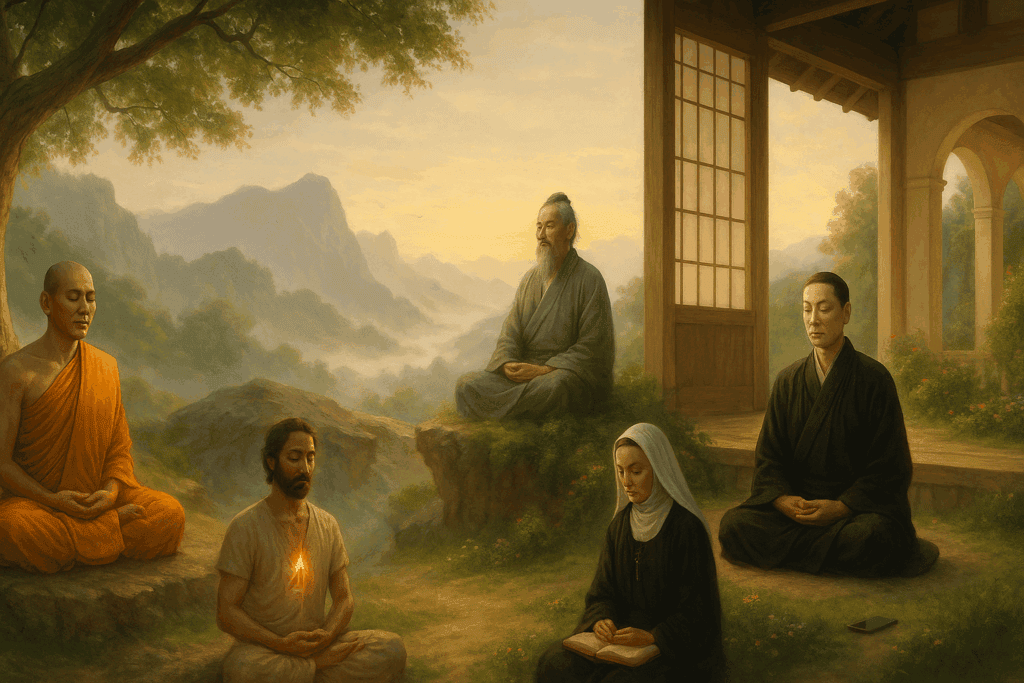

1. Introduction – The Many Paths to Stillness

Brief overview of the human pursuit of meditation across cultures and time, touching on its goals (calm, insight, transformation, healing).

2. Indian Yogic Traditions

- Pranayama – Breath regulation as meditative practice

- Dharana – Concentration on a single object

- Dhyana / Jhana – Sustained meditation leading toward absorption

- Samadhi – States of meditative absorption; interpreted in various ways

- Kundalini Meditation – Awakening and guiding inner energy

3. Buddhist Meditation Systems

Theravāda

- Samatha – Calm-abiding meditation

- Vipassanā – Insight meditation

- Ānāpānasati – Breath awareness as a complete path

Mahāyāna

- Visualization Practices (e.g., Pure Land, bodhisattva imagery)

- Mindfulness of Emptiness and Compassion

Vajrayāna (Tibetan)

- Deity Yoga – Visualization, mantra, mandala

- Mahamudra & Dzogchen – Direct awareness practices

Chan / Zen

- Zuòchán (Sitting Meditation) – Root of Zen practices

- Kōan Practice – Paradox and insight

- Zazen – Seated meditation

- Shikantaza – “Just sitting” with open awareness

4. Daoist Meditation

- Daoist Inner Alchemy – Breathing, visualization, and refinement

- Qìgōng – Moving and still meditations to harmonize qi

5. Western Traditions

Jewish Kabbalistic Meditation

- Prayer, sacred letter contemplation, ecstatic practices

Christian Contemplative Prayer

- Lectio Divina – Sacred reading and absorption

- Hesychasm – Eastern Christian repetition of the Jesus Prayer

6. Scientific and Psychological Methods

- Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR)

- Cognitive-Based Compassion Training

- Transcendental Meditation (TM) – Repetition of mantra

- Jungian Active Imagination – Dialogue with the unconscious

- Mind Palace / Memory Journey – Cognitive focus-based visualization

- Visualization Therapy – Guided mental imagery for healing

7. Classification of Techniques

- By Object (breath, mantra, visual image, emotion)

- By Goal (calm, insight, transformation, healing)

- By Posture (sitting, walking, lying, moving)

8. Conclusion – Unity in Diversity

Reaffirm the global importance of meditation and its adaptability to secular, spiritual, scientific, and cultural contexts.

1. Introduction – The Many Paths to Stillness

Across history and geography, human beings have sought a way to still the mind, open the heart, and transcend the churning of everyday thought. Meditation—in its countless forms—has served as a bridge between the ordinary and the extraordinary, between the self and the world, between silence and insight.

Though its outer expressions may differ, meditation is universally concerned with attention. Whether resting gently on the breath, visualizing a divine form, chanting a sacred phrase, or sitting silently in pure awareness, the practitioner trains the mind to settle, observe, transform, or awaken.

Some traditions focus on calming the mind (as in samatha or breath awareness), while others emphasize gaining insight into reality (as in vipassana, koan introspection, or contemplative prayer). Others still use meditation as a method for healing, energy cultivation, or even union with the divine.

This survey presents a panoramic view of the world’s meditative traditions, from the structured stillness of yogic and Buddhist methods to the mystical imagery of Jewish Kabbalah and Christian Lectio Divina; from Daoist alchemical visualizations to the scientific protocols of modern mindfulness-based therapy. Though diverse in method and intent, these practices all aim—whether implicitly or explicitly—at a re-centering of the self and a more harmonious relationship with life.

Rather than advocate one method over another, this article honors the multiplicity of approaches and the deep wisdom of the cultures that shaped them. In doing so, we invite readers into a comparative understanding of meditation—not as a fixed tradition, but as a living, evolving practice of humanity’s search for stillness, clarity, and wholeness.

2. Indian Yogic Traditions

The Indian subcontinent has cultivated one of the oldest and most systematic traditions of meditation. Rooted in the Vedic and later Upanishadic scriptures, and systematized through yogic philosophy—especially the Yoga Sutras of Patañjali—Indian meditative practices aim to refine the mind, master the senses, and realize the union of individual consciousness (atman) with universal consciousness (brahman). These practices are foundational not only to Hindu spiritual systems but also deeply influenced Jainism, Buddhism, and even aspects of Sikhism.

2.1 Pranayama – Breath Regulation

Pranayama is the art of regulating and directing the breath (prana meaning life force, ayama meaning extension or control). Though often practiced as a preparatory stage for deeper meditation, certain forms of pranayama—such as alternate nostril breathing (nadi shodhana), breath retention (kumbhaka), and slow, mindful inhalation and exhalation—can themselves become meditative. The breath serves as a bridge between body and mind, grounding awareness in the present and calming the nervous system.

2.2 Dharana – Focused Concentration

Dharana, one of the eight limbs of yoga outlined by Patañjali, means “concentration” or “holding the mind steady.” In practice, it involves fixing attention on a single object—a candle flame, a mantra, an image, or even the breath. The purpose is to quiet the mind’s distractions and train it in one-pointedness. Dharana is the precursor to deeper meditative absorption.

2.3 Dhyana / Jhana – Meditative Absorption

Dhyana (Sanskrit) or Jhana (Pali) refers to the state of sustained meditative focus and flow where awareness becomes continuous and effortless. Unlike dharana, which is active concentration, dhyana is a receptive, unified awareness. It is described as a tranquil state where the subject-object distinction begins to dissolve, allowing for deep inner peace and clarity.

2.4 Samadhi – Absorption or Enlightened Union

Samadhi is both the culmination of meditative effort and the transformative state it reveals. It is variously described as complete absorption in the object of meditation, a transcendent state of consciousness, or the realization of oneness with the divine or true self. In different schools of Indian philosophy, samadhi may refer to temporary meditative absorption (savikalpa) or final liberation (nirvikalpa samadhi), where all distinctions vanish and pure awareness remains.

2.5 Kundalini Meditation – Awakening Inner Energy

Kundalini meditation refers to the yogic process of awakening the latent spiritual energy (kundalini shakti) said to reside at the base of the spine. Through breathwork, visualization, mantra, and postural alignment, this energy is guided upward through the chakras—psychic energy centers—toward the crown of the head. The experience of awakened kundalini is described as transformative, purifying, and potentially overwhelming, thus traditionally requiring guidance from a qualified teacher.

3. Buddhist Meditation Systems

Buddhism has developed one of the most diverse and influential families of meditative practices in the world. Though rooted in the teachings of the historical Buddha (Siddhartha Gautama) in 5th-century BCE India, Buddhist meditation has evolved into distinct systems across Theravāda, Mahāyāna, and Vajrayāna traditions. At their core, these practices aim to overcome suffering through the cultivation of calm, insight, compassion, and awakening.

3.1 Theravāda Meditation

3.1.1 Samatha – Calm Abiding

Samatha means “calm” or “tranquility.” This form of meditation is used to still the mind by focusing on a single object—commonly the breath, a colored disk (kasina), or a repetition. The goal is to cultivate mental stability and absorption (jhana) as a foundation for insight. It is often considered a preliminary or supportive practice for deeper understanding.

3.1.2 Vipassanā – Insight Meditation

Vipassanā means “clear seeing” or “insight.” It aims to penetrate the true nature of phenomena—namely, their impermanence (anicca), unsatisfactoriness (dukkha), and non-self (anatta). Practitioners may observe body sensations, thoughts, emotions, or processes with open awareness and detachment, thereby unraveling conditioned patterns and deepening wisdom.

3.1.3 Ānāpānasati – Mindfulness of Breathing

Ānāpānasati (“inhalation and exhalation awareness”) is a complete and central practice in Theravāda Buddhism. Outlined in the Ānāpānasati Sutta, it guides practitioners through sixteen stages of breath-based contemplation, developing both samatha and vipassanā. According to tradition, the Buddha himself attained enlightenment through this method. Some lineages, like that of Webu Sayadaw, maintain that full awakening is accessible through this practice alone.

3.2 Mahāyāna Meditation

In the Mahāyāna traditions of China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, meditation is expanded beyond individual liberation to include the bodhisattva vow of universal compassion.

3.2.1 Visualization and Devotional Practices

Practitioners may visualize Buddhas or bodhisattvas—such as Amitābha or Avalokiteśvara—with great detail, often accompanied by mantra chanting and vows. Pure Land Buddhism, for instance, focuses on visualizing the Western Paradise and calling upon Amitābha’s name with faith and concentration.

3.2.2 Mindfulness of Emptiness and Compassion

Mahāyāna emphasizes the realization of śūnyatā (emptiness) and bodhicitta (the heart of awakening). Meditative analysis deconstructs phenomena to reveal their lack of inherent existence, while loving-kindness (maitrī) and compassion (karuṇā) are cultivated toward all beings.

3.3 Vajrayāna (Tibetan) Meditation

Tibetan Buddhism fuses Mahāyāna principles with ritual, symbolism, and esoteric transmission, creating a rich tapestry of meditative methods.

3.3.1 Deity Yoga

This core practice involves visualizing oneself as a deity (such as Tara or Vajrasattva), reciting associated mantras, and dissolving the visualization into emptiness. The aim is to embody awakened qualities and purify obscurations.

3.3.2 Mahāmudrā and Dzogchen

These advanced practices point directly to the nature of mind. In Mahāmudrā (Great Seal) and Dzogchen (Great Perfection), the practitioner rests in open awareness, recognizing the luminous, empty nature of all experience without manipulation.

3.4 Chan and Zen Meditation

Zen (Japanese) and its root tradition, Chan (Chinese), evolved as unique expressions of Mahāyāna Buddhism, emphasizing direct experience over conceptual knowledge.

3.4.1 Zuòchán – Seated Meditation

In Chan, zuòchán (“sitting meditation”) refers to the central practice of stillness and inquiry. While early Chan incorporated both samatha and vipassanā, it later moved toward more iconoclastic and non-conceptual methods.

3.4.2 Kōan Practice

A kōan is a paradoxical anecdote or question used to exhaust rational thought and provoke awakening. Practitioners meditate on a kōan—such as “What is the sound of one hand clapping?”—not to answer it, but to break through habitual patterns of mind.

3.4.3 Zazen – Seated Meditation

In Japanese Zen, zazen is simply “seated meditation.” In Rinzai Zen, it may include kōan introspection, while in Soto Zen, it centers on shikantaza.

3.4.4 Shikantaza – Just Sitting

Unique to Soto Zen, shikantaza means “nothing but sitting.” There is no object, no analysis—just open presence. One sits with total acceptance of each moment, embodying the path without seeking gain.

4. Daoist Meditation

Daoist meditation arises from ancient Chinese spiritual traditions that value harmony with nature, spontaneity, longevity, and inner transformation. While often less systematized than Buddhist or yogic methods, Daoist meditation is deeply rooted in observation of natural processes—breath, energy, and the flow of Dao (the Way). These practices range from gentle breathing exercises to complex alchemical visualizations aimed at spiritual immortality.

4.1 Stillness and Natural Awareness

At the heart of Daoist meditation is zuòwàng (“sitting and forgetting”), a form of contemplative stillness described in the Zhuangzi. This non-striving approach dissolves attachments and ego boundaries, allowing the practitioner to merge effortlessly with the Dao. It is a kind of spiritual wu-wei—actionless action—where no particular technique is used beyond resting in alert, receptive presence.

4.2 Inner Alchemy – Neidan

Inner Alchemy (neidan) is a sophisticated Daoist system of meditation involving breath control, visualization, and energetic transformation. Practitioners metaphorically “refine” their internal elements (jing – essence, qi – energy, shen – spirit) in a staged process designed to transmute mortal consciousness into immortal awareness.

This process includes:

- Breath cultivation (qi breathing) to regulate life force

- Visualizations of internal organs, energy channels, and elixir fields (dantians)

- Circulation of energy through the microcosmic orbit (governing and conception vessels)

- Fusion practices, where opposites (yin and yang, sun and moon) are united into an inner “golden pill” (jindan)

Though metaphorical, these alchemical practices are meant to guide both body and consciousness into refined integration, promoting health, clarity, and spiritual awakening.

4.3 Qìgōng – Moving and Seated Energy Practices

Qigong (qi – life force, gong – cultivation) combines physical posture, breath control, and mental intention into flowing or static meditative movements. While often practiced for health and balance, qigong can also serve spiritual aims by enhancing awareness of inner energy and synchronizing body-mind-spirit.

Some traditions distinguish between:

- Medical Qigong (for physical healing)

- Martial Qigong (to enhance stamina and power)

- Spiritual Qigong (to align with Daoist cosmology and inner alchemy)

In all forms, the key principle is song—relaxed alertness that allows energy to circulate freely and naturally.

5. Western Traditions

Although often overshadowed by the Eastern systems in contemporary meditation discourse, the West too has nurtured profound meditative traditions—especially within Jewish mysticism and Christian monasticism. These practices tend to emphasize contemplation, inner stillness, prayerful union with the divine, and reflection on sacred texts. While the language may differ, their aims—insight, transformation, communion—resonate with global counterparts.

5.1 Jewish Meditation and Kabbalah

Jewish meditation spans from early prophetic vision to rabbinic contemplation and the mystical ecstasies of Kabbalah. At its core lies the desire to draw close to Ein Sof—the infinite divine source.

5.1.1 Contemplative Prayer and Silence

Traditional Jewish prayer (especially in Hasidic and Kabbalistic schools) includes moments of silent communion, breath awareness, and focused kavanah—intention or heart-focus—on each word spoken. The Shema, a central prayer, becomes a meditative mantra when uttered with presence.

5.1.2 Kabbalistic Visualization

In Kabbalistic meditation, practitioners may visualize the sefirot (divine emanations), Hebrew letters, sacred names of God, or the unfolding of divine light. Techniques can be intensely visual, symbolic, or ecstatic. Some methods use repeated intonation of divine names to alter consciousness and reach mystical states.

5.2 Christian Contemplative Traditions

Meditation in Christianity often centers on deepening the personal relationship with God through silence, scripture, and stillness. From the early Desert Fathers to modern contemplatives like Thomas Merton, Christian meditation emphasizes surrender, love, and the indwelling presence of the Holy Spirit.

5.2.1 Lectio Divina – Sacred Reading

Lectio Divina is a fourfold process of spiritual reading, reflection, prayer, and contemplation. Practitioners read a short passage of scripture slowly, reflect on its meaning, offer spontaneous prayer, and finally rest in silent communion beyond words. The aim is not study but intimacy—entering the living word of God.

5.2.2 Hesychasm – Prayer of the Heart

An Eastern Orthodox tradition, hesychasm involves the repetitive recitation of the “Jesus Prayer” (“Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me”) in sync with the breath. Over time, the prayer becomes internalized, fostering a continuous awareness of divine presence. It is both method and mysticism, reaching toward union with the uncreated light.

Excellent addition. Here is a new subsection for your article, proportionally aligned with the other parts of Section 5:

5.3 Sufi Meditation

In the Islamic mystical tradition of Sufism, meditation takes the form of murāqabah—a term meaning “watchfulness” or “vigilant observation.” It refers to a quiet, inward state of presence in which the practitioner becomes aware of God’s gaze and dwells in remembrance (dhikr). Rather than clearing the mind of thought, murāqabah centers on deepening one’s awareness of divine presence, often with the intention of spiritual purification and nearness to the Beloved.

5.3.1 Dhikr – Remembrance of God

At the heart of Sufi practice is dhikr—the repetition of divine names or sacred phrases, either silently or aloud. These phrases—such as Lā ilāha illā Allāh (“There is no god but God”) or simply Allāh—are recited rhythmically, with the breath, often coordinated with subtle movements or music. Dhikr can be practiced alone or communally, with many Sufi orders incorporating chanting, drumming, and ecstatic dance (samāʿ) to elevate the soul.

5.3.2 Murāqabah – Watching the Heart

Beyond vocal dhikr, murāqabah involves resting inwardly in stillness and openness to God’s presence. Eyes may be closed, and attention gently anchored in the heart or in the center of the forehead. Advanced stages of murāqabah include awareness of divine attributes (Asmaʾ al-Ḥusnā), visions, and deep states of union (fanāʾ) and subsistence (baqāʾ) in God.

5.3.3 Love and Union

Unlike traditions that emphasize emptiness or detachment, Sufi meditation is infused with the language of love. The seeker is a lover, and meditation is the quiet listening for the Beloved’s whisper. The poetry of Rumi, Hafiz, and Ibn ʿArabī reflects this path of burning longing, surrender, and intimate nearness—often described not through abstract philosophy but the heart’s own yearning.

6. Scientific and Psychological Methods

In the modern era, meditation has increasingly moved into secular spaces—clinical psychology, neuroscience, education, and workplace wellness—through the lens of science and therapy. These approaches are often stripped of religious symbolism and focus instead on measurable benefits: reduced stress, improved focus, emotional regulation, and overall well-being. Yet many retain the core meditative aim—training attention and transforming consciousness.

6.1 Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR)

Developed by Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn in the 1970s, MBSR is an eight-week secular program grounded in Buddhist mindfulness, but framed in clinical, non-religious language. Participants learn to observe thoughts, feelings, and sensations without judgment—especially through body scan meditations, walking meditation, and breath awareness. It has become a gold standard in stress management and is widely studied in scientific literature.

6.2 Cognitive-Based Compassion Training (CBCT)

Emerging from both contemplative traditions and cognitive science, CBCT focuses on intentionally cultivating compassion toward self and others. It includes guided reflections on common humanity, empathetic visualization, and mental exercises that challenge unhelpful cognitive patterns. The method is especially relevant in healthcare, education, and trauma recovery.

6.3 Transcendental Meditation (TM)

Popularized in the West by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in the mid-20th century, TM involves silently repeating a personalized mantra for 15–20 minutes twice a day. TM emphasizes effortlessness—allowing the mind to settle inward naturally. Numerous studies claim benefits ranging from reduced anxiety to improved cardiovascular health. Prominent advocates include David Lynch and Jerry Seinfeld.

6.4 Jungian Active Imagination

In Jungian psychology, meditation takes the form of active imagination, a process of entering into conscious dialogue with images and figures from the unconscious. Rather than silence or stillness, the practice engages imagination to explore inner conflicts and archetypes. It is meditative in its depth and introspective insight, bridging dreamwork and self-realization.

6.5 Mind Palace and Visualization Techniques

Based on ancient mnemonic practices (e.g. the Method of Loci), the Mind Palace technique involves mentally navigating an imagined space to encode and retrieve information. While often used for memory, it can become a deeply meditative visualization practice—training focus, creativity, and spatial memory.

6.6 Guided Visualization and Somatic Imagery

Modern therapeutic methods often use guided visualization for healing—imagining light, warmth, or supportive figures entering the body to reduce pain or anxiety. These techniques overlap with hypnosis and body-based therapies, emphasizing embodiment, self-soothing, and nervous system regulation.

7. Classification of Techniques

Despite the wide diversity of global meditation practices, most techniques can be meaningfully classified according to their object of focus, intended outcome, and mode of practice. These categories offer helpful ways to understand the relationships—and distinctions—between traditions.

7.1 By Object of Meditation

Different practices involve attention to different focal points:

- Breath – e.g., Ānāpānasati, Pranayama

- Mantra or Sound – e.g., Transcendental Meditation, Hesychasm, Vedic japa

- Visual Image – e.g., Tibetan deity yoga, Christian icons, Kabbalistic sefirot

- Thought or Phrase – e.g., Lectio Divina, kōan introspection

- Sensations – e.g., Vipassanā body scan, Zen awareness of posture

- Void or Formlessness – e.g., Shikantaza, Dzogchen, “just sitting” practices

- Movement – e.g., Qigong, walking meditation, mindful dance

7.2 By Goal or Function

While all meditation involves the cultivation of awareness, practices may differ in intent:

- Calm and Relaxation – e.g., Samatha, MBSR, breath-based practices

- Insight and Wisdom – e.g., Vipassanā, Mahāmudrā, Kabbalistic reflection

- Union or Communion – e.g., Samadhi, Lectio Divina, Bhakti meditation

- Healing and Integration – e.g., Guided visualization, Jungian techniques

- Energy Cultivation – e.g., Kundalini yoga, Daoist internal alchemy

- Ethical Transformation – e.g., Metta meditation, compassion training

7.3 By Mode or Posture

Posture is not just physical—it shapes the atmosphere and accessibility of the practice:

- Seated Stillness – the most common form (zazen, yogic dhyana)

- Lying Down – often used for body scans, sleep meditations, or guided practices

- Walking Meditation – practiced in many traditions (Zen, Theravāda, mindfulness)

- Movement-Based – Qigong, mindful yoga, spontaneous or ritual motion

- Eyes Open vs. Eyes Closed – varies by tradition and cognitive emphasis

- Guided vs. Unguided – instructor-led, app-based, or self-initiated

This classification is not rigid. Many practices blend types—such as a visualization used to generate compassion, or a breath-based technique leading to insight. Yet understanding these dimensions helps practitioners and scholars navigate the field more skillfully.

8. Conclusion – Unity in Diversity

From the mountain caves of Tibet to the silent pews of Christian monasteries, from Daoist hermit huts to hospital mindfulness programs, meditation continues to reveal itself as a universal language of inner transformation. Though the techniques differ—breath, mantra, stillness, movement—the underlying intention remains deeply human: to quiet the turbulence of the mind, to glimpse truth, to soften the heart, to heal the soul.

We have surveyed the rich panorama of global meditative practices: the disciplined ascent of yogic dhyana, the insight-seeking of Vipassanā, the open wonder of Zen, the alchemical elegance of Daoist inner refinement, the sacred intimacy of Lectio Divina, and the pragmatic clarity of modern mindfulness science. In each case, we encounter a different doorway into the same spacious interiority—the vast realm of consciousness itself.

Meditation is not the property of any one culture or religion; it is a human heritage, a shared art of being. Whether practiced as devotion, discipline, or therapy, it offers a mirror through which we may come to know ourselves and relate more harmoniously to others. In an age of distraction and fragmentation, meditation provides not escape but return—a return to presence, to clarity, to wholeness.

In honoring the diversity of meditative paths, we affirm the deeper unity of the contemplative impulse across traditions. Let each seeker find the method that resonates most truly—and follow it with patience, integrity, and care. For stillness is not the end of the path; it is the ground from which the path begins.