A Note on the Romanization of Chinese Words

Pinyin is used in this article as the convention amongst scholars today.

With Chinese words that are relatively well known to English speakers,

the popular Wade-Giles system is initially given in parenthesis,

for the convenience of those who may be more familiar

with that system of writing Chinese words into English.

Chinese Classical Philosophy & Religion:

Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism

The story of the evolution of Chinese philosophy and world-view is both fascinating and enlightening. The subject of Chinese philosophy demands the space of entire volumes, as so many philosophers and their schools take unique views on various topics. These details are not the focus of this blog article, and will be left in their proper spheres, as we explore the more or less generally accepted developments within Chinese culture.

The written records of China, the “Middle Kingdom” of the Han people, show that the basis of Chinese culture was laid between 2700 to 2300 BCE. Mythological heroes include Youchao, “Have Nest;” Suiren, “Fire‑maker;” Paoxi the animal domesticator and discoverer of the eight trigrams; and Shennong the divine husbandman.

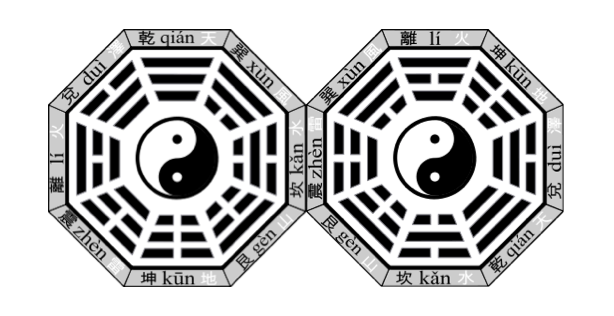

The ancient Chinese myth explains that the Goddess of Marriage Nuwa created man from a lump of clay. Her brother and husband Fuxi had the body of a serpent and the head of a man. He created the Bagua (Pa Kua), or eight trigrams, and taught them to the human race, saying that by mastering the Bagua man would gain the wisdom of the gods. The Bagua thus teaches that the universe is not the creation of gods, but of natural elements that follow constant, universal laws.

Dao is the Supreme Being, Creator and Sustainer like the now global notion of “God,” but the Dao is beyond anthropomorphism and so-called divinity. There may be the likeness of intelligent design within some aspects of the cosmos, in natural phenomenon and in what Carl Jung dubbed ‘synchronicity,’ but this is the exception rather than the rule, and there is no intelligent designer.

Chinese temples are usually a mixture of Daoist, Confucian and Buddhist religions, from the Chinese mainland to Taiwan and Hong Kong, Singapore and elsewhere in South East Asia and overseas across the globe. The Chinese maintain ancient traditions of ancestor veneration, divination, medium rituals and spiritual healing. Seasonal and other perennial festivals are held with great pomp or quiet reflection in the temple or at home. Prayers may be offered with fruit, victuals and the burning of incense to one or many deities, Buddhas, bodhisattvas and heroes, such as the goddess of mercy Guanyin or the martial god Xuanwu.

Feng shui is the art of determining the best architectural structure and interior design arrangements based on the flow of Qi (Chi), or life-force of a location. It follows the daoist cosmology and includes calculations of astrology, divination, yin-yang theory, the Wu Xing (Wu-hsing) or five elements and the Bagua, or eight trigrams. A temple or house organized by means of feng shui is always tidy and clean. It is usually designed to please the eye and assist in meditation and a good mood.

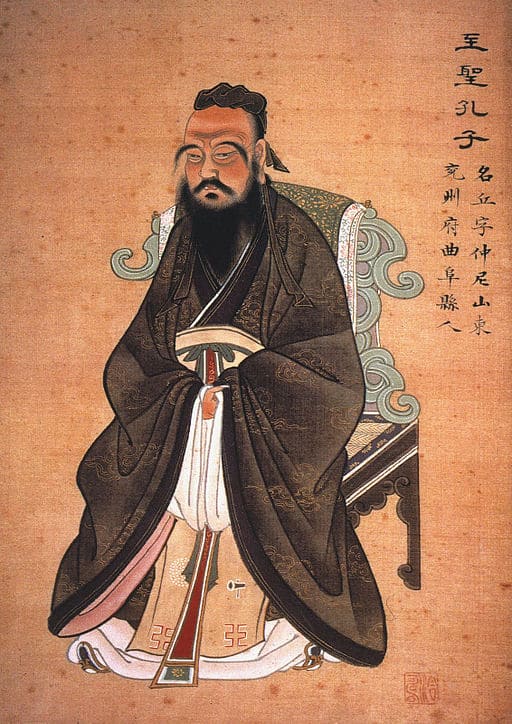

Confucius

The warlords of ancient China during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods struggled to build powerful armies and economies to attain supremacy among warring states. This competition produced a golden age where iterant philosophers were employed to advise the rulers. Laozi, Mozi, Mencius, and the Yin Yang and Five Elements philosophy belong to this era.

One of the most influential philosophers at this time was Master Kongzi (K’ung Fu-tzu), or Confucius (551 – 479 BCE), who collected the ancient Chinese Classics, the Wu Jing, or Five Classics. The Five Classics were the Book of Changes, the Classic of Poetry, the Book of History the Book of Rites and the Spring and Autumn Annals. Confucius wrote the Analects and the Great Learning. Confucius taught the cultivation of virtue and the ideal of the gentleman.

Confucius was more concerned with court etiquette than mystical attainment and even initiated a social revolution with his concept of the junzi (chun-tzu), or son of a ruler. Confucius’ junzi was the superior man due to his character rather than his pedigree. The aristocracy’s descent from divinity and their mystical ties to the spirit of their ancestors was not relevant.

Any man who followed jen, or virtue, the Will of Heaven, was a junzi. The sage-rulers Yao, Shun, and Duke Chao were perfect examples of superior men. Virtue followed the golden rule and the golden mean, basically, moderation in affairs and humanism.

The most prominent Confucian was the fourth century BCE Mengzi (Meng-tzu), whose name has been Latinized as Mencius. Mencius expanded on Confucius’ idea of virtue by asserting that man’s original nature is purely good, and he need only return to his original nature to find fulfillment. He taught that a ruler must use righteousness to govern his people, instead of force. Mencius displays a remote and impersonal kind of mysticism when he writes that the Way, as humanity, may be embodied by a man.

Confucianism

When the Imperial Academy was established in 124 BCE (during the Han period) its curriculum was entirely based on the Five Classics as collected by Confucius. Beyond the Confucian Canon, eight other classics were added to the curriculum over the next thousand years, to comprise the Thirteen Classics. These included the Analects and the Mencius, which were paired with two chapters from the Book of Rites, the Great Learning and Maintaining Perfect Balance, to become known as the Four Books.

Between the fourteenth and twentieth centuries the Four Books, replacing the Five Classics, became the core of the teachings of Neo-Confucianism and the central authoritative texts of the imperial curriculum.

When Confucius died in 479 BCE, a temple was built around his family mansion and tomb in Qufu in Shandong Province. Han Gao Zu, founder of the Han Dynasty, visited the tomb and made sacrifices to Confucius in 195 BCE. Sacrifices to Confucius were made in the Imperial University of the Han Dynasty in the third century CE. A Confucian state temple was built during the Southern Song dynasty in 454 CE. A Confucian temple was erected in Datong, the first capital of the Northern Wei Dynasty (before the capital was moved to Luoyang), in 489.

Confucian temples were constructed all over China during the Tang dynasty after it was decreed in 630 that every school must have one attached. Sacrifices were made to Confucius, his disciples and prominent Confucian scholars, as they are still, today. Although images were banned during the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1534), and meant to be replaced with spirit tablets, statues are a common feature of Confucian temples to this day. Dragons are a common theme on Chinese temples. Temple roofs are often supported by beams resting on pillars decorated with carved stone dragons.

Chinese temples are frequently comprised of many buildings and several altars at which sacrifices like oranges and other fruit are left daily. Incense is burnt in large incense burners. Priests are usually employed primarily as caretakers of the Confucian temple, and temples may serve as centers for social and charitable projects, as well as worship. As a testament to Chinese ecumenism, many Chinese temples are dedicated to the trinity of Chinese religion; Laozi, Confucius and Buddha.

Where, tradition claims, Laozi wrote the Daode jing.

The Classic of the Way and Its Virtue

A legendary figure from the fifth century BCE named Laozi (Lao Tzu) was said to be the author of a book of about 500 characters in length, in the middle of the fourth century BCE, which was called either the Laozi (“Old Master”) or the Daode jing (Tao Te Ching). Daode jing literally means “Classic of the Way (or Path) of Life and Virtue (or Power).” This Chinese classic was compiled presumably as a manual for the sage-king. It is the father of Daoism and the primary inspiration of Chinese alchemy.

The Daode jing, or The Way and Its Virtue is sometimes referred to by the name of the author to whom it is attributed, Laozi. This ancient book has had great influence over Chinese culture as a whole, including Confucianism and Buddhism. Its influence can be best seen in the prosperous and cosmopolitan former British colonies of Hong Kong and Singapore, as well as in certain locations within mainland China.

Until recently the Laozi was the second-most translated book in the history of the world after the Christian Holy Bible. The Laozi was surpassed in this position only recently by the English fiction Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone by J.K. Rowling and the total seven volumes in this series. The Harry Potter series, incidentally, is literature with an alchemical and magical theme.

Sima Qian, the Grand Historian of China in 100 BCE, wrote the official biography of Laozi, which was until recently thought to have been the true story of the author of the Daode jing. It has, however, since the 1993 discovery of the Guodian manuscripts, been shown to have originated in several sources around the late fourth century BCE. It is now thought that the Laozi is a largely a compilation of anonymous oral maxims of ancient Chinese folk wisdom.

For more information on the Laozi, Robert G. Henricks’ translations of the Guodian and Mawandi manuscripts are highly recommended.

Laozi

The notable translator Robert G. Henricks recounts a theory submitted by the Chinese scholar Guo Yi that two Laozi manuscripts existed in ancient China. The first was the book found in Guodian, mentioned by Sima Qian and supposedly written by Li Er, known posthumously as Li Dan, the Funeral Rite Teacher from Chu Jen village in Chu Province.

This was the Laozi character in the story of Confucius meeting Laozi and dubbing him the “Dragon,” probably a legend invented by Daoists, making Confucius the student of Laozi in order to elevate their Daoist philosophy and religion.[1] The second Laozi book would have been authored by the second Dan mentioned by Sima Qian, Dan the Grand Historian of Zhou, who added legalist philosophy of government material to the more metaphysical books of the earlier Li Dan.

The legend of Lao Dan, Grand Historian of Zhou, conveys that the state of Chengzhou was in chaos socially and politically. Dan, a histiographer and head of archives, understood from his knowledge of the rise and fall of kingdoms what had caused the general ruin of his country. He foresaw only further decline in the future, and so he determined to leave, heading westward.

At the western pass, known as Hangu Pass, on Mount Zhongnan in Zhouzhi County, Shaanxi Province he met Yinxi, a former aristocrat who was warden of the gate. Yinxi asked Laozi to stay and write down his philosophy for the benefit of future generations, which Laozi did, and thereupon was founded the temple complex on Mount Zhongnan.

[1] A. C. Graham, “The Origins of the Legend of Lao Tan,” Lao-Tzu and the Tao-Te-Ching

edited by Livia Kohn and Michael Lafargue, State University of New York Press, 1998, pp. 23-40.

The first two chapters of the Laozi read:

“As for the Way (Dao), the way that can be spoken of is not the constant, eternal Way.

As for names, the name that can be named is not a constant, eternal name.

The nameless is at the beginning of all things in the universe and on the earth.

Once named, it is the origin or “Mother” of these myriad things.

Constantly without desires, one realizes the mystery and perceives its subtlety.

Constantly with desires, one sees only those manifestations which one desires and seeks.

The Eternal and its manifestations together emerge from one Source.

These are two and yet they are One.

When the beautiful is known as beautiful, then other things become ugly.

When the good is known, then the bad arises.

Being and nonbeing are created together,

Difficult and easy complement each other,

Long and short define each other,

High and low distinguish each other,

Tones of distinct voices harmonize together,

Front and back follow each other.

These are all constants.

Therefore the Sage dwells in wu wei and follows the wordless teaching.”

Dao

Central to Chinese alchemy are the ideas wuji (wu chi), or nothingness, Dao (Tao) the Way, yin and yang the cosmic opposites, and the wu xing or five phases. The wu xing are often translated ‘five elements,’ but more properly phases of energy symbolized by and corresponding to the five natural elements of the material world.

Dao literally means “Way” or “Path.” The first four lines of the Laozi can be interpreted to help define, in a scientific sense, the Dao: before names exist, the Dao is the self-existent, undifferentiated One. Once things are created, differentiated and may be named, the Dao is the ultimate origin of all things.

De (Te) is power or virtue, the force or embodiment of Dao in created things. The Dao is eternal, immortal, the source and essence of being and beings, whilst all of its formations have a beginning and an end. The Way is incomprehensible and beyond description. It is what people sense when they decide to assign a name to reality, like God, or Cosmos. The Way is empty, deep and still as an abyss. It is infinite and may be used infinitely to moderate extremes and bring tranquility.

Wuji

“…emerge from one Source.” Wu is “without; not; nothing, nothingness” and ji means “ridgepole; earth’s pole; extreme limit.” Thus Wuji (Wu Chi) is literally “without ridgepole.” It appears originally in the Warring States Period Daoist classics Laozi and Zhuangzi meaning “boundless” or “without limit.” It came to imply the limitless cosmos or undifferentiated void that exists prior to Taiji (Tai Chi).

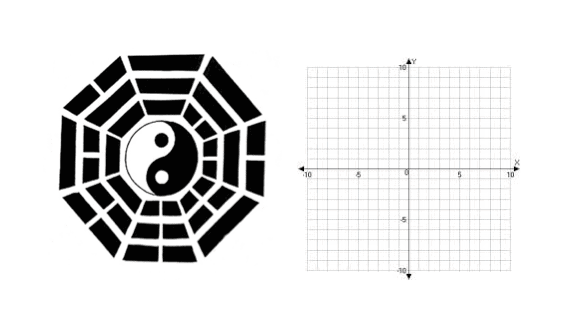

Yin and yang can represent, as the two fundamental polar elements of reality, the ones and zeros of the binary system. They may also represent the positive and negative values of Algebra, where wuji is the “origin” or zero at the center of the algebraic graph of space and time. The algebraic graph is a tool used to mathematically explain rules of existence and change within the dimensions of space and time.

The Lord Gods

The concept of a lord god that exists in the divine realm and rules the universe manifests in different ways throughout Chinese history, from ancient mythology, to monastic theology, to mystical and philosophical symbolism. Parallels can be made between four types of lord god: a primordial chaos or void, a creator and ruler god, a perfected microcosm and a hero. Often these roles overlap.

The Book of History, compiled under Emperor Shun in the 23rd century BCE (Shun’s successor was Yu, founder of the legendary Xia dynasty, the traditional first dynasty of China), lists the hierarchy of the gods under the Lord. First are the Six Venerables, Light and Darkness and the four directions between heaven above and earth below.

Next are the spirits of mountains and rivers, and deities representing the forces of nature. Finally are worthy late ancestors. The Emperor worshipped Heaven and Earth, while feudal lords worshipped Heaven and their “she”‑ their own personal territory. When a lord was conquered and replaced, his She was destroyed and replaced.

“Di,” often translated “Lord” or “God,” as representing a monotheistic god or less anthropomorphic “Supreme Being,” was the supreme deity of the Chinese people during the Shang Dynasty (second millennium BCE). The Dao comes before all things, even all deities, even the supreme deity. This negates a deity’s status as original cause and Creator. Dao also inherently implies in itself the laws of nature and the way of life for vegetable, animal and man. This precludes a role for a specific deity as author of nature’s laws or lord over man’s moral laws.

The Daoist, therefore, has no need for deities, though he may choose to adopt them according to his predilections. In China, Daoist philosophy has traditionally been mated with the wisdom of the Yijing (I Ching), or Book of Changes, Confucianism and Buddhism. As a Humanist philosophy, Laozi’s Daoism understood in its purest sense is supremely compatible with modern secular views, such as scientific skepticism.

The Opposites: Taiji

“These are two…” refers to the cosmic opposites Yin and Yang. Yin is non-being, non-existence, nothingness, nothing, void, emptiness, space, hollow, hole, vacuum, abyss, darkness, shadow, plains, negative charge, soft, earth, moon, mother, feminine, mercy, compassion. Yang is being, existence, universe, everything, fullness, things, full, force, energy, power, strength, light, mountains, positive charge, heaven, sun, father, masculine.

“…and yet they are One.” Taiji, literally “great ridgepole,” translates to “Supreme Ultimate,” the undifferentiated, absolute One or Dao, contrasted with Wuji “No Limit.” The natural Dao or Taiji is the cyclic motion of Yin and Yang, the birth and death of all things in time and space. Being arises from nonbeing, nonbeing arises from being. In this unity there is no distinct identity or isolated being.

The commonplace human being does not grasp this simultaneous unity and continuity. This insight into the nature of the universe is the mark of the enlightened. The global alchemist learns to see, understand and flow in harmony with the constantly changing manifestations of the eternal One.

The world’s major religious world-views are holistic systems of purification and cultivation of life-force. The Daoist alchemist visualizes the taiji; the “Three Treasures” or sanbao (san-pao) shen (spirit), qi (life-force) and jing (essence); the Wu Xing (five elements); the microcosmic and macrocosmic orbits; the sixty-four hexagrams; the forces of nature and ancestors; and if religious, the gods and spirits. He reads from the Yijing, the Laozi, Zhuangzi, and Doaist Canon.

The Five Phases

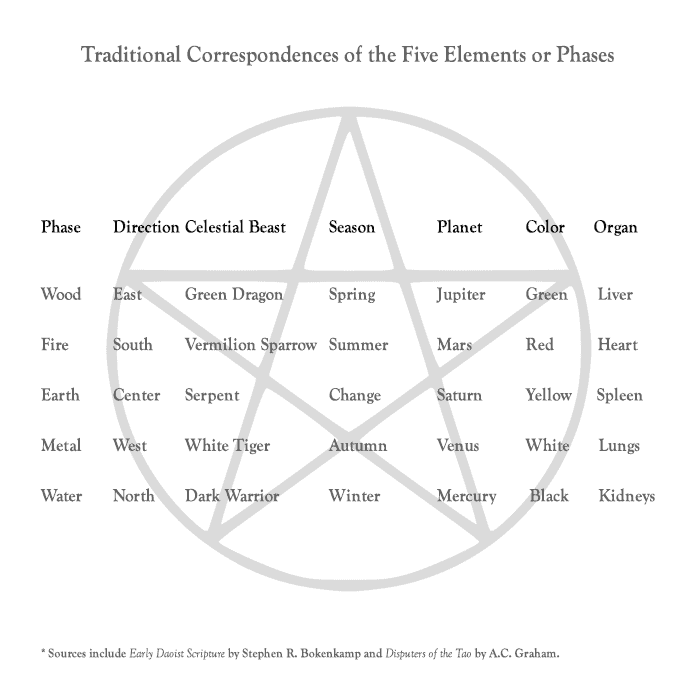

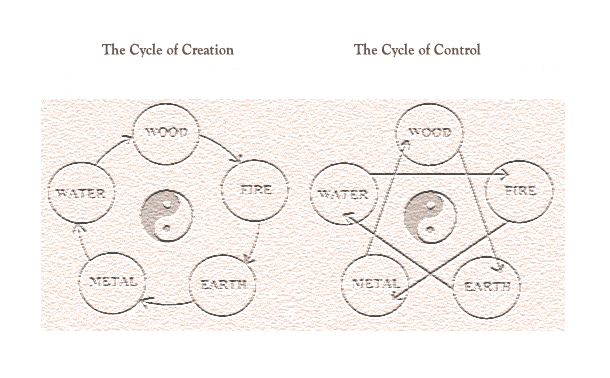

The Wu Xing or Five Phases/Five Elements doctrine was first developed by magicians of Yen and Ch’i (present Shantung, Honan and Hopei). By the third century BCE they are described in “The Great Plan” chapter of the Book of Documents or Classic of History, as Water, Fire, Wood, Metal and Soil. Correspondences were found as early as two hundred years before the Common Era, and were expanded over the centuries to include the cardinal directions (East, South, West, North, Center), the seasons of the year, the internal organs of the body, colors, tastes, tones, planets and other sets.[1]

The Theory of Creation and Control is useful as a pure idea inasmuch as it teaches the interconnectedness of all things as well as the cyclic nature of many organic structures and processes. However, the traditional Chinese methods of diagnosis and prognosis according to the relationships of constitution, organs, channels, pulses, the seasons, emotions, Qis, and “pathogenic wind” are not scientifically valid. That is, they are demonstrated to be materially false.

[1] For details see Fung Yulan, A Short History of Chinese Philosophy, The Free Press, New York, NY, 1976, pp. 131-33.

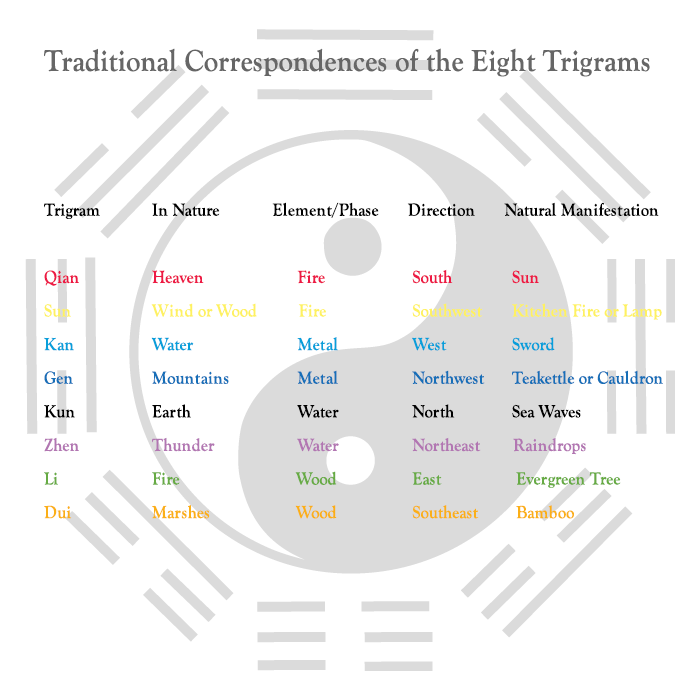

The Eight Trigrams

The ancient Chinese myth explains that the goddess Nuwa created man from a lump of clay. Her brother and husband Fuxi had the body of a serpent and the head of a man. He created the eight trigrams and taught them to the human race, saying that by mastering the Bagua, man would gain the wisdom of the gods. The Bagua thus teaches that the universe is not the creation of gods, but of natural elements that follow constant, universal laws.

Laozi’s Daoism is a natural humanistic philosophy that possesses many elements shared by the philosophies of secular humanists, who promote science as the theory and practice of discovering these underlying laws of nature.

In China ‘Wuji’, or ‘nothing’ is the origin of ‘Dao’ or the ‘One’, the ‘Law’, or the good ‘Path’ or ‘Way’ of life. Qi is the substance of the universe. Heaven is the framework. The creative spirit of Dao is qi, Heaven, or Spirit. It is called Yang, the light of the divine opposites. This good, creative energy flows in the creative ‘Pre-Heavenly Order’ symbolized by the Trigrams. The ‘Post-Heavenly Order’ of the Trigrams symbolizes Taiji, earth, yin, or the manifestation of the divine opposites.

This symmetrical cosmological arrangement represents the whole of the elements and forces of nature; the sages of China knew Heaven and Earth, the Tree of the Celestial (Heavenly) Stems and Terrestrial (Earthly) Branches. The union of these opposite forces produced a divine union – life – and man, the son of heaven.

Man had the ability to think, speak, and write. The eight trigrams were the first Chinese words. The Yijing, or Book of Changes, is the book of 64 hexagrams. The 64 hexagrams represent every possible permutation of yin and yang in terms of six lines. Each hexagram represents a possible situation and each line represents a possible condition.

The Yijing was used in the Western Zhou period (1000 – 750 BCE) as a book of divination, served as the basis for philosophical commentaries over the next several centuries, and became the oldest book in the Five Classics of the Confucian canon in the second century BCE.

The Classic of Chinese Medicine

The Chinese ancestral king was Huang‑di, the Yellow Emperor, Son of Heaven. He was the first to unify China, which he called Central Nation, by martial force. Attributed to him are the first supervisory government, the first writing system and the first calendar. The Chinese Classics mention four cardinal directions, four seasons, days, the sun and the moon, constellations and the North Star.

The Huangdi Neijing Suwen, or Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Medicine, compiled between the Warring States period (475 – 221 BCE) and the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), is universally regarded the most important book of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

It is written that Shaohao, the son of the Yellow emperor, began the first period of disorder and misfortune when people of wisdom called ‘gods’ and men were integrated. Zhuanxu, the grandson of the Yellow Emperor, separated the divine and the earthly powers by separating the flesh from the spirit.

Go to the article “Science Meets Traditional Chinese Medicine”

The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Medicine is a dialogue between the Yellow Emperor, his physician and his ministers. Early Chinese medicine is concerned with the natural manifestations of the different universal energies. These energies are described as polar energies of the ultimate origin, Dao.

Human beings and the forces of nature are described as combinations of yin and yang, the passive and active principles. Thus the tiniest human disorder is observed as an imbalance within nature, and all possible factors are examined in prognosis, from the bodily organs to the behavioral and emotional, to the weather, etc.

Thus a system of living was developed to prevent disorder. The foundation of health and strength was imagined to be the cultivation of Qi, life‑force, and the balancing and harmonizing of the polar energies of nature. Hence preventative medicine was the common practice in China and it was a physician’s disgrace to find his patient with disorder.

Obviously, many disorders cannot be prevented, but there are plenty of serious health problems that can be avoided with a healthy lifestyle. Certainly, ancient Chinese records are available for reference, but a lot of scientific research must be done in order to form a coherent holistic blueprint of preventative medicine.

Religious Daoism

The Laozi was written during the Warring States Period, when numbers of Chinese kingdoms were struggling for power, until the Ch’in gained supremacy in 221 BCE and for the first time in history united China under a single empire. The next dynasty, the Han, appeared within two decades.

The Han consolidated traditional Huang di (Yellow Emperor) yin-yang philosophy with Daoism and called it Huang – Lao. Confucianism was added to establish a world-view for Chinese culture for the next four hundred years. The spread of this culture was enhanced by a new Han invention: paper.

When the Han dynasty fell the empire gained a new priesthood and literati. Daoist organized religion first appeared with Zhang Daoling in 142 CE when he had a vision of Laozi, who told him to save the world. Zhang named himself the first Celestial Master and started the Tianshi Dao, or Way of the Celestial Masters sect. This sect was popularly known as the Way of the Five Pecks of Rice because of its initiation fee, it eventually came to persecute Buddhists and it would become an independent theocratic state in the area presently named Sichuan.

The Zhengyi sect, or Way of Orthodox Unity, arose in the Tang Dynasty, when the title of Celestial Master had lost its official status, and adopted the title of Celestial Master for the head of its own school. The sect operated a temple on Mount Longhu in Jiangxi region.

The other large sect that appeared early was the Great Peace movement, known as the Yellow Turbans for the yellow kerchiefs the members wore on their heads. This cult attempted to replace the emperor with their religious leader but their armed rebellion was put down in 184 CE.

The Eastern Jin period (317–420) and Southern dynasties period (420-589) saw the rise of the Shangqing, the School of Supreme Clarity (or Great Purity), also known as the Mao Shan sect; and Lingbao, the School of Numinous Treasure (or Sacred Jewel). In 1234 the Zhengyi sect united with the Lingbao and Shangqing schools, retaining the Zhengyi name, and in 1304 it united all Daoist sects with the exception of the Quanzhen school. It was not until the mid-Qing Dynasty (1821 – 1850) that the sect lost all formal relations with the Imperial court.

The Quanzhen sect, the Way of Completeness and Truth or Way of Complete Perfection, ascended during the Jin dynasty (1115–1234), specializing in Neidan, internal alchemy. The founder Wang Chongyang (1113- 1170 CE) was the teacher of seven disciples who founded their own lineages, including Qiu Chuji, the founder of Dragon Gate Daoism, known as the Longmen lineage, and the White Cloud Monastery in Beijing, today the seat of the Chinese Daoist Association.

Today the Zhangyi and Quanzhen sects are the only two schools of religious Daoism. Quanzhen is stricter, requiring monks to stay at a monastery, remain unmarried, to be vegetarian. The Zhangyi priests are allowed to live at home or in a monastery, marry, and eat meat. The White Cloud Monastery is the seat of the Quanzhen sect, while the Zhangyi sect is centered on Longhu Shan (Dragon-Tiger Mountain) in Jiangxi, upon which are many historic temples, including the Master’s Mansion temple complex and ancient Eastern Han Dynasty Shangqing Temple complex.

Daoism is Meditation

Following in the footsteps of the Laozi scholar Wang Bi (226 – 249 CE), the secular schools of Profound Learning and Pure Conversation studied Daoist literature analytically. Thus two types of Daoism evolved in China over the centuries, philosophical and religious, competing with the rival religious organization of Buddhism. The Daoist Canon, the Daozhang, is a collection of about 5,300 Daoist texts collected from around 400 CE to 1444 CE.

The author recommends the study of philosophical Daoism and a secular point-of-view, but it must be admitted that the religious practices offer some interesting lessons. The philosophies and meditations of the Chuang Tzu (Zhuangzi) and the Lieh Tzu (Liehzi) have inspired generations of Daoists. Although the West has known the Laozi since the late eighteenth century, it is only recently, around the turn of the millennium, that Western academics have begun to take a serious look at Daoism.

The Daode jing itself is, like other Daoist writings, a tool of meditation. It is a living teacher or guide that may initiate and lead a beginner to the Dao, guide the Daoist throughout his life, and redirect one who has gone astray back onto the Path. The lines or chapters may be read as gateways to a tranquil contemplation of the Dao that becomes mystical realization. The instructions of Laozi include not only the ways of living and leading others, but also specific methods of cultivating life- force.

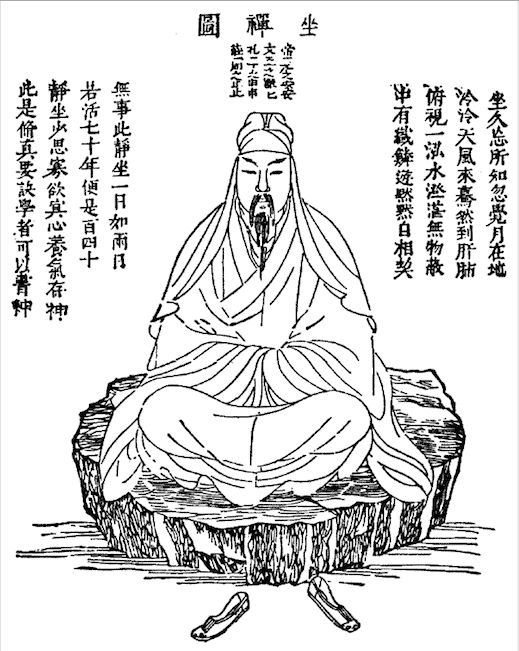

Daoist methods of cultivation include meditation, Neidan or internal alchemy (visualization and breathing exercises), Qigong (breathing and movement exercises), and Taijiquan (“Grand Ultimate Boxing”) martial arts. Wudang Daoists say that “Qigong” is the first stage of practice in Daoist internal alchemy. Qigong, which means “work with Qi,” is the art of mastering Qi or life-force and discovering the “inner medicine” to sustain heath and balance.

The lineage of religious Daoism began with the Yellow Emperor and includes Ge Hong, Celestial Master Zhang Daoling, and Chang San-Feng. Daoist religion has exoteric teachings for the people and an esoteric doctrine for its priests. Internal alchemy is to this day the central practice of the Daoist monks and their adherents all over the world. The core and apex of inner alchemy is Daoist meditation.

Types of Daoist Meditation

Daoism is the cultivation of the mind. Daoist methods of cultivation include meditation, Neidan or internal alchemy (visualization and breathing exercises), Qigong (breathing and movement exercises), and Taijiquan (“Grand Ultimate Boxing”) martial arts. Contemplation, itself, is sufficient as a means to tranquility and Oneness, but visualization, breathing and movement exercises may be used as supplementary aids, regardless their peripheral effects such as health, longevity or supernormal powers.

The three types of Daoist meditation are Guan, Ding and Cun; or insight, concentrative and visualization, respectively.[1] Guan means “to observe,” derived from Tiantai Buddhist zhiguan meditation. Zhiguan refers to the two basic stages of Buddhist meditation that form the foundation of Samadhi (enlightenment): samatha (calm) and vipassana (insight). This is the basis of what is known today as mindfulness meditation. The Chinese Daoist temple or monastery, the physical location devoted to observational meditation, is called a guan. Ding is the Daoist equivalent of Samadhi.

Cun means “to exist” or “to cause to exist,” and encompasses the visualization methods of the Daoist religious sects. Visualizations include Neiguan, “inner observation,” visualizing the processes of mind and body, including the thoughts, feelings, qi circulation and organs. Yuanyou is the “ecstatic journey” (like astral travel) that guides visualization outward to distant countries, the sun, moon and stars, to visit sacred mountains, temples, immortals and gods.

Early Daoist Meditation

The first Chinese practical instruction on meditation appeared in a poem in Seal Script on a dodecagonal jade artifact created during the Warring States Era (around 400 BCE) known as the Xingqi Jade Inscription. “Xingqi” means “Circulating Qi,” and refers to the title inscribed on the block of jade. The poem advises deep breathing to accumulate and guide life-force to rise, descend, stabilize, settle, sprout, grow and recede. This meditation is meant to align with the energies of Heaven and Earth and sustain life.

The first book to describe meditation in China was a Huang-Lao Daoist philosophical text called the Guanzi, composed during the Warring States period, about 475 – 221 BCE. Huang-Lao Daoism refers to the metaphysical and legalist philosophical tradition attributed to the mythological Yellow Emperor and Laozi. It is known as proto-Daoism because the origins of the philosophy predate the first proper Daoist text, the Laozi. Huang-Lao was the primary philosophy of the Han imperial court until it was replaced with Confucianism during the first century BCE.

The Guanzi was attributed to the seventh century BCE Prime Minister Guan Zhong. It is actually a compilation of a number of authors over several centuries, primarily philosophers at the Jixia Academy in the state of Qi (modern Shandong), later edited by the first century BCE scholar Liu Xiang. Three books in four chapters of the Guanzi describe practical instructions for meditation: The Xinshu, or “Mind Techniques” in chapters 36 and 37, Baixin, or “Purifying the Mind” in chapter 38, and the Neiye, or “Internal Work,” is chapter 49.

The fourth century BCE work titled Neiye was included as a chapter in the Guanzi in the second century BCE. The Neiye was a short manual on breath and qi meditation, now believed to be the oldest mystical text in China.[2] It was the second Chinese work to give practical instruction for meditation, following only the Xingqi Jade Inscription. It introduced to traditional Chinese medicine and Daoist internal alchemy (Neidan) the concept of the Three Treasures: essence (jing), life-force (qi) and spirit (shen), and influenced the Laozi and the Zhuangzi.

Meditation in the Laozi

Meditation in the Laozi is implied along with a lifestyle of cultivation of a meditative state of mind. The closest the Laozi comes to practical instruction on meditation is in the tenth chapter, which describes soft breathing, a calm mind, lucidity and a prudent laissez-faire attitude:

Visualizing the mortal soul[3] and embracing the One,

Can you be undivided?

Concentrating your qi[4] to become soft,

Can you become like a newborn infant?

Purifying and making clear your profound mirror[5],

Can you leave no blemish?

Loving people and cultivating the state,

Can you do it with wu-wei?[6]

Opening and closing the gates of Heaven[7],

Can you play the part of the Feminine Principle?[8]

Comprehending all within the Four Directions,

Can you do it with wu-wei?

Produce and nourish.

Produce, but do not try to possess;

Work, but do not depend on the reward;

Support, but do not control;

This is called profound virtue.[9]

Chapter Sixteen of the Laozi describes a perception of eternal void and a meditative calm, which is a practical instruction for Daoist meditation: “Emptiness- the utmost limit: Tranquility- the center.” It is notable that in the early Chinese meditative tradition there is no instruction for posture, as there is in ancient Indian tradition. The Daoist meditation could be practiced lying down, sitting, standing, walking, and in fact, during every activity, which seems to be the goal.

Neo-Confucian Meditation

The fourth century BCE philosopher Mencius, the primary disciple of Confucius, was concerned with the development of a person’s xin, or heart-mind, for physical, mental, moral and spiritual purposes. His system involved the Confucian way of life that included exercises to cultivate qi (life-force). Nourishing qi meant right behavior (yi) in alignment with the Dao (2A2 & 6A7-8).[10]

Neo-Confucianism developed its own style of meditation in the Song dynasty. Jing Zuo means “quiet sitting” or “sitting in silence” for health or spiritual cultivation. Zhu Xi (1130 – 1200) represented the Rational School. He promoted the investigation of the world as a complementary practice to contemplation of thoughts and actions during silent sitting meditation to achieve enlightenment.

Wang Yangming (1472 – 1529) represented the Idealistic School when he rejected investigation of worldly matters during silent sitting meditation, encouraging instead self-examination with intent to grow as a moral person. Qigong may also be practiced during jingzou.

Zhuangzi’s Meditation

The fourth – third century BCE Zhuangzi is the first Chinese text to specifically suggest sitting meditation. It describes xinzhai, “heart-mind fasting,” (Ch. 4) and zuowang, “sitting forgetting,” (Ch. 6) in the context of a dialogue between Confucius and his favorite disciple Yan Hui.

From Chapter 4:

Yen Hui: “May I ask what the fasting of the mind is?”

Confucius said, “Make your will one! Don’t listen with your ears, listen with your mind. No, don’t listen with your mind, but listen with your spirit. Listening stops with the ears, the mind stops with recognition, but spirit is empty- and waits on all things. The Way gathers in emptiness alone. Emptiness is the fasting of the mind.”[11]

From Chapter 6:

Yen Hui said, “I’m improving!”

Confucius said, “What do you mean by that?”

“I’ve forgotten benevolence and righteousness!”

“That’s good. But you still haven’t got it.”

Another day, the two met again and Yen Hui said, “I’m improving!”

“What do you mean by that?”

“I’ve forgotten rites and music!”

“That’s good. But you still haven’t got it.”

Another day, the two met again and Yen Hui said, “I’m improving! ”

“What do you mean by that?”

“I can sit down and forget everything!”

Confucius looked very startled and said, “What do you mean, sit down and forget everything.'”

Yen Hui said, “I smash up my limbs and body, drive out perception and intellect, cast off form, do away with understanding, and make myself identical with the Great Thoroughfare. This is what I mean by sitting down and forgetting everything.”

Confucius said, “If you’re identical with it, you must have no more likes! If you’ve been transformed, you must have no more constancy! So you really are a worthy man after all! With your permission, I’d like to become your follower.”[12]

Zhuangzi On Qigong

In Chapter 15 the Zhuangzi describes qigong exercises and discards them as the way of the scholar, not the way of the sage, for the way of the sage is in silence, rest and ease:

“To pant, to puff, to hail, to sip, to spit out the old breath and draw in the new, practicing bear-hangings and bird-stretchings, longevity his only concern – such is the life favored by the scholar who practices Induction, the man who nourishes his body, who hopes to live to be as old as P’eng-tsu.

“But to attain loftiness without constraining the will; to achieve moral training without benevolence and righteousness, good order without accomplishments and fame, leisure without rivers and seas, long life without Induction; to lose everything and yet possess everything, at ease in the illimitable, where all good things come to attend – this is the Way of Heaven and earth, the Virtue of the sage.

So it is said, Limpidity, silence, emptiness, inaction – these are the level of Heaven and earth, the substance of the Way and its Virtue. So it is said, The sage rests; with rest comes peaceful ease, with peaceful ease comes limpidity, and where there is ease and limpidity, care and worry cannot get at him, noxious airs cannot assault him. Therefore his Virtue is complete and his spirit unimpaired.”[13]

Meditations of Legendary Daoist Masters

The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Medicine (the Neijing Suwen), written about 240 B.C.E., mentions ancient “immortals” who used proper nutrition, breathing and stretching exercises and meditation to become healthy, long-lived and super-human.

Go to “Science Meets Traditional Chinese Medicine”

The 139 BCE Huainanzi, an encyclopaedic collection of essays derived from debates surrounding the perfect state held at the court of Liu An, King of Huainan, describes meditation methods as “techniques of the mind.” Breath control is the physical method of meditation, but is secondary to the mental discipline. The Huainanzi promotes genuineness and subtlety. It claims that cultivating life-force and spirit are essential to “mounting the clouds,” and “penetrating Heaven,” references to Daoist immortality.

The two earliest and most important commentaries to the Laozi, after the Xiang’er, are the Wang Bi and Heshang Gong. The former is the inspiration and standard commentary for secular Daoists, or Daojia; the latter is a dominant staple of religious Daoists. Wang Bi was a scholar who produced a famous commentary on the Yijing (I Ching), as well as his commentary on the Laozi. Wang Bi’s method of interpretation was to view words and images as tools of understanding, to know the meaning beyond the forms, Dao being the formless One.

The legendary Han Daoist hermit, Heshang Gong, “Riverside Elder,” was probably not a historical figure, but a legend that developed with the rise of internal alchemy and the Daoist religion. The commentary ascribed to this figure was a guide to meditation involving the cultivation of the Three Treasures, jing (essence), qi (life-force) and shen (spirit), with the aim of Daoist immortality.[14]

Chinese alchemy preserved and expanded upon Daoist meditation so much so that it became a religion. Even as it was later mostly superseded by Buddhism and then Communist ideology, the Daoist religion has helped define China even to the present day. Chinese alchemy has had a profound influence even in the West, from Arab proto-scientists and European Renaissance alchemists to the psychotherapy of modern medical science.