Theravada, Mahayana, Chan and Zen

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Entering the Stream of Zen

- The Tripiṭaka and Early Buddhist Texts

- Vinaya: The Monastic Discipline

- Suttas: Sermons of the Buddha

- Abhidharma: Psychology and Insight

- The Chinese, Korean, and Japanese Canons

- Transmission and Translation of the Canon

- Taishō Tripiṭaka

- Early Buddhist Canons and Variants

- Mahayana Foundations and Philosophy

- Birth of the Mahayana

- Prajñāpāramitā and the Bodhisattva Ideal

- Madhyamaka and Yogācāra School

- Chan Buddhist Literature in China

- Early Texts and Lineage Records

- Laṅkāvatāra and Trust in Mind

- Early Chan Masters and Monastic Codes

- Japanese Zen Literature

- Rinzai Zen: Koans and Direct Transmission

- Sōtō Zen: Dōgen and the Shōbōgenzō

- Zen Poets: Ikkyū and Ryōkan

- Modern Transmission and Global Zen

- Meiji Reformers and Modern Commentators

- The Western Lineage: Deshimaru, Suzuki, Katagiri

- Lineage and Living Tradition

- Conclusion: Walking the Path with Words and Silence

Introduction: Entering the Stream of Zen

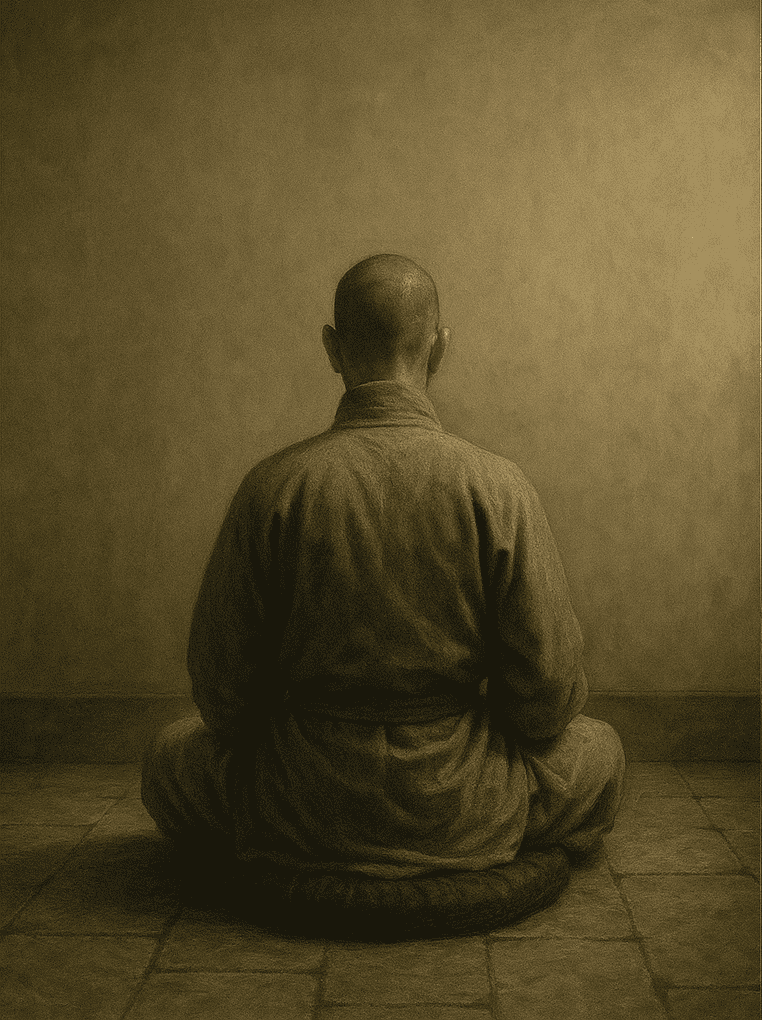

There is a stream that has flowed for over two thousand years—fed by mountain rains of India, winding through the forests of China, the islands of Japan, and into the great oceans of the modern world. This is the stream of Zen Buddhism, and its path is marked not only by silence, stillness, and meditation, but also by words—strange, luminous words, often poetic, sometimes fierce, always alive.

This book is a companion for the journey. It does not offer a single doctrine or formula. Rather, it opens the gates to the essential writings that have shaped Zen thought and practice from the Buddha’s first teachings under the Bodhi tree to the handwritten poems of hermits and monks, and onward to the Dharma halls and urban temples of today.

To read Zen literature is to sit beside the masters—to overhear their laughter, their long silences, their sudden shouts. These texts are not meant to be admired from a distance; they are meant to be lived with, argued with, puzzled over, and finally, dissolved into. As the great teacher Dōgen said, “To study the Way is to study the self. To study the self is to forget the self.”

In these pages, we will follow the unfolding of Zen from its Indian and Chinese foundations to its flowering in Japan and its transmission to the West. Along the way, we will meet sages and rebels, poets and reformers, all part of a lineage of living fire.

This guide is written for the serious student, the curious beginner, and the lifelong practitioner. It is for those who wish not merely to read about Zen, but to taste the marrow of its living teachings.

Let us enter together—not as tourists, but as travelers ready to wake up.

Fundamental Early Buddhist Texts

The Tipiṭaka

The Buddhist scriptures are contained within the Tipiṭaka (Pāli; Sanskrit: Tripiṭaka), meaning “Three Baskets,” compiled between roughly the sixth and first centuries BCE. The first complete Buddhist canon was the Pāli Canon of Theravāda Buddhism, finalized at the Fourth Buddhist Council in North India during the first century BCE.

The Mahāyāna Buddhist tradition, while expanding its scriptures beyond the early canon, also preserved the Tripiṭaka, first translating it from Sanskrit into Chinese and later adapting it into Korean, Japanese, Tibetan, and, eventually, English versions.

The Pāli Tipiṭaka is organized into three primary collections (piṭakas):

- Vinaya Piṭaka — the monastic code of discipline for monks and nuns (compiled circa sixth century BCE)

- Sutta Piṭaka (Sanskrit: Sutra Piṭaka) — the sermons and discourses of the Buddha (compiled circa fifth century BCE)

- Abhidhamma Piṭaka — philosophical and psychological analysis and interpretation of the Buddha’s teachings (compiled circa third century BCE)

Together, these three “baskets” form the foundation of Buddhist doctrine, practice, and philosophy across all major Buddhist traditions.

Vinaya: The Monastic Code

The Vinaya Piṭaka is the earliest of the three divisions of the Buddhist canon and was compiled soon after the death of Gautama Buddha. It remains the oldest surviving Buddhist textual collection, outlining the ethical framework and daily regulations for members of the monastic community (saṅgha).

The Theravāda Vinaya Piṭaka, known as the Book of Discipline, is divided into three main parts:

- Suttavibhaṅga — the detailed analysis of the rules for monks (bhikkhus) and nuns (bhikkhunis), explaining the origins and applications of each precept.

- Khandhaka — a compilation of procedures and protocols for monastic life, divided into two subsections:

- Mahāvagga — narrates key events in the Buddha’s ministry after his enlightenment, including the first sermons, the establishment of the early saṅgha, the first ordinations, and the authorization of monastic initiation ceremonies and vows.

- Cullavagga — details the development of further monastic regulations, disciplinary actions, and the formation of the community of ordained women (bhikkhunis).

- Mahāvagga — narrates key events in the Buddha’s ministry after his enlightenment, including the first sermons, the establishment of the early saṅgha, the first ordinations, and the authorization of monastic initiation ceremonies and vows.

- Parivāra — a later appendix of summaries, explanations, and catechisms designed to aid in the study and memorization of the Vinaya rules.

The Vinaya prescribes guidelines for virtuous behavior, daily conduct, dress, meals, lodging, ceremonial observances, dispute resolution, and the consequences for transgressions. It reflects both practical governance and an ideal of communal harmony based on mutual respect, compassion, and personal discipline.

Through centuries of transmission, the Vinaya has continued to serve as the ethical foundation for Buddhist monastic communities throughout Asia, ensuring that the life of a monk or nun is one of simplicity, mindfulness, and unwavering commitment to the path of liberation.

The Vinaya serves not only as a rulebook but as a guide to harmonious communal life and spiritual practice.

Key Functions of the Vinaya

| Function | Description |

| Ethical Guidance | Establishes a moral code promoting non-harming, honesty, mindfulness, and compassion. |

| Community Harmony | Provides rules for resolving disputes, maintaining unity, and fostering mutual respect. |

| Monastic Training | Structures the daily life, duties, and rituals of monks and nuns to support spiritual cultivation. |

| Discipline and Accountability | Outlines consequences for breaking precepts, encouraging personal responsibility and integrity. |

| Preservation of the Saṅgha | Maintains the purity and credibility of the Buddhist monastic community across generations. |

Suttas (Sutras): The Sermons of the Buddha

The Sutta Piṭaka forms the second division of the Tipiṭaka (Pāli Canon), the scripture of Theravāda Buddhism, composed and organized after the First Buddhist Council around the fifth century BCE. It contains the discourses (suttas) attributed to the historical Buddha and his close disciples. The Sutta Piṭaka is traditionally divided into five major collections (nikāyas):

- Dīgha Nikāya — The Long Discourses of the Buddha

- Majjhima Nikāya — The Middle-Length Discourses

- Saṃyutta Nikāya — The Connected Discourses

- Aṅguttara Nikāya — The Numerical Discourses

- Khuddaka Nikāya — The Collection of Short Texts

Among the oldest materials within the Sutta Piṭaka is the Sutta Nipāta (“Suttas Falling Down”), found within the Khuddaka Nikāya. Scholars regard it as one of the earliest layers of Buddhist literature, possibly composed during the Buddha’s own lifetime.

Following the Sutta Nipāta, texts such as the Itivuttaka (“This Was Said by the Blessed One”) and Udāna (“Inspired Utterances”) likely emerged shortly after the Buddha’s death, while the other four major nikāyas were organized by the time of the First Buddhist Council, around 400 BCE.

The Jātaka Tales, also preserved within the Khuddaka Nikāya, are a vast collection of folk stories and poems recounting Gautama Buddha’s previous lives as animals, humans, spirits, and gods. Comprising 547 poems, they were initially composed around the fourth century BCE and expanded through the fourth century CE.

These stories illustrate the long spiritual journey over countless lifetimes required to achieve Buddhahood. The Nidānakathā, a 2nd–3rd century CE introduction to the Jātaka commentary, provides a biographical narrative of the Buddha’s life.

Several critical doctrinal suttas are preserved in the Sutta Piṭaka:

- The Ānanda Sutta (in the Saṃyutta Nikāya) emphasizes the doctrine of anattā (non-self), a core Buddhist teaching intricately linked with dependent origination, impermanence, and non-clinging.

- The Ariyapariyesanā Sutta (The Noble Search) from the Majjhima Nikāya recounts Gautama Buddha’s spiritual journey, including his encounters with his two meditation teachers, Āḷāra Kālāma and Uddaka Rāmaputta.

Among the most important meditation instructions recorded are:

- Ānāpānasati Sutta (Mindfulness of Breathing Discourse), detailing the method of mindfulness of breathing (ānāpānasati) as a foundational meditation practice.

- Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta (The Discourse on the Establishing of Mindfulness) and Mahāsatipaṭṭhāna Sutta (The Great Discourse on the Establishing of Mindfulness), which set forth the systematic practice of mindfulness (sati), becoming the textual cornerstone for the Theravāda Vipassanā (insight) meditation tradition.

Finally, central to the Khuddaka Nikāya is the Dhammapada, a third-century BCE anthology of the Buddha’s pithy sayings on ethics, wisdom, and liberation. The Dhammapada remains one of the most beloved and widely quoted works of Buddhist literature worldwide.

Overview of the Five Nikāyas

| Nikāya | Translation | Content Focus | Notable Texts |

| Dīgha Nikāya | Long Discourses | 34 lengthy suttas covering profound doctrinal topics, cosmology, ethics, and meditation practices. | Mahāparinibbāna Sutta (Buddha’s Final Teachings) |

| Majjhima Nikāya | Middle-Length Discourses | 152 suttas of moderate length dealing with meditation, wisdom, and detailed instructions for practice. | Ariyapariyesanā Sutta (The Noble Search); Ānāpānasati Sutta (Mindfulness of Breathing) |

| Saṃyutta Nikāya | Connected Discourses | Thematically grouped suttas exploring key concepts like non-self, causality, and mindfulness. | Ānanda Sutta (Teaching on Non-Self) |

| Aṅguttara Nikāya | Numerical Discourses | Suttas organized by numerical categories, summarizing progressive aspects of the path. | Various gradational teachings (e.g., Five Precepts) |

| Khuddaka Nikāya | Collection of Short Texts | A diverse anthology including poems, stories, verses, and early canonical texts. | Sutta Nipāta, Dhammapada, Jātaka Tales, Udāna |

Abhidharma: Commentary and Buddhist Psychology

The Abhidhamma Piṭaka (Pāli) or Abhidharma (Sanskrit), meaning “Higher Teaching” or “Basket of Higher Knowledge,” forms the third and final division of the early Buddhist canon. It comprises a detailed scholastic analysis of the Buddha’s teachings (the suttas/sutras) and is often described as the earliest form of Buddhist psychology and philosophy of mind.

Whereas the suttas primarily focus on practical teachings and ethical training, the Abhidharma systematizes those teachings into a comprehensive theoretical framework. Known as Buddhism’s “map of the mind,” it categorizes all elements of existence (dharmas) and provides intricate models for understanding consciousness, mental states, causality, and perception.

In Tibet and East Asian Mahāyāna traditions, the principal Abhidharma text was traditionally The Compendium of Higher Teaching (Abhidharmasamuccaya), composed by Asaṅga, an Indian Brahmin-born monk who lived in the Gandhāra region (modern-day Kashmir) during the fourth to fifth centuries CE. Asaṅga’s Mahāyāna Abhidharma advanced an ontology of 100 types of phenomena (dharmas), classifying existence into:

- 28 physical phenomena

- 52 mental factors

- 24 types of causal relations

- 17 kinds of mental processes

- 89 types of consciousness

Asaṅga’s half-brother, Vasubandhu, initially a scholar of the Śrāvakayāna tradition, outlined a slightly different model. He proposed 75 fundamental dharmas and 51 mental factors. Vasubandhu famously distilled the Abhidharma literature of his time into concise four-line verses (kārikā) and expanded upon them in his major work, The Treasury of Higher Dharma (Abhidharmakośa), which remains a foundational text for both Theravāda and Mahāyāna Buddhist study.

Asaṅga and Vasubandhu are revered not only as masters of Abhidharma analysis but also as the founders of the Yogācāra (“Practice of Yoga”) school of Mahāyāna Buddhist philosophy.

Today, especially within Theravāda and Tibetan Buddhist traditions, the study of Abhidharma endures as a tool for analyzing and deconstructing the mind’s subjective experiences, aiming toward insight into the nature of reality. See The Buddhist Psychology of Awakening by Steven D. Goodman for an accessible introduction.

Importantly, as the Buddha emphasized skepticism, personal verification, and evidence-based inquiry, Buddhist psychology aligns closely with the spirit of modern scientific psychology. However, from the Buddhist perspective, while science is the best available method for understanding the objective, conventional world, it remains limited when it comes to grasping ultimate, non-conceptual reality.

Influence on Mahāyāna Philosophy

The Abhidharma laid the groundwork for the two principal schools of early Mahāyāna Buddhist philosophy:

- Madhyamaka (“Middle Way” school), founded by Nāgārjuna, which systematically analyzed existence and refuted all intrinsic, independent essence in phenomena, leading to the doctrine of śūnyatā (emptiness).

- Yogācāra (“Practice of Yoga” school), associated with Asaṅga and Vasubandhu, which explored consciousness, perception, and the subjective construction of reality.

Both schools, while differing in method, were profoundly influenced by the Prajñāpāramitā (“Perfection of Wisdom”) literature, which emphasized the emptiness and interdependence of all phenomena. According to Mahāyāna understanding, ultimate reality transcends conceptualization; no entity exists independently or permanently. Everything arises in dynamic relation to everything else.

Viewed together, Madhyamaka and Yogācāra offer complementary insights:

- Madhyamaka adopts an ontological approach, emphasizing the analysis of existence and non-existence.

- Yogācāra approaches through psychological analysis, examining how consciousness structures experience.

Ultimately, both schools guide practitioners toward the same realization: the nondual, interconnected nature of reality, and liberation from the illusions of separateness and permanence.

Early Buddhist Canons

As Buddhism spread and diversified across India and beyond, each early Buddhist school developed its own version of the Tripiṭaka (“Three Baskets”)—the standard division of Buddhist scriptures into Vinaya (monastic rules), Sutta/Sutra (sermons), and Abhidhamma/Abhidharma (philosophical analysis). However, in practice, the canons of these schools often varied considerably in content, structure, and even language.

Some schools expanded their canons beyond the basic three baskets. These additional collections included:

- Vidyādhāra Piṭaka (“Basket of Knowledge Bearers”) — collections of incantations and magical spells (dhāraṇī).

- Mantra Piṭaka and Dhāraṇī Piṭaka — compilations of protective chants and esoteric formulas.

- Bodhisattva Piṭaka — scriptures focused on the teachings and practices of the Bodhisattva path, later associated with the emerging Mahāyāna movement.

By the early centuries of the Common Era, several distinct early Buddhist canons had developed. The 8th-century Chinese pilgrim Yijing recorded that the non-Mahāyāna (Nikāya) Buddhist schools preserved different Tripiṭakas, each with both intentional and accidental variations. According to Yijing, four major canonical traditions were recognized:

- Mahāsāṃghika Tripiṭaka — maintained in a Prakrit or Hybrid Sanskrit language; said to comprise approximately 300,000 slokas (verse lines).

- Sarvāstivāda Tripiṭaka — preserved in Sanskrit, also comprising around 300,000 slokas.

- Sthavira Tripiṭaka — likewise consisting of 300,000 slokas; the Pāli Canon of Theravāda Buddhism is considered a southern branch version of this tradition.

- Saṃmitīya Tripiṭaka — a shorter collection of around 200,000 slokas, though none of the original texts in their original language have survived.

Although many sub-schools and sects branched off from these major traditions, Yijing observed that the sub-sects generally retained the Tripiṭaka of their “mother tradition,” maintaining a “continuous arya tradition” even while developing distinct practices and interpretations.

The famed 7th-century pilgrim Xuanzang reported that he brought back to China the Tripiṭakas of at least seven different Buddhist schools, including the Mahāsāṃghika, Sarvāstivāda, Sthavira, Dharmaguptaka, Kāśyapīya, and Mahīśāsaka.

According to Buddhist historian A. K. Warder, citing the Tibetan historian Bu-ston, by the first century CE there were already eighteen schools of Buddhism, each maintaining its own version of the Tripiṭaka, many of which had by then been committed to written form. However, except for the Pāli Canon—preserved in full—and fragmentary remains of other collections, most of these early scriptures have been lost or remain undiscovered.

Thus, the early Buddhist canons reflect not only a vibrant and diverse literary activity but also the rich doctrinal evolution that shaped Buddhist thought across centuries and cultures.

Buddhist Canons Across East Asia

Buddhist scriptures have been preserved and transmitted through several great canons across Asia, each reflecting the spiritual, philosophical, and historical development of the Dharma in different cultures.

The Chinese Buddhist Canon, the Korean Tripiṭaka Koreana, and the Japanese Taishō Tripiṭaka represent monumental efforts to collect and organize Buddhist teachings from India, Central Asia, China, Korea, and Japan. Meanwhile, the Tibetan Canon offers a distinct and comprehensive record of Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna traditions. Together, these canons form the backbone of Buddhist literature, study, and practice across East Asia and beyond.

The Chinese, Korean, and Japanese Canons

The Chinese Buddhist Canon is a vast collection of scriptures that encompasses translations of the Pāli Canon as well as a large body of Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna texts, originally composed in India, China, Central Asia, and Japan. Over the first 1,500 years following the historical Buddha’s life, Buddhist scholars and monks compiled approximately 1,662 sutras into this canon.

The collection includes a wide range of teachings across various movements and philosophical schools, such as the Prajñāpāramitā Sutras (Perfection of Wisdom texts), Pure Land (Amitābha) Buddhism, Yogācāra (Consciousness-Only) philosophy, Tiantai/Tendai traditions, Shingon (Esoteric Buddhism), Nichiren teachings, Nāgārjuna’s Madhyamaka (Middle Way) philosophy, and large compendia such as the Mahāratnakūṭa Sutra—a collection of forty-nine major Mahāyāna sutras.

The Tripiṭaka Koreana

The Tripiṭaka Koreana (팔만 대장경, 八萬大藏經) is one of the most remarkable achievements in Buddhist textual history. Carved onto 81,258 wooden printing blocks during the 13th century in Korea, it preserves a near-perfect edition of the Chinese Buddhist Canon. It was created under the Goryeo dynasty both as a devotional act and as an effort to invoke protection from Mongol invasions.

Remarkably, the woodblocks survived multiple wars and disasters and are today housed at Haeinsa Temple. The Tripiṭaka Koreana remains one of the most complete and accurate extant versions of the Chinese Buddhist texts.

The Taishō Tripiṭaka

Building upon the foundation of the Tripiṭaka Koreana, the Taishō Tripiṭaka (Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō, 大正新脩大藏經) was compiled in Japan in the early 20th century. Initiated by Takakusu Junjirō and Watanabe Kaigyoku in 1924, the first edition was completed by 1962 in Tokyo.

While many texts were based on the Tripiṭaka Koreana, the Taishō editors reordered the material according to historical development and textual genre, rather than following the traditional Chinese and Korean system that placed Mahāyāna sutras first.

The Taishō Tripiṭaka distinguishes itself by including:

- A broader range of Esoteric Buddhist texts, sourced from Japanese temple manuscripts.

- Manuscripts recovered from the Dunhuang caves in China, representing early and unique Buddhist materials.

- Japanese Buddhist writings, particularly from the Kamakura and later periods, although still composed in Classical Chinese.

The structure of the Taishō is as follows:

- Volumes 1–55: Core Buddhist scriptures, including Agamas (early discourses), Mahāyāna sutras, and Vinaya (monastic discipline texts).

- Volumes 56–84: Japanese Buddhist literature (primarily in Classical Chinese).

- Volumes 85–97: Buddhist art drawings, including detailed depictions of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and mandalas.

- Volumes 98–100: Comprehensive indexes and bibliographies.

In total, the Taishō Tripiṭaka consists of 100 volumes, comprising 5,320 individual texts organized into 11,970 fascicles.

Today, the Taishō Tripiṭaka is the most widely used edition of the Buddhist Canon among Chinese, Korean, and Japanese traditions. Since 1982, under the leadership of Yehan Numata, the Buddhist organization Bukkyō Dendō Kyōkai (Society for the Promotion of Buddhism) has been undertaking the English translation of the Taishō Canon. Learn more about the Translation Project here.

The Tibetan Canon

A third major Buddhist canon is the Tibetan Canon, which was compiled primarily between the 8th and 14th centuries CE. It consists of two main parts:

- The Kangyur (“Translated Words”): Texts attributed directly to the historical Buddha, including sutras and vinaya.

- The Tengyur (“Translated Treatises”): Commentarial works by Indian and Tibetan scholars on the sutras, abhidharma (philosophical texts), tantra (esoteric works), and medical and scientific treatises.

The Tibetan Canon reflects both the Indian Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna traditions, and contains a significant number of esoteric tantric texts not preserved in Chinese or Pāli collections. Due to its comprehensive preservation of both sutra and tantra, the Tibetan Canon remains vital for the study of late Indian Buddhism.

The Mongolian Buddhist Canon

The Mongolian Buddhist Canon is a classical body of translations central to the Buddhist tradition of Mongolia. Modeled largely on the Tibetan Buddhist canon, it consists of two main divisions: the Kanjur (translations of the Buddha’s words) and the Tenjur (commentaries and treatises by Indian and Tibetan masters).

Translation efforts began as early as the Yuan dynasty (13th–14th centuries) and were completed in the 17th century under the patronage of Ligdan Khan and the Gelug school, led by the religious leader Zanabazar. The final, full edition was printed under the supervision of the Qing dynasty’s Qianlong Emperor in the 18th century, utilizing elaborate woodblock printing technology.

The Mongolian canon contains not only Tibetan texts but also unique works not found in the standard Tibetan collections, reflecting Mongolia’s distinct contributions to the Buddhist literary tradition.

The Nepalese Sanskrit Buddhist Canon

The Nepalese Buddhist textual tradition, centered in the Kathmandu Valley, is a unique corpus that preserves Sanskrit originals of many Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna scriptures otherwise lost in India. Maintained primarily by the Newar Buddhist community, this tradition continued to copy and transmit Sanskrit manuscripts well into the modern period.

Following the destruction of India’s great Buddhist monasteries in the 12th century, Nepal became a vital center for Buddhist scholarship, attracting Tibetan monks who sought authentic texts. Newar Buddhist clergy, including the śākyabhikṣus and vajrācāryas, maintained high proficiency in Sanskrit, making Nepal an enduring bridge between classical Indian Buddhism and Tibetan and modern Buddhist studies.

In the 19th century, scholars like Brian H. Hodgson facilitated the transfer of many Nepalese manuscripts to academic institutions in India and Europe, greatly influencing contemporary Buddhist scholarship. Today, Newar Buddhist literature continues in a blend of Sanskrit and Newari, reflecting a living tradition with deep historical roots.

Here’s a brief account of the Digital Sanskrit Buddhist Canon (DSBC) in the same polished style as your other sections:

The Digital Sanskrit Buddhist Canon

The Digital Sanskrit Buddhist Canon (DSBC) is a major digital humanities project dedicated to preserving and disseminating the surviving corpus of Sanskrit Buddhist literature. Initiated by the University of the West in partnership with the Nagarjuna Institute in Kathmandu, Nepal, the DSBC project seeks to create an accessible online archive of Sanskrit Buddhist texts, many of which had been scattered, endangered, or difficult to access.

The project’s scope is vast: it aims to digitize at least 600 Mahāyāna Buddhist sūtras and treatises preserved in Sanskrit. As of the latest updates, the DSBC has successfully digitized over 604 texts—equivalent to roughly 50,000 pages—with more than 369 scriptures made publicly available through its official website. The collection continues to expand as more manuscripts are transcribed, edited, and shared, providing an invaluable resource for scholars, practitioners, and students worldwide.

The DSBC represents a major effort to safeguard and revitalize the Sanskrit Buddhist heritage, bridging ancient tradition with modern technology.

Early Essential Texts

Several early Buddhist texts outside the Tipiṭaka became foundational to the development of Buddhist narrative, philosophy, and historical tradition. These works offer insight into both early Buddhist thought and the later emergence of Mahāyāna perspectives.

Mahāvastu (“Great Story” or “Great Event”)

The Mahāvastu is a compendium of Jātaka (stories of the Buddha’s previous lives) and Avadāna (narrative tales), along with accounts of the life of Śākyamuni Gautama and some of his key disciples. Compiled between the 2nd century BCE and the 4th century CE, the Mahāvastu belongs to the Lokottaravāda branch of the Mahāsāṃghika school. It is a key text for understanding early Buddhist hagiography.

(See: A Summary of the Mahāvastu by Bimala Churn Law.)

Avataṃsaka Sūtra (“Flower Garland Sutra” or “Flower Adornment Scripture”)

Composed and compiled between the 1st century BCE and the 4th century CE, the Mahāvaipulya Buddhāvataṃsaka Sūtra (commonly known as the Avataṃsaka Sūtra) is one of the most influential Mahāyāna scriptures. It portrays the cosmos as a vast, interdependent network of luminous realms, emphasizing the infinite manifestations of the Buddha’s wisdom.

Important sections include:

- Daśabhūmika Sūtra (“Ten Stages Sutra,” Chapter 26) — describing the ten stages of the bodhisattva’s spiritual development.

- Gaṇḍavyūha Sūtra (“Flower Array Sutra,” Chapter 39) — a detailed pilgrimage narrative culminating in the realization of enlightenment. Early partial translations appeared in Chinese as early as the 2nd century CE; the first complete Chinese version was translated by Buddhabhadra around 420 CE.

Vimalakīrti Nirdeśa Sūtra (“The Teaching of Vimalakīrti”)

Likely composed around 100 CE, this Mahāyāna sutra presents the layman Vimalakīrti as a master of nonduality and śūnyatā (emptiness). It challenges rigid distinctions between lay and monastic practitioners and emphasizes the wordless realization of ultimate truth. Vimalakīrti’s famous teaching of silence, in response to a question about the nature of reality, became emblematic of Mahāyāna thought.

The sutra was translated into Chinese by Kumārajīva in 406 CE.

Buddhacarita (“Acts of the Buddha”)

Two early biographies of Gautama Buddha bear the title Buddhacarita. The first was authored by Sangharakṣa, and the second, more famous version, was composed by the poet-monk Aśvaghoṣa (c. 80–150 CE). Aśvaghoṣa’s Buddhacarita is a sophisticated Sanskrit epic that narrates the Buddha’s life up to his awakening, blending devotion with literary artistry.

Lalitavistara Sūtra (“The Play in Full”)

Compiled around the 3rd century CE from multiple sources, the Lalitavistara is a semi-mythological biography recounting the Buddha’s life up to his first sermon. Richly symbolic, it portrays the Buddha’s existence as a divine “play” to liberate beings from suffering. Scenes from this sutra are famously depicted in the stone reliefs of Borobudur Temple in Java, Indonesia.

Dīpavaṃsa (“Chronicle of the Island”)

The Dīpavaṃsa is the earliest historical record of Sri Lanka and one of the first narrative histories in Buddhist literature. Likely compiled between the 3rd and 4th centuries CE from earlier Theravāda commentaries (Atthakathā) and other sources, it intertwines ancient Indian and Sri Lankan history, recounts the legend of the Buddha’s three visits to Sri Lanka, and documents the spread of Buddhism on the island. The Dīpavaṃsa was the first Buddhist chronicle translated into English and was later expanded upon by the more famous Mahāvaṃsa (“Great Chronicle”).

Vasubandhu’s Abhidharmakośa and Yogācāra Treatises

Vasubandhu (c. 400–480 CE) stands as one of the most influential philosophers in the history of Indian Buddhism. Originally trained in the Sarvāstivāda and Sautrāntika schools, he later converted to Mahāyāna Buddhism alongside his half-brother Asaṅga and became a major figure in the foundation of the Yogācāra (“Consciousness Only”) school.

His Abhidharmakośa-kārikā (“Verses on the Treasury of Abhidharma”) is a seminal work, composed in the 4th–5th centuries CE. It summarizes Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma thought in approximately 600 Sanskrit verses, with an auto-commentary (Abhidharmakośa-bhāsya) that critically examines and refines these doctrines through debate, logical argument, and scriptural exegesis.

Later, Vasubandhu composed key Mahāyāna treatises such as the Viṃśatikā (“Twenty Verses”) and Triṃśikā (“Thirty Verses”), presenting the clearest and most succinct articulations of Yogācāra’s “Consciousness Only” philosophy. His works continue to shape Buddhist philosophy in both East Asian and Tibetan traditions.

Buddhaghosa’s Visuddhimagga (“Path of Purification”)

The Visuddhimagga (“Path of Purification”), composed by Buddhaghosa in the 5th century CE, is considered the most important work of Theravāda Buddhism after the Tipiṭaka itself. Synthesizing centuries of commentary and oral tradition, it systematically outlines the entire Buddhist path of practice.

The text details forty meditation subjects and offers a comprehensive guide to samatha (calm meditation), vipassanā (insight meditation), and samādhi (meditative absorption). Buddhaghosa emphasizes that the ultimate aim of Buddhist meditation is samādhi—the unified, luminous mind that realizes full enlightenment (nibbāna). The Visuddhimagga serves as both a manual for meditation and a bridge between theoretical understanding and experiential realization.

Chinese Chan Literature

Birth of Mahāyāna and the Earliest Chinese Translations

Mahāyāna, meaning “Greater Vehicle” in Sanskrit, was so named in contrast to what Mahāyāna Buddhists termed Hīnayāna (“Lesser Vehicle”). The so-called Hīnayāna teachings — preserved in the early scriptures (Nikāya) — emphasized personal liberation (nirvāṇa) and are most fully represented today in the Theravāda tradition.

Between approximately 100 BCE and 100 CE, Buddhist monks began composing Mahāyāna sūtras. Several hundred such texts were produced, primarily in Sanskrit, emerging from India, Central Asia, and eventually East Asia.

Unlike the early Nikāya suttas, which purport to record the historical Buddha’s spoken teachings, Mahāyāna sūtras are often visionary compositions—poetic and expansive works attributed to revelations received during intense meditation or inspired dreams. While they claim a connection to the Buddha or exalted bodhisattvas, these claims, though historically unlikely, do not undermine the spiritual authenticity or transformative value of their teachings.

Māhāyāna sūtras are comparable not to the Vinaya (monastic rule) or early suttas as strict records, but rather to the Abhidharma tradition, in that they constitute later systematic expositions of the Buddhist path. However, Mahāyāna teachings offer a sharp critique of the Abhidharma’s realist assumptions, asserting instead the doctrine of emptiness (śūnyatā): the view that all phenomena (dharmas), like the self, are empty of inherent existence.

Mahāyāna philosophy evolved from the foundational teachings of the historical Buddha but for centuries existed within the broader monastic establishment as a dispersed literary and devotional movement, rather than as a separate sect. Only around the sixth century CE did Mahāyāna identity consolidate into distinct schools with their own monasteries, practices, and institutional forms.

Scholar Paul Williams notes that Mahāyāna likely arose among monks who withdrew from urban centers to live more ascetically in the wilderness, emulating Siddhārtha Buddha’s original renunciant life (Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations). From these solitary or forest-dwelling practitioners emerged a profound ideal: the way of the bodhisattva.

The Bodhisattva Ideal

Originally, the term bodhisattva (“awakening being”) referred to anyone earnestly seeking enlightenment. Over time, it came to denote specifically those who vow to postpone their own final liberation in order to lead all sentient beings out of suffering.

In Mahāyāna literature, a Bodhisattva (capitalized) often refers to exalted celestial figures—such as Mañjuśrī (embodying wisdom), Avalokiteśvara (embodying compassion; Kannon in Japan), and Maitreya (the future Buddha)—who serve as spiritual archetypes on altars, in chants, and in devotional art. These figures symbolize the fundamental aspects of buddhahood present in all beings.

The bodhisattva vows to forgo the limited goal of arhatship (individual nirvāṇa) in order to engage in the vast and compassionate project of universal liberation. He or she cultivates non-attachment not only to self but even to the concept of ultimate reality, practicing skillful means (upāya): the flexible adaptation of teachings to suit the needs and capacities of different beings. In the bodhisattva’s great compassion, even descending into hell realms to offer assistance is considered a virtuous act.

Following the traditional Jātaka tales, this is the very path that Śākyamuni Buddha himself is said to have undertaken across countless lifetimes.

For the bodhisattva, nirvāṇa is not a distant goal to be attained apart from the world, but a natural unfolding within saṃsāra (birth and death). Enlightenment is not separate from the illusory world; rather, it is found precisely through the deep realization of the world’s non-substantial, interconnected, and dynamic nature.

The essence of Perfect Wisdom (prajñāpāramitā)—as taught in early Mahāyāna sūtras—is the insight that all forms, perceptions, and distinctions are ultimately empty. Even enlightenment itself is seen as an empty construct: a necessary guide, but not absolute truth.

Thus, Mahāyāna meditation is not grasping at ideas but resting in the direct flow of pure awareness, free of conceptual elaboration. In truth, even this “state” cannot be adequately described, for all descriptions fall short of the boundless reality they aim to convey.

The Six Perfections

The bodhisattva embodies the awakened mind (bodhicitta) in action through the practice of the six pāramitās (“perfections”), first systematically listed in early Mahāyāna texts such as Nāgārjuna’s Letter to a Friend (1st–2nd century CE):

- Dāna — Generosity

- Śīla — Moral discipline

- Kṣānti — Patience

- Vīrya — Diligence

- Dhyāna — Meditation

- Prajñā — Wisdom

The vows of the bodhisattva, although in one sense impossible to fully accomplish within the limitations of ordinary existence, are not measured by literal completion. Rather, they express an infinite aspiration: a way of life rooted in compassion, insight, and boundless commitment to the awakening of all beings.

Mahāyāna Buddhism reshaped the Buddhist path into a universal, compassionate mission grounded in wisdom and nonattachment.

Key Features of Mahāyāna Thought

| Feature | Summary |

| Bodhisattva Ideal | A vow to seek enlightenment not for oneself alone, but to liberate all sentient beings. |

| Emptiness (Śūnyatā) | All phenomena (dharmas) are empty of inherent existence; reality is dynamic, relational, and nondual. |

| Skillful Means (Upāya) | Compassionate flexibility: teachings and methods are adapted to suit the needs of different beings. |

| Perfect Wisdom (Prajñāpāramitā) | Wisdom recognizes the emptiness of all concepts, including enlightenment itself. |

| Meditation as Nonattachment | Meditation rests not on clinging to ideas but on pure, concept-free awareness. |

| Six Perfections (Pāramitās) | Generosity, morality, patience, diligence, meditation, and wisdom guide the bodhisattva path. |

Mahāyāna Literature

The major literature of Mahāyāna Buddhism is vast and diverse, with certain key texts standing as pillars of its philosophical and devotional traditions. Foremost among them are the Prajñāpāramitā Sūtras, including the renowned Diamond Sūtra and Heart Sūtra. Other highly revered texts include the Lotus Sūtra, the Yogācāra Sūtras, the Vimalakīrtinirdeśa Sūtra, the Tathāgatagarbha Sūtras, and various esoteric (Tantric) scriptures. Collections of Samādhi Sūtras, Dhyāna Sūtras, bodhisattva-centered teachings, and other compilations also play central roles in the Mahāyāna tradition.

Mahāyāna Buddhism, initially a literary and philosophical movement, gradually became a major form of Buddhism, particularly with its rise in China and the subsequent spread across East Asia.

Early Mahāyāna Texts

One of the earliest known Mahāyāna scriptures is the Śālistamba Sūtra (“Sūtra of the Rice Stalk”), possibly composed as early as 200 BCE. Produced during a period when Mahāyāna coexisted alongside early Buddhist schools, it centers on the doctrine of dependent origination (pratītyasamutpāda), presenting it as the essence of the Dharma. The Śālistamba advances the view that conventional reality is an illusion (māyā), a theme that would come to define Mahāyāna philosophy.

The Sūtra of Forty-Two Chapters holds the distinction of being the first Buddhist text translated into Chinese. According to tradition, it was rendered into Chinese around 67 CE, although some scholars suggest it may have been compiled later. It consists of short aphoristic teachings attributed to the Buddha.

Legend recounts that in 64 CE, Emperor Ming of the Eastern Han Dynasty, inspired by dreams of a golden figure, dispatched two emissaries to India. They returned accompanied by two monks, Kāśyapa Mātaṅga and Dharmarakṣa, bearing Buddhist scriptures—including the Sūtra of Forty-Two Chapters—on white horses. In honor of their arrival, the emperor established the first Buddhist temple in China, the White Horse Temple (Báilǐsì), where the first Buddhist translations into Chinese were undertaken. Of the six original texts said to have been translated, only the Sūtra of Forty-Two Chapters remains extant today.

The Prajñāpāramitā Literature

Among the earliest and most foundational Mahāyāna texts are the Prajñāpāramitā Sūtras, dedicated to the exposition of transcendent wisdom (prajñāpāramitā). These works were largely shaped by the philosophical contributions of Nāgārjuna (c. 150–250 CE), the great Indian scholar and alchemist often regarded as the Fourteenth Ancestor in Chan tradition.

The Prajñāpāramitā corpus encompasses around forty sūtras composed between 100 BCE and 600 CE. These texts articulate the path of the bodhisattva through the practice of the six perfections (pāramitās) and stress the fundamental emptiness (śūnyatā) of all phenomena.

The earliest known text in this genre, the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra (“The Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand Lines”), dates to around 50 CE and is considered one of the earliest extant written Buddhist works. Over the following centuries, it was expanded into longer versions containing 10,000, 18,000, 25,000, and even 100,000 lines.

To make these teachings more accessible, shorter and more concentrated summaries were later composed—the most famous being the Heart Sūtra and the Diamond Sūtra. These concise sūtras distill the vast Prajñāpāramitā philosophy into highly condensed poetic expressions.

The first known Chinese translations of the Aṣṭasāhasrikā and other Mahāyāna texts were undertaken by Lokakṣema (c. 147–189 CE), who emphasized asceticism, meditation, and samādhi in his interpretations.

The Diamond Sūtra in Chinese Chan

In early Chinese Chan Buddhism, teachings were initially transmitted privately to a small number of students. However, by the time of Dàyì Dàoxīn (580–651), the Fourth Ancestor, Chan had expanded significantly, and Hóngrěn (601–674), the Fifth Ancestor, taught more than a thousand disciples.

Recognizing the need for a more accessible and powerful text for larger audiences, Hóngrěn emphasized the Diamond Sūtra (Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra), transmitting its teachings to his eminent disciple, Huìnéng (638–713), the Sixth Ancestor.

The Diamond Sūtra—subtitled “The Diamond That Cuts Through Illusions”—became a foundational scripture in the Chan tradition. A printed edition dated to 868 CE is the oldest known printed book in the world. Though traditional accounts attribute its authorship to the alchemist and philosopher Nāgārjuna, the true origins of the text remain anonymous, a fitting reflection of its teaching on the emptiness of all constructs.

The following key texts shaped the development of Mahāyāna philosophy and practice across Asia.

Key Mahāyāna Texts

| Sūtra | Focus | Approximate Date |

| Śālistamba Sūtra | Dependent origination and the illusory nature of reality | c. 200 BCE |

| Sūtra of Forty-Two Chapters | Early aphoristic teachings; first Chinese translation | c. 67 CE (traditional) |

| Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra | Early Prajñāpāramitā (“Perfection of Wisdom”) teachings | c. 50 CE |

| Heart Sūtra | Condensed summary of emptiness teachings | c. 200–400 CE |

| Diamond Sūtra | Teaching on the nonattachment to phenomena and wisdom beyond form | c. 300–500 CE (Chinese print: 868 CE) |

| Lotus Sūtra | Universality of Buddhahood and importance of faith and devotion | c. 1st–2nd century CE |

| Vimalakīrtinirdeśa Sūtra | Lay practitioner Vimalakīrti teaches nonduality and silence | c. 100 CE |

| Tathāgatagarbha Sūtras | Teachings on Buddha-nature within all beings | c. 2nd–4th century CE |

Early Mahāyāna Buddhist Philosophy and Key Texts

The two principal schools of early Mahāyāna Buddhist philosophy are Madhyamaka and Yogācāra. Both were deeply influenced by the Prajñāpāramitā (“Perfection of Wisdom”) literature, which teaches the emptiness (śūnyatā) of all phenomena (dharmas). These schools can be viewed as complementary approaches:

- Madhyamaka focuses on a systematic ontological analysis of reality.

- Yogācāra examines the structures of consciousness, perception, and cognition—effectively a Buddhist psychology.

Madhyamaka Philosophy

The Madhyamaka school, founded by the Indian philosopher and alchemist Nāgārjuna (c. 150–250 CE), develops the “Middle Way” between the extremes of existence and non-existence. Nāgārjuna’s seminal works, the Mūla-madhyamaka-kārikā (“Fundamental Verses on the Middle Way”) and the Vigrahavyāvartanī (“The Dispeller of Disputes”), set forth a radical critique of all conceptual elaboration, revealing that all views, including the view of emptiness itself, are ultimately empty.

Madhyamaka means “Middle Way,” emphasizing not only moral moderation but more profoundly a philosophical balance that avoids all extremes of affirming or denying existence.

One of the most concise expressions of Madhyamaka thought is found in the Heart Sūtra (Prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya), the best-known Mahāyāna scripture. Although brief, the Heart Sūtra encapsulates the profound teachings of emptiness and dependent origination. Traditionally attributed to Nāgārjuna’s lineage, the Heart Sūtra was composed between the 2nd and 4th centuries CE and later translated into standard Chinese by the great scholar-traveler Xuanzang (c. 602–664 CE) along with the complete Mahāprajñāpāramitā Sūtra.

Other Foundational Mahāyāna Texts

The Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra (“Great Nirvāṇa Sūtra”) was probably composed around the 2nd century CE. It survives today through Chinese translations by Faxian and Buddhabhadra (416–418 CE) and by Dharmakṣema (421–430 CE). This important Mahāyāna scripture teaches the doctrine of buddhadhātu (Buddha-nature), presenting enlightenment as the eternal “true self” underlying all beings.

The Indian monk and translator Kumārajīva (344–413 CE) played a crucial role in bringing Mahāyāna meditation texts to China. His first major translation, the Sūtra on the Concentration of Sitting Meditation, became the earliest Buddhist meditation manual available in Chinese.

Sengzhao (384–414 CE), one of Kumārajīva’s foremost disciples, further shaped Chinese Buddhist thought. In his Treatise of Sengzhao (Zhaolun), he elucidated Nāgārjuna’s philosophy of emptiness and the meaning of prajñāpāramitā (perfect wisdom), helping to ground Madhyamaka ideas in the Chinese intellectual tradition.

The Lotus Sūtra and the Chinese Schools

The Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtra (“The Lotus Sūtra”) was composed over approximately two centuries, between the 1st century BCE and the mid-2nd century CE. It became one of the most influential texts of Mahāyāna Buddhism, emphasizing the universality of Buddhahood and the compassionate activity of the Buddha across infinite worlds and ages.

The Lotus Sūtra was first translated into Chinese by Dharmarakṣa in 286 CE and again by Kumārajīva in 406 CE, the latter version becoming the most authoritative.

In China, the Lotus Sūtra became the central scripture of the Tiantai (Tientai) school—also known as the “Lotus School”—founded in the 6th century CE. It was the first distinctly Chinese Buddhist school and profoundly influenced East Asian Buddhism.

The Japanese Zen master Dōgen (1200–1253), founder of the Sōtō Zen tradition, esteemed the Lotus Sūtra as the supreme Buddhist scripture, writing in his Shōbōgenzō (“Treasury of the True Dharma Eye”) that it was the “great king and great master of all the various sutras that the Buddha Śākyamuni taught.”

The Lotus Sūtra teaches that the Buddha’s existence is eternal and manifests in countless forms to guide beings to enlightenment. It introduces the doctrine of expedient means (upāya): the idea that the Buddha’s teachings are skillfully adapted to the capacities of different beings, sometimes conveying provisional truths to lead them gradually toward ultimate realization.

Two of its most representative chapters are:

- Chapter 16: “The Lifespan of the Tathāgata” — revealing the Buddha’s timeless presence.

- Chapter 25: “The Universal Door of Avalokiteśvara Bodhisattva” (Guānyīn) — describing the compassionate responses of the Bodhisattva to all beings’ cries for help.

The following thinkers and texts shaped the foundations of Mahāyāna Buddhist philosophy and its transmission into China.

Key Early Mahāyāna Philosophers and Texts

| Figure or Text | Contribution | Approximate Date |

| Nāgārjuna | Founder of Madhyamaka school; emphasized emptiness (śūnyatā) | c. 150–250 CE |

| Mūla-madhyamaka-kārikā | Foundational treatise on the Middle Way and dependent origination | c. 2nd century CE |

| Vigrahavyāvartanī | Refutation of philosophical disputation | c. 2nd–3rd century CE |

| Heart Sūtra (Prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya) | Concise summary of the perfection of wisdom teachings | c. 2nd–4th century CE |

| Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra | Exposition of Buddha-nature (buddhadhātu) and eternal true self | c. 2nd century CE (Chinese translations 5th century) |

| Kumārajīva | Key translator of Mahāyāna texts into Chinese; introduced meditation manuals | 344–413 CE |

| Sūtra on the Concentration of Sitting Meditation | First Buddhist meditation manual available in Chinese | 4th–5th century CE |

| Sengzhao | Elucidated Nāgārjuna’s philosophy in China; author of Treatise of Sengzhao (Zhaolun) | 384–414 CE |

| Lotus Sūtra (Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtra) | Mahāyāna scripture on universal Buddhahood and expedient means | 1st century BCE–2nd century CE |

| Dharmarakṣa & Kumārajīva | Translated the Lotus Sūtra into Chinese | 3rd–5th century CE |

The First Ancestors of Chan

Bodhidharma, known in Chinese as Dámó, is recognized as the First Ancestor of Chan Buddhism. He is traditionally credited with authoring the short tract Outline of Practice, although most other works attributed to him are considered pseudonymous. The legendary Bodhidharma is remembered as the original founder of the Chan school—a tradition that, when transmitted to Japan in the thirteenth century, became known as Zen.

Dàoxìn (Dayi Daoxin, 580–651), the Fourth Ancestor of Chan, left a biographical account of Bodhidharma’s disciple Dàzǔ Huìkě (487–593), the Second Ancestor. According to Dàoxìn, Bodhidharma entrusted Huìkě with the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra as the central scripture for practice and realization. In its early days, Chan Buddhism was known as the “Laṅkāvatāra school” because of its reliance on this sūtra.

The Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra (“Scripture of the Descent into Laṅkā”), composed in Sanskrit around the mid-fourth century CE, was translated into Chinese soon after. As D. T. Suzuki notes in his Studies in the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, Laṅkā likely refers to an island in southern India—often identified with Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka)—though this is uncertain. The sutra presents a dialogue between the Buddha and the Bodhisattva Mahāmati, focusing on the direct realization of the mind’s ultimate nature.

Sēngcàn (496–606), the Third Ancestor of Chan, composed Trust in Mind (Xìnxīn Míng), one of the earliest poetic expositions of Chan meditation. It stands as the first written declaration of Chan Buddhism’s essential teaching: that true realization lies beyond dualistic thought.

Enlightened under Sēngcàn, Dàoxìn established himself as a key figure in the early Chan tradition. Ordained as a monk, he taught meditation at East Mountain Temple on Potou (“Broken Head”) Mountain—later known as Shuangfeng (“Twin Peaks”)—in Huangmei County, Hubei Province. Dàoxìn is credited with founding the first recognized Chan monastic community, where meditation became the central practice. His teachings, later compiled as The Five Gates of Dàoxìn, appeared some sixty years after his death.

Related Developments in Chinese Buddhism

Contemporaneous with these early Chan figures was Zhìyǐ (538–597), founder of the Tiantai tradition in China (known as Tendai in Japan). Tiantai was the first systematic and indigenous Chinese Buddhist school, synthesizing meditative and doctrinal practices. Dōgen, the Japanese founder of the Sōtō Zen school, later studied under the Tiantai tradition before forming his own path.

Zhìyǐ’s Lesser Treatise on Concentration and Insight (Xiao Zhiguan) became the first comprehensive Chinese Buddhist meditation manual, while his Great Treatise on Concentration and Insight (Mohe Zhiguan) formed the central scripture of the Tiantai school. In his Rules in Ten Clauses (Lizhi fa shitiao), Zhìyǐ instructed monks to dedicate four periods of each day to meditation.

Monastic Discipline and Histories

The Brahmā’s Net Sūtra, translated into Chinese in the sixth century, laid out the Ten Major Precepts and Forty-Eight Minor Precepts later embraced by Chan Buddhism. This influential text also introduced the figure of Vairocana Buddha, the Primordial Buddha embodying the Dharma itself.

Meanwhile, Huìjiāo (497–554) compiled the Biographies of Eminent Monks (Gāosēng Zhuàn), cataloging 257 biographies of notable Buddhist monastics, offering a glimpse into the lives and practices of early Chinese Buddhism.

Later, Dàoxuān (596–667) became the most prominent figure of the Lü tradition (Vinaya school) in China. His Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks (Xù Gāosēng Zhuàn), containing 485 biographies, profoundly influenced the rules and ethos of emerging Chan monastic communities.

The early Chan Ancestors laid the foundation for a uniquely Chinese expression of meditative Buddhism.

The First Five Ancestors of Chan Buddhism

| Ancestor | Dates | Key Contribution |

| Bodhidharma (Dámó) | fl. 5th–6th c. CE | Founded the Chan tradition; emphasized meditation and the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra. |

| Dàzǔ Huìkě (Huike) | 487–593 | Received transmission from Bodhidharma; upheld the focus on mind-to-mind teaching. |

| Sēngcàn (Sengcan) | 496–606 | Authored Trust in Mind (Xìnxīn Míng); taught nondual meditation. |

| Dàoxìn (Dayi Daoxin) | 580–651 | Founded the first organized Chan monastic community; taught the Five Gates system. |

| Hóngrěn (Daman Hongren) | 601–674 | Expanded Chan teaching to larger monastic audiences; emphasized the Diamond Sūtra. |

The Early Chan Texts and the Rise of the Southern School

The Song of Enlightenment (Shōdōka in Japanese) is a classic Chan poem attributed (though with much scholarly debate) to Yǒngjiā Xuānjué (665–713), a disciple of Huìnéng, the Sixth Ancestor. Composed in the early seventh century CE, this text celebrates the realization of sudden awakening and the direct path of Chan practice.

Jìngjué (683–c. 750) compiled the Record of the Masters and Disciples of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra (Lengqie shizi ji), one of the earliest systematic records of the Chan lineage. This work includes a version of the Treatise on the Two Entrances and Four Practices (Erru Sixing Lun), attributed to Bodhidharma, with a preface by Tánlín (506–574), a disciple of either Bodhidharma or Huìkě.

The Treatise represents the earliest written record of Bodhidharma’s teachings, introducing essential Chan doctrines: non-duality, emptiness, and inherent Buddha-nature.

The Lengqie shizi ji also preserves a passage attributed to Dàoxìn that may be the earliest known account of Chan meditation technique.

Dàmǎn Hóngrěn (601–674), the Fifth Ancestor of Chan, trained under Dàoxìn from childhood. His teachings were later collected into the Treatise on the Essentials of Cultivating the Mind (Xiujing Yao Lun), which stands as the first known compilation of any Chan master’s ideas. In this work, Hongren emphasized meditative introspection, the innate purity of mind, and gradual cultivation toward enlightenment.

One of Hongren’s foremost disciples, Yúquán Shénxiù (606–706), referred to their lineage as the East Mountain Teaching. This school drew primarily upon the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra and the Prajñāpāramitā corpus but was also heavily influenced by the philosophical commentary Awakening of Faith in the Absolute (Dasheng Qixin Lun).

Although traditionally attributed to the Indian poet-philosopher Aśvaghoṣa, modern scholarship suggests it was likely composed by the Indian translator Paramārtha (499–569) or by an unknown sixth-century Chinese Buddhist. The Awakening of Faith became a cornerstone text for understanding Buddha-nature and mind-ground theory in early Chan.

The Southern Chan tradition arose with Huìnéng (638–713), the most famous of Hongren’s Dharma heirs and the recognized Sixth Ancestor of Chan Buddhism. Huìnéng’s teachings are preserved in the Platform Sūtra of the Sixth Ancestor (Liuzu Tanjing), traditionally credited to his disciple Fǎhǎi, although the text was composed and edited over time during the eighth century, probably under the influence of Huìnéng’s successor Hézé Shénhuì (684–758).

The Platform Sūtra advocates sudden awakening (dunwu) and emphasizes the direct realization of Buddha-nature without reliance on gradual practices. Along with the Heart Sūtra, the Platform Sūtra became one of the two core scriptures of the Chan tradition, soon to be followed by the later compilation of lineage records known as The Transmission of the Lamp (Jingde Chuandeng Lu).

The Great Masters of Chan

Shítóu Xīqiān (700–790), a prominent disciple of Huìnéng, composed the Song of the Grass-Roof Hermitage (Cáotáng Gē), a short and evocative poem describing the contemplative life of the hermit monk and the practice of Chan meditation in natural simplicity.

Shítóu also authored the Sandōkai (“Harmony of Difference and Equality” or “Harmony of the Relative and the Absolute”), a seminal text still chanted today in the Japanese Sōtō Zen tradition. The Sandōkai presents an elegant reflection on the interplay between unity and diversity, form and emptiness.

While the Caodong (Japanese: Sōtō) school traces its lineage back to Shítóu Xīqiān, the Línjì (Japanese: Rinzai) school descends from Mǎzǔ Dàoyī (709–788). In Mǎzǔ’s Extensive Records, the term “Chan school” (chánzōng) appears for the first time, signaling the growing identity of Chan as a distinct tradition within Chinese Buddhism.

Around the same period, the Daoist classic Qīngjìng Jīng (“Classic of Purity and Stillness”), composed by an unknown author in the ninth century, synthesized Daoist guān (observational meditation) with Buddhist vipassanā (insight meditation), reflecting the deep interplay between Chinese Daoism and imported Buddhist practices.

Dòngshān Liángjiè (807–869), known in Japan as Tōzan Ryōkai, founded the Caodong school of Chan Buddhism. Dòngshān is revered today as one of the most influential early figures in the lineage. His short poem The Five Ranks (Wuwei; Japanese: Go-i), inspired by the Yijing (I Ching) and possibly the Sandōkai, outlines a sophisticated vision of the dynamic relationship between absolute and relative reality, forming the doctrinal backbone of Caodong thought.

Another important text attributed to Dòngshān is The Jewel Mirror Samādhi (Baojing Sanmei; Japanese: Hōkyō Zanmai), a profound meditation poem further elaborating the Five Ranks philosophy. It remains a central liturgical chant in contemporary Sōtō Zen practice.

The Record of Dòngshān (Dongshan Yulu) preserves dialogues between Dòngshān and both his teachers and his students, providing valuable insights into early Caodong teaching methods and attitudes.

Foundational Texts and Sutras

The Śūraṅgama Sūtra (“Heroic March Sutra”), associated with Yúquán Shénxiù (606–706) and the East Mountain Teaching, reflects influences from Nāgārjuna, Yogācāra thought, tathāgatagarbha (Buddha-nature) doctrine, and emerging Vajrayāna ideas. This sutra became highly influential within the Chan tradition, later referenced in the Blue Cliff Record (Case 94) and cited by Dōgen in his Shōbōgenzō, Chapter 71: Turning the Dharma Wheel (Tenborin).

The great Indian scholar Śāntideva (8th century CE) composed the Bodhicharyāvatāra (“The Way of the Bodhisattva”), a classic work outlining the six-fold practice of the bodhisattva path: carefulness, vigilant introspection, patience, diligence, meditative concentration, and wisdom. While especially revered in Tibetan Buddhism, its influence spread widely across Mahāyāna traditions.

Later Historical Compilations

In 982 CE, Zànníng (919–1001) compiled the Song Biographies of Eminent Monks (Song Gaoseng Zhuan) on behalf of the emperor, preserving accounts of the most notable Buddhist monks of the Song dynasty.

The monumental Jìngdé Record of the Transmission of the Lamp (Jìngdé Chuándēng Lù), compiled between 1004 and 1007 CE, spans thirty volumes and remains one of the most important historical records of the Chan lineage. This work systematically traces the transmission of Chan insight from master to disciple across generations.

The Great Compassion Dhāraṇī Sūtra, also known as the Mahā Karuṇā Dhāraṇī Sūtra or the Nīlakaṇṭha Dhāraṇī Sūtra, is an important devotional text in Chinese Buddhism, recited in both Rinzai and Sōtō Zen traditions. It is a liturgical invocation associated with Avalokiteśvara (Guānyīn in Chinese; Kanzeon/Kannon in Japanese), the bodhisattva of compassion. The dhāraṇī was translated into Chinese by Bhagavaddharma in the seventh century and by Amoghavajra in the eighth century, blending Buddhist and earlier Indian religious imagery of the thousand-armed, thousand-eyed compassionate protector.

These great masters and texts shaped the doctrinal, poetic, and devotional currents of classical Chan Buddhism.

Great Masters of Chan and Key Contributions

| Master | Dates | Key Contribution or Text |

| Shítóu Xīqiān | 700–790 | Song of the Grass-Roof Hermitage; Sandōkai; early Caodong lineage |

| Mǎzǔ Dàoyī | 709–788 | Founder of the Línjì (Rinzai) line; first use of “Chan school” term |

| Dòngshān Liángjiè (Tōzan Ryōkai) | 807–869 | Founder of Caodong school; Five Ranks; Jewel Mirror Samādhi |

| Yúquán Shénxiù | 606–706 | East Mountain Teaching; Śūraṅgama Sūtra influence |

| Śāntideva | 8th century CE | Bodhicharyāvatāra (“The Way of the Bodhisattva”) |

| Zànníng | 919–1001 | Song Biographies of Eminent Monks (Song Gaoseng Zhuan) |

| Compilers of Transmission of the Lamp | 1004–1007 CE | Jìngdé Record of the Transmission of the Lamp; chronicle of Chan lineage |

| Bhagavaddharma and Amoghavajra | 7th–8th centuries CE | Translations of the Great Compassion Dhāraṇī Sūtra (Mahā Karuṇā Dhāraṇī) |

Silent Illumination and the Rise of Koan Practice

Hóngzhì Zhèngjué (Japanese: Wanshi Shōgaku, 1091–1157) was a prominent Chan master and abbot of Tiāntóng Monastery on Taibai Mountain in Yinzhou District, Ningbo, Zhejiang Province, China.

He became highly influential for advocating Silent Illumination Chan (mòzhào chán; Japanese: mokusho zen), a method emphasizing open, non-conceptual awareness without striving or deliberate focus.

Hóngzhì’s major contribution, the Book of Equanimity (also known as the Book of Serenity), became a central text of the Caodong school, solidifying Silent Illumination as its predominant form of meditation. His teachings, informal talks, sermons, recorded sayings of earlier masters, and poetry were compiled into the extensive nine-volume Record of Chan Master Hongzhi (Hóngzhì Chánshī guǎnglù).

Eihei Dōgen (1200–1253), the founder of the Japanese Sōtō Zen school, trained under Tiāntóng Rújìng, a successor in Hóngzhì’s lineage, at Tiāntóng Monastery. Dōgen’s thought and style were profoundly influenced by the Silent Illumination tradition he encountered there.

The Linji Tradition and the Development of Koan Practice

The Record of Línjì (Línjì yǔlù; Japanese: Rinzai-goroku or Record of Rinzai) preserves the teachings and sayings of Línjì Yìxuán (Japanese: Rinzai Gigen), the founder of the Línjì (Rinzai) school of Chan Buddhism. The classic version, Zhenzhou Linji Huizhao Chansi Yulu, was compiled by Yuánjué Zōng’àn in 1120 CE and remains one of the most important records of early Chan rhetoric, style, and methods.

Dàhuì Zōnggǎo (1089–1163), a major figure in the Linji lineage, rejected the growing popularity of Silent Illumination Chan. Instead, he developed and championed Kànhuà Chan (“Investigating the Critical Phrase”), a dynamic meditation practice focused on the concentrated inquiry (kan huàtou) into a pivotal word or phrase related to a koan (gong’an, “public case”). This method sharpened awareness and encouraged sudden breakthroughs.

The Kanhua approach evolved alongside the development and use of koan collections, which became fundamental to Linji practice:

- The Blue Cliff Record (Bìyán Lù, 1125) — Compiled by Yuánwǔ Kēqín (1063–1135) of the Linji school; later commented upon by Dàhuì.

- The Book of Equanimity (Congrong Lu, 1223) — Compiled by Hóngzhì Zhèngjué and edited by Wànsōng Xìngxīu (1166–1246) of the Caodong school.

- The Gateless Gate (Wúmén Guān, 1228) — Compiled by Wúmén Huìkǎi (1183–1260) of the Linji school.

These collections not only preserved the sayings and encounters of Chan masters but also structured them into systematic aids for meditation and realization. Together, Silent Illumination and Kanhua represented two great and complementary streams within the maturing Chan tradition.

Chan Monastic Codes

The foundation of Chan monastic life was firmly rooted in the broader Buddhist monastic tradition, particularly the vinaya (disciplinary codes).

The first vinaya to be translated into Chinese was the Ten Recitation Vinaya (Sarvāstivāda Vinaya), rendered into Chinese by Kumārajīva in the fourth century CE.

More influential for the Chan tradition, however, was the Four-Part Vinaya (Caturvargika Vinaya; Chinese: Sìfēn Lǜ) of the Dharmaguptaka school, translated into Chinese by the Kashmiri monk Buddhayaśas in the fourth century. The Four-Part Vinaya remains the standard monastic code followed by Chan, Zen, and other East Asian Buddhist schools today.

Early Chan Monastic Adaptations

Guīshān Lìngyòu (771–853), a disciple of the great Chan master Bǎizhàng Huáihǎi, authored the Guishan’s Admonitions (Guīshān Jìngcè), which illustrates that early Chan monasteries remained well within the established Buddhist vinaya framework even as they developed distinctive practices.

The earliest extant Chan-specific monastic code is the Teacher’s Regulations (Shī Guīzhì), composed by Xuěfēng Yìcún (822–908) around 901 CE. This document reflected the emerging need to tailor vinaya regulations to the specific realities of Chan communal life.

The Pure Rules of Baizhang and the Codification of Chan Monasticism

According to later tradition, the Pure Rules of Bǎizhàng (Baizhang Qinggui) were compiled in the eighth century under the direction of Bǎizhàng Huáihǎi. This legendary code is often credited as the first comprehensive monastic regulation designed specifically for Chan monasteries, a significant step in the sinicization of Buddhist monastic practice. However, modern scholars generally agree that the original Pure Rules text has been lost and likely never existed in the complete form described in later sources.

Instead, the Rule of the Chan Gate/Monastery (Chánmén Guīshì), compiled in the ninth or tenth century, appears to have served as a working synopsis of these early regulations. The Chanmen Guishi was published alongside Baizhang’s biography in the Record of the Transmission of the Lamp (Jìngdé Chuándēng Lù, 1004). A fuller version was preserved within the Chányuán Qīngguī (“Rules of Purity for the Chan Monastery”) in 1103, and a commentary was included in the Imperial Edition of the Baizhang Code published in 1336 during the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368).

The Chanyuan Qinggui and the Chan Monastic Ideal

The Chányuán Qīngguī (Rules of Purity for the Chan Monastery), compiled by Chánglú Zōngzé (d. c. 1107) in 1103, became the definitive monastic code for Chan communities. Also known as the Monastic Regulations of the Zen Garden, this text regulated every aspect of communal life—from daily schedules and etiquette to meditation practice and monastic governance. Although initially believed to be the earliest extant Chan code, it built upon previous, now-lost regulations such as the Pure Rules of Baizhang.

The Zuòchán Yí (“Manual of Seated Meditation”), also attributed to Chánglú Zōngzé, represents the earliest surviving written instruction for Chan meditation (zuòchán). This concise meditation manual profoundly influenced later figures, most notably Eihei Dōgen, whose Fukanzazengi (“Universal Recommendation for Zazen”) reflects its structure and spirit.

The development of Chan monastic codes reflects the adaptation of early Buddhist discipline to the distinctive communal and meditative life of Chan monasteries.

Major Chan Monastic Codes

| Monastic Code | Compiler | Date | Key Contribution |

| Ten Recitation Vinaya | Kumārajīva | 4th century CE | First vinaya translated into Chinese (Sarvāstivāda tradition). |

| Four-Part Vinaya (Sìfēn Lǜ) | Buddhayaśas | 4th century CE | Dharmaguptaka vinaya; standard code for Chan and East Asian Buddhism. |

| Guishan’s Admonitions | Guīshān Lìngyòu | 8th–9th century | Demonstrated Chan integration within traditional vinaya. |

| Teacher’s Regulations (Shī Guīzhì) | Xuěfēng Yìcún | 901 CE | Earliest extant Chan-specific regulations. |

| Rule of the Chan Gate/Monastery (Chánmén Guīshì) | Anonymous | 9th–10th century | Summary of early Chan rules; connected to Baizhang tradition. |

| Chányuán Qīngguī (Rules of Purity) | Chánglú Zōngzé | 1103 CE | First comprehensive Chan monastic code; detailed rules for daily life. |

| Zuòchán Yí (“Manual of Seated Meditation”) | Attributed to Chánglú Zōngzé | Early 12th century | Oldest surviving meditation manual for Chan practice. |

The Literature of Japanese Zen

Japanese Rinzai (Linji) Zen

The Rinzai school (Japanese: Rinzai-shū), tracing its lineage back to the Chinese Línjì tradition of Línjì Yìxuán (Rinzai Gigen), flourished in Japan especially from the Kamakura period (1185–1333) onward. Its literature reflects the energetic, confrontational style of Linji teaching, emphasizing sudden insight (kenshō) often sparked by dynamic interaction, paradox, and the use of kōans.

Core Texts and Anthologies

The most characteristic literary expression of Rinzai Zen is the kōan collection—curated stories and dialogues that encapsulate critical moments of realization. Major Rinzai Zen texts include:

- The Blue Cliff Record (Hekiganroku) — A collection of one hundred kōans originally compiled in China (1125 CE) and later introduced to Japan. It became a major text for Rinzai monks, with elaborate commentaries and verses appended for meditation and study.

- The Gateless Gate (Mumonkan) — Compiled by Wúmén Huìkǎi (Japanese: Mumon Ekai) in 1228. The Mumonkan presents forty-eight kōans, each accompanied by Mumon’s succinct commentary and verse, emphasizing direct penetration beyond conceptual thought.

- The Record of Linji (Rinzai-roku) — The sayings and sermons of Línjì Yìxuán himself, advocating fierce independence, intuitive action, and “grasping the mind at its root.” This became a foundational scripture for Japanese Rinzai training.

- The Book of Serenity (Shōyōroku) — Although compiled in the Caodong (Sōtō) tradition, it was studied by Rinzai monks as well. Its presentation is more serene and poetic, contrasting with the explosive style of the Blue Cliff Record.

Monastic Literature and Kōan Commentaries

In medieval Japan, Rinzai masters developed a rich body of kōan commentary literature to aid monks in their formal training (kōan rōhatsu practice). This literature includes:

- Formal commentaries (kirigaki) appended to each kōan.

- “Checking points” (sassu) used by teachers to probe the student’s realization.

- Verses (jakugo) composed as poetic responses to kōans.

Such works emphasized personal encounter dialogue (mondō) as the vehicle of realization, requiring the student to respond with immediacy and authenticity rather than rational analysis.

Key Rinzai Figures in Japan

Prominent Japanese Rinzai masters who contributed to the school’s literary tradition include:

- Eisai (1141–1215) — Founder of the Rinzai school in Japan; wrote Kōzen Gokokuron (“Promoting Zen to Protect the Nation”), advocating Zen as a stabilizing force for society.

- Enni Ben’en (1202–1280) — Founder of Tōfuku-ji monastery; transmitted the vigorous Linji style.

- Hakuin Ekaku (1686–1769) — Revitalizer of Rinzai Zen; compiled and systematized the kōan training curriculum, composing numerous commentaries and influential works like Orategama (“The Idle Talk Furnace”) and Yasenkanna (“Night Boat Dialogue”).

Hakuin emphasized intense doubt (great doubt, daigi) and relentless inquiry into kōans, reshaping Rinzai Zen into the rigorous form still practiced today.

Ikkyū Sōjun: The Wild Zen Poet

Ikkyū Sōjun (1394–1481) was an iconoclastic Japanese Zen monk, poet, and artist associated with the Rinzai school of Zen. Renowned for his rebellious spirit, irreverent humor, and fierce devotion to authentic Zen realization, Ikkyū rejected the rigid formalism and political entanglements of the Zen establishment of his time.

A maverick figure, Ikkyū lived much of his life as a wandering monk, frequenting teahouses, brothels, and the countryside, seeing enlightenment not in monastic purity but in the rawness of everyday experience. His poetry, composed in vernacular Chinese and Japanese, blends biting social critique, profound meditative insight, sensuality, and flashes of comic absurdity.

Ikkyū’s most famous poetry collection, Kyōunshū (“Collection of Crazy Cloud”), offers a vivid glimpse into his fiercely individualistic view of Zen—a Zen rooted in both emptiness and earthy compassion. Today, Ikkyū remains celebrated not only as a Zen master but as a cultural hero who embodied the wild, untamed spirit of true awakening.

Japanese Sōtō (Caodong) Zen

Foundations of Zen in Japan

Myōan Eisai (1141–1215), initially ordained in the Tendai tradition, traveled to China where he received training in the Línjì (Rinzai) school of Zen. Upon his return to Japan in 1191, Eisai founded Hōon-ji Temple in Kyushu, Japan’s first Zen temple.

In order to secure official recognition for Zen Buddhism, Eisai wrote the Treatise on the Propagation of Zen for the Protection of the State (Kōzen Gokokuron), emphasizing Zen’s role in strengthening the nation’s spiritual foundation.

Eihei Dōgen (1200–1253), after training at Kennin-ji under Eisai’s successors, journeyed to China where he studied under Tiāntóng Rújìng of the Caodong school. Upon returning to Japan, Dōgen became the true founder of Sōtō Zen. He introduced the practice of zazen (seated meditation) through works like the Fukanzazengi (“Universally Recommended Instructions for Meditation”), one of the earliest texts to formally present meditation instructions in Japanese Zen.

Dōgen’s Literary Legacy

Dōgen authored several foundational texts that shaped Sōtō Zen:

- Eihei Shingi (“Pure Standards for the Zen Community”) — Dōgen’s monastic code, regulating daily life in Zen monasteries according to his vision of strict discipline and continuous meditation.

- Shōbōgenzō (“Treasury of the True Dharma Eye”) — Dōgen’s magnum opus, a series of sermons and essays written in Japanese (Kana Shōbōgenzō) that articulate profound teachings on practice, realization, time, being, and the nature of reality.

- The term Shōbōgenzō originally referred to an earlier collection of kōans compiled during the Chinese Song dynasty (Zhengfa Yanzang), but Dōgen’s works completely redefined its significance in Japan.

- The term Shōbōgenzō originally referred to an earlier collection of kōans compiled during the Chinese Song dynasty (Zhengfa Yanzang), but Dōgen’s works completely redefined its significance in Japan.

- Shinji Shōbōgenzō — A collection of 300 kōans compiled by Dōgen without his extensive commentaries.

- Shōbōgenzō Zuimonki (“Record of Things Heard”) — A collection of Dōgen’s informal talks, compiled by his disciple Koun Ejō (1198–1280), offering a more accessible and practice-oriented presentation of his teachings.

- Eihei Kōroku (“Extensive Record of Eihei Dōgen”) — A ten-volume compilation of Dōgen’s formal Dharma talks (jōdō), informal meetings (shōsan), letters (hōgo), poetic verses, and kōans, reflecting the breadth of his mature teaching.

Transmission and Expansion

Koun Ejō, Dōgen’s closest disciple and the Second Ancestor of Sōtō Zen, not only preserved Dōgen’s oral teachings (Zuimonki) but also continued the careful transmission of the school’s practice style.

Keizan Jōkin (1268–1325), often regarded as the “Second Founder” of Sōtō Zen in Japan, systematized and expanded the school’s monastic network. His important works include:

- Zazen Yōjinki (“Instructions on How to Practice Seated Meditation”) — A concise manual on the essentials of zazen.

- Denkōroku (“Transmission of the Light”) — A collection of Dharma transmission stories tracing the lineage from Śākyamuni Buddha to Dōgen and Koun Ejō.

Meihō Sotetsu (1277–1350), a direct student of Keizan and the Fifth Ancestor of Sōtō Zen, produced important teachings including a famous sermon on zazen practice.

Later Commentarial Tradition

Dōgen’s disciple Senne helped publish the first organized edition of the Shōbōgenzō in 1263, containing seventy-five fascicles, accompanied by his own (now lost) commentary and that of Kyōgō, another of Dōgen’s close students.

- Kyōgō’s commentary was later expanded into the Gokikigakishō (“Collected Records of Things Heard”), which became a major source for later generations of Dōgen scholars.

This work heavily influenced the Edo-period scholars Menzan Zuihō (1683–1769) and Banjin Dōtan (1698–1775), whose studies helped solidify the centrality of Dōgen’s writings in the Sōtō school.

Giun (c. 1200–after 1299), a disciple of Jakuen (a Chinese companion of Dōgen who remained in Japan), composed the earliest known poetic commentary on the Shōbōgenzō.

Giun’s work, along with his own recorded sayings (Giun Goroku), kept the flame of Dōgen’s teachings alive until a fuller revival centuries later with figures like Tenkei in the 17th century.

These masters preserved, expanded, and transmitted Dōgen’s vision, shaping the distinctive character of Japanese Sōtō Zen.

Major Figures in Japanese Sōtō Zen