The Lankavatara Sutra, Bodhidharma’s Outline of Practice, and Sengcan’s Trust in Mind

Introduction: The Awakened Echo

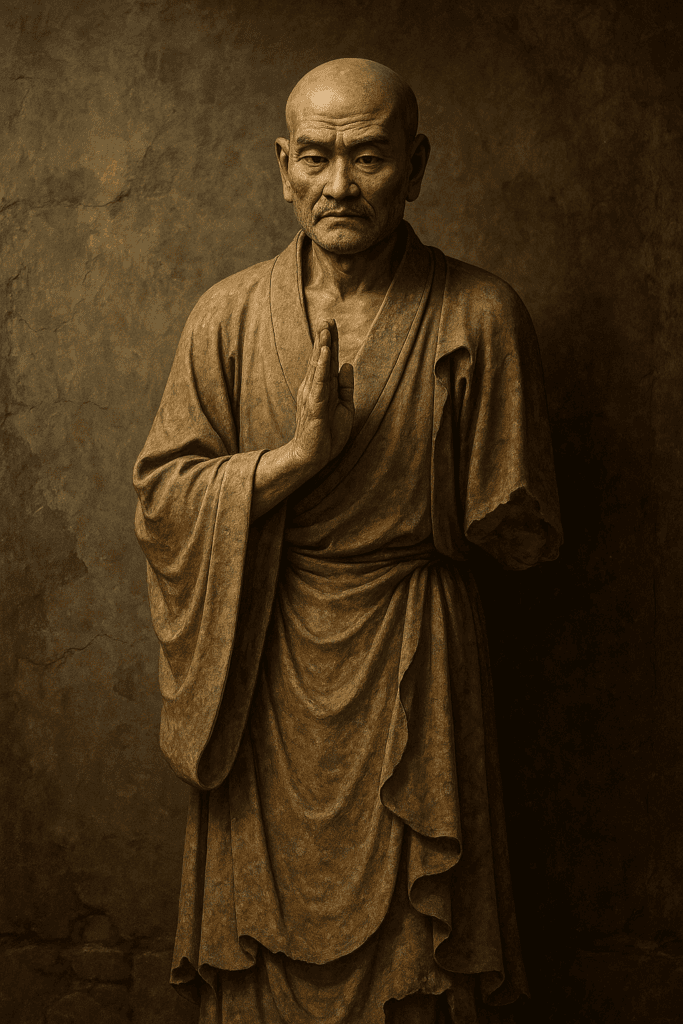

Across the shifting veils of time, a solitary figure moves in silence: Bodhidharma, Da-Mo, the red-bearded monk from the West. Neither scripture nor temple could contain him; neither kingdom nor fame could distract him. His journey eastward across the mountains of China was more than a pilgrimage — it was the transmission of a flame. A flame that would one day ignite the school of Chan.

Before Zen took root in the rocky gardens of Kyoto, before ink and brush traced its lessons into parchment and air, there were words — few and severe — that pointed beyond themselves. The Lankavatara Sutra, whispered between the lines of emptiness and mind. The Outline of Practice, a spare map for walking the path of detachment and compassion. Trust in Mind, a chant beyond opposites, where sorrow and joy are extinguished in the silent heart of reality.

These early texts are not sacred in the conventional sense. They are thresholds. They are the battered keys left behind by those who crossed over into the vast, formless shore of enlightenment.

In the sections that follow, we will walk alongside the spirit of Bodhidharma, tracing the birth of Chan Buddhism through its founding scriptures — texts that do not offer consolation, but instead demand the ultimate wager: the annihilation of illusion, and the flowering of a mind set free.

Listen carefully: through these words, a silence beckons.

Introduction: The Arrival of the Dharma in China

Long before the ink dried on the sacred scrolls of Chan, the great wheel of Buddhism had already begun its slow, deliberate turn into the heart of China. The teachings of the Buddha, born beneath the ancient trees of India, first reached Chinese soil during the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), carried by the hands and hearts of monks who journeyed along the Silk Road and across the southern seas.

These early transmissions, at first sparse and fragmentary, were soon nourished by the dedicated efforts of translators such as An Shigao, a Parthian monk working in the imperial capital of Luoyang in the second century, and Lokakṣema, who rendered profound Mahayana texts into the Chinese tongue. Over the centuries, more scholars and monastics would follow — Dharmarakṣa, Kumārajīva, Paramārtha — each carrying with them the shimmering, many-faceted jewel of the Dharma.

In their wake, entire traditions unfolded. The Yogacara, or “Consciousness-Only” school, found fertile ground through the work of Bodhiruci, Ratnamati, and the great pilgrim-translator Xuanzang, who returned from India with a trove of scriptures and luminous insight into Buddhist philosophy.

During the Tang dynasty, Chinese Esoteric Buddhism took root under the guidance of Subhakarasimha, Vajrabodhi, and Amoghavajra, weaving mantra, ritual, and vision into the imperial courts and great temples alike.

As dynasties rose and fell, Buddhism became woven into the very fabric of Chinese civilization, influencing art, literature, philosophy, and governance. In the Song dynasty, Chan Buddhism — terse, immediate, and unbound by words — ascended to prominence. It was then that the Five Houses of Chan arose, and the cryptic verses of the Blue Cliff Record and The Gateless Gate began to circulate among monks and seekers.

But before this flourishing, before even the first Chan monasteries were built among the misty hills, there was a seed planted by a solitary figure — a stranger from the West whose arrival would change the course of Chinese Buddhism forever.

In the sections that follow, we will meet this mysterious founder, Bodhidharma, and explore the founding scriptures — the Lankavatara Sutra, the Outline of Practice, and Trust in Mind — through which the Chan spirit first found its voice.

Bodhidharma: The Founder of Chan

As the Dharma made its slow, powerful descent into the fertile soil of China, it was inevitable that new forms would blossom — forms uniquely shaped by Chinese culture, philosophy, and spirit. But one figure stands at the gate of this transformation: Bodhidharma, known in Chinese as Da-Mo, the First Ancestor of the Chan school.

Scholars generally place Bodhidharma’s arrival in China around the late fifth or early sixth century, a time when China was divided among competing dynasties and Buddhist thought was rapidly evolving. His life, shrouded in layers of history and legend, marks the beginning of the Chan tradition — a lineage that would later rise to its literary and spiritual zenith during the Tang dynasty, China’s golden age.

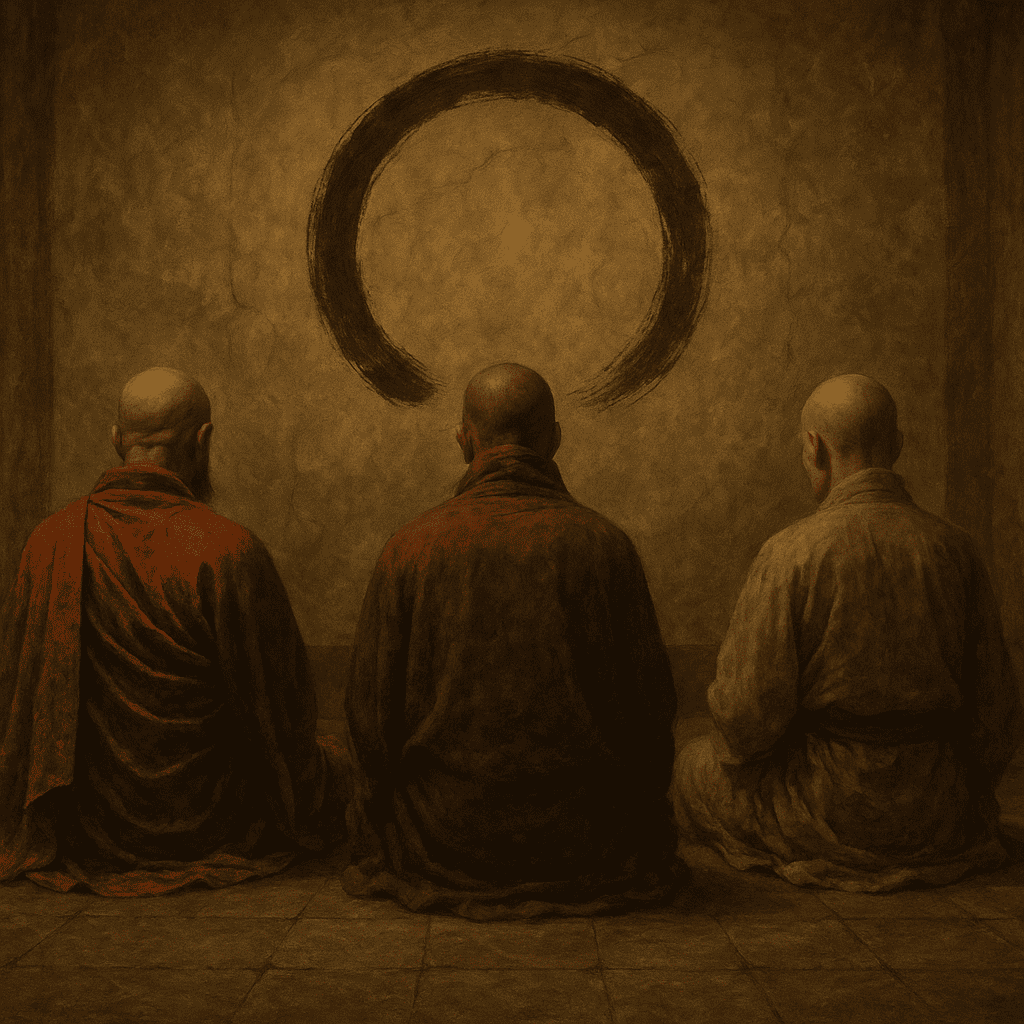

Chan Buddhism traces its essential teaching back to Gautama Buddha himself. In the silent Flower Sermon, the Buddha simply held up a white blossom; only his disciple Mahākāśyapa understood, responding with a faint smile. In that wordless moment, the “mind-seal” — the transmission of enlightenment beyond scriptures and speech — was passed down. Chan is the school that preserves this silent, direct transmission.

The Indian lineage of awakened Ancestors eventually reached Bodhidharma, the twenty-eighth in the line from Shakyamuni Buddha. Though traditionally referred to as a “Patriarch,” some modern scholars note that several early Ancestors may have been women, including Bodhidharma’s own teacher, Prajñātārā. “Ancestor,” then, is perhaps the more fitting title for these luminous figures.

Bodhidharma’s story is built from several early sources: the Record of the Buddhist Monasteries of Luoyang by Yáng Xuànzhī (547 CE), the preface to the Long Scroll of the Treatise on the Two Entrances and Four Practices attributed to Bodhidharma, and the Further Biographies of Eminent Monks by Daoxin in the seventh century. Together, they weave a portrait of a figure both historical and mythic.

According to tradition, Bodhidharma was born in southern India — some say a Tamil Brahmin prince who forsook his royal birthright for the path of awakening. Later Japanese legends even claim Persian origins for him. Chinese lore calls him the “Blue-eyed Barbarian,” a striking image of foreignness and fierce determination.

Bodhidharma’s crossing into China, during the chaotic period between the Northern and Southern Dynasties, is said to have been as uncompromising as his teachings. He taught that enlightenment could not be found in words or rituals, but only through the direct experience of the mind’s true nature — a radical message that would seed the unique Chinese form of Buddhism we call Chan (禪, from the Sanskrit dhyāna, meaning meditation).

When Chan later reached Japan in the thirteenth century, it would become known by its Japanese name: Zen.

Legend credits Bodhidharma not only with founding Chan, but also with revolutionizing monastic life in China. He is said to have taught the monks of Shaolin Temple methods of physical training — the foundation of Shaolin kungfu — and to have introduced the drinking of tea as a stimulant to aid monks during long, silent meditations. It is said his eyes never closed, wide and unblinking in ceaseless vigil.

Ultimately, Bodhidharma’s life in China came to a mysterious end. After naming his successor, he is said to have been poisoned — a fittingly enigmatic exit for a master who refused the comforts of worldly recognition.

In the next sections, we will explore the scriptures and teachings associated with Bodhidharma: the Lankavatara Sutra, the Outline of Practice, and Trust in Mind. These are the early seeds of the Chan tradition — fierce, clear, and devastatingly direct — planted by a figure whose silent gaze still echoes across the centuries.

The Shaolin Monastery and Da-Mo’s Legacy

Long before the silent footsteps of Bodhidharma echoed in its halls, the Shaolin Monastery already stood at the foot of Mount Shaoshi, one of the sacred peaks of the Songshan mountain range.

Founded in 495 CE in Henan Province, the temple was originally established around the Indian monk Buddhabhadra — known to the Chinese as Batuo — and his two martial disciples, Huiguang and Sengchou. Chinese martial traditions, both hard and soft, had already flourished for centuries, yet Shaolin would become something different: a crucible where Buddhist discipline and martial strength were fused into a single, enduring way of life.

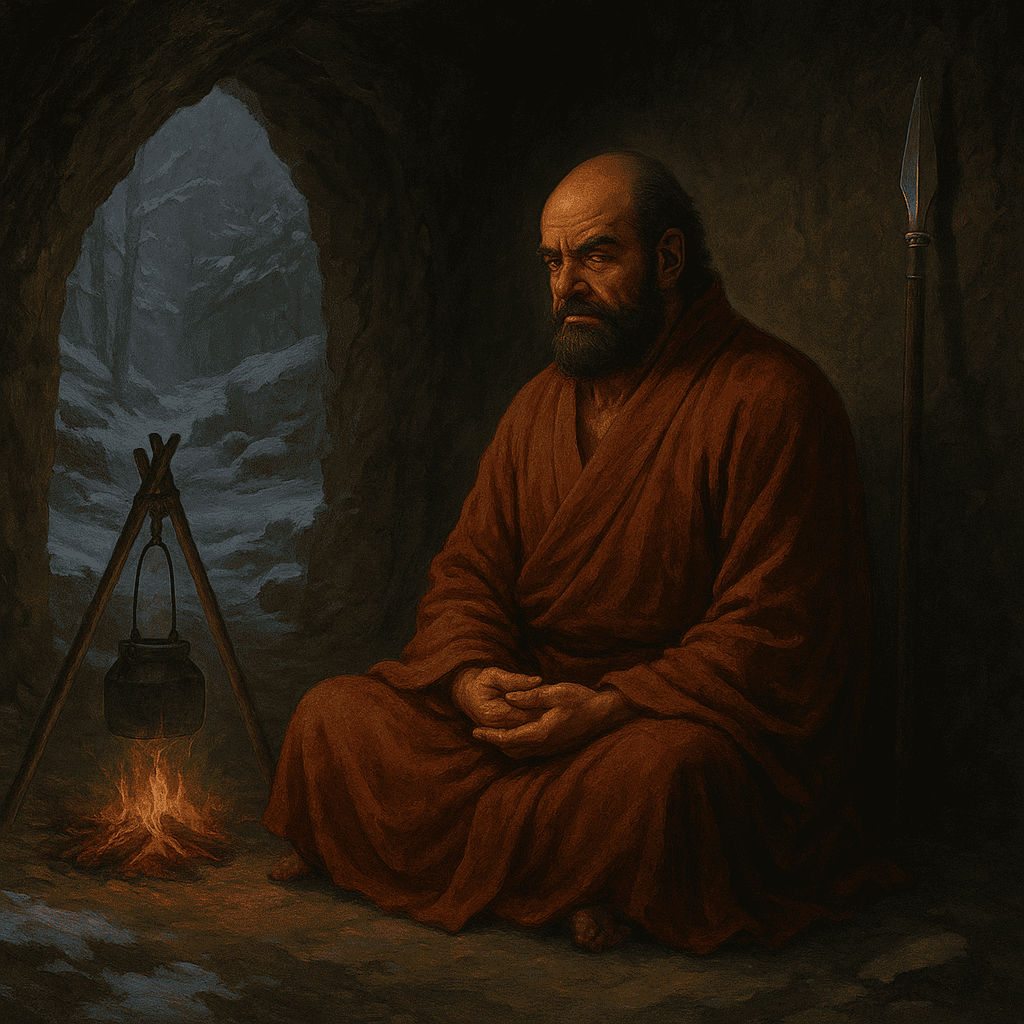

Shortly after its founding, Bodhidharma — Da-Mo — arrived at Shaolin. According to legend, he found no interest among the monks in his radical teachings of direct realization. Rather than seek followers, he withdrew to a mountain cave behind the monastery, where he faced the wall and meditated in silent, unwavering concentration for nine long years. This method became known as bìguān (壁觀) — “wall-gazing” — a practice of deep contemplation and the quieting (anxin, 安心) of the restless mind.

The story of Bodhidharma’s vigil became even more dramatic with the arrival of Shen Guang, a fierce and proud monk whose initial arrogance was worn away by years of devotion. To prove his determination, Shen Guang is said to have stood vigil over Bodhidharma during a heavy snowstorm, eventually cutting off his own left arm in a desperate plea to be accepted as a disciple. Moved by this sacrifice, Bodhidharma accepted him and gave him a new name: Dazu Huike.

Thus, the transmission continued. Dazu Huike succeeded Da-Mo as abbot of Shaolin and became the Second Ancestor of Chan Buddhism. To this day, Shaolin monks bow with only the right hand raised in prayer, in remembrance of Huike’s severed arm and unshakable resolve.

Following the teaching of his master, Huike preached that the Buddha-nature is already present within each being. Awakening is not won through endless rituals, scripture recitations, or moral good deeds, but through direct, intuitive realization — sudden enlightenment born from profound meditation.

Early Chan sources such as Tanlin and Daoxin describe Bodhidharma’s approach as rooted in both bìguān (wall-gazing meditation) and the study of the Lankavatara Sutra, a text which teaches that reality transcends words and concepts. True insight cannot be attained through language or logic; it must be realized inwardly, in a place beyond the reach of ordinary thought.

In this way, Bodhidharma’s influence at Shaolin was not limited to martial arts — though Shaolin wushu would later become legendary. His greater gift was the planting of a seed: the fierce, unyielding spirit of Chan, which taught that enlightenment is not a distant goal, but the silent truth already alive within each and every being.

The Shaolin Monastery and the Seed of Chan

Long before the silent footsteps of Bodhidharma touched its stone floors, the Shaolin Monastery already stood at the foot of Mount Shaoshi, one of the sacred peaks of the Songshan mountain range. Founded in 495 CE in Henan Province, the temple grew around the Indian monk Buddhabhadra — known in China as Batuo — and his martial disciples, Huiguang and Sengchou.

Ancient Chinese traditions of wrestling and martial technique were already known, but Shaolin would become something different: a furnace where inner cultivation and outward strength were fused into a singular spiritual path.

It was into this world that Bodhidharma — Da-Mo — arrived around 527 CE. His teachings were like cold iron against the skin: severe, uncompromising, direct. Rebuffed by the monks of Shaolin, Bodhidharma turned not to persuasion, but to silence.

He climbed behind the temple into the mountains, found a cave, and sat facing the sheer wall of stone. There he remained for nine years, in unbroken meditation, practicing bìguān — “wall-gazing” — a discipline of absolute stillness, where the mind’s restless waters are stilled into a mirror.

Winter fell hard upon the mountains. In the biting wind and snow, a fierce monk named Shen Guang, burning with pride and desperation, stood vigil outside Bodhidharma’s cave. For days he pleaded, but received only silence. At last, in an act of terrifying devotion, he drew his sword and severed his own left arm, offering it as proof of his sincerity. In the crimson snow, Bodhidharma turned — and thus the Dharma was transmitted.

Bodhidharma accepted him as a disciple, giving him a new name: Dazu Huike. With this new life, Huike was entrusted with the robe, the bowl, and a scroll of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra — the sacred text that Bodhidharma prized above all others, a scripture teaching that true reality is beyond all words and that enlightenment must be realized inwardly, not through ceremony, commentary, or deeds.

Dazu Huike became the Second Ancestor of Chan Buddhism, and the first Chinese-born bearer of the mind-seal transmission. In remembrance of his sacrifice, Shaolin monks bow to this day with only the right hand in prayer.

Huike, like the martial monks Huiguang and Sengchou, was skilled in both meditation and combat, embodying the union of inner and outer mastery. His practice of bìguān emphasized the sudden recognition of Buddha-nature, teaching that enlightenment was not distant, but immediate — as close as one’s own breath, if only the mind would become still enough to perceive it.

Following the paths of their masters, Bodhidharma and Huike lived not as lords of temples, but as wandering ascetics, sowing seeds of awakening across a restless land.

Among Huike’s disciples was Jianzhi Sengcan, who would become the Third Ancestor of Chan. To him was given a new name — Sengcan, “Gem Monk” — and a charge to carry the Dharma forward. Sengcan would later be associated with the Xinxin Ming (“Trust in Mind”), the first written testament of Chan, singing the truth that when the mind is undivided, reality reveals itself in full.

Dayi Daoxin, the Fourth Ancestor, awakened under Sengcan’s guidance and was bid to spread the Dharma northward. Daoxin established the first organized Chan monastic community, weaving together meditation practice with daily life, giving form to what had once been only wandering spirit.

From these early generations, the silent river of Chan grew deeper. Later compilations, like Jìngjué’s Record of the Masters and Disciples of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, would preserve fragments of these ancient teachings, including the Treatise on the Two Entrances and Four Practices, traditionally attributed to Bodhidharma himself. In it, the core doctrines of non-duality, emptiness, and inherent Buddha-nature were set forth — brief, sharp, and luminous like the light flashing from a sword’s edge.

Chan was born not from temples or kings, but from silence, sacrifice, and a flame that no winter could extinguish. Its true temples were caves, mountains, and the marrow of human bones. Its true scripture was not ink and parchment, but the living realization that enlightenment is not found elsewhere — it must be seized in this very breath, this very moment.

Bodhidharma’s Guide: The Lankavatara Sutra

The Lankavatara Sutra stands as the first guiding text of the emerging Chan school, a scripture wrapped in mystery and depth, handed down by Bodhidharma to his disciple, Dazu Huike, the Second Ancestor of Chan. According to the account of Dayi Daoxin (580–651), Bodhidharma gave Huike not only the robe and bowl of transmission, but also the Lankavatara Sutra as the primary scripture of his teaching. In these earliest days, Chan was often called the “Lankavatara school,” reflecting its reliance on this enigmatic text.

The Lankavatara Sutra — the “Scripture of Entering into Lanka” — was composed in classical Sanskrit during the mid-fourth century CE. Although scholarship generally points to Indian origins, some have suggested that the sutra, or parts of it, may have been shaped or even compiled by Chinese monastics. In any case, it first surfaces historically in China, where it found a powerful and lasting home.

Two Central Indian monks were responsible for the sutra’s first Chinese translations. The first, Dharmakshema, journeyed by land but was later assassinated; his translation disappeared after two centuries. The second, Guṇabhadra, arrived by sea and found imperial support under the Liu Song Dynasty. In 443 CE, Guṇabhadra completed his translation at the Chihuan Monastery in Tanyang. It was this version of the Lankavatara Sutra that Bodhidharma carried, studied, and transmitted in the Luoyang area during the sixth century.

“Lanka” — the sacred island — evokes the ancient memory of Sri Lanka, where Buddhist tradition holds that the Buddha himself visited three times. Sri Lanka would become the birthplace of the Pali Canon during the Fourth Buddhist Council in 29 BCE, preserving the Theravada tradition.

Yet the Lankavatara Sutra does not emerge from Theravada, but from the Yogacara stream of Mahayana Buddhism — the Great Vehicle. This Mahayana vision carries teachings of compassion, the six transcendent practices (paramitas), the profound Bodhisattva path, and the radical doctrine of the emptiness of all dharmas, or phenomena.

In its method, the Lankavatara echoes the “Ten Stages” doctrine of the great Avatamsaka Sutra — the Flower Garland Scripture — a monumental text composed between the first century BCE and the fourth century CE. Through its intricate visions, the Avatamsaka teaches the gradual unfolding of the Bodhisattva, stage by stage, into ultimate enlightenment.

The Lankavatara Sutra sharpens this vision with the precision of Yogacara philosophy. It speaks of the eight forms of consciousness, including the subtle ālaya-vijñāna — the “storehouse consciousness” — the unseen ground where karmic seeds are stored. It teaches of the tathāgata-garbha, the hidden “womb of Buddhas,” the latent, luminous nature present in all beings.

Above all, the Lankavatara insists: what we perceive as life and world are nothing but projections of the mind. Samsara and nirvana, birth and death, self and other — all are mirages born from ignorance. True reality, a boundless Oneness, cannot be grasped by thought or word; it must be entered directly through profound meditation.

The path it lays out is steep: ten stages of meditative absorption (samadhi), culminating in the transcendence even of samadhi itself. Beyond thought, beyond striving, there arises a serene joy — the illumination of nirvana — the extinguishing of duality, the awakening into what is beyond measure.

The sutra thus proclaims the Middle Way: neither eternalism nor nihilism, neither clinging to existence nor fleeing into annihilation. In this silent, measureless realm beyond concepts, the true nature of all things is revealed — vast, eternal, and utterly free.

It is no wonder, then, that the Chan lineage, which traces its awakening back to the wordless transmission between Shakyamuni Buddha and Mahākāśyapa — a flower held aloft, a silent smile — found its first true scripture in the Lankavatara Sutra. Here was a teaching that mirrored their deepest insight: that ultimate truth lies beyond words, beyond rites, beyond even the mind that seeks it.

The seed that Bodhidharma planted at Shaolin would, through this living transmission of silence, grow into the great flowering of Chan.

✦ The Lankavatara Sutra at a Glance ✦

- Origins: Composed in classical Sanskrit (4th century CE); transmitted to China by Dharmakshema and Guṇabhadra.

- Key Philosophies:

▸ Yogacara (“Mind-Only”): Reality arises from consciousness alone.

▸ Tathāgata-garbha: All beings contain the latent seed of Buddhahood.

▸ Eight Consciousnesses: Including the subtle storehouse consciousness (ālaya-vijñāna). - Path to Awakening:

▸ Ten stages of samadhi (meditative absorption).

▸ Final transcendence beyond samadhi into luminous, nondual realization. - Central Teachings:

▸ Life is an illusion created by the mind.

▸ True reality is wordless, formless, beyond dualities.

▸ The Middle Way beyond eternalism and nihilism.

▸ Enlightenment through direct insight, not through scripture or ritual. - Legacy:

▸ The sutra deeply shaped early Chan (Zen) Buddhism.

▸ Bodhidharma gave it to his disciple Huike as the heart of the Chan transmission.

Bodhidharma’s Outline of Practice

Among the few works attributed to Bodhidharma, the Outline of Practice shines with a terse, uncompromising clarity. Though scholars often view most texts connected to Bodhidharma as pseudonymous, this short tract has long been cherished within the Chan tradition as a distillation of his fierce and direct approach to the Path.

In the Outline of Practice, Bodhidharma reflects on how one enters the Way — the Dao — through two gates: by reason and by practice. “Reason” refers to a deep intuitive grasp of the truth, often approached through meditation or through the Daoist ideal of wuwei (無為) — “non-doing,” a surrender into the natural flow of existence. “Practice” entails deliberate effort, a patient shaping of character and conduct to harmonize with the Dharma.

Bodhidharma identifies four essential practices for those who would walk the Path:

- Endure

Suffering Injustice Patiently (Enduring Suffering): Facing hardship and insult without anger or resentment, understanding suffering as the inevitable working out of past karma. - Adapt

Detached Adaptation to the World (Accepting Conditions): Moving through life without clinging to pleasure or recoiling from pain, adapting fluidly to changing circumstances. - Detach

Cessation of Seeking (Seeking Nothing): Cultivating non-attachment, ending the restless search for external satisfactions, and embracing the empty heart of freedom. - Be Good

Practicing the Dharma (Aligning with the Way): Living virtuously with compassion, generosity, and ethical conduct, embodying the spirit of the Buddha’s teachings.

Though tradition ascribes other sermons to Bodhidharma — the Bloodstream Sermon, Wake-up Sermon, and Breakthrough Sermon — it is likely these were composed by later disciples seeking to extend his fierce simplicity into new forms.

Later centuries would weave additional legends around Bodhidharma, linking him to the origins of Chinese martial arts. Two famous manuals, the Yi Jin Jing (Muscle and Tendon Changing Classic) and the Xi Sui Jing (Marrow and Brain Washing Classic), were traditionally attributed to him. However, these works were most likely composed much later, between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, and reflect Daoist Qigong practices more than early Chan teachings.

The Yi Jin Jing, for instance, appears to have been written in 1624 by a Daoist priest named Zining. This text, a manual of daoyin — Daoist life-energy cultivation and body-strengthening exercises — claimed discovery at Shaolin Temple long after Bodhidharma’s time. It was not until the nineteenth century, as shown in the research of Japanese martial arts scholar Ryuchi Matsuda, that Bodhidharma became widely associated with the origins of martial arts at Shaolin.

By the twentieth century, popular imagination had crowned Bodhidharma as the progenitor of Shaolin boxing (quan) and, by extension, of all Chinese martial arts (gongfu). Yet what Bodhidharma truly bequeathed to Shaolin — and to the world — was not a system of physical defense, but an indestructible spirit: a spirit of silent endurance, unwavering insight, and the fierce patience of the seeker who, having ceased seeking, finds everything.

Just as Shaolin monks refined their bodies through gongfu, so too did the early Chan ancestors refine their minds through the practices outlined by Bodhidharma: silent acceptance, effortless adaptability, non-attachment, and compassionate action — the true martial arts of the spirit.

✦ The Outline of Practice at a Glance ✦

- Entry into the Path:

▸ By Reason (meditation and non-doing / wuwei)

▸ By Practice (deliberate cultivation) - The Four Essential Practices:

▸ Suffering Injustice Patiently: Enduring hardship without anger, understanding karmic causality.

▸ Detached Adaptation to the World: Moving fluidly through changing conditions without attachment.

▸ Cessation of Seeking: Letting go of desires and resting in emptiness.

▸ Practicing the Dharma: Living virtuously through compassion, generosity, and ethical action. - Legacy:

▸ Core guide for Chan practitioners seeking direct realization beyond ritual or scripture.

▸ Embodies the spirit of silent, patient, unwavering practice that defined early Chan.

Sengcan’s Trust in Mind

Among the earliest and most enduring echoes of the Chan spirit is a poem of radiant clarity: the Xinxin Ming (信心銘), often translated as Trust in Mind. Attributed to Sengcan (496–606), the Third Ancestor of Chan Buddhism, this short work stands as the first written declaration of the Chan school’s essential teaching — a teaching beyond scripture, beyond philosophy, beyond even the striving mind itself.

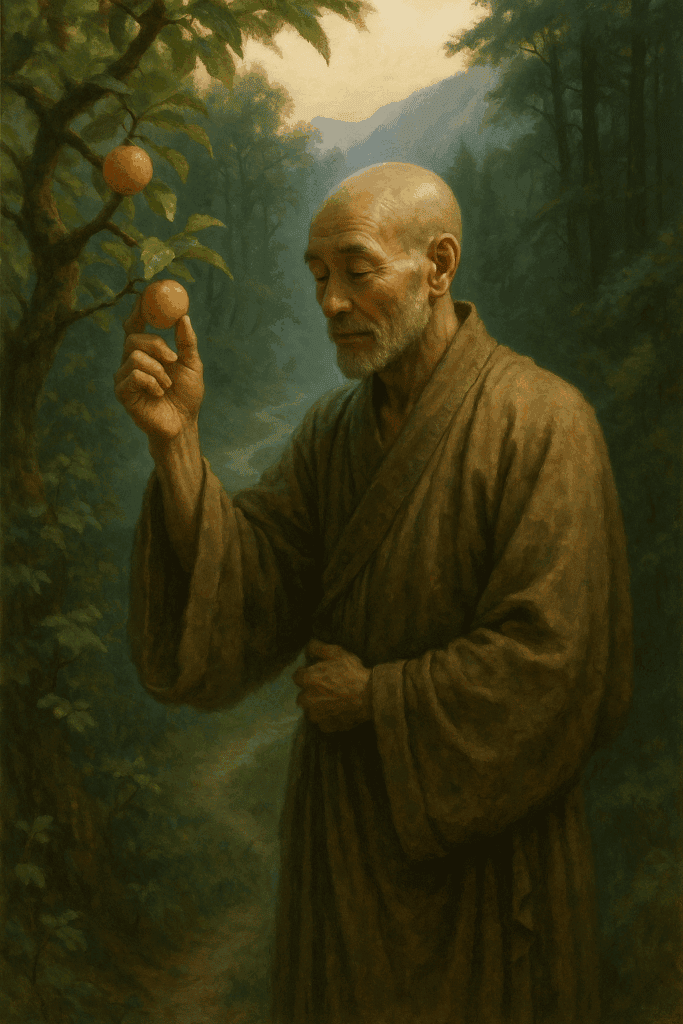

Sengcan lived as a wandering ascetic, following the transmission from Bodhidharma to Huike with silent fidelity. His life, like his poem, is veiled in mystery, but the Trust in Mind shines through the mists of history with timeless simplicity.

The Xinxin Ming offers one of the earliest descriptions of Chan meditation. It sings of a path where all opposites dissolve — where joy and sorrow, gain and loss, sacred and profane, are seen as illusions arising from the mind’s restless division. True understanding, Sengcan teaches, is not found through effort or analysis, but through a profound trust: a return to the undivided, original nature of mind.

The key themes of the Trust in Mind include:

- Non-Duality: Enlightenment comes when one no longer clings to distinctions between self and other, good and evil, right and wrong. To set up even the slightest opposition is to fall away from the natural truth.

- Effortless Practice: True practice is not the anxious striving to attain, but the serene release of striving itself. Trust arises when the mind no longer grasps at success or fears failure.

- Unity of Mind: When mind ceases to judge, compare, or discriminate, it returns to its original stillness — vast, boundless, and free.

- The Middle Way: Following the Buddha’s path beyond extremes of affirmation and negation, being and non-being.

A few famous lines capture the spirit of the Xinxin Ming:

“The Great Way is not difficult,

for those who have no preferences.

When love and hate are both absent,

everything becomes clear and undisguised.”

In this early scripture of Chan, Sengcan points not to a doctrine but to an experience: a trust so deep that the mind rests naturally in the Way, just as a river flows effortlessly to the sea.

Trust in Mind would quietly become one of the foundational texts of Chan and later Zen Buddhism, embodying the spirit of a tradition that teaches not through words, but through the life beyond words — a direct, unshakable trust in the luminous, empty heart of mind itself.

✦ Trust in Mind at a Glance ✦

- Author:

▸ Sengcan (496–606), Third Ancestor of Chan. - Essence of the Teaching:

▸ Enlightenment arises from trusting the undivided nature of mind. - Key Themes:

▸ Non-Duality: All opposites dissolve when seen with true understanding.

▸ Effortless Practice: Awakening comes by letting go of striving and resistance.

▸ Unity of Mind: True clarity appears when judgment and comparison cease.

▸ Middle Way: Liberation beyond affirmation and negation, being and non-being. - Famous Lines:

▸ “The Great Way is not difficult, for those who have no preferences.” - Legacy:

▸ First written declaration of Chan Buddhism’s essential approach to meditation and enlightenment.

▸ Continues to influence both Chan and Zen traditions as a core articulation of the direct path.

The Silent Transmission

The journey of early Chan — from the caves of Shaolin to the wandering ascetics of the mountains — can be heard through three voices, three teachings, each seamlessly joining the next like a single breath unfolding into the vast sky.

The Lankavatara Sutra offers the philosophical foundation: that reality is mind-only, that words and forms are illusions, and that true liberation lies beyond all conceptual grasping. It calls the seeker inward, to the unborn, undying nature that no scripture can contain.

Bodhidharma’s Outline of Practice brings this vision into daily life. It teaches the way of direct cultivation: to endure hardship without resentment, to adapt without clinging, to cease restless seeking, and to practice virtue with an empty hand. It is the path of silent, steadfast walking through the fleeting world.

Sengcan’s Trust in Mind completes the circle, dissolving even the effort to attain. It whispers that the Great Way is not difficult — only abandon preferences, and the original stillness of mind will reveal itself. No striving, no achievement: only trust, and the Way appears, as natural as the return of light at dawn.

Taken together, these three teachings form a single, living instruction:

Realize that nothing is apart from mind; live without grasping; trust the mind as it is.

Thus the true teaching of Chan is not found in words or sutras. It is found in the breath you are taking now — silent, boundless, already complete.