Revised 2025

Inside Monastic Culture Part I

The Solitaries

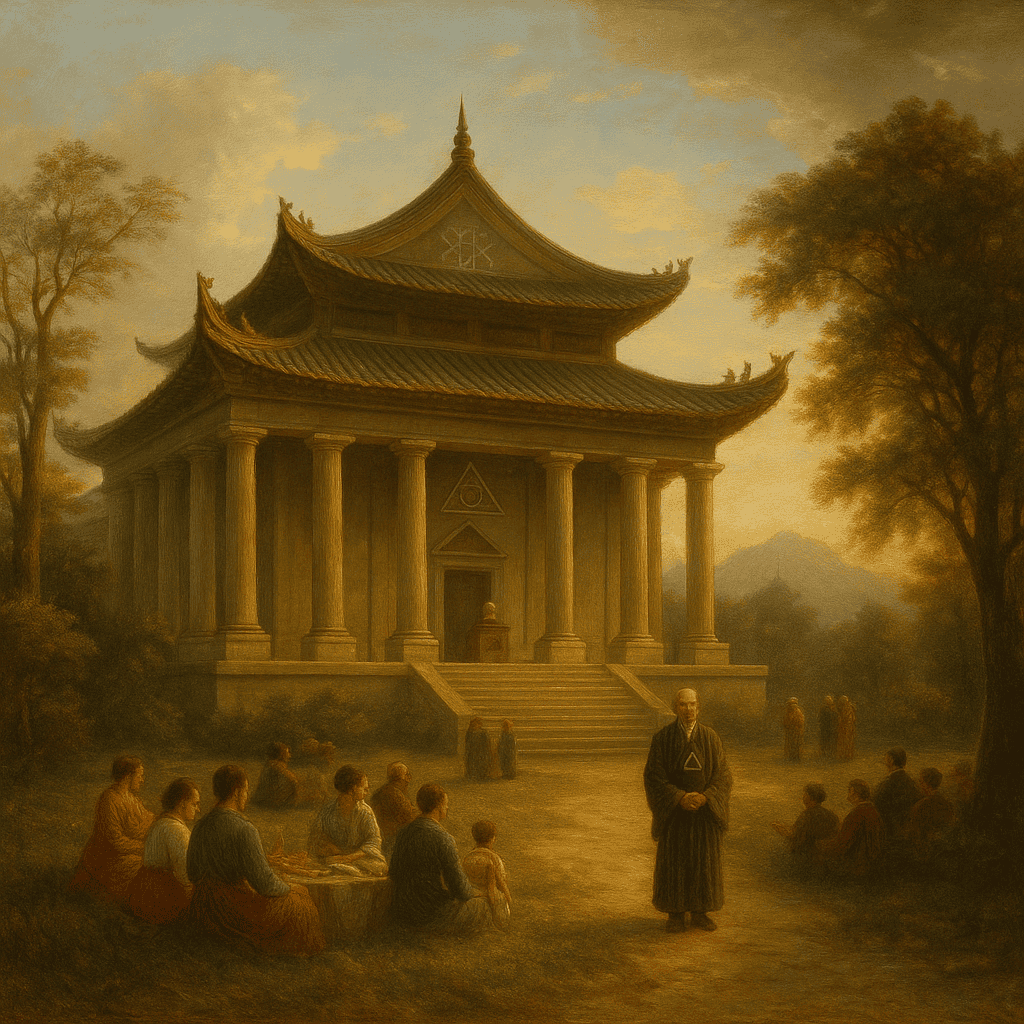

The Science Abbey website is so named as it is inspired by science, the method of understanding reality, and monastic culture, a life of devotion and contemplation. The subject of monasticism relates to monks, nuns and their sanctuary, the monastery. This article is a brief introduction and practical guide to the basics of monasticism to orient the reader to this fascinating and enlightening way of life.

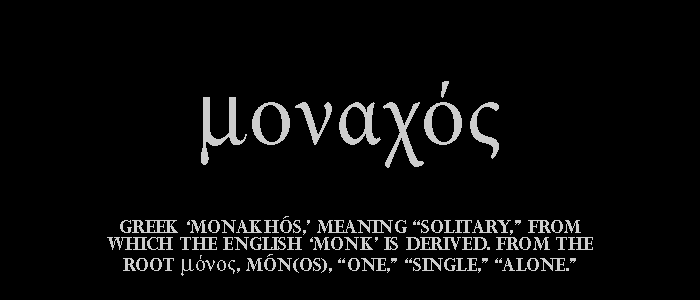

The word ‘monk’ is of ancient Greek origin, μοναχός, monakhós, literally meaning “solitary,” from the root μόνος, món(os), “one,” “single,” “alone.”

A Christian monachos, or hermit, was a man or woman who renounced married life to pursue a life of solitude and contemplation. The Medieval Latin and Late Latin monachus became munuc in Old English around the fifth century and monk in Middle English sometime before the tenth century.

In modern English “monk” refers to a man; the equivalent term for a woman is “nun,” from the Old English nunne, “priestess” or “nun,” from the Late Latin nonna, “tutor,” “nun” or “grandmother.” The terms “monk” and “nun” can be used for monastics of any religious denomination.

The Nun

With few exceptions, such as the lofty stations of certain Hindu and Christian saints, the status of women has typically suffered from bigotry within their religious traditions. Jewish women were not ordained as rabbis until the 1970s.[1] Even the Roman Catholic nun is refused the position of priest because of her gender.

Menstruating Hindu women are considered impure and not allowed to worship within the temple (although there are different explanations for this convention).[2] Only Brahman (priestly) males are allowed to perform Vedic religious ritual.

The institution of the Buddhist nun (in Sanskrit bhiksuni and in Pali bhikkhuni) was created at the same time as the monk (Sanskrit bhikṣu and Pali bhikkhu) during the sixth to fifth centuries BCE in the time of the Buddha. The nuns have many more rules to follow in relation to the monks; there are 227 precepts for monks[3] and 311 for nuns.[4]

In many countries women may only become novices who serve the men. In Thailand and Burma women are simply prohibited from ordination.[5]

Traditionally, and in most religious monastic cultures even today, cultural and institutional misogynistic attitudes placed nuns at a lower status than their male counterparts. In an organization established for the purpose of solitary contemplation and chastity, it makes sense to separate genders, but there is no scientific reason to discriminate against one gender in terms of hierarchical rank. In fact, the opposite is true.

More gender equal communities have been shown to be more productive than discriminatory cultures.[6] [7] In societies where women are discriminated against, science shows that men do score higher on cognitive tests, but the same tests show that women are slightly more intelligent than men in nations with higher levels of gender equality.[8]

Stephen Hawking dismisses the idea that scientific tests are needed as evidence of the equality of the genders; the great physicist points to the growing success of women as proof enough of the absurdity of sexist attitudes.[9]

Forbes Annual List of the Most Powerful Women

Most Influential Women in History

Orders and the Priesthood

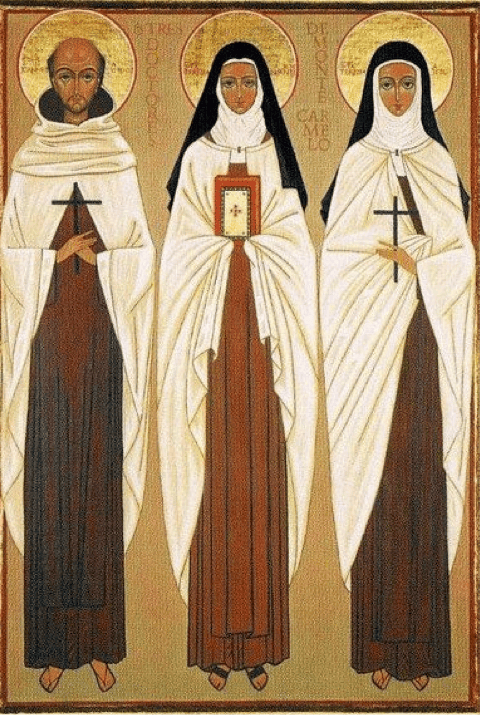

In the Christian world women’s monastic orders are known as the second orders. The second orders arose in the Middle Ages with the Roman Catholic mendicant orders of friars.

As laity joined in the activities of the mendicant orders, they were allowed to identify with an order without taking the monastic vows, and came to be known as the third orders or tertiaries, from the Latin tertiarii, from tertius, third. Groups of tertiaries sometimes formed congregations at their own place of meeting, becoming what are known as the third order regular.

Monastics may be sacerdotal or non-sacerdotal. Christian priests may be monks, but traditionally priests may not be women or, by extension, nuns. The various denominations have different policies regarding the ordination of women.

Technically, neither Judaism nor Islam has priests, but the equivalents are the Jewish rabbi and the Muslim imam. Women were not ordained as rabbis until the 1970s and women are not allowed to be imams, although a new movement is challenging that.

Neither Judaism nor Islam allows monasticism per se. However, members of the Muslim Sufi order, a mystical sect, may retreat to solitary contemplation and return to ordinary life.[1] Judaism has its own contemplative practices that sometimes lead to solitude.[2]

In the Vedic tradition of ancient India, two distinct yet complementary spiritual roles emerged: the Vedic priest (“purohita”) and the Vedic monastic (“sannyasi”). Though both pursued spiritual knowledge and sacred discipline, their lifestyles and purposes diverged significantly.

The “Vedic priest” was primarily a householder, integrated into society and responsible for performing ritual sacrifices (“yajnas”), chanting Vedic hymns, and maintaining the sacred rites for kings, nobles, and communities. Priests preserved the oral transmission of the Vedas and served as the religious functionaries of the early Vedic civilization.

By contrast, the Vedic monastic renounced social obligations, material possessions, and ritual duties in favor of a solitary life devoted to meditation, self-inquiry, and the realization of ultimate truth (“Brahman”). These sannyasis were often wanderers who sought liberation (“moksha”) through introspection and direct experience, rather than through ritual performance.

Whereas the priest sought divine favor through ceremony and tradition, the monastic sought transcendence beyond the world of forms and rites. Together, they reflect the dual paths within the Vedic worldview—”action through sacred duty”, and “liberation through renunciation.”

Buddhism does not ordain priests as a separate function to serve the lay community, as Christianity does. The Buddhist monk/priest (Sanskrit bhikṣu and Pali bhikkhu) and nun/priest (Sanskrit bhiksuni and Pali bhikkhuni) may serve the lay community while staying at the monastery, or in association with a Buddhist temple or center, or they may be solitary.

In today’s global landscape, Zen priesthood takes on many forms—some ancient and ascetic, others modern and adaptive—shaped by the historical, cultural, and legal contexts in which Zen is practiced. From the strict monastic codes of China to the married clergy of Japan, and the emerging hybrid models in Europe and the United States, the role of the Zen priest today reflects both the durability and the adaptability of Buddhism in a changing world.

China: Upholding the Classical Monastic Tradition

In contemporary China, Zen (Chan) priesthood retains much of its classical character. Monastics, both bhikkhu (monks) and bhikkhuni (nuns), undergo full ordination and take on hundreds of detailed precepts—over 250 for men and 311 for women. These rules cover every aspect of daily life, from robes and hygiene to rigorous celibacy, dietary restrictions, and the renunciation of personal property.

Zen monasteries in China are highly disciplined environments, preserving a lineage that dates back to the Tang and Song dynasties. These monastics often live communally, depend on alms or temple support, and dedicate their lives to meditation, liturgy, study, and public service. The model closely mirrors the original vinaya system upheld since the Buddha’s time and is considered a living embodiment of Buddhist orthodoxy.

Japan: A Modern Clerical Model

The use of the term “Zen precepts,” are considered to have developed during the Tokugawa period (1603-1868). Zen priesthood in Japan underwent radical transformation during the Meiji era (1868–1912), when the government enforced policies to suppress Buddhism and encourage modernization. As a result, Japanese Zen eliminated the traditional bhikkhu sangha, replacing full ordination with a streamlined system based on the traditional 16 Bodhisattva precepts.

This shift opened the way for Japanese Zen priests—especially male priests—to marry, raise families, and even consume alcohol and meat. The result was a clerical model centered on the family temple system, in which priesthood is often hereditary and temple maintenance becomes as much a civic duty as a spiritual one.

While some criticize this model for diluting monastic discipline, others praise it for integrating Zen into the rhythms of everyday Japanese life. Female priests, however, usually remain celibate and continue to live in monastic communities, preserving a more traditional orientation.

Europe and the United States: A Synthesis of East and West

In Europe and the United States, Zen priesthood is still relatively young and experimental. Here, many sanghas (communities) look to Japanese Soto or Rinzai models for inspiration, but adapt their practices to Western cultural values—such as gender equality, lay participation, and psychological insight.

Ordained Zen priests in the West often hold day jobs, live outside monasteries, and are encouraged to balance spiritual discipline with family life and civic engagement. While many Western Zen teachers have taken the 16 Bodhisattva precepts in the Japanese tradition, there is a growing interest in reconnecting with the full vinaya as practiced in China and Southeast Asia.

In the English-speaking world, a distinction is often drawn between “monks” and “priests”, to clarify whether an ordained person is celibate or not. However, such labels are still fluid, and in many sanghas, the term “priest” refers broadly to any ordained person who has committed to a life of service, regardless of marital status.

What Does It Mean to Be a Zen Priest Today?

Across the globe, Zen priesthood continues to evolve. In some places, it is a life of strict renunciation and communal meditation; in others, a hybrid path of teaching, parenting, and spiritual leadership in lay society. While the form varies, the essence remains: a vow to live by the Dharma, to practice and uphold ethical precepts, and to serve all beings with compassion and wisdom.

As Zen continues to root itself in new cultures, priesthood becomes not just a role but a dynamic conversation—between East and West, between tradition and innovation, between monastic discipline and lay engagement.

It is not uniform, but it is authentic, shaped by lineage and lived experience, and deeply committed to the transformation of self and society. In every corner of the world, the Zen priest is a reflection of the Dharma—adaptable, responsive, and awake.

In the native Japanese Shinto religion Japanese monks may also serve as priests.

When monastics congregate together they form a variety of communal association, the nature of which, in relation to other fraternal organizations, is interesting to consider and informative of human nature.

There are several general types of monk or nun that have arisen throughout history, which will be described in this, and the other articles, in the Monastic Culture Series. This list includes hermitic or eremitic, anchorite, quasi-eremitic, cenobitic (coenobitic), quasi-monastic, mendicant and friar.[3]

Let’s begin with the earliest kind of monk, the hermit.

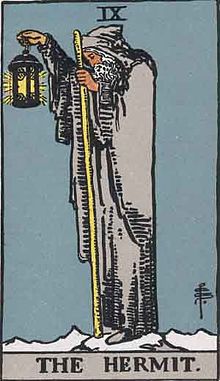

The Hermit

The hermit exists in a kind of timeless vacuum, withdrawn from society, absorbed in contemplation of the eternal. This is the life of the eremitic monk through the ages. Considering human nature and the sophistication of ancient Egyptian, Middle Eastern and Asian societies, it is likely that contemplative hermits lived from the earliest times, even before the dawn of civilization and into the darkness of prehistory. The first monks and nuns were hermits.

The first hermits were the poet rishis (“seers” or “sages”) of lore in the Indian scriptures like the Vedic Rigveda (1700 – 1100 BCE), the Mahabharata and later Hindu texts. The rishis meditated on the eternal to become illuminated and liberated from worldly concerns, imparting their insight and wisdom in inspired hymns.

The Jain shramanas or “ascetics” began their religious tradition in the sixth century BCE. The Chinese Classic of Poetry composed mostly during the Western Zhou period (1046–771 BCE) first mentioned the legendary xian or mountain immortals, precursors of the early Han Dynasty (third century BCE) Daoist recluses.

The sixth – fifth century BCE Gautama Buddha and his early disciples were mendicant (beggar) hermit monks and nuns who met together only during the rainy season. In time many Buddhists began living communally permanently in monasteries, but the hermit tradition survived, as well. In China, Daoist and Buddhist traditions evolved in parallel, preserved by and centered on eremitic and cenobitic monks.

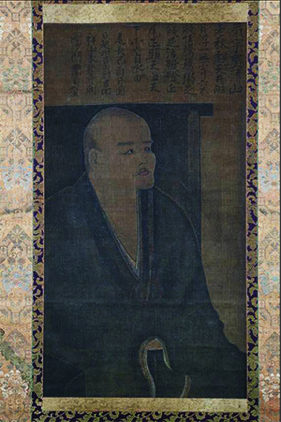

Bodhidharma was an Indian Buddhist monk who migrated to China in the sixth century CE. He studied at the Shaolin monastery and developed Chan (Japanese Zen) Buddhism. Bodhidharma, also known as Damo, meditated facing the wall of a cave near the temple for nine years.

Other renowned Buddhist hermits include the ninth century Chinese Daoist and Chan Buddhist Hanshan and the Japanese Soto Zen Buddhist monk Ryōkan Taigu (1758–1831).

The hermit or eremite is a recluse. Hermitic, or eremitic monasticism, is a form of solitary monasticism. This kind of monk or nun renounces worldly pursuits and withdraws from society. They often take a vow of poverty and celibacy, devoting their lives to isolated prayer and meditation.

The English words ‘hermit’ and ‘hermitic,’ like the noun ‘eremite’ and adjective ‘eremitic,’ derive from ‘ĕrēmīta,’ the latinisation of the Greek erēmitēs, “of the desert,” or “desert-dweller,” related to the Greek ‘erēmos,’ meaning “desert” or “uninhabited.”

The First Christian Monks

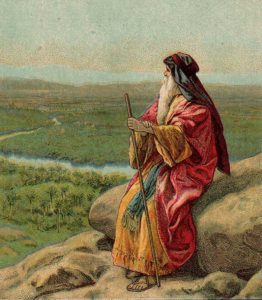

Christian monastics have often been inspired by the desert spirituality inherent in the Judeo-Christian tradition. The Hebrew scriptures are based on the “desert theology” of the legendary lawgiver of the Israelites, Moses. Moses was said in the Book of Exodus to have led his people through the desert for forty years, wandering and waiting to be delivered by their Creator and Lord god Yahweh to the Promised Land of Israel.

The Christian gospels* expand on this desert spirituality when the savior Jesus (Yeshua) of Nazareth withdraws to the desert wilderness to fast for forty days and nights. He is guarded by angels and is to be tested or tempted into sin by the devil Satan. Jesus overcomes Satan by renouncing earthly and supernatural powers, and swearing to obey and worship Yahweh, his divine father and higher self.

The first Christian monks were the Coptic Egyptians known as the Desert Fathers. Paul the Hermit, also known as Paul of Thebes and Paul the Anchorite, was the first known Christian monk. Paul was born in Egypt in the fourth century CE and lived under the religious persecution of the Roman Empire.

When he was fifteen he was orphaned and fled to the desert, coming to live in a cave, which earned him a reputation as a Christian recluse. Anthony of the Desert (252 – 356 CE) visited him, became his disciple, and buried him when he died. Paul’s biographer was Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus, otherwise known as Saint Jerome, the translator of the Holy Bible into the Latin Vulgate.

Anthony of the Desert, Anthony of Thebes, or Anthony the Great as he came to be known, became the ultimate inspiration to Christian hermitic monks. Anthony followed in the footsteps of Saint Paul the Hermit. His biographer was his friend Athanasius of Alexandria.

Anthony gained followers who began living as solitary monks in the desert around him. In time, these Christian ascetics in the Egyptian desert would naturally form small, informal communities.

* Matthew 4:1-11; Mark 1:12-13; Luke 4:1-13

The Solitary and the Monastery

While Christian monks first lived in natural caves or built small cells for their hermitages, they often attracted visitors seeking spiritual counsel and would-be disciples. Desert Fathers were known to weave baskets to trade for bread or other necessities.

In the Middle Ages Christian hermits lived nearby villages and cities as gatekeepers or ferrymen, and in the country they might be found as guides, light-bearers, bridge wardens or laborers.[1]

The different Catholic orders have various customs regarding living arrangements. Solitary hermits may live under the normally communal Benedictine or Franciscan rules. The Cistercians, Trappists and Carmelites allow monks and nuns who have experienced years of communal life to inhabit a private cell within the monastic estate if they are called to the eremitic lifestyle. The Carthusians and Camaldolese live in small groups of hermitages and meet occasionally for communal prayer, meals, or other activities.

The ‘Institutes of Consecrated Life’ section of the Canon Law[2] of the Roman Catholic Church recognizes diocesan (territorial) hermits under the jurisdiction of a bishop.[3] The Code of Canons of Oriental Churches allows for hermits and ascetics under ‘Title 12: Monks and Other Religious as well as Members of Other Institutes of Consecrated Life,’ canons 481 – 485.[4]

Eastern Orthodox churches permit only one type of monasticism, called Tonsure, as described in the Euchologion, wherein the aspiring monk or nun passes through novitiate and three degrees in conferring the monastic habit. These monastics are regularly referred to as hermits, although they live as cenobites, as their monasteries may exist physically distant from society.

The Episcopal Church Constitution and Canons provides for solitaries under its ‘Religious Orders and Other Christian Communities’ canon: Title 3, canon 14, section 3.[5]

The Anchorite

There are two types of solitary: the hermit and the anchorite. The ancient Greek anachōrētḗs was “one who has retired from the world.” Christian anchorites are known to have existed as early as the third century CE and flourished in the early and high Middle Ages. The anchorite or anchoress answered only to the bishop of their diocese and was considered more important than a monk or nun.

The anchorite was consecrated in a rite comparable to a funeral rite to symbolize that they were leaving the world behind in an allegorical death. Whereas the hermit could live where he or she chose, an anchorite or anchoress took a vow to remain in a small cell that was anchored to a church, called an anchorhold. The anchorite was meant to stay in his cell under all circumstances.

The anchorage or anchorhold was a single cell with three windows, usually no larger than fifteen feet square, attached to the local church. One window faced the outdoors and served as a source of light. Caretakers used another window to transfer material necessities like food and drink to the anchorite.

One window, the “hagioscope” or “squint,” faced toward the sanctuary of the church to allow the anchorite to receive Communion, make Confession, observe services and speak to visitors who may seek advice. Within the cell was a bed, an altar and a symbolic crucifix.

The door of the anchorage was often locked or even absent altogether. A grave may be dug outside of a window to serve as a memento mori, “remember you are mortal,” where the anchorite would be buried upon death.

The anchorite or anchoress was vowed to a life of fasting, poverty and chastity, wearing coarse clothes, eating mostly vegetarian meals, and spending most of their time in prayer. He or she might write or illuminate manuscripts, illumination being mainly a man’s occupation. The anchoress might practice embroidery for the church or to be sold as a relic made by holy hands.

Read the thirteenth century The Ancrene Wisse or The Ancren Riwle:

A Treatise on the Rules and Duties of Monastic Life

Bound Together by Fellowship

Proto/semi/quasi-eremitic (or hermitic) or proto/semi/quasi-monastic monasticism refers to any living arrangement that falls partway between eremitic and cenobitic, or hermetic and monastic. This situation arises when hermits not bound by any formal rule or organization settle in proximity to each other and meet periodically for communal activities.

The early Buddhist community is an example of this, when wandering mendicants met together only during the rainy season and other regular events, before the establishment of any organization of monasteries under a rule. Hindu ashrams have followed this pattern since sometime within the first millennium BCE.

Devout admirers and disciples so often visited Christian hermits in the desert that it was difficult for hermits to maintain a thoroughly solitary life. For this reason and for purposes of survival, fourth century hermits in Egypt, Greece and the Near East found it expedient to build communities called a lavra or laura, plural lauras or laurae, of separate caves or cells, bound together by fellowship. The laura was centered upon a church, where the community met on Saturday or Sunday, and sometimes a common refectory.

Sitting between the great cosmopolitan city of Alexandria and the desert west of the Nile, the towns of Nitria, Kellia and Scetis in Egypt were popular centers of semi-hermitic monasticism in the fourth century.

This was the source of most of the wisdom of the Apophthegmata Patrum, the Sayings of the Desert Fathers. Names associated with this movement include Ammon, Macarius of Egypt, Macarius of Alexandria, Evagrius of Pontus, Arsenius the Great, and the European John Cassian.

The Desert Fathers

Macarius of Egypt is known especially for his community in Scetis, Egypt, which allowed monks to live the solitary life tempered with communal prayer, holy day ceremonies and amenities. Named after its place of origin, Scetis, this type of situation was called a “skete.”

The skete, like the laura, is considered a middle way between eremitism and coenobitism. The monastery of Saint Macarius the Great remains in operation today and the skete is an official type of order in Eastern Christianity.

Amun or Ammon, named for the Egyptian god Amun, was a desert hermit and the founder of Nitria, described by Saint Athanasius in his biography of Saint Anthony. Ammon worked with Anthony and helped organize hermits into an early monastery under his direction. By the fifth century about five thousand monks filled fifty monasteries in the area, which St. Jerome praised as “The City of God.”[1]

The Syriac-Christian Assyrian ascetic author Aphrahat (c. 280 – 345), who wrote under the Persian Empire, and the theologian and writer Ephrem the Syrian (c. 306 – 373) provide the basis of knowledge about proto-monasticism in Syria. The Syrian solitary monks, or ihidaya, plural ihidaye, were usually laity rather than clerics, with very few exceptions, vowed to celibacy, simplicity, fasting and prayer.

The Bnay Qyama, Sons of the Covenant, were ihidaye who vowed by way of covenant at baptism to celibacy and devotion. Most Syrian churches were associated with such a community of men and women (women were known as daughters of the covenant), who lived amongst the laity.

Egyptian hermits brought their customs into Jerusalem, especially all about the desert of Gaza, so that by the fifth and sixth centuries Judea was the center of the laura. This monastic system, geared toward withdrawal and martyrdom, spread and overcame other traditions in Syria and elsewhere by the fifth century.

St. Theoctistus (died 451), St. Euthymius the Great (377 – 473) and St. Sabas (439 – 532) were companions in the desert around Jerusalem, who lived at various times in caves and lauras, and were founders of monasteries.

These were the origins of the process whereby solitaries bound themselves together in fellowship and initiated cenobitic monasticism, so-called from the Greek (via Latin) words koinos and bios: the “common life.” The next articles of the Inside Monastic Culture series are devoted to the enlightening mechanisations of communal monastic life around the world.

Virgins and Philosophers

Early Proto-Monasticism

Sources

Orders and the Priesthood

- Timeline of Women Rabbis. Wikipedia, retrieved 29 Dec., 2021.

- Unearthing Menstrual Wisdom – Why We Don’t Go to the Temple, and Other Practices. Mythri Speaks, 28 May, 2015.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (Trans.). (2007). Bhikkhu Pāṭimokkha: The Bhikkhus’ Code of Discipline. Access to Insight.

- Thanissaro Bhikkhu (Trans.). (2007). Bhikkhunī Pāṭimokkha: The Bhikkhunīs’ Code of Discipline. Access to Insight.

- O’Brien, B. (2019, June 25). About Buddhist Nuns: The Tradition of Bhikkhunis. Learn Religions.

- Bekhouche, Y., et al. (2015). The Case for Gender Equality. World Economic Forum.

- Revenga, A., & Shetty, S. (2012, March). Empowering Women Is Smart Economics. International Monetary Fund, Finance & Development, 49(1).

- Andrews, R. (2017, Aug. 1). Women Are Smarter Than Men in Countries With Gender-Equal Societies. IFLScience.

- Mezzofiore, G. (2017, March 20). Stephen Hawking Says We Don’t Need Science to Prove That Women Are Equal. Mashable.

- Meng-hu. (2008). Solitude in Sufi Tradition. Hermitary.

- Davies, N. R. (2012, February). Solitude in Jewish Contemplative Practice. Jewish Contemplatives.

- Johnston, W. Monasticism. Encyclopaedia Britannica, retrieved 29 Dec. 2021.

The Solitary and the Monastery

- Clay, R. M. (1914). The Hermits and Anchorites of England. Methuen & Co., London. Digitized by Historyfish.net, August 2008.

- Book II. The People of God – Liber II. De Populo Dei. Part III. Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life. Section I: Institutes of Consecrated Life. Title I: Norms Common to All Institutes of Consecrated Life (Cann. 573–606). [Canonical reference, no direct link].

- Code of Canon Law. Vatican.va, retrieved 29 Dec., 2021.

- Eulogos. (2007). Code of Canons of the Oriental Churches. IntraText.

- Constitution and Canons. The Archives of the Episcopal Church, retrieved 29 Dec., 2021.

The Desert Fathers

- Nahas, N. (2000). The Origins and Motivations of Monasticism. Monachos.net via Wayback Machine.