Inside Monastic Culture Series Part IX

Introduction: The Way Beyond Words

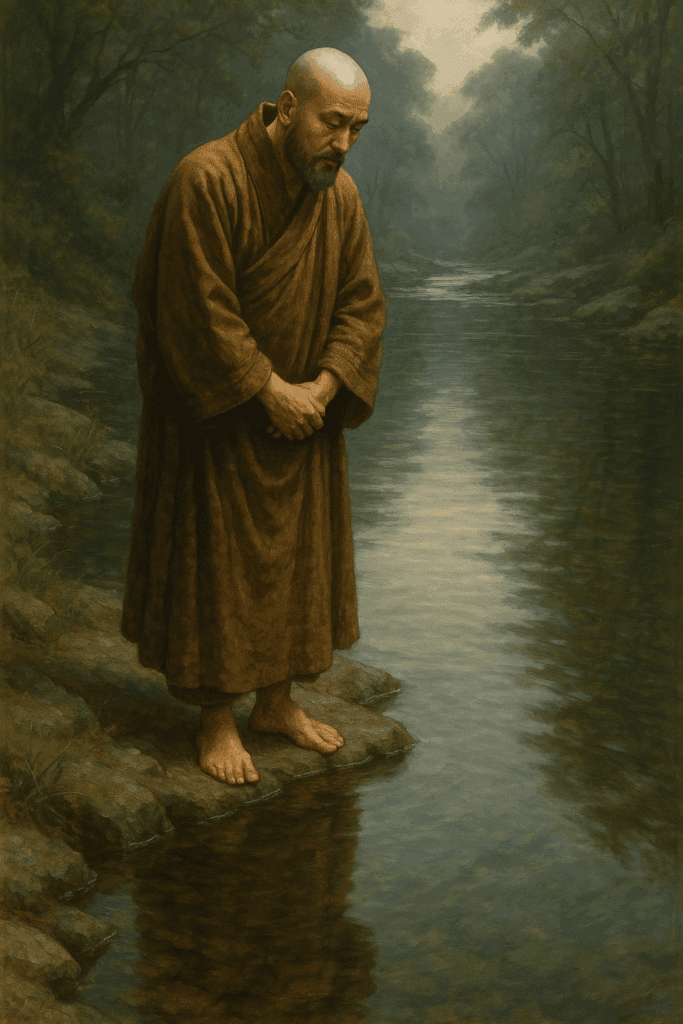

In the remote mountains of China, centuries ago, monks rose before dawn.

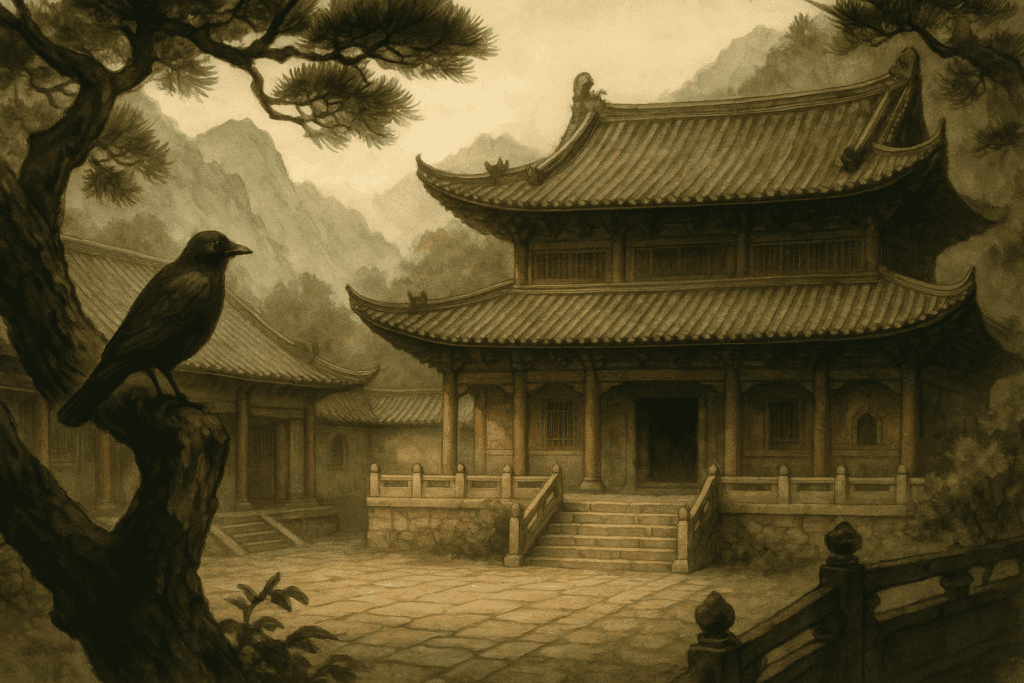

They moved through stone halls in silence, offering incense to the ancestral seat. They sat in stillness, facing walls. They swept courtyards and washed bowls with quiet care. They neither sought enlightenment nor denied it. They practiced.

This was the life of Chan monasticism—a tradition at once austere and luminous, rooted in silence yet filled with meaning.

Emerging in China during the sixth century, Chan (Zen in Japan, Seon in Korea, Thiền in Vietnam) transformed Buddhism.

Where previous schools had emphasized doctrine, cosmology, or devotional ritual, Chan returned to the simplicity of sitting and seeing. It offered no promise beyond this moment. It taught that Buddha-nature is not to be attained, but realized—as the very nature of the one who seeks.

This article follows the story of Chan from its earliest roots in India and Daoist China, through its flowering in Tang and Song dynasties, and outward into the temples, poetry, and practices of East Asia.

We walk the path of wandering ascetics and mountain abbots, of silent zazen and poetic dialogue, of monastic halls and modern meditation centers. We trace its rhythms—from the crack of the wake-up board to the stillness of midnight zazen—and its teachings, passed not through scripture alone, but through presence, posture, and paradox.

Chan monastic life is not a retreat from the world, but a return to what is real beneath illusion.

Through its architecture, its meditation halls, its robes and its rules, the Chan monastery becomes not a monument to the past, but a living enactment of the Dharma. A place where the formless is practiced in form.

Today, in places as diverse as New York, Taipei, Kyoto, Seoul, Hue, and Bordeaux, the spirit of Chan continues.

In the footsteps of Bodhidharma, Hongren, Huineng, Linji, Dongshan, and so many others, contemporary teachers remind us that the transmission is not broken. It passes through breath, gaze, silence, step.

Chan does not ask us to believe. It invites us to look.

And if one listens deeply enough,

beneath the sound of chanting or the sweep of the broom,

beneath the mountain wind and the hush of dusk—

one may hear the ancient teaching,

spoken without a single word.

Politics and Monasticism in East Asia

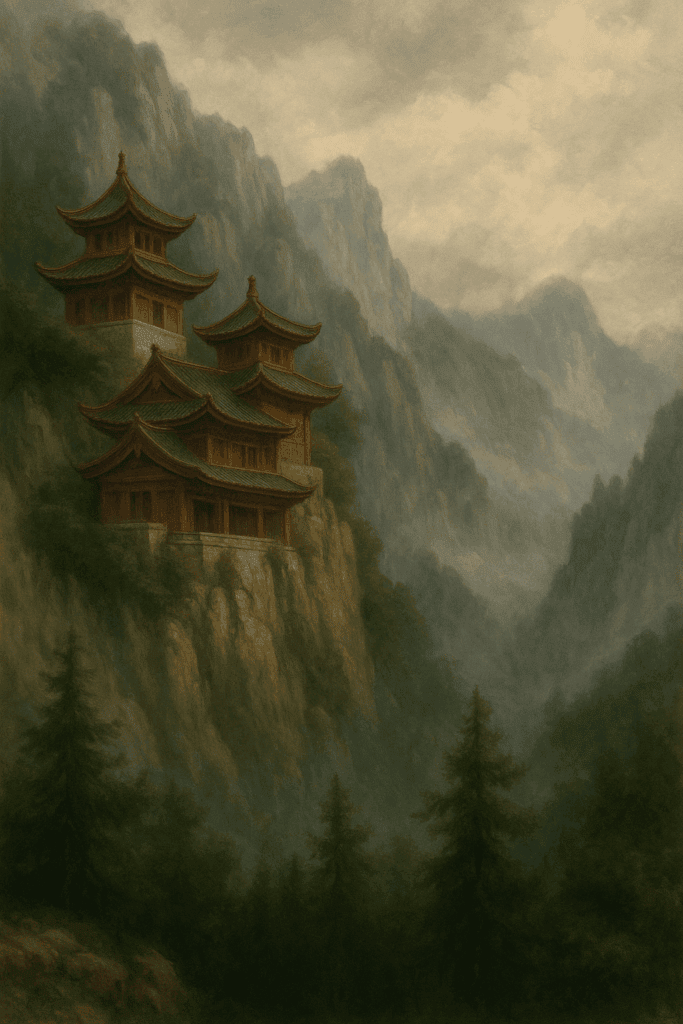

By the time Bodhidharma crossed the rivers and mountain passes into China, Buddhism had already taken deep root in East Asia. Monasteries had grown into powerful institutions. They were no longer only places of quiet retreat, but also centers of learning, diplomacy, and political presence.

From the early centuries of the Common Era, the Buddhist sangha in China began to take shape around the disciplinary codes of the Vinaya. Indian monastic regulations—such as the Ten Recitation Vinaya and the Four-Part Vinaya—were translated into Chinese and adapted into communal life. These laid the foundation for a distinctly Chinese Buddhist order, characterized by discipline, ethical conduct, and a structured community.

Monks such as Daoan (312–385) and later Daoxuan (596–667) helped codify monastic life.

Daoan’s Standards for the Clergy and Charter for Buddhism, though lost, left a legacy of organizational clarity. Daoxuan’s scholarship preserved historical accounts and set the tone for the Lü (Vinaya) school, which would shape the daily rhythms of Chan monasteries for generations to come.

Monastic life did not remain isolated. Monks engaged in public discourse, gave sermons, and debated with Daoist and Confucian scholars—even in the presence of emperors.

Teachings were often centered on scriptures like the Lotus Sutra or Avatamsaka Sutra. These public teachings, sponsored by aristocratic lay patrons, supported monastic institutions financially and helped integrate Buddhism into the broader cultural landscape.

Temples became active participants in political life.

The Shaolin Monastery at Mount Song became a notable example. Though best known today for its martial tradition, it was initially a center of meditation and monastic discipline. Over time, its monks developed martial skills as a form of physical cultivation, protection, and, in some cases, military service.

This was the world Bodhidharma entered—a world where Buddhism was respected, supported, and politically engaged, but also in danger of becoming overly institutionalized.

According to legend, Bodhidharma’s response was silence. He retreated to a cave, turned his back on worldly power, and meditated facing the wall for nine years. This quiet act would come to symbolize the essence of Chan: a turning inward, away from words and forms, toward direct realization.

Though Chan would inherit the structures of early Chinese monasticism, it began to move in a new direction.

It honored the Vinaya (monastic rule), preserved the role of the sangha (Buddhist community), and accepted the value of teaching—but placed awakening at the center. Chan monks were not bound to temple walls or palace debates. They were free to sit, walk, wander, or sweep floors, practicing wherever the mind could be still.

The stage was now set. In the centuries to follow, Chan would grow from a subtle undercurrent into one of the great spiritual traditions of East Asia.

The Arrival of Bodhidharma and the Foundations of Chan

Chan Buddhism, known for its simplicity and directness, begins with a story of silence.

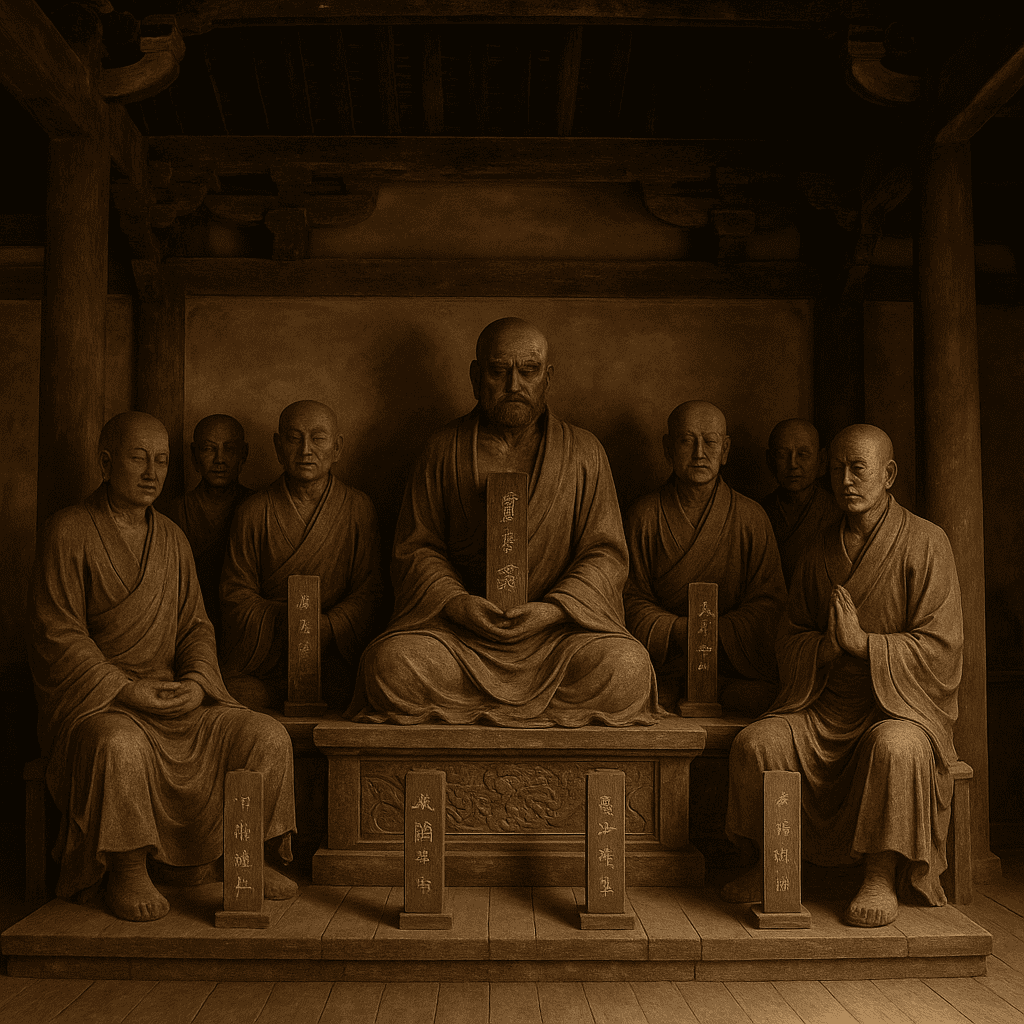

According to tradition, the Buddha once held up a white flower before his assembly. None spoke. Only Mahākāśyapa smiled. In this wordless gesture, the Buddha transmitted something beyond scripture—what Chan calls the “mind-seal,” a direct pointing to the nature of awareness itself. That gesture, and that smile, mark the origin of the Chan lineage.

Twenty-eight generations later, the Indian monk Bodhidharma carried this transmission to China.

He arrived sometime between the late fifth and early seventh centuries CE, during a time of dynastic transition and religious diversity. Known in Chinese as Da Mo, Bodhidharma is said to have come from South India, possibly a Brahmin prince who renounced his heritage to become a Buddhist monk. Other traditions, including later Japanese accounts, suggest Persian origins. Chinese sources simply call him “the Blue-eyed Barbarian.”

Bodhidharma brought with him the teachings of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, a text rooted in Yogācāra and Tathāgatagarbha thought. It teaches that reality is a projection of mind, and that enlightenment is attained not through ritual or doctrine, but through direct insight. Early Chan monks were often called “Laṅkāvatāra Masters,” and their school was known as the “One Vehicle School” for its focus on the universal potential for Buddhahood.

According to legend, Bodhidharma reached the Shaolin Temple on Mount Song around 527 CE.

Rather than teaching immediately, he withdrew to a cave behind the temple and sat in silent meditation—biguan, or “wall gazing”—for nine years.

The temple itself had been founded several decades earlier for the Indian monk Buddhabhadra, and already had martial practitioners among its monastic community. Bodhidharma is said to have contributed exercises to strengthen the body for meditation, planting the seeds for what would become the famed Shaolin martial arts.

It is also said that Bodhidharma introduced tea to the monks to help them remain alert during long meditation. In iconography, he is sometimes depicted with bulging eyes, unable to close them.

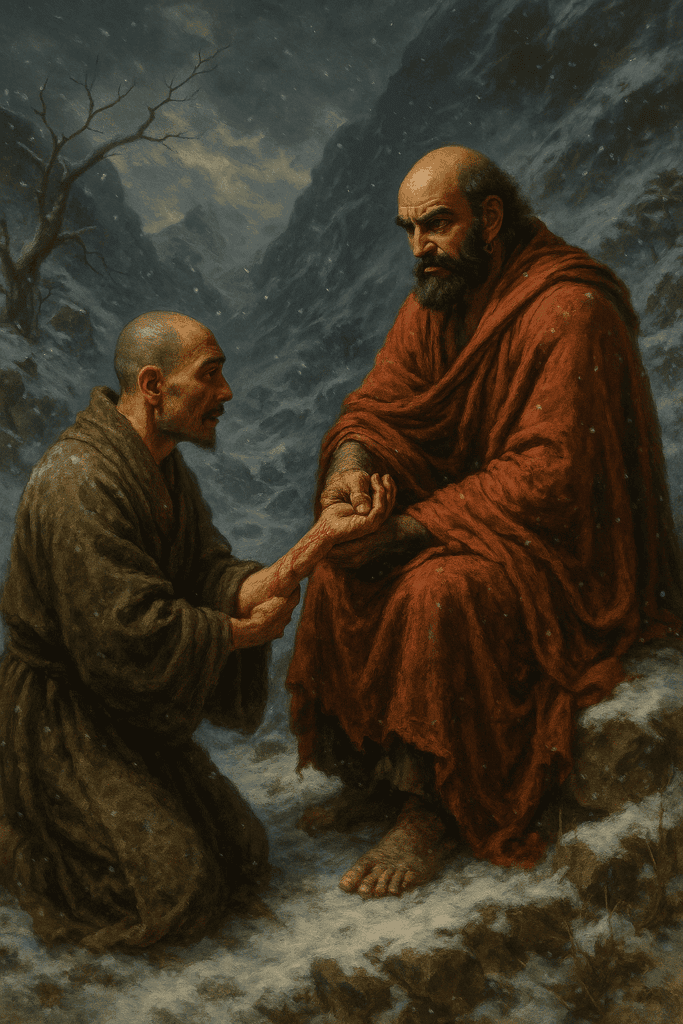

One of the most enduring legends concerns a seeker named Shen Guang (“Divine Light”).

Determined to receive Bodhidharma’s teaching, he stood outside the cave in snow for days. When Bodhidharma still refused him, he severed his own arm as a demonstration of sincerity.

Moved, Bodhidharma accepted him as a disciple, gave him the Dharma transmission, and renamed him Dazu Huike (“Wise and Capable”). Huike received a robe, a bowl, and a copy of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra. He became the Second Patriarch of Chan, and the first Chinese-born heir to the tradition.

Bodhidharma’s teachings, though few in number, are preserved in a text known as the Outline of Practice.

In it, he speaks of two gates to the Way: one of principle (li), meaning deep meditation or non-doing (wu wei), and one of practice (xing), meaning daily cultivation. He outlines four essential practices: enduring hardship with patience, adapting to conditions without attachment, ceasing to seek, and living according to virtue—especially through acts of generosity.

(Read the Outline of Practice)

Other sermons ascribed to him—such as the Wake-Up Sermon, Bloodstream Sermon, and Breakthrough Sermon—were likely written by later disciples, preserving his voice in the evolving Chan tradition.

(Translations of Bodhidharma’s works)

Bodhidharma and Huike lived simply, moving through mountains and temples, free from fame or possession.

They were ascetics, but not removed from the world. Their practice was quiet, yet revolutionary. They taught that enlightenment was not something distant, to be earned through lifetimes of effort, but something immediate—found in the mind that sees clearly.

This spirit—direct, silent, and fiercely independent—formed the heart of Chan.

From Bodhidharma’s cave, a lineage would grow. His followers would continue the work he began, shaping Chinese Buddhism into a path of presence, simplicity, and profound insight.

The First Patriarchs of Chan Buddhism

After Bodhidharma and Huike, the early Chan lineage was preserved by a small group of practitioners who lived outside the centers of power.

They wandered through forests and mountains, taught few disciples, and spoke sparingly. Their lives were marked by simplicity, silence, and deep trust in the mind’s capacity for awakening.

The Third Patriarch was Jianzhi Sengcan (d. 606), a figure cloaked in mystery.

He is best known for the Xinxin Ming—“Trust in Mind” or “Faith in True Mind”—a poetic statement of Chan’s essential insight. In it, all dualities dissolve: self and other, right and wrong, emptiness and form. The path, Sengcan wrote, is not found through striving, but through letting go.

(Read the Xinxin Ming)

Sengcan lived for many years in retreat, reportedly hiding from persecution.

When he reemerged, he resumed the life of a mendicant. He was accompanied for nearly a decade by a devoted student named Dayi Daoxin. Sengcan eventually passed away beneath a tree, resting before a Dharma assembly. With his death, the transmission passed to Daoxin.

Dayi Daoxin (580–651), the Fourth Patriarch, marked a subtle turning point in the tradition.

Unlike his predecessors, he began to settle. He founded a small monastic community on Mount Potou—later called Shuangfeng or “Twin Peaks”—in Huangmei County, Hubei Province.

There, Daoxin taught a form of meditation that integrated seated practice with daily activity. His teachings were simple, direct, and embodied. Though recorded only decades later as The Five Gates of Daoxin, his influence shaped the foundation for what would become the East Mountain Teaching.

Among Daoxin’s disciples was Niutou Farong (594–657), who established the Ox-Head school of Chan.

This branch took root on Mount Niutou in present-day Jiangsu and emphasized the illusory nature of objective reality. Farong’s Xin Ming, or Song of the Mind, expanded on the Chan view that all phenomena are projections of consciousness, and that true seeing requires the dissolution of ego and concept.

(Read the Xin Ming)

(Alternate translation)

Though the Ox-Head school was not accepted as part of the orthodox lineage, it flourished into the eighth century before eventually fading during the Song. Its texts, however, continued to influence later developments in both Chan and Seon (Korean Zen).

The Fifth Patriarch, Daman Hongren (601–674), continued Daoxin’s vision of a settled Chan community.

At the East Mountain temple in Huangmei, he refined the balance between meditation and monastic discipline. Under his guidance, Chan began to attract students from a wider range of society—scholars, aristocrats, and wandering seekers alike. One of his students, Shenxiu, became the most prominent teacher of his generation, even receiving imperial patronage.

But it was another student—unknown at first—who would eventually shape the future of Chan.

This was Huineng, a layman from the south, poor and illiterate, whose life would become legend.

His emergence as the Sixth Patriarch would mark a dramatic turning point, not only in the lineage, but in the entire character of Chan itself.

East Mountain Teaching

With the Fifth Patriarch, Daman Hongren (601–674), the Chan tradition began to settle.

Hongren had trained from childhood under Dayi Daoxin, and after Daoxin’s passing, he succeeded him as abbot. He moved the community to Mount Pingmu, the eastern peak of the Shuangfeng range in what is now Anhui Province. From this new location, the East Mountain School (Dongshan Famen) took shape.

At East Mountain Temple, the balance of monastic structure and meditative practice deepened.

Hongren emphasized quiet cultivation of the mind, grounded in the teachings of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, the Prajñāpāramitā scriptures—including the Diamond Sutra and Heart Sutra—and the influential treatise Awakening of Faith in the Mahāyāna.

Though traditionally attributed to the Indian poet Aśvaghoṣa, the Awakening of Faith was likely composed by Paramārtha or a Chinese scholar in the sixth century. It articulated the idea that all phenomena arise from the One Mind, the luminous source beyond duality.

Hongren’s approach emphasized meditation on emptiness, stillness, or a chosen object of concentration—what he referred to as an “ultimate principle.” The goal was samādhi: single-pointed absorption in the mind’s true nature. His collected teachings, later compiled as the Treatise on the Essentials of Cultivating the Mind, formed one of the first attempts to express Chan practice in systematic terms.

(Read more on Hongren’s teachings)

Hongren passed the robe and bowl to Huineng (638–713), a layman from the south, designating him as the Sixth Patriarch. But another student, Yuquan Shenxiu (606–706), also became a prominent figure and was later recognized by the imperial court.

It was Shenxiu who first used the term “East Mountain Teaching” to describe the lineage of Daoxin and Hongren.

A scholarly and refined monk, Shenxiu developed a strong following. He was invited to the capital at Luoyang by Empress Wu Zetian, who is said to have bowed to him in reverence. Shenxiu later taught Chan between the two imperial capitals of Luoyang and Chang’an (present-day Xi’an), helping transform the once-obscure mountain school into a respected religion at the heart of courtly life.

Despite his prominence, Shenxiu’s role in the formal lineage is contested.

Though widely honored during his lifetime, he was not named a patriarch in traditional Chan transmission records. The historical succession of the Dharma had passed to Huineng. The later division of Chan into the Northern School, associated with Shenxiu, and the Southern School, associated with Huineng, would grow into a lasting tension—partly literary, partly political.

Another of Hongren’s students, Faru (638–689), also played a major role in spreading Chan beyond the East Mountain community.

Faru taught at the Shaolin Monastery and developed a large following in northern China. Though he never achieved formal recognition as a patriarch, his teachings helped popularize Chan in both Luoyang and Chang’an. After his death, Shenxiu became the leading Chan figure in the North.

In this way, the East Mountain Teaching became a bridge.

It preserved the quiet cultivation of the early patriarchs while also preparing the way for Chan’s entrance into public life. As the tradition spread to cities and courts, it began to diversify. The question of succession—and the meaning of enlightenment itself—would soon erupt in one of Chan’s most famous turning points.

Huineng, the Sixth Patriarch

Huineng (638–713) stands as a pivotal figure in the history of Chan Buddhism.

Revered as the Sixth Patriarch and founder of what came to be called the Southern School, his life and teaching are preserved in one of the most influential texts of the Chan tradition: The Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch. Though attributed to his disciple Fahai, the text was likely composed and expanded well into the eighth century, with strong editorial influence from Heze Shenhui, Huineng’s Dharma heir and political advocate.

The Platform Sutra begins not with doctrine, but with a story—a moment of insight rooted in poverty and simplicity.

According to the narrative, Huineng was born in Guangdong. After his father lost his position and died, Huineng and his mother lived in hardship. He earned a living chopping and selling firewood. One day, while delivering wood to a shop, he overheard a layman reciting a line from the Diamond Sutra. In that moment, Huineng awakened.

He asked the layman what scripture it was and where he had heard it. The man told him of the Fifth Patriarch, Hongren, who taught at the Eastern Mountain monastery in Huangmei, Hubei Province. Huineng set out at once.

At the monastery, he requested an audience with Hongren and told him, “I seek only to become a Buddha.”

The abbot, noting his southern accent and humble background, questioned his origins. Huineng replied that while people may be from north or south, there is no north or south in Buddha-nature. Impressed, Hongren allowed him to stay, but assigned him to menial work—pounding rice and splitting firewood—to avoid stirring resentment among the more learned monks.

It is here that The Platform Sutra presents the now-famous contest of verses.

When Hongren sensed his own death approaching, he asked the monks to compose a verse expressing their understanding of the Dharma. Shenxiu, the most senior disciple, submitted a verse suggesting gradual cultivation of mind through continuous effort.

Huineng, still a servant in the background, responded with a verse stating that the mind is already pure, needing no polishing. Though the story’s historicity is uncertain, the verses became literary symbols of two styles of practice: one gradual, the other sudden.

Shenhui (684–758), Huineng’s later successor, used this narrative to draw a sharp division between what he called the “gradualist” Northern School, led by Shenxiu, and the “sudden enlightenment” Southern School, descending from Huineng.

He claimed that true insight was immediate, not acquired through progressive effort. This framing would define much of the rhetoric of later Chan, though it may owe more to sectarian rivalry than historical reality.

Modern scholars have questioned the sharpness of this division.

Shenxiu himself may not have advocated a purely gradualist view, and it is likely that both Northern and Southern teachings included elements of both approaches. Shenhui’s intent, some argue, was not to clarify doctrine but to legitimize his own lineage and gain influence at court. He recast Huineng as the rightful heir of the patriarchal line, elevating the Diamond Sutra as the true text of Chan, in contrast to the earlier emphasis on the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra.

Whether historical or embellished, the story of Huineng became central to the Chan tradition.

It affirmed the possibility of awakening outside conventional education, ritual, or status. And it placed at the center of Chan a profound trust in the mind’s innate clarity—waiting not to be built, but uncovered.

The Mind-Verse Contest and the Transmission of the Dharma

The turning point in Huineng’s story—and in the shaping of Chan Buddhism—unfolds with a poem.

When the Fifth Patriarch Hongren felt his time drawing near, he devised a way to determine his Dharma heir. He asked the monks of his community to compose a verse that expressed their insight into wisdom (prajñā). This, he said, would reveal who had truly seen into the nature of mind.

All eyes turned to Shenxiu, the senior monk. He was revered for his learning, discipline, and presence, and it was widely assumed he would inherit the lineage. As a result, none of the other monks dared to write. But Shenxiu, though confident in appearance, was inwardly unsure. For four days, he tried and failed thirteen times to compose a suitable stanza.

Finally, under the cover of night, he wrote a verse anonymously on a corridor wall:

The body is the bodhi tree,

The mind a mirror bright.

Constantly strive to keep it clean,

And let no dust alight.

When Hongren saw the verse the next morning, he acknowledged it respectfully but not enthusiastically.

He ordered incense to be lit before it and instructed the monks to recite it, but in private he told Shenxiu that the verse, while commendable, did not reflect complete understanding. He urged him to contemplate further and try again.

Word of the verse spread throughout the monastery.

One day, Huineng, who had been working quietly in the rice-hulling shed, heard a young monk reciting it aloud. Curious, he asked to be shown the poem, but since Huineng was illiterate, he asked a passing officer to read it to him. After hearing it, Huineng asked the man to write down his own verse in response:

There is no bodhi tree,

Nor stand with mirror bright.

Since all is empty from the start,

Where can the dust alight?

This verse directly challenged the framework of gradual cultivation.

Where Shenxiu implied effort, discipline, and ongoing purification, Huineng pointed to the empty, original nature of mind—needing neither polishing nor perfection.

Those gathered around the poem murmured in amazement. How could someone pounding rice speak so clearly of the Way? They began to question appearances and hierarchy. But Hongren, fearing jealousy and discord, quickly smudged Huineng’s verse with his shoe and told the crowd it showed no true insight. The monks dispersed.

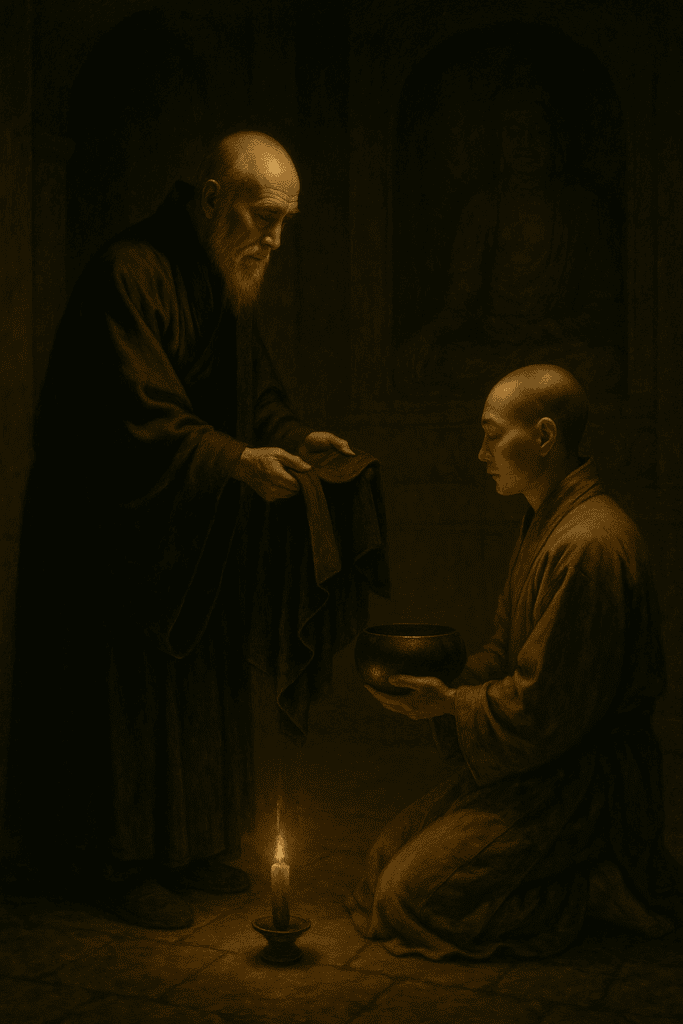

That night, Hongren quietly summoned Huineng to his quarters.

There, in the dark stillness of the monastery, he recited a passage from the Diamond Sutra. When he came to the line, “Let the mind arise without attaching to anything,” Huineng was suddenly awakened. He exclaimed that the essence of mind is pure, changeless, eternal, and the source of all manifestations.

Hongren recognized the depth of his insight.

He confirmed Huineng’s enlightenment and transmitted to him the Dharma. Along with the teaching, he gave Huineng the robe and bowl of Bodhidharma—the symbols of patriarchal succession.

Yet with transmission came danger. Hongren warned Huineng that jealousy could turn to violence.

He advised him to flee the monastery and live in hiding until the time was right to teach. Huineng obeyed. He departed into the night, carrying the Dharma in silence, trekking south through the forests, passing as a layperson, remaining unknown for years.

This is where the legend leaves the monastery and enters the realm of contested memory.

Much of what we know of Huineng comes from the Platform Sutra—a text composed decades later, likely under the editorial hand of his successor, Heze Shenhui.

Shenhui publicly attacked Shenxiu’s disciples, casting the Northern School as gradualist and unawakened, and claimed for Huineng the title of true Sixth Patriarch. He reframed the Diamond Sutra as the central scripture of the lineage, replacing the earlier prominence of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra.

Modern scholarship raises serious doubts about the historicity of these events.

Some researchers suggest that Shenhui exaggerated or even invented aspects of Huineng’s story to establish himself as the heir to a single, pure line of transmission.

As far as can be determined, Huineng was known during his life mainly in southern China, and regarded by some as a regional teacher. Yet over time, his reputation grew, and with it the influence of the Southern School.

Today, a mummified body said to be that of Huineng rests in Nanhua Temple in Shaoguan, Guangdong.

It was seen by the Jesuit Matteo Ricci in 1589. Whether legend or history, the story of Huineng lives on—not just as a tale of succession, but as a poetic reminder that enlightenment may come not through status, study, or privilege, but through sudden recognition of what has always been.

The Platform Sutra and the Doctrine of Sudden Enlightenment

The Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch is not a conventional sutra.

It is not a discourse of the historical Buddha, but a collection of teachings, stories, and dialogues attributed to Huineng, compiled and shaped over decades by his disciples—especially Heze Shenhui. Yet despite its uncertain authorship, the Platform Sutra has become one of the most important texts in the Chan tradition, and one of the most distinctive works in all of East Asian Buddhism.

It opens with Huineng’s autobiography, delivered, according to legend, in a public address at Dafan Temple before an assembly of monks, nuns, Confucian scholars, Daoist priests, and laypeople.

His words are presented not as formal doctrine but as living insight.

He tells the story of his awakening—not through scholarship or ritual, but through hearing a single line of the Diamond Sutra, working in a monastery kitchen, and composing a verse that overturned all prior understanding.

The heart of the Platform Sutra lies in its emphasis on sudden enlightenment.

Huineng teaches that awakening is not a distant goal, achieved through gradual purification, but an immediate realization of the mind’s inherent nature. “Originally there is not a single thing,” he says. “Where can dust alight?” This phrase, echoing his verse in the succession story, becomes a refrain for the whole text.

For Huineng, wisdom (prajñā) is not something added to the mind, but something revealed when delusion is dropped.

The Platform Sutra rejects the idea that awakening requires the accumulation of merit, intellectual study, or the slow climbing of spiritual stages. Instead, it declares that Buddha-nature is already present, and that enlightenment is simply the direct recognition of this truth.

This doctrine of sudden enlightenment (dunwu) stood in sharp contrast to the so-called gradualist view attributed to Shenxiu and the Northern School.

Yet as scholars now note, the differences may not have been so stark in practice. Both approaches valued meditation, morality, and insight. The sharp division may have been emphasized more by Shenhui for political and sectarian purposes than by the actual teachings of the two schools.

Nevertheless, the rhetoric of sudden enlightenment gave Chan a new voice.

It allowed for a Buddhism that did not rely on temple hierarchy, education, or textual knowledge. A firewood cutter could become a patriarch. A moment of hearing a sutra could be enough to awaken the Way. This was a powerful message—especially in a time when Buddhism was growing among laypeople, artisans, and rural communities.

The Platform Sutra also reflects a broader integration of Buddhist and Chinese thought.

Its language echoes Daoist concepts of wu wei (non-action) and the Confucian ideal of innate moral clarity. It speaks not only of non-duality, but also of compassion, precepts, and appropriate conduct. In this way, it serves as both a philosophical treatise and a practical guide.

Over time, the Platform Sutra became a cornerstone of Chan literature.

It was recited, studied, and copied in monasteries across southern China. In later centuries, it would be transmitted to Korea and Japan, where its influence continued in the teachings of Seon and Zen.

Though born in controversy and shaped by legend, the Platform Sutra remains a testament to a profound truth:

The mind, as it is, holds the path. Nothing needs to be added. Enlightenment is not elsewhere—it is already here, in this very moment, waiting to be seen.

Huineng’s Legacy and the Rise of the Five Houses of Chan

Huineng passed away in 713 CE at Nanhua Temple in Shaozhou, in what is now northern Guangdong.

Though his life was lived largely in obscurity, his legacy would shape the entire future of Chan Buddhism. With him, the heart of the tradition shifted—geographically, philosophically, and culturally—from the mountains of central China to the diverse and open frontier of the south.

Following Huineng’s death, the Chan lineage continued through a series of remarkable disciples. Among them were Nanyue Huairang and Qingyuan Xingsi, both of whom would become the root teachers of what later came to be called the Five Houses of Chan.

These houses—Weiyang, Linji, Caodong, Fayan, and Yunmen—did not arise immediately, but grew organically over the next two centuries, taking root in different regions and developing distinctive styles of practice and teaching.

The common thread across these lineages was the emphasis on direct experience, non-conceptual insight, and the transmission of awakening from teacher to student.

But each house also cultivated its own tone. The Weiyang school was methodical and analytical. Linji was bold, sudden, and filled with shouts and blows. Caodong emphasized silent illumination. Fayan wove metaphor and philosophy into its style. Yunmen relied on terse, poetic phrases—sometimes a single word.

What unified them was Huineng’s foundational principle: that awakening is already present.

Each school expressed this principle differently, but all looked back to the Sixth Patriarch as the true root of their tradition. His image—poor, uneducated, awakened through a single phrase—served as a perpetual reminder that wisdom is not the product of study or ritual, but of insight into the nature of mind.

By the ninth century, the rhetoric of sudden enlightenment had become the norm.

Even those who taught gradual cultivation acknowledged that realization itself was always immediate. The debates between Northern and Southern schools faded. Chan was no longer a sectarian movement but had become the dominant form of Chinese Buddhism.

The influence of Huineng extended beyond philosophy.

His legacy shaped monastic life, language, poetry, and even politics. Chan monasteries adopted forms of communal labor and meditation that echoed his simple beginnings. The Platform Sutra became a foundational text, not only for monks, but also for laypeople seeking a direct path.

In the centuries to follow, Chan would travel beyond China—into Korea as Seon, into Japan as Zen, and into Vietnam as Thiền. But the heart of its teaching remained the same:

The Way is not found by reaching, but by seeing. And that seeing begins not in temples or texts, but in the stillness of one’s own mind.

Tang Dynasty Chan Masters and the Five Houses

The Tang dynasty (618–907) was a golden age for Chinese civilization—a time of cosmopolitan culture, flourishing poetry, and religious diversity.

It was also the period in which Chan Buddhism came fully into its own. From the roots planted by Huineng and his disciples, new branches emerged, spreading widely across China. The teachings became bolder, more poetic, and more enigmatic. By the end of the Tang, the Chan tradition had diversified into what became known as the Five Houses.

These lineages were not political institutions, but living lineages of practice and realization, each centered on a master whose distinctive teaching style left a mark on the Dharma. The Five Houses were:

- Weiyang (Guiyang) – founded by Guishan Lingyou and his disciple Yangshan Huiji

- Linji (Rinzai in Japan) – founded by Linji Yixuan

- Caodong (Sōtō in Japan) – founded by Dongshan Liangjie and his student Caoshan Benji

- Fayan – founded by Fayan Wenyi

- Yunmen (Ummon in Japan) – founded by Yunmen Wenyan

Each of these schools shared the same essence: direct pointing to the mind, and a reliance on personal transmission over doctrinal formulation.

Yet each developed a distinct voice.

The Weiyang school emphasized careful dialogue and structured inquiry.

It was contemplative and methodical, seeking to clarify the subtle workings of the mind through reasoned teaching and metaphor. Though it flourished in the Tang, it eventually declined and was absorbed into later schools.

The Linji school, by contrast, was forceful and immediate.

Linji Yixuan (d. 866) became known for his unpredictable teaching style—shouting, striking, and sudden paradoxical remarks that broke through conceptual thinking. His dialogues, recorded in the Linji Lu (Record of Linji), became central texts in later Chan and Zen. His approach emphasized boldness, spontaneity, and the ability to awaken in the midst of confusion.

The Caodong school, founded by Dongshan Liangjie and Caoshan Benji, focused on “silent illumination” (mozhao).

Rather than dramatic encounters, it emphasized gentle introspection and subtle awareness. The practice of seated meditation (zuochan) was cultivated not as a method to reach enlightenment, but as an expression of it. This school would later flourish in Japan as Sōtō Zen.

The Fayan school combined eloquence and philosophical reflection.

Fayan Wenyi encouraged his students to examine the dynamics of language and meaning, using subtle distinctions to point toward the nature of mind. His school attracted many scholar-monks and bridged the gap between Chan and classical Buddhist philosophy.

The Yunmen school, led by Yunmen Wenyan, was terse and poetic.

Yunmen was known for delivering a single word or short phrase that carried layers of meaning—such as “barrier,” “dry shit stick,” or simply “yes.” His words, though brief, were meant to stop the mind and open the eye.

The Five Houses arose from different regions and temperaments, yet all traced their lineage to Huineng.

They differed in form, but not in essence. All held that the nature of mind is originally pure, and that awakening is not found in scriptures or effort alone, but through direct experience.

By the late Tang, Chan had become the most dynamic force in Chinese Buddhism.

Its monasteries grew in number, its texts were copied and preserved, and its masters were sought by emperors and commoners alike. Yet it retained something of its early character—plain robes, simple meals, and sudden insight.

The Five Houses would shape the next thousand years of Buddhist practice, not only in China but across East Asia. They were not schools of doctrine, but schools of living wisdom—each one a different doorway into the same empty, luminous mind.

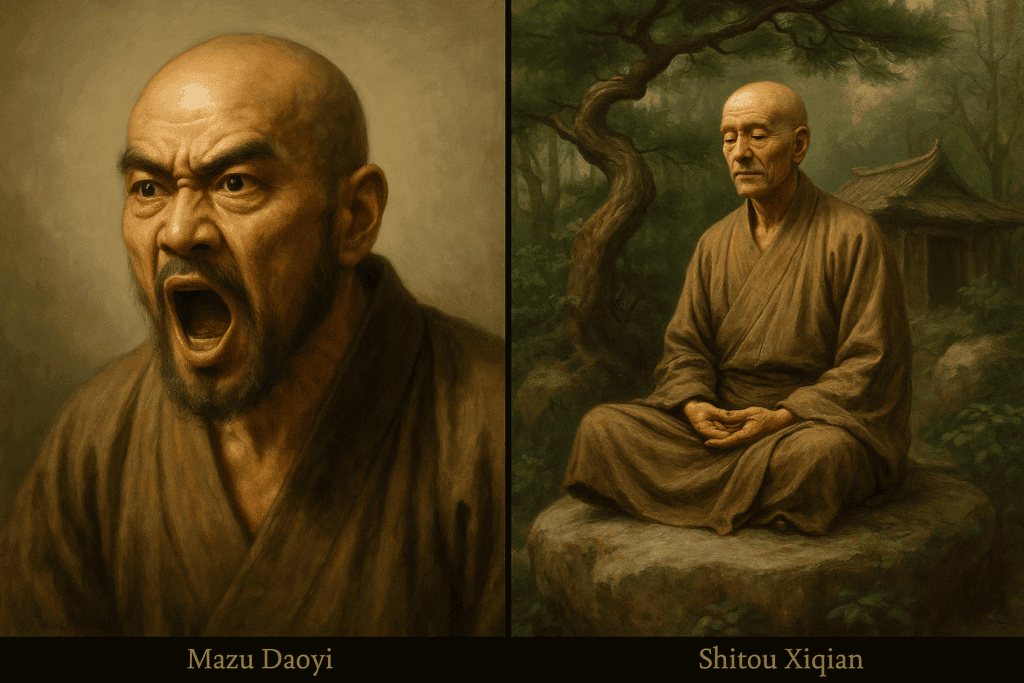

Mazu Daoyi and Shitou Xiqian

As Chan Buddhism matured during the Tang dynasty, two towering figures emerged whose teachings would shape the future of the tradition in distinct and enduring ways.

Mazu Daoyi and Shitou Xiqian, contemporaries and Dharma brothers in the extended lineage of Huineng, became the fountainheads from which nearly all later schools of Zen would eventually flow.

Mazu Daoyi (709–788), known as Master Ma, is often regarded as the most influential teacher in the history of early Chan.

He was the leading figure of the Hongzhou school, which came to represent what later generations would call the “golden age” of Chan. Under Mazu’s guidance, Chan moved decisively away from scholasticism and into a bold, spontaneous, and iconoclastic mode of transmission. It was during his time that the phrase “Chan school” (Chan zong) was first recorded, in a collection of his sayings known as the Extensive Records.

Mazu’s teaching style became legendary: “strange words and extraordinary actions” were used to shock students out of conceptual thought.

He employed shouting, sudden blows, and seemingly irrational statements—not to confuse, but to awaken. His famous kōan “What the mind is, what the Buddha is” brought one of his disciples, Damei Fachang, to a sudden realization. Later, Mazu would contradict the same phrase with a new one: “No mind, no Buddha.” He was not contradicting truth, but undermining fixation—pointing beyond both attachment and detachment.

Zhaozhou Congshen (Joshu, 778–897) was one of the most revered and enigmatic masters of Chinese Chán (Zen) Buddhism. A student of Mazu, Zhaozhou is celebrated for his subtle, paradoxical teachings and his profound embodiment of awakened presence. Living during the Tang dynasty, Zhaozhou is best known through his frequent appearance in classical Zen kōan collections, including the Mumonkan (Gateless Gate) and the Blue Cliff Record.

His teaching style, marked by simple yet piercing words—such as his iconic response “Mu” (“no”) to a question about a dog’s Buddha-nature—continues to challenge and illuminate students of Zen across centuries. Zhaozhou emphasized everyday mindfulness and often rejected complex doctrinal discussions in favor of direct, unadorned insight into the nature of mind. His long teaching career, marked by humility, gentleness, and unwavering clarity, left an enduring imprint on the Chán tradition and helped shape the spontaneous, intuitive character of East Asian Zen.

Shitou Xiqian (700–790), though quieter in temperament, was no less foundational.

He became a novice under Huineng shortly before the patriarch’s death, and later studied under Qingyuan Xingsi, who is said to have transmitted the Dharma to him. While historical details of this lineage are debated—Qingyuan’s existence may have been retroactively constructed during the Song to legitimize Shitou’s succession—the influence of Shitou’s teaching is indisputable.

Shitou lived much of his life in hermitage.

He taught from a simple monastery on Mt. Nanyue in Hunan Province, dwelling atop a large boulder, which gave him the name “Shitou”—Stone-Head. From his lineage came three of the Five Houses: Caodong, Yunmen, and Fayan.

Unlike the confrontational methods of the Hongzhou school, Shitou’s style was meditative, poetic, and integrative.

He is credited with composing two of the most beloved and philosophically rich texts in the Chan literary tradition. The Sandokai (Harmony of Difference and Equality) explores the interplay of absolute and relative truth, affirming the non-duality of form and emptiness. The Song of the Grass Hut offers a contemplative vision of the ideal monastic life—solitary, simple, and rooted in the mind’s quiet clarity.

Mazu and Shitou represent two complementary currents within Tang dynasty Chan.

Mazu’s dramatic style emphasized breakthrough, challenging students with sudden gestures. Shitou’s teaching unfolded more gently, pointing to the unity of opposites and the cultivation of inner balance. Together, they offered a full spectrum of Chan experience—shock and silence, action and repose.

All existing branches of Zen trace their lineage back to one of these two figures.

From Mazu came the Linji school, with its sharp cries and irreverent dialogues. From Shitou came the Caodong school, known for its silent illumination. Their influence stretches across centuries and cultures—from Tang dynasty China to modern Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and beyond.

They did not seek to create schools. They taught what they saw.

And in doing so, they helped shape a living tradition that continues to ask the same quiet question: What is this mind, right here and now?

Chan Monastic Codes and Meditation Practice

Long before the rise of Chan, Chinese Buddhist communities had already cultivated a disciplined and orderly monastic life.

One of the earliest and most influential figures in this development was the monk Daoan (312–385). Known for his translations and commentaries, Daoan also helped shape the structure of the Chinese sangha. His now-lost Standards for the Clergy and Charter for Buddhism laid the groundwork for monastic discipline in China, influencing generations to come.

Daoan’s legacy continued through later luminaries.

He shaped the thinking of the great translator Kumārajīva and influenced Daoxuan (596–667), a central figure in the Lü Vinaya school. Daoxuan compiled the Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks, a key text combining historical record with normative guidance.

He studied and commented on multiple vinaya systems, including the Ten Recitation Vinaya of the Sarvāstivāda school and the Four-Part Vinaya (Sìfēn Lǜ) of the Dharmaguptaka school—still the foundation of monastic conduct in Chan and Zen communities today.

By the early fifth century, other vinayas such as the Five-Part Vinaya of the Mahīśāsaka school and the Kāśyapīya Vinaya were translated into Chinese.

Though Daoxuan noted that the Pudgalavāda vinaya was known, it had not yet been rendered into Chinese. Meanwhile, Zhiyi (538–597), the founder of the Tiantai school, proposed a schedule of four daily meditation periods in his Rules in Ten Clauses. This emphasis on seated practice would carry into later Chan and Zen monastic life.

The Chan tradition inherited these foundations, but gradually shaped them to suit its unique spirit.

As Chan developed during the Tang dynasty, a new mode of monastic regulation emerged—guided not only by vinaya, but by the rhythm and ethos of Chan practice itself.

This key moment in the evolution of Chan institutional life with Baizhang Huaihai (720–814), Dharma heir of Mazu Daoyi and teacher of Huángbò Xīyùn, who would go on to teach Linji Yixuan, founder of the Linji (Rinzai) school.

Baizhang is traditionally credited with formulating the first comprehensive Chan monastic code, known as the Pure Rules of Baizhang. While no complete version of the original survives, later texts quoted and elaborated on it. The rule emphasized simplicity, communal labor, and autonomy, famously encapsulated in the phrase: “A day without work is a day without food.”

This rule is considered the first true sinicization of the Indian vinaya—melding Indian ethical discipline with Chinese self-sufficiency and pragmatism.

Yet modern scholars question whether Baizhang’s rules constituted a radical departure from earlier tradition. His disciple Guishan Lingyou (771–853), founder of the Guiyang school, authored the Admonitions of Guishan, which reveal that Chan remained firmly grounded in established Buddhist norms. This continuity is echoed in the earliest extant Chan code, the Teacher’s Regulations (Shi guizhi), compiled by Xuefeng Yicun (822–908) in 901.

Later codes expanded upon Baizhang’s legacy.

The Rule of the Chan Gate (Chanmen guishi), composed in the ninth or tenth century, presented itself as a synopsis of Baizhang’s teachings. This was included in the Record of the Transmission of the Lamp (1004) alongside Baizhang’s biography, and reappeared in the Chanyuan Qinggui of 1103 as a commentary. A preface was even added in the Imperial Edition of the Baizhang Code published in 1336 under the Yuan dynasty.

The most comprehensive and influential of all Chan codes was the Chanyuan Qinggui—The Rules of Purity in the Chan Monastery—compiled by Changlu Zongze in 1103.

Also known as The Monastic Regulations of the Zen Garden, it became the standard for Chan and Zen communities alike. Covering everything from robe-folding to etiquette in the meditation hall, this code also codified formal periods of seated meditation within the daily schedule.

By the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279), Chan monasteries regularly held four daily meditation sessions—at dawn, dusk, late evening, and midnight.

These came to be known as the “four hours,” and were practiced in both Chinese and Japanese monasteries until the fourteenth century, when the schedule was typically reduced to three sessions per day. In addition to daily practice, monks gathered for intensive meditation during weekly, monthly, and annual retreats.

These retreats echoed an ancient precedent.

From the time of the historical Buddha, Indian monks had paused their travels during the rainy season for a three-month retreat, observing the vinaya rule that forbade movement during this time. This practice, preserved in China, became the model for extended periods of meditation and introspection in the Chan tradition.

The tradition would later travel to Japan, where it was adopted by Soto Zen as the Ango retreat—meaning “peaceful dwelling.”

Since the time of Dōgen, Ango has been a required part of Soto Zen monastic training. Today, it remains one of the most intensive expressions of collective practice. While meditation (dhyāna, or chan) can be practiced alone, the monastery—held together by the bonds of ethics (śīla) and rhythm—is its ideal environment.

From Daoan to Zongze, Chan monasticism walked a path between tradition and transformation.

Though it celebrated spontaneity and awakening beyond words, Chan monastic life was grounded in discipline, refinement, and daily order. In the silence of the meditation hall—framed by structure and supported by rule—the sudden could arise.

Han Shan: The Laughing Hermit of Cold Mountain

Han Shan (“Cold Mountain”) was a legendary Chinese poet and recluse, traditionally believed to have lived during the Tang dynasty (7th–9th centuries CE). His true identity remains shrouded in mystery—some scholars believe he was a monk, others a wandering hermit or a scholar who rejected worldly life.

Living alone in the remote mountains of Tiantai in southeastern China, Han Shan wrote hundreds of poems carved onto rocks, trees, and temple walls. His verses, filled with humor, melancholy, spiritual insight, and rustic imagery, form a unique body of literature known as the Cold Mountain Poems.

Han Shan’s work blends Chan (Zen) Buddhist thought with Daoist themes of natural simplicity and detachment. His poetry often mocks human ambition, questions religious institutions, and finds profound joy and freedom in solitude.

Today, Han Shan is revered not only in Chinese tradition but also in Japanese Zen and modern world literature, where he is seen as an archetype of the enlightened outsider: laughing, wandering, and free.

Han Shan’s poetry is rich with alchemical imagery, blending Daoist and Chan metaphors for inner transformation. Han Shan’s poems use Daoist and Chan imagery to depict the natural alchemy of awakening beyond rituals or formulas. Here are a couple of fitting examples of Han Shan poems with alchemical undertones:

Men ask the way to Cold Mountain,

but the road does not go through the clouds.

Summer melts the magic herbs;

the seasons change, and the white elixir flows.

In the streams, the moon shines pure;

in the pines, the wind’s a voice.

Who knows the formula to escape the dust?

Sit quietly, and see yourself become stone.

(Adapted from translations by Burton Watson and Red Pine.)

Quick Notes on the Alchemical References:

- “Magic herbs” and “white elixir” reference Daoist internal alchemy, where herbs symbolize spiritual ingredients and white elixir often refers to the pure energy or refined spirit (sometimes associated with the “Golden Elixir” of immortality).

- “Escape the dust” is a Chan/Daoist phrase meaning to transcend the mundane world of birth, death, and delusion.

- “Become stone” evokes both Chan stillness and Daoist ideas of spiritual transmutation: attaining the immutable, enduring essence.

Here is a second example — a slightly wilder and more humorous Han Shan poem that still carries alchemical transformation imagery:

Once I was a crazy fool,

chasing gold and titles, wearing out my bones.

Then I stumbled on Cold Mountain’s road

and found my way to the Elixir Spring.

Now I sit in the grass, making nothing of the world—

the tiger growls, the dragon soars inside me.

Without forging iron, without heating mercury,

I melted my mind into pure light.

(Adapted from Red Pine’s and Gary Snyder’s translations of Han Shan.)

Quick Notes on This Poem:

- “Elixir Spring” — Symbolic of finding the natural source of spiritual immortality, not through external alchemy but through inner awakening.

- “Tiger growls, dragon soars” — Classic Daoist imagery: the tiger and dragon represent yin and yang energies dynamically interacting inside the alchemist (or meditator).

- “Without forging iron, without heating mercury” — Direct mockery of literalist Daoist alchemy practices; true transformation happens internally without laboratory work.

- “Melted my mind into pure light” — A clear metaphor for realization or enlightenment beyond physical form.

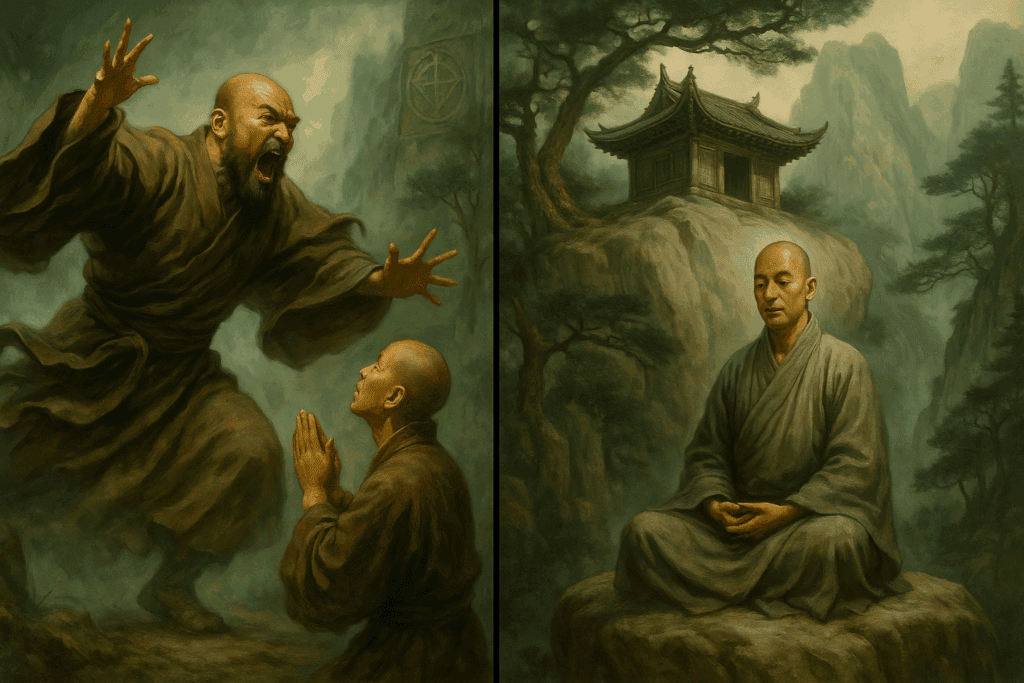

Linji and Xuefeng

By the ninth century, Chan Buddhism had matured into a multifaceted tradition. Among its most iconic figures was Linji Yixuan (d. 866), whose uncompromising style gave rise to one of the most enduring branches of Chan: the Linji school—known in Japan as Rinzai Zen.

Linji was a Dharma heir of Huangbo Xiyun, a key disciple of Baizhang Huaihai.

According to the Zutang ji (952), Linji attained awakening not directly through his teacher, but while discussing Huangbo’s teachings with a reclusive monk named Dayu. After this encounter, he returned to Huangbo to deepen his training. In 851, Linji settled at a temple in Hebei Province. It was from this location—Linji Temple—that his name, and the name of the school, would be derived.

Linji’s words are preserved in the Línjì yǔlù—The Record of Linji—a collection of sermons, dialogues, and exhortations compiled posthumously.

Though the standard version of the text was not finalized until the Song dynasty—more than two centuries after Linji’s death—it captures the spirit of the Hongzhou school founded by Mazu Daoyi, transmitted through Huangbo. Like his predecessors, Linji rejected reliance on scriptures, rituals, and intellectual formulations. His language was fierce, startling, and uncompromising. He used shouts (katsu), strikes, and paradoxical phrases to jolt students out of conceptual thinking.

He urged disciples to “kill the Buddha” and to avoid clinging to any image of enlightenment.

“Don’t look for the Buddha,” he said. “The Buddha is you.” For Linji, realization could not be taught—only provoked. The path was not a gradual ascent, but a sudden seeing into one’s own nature, unmediated by doctrine or expectation.

Chan in Linji’s time struggled with how to express “suchness”—the pure, ungraspable nature of reality—without becoming ensnared in words.

Linji’s radical gestures were not mere theater; they were expressions of this dilemma. Words were tools, but dangerous ones. If misunderstood, they turned into traps. Linji’s voice, sharp and raw, broke through those traps.

Although Linji’s school was not widely recognized during his lifetime, it rose to prominence in the centuries that followed.

Over the Song dynasty (960–1279), the Guiyang, Fayan, and Yunmen schools were gradually absorbed into the Linji lineage. The Linji school of Dahui Zonggao, known for reviving koan practice, became dominant and gained patronage from the imperial court. In time, Linji’s method became the face of public Chan in East Asia, and later, of Japanese Rinzai Zen.

Yet Chan’s diversity continued, and one of Linji’s contemporaries helped shape other vital streams of the tradition.

Xuefeng Yicun (822–908) was another influential Chan master of the Tang dynasty.

Though not as confrontational in style as Linji, Xuefeng played a key role in extending Chan’s influence and institutional depth. His lineage gave rise to the Yunmen and Fayan schools—two of the Five Houses of Chan. He is also known for compiling one of the earliest extant Chan monastic codes: the Teacher’s Regulations (Shi guizhi) in 901, helping to formalize the lifestyle and expectations of the Chan monastic path.

The Zutang ji, while recording Linji’s early mention, actually presents Xuefeng’s lineage as the true heir of the Hongzhou tradition.

This suggests that Xuefeng, and not Linji, was seen in the tenth century as the more influential transmitter of Mazu’s Chan. Later tradition would reverse this perception, elevating Linji’s dramatic style as the emblem of true Chan, but in their own time, both masters contributed uniquely to the unfolding of the Way.

Together, Linji and Xuefeng embodied two dimensions of Chan’s maturity:

One, abrupt and unrelenting in its rejection of form; the other, steady and foundational, anchoring practice in the daily life of the monastery. From their teachings, monastic codes, and lineages, Chan would grow into the dominant form of Chinese Buddhism—and a living tradition still practiced today.

Dongshan Liangjie and the Caodong Lineage

As Chan matured in the late Tang period, new approaches to practice emerged—less centered on dramatic encounters, and more attuned to subtle insight and silent clarity.

Among the great figures of this period was Dongshan Liangjie (807–869), founder of the Caodong lineage of Chan Buddhism. Known for his poetic depth and refined presence, Dongshan offered a quieter path to awakening—one that would profoundly shape the development of Zen in East Asia.

Dongshan’s early life remains partly obscured by legend.

He was born in what is now modern-day Hunan or Jiangxi, and became a monk at a young age. He studied with several Chan masters, but his deepest influence came from Yunyan Tansheng, with whom he trained for years.

The records say that Dongshan experienced awakening upon hearing Yunyan’s reply to a simple question: “Who is it that hears the teachings?” Yunyan’s answer—“The one who doesn’t hear”—opened something beyond words. Later, when Dongshan crossed a river and saw his reflection in the water, he is said to have realized fully: “Do not seek the Way elsewhere—it is always right here.”

Dongshan eventually began teaching in the remote mountains of southern China.

There he founded a small monastery and attracted students who were drawn to his balanced, contemplative approach. The name of the lineage, Caodong, comes from the combination of Dongshan’s name and that of his disciple Caoshan Benji (840–901), who systematized and transmitted his master’s teachings.

Dongshan’s teachings were rooted in the stillness of direct experience.

Rather than koans or shouts, he emphasized silent illumination—a meditative awareness that did not seek to penetrate a problem, but to open to what is always already present. The Caodong school did not reject sudden enlightenment, but saw it as something unfolding naturally in the light of calm attention.

Among his best-known contributions is the poetic text “Five Ranks” (Wuwei), a set of verses that explores the dynamic relationship between the absolute and the relative, form and emptiness, light and shadow.

Each rank reflects a subtle stage of insight, but unlike step-by-step instruction, the poem reveals a shifting interplay—more like the phases of the moon than a ladder to climb. Dongshan taught that true realization lies not in transcending form, but in seeing form as itself the expression of the formless.

His other famous work, the “Song of the Jewel Mirror Samādhi,” uses metaphor and rhythm to point to the unity of opposites and the clear mirror of awareness that reflects without distortion. These poetic texts became cornerstones of the Caodong school and are still chanted and studied in Soto Zen temples today.

Though Dongshan never sought institutional power, his influence endured through his disciples and successors.

His lineage was eventually transmitted to Japan as the Sōtō school of Zen, brought by Dōgen Zenji in the thirteenth century. Dōgen, profoundly shaped by Dongshan’s teachings, would go on to develop his own expression of silent illumination, which he called shikantaza—“just sitting.”

Dongshan’s way was modest, but deep. He left no great temple, no imperial patronage, and few recorded encounters.

Yet his vision—a life of meditation, simplicity, and non-dual clarity—continues to resonate. In the soft breath of sitting, in the quiet of the early morning hall, the Caodong tradition carries forward the insight Dongshan first glimpsed in his reflection: that the Way is always here, needing only to be seen.

The Weiyang, Yunmen, and Fayan Schools

By the close of the Tang dynasty, Chan Buddhism had branched into a constellation of distinct lineages—each preserving the essence of direct insight, yet expressing it through unique forms. Among the Five Houses of Chan, the Weiyang, Yunmen, and Fayan schools stood alongside Linji and Caodong as vital currents in the living Dharma.

Weiyang: Subtle Inquiry and Gentle Precision

The Weiyang school (also known as Guiyang), the earliest of the Five Houses, was founded by Guishan Lingyou (771–853) and his Dharma heir Yangshan Huiji (807–883).

Named after their combined names—Wei from Guishan’s mountain and Yang from Yangshan—it emphasized refined dialogue, metaphoric teaching, and careful pedagogy.

Weiyang teaching was marked by structured guidance and literary elegance.

Its methods included guided contemplation, stories, and “pointing phrases” designed to invite reflection without shocking the student. It valued nuance and favored a gentle progression toward insight, as opposed to the sudden gestures of Linji-style Chan. This school emphasized harmony between master and disciple, allowing realization to unfold through close relationship and careful conversation.

While it did not become as dominant as Linji or Caodong in later centuries, the Weiyang school’s influence can be felt in the more measured and poetic elements of later Chan and Zen literature. Its voice was that of the scholar-monk in retreat: steady, luminous, and quietly transformative.

Yunmen: One Word, Total Illumination

Yunmen Wenyan (862–949), founder of the Yunmen school, brought a different energy.

A disciple in the lineage of Xuefeng Yicun, Yunmen developed a distinctive style that distilled teaching into concise, often cryptic, expressions. His dialogues were direct and paradoxical, yet compact—less explosive than Linji’s shouts, but equally penetrating.

Yunmen was known for giving single-word answers—“barrier,” “dry shit stick,” “cake”—each meant to stop the mind and open a gap in conceptual understanding.

For Yunmen, awakening was not to be argued or explained, but revealed in an instant. His teachings often feel like koans reduced to their barest core. His presence was sharp, unyielding, and immaculately clear.

Despite—or because of—this stark simplicity, the Yunmen school flourished during the Five Dynasties and early Song period.

Yunmen’s sayings are featured in key koan collections such as the Blue Cliff Record and the Gateless Gate, where their brevity only enhances their power. The Yunmen school carried the spirit of Chan as pure presence: direct, vivid, and unbound by elaboration.

Fayan: The School of Natural Expression

The Fayan school, founded by Fayan Wenyi (885–958), offered yet another tone—philosophically rich and deeply humanistic.

Also descended from the lineage of Xuefeng Yicun, Fayan’s teaching blended spontaneity with intellectual subtlety. His school emphasized “the harmony of the three teachings”—Buddhism, Confucianism, and Daoism—seeking not to reject culture and learning, but to place them in service of insight.

Fayan’s method relied on natural conversation, deep questions, and subtle shifts in perspective.

He guided students to insight not by breaking their thoughts, but by redirecting them—turning the mirror just enough to reveal what was already there. His dialogues show a master of precision and poise, aware of both context and character. In the Fayan tradition, the moment of awakening was not an interruption but a blooming.

Fayan’s school became popular among the literati and was admired for its intellectual depth and poetic voice.

It became especially influential in southern China during the Five Dynasties and early Song period, though it was eventually absorbed, along with the Yunmen and Guiyang schools, into the broader Linji lineage.

Each of these schools—Weiyang’s careful instruction, Yunmen’s piercing brevity, and Fayan’s elegant spontaneity—brought out a different aspect of the same truth:

That awakening is not a single path, but a living encounter with what is. Though only the Linji and Caodong schools would survive into later centuries, the voices of all Five Houses still echo in the texts, rituals, and meditation halls of East Asian Buddhism.

Chan Monastic and Temple Architecture and Furniture

Chan Buddhism developed not only through teachings and texts, but through space.

Its monastic architecture, temple layout, and ritual furniture reflect a sensibility grounded in simplicity, discipline, and meditative presence. Just as Chan taught that realization comes not through adornment but through clear seeing, so too its physical environments evolved to support stillness, silence, and the daily rhythm of practice.

Architectural Layout and Aesthetic

By the Tang and Song dynasties, Chan monasteries followed a basic template rooted in Indian and early Chinese Buddhist models, but with unique refinements.

A typical Chan monastery was built along a central north-south axis, aligned with cosmological and geomantic principles. Entry was through a main gate (shanmen), leading to an open courtyard and the central Buddha Hall (fo tang), where devotional images were enshrined. Behind this stood the Dharma Hall (fa tang), where lectures and public teachings were given. At the rear was the Sangha Hall (seng tang), which served as the living quarters or meditation hall for the monks.

Side buildings included the kitchen, storehouse, baths, and administrative areas, all arranged with understated symmetry.

Gardens, cloisters, and covered walkways linked the structures, creating a flow between open space and enclosure, light and shadow. The emphasis was not grandeur, but harmony. The architecture invited mindfulness—not distraction. In later Japanese Zen, this would evolve into the spare elegance of wabi-sabi, rooted in the Chan ideal of emptiness with form.

The Meditation Hall (Zendo)

The heart of the Chan monastery was the meditation hall, later called the zendo in Japanese.

Unlike earlier Buddhist temples, which emphasized image worship and chanting, the Chan hall was dedicated to silent sitting (zuochan). Long raised platforms called tan lined the hall, each covered with mats and fitted with a sitting cushion (zafu) and back pad (zabuton). Monks sat in rows facing the wall or each other, legs crossed in full or half lotus, hands in the cosmic mudra, resting in the calm of silent illumination.

During extended retreats (chansesshin), monks might sleep and eat in the hall, maintaining continuous awareness throughout. Every object in the space—cushions, robes, bowls—had its designated place and use. Precision and simplicity were themselves a form of practice.

The hall was often equipped with instruments that marked time and transitions.

A wooden fish drum (muyu) called the monks to assembly. The han board was struck in rhythmic sequence before meditation. A handbell signaled posture changes. The kyosaku, a flat wooden stick, was sometimes used by the jikijitsu (hall monitor) to gently strike a monk’s shoulders—restoring focus, not punishing.

Ritual Furniture and Symbolism

Chan ritual furniture evolved with the same aesthetic as its architecture: humble, durable, and functionally symbolic.

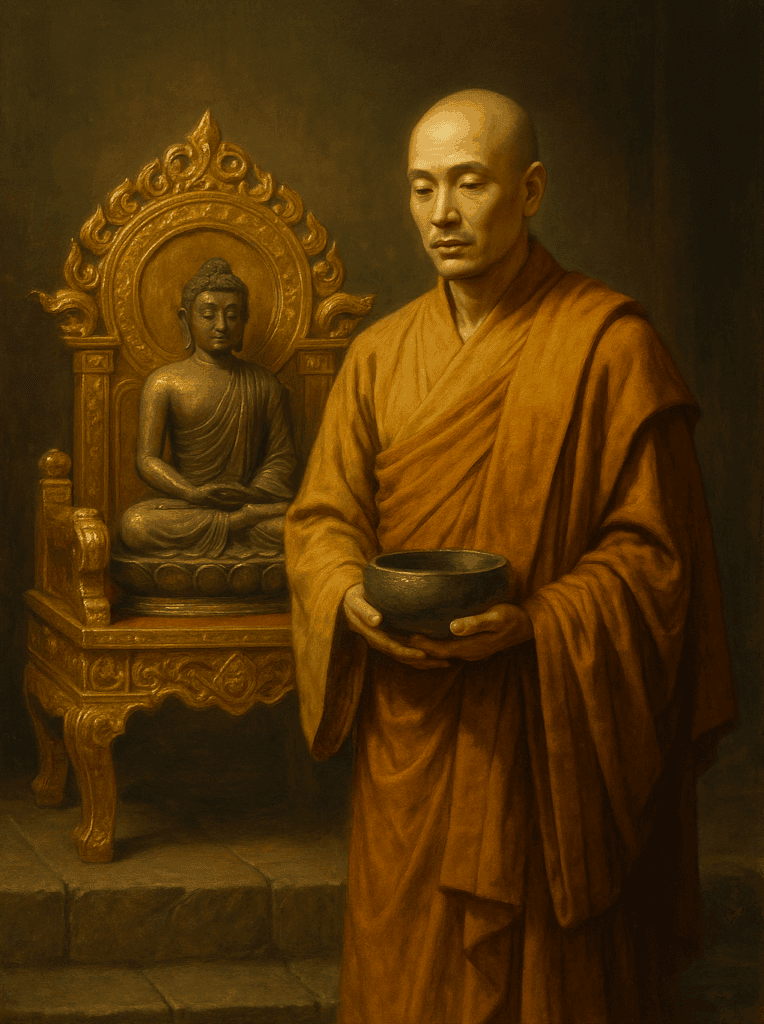

- The High Seat (Gaozuo) – In the Dharma Hall, the abbot or master taught from an elevated seat, often flanked by images of the Buddha and ancestral tablets. The high seat was not a throne, but a symbolic platform for the Dharma, raised to be heard, not to dominate.

- Incense Tables – Simple wooden stands or carved altars held incense burners, symbolizing purification and offering. The act of offering incense—quiet, reverent—marked the beginning of meditation or a Dharma talk.

- The Alms Bowl (Patra) – Though less used than in Indian mendicant traditions, the bowl remained a symbol of monastic simplicity. In Chan monasteries, meals were often taken in the oryoki style: ritualized, minimal, and silent.

- The Founder’s Hall (Zutang) – Many Chan monasteries maintained a dedicated space for honoring the ancestral lineage, particularly Bodhidharma and the Six Patriarchs. Wooden statues or inscribed tablets were installed, not for veneration, but to honor the transmission of mind.

The Space as a Teaching

Chan spaces were not neutral backgrounds for practice—they were teachings themselves.

Their stillness, structure, and emptiness embodied the very mind they pointed to. One did not need a scripture to remember the Way; a stone basin catching rainwater, or a monk sweeping leaves in silence, was enough. Function was never separate from form. Clean lines, bare walls, rhythmic walking paths—all were invitations to presence.

Over time, these aesthetic values would deeply influence East Asian culture.

In Japan, they became foundational to Zen garden design, tea ceremony architecture, and even martial arts dojos. But at their root, they expressed a truth already alive in Tang dynasty China: that space, when cultivated with care and awareness, becomes part of the path.

A Day in the Life of the Chan Monk and Nun

The life of a Chan monastic is shaped not by words but by rhythm—early mornings, silent meals, the rustle of robes, the breath in stillness.

Rooted in both Indian Buddhist discipline and Chinese practicality, the daily life of Chan monks and nuns weaves together meditation, labor, liturgy, and community in a seamless fabric of presence.

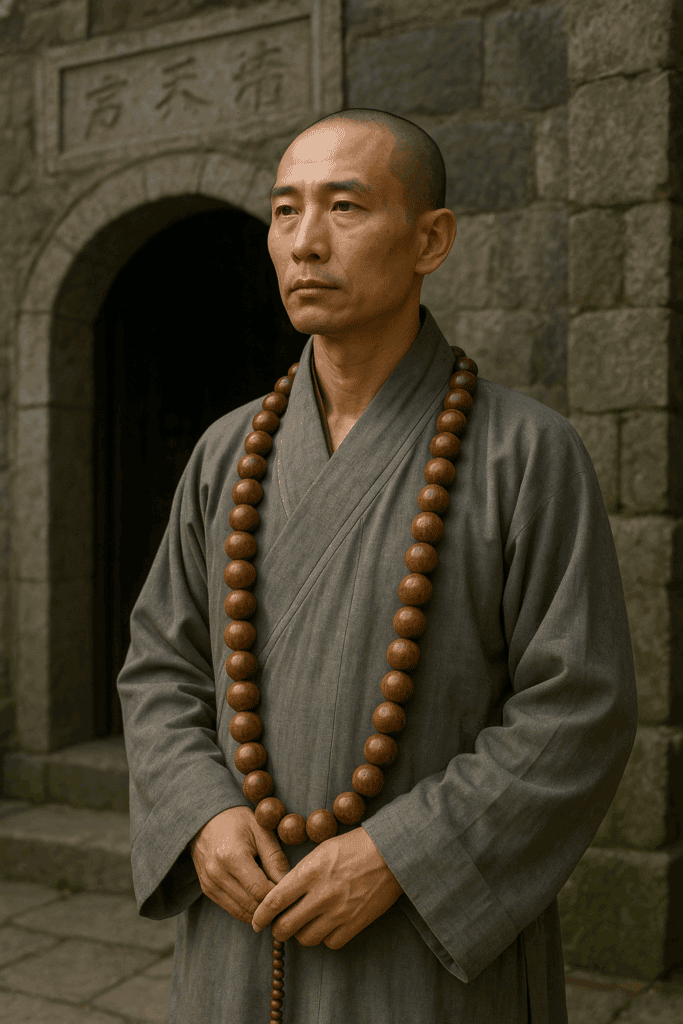

Robes and Possessions

A Chan monk or nun traditionally owns very little.

Their belongings are minimal, symbolic, and functional. The most visible of these is the monastic robe, which follows the tradition of the kasaya—a rectangular patchwork garment known in Chinese as the jiasha (袈裟). This is worn over a long inner robe (haiqing or changyi) of black or grey, colors symbolizing humility and renunciation.

The five-piece robe is worn by novices and lay followers who have taken precepts. The seven-piece robe is standard for ordained monastics. Senior monks or abbots may wear a nine-piece robe on ceremonial occasions. These robes, stitched in symbolic grids, represent the rice fields and the life of renunciation.

In addition to robes, monastics typically carry:

- A begging bowl (patra), symbolic of the Buddha’s original mendicant tradition

- A staff or walking stick, sometimes with metal rings, used in travel and ritual

- A small pouch containing personal hygiene tools, a copy of the precepts, and a hand cloth

- A zafu (sitting cushion) for meditation

- And often, a book of liturgy, chants, or Dharma sayings

Possession is deliberately minimized—not as deprivation, but as clarity. Nothing extra. Nothing to defend. Just what is needed.

Gender and Community

Nuns in the Chan tradition live parallel lives to monks, often in nearby nunneries with similar structure and discipline.

The early ordination of Buddhist nuns in China was supported by imperial patrons, and monastic codes evolved to accommodate gendered spaces without altering the core structure of practice. Nuns wore the same robes, followed the same schedules, and trained in meditation, scripture, and precepts. Their contributions, while sometimes marginalized in historical records, were essential to the flourishing of Chan as a lived tradition.

Daily Schedule

Chan monastic life is structured with remarkable precision. The day begins before dawn and ends in silence.

Typical Daily Schedule:

- 3:30–4:00 a.m. – Wake-up bell; personal hygiene and robe dressing

- 4:00–5:30 a.m. – Morning zazen (sitting meditation) in the main hall

- 5:30–6:30 a.m. – Morning chanting (Heart Sutra, Four Great Vows, ancestral names)

- 6:30–7:00 a.m. – Silent breakfast, often taken in oryoki (ritual eating) style

- 7:00–9:00 a.m. – Temple duties or manual labor (samu): sweeping, gardening, cooking, repairs

- 9:00–11:30 a.m. – Study or Dharma lectures; sometimes additional meditation

- 11:30–12:00 p.m. – Main meal of the day, again in silence and ceremony

- 12:00–2:00 p.m. – Rest period or personal practice

- 2:00–5:00 p.m. – Afternoon work period or meditation

- 5:00–6:00 p.m. – Light meal or tea (depending on precept level and tradition)

- 6:00–7:30 p.m. – Evening chanting and zazen

- 7:30–9:00 p.m. – Optional practice, self-study, or early sleep

- 9:00 p.m. – Lights out and silence

This rhythm may vary across monasteries and seasons, but the essential movement—between meditation, labor, and liturgy—remains the same. Each activity, no matter how mundane, is treated as practice.

The Liturgical Year

Though Chan de-emphasized ritual in favor of direct insight, it maintained a structured liturgical calendar.

Seasonal ceremonies marked key moments in the Buddhist year, grounding practice in the cycles of nature and memory.

Important Observances Include:

- New and full moon days – Uposatha (precept-renewal) ceremonies

- Vesak (Buddha’s Birthday) – Celebrated on the 8th day of the 4th lunar month

- Bodhidharma Day – Honoring the founder of Chan in China

- Rains Retreat (Vassa / Ango) – A three-month intensive practice period held during summer

- Ancestor Memorials – Honoring monastic ancestors, teachers, and patriarchs

- Ullambana Festival – Rituals for relieving the suffering of hungry ghosts and deceased relatives

During Ango (literally, “peaceful dwelling”), monks and nuns devote themselves to deeper practice. This includes daily meditation, extended silence, and the closing shuso hossenshiki—a public Dharma encounter where a senior practitioner demonstrates their understanding before the community.

Monastic life in the Chan tradition is not cloistered retreat, but cultivated simplicity.

Its structure does not confine, but supports. In robes, in silence, in dawn bells and evening chants, the Dharma is lived—not as philosophy, but as rhythm. In the space between footsteps, or in the stillness between breaths, the Way is already here.

Meditation Manuals, Zuochan Yi, and the Emergence of Koans

Despite its identification with seated meditation (zuochan), the early Chan school produced relatively few explicit instructions on the method or posture of meditation.

In the eighth century, during the time of the East Mountain tradition—under Patriarchs Daoxin (580–651) and Hongren (601–674)—we find several texts that offer guidance in concentration, contemplation, and visualization. Yet these texts do not quite form meditation manuals in the formal sense. Rather, they reflect the living oral tradition of monastic instruction, emphasizing personal awakening over systematic technique.

For several centuries thereafter, Chan literature largely avoided direct discussions of meditation methods.

Through the later Tang, Five Dynasties, and early Song, Chan was more concerned with lineage, encounter dialogue, and the transmission of mind than with written technique. The rhetoric of spontaneity, immediacy, and “no-method” meditation discouraged the formal documentation of practice.

It was not until the Song dynasty—confronted by the resurgence of Neo-Confucian scholarship and a broader literate public—that Chan began to articulate its internal practices in textual form.

The spread of printing, the growing role of lay practitioners, and the need to preserve tradition against intellectual critique gave rise to a new phase in Chan literary history.

Chan now looked back to its own classical era and began systematizing and recording the teachings of its patriarchs. Among the first to do so was Changlu Zongze, a monk of the early twelfth century and compiler of the Chanyuan Qinggui. It was Zongze who authored one of the earliest and most influential Chan meditation texts: the Zuochan Yi (Principles of Seated Meditation).

The Zuochan Yi of Changlu Zongze

In the Zuochan Yi, Zongze provides a clear and concise guide to seated meditation, drawing on a lineage of earlier Chinese sources.

He warns practitioners of the “doings of Mara” (mo shi)—mental distortions and delusions that may arise during advanced stages of meditation—and advises the reader to consult foundational texts for further clarification. These include the Surangama Sutra, Tiantai’s Xiao Zhiguan (Short Treatise on Concentration and Insight), and the Xiuzheng Yi by Huayan-Chan master Zongmi (780–841).

Each of these texts played a role in shaping Chinese contemplative practice:

- The Surangama Sutra, popular in the Song period, outlines fifty demonic mental states that may arise in meditation, offering detailed psychological warnings.

- The Xiao Zhiguan by Zhiyi (538–597), founder of the Tiantai school, was the first widely accessible primer on seated meditation in China. It offered concrete, progressive instructions on posture, breath regulation, and mental clarity.

- The Xiuzheng Yi of Zongmi integrates Tiantai and Huayan perspectives within a Chan framework, presenting a comprehensive vision of the contemplative path, grounded in the Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment.

The Zuochan Yi distilled these teachings into a simple, direct form accessible to monastics and educated laypeople alike.

It described in practical terms how to sit, how to align the body and breath, how to settle the mind, and how to face arising thoughts without clinging. Zongze’s approach was not only instructional, but also protective—seeking to prevent common errors and encourage stable, embodied awakening.

Through the Zuochan Yi, Chan meditation was reintroduced not as a mystical ideal, but as a reproducible and integrated practice.

It became possible to teach meditation in public without betraying the lineage of mind-to-mind transmission. Chan could now articulate its path in language while pointing beyond it.

The Rise of Koan Practice

Parallel to the formalization of zuochan instruction was the emergence of the koan (gong’an) tradition.

Koans had long existed as stories, dialogues, or cryptic utterances remembered from encounters between Chan masters and disciples. In the Song period, however, they became systematic tools for training—especially in the Linji lineage, where they were used to awaken insight and test realization.

The use of koans—seemingly nonsensical questions, paradoxes, or single-word challenges—was designed to exhaust the conceptual mind.

Koans such as “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” or “What was your original face before your parents were born?” are not puzzles to be solved, but invitations to let go of thought altogether. In the Rinzai tradition, each stage of a monk’s training was often marked by the resolution of a koan, with direct interaction between teacher and student forming the heart of the process.

In this way, Chan evolved into a tradition of two complementary disciplines:

- Seated meditation (zuochan), emphasizing silence, posture, and awareness

- Koan introspection, emphasizing spontaneity, tension, and insight through direct challenge

Both methods reflected the same essence: the transformation of the mind through direct experience.

Whether through stillness or confrontation, Chan asked practitioners to encounter their own nature face-to-face—beyond text, beyond thought.

The Transmission of Chan to Korea, Vietnam, and Japan

By the late Tang and early Song dynasties, Chan Buddhism had become one of the most vibrant and widely practiced forms of Buddhism in East Asia.

Its simplicity, its rejection of excessive scholasticism, and its emphasis on direct realization resonated across cultural borders. From the mountains and temples of China, Chan teachings spread into Korea, Vietnam, and Japan, giving rise to enduring local forms—Seon, Thiền, and Zen.

Korea: Seon Buddhism and the Nine Mountain Schools

Chan entered Korea in the late 8th century, where it came to be known as Seon (선).

One of the earliest transmitters was the Korean monk Pomnang, said to have studied with the Chinese master Daoxin. More systematic transmission began in the 9th century, when monks like Doui and Moui returned from China with direct Chan training. They established what would later be called the Nine Mountain Schools—regional Seon lineages modeled on Chinese Chan institutions.

Among these schools, the Gaji San school, founded by Beomnang, and the Sumi San school, founded by Daegak Guksa, became especially influential.

Korean Seon initially mirrored the Chinese emphasis on lineage and meditation but gradually integrated with Korea’s broader Buddhist scholastic traditions. By the 12th century, Seon had become the dominant form of Korean monastic Buddhism, culminating in the formation of the unified Jogye Order in the modern era.

Korean Seon preserved the spirit of both sudden awakening and gradual cultivation, a dual approach later formalized by Jinul (1158–1210). Jinul’s synthesis became the philosophical foundation of Korean Seon practice, deeply influencing both monks and lay practitioners to this day.

Vietnam: Thiền and the Trúc Lâm Tradition

In Vietnam, Chan arrived as Thiền (禪) through both direct Chinese transmission and interaction with Indian and local Southeast Asian Buddhist currents.

By the 10th century, Thiền had established itself through figures like Vinitaruci, an Indian monk who trained in China before transmitting the practice to Vietnam. Subsequent generations of Vietnamese monks developed distinct Thiền lineages, often connected to Chinese schools like Caodong and Linji.

One of the most important developments in Vietnamese Zen came with Trần Nhân Tông (1258–1308), a former king who renounced the throne to become a monk.

He founded the Trúc Lâm school—a uniquely Vietnamese Thiền movement that emphasized moral conduct, lay-monastic harmony, and national identity. The Trúc Lâm tradition flourished in harmony with Confucian and Daoist influences, rooting Zen deeply in Vietnamese cultural soil.