Inside Monastic Culture Series Part X

Contents

- Silent Temples, Living Traditions: The Story of Japanese Monasticism

- Japan: Land, People, and Early Religion

- The Introduction and Early Spread of Buddhism

- Buddhist Monasticism in the Nara and Heian Periods

- Feudal Era Zen and the Warrior Monastic Spirit

- The Great Schools of Japanese Buddhism

- Early Modern Period: Zen and Monastic Life in Edo Japan

- Monastic Architecture and Interiors: The Space of Awakening

- A Day in the Life of a Japanese Buddhist Monk or Nun

- The Meiji Restoration and the Modern Challenges to Japanese Monasticism

- Japanese Monasticism Today: Revival, Globalization, and Contemporary Practice

- Conclusion: The Living Tradition of Japanese Monasticism

Silent Temples, Living Traditions: The Story of Japanese Monasticism

Japanese monasticism is not simply a collection of ancient rituals or remote temples—it is a living tradition, a disciplined path that has shaped and reflected the spirit of Japan for over a thousand years. At its heart lies a deep reverence for nature, simplicity, and the relentless pursuit of awakening.

From the early worship of kami in sacred groves to the grand Buddhist monasteries modeled on Chinese prototypes, Japanese monastic life has evolved through waves of cultural influence, political upheaval, and creative renewal. It has produced warrior-monks and wandering poets, silent hermits and dynamic reformers, artists and teachers who left indelible marks on the world.

Today, even in a fast-changing and often restless society, the call of the monastic life endures. In the stillness of a Zen hall, in the seasonal rhythms of temple rituals, in the simple act of sitting upright and breathing deeply, the timeless spirit of Japanese monasticism continues to invite all who seek clarity, compassion, and freedom.

This article traces the journey of Japanese monasticism—from its earliest roots to its global flowering—revealing a tradition that, though ancient, remains vibrantly alive.

Japan: Land, People, and Early Religion

Japan is an island nation in East Asia, consisting of four main islands—Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, and Shikoku—and numerous smaller islands. Surrounded by the Pacific Ocean, Sea of Japan, and East China Sea, Japan’s geography of rugged mountains, forests, and coastlines has historically fostered both isolation and a deep reverence for nature.

Today, Japan is a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary government, known for its blend of ancient tradition and cutting-edge modernity. The Japanese society highly values community, discipline, and respect for heritage, qualities that trace back to its earliest spiritual roots.

In ancient times, the Japanese people worshiped kami—nature spirits and deified ancestors—through rituals of purification and offerings at sacred sites such as groves, mountains, waterfalls, and rock formations. This indigenous spirituality was later termed Shinto (“the Way of the Gods”). Shinto was not a codified religion but a system of practices centered on maintaining harmony between people, nature, and the divine.

The rulers of early Japan served as both political leaders and high priests, overseeing rituals that preserved the sacred order. Temples, or jinja, were simple shrines built to house kami, often situated in places of natural beauty. Purification rituals, seasonal festivals (matsuri), and offerings of food and music were central practices. Shinto emphasized purity, sincerity (makoto), and gratitude to the natural world.

By the sixth century CE, however, profound changes were on the horizon. Buddhism, carried by monks and diplomats from China and Korea, would soon introduce new religious ideals, art forms, and institutions to the Japanese archipelago.

The Introduction and Early Spread of Buddhism

Japan lies within the greater sphere of Chinese influence, along with Korea and Vietnam. As part of this civilizational network, Japan absorbed a wide array of Chinese cultural elements, from philosophy and religion to government, architecture, writing, music, and the arts.

According to the Book of Liang (written in 635 CE), five Buddhist monks from Gandhara—a region in present-day Pakistan and Afghanistan—traveled to Japan in 467 CE. They referred to Japan by the mythological name Fusang (扶桑), meaning a distant eastern land across the sea.

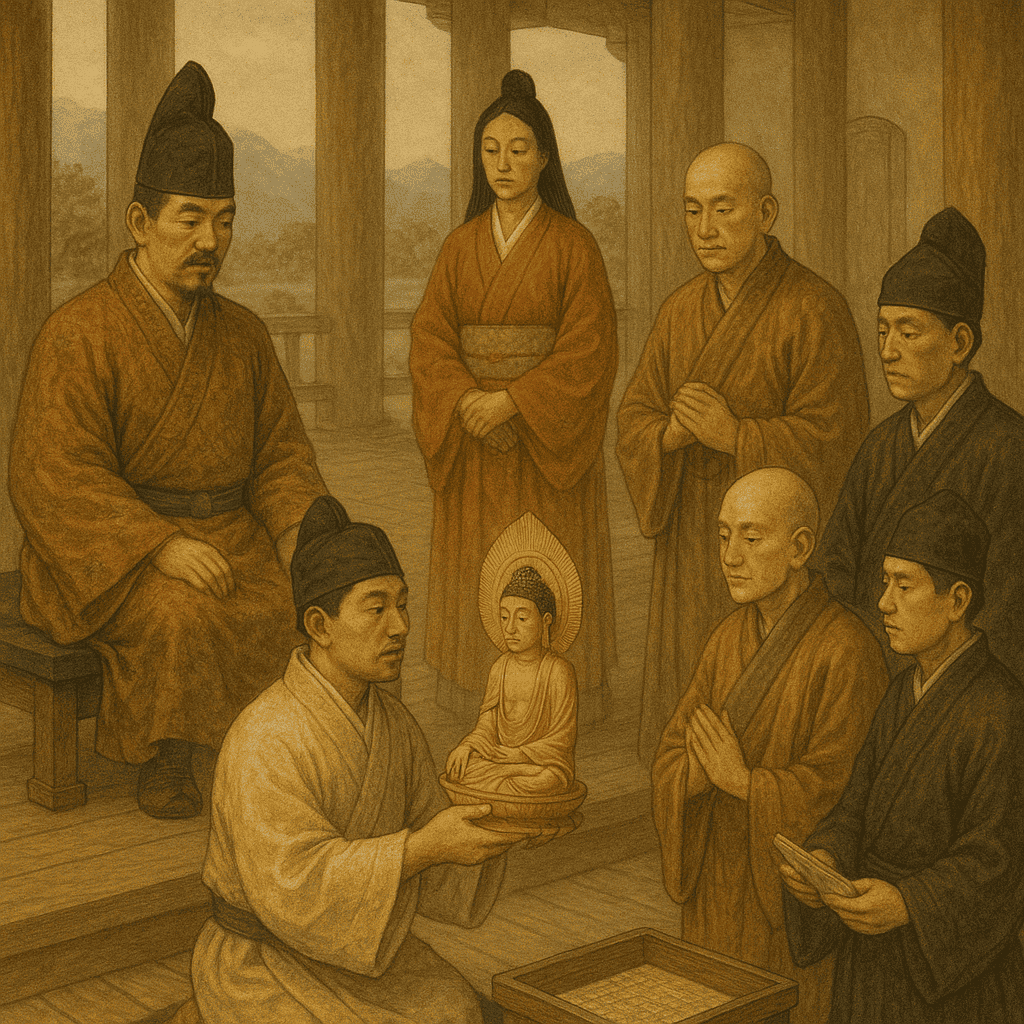

While some Buddhist contacts occurred earlier, the official introduction of Buddhism to Japan is recorded in the Nihon Shoki as occurring in 552 CE. At that time, King Seong of Baekje (in present-day Korea) sent a mission to Emperor Kinmei, offering an image of the Buddha, Buddhist sutras, and monks or nuns to propagate the new faith.

Initially, the adoption of Buddhism was gradual and met with some resistance. Native clans loyal to Shinto traditions hesitated to embrace foreign gods and practices. However, powerful aristocratic families like the Soga clan championed the new religion, seeing its potential to unify and legitimize state power. The Soga sponsored the construction of Japan’s first Buddhist temple, Hōkō-ji (later renamed Asuka-dera) between 588 and 596 CE, in the capital city of Asuka.

By 607 CE, Emperor Suiko, seeking deeper engagement with Chinese culture, dispatched an envoy to the Sui Dynasty of China to obtain Buddhist scriptures and deepen Japan’s knowledge of continental civilization. As Buddhist clergy increased in number, a formal hierarchy was established, with offices such as Sōjō (archbishop) and Sōzu (bishop). By 627 CE, Japan boasted 46 temples, 816 monks, and 569 nuns, laying the groundwork for a flourishing monastic culture.

Buddhist Monasticism in the Nara and Heian Periods

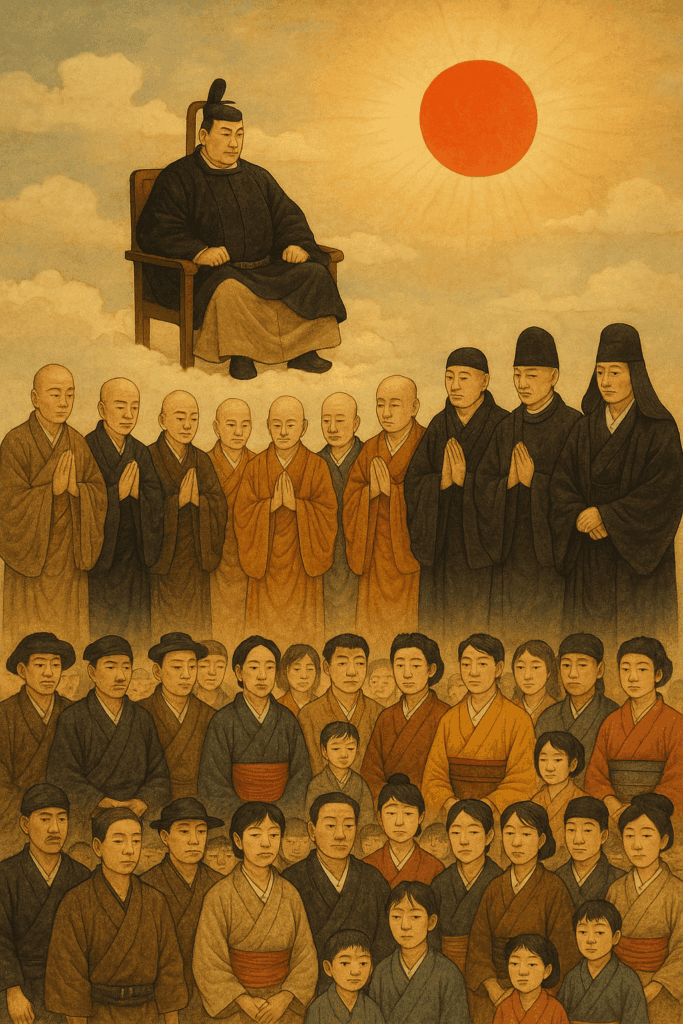

The Nara period (710–794 CE) marked the true institutionalization of Buddhism in Japan. The capital city of Nara (Heijō-kyō) was modeled after Chang’an, the grand capital of Tang China. Influenced by Chinese models, the Japanese imperial court embraced Buddhism both as a personal faith and as a tool of statecraft.

The Six Nara Sects (Nanto Rokushū), all originating from Chinese schools, took root around the ancient capitals of Asuka and Nara. These sects included Kegon, Hossō, Sanron, Jōjitsu, Ritsu, and Kusha, and although temples specialized in different teachings, many monks were trained in multiple traditions.

Grand temples such as Tōdai-ji were erected, becoming powerful religious and political centers. In 752 CE, the colossal Great Buddha (Daibutsu) of Nara was consecrated—a massive bronze image symbolizing both the spiritual aspirations and worldly might of the Japanese state.

During the late Nara period, a new and profound influence arrived: Esoteric Buddhism (mikkyō). Monks such as Kūkai (774–835), founder of the Shingon school, and Saichō (767–822), founder of the Tendai school, traveled to Tang China to study advanced teachings. Upon returning, they introduced ritual-based, mystical practices that emphasized mantras, mandalas, and complex rites intended to realize enlightenment in this very life.

The Heian period (794–1185 CE) saw the capital move to Kyoto, and monastic power continued to grow. Temples amassed vast landholdings and influence, sometimes even raising armies of sōhei (warrior-monks) to protect their interests. Buddhism and Shinto coexisted in a dynamic balance, a relationship sometimes described as shinbutsu-shūgō, or the syncretism of kami and Buddhas.

Through these developments, monastic institutions became the beating heart of medieval Japanese culture, producing scholars, artists, warriors, and mystics who shaped the nation’s destiny for centuries to come.

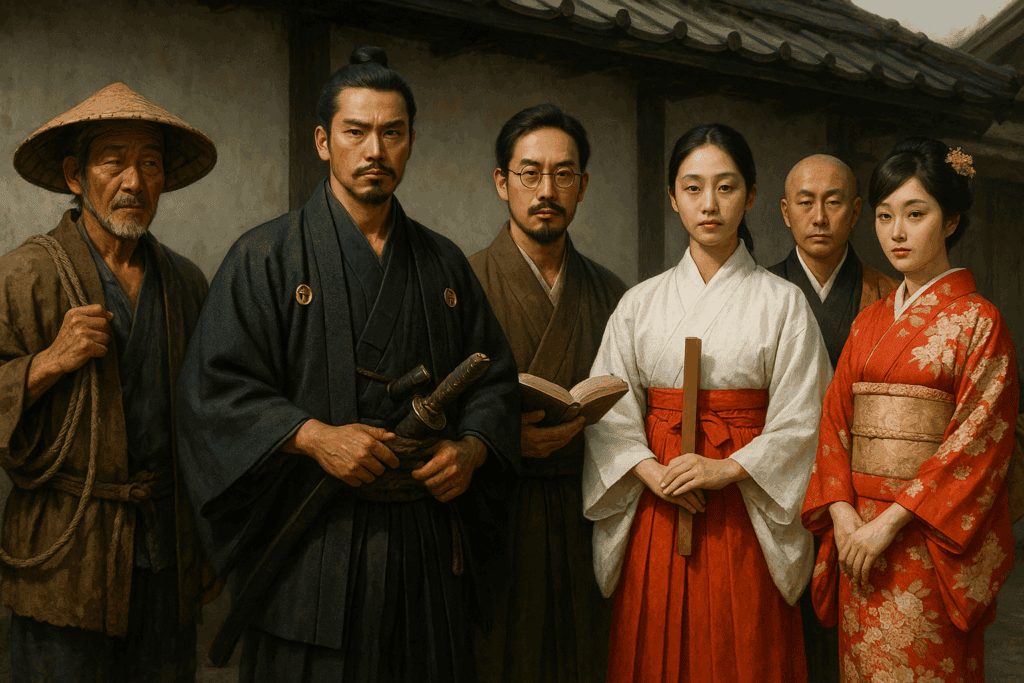

Feudal Era Zen and the Warrior Monastic Spirit

The feudal era of Japan, spanning from the twelfth century until the Meiji Restoration in the nineteenth, was an age when real power shifted from the emperor to the shogun, the military dictator. Over time, even the authority of the shogun was checked by the growing complexity of the samurai bureaucracy.

During this period, the samurai class, or bushi (armed gentry), developed a distinct way of life known as budō (“the martial way”) and refined an intricate system of martial arts, or bujutsu.

Samurai training emphasized both external and internal disciplines. Externally, samurai practiced unarmed combat and mastered a variety of weapons, including the bow, spear, staff, sword, and chain weapons. Internally, their training focused on cultivating mental clarity, emotional discipline, and spiritual resilience.

The Kamakura Period (1185–1333)

The Kamakura period marked a seismic shift in Japanese society, as the military class seized control from the imperial aristocracy. In 1185, the Kamakura shogunate was established, initiating an era when warrior values became dominant in political and cultural life.

This period also saw the introduction and flourishing of two Buddhist traditions that would have lasting impact:

- Pure Land Buddhism (Jōdo-shū), promoted by evangelists such as Genshin and articulated by monks like Hōnen, emphasized salvation through faith in Amitābha Buddha. It became—and remains—the largest Buddhist sect in Japan.

- Zen Buddhism, introduced by monks such as Eisai and Dōgen, emphasized direct insight through meditation (zazen) rather than doctrinal study. Zen was rapidly adopted by the samurai elite, whose ideals of simplicity, endurance, and direct action harmonized with Zen’s austere discipline.

Additionally, the influential monk Nichiren began teaching exclusive devotion to the Lotus Sutra, founding a school that emphasized religious activism and societal reform through faith. Nichiren Buddhism would leave a profound and enduring mark on Japanese religious and political life.

The samurai were deeply influenced by a fusion of spiritual and martial disciplines. Alongside the divinely inspired teachings of Shinto and Buddhism, they studied The Art of War by the Chinese strategist Sun Zi (Sun Tzu) and, later, the Book of Five Rings by the legendary swordsman Miyamoto Musashi (1584–1645). Although Musashi largely transcended sectarian affiliations, he was raised as a Zen Buddhist and continued to draw upon Zen insights throughout his life.

Zen, Martial Arts, and the Samurai Mind

At the heart of the samurai’s internal training was the practice of zazen (“seated meditation”). Warriors cultivated deep concentration, focusing on the hara, the center of gravity located in the lower abdomen, seen as the seat of both physical balance and ki (life energy, from the Chinese qi).

Zazen practices varied: they might begin with simple breath awareness, breath counting, or the even more profound method of shikantaza (“just sitting”). In some contexts, meditation sessions lasted mere minutes; in others, particularly during intensive retreats, they could extend for ten hours or more. Another Zen method embraced by the warrior elite was the kōan, enigmatic sayings or questions meant to break the logical mind and awaken sudden insight.

Zen principles came to permeate many aspects of Japanese culture. Beyond the battlefield, they expressed themselves in poetry, calligraphy, painting, the tea ceremony (chanoyu), garden design, and of course, the martial arts.

The Samurai, the Rōnin, and the Ninja

The samurai were trained to transcend fear and attachment to life, accepting death as a probable consequence of their duty. This stoic attitude led to the development of intricate rituals of seppuku (ritual suicide) for those who faced dishonor or defeat. Yet the warrior’s disdain for death often extended outward, creating harsh conditions for commoners. By law, a samurai could summarily execute any civilian who failed to show proper deference.

Disillusionment with the samurai’s arrogance grew over time. Many rōnin—masterless warriors—resented the rigid hierarchy and became wanderers, offering their martial skills for hire. These rōnin often trained farmers and peasants in the martial arts, enabling popular uprisings against oppressive rule. Ingenious peasant warriors fashioned improvised weapons from farm tools, creating new, deadly arts.

Meanwhile, lords employed clandestine networks of spies and assassins known as ninja. These shadow warriors perfected techniques of espionage, sabotage, and guerrilla warfare.

Another figure of the feudal landscape was the mountain ascetic, a hybrid of monk, magician, healer, and martial artist. Often practicing mikkyō (esoteric Buddhism), these hermit monks pursued enlightenment through rigorous disciplines and secret rituals. They were respected—even feared—as teachers of the martial arts, and many samurai sought them out to deepen their physical and spiritual prowess.

Martial expertise was guarded within ryū (schools), where methods and teachings were considered precious secrets, passed down from master (sensei) to disciple.

Warriors frequently traveled across provinces seeking challenges to test their skill and opportunities for instruction. Nowhere was this more evident than among the swordsmen, for the sword was not merely a weapon—it was a symbol of honor, soul, and spiritual path. Revered almost as a deity, the sword embodied the paradox of life and death within the warrior’s hand.

Shinto, Martial Arts, and Zen

Although Zen was influential, not all warriors were Zen adherents. Ancient Shinto shrines, such as Ise Jingū, Katori Jingū, and Kashima Jingū, remained sacred centers of spiritual life. Some martial traditions, like Katori Shintō-ryū, founded in the fifteenth century by Iizasa Chōisai Ienao (1387–1488), blended Shinto and esoteric Buddhist practices rather than Zen.

Unlike Zen monks, who often renounced wealth and social status, the families heading martial traditions like Katori retained worldly privileges, allowing them to preserve and transmit the complete martial systems of the samurai—including kendō (swordsmanship), judō (grappling), iaidō (sword-drawing), and ninjutsu (stealth arts).

The enduring legacy of Japan’s feudal monastic spirit was not confined to monasteries; it lived equally in the silent meditation hall, on the battlefield, and within the soul of the warrior walking the path of life and death.

The Great Schools of Japanese Buddhism

As Buddhism took root and evolved in Japan, it gradually diversified into a rich tapestry of sects and lineages. Historically, Japanese Buddhist institutions are grouped into major schools based on the period and style of their development: the scholastic schools of the Nara period, the esoteric traditions of the Heian period, and the dynamic new movements of the Kamakura period. Together, they laid the foundations for the thirteen official schools recognized in the pre-World War II period, with over fifty-six distinct branches.

The Six Schools of Nara Buddhism (710–794)

The Nara period witnessed the first major institutionalization of Buddhism under state patronage. Influenced by Korean and Chinese models, the Japanese government established six academic schools, known collectively as the Rokushū (六宗, “Six Sects”), centered around the capital city of Nara:

- Kusha-shū (倶舎宗): Focused on the analytical study of existence based on the Abhidharma-kosha.

- Jōjitsu-shū (成実宗): Concentrated on the “Establishment of Truth” doctrines, refining theories of emptiness.

- Sanron-shū (三論宗): The “Three Treatises” school, emphasizing Madhyamaka philosophy and the nature of reality as void.

- Ritsu-shū (律宗): A school dedicated to the strict interpretation and observance of the Vinaya (monastic precepts).

- Hossō-shū (法相宗): Rooted in Yogācāra philosophy, focusing on consciousness-only doctrines.

- Kegon-shū (華厳宗): Based on the Avataṃsaka Sūtra (Flower Garland Sutra), emphasizing the interpenetration of all phenomena.

These schools were closely tied to political power, and their growing influence eventually led Emperor Kanmu to relocate the capital to Heian-kyō (Kyoto), seeking to free the throne from the monastic elite’s control.

The Esoteric Schools of Heian Buddhism (794–1185)

Reacting to the scholasticism of Nara Buddhism, two new, more practice-centered schools emerged during the Heian period:

- Tendai (天台宗): Founded by Saichō (767–822) after studying the Tiantai tradition in China. Tendai emphasized the universality of Buddha-nature, the primacy of the Lotus Sutra, and incorporated Vajrayana (esoteric) rituals.

- Shingon (真言宗): Founded by Kūkai (774–835), who studied Tangmi (Chinese Esoteric Buddhism) under Master Huiguo in China. Shingon practice centers around mantras, mandalas, and mudras, using elaborate rituals to realize enlightenment in this life.

These schools brought a mystical dimension to Japanese Buddhism, merging devotionalism, ritual, and rigorous meditative practices. Shingon, in particular, remains one of the world’s few surviving Vajrayana traditions outside of Tibet.

By the twelfth century, the combined influence of the Nara, Tendai, and Shingon temples created a powerful religious aristocracy, leading to the next great shift: the Kamakura reformation.

The New Schools of Kamakura Buddhism (1185–1333)

The Kamakura period ushered in a revolutionary phase in Japanese religious life, often called Kamakura Buddhism. This era responded to widespread social unrest and disillusionment with the established monastic orders. The new movements were simpler, more accessible to common people, and often critical of the elaborate ritualism of earlier schools.

Three major streams of Kamakura Buddhism emerged:

Pure Land Schools (Amida Buddhism)

- Jōdo-shū (Pure Land School): Founded by Hōnen (1133–1212), it emphasized faith in Amida Buddha and recitation of the nembutsu (“Namu Amida Butsu”) as the sole path to rebirth in the Western Paradise.

- Jōdo Shinshū (True Pure Land School): Founded by Shinran (1173–1263), a disciple of Hōnen, it further simplified Pure Land practice, emphasizing absolute reliance on Amida’s grace.

Pure Land Buddhism became the most widespread form of Buddhism among the Japanese populace, offering hope of salvation to all regardless of social status or education.

Zen Schools

- Rinzai-shū (臨済宗): Introduced by Eisai (1141–1215) in 1191, Rinzai emphasized rigorous kōan practice—meditating on paradoxical statements to break through rational thinking—and emphasized disciplined monastic life.

- Sōtō-shū (曹洞宗): Introduced by Dōgen (1200–1253) in 1227 after studying in China, Sōtō emphasized shikantaza (“just sitting”), a form of silent illumination meditation.

- Ōbaku-shū (黄檗宗): A later Zen school, introduced in the seventeenth century by Chinese monks of the Linji tradition, blending Rinzai Zen with Pure Land practices and Chinese Ming dynasty culture.

Zen’s focus on direct experience, simplicity, and profound discipline resonated deeply with the samurai class and left a lasting impact on Japanese aesthetics, from ink painting to architecture to the tea ceremony.

Nichiren Buddhism

- Nichiren-shū (日蓮宗): Founded by Nichiren (1222–1282), it focused exclusively on devotion to the Lotus Sutra. Nichiren taught that chanting the title, Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, was the sole effective practice in the age of the Dharma’s decline (mappō).

Nichiren Buddhism distinguished itself with its social activism, confrontational stance toward other Buddhist schools, and vision of societal transformation through spiritual practice.

Early Modern Period: Zen and Monastic Life in Edo Japan (1600–1868)

The Edo period, also known as the Tokugawa period, was a time of unprecedented stability, economic growth, and cultural flourishing in Japan. After centuries of civil war and upheaval, the Tokugawa shogunate established strict control over the country, promoting social order through a rigid class hierarchy and a centralized feudal system. Religion, particularly Buddhism, was drawn into the machinery of governance, yet it also experienced significant internal development and cultural refinement.

Buddhism under Tokugawa Rule

In the early Edo period, Buddhism was formally enlisted as an instrument of state control. The Tokugawa government implemented the danka system, which required every family to register with a Buddhist temple. This registration served primarily as a means of suppressing Christianity, which the regime viewed as a threat to national unity. However, it also entrenched Buddhism’s role as a vital part of daily Japanese life.

Temples became administrative centers, responsible not only for religious rites but for population record-keeping and even local governance. Despite this bureaucratic role, temple life remained rich and vibrant, fostering ongoing developments in monastic practice, education, and the arts.

The Zen Renaissance

Although many Buddhist schools continued to thrive, it was Zen Buddhism, particularly the Rinzai and Sōtō schools, that most deeply influenced the cultural life of Edo Japan.

Rinzai Zen

The Rinzai school maintained its traditional emphasis on kōan practice and strict monastic discipline. It became especially popular among the samurai class, who valued its martial rigor, psychological training, and aesthetic sensibility. Rinzai monasteries produced some of the era’s most celebrated masters, such as Hakuin Ekaku (1686–1769), who revitalized Rinzai practice, systematized kōan training, and opened Zen to broader layers of society beyond the warrior elite.

Hakuin taught that enlightenment was accessible to all through intense meditation, rigorous self-examination, and sustained effort, democratizing what had often been an aristocratic path.

Sōtō Zen

The Sōtō school, emphasizing shikantaza (“just sitting”), appealed to a broader, more rural base. Sōtō temples were widespread throughout the countryside, ministering to farmers and villagers as well as training monastics. The simplicity of Sōtō practice, its emphasis on silent, continuous meditation, and its intimate integration with daily life resonated with the ethos of the common people.

Sōtō monasteries like Eihei-ji and Sōji-ji remained great centers of training and ritual, preserving the monastic codes and silent rhythms of medieval Zen life.

Ōbaku Zen

A third Zen stream, Ōbaku-shū, arrived in Japan in the seventeenth century, introduced by Chinese monks fleeing the collapse of the Ming dynasty. Ingen Ryūki (1592–1673) established the Ōbaku school at Manpuku-ji in Uji. Ōbaku Zen preserved Chinese language chanting, Pure Land practices alongside Zen meditation, and brought with it new artistic and culinary traditions, enriching the diversity of Japanese Buddhism.

Zen Aesthetics and Culture

During the Edo period, Zen permeated the arts as deeply as it shaped spiritual practice. Zen ideals of simplicity, impermanence, naturalness, and quiet profundity manifested in:

- Sumi-e (ink painting), where sparse, expressive brushstrokes captured the essence of a scene or moment.

- Haiku poetry, perfected by masters like Matsuo Bashō, who distilled vast emotions into just seventeen syllables.

- Chanoyu (the tea ceremony), which became a Zen-infused ritual celebrating simplicity, mindfulness, and the beauty of imperfection.

- Zen gardens, such as those at Ryōan-ji, which used rocks, moss, and carefully raked sand to evoke profound meditative states.

Zen disciplines also continued to influence martial arts, with swordsmanship, archery, and even calligraphy viewed as paths to spiritual realization.

Monastic Life in the Edo Period

Monastic life during the Edo period was structured yet accessible. Novices underwent rigorous training, learning not only meditation but also scripture recitation, liturgy, etiquette, and manual labor. Monks and nuns lived communally, following strict monastic codes (Vinaya and internal temple rules), but also participated in festivals, pilgrimages, and temple maintenance.

Despite the rigid state control, the monastic world remained dynamic. New interpretations of Zen arose, reform movements spread, and monks often traveled the countryside as mendicants, teachers, or wandering poets.

The spiritual heart of Japanese Zen during the Edo period lay not only in isolated monasteries but also in the lives of ordinary people who, even if they never donned robes, embodied the spirit of Zen in daily life.

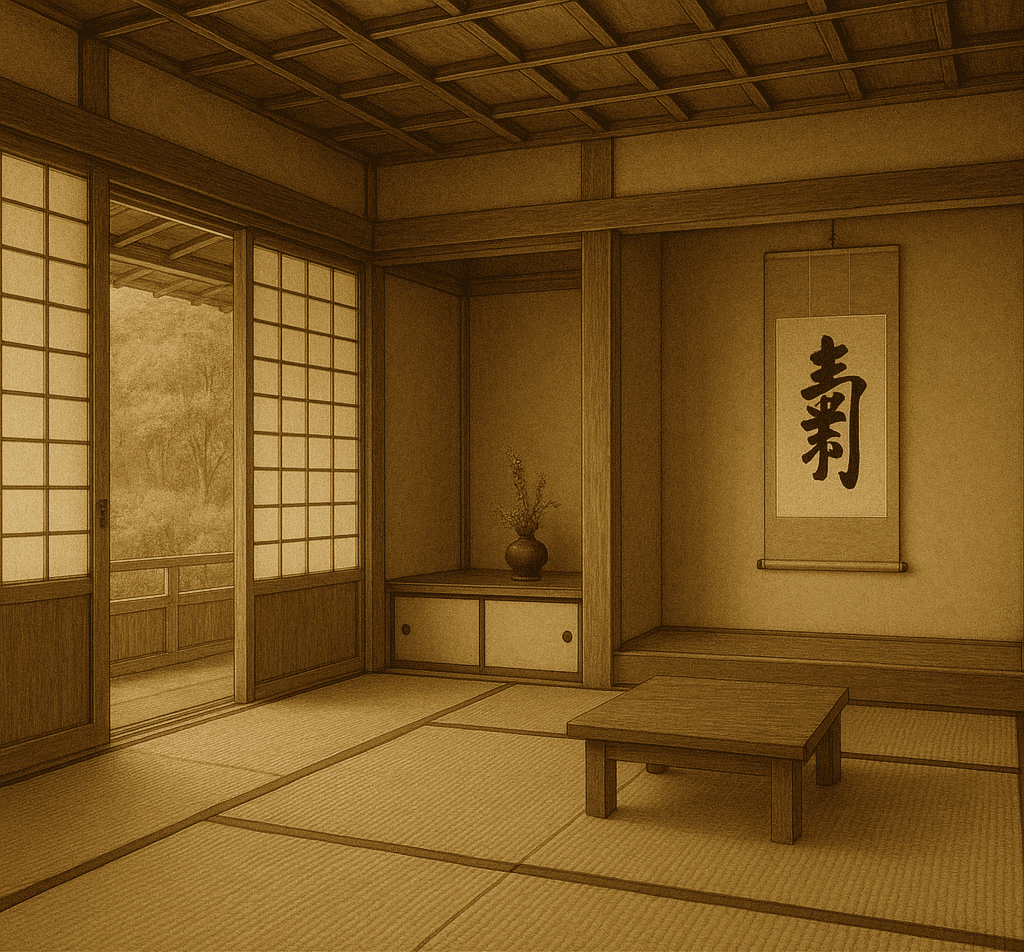

Monastic Architecture and Interiors: The Space of Awakening

The architecture and interiors of Japanese Buddhist monasteries are deeply expressive of the ideals of monastic life. Far more than functional buildings, monasteries (sōrin 僧林, “monks’ forest”) are themselves part of spiritual training—physical spaces that embody and nurture the path toward awakening. The austere beauty, careful proportions, and symbolic layout of Japanese monastic complexes reflect centuries of artistic refinement and religious meaning.

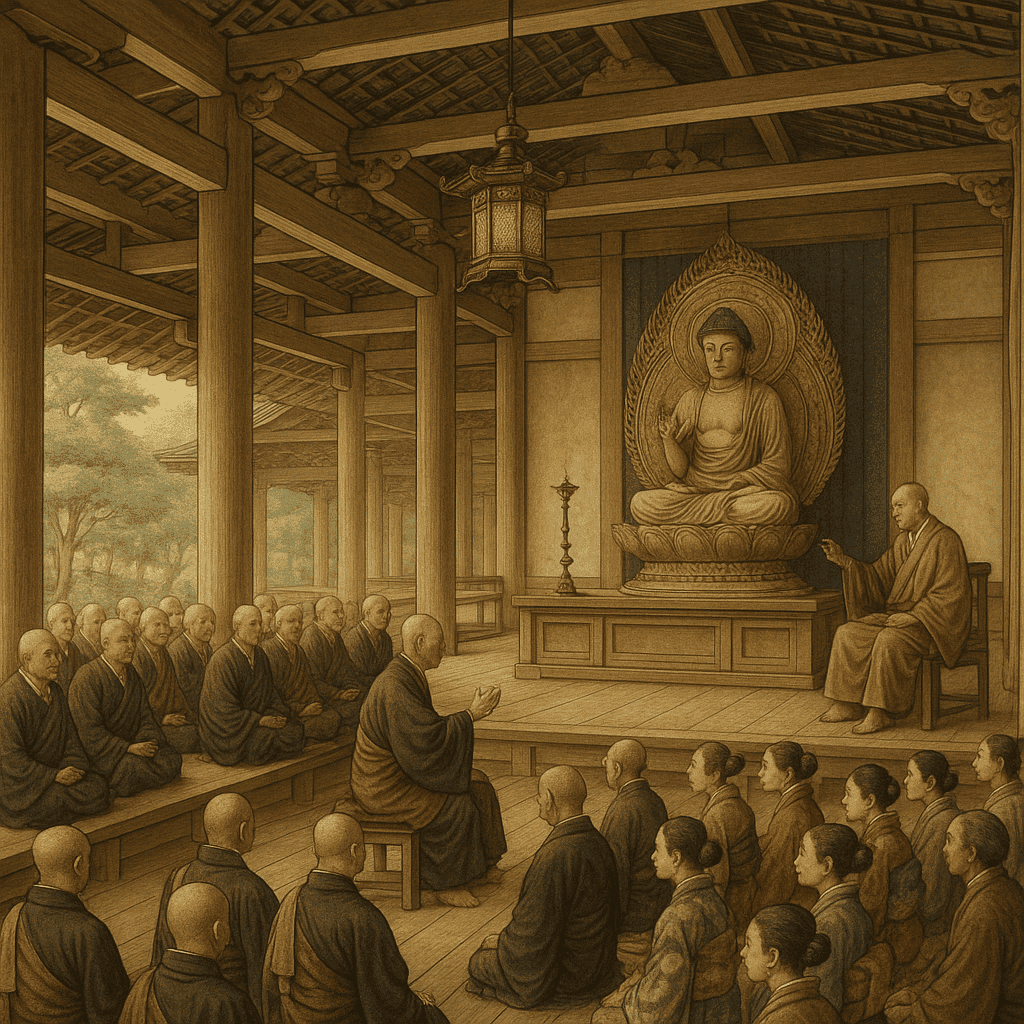

The Layout of a Monastery

Japanese Buddhist monasteries were originally modeled after Chinese Tang dynasty temples, adapted to Japan’s own climate, geography, and aesthetics. A typical monastic complex is arranged according to a formal, axial plan emphasizing symmetry and hierarchy. Key elements include:

- Sanmon (Mountain Gate): The great entrance gate, symbolizing the threshold between the profane world and the sacred space of practice. Passing through the sanmon is an act of inner purification.

- Butsuden or Hondō (Main Hall): The central building housing the principal image of veneration, such as a statue of Shakyamuni Buddha, Amida Buddha, or Kannon (Avalokiteśvara). It is the heart of ceremonial life.

- Hattō (Dharma Hall): The lecture hall where sermons (Dharma talks) are delivered and sutras are chanted.

- Sōdō (Monks’ Hall): The communal living and meditation space for monks. Here, zazen is practiced, meals are eaten, and monks sleep, usually seated upright.

- Kuri (Kitchen and Administrative Area): The center of daily logistics and communal service.

- Jiki-dō (Dining Hall): In some temples, a separate hall for eating; in strict Zen monasteries, eating may occur in the Sōdō.

- Kyōzō (Sutra Repository): A building to store sacred texts.

- Bathhouse and Toilets: Monasteries traditionally maintain ritual cleanliness, and the bathhouse (yokushitsu) has symbolic importance as a place of bodily and spiritual purification.

Many Zen monasteries also include a kōdō (bell tower) and shōrō (drum tower), used to mark the passage of time and signal communal activities.

The entire monastery is typically enclosed by walls and surrounded by gardens designed to aid contemplation, with carefully raked sand, moss gardens, ponds, and paths meandering through natural or stylized landscapes.

Interior Spaces and Monastic Furniture

Inside the monastery buildings, the interiors are deliberately minimalist. This simplicity supports the practice of mindfulness and detachment, removing distractions and cultivating awareness of the present moment.

Key interior elements include:

- Tatami Flooring: Rooms are covered with tatami mats—woven straw mats of uniform size—which regulate space, movement, and formality. The texture and slight fragrance of tatami help create a sensory atmosphere of calm.

- Shōji Screens: Sliding doors made of wood and translucent paper diffuse light, create subtle boundaries, and maintain fluidity between interior spaces.

- Tokonoma (Alcove): In formal guest rooms or abbot’s quarters, a small alcove displays a single hanging scroll (kakemono) and a flower arrangement (ikebana). The scroll may feature a Zen calligraphy or a simple painting, offering an object for quiet appreciation and reflection.

Furniture is spare, portable, and purpose-driven:

- Zafu (Meditation Cushion): A round, firm cushion placed on a flat mat (zabuton) to elevate the hips and support a balanced sitting posture during zazen.

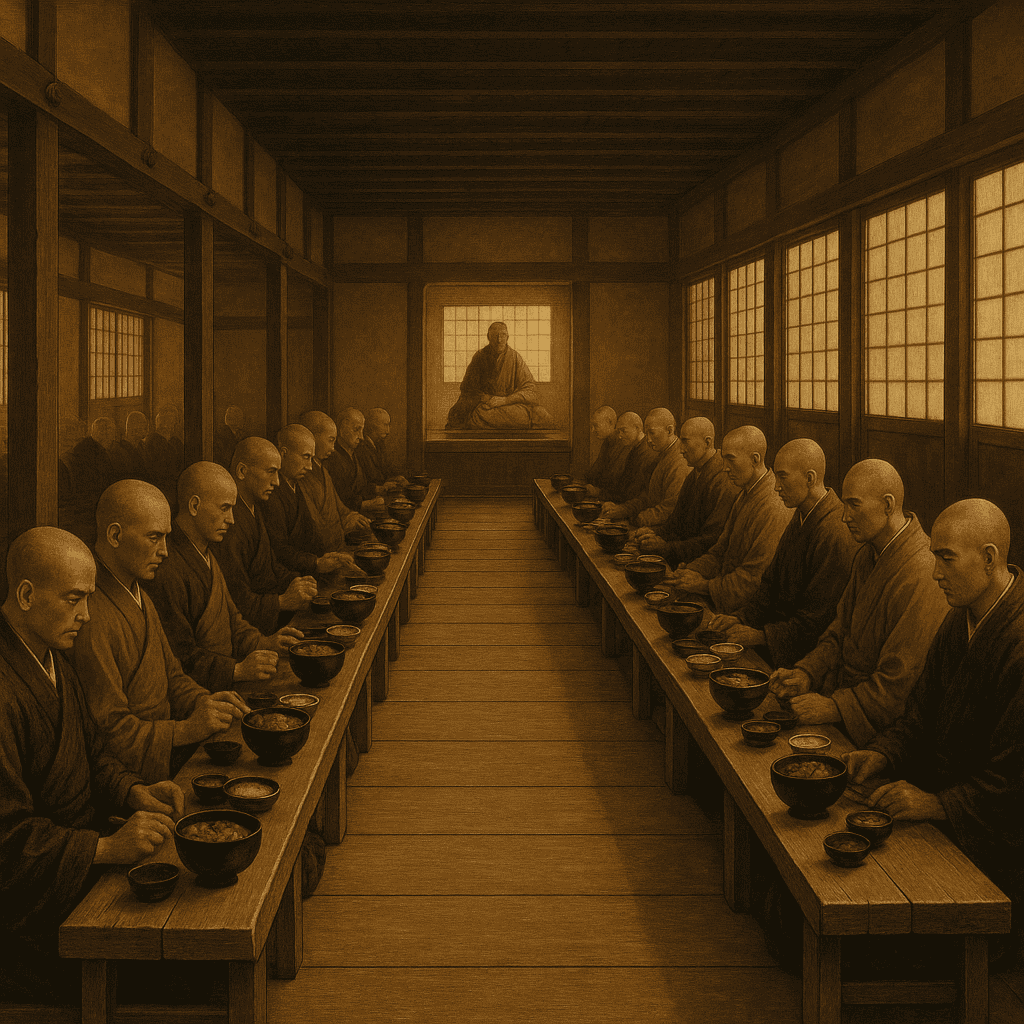

- Low Tables: Used for communal meals or sutra study, emphasizing equality and humility.

- Wooden Platforms (tan): In the Sōdō (monks’ hall), monks sit, eat, and sleep on raised wooden platforms lined with tatami mats. The same platform becomes a bed and a meditation seat, symbolizing the integration of all activities into spiritual practice.

- Kaiseki Tray: A personal eating tray and bowls used during the formalized monastic meals (oryoki). The ritual of oryoki emphasizes gratitude, mindfulness, and economy of movement.

In strict Zen monasteries, even the placement of a single cushion or bowl follows precise etiquette, reinforcing awareness and discipline.

Symbolism of Space and Structure

Every part of a monastery carries symbolic meaning:

- Straight Paths and Open Spaces: Reflect the straightforwardness of the Way and encourage unobstructed awareness.

- Natural Materials (wood, paper, stone, straw): Symbolize impermanence (anicca) and interconnectedness with the natural world.

- Minimalism: Embodies the Zen ideal that nothing extraneous should clutter the mind or the environment.

- North-South Orientation: Many temples are aligned along a north-south axis, a traditional symbol of cosmic order and harmony with the universe.

Ultimately, the monastery is not just a place to live—it is a living teaching. To walk through its gates, to bow before the Buddha, to sit silently on the worn tatami, is to move through a world intentionally crafted to mirror and support the journey toward liberation.

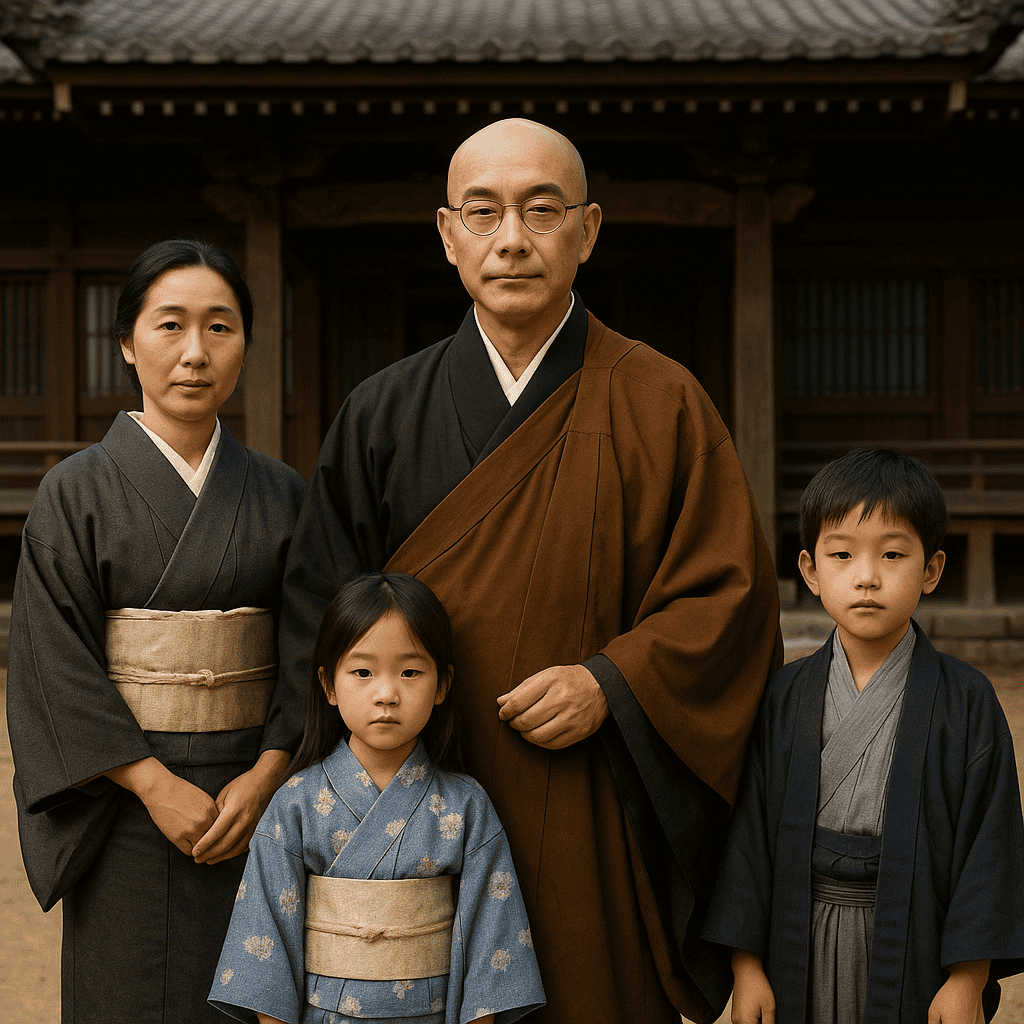

A Day in the Life of a Japanese Buddhist Monk or Nun

The life of a Japanese Buddhist monastic is one of simplicity, discipline, and devotion. Each day is carefully structured to support the central aims of the path: mindfulness, compassion, and awakening. The rhythm of monastic life weaves together meditation, ritual, study, communal labor, and silent awareness, all shaped by the ancient ethical codes and liturgical traditions that continue to guide Buddhist communities across Japan.

The Monastic Precepts

Upon ordination, monks (bhikṣu) and nuns (bhikṣuṇī) vow to uphold a set of ethical guidelines known as the precepts (kai 戒). These include:

- The Five Precepts (common to lay and monastic practitioners):

- Abstaining from killing.

- Abstaining from stealing.

- Abstaining from sexual misconduct.

- Abstaining from false speech.

- Abstaining from intoxicants.

- Abstaining from killing.

Ordained monks and nuns also take additional vows of celibacy, poverty, obedience, and devotion to practice. In stricter sects, monastics follow versions of the full Vinaya code, which can include hundreds of detailed rules regulating behavior, clothing, diet, and interaction with society.

The precepts are not seen as arbitrary commands but as supports for a life free from craving, aversion, and delusion.

Daily Schedule

A typical day in a traditional monastery unfolds according to a timeless rhythm:

- 3:30–4:00 AM:

Wake-up bell (kaichin). The day begins in the still darkness with chanting or a brief meditation session to center the mind. - 4:30 AM:

Zazen (seated meditation). Monks and nuns gather in the meditation hall (sōdō) for periods of silent sitting, often in darkness or candlelight. - 6:00 AM:

Morning Service (chōka 朝課). Chanting of sutras, such as the Heart Sutra (Hannya Shingyō) or the Lotus Sutra, accompanied by prostrations and offerings of incense. - 7:00 AM:

Breakfast (shōjin ryōri 精進料理). A simple, vegetarian meal eaten mindfully, often in the formal oryōki style, where each monk has a personal set of nested bowls and follows a highly ritualized meal procedure emphasizing gratitude and economy. - 8:00 AM–12:00 PM:

Samu (作務), communal work. Tasks vary by season and need: cleaning, gardening, cooking, repairing buildings, chopping firewood. Manual labor is seen as an extension of meditation. - 12:00 PM:

Lunch (the main meal of the day), eaten in similar mindful silence. After lunch, traditional Vinaya rules prohibit monks from eating solid food until the next morning, though modern monasteries may adapt this according to climate and custom. - 1:00–3:00 PM:

Study and Practice. Monastics engage in the study of sutras, commentaries, or memorize liturgical texts. Some periods may include kōan introspection (in Zen), Dharma talks, or interviews (dokusan) with a teacher. - 3:00–5:00 PM:

Afternoon Work and Free Practice. Monks and nuns continue communal tasks or personal meditation. - 5:30 PM:

Evening Service (yūka 夕課). Another short chanting ceremony, often dedicated to all sentient beings. - 6:00–9:00 PM:

Zazen and light personal study or devotional practices. - 9:00 PM:

Lights out (kaichin). Monks and nuns sleep in the meditation hall, usually seated upright on their platforms (tan), wrapped in robes, maintaining mindfulness even during rest.

The daily schedule varies slightly depending on the season, special training periods (ango 安居), or preparations for festivals and ceremonies.

Monastic Robes and Possessions

Simplicity governs even the belongings of a monk or nun. Personal possessions are minimal and symbolic:

- Kesa (袈裟): The formal outer robe, stitched together from small pieces of cloth to symbolize humility and interconnectedness. Worn during ceremonies and formal meditation.

- Koromo (衣): The everyday working robe, simple and functional, usually black or dark brown.

- Rakusu (絡子): A miniature, bib-like kesa worn around the neck, often by novice monks or lay practitioners who have taken the precepts.

- Oryōki Bowls (応量器): A set of nested eating bowls wrapped in cloths, used in formal meals. Oryōki emphasizes gratitude, non-wastefulness, and mindful eating.

- Zagu (坐具): A small mat used under the zafu during meditation and ceremonies.

- Mokugyo (木魚): A wooden fish-shaped drum used to keep rhythm during chanting.

- Kotsu (骨): A symbolic hand staff sometimes carried by Zen teachers during ceremonies, representing the “backbone” of the Dharma.

Each item is treated with reverence, maintaining mindfulness even in the simplest acts—folding robes, cleaning bowls, or preparing a sitting mat.

Monastic Diet

Diet in a Japanese Buddhist monastery follows the principles of shōjin ryōri (“devotional cuisine”). It is:

- Vegetarian: No meat, fish, or animal products that involve taking life.

- Seasonal and Local: Ingredients reflect the changing seasons and the monastery’s immediate surroundings.

- Simple and Balanced: Meals often include rice, miso soup, seasonal vegetables, pickles, tofu, seaweed, and sometimes foraged mountain herbs.

The preparation and consumption of food are part of spiritual training. Gratitude is expressed not only in prayer but in minimizing waste, savoring the inherent purity of ingredients, and recognizing the interdependence of all life.

The Liturgical Calendar

The monastic year is punctuated by festivals and special observances:

- Rohatsu Sesshin (December 1–8): An intensive meditation retreat commemorating the Buddha’s enlightenment, culminating in an all-night meditation on December 8.

- Obon (July or August): A festival honoring the spirits of ancestors, involving ritual offerings and ceremonies.

- Ullambana (similar to Obon): A service for the liberation of beings suffering in lower realms.

- O-Bon-e (February 15): Nirvana Day, commemorating the Buddha’s passing into final nirvana.

- Ango (summer and winter “peaceful dwelling” periods): Intensive three-month monastic training seasons of heightened discipline.

Festivals are occasions for increased ritual activity, community engagement, and often offerings to the laity who support the monastery.

Rohatsu Sesshin – A Week of Awakening

Rohatsu Sesshin (臘八摂心) is the most intense meditation retreat in the Zen monastic calendar, held from December 1–8 each year to commemorate the Buddha’s enlightenment under the Bodhi Tree.

During this week, monks, nuns, and dedicated lay practitioners sit in relentless meditation from pre-dawn until late at night, pushing the body and mind to the very brink in the hope of breaking through to awakening (satori).

A typical daily schedule during Rohatsu Sesshin might look like:

- 3:00 AM — Wake-up bell. Silent washing and preparation.

- 3:30–5:30 AM — Zazen (seated meditation).

- 5:30–6:00 AM — Chanting service (chōka), sutra recitation.

- 6:00–6:30 AM — Light breakfast (gruel and pickles).

- 6:30–11:00 AM — Multiple rounds of zazen with short walking meditation (kinhin) between.

- 11:00–11:30 AM — Oryōki lunch, eaten in formal, mindful silence.

- 12:00–5:00 PM — Continuous rounds of zazen and kinhin. Private interviews (dokusan) with the teacher may occur.

- 5:00–5:30 PM — Light evening meal (often just pickles and tea).

- 6:00–9:00 PM — Evening zazen.

- 9:00–11:00 PM — Night sitting continues, especially as the week deepens.

In some monasteries, during the final night (December 7–8), practitioners sit all night without sleep, holding nothing back in their pursuit of awakening.

By the dawn of December 8th, after a week of profound physical exhaustion and mental clarity, the community celebrates the Buddha’s enlightenment with chants, prostrations, and a simple, joyful meal.

Rohatsu embodies the heart of Zen: fierce determination, silent perseverance, and sudden illumination.

The Meiji Restoration and the Modern Challenges to Japanese Monasticism

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 marked a profound turning point in Japanese history. After more than two centuries of isolation and feudal rule under the Tokugawa shogunate, Japan rapidly opened its doors to the world, embracing modernization, industrialization, and Western ideas at a breathtaking pace. Amid this transformation, Buddhist monasticism—so deeply woven into the fabric of premodern Japan—faced unprecedented challenges.

The Crisis of State Shinto and Anti-Buddhist Policies

One of the earliest and most devastating blows to traditional Buddhist institutions came from the new government’s policy of promoting State Shinto as the ideological foundation of national identity. In an effort to create a strong, centralized state religion untainted by “foreign” influences, the Meiji government officially separated Shinto from Buddhism through a campaign called shinbutsu bunri (神仏分離, “separation of kami and buddhas”).

This led to widespread haibutsu kishaku (廃仏毀釈, “abolish Buddhism and destroy Śākyamuni”), a violent anti-Buddhist movement in the early Meiji years. Thousands of Buddhist temples were destroyed, monks were defrocked or forcibly secularized, and Buddhist statues and sutras were burned or defaced.

Although the most extreme phases of haibutsu kishaku subsided after a few years, the damage was immense: Buddhist monastic communities shrank drastically, and their wealth and social influence were greatly reduced.

Secularization of Monastics

In a further attempt to modernize and “rationalize” religion, the Meiji government decreed that Buddhist monks:

- Were permitted to marry.

- Could eat meat.

- Were allowed to grow their hair.

While this created a more flexible system suited to the new, secular society, it also undermined centuries of monastic discipline and the ideal of the celibate, renunciant monk. Many monks embraced these changes, establishing Buddhist families and integrating more fully into ordinary life. Others, however, mourned the loss of the rigorous, austere monastic ideal.

The traditional model of a cloistered, celibate community living apart from society was replaced, in many cases, by a new model: the temple family (jike), where clerical office and temple duties were passed down from parent to child, much like a secular profession.

The Survival and Adaptation of Buddhist Monasticism

Despite these upheavals, Japanese Buddhism did not vanish. Instead, it adapted—often with remarkable creativity:

- Reform movements arose within various schools, seeking to reassert discipline and clarify doctrine.

- New Buddhist movements were founded, such as Risshō Kōsei-kai and Sōka Gakkai, combining Buddhist teachings with active lay participation and social engagement.

- Education and scholarship were revitalized. Monasteries and temples became centers not only of worship but also of modern Buddhist studies and public lectures.

- International outreach began. Japanese Buddhist teachers, particularly Zen masters, traveled abroad, planting seeds of Zen in Europe and America.

Some monastic communities, particularly within Zen (Rinzai and Sōtō) and Shingon schools, preserved stricter forms of practice. Intensive training monasteries (senninzendō) continued to maintain high standards of meditation, ritual, and discipline, though often on a much smaller scale than before.

Monasticism and the Modern Japanese Identity

By the early twentieth century, Buddhism had become an inseparable part of the evolving Japanese identity, though often more in the role of a cultural tradition than a daily spiritual path for the majority. Buddhist funerary rites, memorial services, and seasonal festivals kept the connection alive in public life, even as monastic numbers declined.

During the Second World War, some Buddhist institutions were drawn into nationalist ideologies, further complicating their role in modern Japan. After 1945, in the wake of defeat and democratization, Buddhist monasticism faced the dual challenges of rebuilding trust and relevance in a rapidly globalizing, increasingly secular society.

Yet the spirit of Japanese monasticism—the quiet discipline, the deep love of nature, the unbroken lineage of meditation and compassion—remained alive, a hidden river flowing beneath the tumultuous surface of modern history.

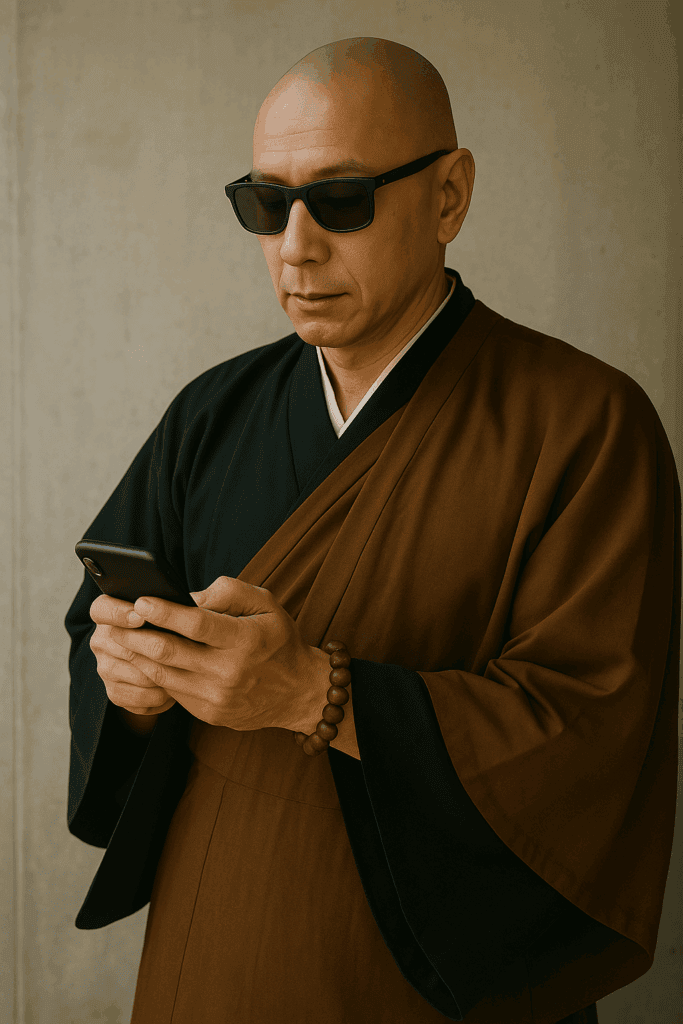

Japanese Monasticism Today: Revival, Globalization, and Contemporary Practice

In the twenty-first century, Japanese monasticism stands at a fascinating crossroads—rooted in ancient tradition, yet dynamically engaged with a rapidly changing world. Though the number of full-time monks and nuns remains smaller than in past centuries, the spirit of Japanese monastic life has adapted and flourished both within Japan and far beyond its shores.

A Quiet Revival

In Japan itself, a quiet revival of monastic training has been underway since the mid-twentieth century.

Some traditional monasteries—especially Zen sōdō (training halls) like Eihei-ji (Sōtō school) and Myōshin-ji (Rinzai school)—continue to uphold rigorous, multi-year monastic training. Young monks, often coming from temple families, undergo intense periods of meditation (zazen), liturgical practice, communal labor (samu), and strict adherence to monastic codes.

While temple families and clerical marriage are still widespread, there has been renewed interest in deeper monastic commitment, spurred partly by disillusionment with consumer society and a longing for authentic spiritual practice.

Zen and Buddhism Go Global

Perhaps the most remarkable modern development is the global spread of Japanese monastic practices, especially Zen Buddhism.

- Rinzai Zen was introduced to the West by figures like D.T. Suzuki, who translated and interpreted Zen teachings for global audiences, blending scholarly insight with profound experiential wisdom.

- Sōtō Zen found a major international voice through masters like Shunryu Suzuki (author of Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind), who founded the San Francisco Zen Center and helped establish formal monastic practice for Western lay and ordained practitioners.

- Kōshō Uchiyama, Taisen Deshimaru, Seung Sahn, and many others helped to plant Zen centers and monasteries across Europe, the Americas, and beyond.

Today, Japanese-style Zen monasteries exist across the world, from remote rural temples to urban zendos, welcoming a diverse range of seekers, lay practitioners, and ordained monks.

Japanese Buddhism has also contributed deeply to the global mindfulness movement, influencing fields as diverse as psychology, education, leadership, and the arts.

New Forms of Monastic Engagement

Contemporary Japanese monks and nuns engage with society in new ways:

- Some have become teachers and counselors, helping people cope with grief, depression, and the stresses of modern life.

- Others have established “urban temples” (machidera) that serve city-dwellers who seek moments of quiet and spiritual reflection amid hectic lives.

- Buddhist responses to environmental crises, peace movements, and interfaith dialogues have expanded the role of monastics beyond temple walls.

- New monastic-inspired movements, such as Engaged Buddhism, call for monks, nuns, and laypeople alike to embody compassion through social action, not just inner cultivation.

Monasteries themselves are changing: some now offer short-term retreats, secular meditation programs, or training periods for foreigners, opening their ancient gates to a truly global audience.

Challenges and Hopes

Despite the vitality of modern developments, challenges remain. Traditional monastic communities face an aging population, declining rural temple membership, and financial pressures. The balance between preserving ancient forms and adapting to contemporary needs requires careful, sensitive navigation.

Yet Japanese monasticism endures. Its heart remains unchanged: a daily rhythm of mindfulness, simplicity, and gratitude; a reverence for impermanence and the interconnection of all beings; and the humble aspiration, still quietly spoken in temple halls and mountain hermitages, to awaken for the benefit of the world.

In the silence of dawn meditation, the ancient bell still rings out, calling monks, nuns, and seekers across the world to sit upright, breathe deeply, and walk the endless Way.

Conclusion: The Living Tradition of Japanese Monasticism

Across the long arc of Japanese history, monasticism has been a quiet yet powerful force—shaping culture, governance, spirituality, and the very spirit of the nation itself. From the ancient mountain shrines of Shinto priests to the grand Buddhist monasteries of Nara and Kyoto; from the disciplined austerity of Kamakura Zen warriors to the delicate refinements of Edo-period tea masters; from the profound challenges of the Meiji Restoration to the global Zen centers of today—Japanese monasticism has adapted without ever losing its essential heart.

The monastery, whether nestled in a misty forest or hidden within a city’s bustle, remains a sanctuary of mindful living. Its rhythms—silent meditation, humble meals, daily labor, ritual chanting—are a training ground for awakening, teaching that true freedom lies not in external circumstances but in the patient, fearless turning inward.

In the modern world, where distractions multiply and meaning can feel elusive, the ancient bells of Japanese monasteries still ring out—calling not just monks and nuns, but anyone willing to listen, to return to stillness, to rediscover the clarity and compassion that lie hidden in the heart of each moment.

As Zen Master Dōgen once wrote:

“To study the Way is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be awakened by all things.”

Japanese monasticism endures not as a relic of the past, but as a living invitation—an open gate—for all who seek to walk the endless Way of wisdom, humility, and boundless compassion.

Inside Monastic Culture Series

Virgins and Philosophers: Early Proto-Monasticism

From Hermits to Orders: The Solitary Roots of Monastic Culture

The First Monks Rise in the East: The Birth of Monasticism

Christian Monasticism, University, and Lectio Divina Meditation

Monks of War: The Military Orders

The Confucian Monastic Tradition

The Evolution of Japanese Monastic Life

Soto Zen from India to America

AUTHOR

D. B. Smith is an independent historian, ritualist, and comparative religion scholar specializing in the intersections of Western esotericism, Freemasonry, and Eastern contemplative traditions. He formerly served as Librarian and Curator at the George Washington Masonic National Memorial, overseeing historically significant artifacts and manuscripts, including those connected to George Washington’s personal life.

Initiated into The Lodge of the Nine Muses No. 1776, a philosophically focused lodge in Washington, D.C., Smith studied under influential figures in the Anglo-American Masonic tradition. His work has been featured in national and international Masonic publications, and his efforts have helped inform exhibits, lectures, and a televised documentary on the history and symbolism of Freemasonry.

Smith’s parallel study and practice of Soto Zen Buddhism—including ordination as a lay practitioner in the Katagiri-Winecoff lineage—has led him to investigate convergences between ritual, mindfulness, symbolic systems, and the evolving role of spiritual practice in secular societies. He is the founder of Science Abbey, a platform for interdisciplinary inquiry across religion, philosophy, science, and cultural history.